T. J. Tallie, “On Zulu King Cetshwayo kaMpande’s Visit to London, August 1882”

In August of 1882, the deposed Zulu monarch Cetshwayo kaMpande arrived in London to plead for the restoration of his kingdom, from which he had been deposed following the Anglo-Zulu War of 1879. Despite the ferocity of the war, particularly after Britain’s humiliating defeat at the Battle of Isandhlwana in January 1879, the newly elected Gladstone government sought to repudiate larger imperial goals and reversed their decision, approving Cetshwayo’s restoration. This article focuses on the depictions of Cetshwayo in the metropolitan press during his momentous 1882 visit.

Isaac Land, “On the Foundings of Sierra Leone, 1787-1808”

This article offers a critical reading of who was sent to Sierra Leone, why West Africa was chosen as the destination, and discusses the larger meanings, contexts, and legacies of the “Province of Freedom.”

Timothy Johns, “The 1820 Settlement Scheme to South Africa”

The 1820 settlement scheme to South Africa marks an important conjuncture both for the colony’s internal development and for the rhetoric of immigration in the internal politics of Britain. Examining the rationale for the venture in light of the seminal historical event of the age—the Peterloo Massacre of 16 August 1819—and in light of Romantic notions of the “Noble Savage,” this entry attempts to demonstrate how concerns surrounding the South African scheme came to be entangled within larger debates over joblessness, slavery, class struggle, and inanition in early nineteenth-century British culture. Limiting its focus to a reading of The Emigrant’s Cabin (1822, 1834), a poem by the settler-poet Thomas Pringle (1789-1834), the entry argues that 1820 settler rhetoric navigated debates over labor through a novel engagement with time. By imagining a two-tiered system of labor time in the poem—one for settlers, based on unemployment relief and freedom from the oppressive pace of industrial life; and one for the African labor force on the eastern Cape farms, based on missionary discipline, a proto-Victorian program of “improvement,” and freedom from slavery—Pringle’s verse helped foster a British cultural identity in the Cape that resonates even today.

Anne Clendinning, “On The British Empire Exhibition, 1924-25”

The British Empire Exhibition, held in 1924 and 1925, assembled the member nations of the empire to develop imperial trade connections and to cultivate closer political ties between Britain and her territories. A commercial, educational and imperial spectacle, the exhibition reminded Britons of the material and political value of the empire, as the nation struggled to recover from the economic impact of the Great War. For some colonial participants, however, the British Empire Exhibition enabled them to present a distinct national identity in pursuit of greater autonomy from Britain, while for others, it provided a forum in which to critique racial discrimination within the empire.

Sharon Aronofsky Weltman, “1847: Sweeney Todd and Abolition”

The prolific (but rarely remembered) Victorian playwright George Dibdin Pitt wrote the first Sweeney Todd dramatization in 1847 for the Britannia in London’s East End, tailoring his melodrama for the theater’s particular audience and the acting company’s individual talents. Not published until 1883 in Dick’s Standard Plays (as Sweeney Todd: The Barber of Fleet Street, or The String of Pearls), the printed play differs significantly from Dibdin Pitt’s original, which was initially performed on 1 March 1847 as The String of Pearls, or The Fiend of Fleet Street. Scholars who rely on the 1883 Sweeney Todd to discuss the 1847 melodrama are in many respects talking about a different play. One major difference involves a main character who appears only in the 1847 version. In the 1846-47 novel, a faithful dog named Hector is important to the plot; in the 1847 play, he is transformed into a major heroic character who foils the play’s villains — no longer a dog, but a deaf-mute black boy, a former slave from British Honduras who loyally continues to serve his former owner and current employer out of love and gratitude for his freedom. By including this character, Dibdin Pitt takes an identifiably abolitionist stance, working through what was still England’s strong sense of moral achievement in abolishing slavery and still strong sense of purpose in working to end slavery in the United States. But by 1883, in regards to race and colonialism, the cultural work of Dibdin Pitt’s play without Hector operates through an unthinking backdrop of the Empire’s power and the status quo of racial hierarchy.

Jo Briggs, “The Second Boer War, 1899-1902: Anti-Imperialism and European Visual Culture”

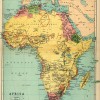

The Second Boer War, part of the “Scramble for Africa” among European powers, was fought from 1899 and 1902 in what is now South Africa between British Imperial forces and the Transvaal Republic and Orange Free State. The war occurred during the period of so-called New Imperialism (ca. 1880 to 1914) characterized by rising nationalism, racism, Social Darwinism, and genocidal thinking. Occurring roughly in the middle of this period, the Second Boer War became the focal point for a variety of hopes, anxieties, politics, and ideologies. An examination of periodicals created specifically to protest against the war shows that the conflict resonated within diverse local contexts, revealing the complex interplay between global events and local politics.

Dane Kennedy, “The Search for the Nile”

This essay examines the social and cultural contexts that informed British explorers’ efforts to discover the source of the Nile. It highlights the relationship of these expeditions to existing systems of trade and power in East Africa, British imperial interests in the region, and the development of a celebrity culture in Britain.

Matthew Rubery, “On Henry Morton Stanley’s Search for Dr. Livingstone, 1871-72”

The meeting between Henry Morton Stanley and Dr. David Livingstone in Africa was one of the most sensational news stories of the nineteenth century. Stanley’s greeting, “Dr. Livingstone, I presume?” is still a well known phrase. The Scottish missionary had been out of contact for several years when an American newspaper sent its correspondent to search for him. The meeting turned public attention to the African slave trade and was a pivotal moment in the relationship among the United States, Europe, and Africa.