Abstract

In August of 1882, the deposed Zulu monarch Cetshwayo kaMpande arrived in London to plead for the restoration of his kingdom, from which he had been deposed following the Anglo-Zulu War of 1879. Despite the ferocity of the war, particularly after Britain’s humiliating defeat at the Battle of Isandhlwana in January 1879, the newly elected Gladstone government sought to repudiate larger imperial goals and reversed their decision, approving Cetshwayo’s restoration. This article focuses on the depictions of Cetshwayo in the metropolitan press during his momentous 1882 visit.

The outbreak of the Anglo-Zulu War thrust the ![]() Zulu people and their king, Cetshwayo kaMpande, to the forefront of British public attention, particularly after the disastrous defeat of imperial troops at

Zulu people and their king, Cetshwayo kaMpande, to the forefront of British public attention, particularly after the disastrous defeat of imperial troops at ![]() Isandhlwana in January of 1879.[1] Metropolitan familiarity with Cetshwayo and the Zulu people did not begin with the Anglo-Zulu War, however. Audiences had encountered demonstrations of African and ostensibly ‘Zulu’ performers in London since at least the 1850s, and travel reports from the British colony of Natal in southeast Africa had described consistently the martial valor of Zulu men who lived in the kingdom directly beyond its borders. Yet the news of Isandhlwana represented a significant increase in metropolitan press coverage of the peoples of the Zulu kingdom. In particular, discussions of Cetshwayo’s ‘barbarous’ nature and the militant chaos of the Zulu kingdom filled press pages throughout the spring and summer of 1879. However, with the arrival of Sir Garnet Wolseley in August and the end of hostilities following the capture of

Isandhlwana in January of 1879.[1] Metropolitan familiarity with Cetshwayo and the Zulu people did not begin with the Anglo-Zulu War, however. Audiences had encountered demonstrations of African and ostensibly ‘Zulu’ performers in London since at least the 1850s, and travel reports from the British colony of Natal in southeast Africa had described consistently the martial valor of Zulu men who lived in the kingdom directly beyond its borders. Yet the news of Isandhlwana represented a significant increase in metropolitan press coverage of the peoples of the Zulu kingdom. In particular, discussions of Cetshwayo’s ‘barbarous’ nature and the militant chaos of the Zulu kingdom filled press pages throughout the spring and summer of 1879. However, with the arrival of Sir Garnet Wolseley in August and the end of hostilities following the capture of ![]() Ulundi in July of 1879, British press depictions of Cetshwayo began to shift. No longer was he described predominantly as a destructive and capricious despot. Rather, periodical press pages returned to their previously admiring descriptions of Zulu military power after the war’s conclusion. Following his capture in September 1879 and exile in the

Ulundi in July of 1879, British press depictions of Cetshwayo began to shift. No longer was he described predominantly as a destructive and capricious despot. Rather, periodical press pages returned to their previously admiring descriptions of Zulu military power after the war’s conclusion. Following his capture in September 1879 and exile in the ![]() Cape Colony, Cetshwayo became a source of continuous debate about the limits of both colonial settlement and imperial hegemony.

Cape Colony, Cetshwayo became a source of continuous debate about the limits of both colonial settlement and imperial hegemony.

The two years following Cetshwayo’s capture emphasized instead the royal dignity of the captive as press writers debated the very legitimacy of the British invasion, often to the white-hot fury of settler observers in the adjacent southern African colony of Natal. The frequently prescient satirical periodical Funny Folks described the rapid shift in press coverage following Ulundi in a note just a month after the end of the war:

The danger is that we shall wind up the farce by a ridiculous display of hero-worship on Cetywayo’s account. Already the Turncoat press discovers that Cetywayo was ‘every inch a king,’ but ‘never showed so royal as when the other day he stepped out from his hiding—place’ –he did, in effect, crawl out of his kraal—‘and, with a proud demeanour that struck his pursuers with admiration and melted them to sympathy, surrendered himself a prisoner. The Zulu nation recovered by that one supreme effort of their fallen King much of the dignity which had once pertained to them as the noblest native race of Africa, Royal to the last, and at the last more royal than ever,’ &c, &c.(“The Triumph of Cetywayo” 316)

Following the close of the war, Cetshwayo ceased to be the threatening barbarian that stood ready to despoil Natal (at least to metropolitan eyes—for the majority of settlers in Natal, Cetshwayo represented ever-present threats of colonial ruin for the rest of his life). Rather, a new period of myth-making began in which Cetshwayo’s noble status and royal authority would be privileged, now that he was no longer perceived by many to present a military threat to British interests in ![]() southern Africa. This new, pro-Cetshwayo argument would instead advocate for the restoration of the monarch, offering a vision of colonialism in Natal and the British Empire more widely that rested upon notions of justice, fair play, and hierarchical order. This, of course, would be utterly inimical to the coalition of settlers, colonial officials, and other interested parties that were invested in the Ulundi Settlement struck by Wolseley in 1879. For administrators like Wolseley, a restoration of Cetshwayo would undo Wolseley’s grandiose designs for peace in the colony. For many settlers, Cetshwayo’s return would reignite a threat to their sovereignty and serve as a rallying point for indigenous disaffection. Arguing that “the interests of peace and order in South Africa would be seriously imperiled,” Natal’s legislators voted to pass a formal protest at the idea of Cetshwayo’s Return every year from 1880 to 1883 (Natal [Colony], Debates of the Legislative Council, 1880 Pt. 2 184). Although their interests were not uniform, each of these groups shared a profound attachment to the idea of Cetshwayo’s continued exile; the restoration of the monarch would spell the undoing of their tenuous plans for Natal and Zululand. As a consequence, groups both in favor of and opposed to Cetshwayo’s return began planned attacks in the metropolitan press, intent on demonstrating either the security of the region in a post-Cetshwayo era or the failure of the Empire to uphold its claims to justice. These depictions would be more starkly drawn as Cetshwayo was finally granted his audience to visit London in August of 1882.

southern Africa. This new, pro-Cetshwayo argument would instead advocate for the restoration of the monarch, offering a vision of colonialism in Natal and the British Empire more widely that rested upon notions of justice, fair play, and hierarchical order. This, of course, would be utterly inimical to the coalition of settlers, colonial officials, and other interested parties that were invested in the Ulundi Settlement struck by Wolseley in 1879. For administrators like Wolseley, a restoration of Cetshwayo would undo Wolseley’s grandiose designs for peace in the colony. For many settlers, Cetshwayo’s return would reignite a threat to their sovereignty and serve as a rallying point for indigenous disaffection. Arguing that “the interests of peace and order in South Africa would be seriously imperiled,” Natal’s legislators voted to pass a formal protest at the idea of Cetshwayo’s Return every year from 1880 to 1883 (Natal [Colony], Debates of the Legislative Council, 1880 Pt. 2 184). Although their interests were not uniform, each of these groups shared a profound attachment to the idea of Cetshwayo’s continued exile; the restoration of the monarch would spell the undoing of their tenuous plans for Natal and Zululand. As a consequence, groups both in favor of and opposed to Cetshwayo’s return began planned attacks in the metropolitan press, intent on demonstrating either the security of the region in a post-Cetshwayo era or the failure of the Empire to uphold its claims to justice. These depictions would be more starkly drawn as Cetshwayo was finally granted his audience to visit London in August of 1882.

This article focuses on the momentous August 1882 visit of Cetshwayo kaMpande (r. 1873-79, 1883-84), the king of the independent Zulu nation until his deposition and exile by the British following the Anglo-Zulu War of 1879, and depictions of the monarch’s visit in the British metropolitan press. These depictions used larger discourses of race and gender, particularly in discussing the fate of the British colony of Natal after the Anglo-Zulu War of 1879. These discourses, which circulated between the metropole and the colony, in turn shaped the political landscape in both places, and led to significant changes for settlers and indigenous peoples alike. Metropolitan writers paid particular attention to Cetshwayo’s displays of dignity, composure, and bearing, which subverted the idea of rational, reasoned rule being the sole preserve of the white settler men who hoped to rule Natal. Cetshwayo’s deliberately scripted appearances in London as well as his sympathetic spokespeople across the empire played into pre-existing ideas of class and royal hierarchy to press the deposed monarch’s claim to the throne.

When Cetshwayo kaMpande first set foot in London in August 1882, he stepped into broader discussions about empire, race, and masculinity. The king’s visit—and the simultaneous discussions of the occasion—catalyzed already ongoing conversations about the future of imperial rule, the conditions of settler government, and hierarchies of race and gender. While Cetshwayo and his supporters worked through the larger circulations of print media to return the king to power, and settlers on the ground worked to thwart this result, the stakes for Cetshwayo and his visit were about more than a restored kingdom. Rather, the circulations of Cetshwayo kaMpande—both in print and in person—between the metropole, Natal, and Zululand reveal that the failures of colonial hegemony did not occur simply in local colonial space but, rather, through the implementation of print technology, across discursive networks, and in the very heart of the empire itself.

Reading Empire: Natal, Print, and the Question of Sovereignty

As a prevailing and increasingly accessible technology of information, newspapers and periodicals in late nineteenth-century Britain provide an invaluable window into the multilayered realities of imperial rule and colonial thought. Large numbers of people in the late nineteenth-century metropole read popular texts, and the depictions within them subsequently spread considerably, creating a powerful discursive web that responded to current events and shaped national reactions to them—both on a personal and a political level. For centuries, newspapers and periodicals had offered a variety of information to a privileged readership in the British Isles, but access was not readily available for a significant percentage of the population prior to the nineteenth century. The broadening of the franchise in 1832 coincided with the gradual decreasing of taxes and subsidies on print and periodicals. By 1861, newspaper taxes and paper duties had finally been removed, and the costs of printed material plummeted within Britain (Altick). By all accounts, the circulation of materials throughout the latter half of the nineteenth century is impressive, and indicative of a growing reading public. Most major London newspapers could claim anywhere between 50,000 and 200,000 readers in regular circulation by the 1870s, and other industrial centers like ![]() Manchester could boast at least a quarter million readers in regular circulation (Altick 355–56).[2]

Manchester could boast at least a quarter million readers in regular circulation (Altick 355–56).[2]

The nineteenth-century periodical in Britain provides a particularly useful opportunity for understanding how everyday Britons saw the empire that surrounded them. While it is difficult to determine exactly how the individual British reader interpreted the news that appeared before him or her in the metropole, it is possible to observe broad trends in the information disseminated in the imperial press that these men and women would have read. As much of the awkwardly named ‘New Imperial History’ has sought to assert, nineteenth-century Britain cannot be bifurcated into the easy dialectic of ‘domestic/local’ and ‘foreign/imperial’; the constant movement of bodies from the Isles to and from the corners of the globe meant that such a division was imagined at best. Newspapers and periodicals were where that very imagining occurred. Certainly the central preoccupation of ‘Englishness,’ the ostensible conservative core of the imperial project that conveniently elided ![]() Ireland,

Ireland, ![]() Wales,

Wales, ![]() Scotland (and indeed much of England outside of the southeast) reinforces the fact that sub-national identity was constantly made and remade through recourse to empire (Fraser, Green, and Johnston 128; Kumar). Indeed, as countless British periodical references throughout the century can attest, empire was everywhere, but the empire became a site of intense argument, contention, and debate throughout the latter half of the century.[3]

Scotland (and indeed much of England outside of the southeast) reinforces the fact that sub-national identity was constantly made and remade through recourse to empire (Fraser, Green, and Johnston 128; Kumar). Indeed, as countless British periodical references throughout the century can attest, empire was everywhere, but the empire became a site of intense argument, contention, and debate throughout the latter half of the century.[3]

Monarch in the Big City: Metropolitan Descriptions of Cetshwayo in London

Despite the fervent protests of Natal’s legislature, and the grave pronouncements of other officials, Cetshwayo was formally granted permission to visit London in 1882. He arrived on Thursday, 3 August 1882, and was accompanied by a flotilla of British reporters, eager to spread information on the Zulu monarch to a metropolitan readership. Papers dutifully reported that Cetshwayo had travelled with servants, a doctor, and an interpreter, noting that no women accompanied him.[4] The Illustrated London News described the king as “a fine burly man, with a pleasant good-humoured face, though almost black; his manners are frank and jovial, but still dignified, and he wears a European dress” (“Cetewayo in England”). Immediately after disembarking, Cetshwayo was treated to a circle of cheers from admiring visitors, who wished to welcome the potentate to the metropole. The newspapers also reported on particular exchanges that Cetshwayo had with his fellow travelers upon leaving:

A clergyman, holding out his hand, said very heartily, ‘Goodbye, King.’

‘Goodbye,’ responded Cetywayo, in excellent English; then turning to one of his companions, he said, in his own language, ‘He is going home now he has come to his own people and is going to leave us.’ (“The Arrival of Cetywayo”)

Despite the mild condescension in praising his use of the word “good-bye” as an excellent command of the English language, the press coverage of Cetshwayo’s landing is significant in that it portrays the king as both an arriving dignitary and a celebrity that fascinated the metropole.

The initial news coverage of Cetshwayo’s visit specifically worked to play up the monarch’s ‘civilized’ and fitting royal behavior, directly refuting the press depictions of the previous years, which emphasized his barbarism:

In his demeanour Cetywayo is most gentle, utterly belying the popular conception which pictures him as a rude and turbulent savage. His intelligence is shown by the questions which he addresses to his interpreters, and his capacity to win men’s friendship by the extraordinary sympathy felt with him by the passengers of the Arab. He has been, in fact, everyone’s friend, and the passengers who left the ship at

Plymouth bade him a hearty farewell. (“The Arrival of Cetywayo”)

Cetshwayo was thus rendered as a gracious and friendly king, whose royal demeanor challenged the legitimacy of the British conquest of his kingdom. The initial press coverage of Cetshwayo’s trip served to advocate for hierarchical modes of respect for a powerful male leader, in turn reflecting a British self-imagining as an orderly, moral, and highly structured society. Thus, to depict Cetshwayo positively as a gracious, engaging, friendly monarch offered a conception of British imperialism that demanded a self-representation as a just and respectable society.

Cetshwayo was certainly aware of the power of the press and its ability to shape imperial discourse. Reports on his visit reveal that the king focused on particular questions that were likely to enhance his cause in the metropole, and demonstrated an astute knowledge of his coverage in the metropolitan press (Anderson 310). Multiple papers reported that Cetshwayo considered himself “much aggrieved at the descriptions given of him in the newspapers, ‘as if he were a dog.’” Recognizing the importance of the press to both hinder his cause as well as to amplify his own position on southern African politics, Cetshwayo “declared in emphatic tones that there never ought to have been any war, and ascribes the conflict to ‘the little grey-headed man’ (Sir Bartle Frere) and the newspapers, against the majority of which he is deeply prejudiced. His people he says, want him” (“The Arrival of Cetywayo”). While Cetshwayo demonstrated an understanding of the press as a means of pursuing his own claims to restored sovereignty, he did not manage to sway all reporters. In the same issue of the Leeds Mercury that lauded Cetshwayo’s arrival, another reporter sniffed at the entire affair, writing:

Cetywayo has duly reached England, and already we hear that the usual deplorable but seemingly inevitable lionising has begun. . . the ex-King was besieged by the notoriety hunters of the town. . . . It would be well if ‘the little grey-headed man,’ as Cetywayo designates Sir Bartle Frere, were to make the public of England acquainted with some facts regarding the life and habits of the King when he was supreme in Zululand with which the students of the South African Blue Books are familiar, but of which it is to be hoped the female admirers of the gentle monarch are ignorant. (“Politics and Society”)

The dissenting report on Cetshwayo viewed the king’s arrival as an ultimate propagandic performance, and an unconvincing one at that. Further, the author sought to subvert the ennobled male power of Cetshwayo in the press by hinting both that the king’s polygamous marriages and his warlike actions (subjects unfit for ‘proper’ Victorian women to read) would undermine the growing support for the monarch among both men and women. While Cetshwayo could and did court public opinion in pursuit of his cause, not all reporters were convinced by his display.

Despite the presence of detractors, however, Cetshwayo’s visit had the intended effect upon the public imagination and government ministers. As the king toured the major centers of British power in London, citizens took to the newspapers on his behalf (Parsons 115–119). Colonel Samuel Dewe White, veteran of British campaigns in ![]() India, wrote to British papers in August of 1882, reflecting on Cetshwayo’s mission:

India, wrote to British papers in August of 1882, reflecting on Cetshwayo’s mission:

Sir,–The presence of Cetywayo in England is calculated not only to excite pity for fallen greatness, but to arouse the conscience of the nation in regard to our dealings with his sable Majesty, whose prolonged captivity cannot be justified either religiously or morally. Sir W. Erle, an earnest patriot in Charles I.’s third parliament, once said that ‘The cause of justice was God’s cause.’ It is of importance, therefore, to know what justice requires us to do in this matter. Let us place our hands upon our hearts, with the sincere desire to ascertain this. Imprimis, it should be considered that Cetywayo, whether he be regarded as a noble savage or a barbarous ruler, at all events fought bravely for the independence of his country against British aggressors, and being eventually conquered, he was unfairly treated in being deprived of those usages of war practised amongst civilised nations, which he was entitled to, because the colour of Cetywayo’s skin and his African birth ought not to prejudice his claim to be thus dealt with. In point of fact, the waging war with the Zulus, partitioning their country, and keeping their King as a prisoner of war are three wrong things we have done. Therefore, prompt reparation ought to be made to Cetywayo by restoring him to his longing subjects, and then doubtless he will enjoy his own again. (White, S. Dewe)

In White’s estimation, Cetshwayo’s civilizational status was irrelevant; whether he be seen as ‘noble’ or ‘barbarous,’ the fact remained that he and his male warriors acquitted themselves bravely on the field of battle, and in so doing, deserved recognition and respect by a British government. In the letter, Cetshwayo became something of a cipher for the larger question of the justice of British imperial rule; if the king continues to be held, against morals and proper custom, the question of British justice, and the rhetorical underpinnings of colonial domination become visible. For men like White, Cetshwayo’s visit, therefore, offered a prime opportunity for righting colonial arrogance and, in so doing, offering a reform of the British system.

As a result, Cetshwayo presented a challenge to the nature of imperial rule, but one that could easily be resolved, particularly in light of more pressing global matters:

Moreover, sound policy also requires the conciliation of the Zulus by the restoration of their King, because our hands just now are quite full with the affairs of Ireland and the Egyptian imbroglio, which makes it necessary that we should steer quite clear of another African war. Lastly it would be wise at once to concede to the claims of justice what otherwise might be ungraciously extorted under a pressure which it would be highly inconvenient to attempt to resist. (White, S. Dewe)

For White, Cetshwayo’s restoration provided both a needed rhetorical salve to the idea of British justice and a practical consideration for pragmatic imperialists. Recognizing the moral claim of Cetshwayo, White urged British accommodation, lest continued instability lead to yet another imperial war in South Africa, something a government stretched thin by engagements in ![]() Egypt and Ireland could not possibly consider. Ultimately, White’s observation of Cetshwayo’s voyage served to encourage British justice while eyeing the inevitable military costs to maintaining hegemony in Natal and Zululand if such a plan were not adopted.

Egypt and Ireland could not possibly consider. Ultimately, White’s observation of Cetshwayo’s voyage served to encourage British justice while eyeing the inevitable military costs to maintaining hegemony in Natal and Zululand if such a plan were not adopted.

The British press meticulously reported upon the movements of the king during his month long visit to London. An eager public could read their fill on his attire, his ‘kingly dignity,’ and the vicissitudes of his appearance. At every stop, from meeting Parliament to viewing naval installations, Cetshwayo found himself quizzed as to his thoughts on the House of Commons, the royal family, English military might, and a myriad of other aspects of metropolitan life. His responses were frequently circumspect, limited not only through the difficulties of translation but also as a result of attempting to project a kingly dignity while simultaneously attempting to convince an ostensibly magnanimous imperial government to restore his position. The Saturday Review gently mocked these earnest but empty interviews in their assessment of Cetshwayo’s visit, highlighting his description of Prime Minister William Gladstone as “a grand, kind gentleman” and his astute avoidance of representatives of the temperance movement, who sought to obtain a recorded statement that Cetshwayo was firmly against the idea of indigenous drinking (“Cetewayo at the Stake”).

While journalists freely wrote of Cetshwayo as a native king overawed by the ostensible technological and social wonders of London, these observations also carried within them profound criticisms of the empire. Describing Cetshwayo’s touring of military installations, colonial institutions and other structures of power, a London paper described the king as “An African Caractacus,” paraphrasing the legendary Celt’s observations of ![]() Rome after his capture: “How is it possible that a people possessed of so much magnificence could begrudge me my humble kraal in Zululand?” (“Comic Papers”). Caractacus, like the Iceni queen Boudicca, offered a frequent source of nationalist pride for British observers in the nineteenth century. William Mason had popularized the proto-Briton in his eighteenth-century poetry, and more recently, Scottish author William Stewart Ross had published a popular poem to “Caractacus the Briton” in 1881 (Ross). Many contemporary British readers would have been familiar with the story of both his defeat at the hands of a Roman invasion under Claudius, and his subsequent life-saving eloquence before the Senate after being led through a triumphal procession in the capital. While living in Rome after being spared execution, Caractacus is said to have inquired after the endless avarice of the Romans, noting that after all of their magnificence they still desired his people’s humble tents. To cast Cetshwayo in the role of the popular nationalist hero was both a provocative and powerful choice that revealed the ambivalences the British press felt toward the Zulu war and possibly the imperial project in southern Africa more generally. As The Saturday Review opined, “An exhibition of a defeated potentate can, at the worst, cause a passing scandal, which might be disregarded if it were accompanied by any considerable advantage.” Yet what was the advantage to be won in the presentation of this defeated monarch? (“Cetewayo’s Visit”).

Rome after his capture: “How is it possible that a people possessed of so much magnificence could begrudge me my humble kraal in Zululand?” (“Comic Papers”). Caractacus, like the Iceni queen Boudicca, offered a frequent source of nationalist pride for British observers in the nineteenth century. William Mason had popularized the proto-Briton in his eighteenth-century poetry, and more recently, Scottish author William Stewart Ross had published a popular poem to “Caractacus the Briton” in 1881 (Ross). Many contemporary British readers would have been familiar with the story of both his defeat at the hands of a Roman invasion under Claudius, and his subsequent life-saving eloquence before the Senate after being led through a triumphal procession in the capital. While living in Rome after being spared execution, Caractacus is said to have inquired after the endless avarice of the Romans, noting that after all of their magnificence they still desired his people’s humble tents. To cast Cetshwayo in the role of the popular nationalist hero was both a provocative and powerful choice that revealed the ambivalences the British press felt toward the Zulu war and possibly the imperial project in southern Africa more generally. As The Saturday Review opined, “An exhibition of a defeated potentate can, at the worst, cause a passing scandal, which might be disregarded if it were accompanied by any considerable advantage.” Yet what was the advantage to be won in the presentation of this defeated monarch? (“Cetewayo’s Visit”).

Depicting the Zulu king as the defeated Briton allowed the British to imagine themselves as a powerful and magnanimous imperial Rome, particularly in their generous hosting of Cetshwayo in 1882. Yet, it also opened questions of the legitimacy of the war and colonial control over Zululand. Certainly, the notion of imperial conquerors impressed by the resilience and martial prowess of the tribesman fighting for his homeland would flatter the metropolitan British observer, particularly the idea that the empire is rendered more valiant in having defeated a worthy foe. Indeed, this was the case in Thomas Lucas’ 1879 book, The Zulus and the British Frontiers, which had described Cetshwayo specifically in the trope of admirable but safely defeated barbarian, calling him a “Kaffir Caractacus” and even a “savage Owen Glendower” (Lucas 182). Still, the inherent criticism of imperial rapacity provides an unfavorable assessment of the very nature of the conquest. Significantly, Caractacus is very specifically a British hero; to place the Zulu king in such a place is to de-center the familiar norms of hero and villain, protagonist and antagonist. To depict Cetshwayo amid the gardens of ![]() Kensington or the imperial splendor of the royal family thus provides a substantial challenge to the narrative of British moral superiority and victory—it simultaneously reaffirms the martial skills of the Zulu warriors while undermining the implied greater power of the British in conquering them. By aligning Cetshwayo with Caractacus, British press writers did more than make a well-known classical allusion. They also subverted raced and gendered orders of empire by casting the British conquest as the product of an unrestrained (and therefore unmanly) display of avarice and undercut the racial difference between colonizer and colonized by making the ostensibly barbarous African a stand-in for their own valiant national ancestors.[5]

Kensington or the imperial splendor of the royal family thus provides a substantial challenge to the narrative of British moral superiority and victory—it simultaneously reaffirms the martial skills of the Zulu warriors while undermining the implied greater power of the British in conquering them. By aligning Cetshwayo with Caractacus, British press writers did more than make a well-known classical allusion. They also subverted raced and gendered orders of empire by casting the British conquest as the product of an unrestrained (and therefore unmanly) display of avarice and undercut the racial difference between colonizer and colonized by making the ostensibly barbarous African a stand-in for their own valiant national ancestors.[5]

In addition to providing novelty and interest for a metropolitan public, Cetshwayo’s visit brought the issue of restoration and of larger imperial interests firmly into the center of domestic conversations. The Saturday Review declared that Cetshwayo’s visit “would be an insignificant result of carelessness and bad judgment if it were not understood to imply a purpose for restoring him to power,” an act it described as “a question of international law, though that metaphorical branch of jurisprudence was scarcely intended to apply to a captive barbarian” (“Cetewayo’s Visit” 165). The description of Cetshwayo as a rude barbarian, a continuation of earlier press depictions of the king prior to 1880 and steeped generally in firmly racialized discourses of white supremacy, shifted slightly during his visit but never faded entirely from the surface of press reporting.

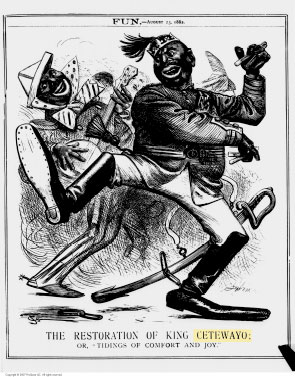

This is most apparent in the satirical periodical Fun’s depiction of the imperial dilemma resulting from Cetshwayo’s visit. The piece, titled “Very Busy (A Duet in Black and White),” began with an accompanying cartoon representing a meeting between John Bull and Cetshwayo, who was drawn in a style of black buffoonery, wearing but not quite effecting the civilizational aspirations offered by British clothing (see Fig. 1). Indeed, images of Cetshwayo in popular metropolitan media operated within pre-established tropes of comic black savagery; the picture in Fun was published in London on 3 August 1882—the very day that the monarch arrived in London. Arguably, then, Cetshwayo was simply slotted into this image before his very arrival. The titular poem rendered Cetshwayo fully within a global stereotype of black minstrelsy, speaking with a broad, stereotypical black accent:

Cetewayo and John Bull

C: How de do, sah? Hope you’re well, sah?

Poor old nigger’s turn at last;

Didn’t like de big sea-swell, sah,

Nebber mind, sah, dat is past;

Want to go back to my nation

Wid some dollars in my hat,

Glad to get your invitation.

Golly! Won’t we hab a chat!B. Ah! But I’m so very busy,

What with Egypt and the Turk

Why My head is growing dizzy

From this awful press of work:

Telegrams or long despatches

To be sent to ev’ry clime,

Troops and stores shipped oft in batches,–

Can’t you call another time? (“Very Busy”)

In addition to the casual racism, the piece presents a fascinating tableau for a metropolitan audience. While Cetshwayo is rendered idiotic and wheedling, the ultimate aims of the visit are made quite clear: the Zulu king has arrived to request restoration, something quite inconvenient to an overstretched British imperial state at present. The conversation is, therefore, offered as an admission of imperial limits—resources currently overcommitted to other global affairs—as affecting the decisions of British policy. The minstrel-king and the imperial Englishman offer a final meditation upon the Anglo-Zulu War itself in the closing lines, “We can’t always have our pleasures/For we’ve learned to our regret,/How that military measures/Nice arrangements may upset.” While papers covered both the pageantry and performance of the visit, the cartoon offered by a satirical paper illustrated the central concerns of the king’s visit—how to extricate both imperial and local entanglements caused by colonial military conflicts. Three weeks later, at the close of the king’s visit, the magazine published a similar image of Cetshwayo once again in minstrel-inspired clothing (in particular his playing the bones and sporting over-sized shoes, both standard in minstrel performances), celebrating his upcoming restoration (see Fig. 2). Even while reporting on the successful media tour of an African potentate, the editors at Fun depicted the king in stereotypical imagery that signified a larger sense of black male buffoonery.

Yet these minstrel-like images of Cetshwayo offer more than simple racist depictions of a foreign leader. They reveal a long-extant history of depictions of blackness within the British metropole that would have been immediately familiar to a contemporary reader of periodicals. Throughout the nineteenth century, a vast array of productions within British theaters offered spectators a glimpse of black figures, from abolitionist plays (particularly after the massive popularity of Stowe’s Uncle Tom’s Cabin) to the increasing popularity of visiting African performers (notably beginning with the 1811 arrival of Sarah Baartman as the ‘Hottentot Venus’ from the Cape Colony, and continuing throughout the century with Zulu and Xhosa performers). Indeed, Charles Dickens complained at length about a performance of Zulu dancers he attended in London in 1853 (Qureshi 183–184).[6] As the century wore on, black performers became a particularly lucrative enterprise in metropolitan theaters. Both the figure of the exotic Zulu savage and the carefree black minstrel were readily familiar idioms both on the British stage and in print media by the time of Cetshwayo’s 1882 arrival; the showman G. A. Farini attracted mass attention with his spectacles of “Friendly Zulus” in 1879 and “Cetewayo’s Daughters” (a show of African women) in 1882 (Durbach 149–150; on public spectacle, see also Durbach’s BRANCH article, “On the Emergence of the Freak Show in Britain”).[7]

The proliferation of both images, particularly the minstrel, represented a larger shift in depictions of black peoples in metropolitan Britain: from empathetic catalysts for political movements like abolition to figures of entertainment or comic relief. As Douglas Lorimer has argued, “the minstrel relied as much upon the sympathy as upon the contempt of his audience. One of the features of minstrel comedy was the imitation of the mannerisms of the wealthy and the well-connected. The humour came partly from the absurdity of the lowly black taking on the airs and graces of the refined, but also from a sense of identity with the minstrel who made fun of the pretentious” (Lorimer 44–45).

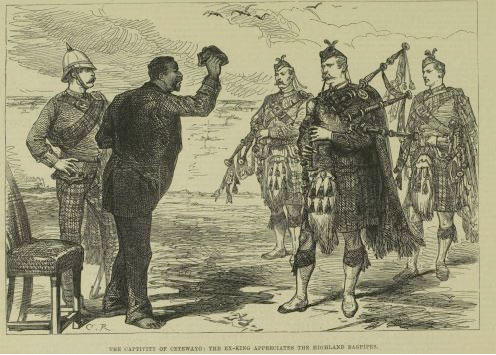

While this is undoubtedly true, these were not the sole images offered of Cetshwayo to a British reading public. Papers took pains to express the physical appearance of the king, particularly his quiet dignity and European dress (Codell 414–420). Indeed, during Cetshwayo’s previous imprisonment in the Cape Colony, the Illustrated London News offered an image of the king in full European dress being entertained by Scottish musicians (Fig. 3). Cetshwayo also received a caricature in the August 1882 issue of Vanity Fair and, like many important contemporaries, had a portrait taken by Alexander Bassano (Figs. 4 and 5). Both images were reproduced in periodicals and later publications; the Bassano portrait later appeared in Frances Colenso’s The Ruin of Zululand in 1885. These images offered another aspect of the king; clad in European clothing, he is at turns delighted, jovial, and dignified. Yet these images were not without an essentialist ‘othering.’ Both Bassano and Vanity Fair use headgear to mark Cetshwayo’s ultimate foreignness (the Zulu headring and the exotic tasseled hat, respectively, are used to clash with the ‘normality’ of European dress). Ultimately, depictions of the king vacillated between the prevailing popular stereotypes of minstrelsy and depictions of the king as a dignified royal personage on his visit to Queen Victoria.

Figure 4: “Restored” (Leslie Ward for _Vanity Fair_, 1882) and Figure 5: Photograph of Cetshwayo, 1882

Conclusion: Cetshwayo and the Stakes of Empire

The metropolitan press coverage of Cetshwayo’s visit also illustrated the profound differences between metropolitan views and those of settler elites in the neighboring colony of Natal. As the British public discussed the various merits of restoring Cetshwayo, the Natal Legislature emphatically denounced any and all attempts to return Cetshwayo to authority as a pronounced threat to settler order and colonial sovereignty. “I hope the world will know that none of us wish these chiefs back again,” thundered legislator J. C. Boshoff in 1881: “Let them have a pension if you like; let them sit at big dinners in London, but never let them come back to Natal again. Let them be an example to the other chiefs, that after once being sent away, they can never come back here” (Natal [Colony], Debates of the Legislative Council 1881 129). The Natal Legislature passed formal protests regarding the idea of Cetshwayo’s return to Zululand from 1880 to 1882, and continued to insist that to reinstate the Zulu king would undo the hegemony they wished to enact upon the land and peoples of both Natal and the semi-independent Zulu polity to the north. Recognizing the increasing popularity of the Zulu monarch in the British press, John Robinson attempted both a respectful tone towards Cetshwayo while denouncing his return as mischievous and threatening:

I say nothing against Cetywayo himself. I think he is to be greatly admired in many respects. He has borne his captivity in a way which would do credit to any civilized sovereign. I only desire that he shall be kept far apart from an opportunity of doing further mischief. If we look at the history of the world, we shall find that there are few instances of sending back conquered kings as vassal potentates. We know what happened after

Elba, and we know that history has endless repetitions (Natal [Colony], Debates of the Legislative Council 1881 186).

Robinson granted Cetshwayo a portion of begrudging credit for his ‘noble’ suffering, which resembles any ‘civilized sovereign’ (it goes without saying, however, that Robinson firmly implied that Cetshwayo was neither of these). By comparing Cetshwayo to Napoleon, Robinson hoped to highlight the danger and disruption of the king’s return, and seeks to convey to the imperial government the danger posed by such a return.

Ultimately, Cetshwayo’s return would be seen by Natal’s colonists as a fundamental abrogation of their presumed right over indigenous lands and bodies by a presumptuous British government. As usual, J. C. Boshoff put it most bluntly in the halls of the Legislature when he reflected upon Cetshwayo’s proposed release in 1880: “I hope that our beloved Queen will soon begin to get tired of the blacks, and that she will give them over in toto to the Colonists of South Africa, and say ‘I cannot do anything with them, and now I hand them over to you, the ![]() Transvaal, the Free State, the Cape Colony, and Natal; do with them as you like, but do not be too hard on them.’ If this were done we should soon have long and lasting peace.” (Natal [Colony], Debates of the Legislative Council, 1880 Pt. 2 226–27). To Boshoff’s inestimable disappointment, this was not to be the case. Many in the Colonial Office viewed their role, the ostensible protectors of indigenous interests, as acting counter to the wishes of rapacious settlers, and refused to give way, much to settler fury. Recognizing the anger of settlers in Natal at presumed British meddling, the satirical periodical Funny Folks neatly summed up the conflict between imperial government and settler state:

Transvaal, the Free State, the Cape Colony, and Natal; do with them as you like, but do not be too hard on them.’ If this were done we should soon have long and lasting peace.” (Natal [Colony], Debates of the Legislative Council, 1880 Pt. 2 226–27). To Boshoff’s inestimable disappointment, this was not to be the case. Many in the Colonial Office viewed their role, the ostensible protectors of indigenous interests, as acting counter to the wishes of rapacious settlers, and refused to give way, much to settler fury. Recognizing the anger of settlers in Natal at presumed British meddling, the satirical periodical Funny Folks neatly summed up the conflict between imperial government and settler state:

The ridiculous old Motherland is always getting into hot water with her distinguished South African descendants. First it is a Zulu war, which any number of Colonial Wellingtons, if you had only trusted them, could have finished in four days. And then the puny Imperial Government weakly declined to flay Cetywayo. . . . Observant students of our South African critics must by this time have come to the conclusion that the only safe way of dealing with South Africa is to let South Africa rule us. We cannot please them. They are always angry (“Angry South Africa”).

At its core, the Funny Folks article satirized the larger complaints of Natal’s settler class by taking them to their furthest conclusion—the idea that the colony can tell the ‘motherland’ ultimately what it should do. The debates characterized by both Funny Folks and the Natal Legislature around the fate of Cetshwayo reveal the larger questions of imperial sovereignty, settler power and indigenous autonomy extant in late nineteenth-century Britain and Natal.

To their inevitable disappointment, the protests of the settler legislators came to nothing; Cetshwayo was reinstated as king of the Zulu people in 1883. The Zulu monarch had successfully manipulated media discussion and mobilized discourses in his favor, and a newly appointed government under Gladstone was glad to acquiesce. However, Cetshwayo’s reinstatement was not a complete reversal of settler aims. While the imperial government returned the king in an about face on colonial policy of the previous years, Cetshwayo was only granted a third of his former lands. A third of the land to the south was established as a buffer state between Natal and the king in order to placate Africans who had sided against the king, and as a sop to the offended Natal government. The far more dangerous factor, however, was the formal establishment of an anti-Cetshwayo faction led by a rival, Zibhebhu. While settler leaders had been defeated in the immediate contest over imperial decision-making, Cetshwayo was left in a fundamentally precarious position upon his restoration in 1883. The king’s hard-fought victory was not to last. In 1883, Zibhebhu attacked and destroyed Cetshwayo’s main encampment at Ulundi, and the monarch fled into the forest, only to die a few short months later. It is this moment that historian Jeff Guy has considered to be the real destruction of the Zulu kingdom, rather than its defeat by the British in 1879. The rebellion of Zibhebhu against Cetshwayo and the subsequent civil war opened the kingdom to the competing interests of indigenous Africans, rapacious settlers, and opportunistic Boers from the Transvaal. Cetshwayo’s son, Dinizulu, was forced to acknowledge Boer claims to part of Zululand in order to gain forces necessary to defeat Zibhebhu, an echo of the complex political maneuvering his grandfather, Mpande kaSenzangakhona, had enacted a half century earlier. The chaotic fighting of the post-Cetshwayo period provided the pretext for the imperial government to formally acquire Zululand as a British colony in 1887. A decade later, Natal’s settlers seized their opportunity to annex Zululand outright as part of their colony, part of a larger move to establishing formal settler minority rule in the years after Responsible Government was achieved in 1893.

Despite the sharp reversals of Cetshwayo’s fortunes, the metropolitan print circulation of the Zulu king demonstrates the connection between discourses of race and masculinity and the larger political and social changes that resulted in colonial Natal. While Neil Parsons has characterized the impact of Cetshwayo’s visit to London as relatively insignificant in terms of political and social implications, this view is belied by the extraordinary success of his mission, even if it was short-lived (Parsons 119). The importance of the king’s 1882 visit cannot be measured in immediate political gains upon his return to Zululand, but rather in the sophisticated mobilization of discourses of race and gender that allowed an indigenous man to demonstrate that he was ‘every inch a king’ in the eyes of British public opinion and imperial estimation.

published February 2015

HOW TO CITE THIS BRANCH ENTRY (MLA format)

Tallie, T. J.. “On Zulu King Cetshwayo kaMpande’s Visit to London, August 1882.” BRANCH: Britain, Representation and Nineteenth-Century History. Ed. Dino Franco Felluga. Extension of Romanticism and Victorianism on the Net. Web. [Here, add your last date of access to BRANCH].

WORKS CITED

Altick, Richard Daniel. The English Common Reader: A Social History of the Mass Reading Public, 1800-1900. Chicago: U of Chicago P, 1957. Print.

Anderson, Catherine E. “A Zulu King in Victorian London: Race, Royalty and Imperialist Aesthetics in Late Nineteenth-Century Britain.” Visual Resources 24.3 (2008): 299–319. Print.

“Angry South Africa.” Funny Folks 3 Dec. 1881: n. pag. Print.

“Cetewayo at the Stake.” Saturday Review of Politics, Literature, Science and Art 26 Aug. 1882: 276–77. Print.

“Cetewayo in England.” Illustrated London News 12 Aug. 1882: 178. Print.

“Cetewayo’s Visit.” Saturday Review of Politics, Literature, Science and Art 5 Aug. 1882: 165–66. Print.

Codell, Julie F. “Imperial Differences and Culture Clashes in Victorian Periodicals’ Visuals: The Case of Punch.” Victorian Periodicals Review 39.4 (2006): 410–428. Print.

“Comic Papers.” Hampshire Telegraph and Sussex Chronicle etc 12 Aug. 1882: n. pag. Print.

Durbach, Nadja. Spectacle of Deformity: Freak Shows and Modern British Culture. Berkeley: U California P, 2009. Print.

Fraser, Hilary, Stephanie Green, and Judith Johnston. Gender and the Victorian Periodical. Cambridge: Cambridge UP, 2003. Print.

Kumar, Krishan. The Making of English National Identity. Cambridge: Cambridge UP, 2003. Print.

Lorimer, Douglas A.. “Bibles, Banjoes and Bones: Images of the Negro in the Popular Culture of Victorian England.” In Search of the Visible Past: History Lectures at Wilfrid Laurier University 1973-1974. Ed. Barry Gough. Waterloo, Ont.: Wilfrid Laurier UP, 1975. 31–50. Print.

Lucas, Thomas J. The Zulus and the British Frontiers. London: Chapman and Hall, 1879. Print.

Natal [Colony]. Debates of the Legislative Council of the Colony of Natal: First Session—Ninth Council, from October 20 to December 22, 1880. II. Pietermaritzburg: P. Davis and Sons, 1881. Print.

—. Debates of the Legislative Council of the Colony of Natal: Second Session—Ninth Council, from October 6, to December 14, 1881. III. Pietermaritzburg: P. Davis and Sons, 1882. Print.

Parsons, Neil. “‘No Longer Rare Birds in London’: Zulu, Ndebele, Gaza, and Swazi Envoys to England, 1882-1894.” Black Victorians, Black Victoriana. New Brunswick, N.J: Rutgers UP, 2003. 110–141. Print.

“Politics and Society.” The Leeds Mercury 4 Aug. 1882: n. pag. Print.

Porter, Bernard. The Absent-Minded Imperialists: Empire, Society, and Culture in Britain. Oxford: Oxford UP, 2004. Print.

Price, Richard. Making Empire: Colonial Encounters and the Creation of Imperial Rule in Nineteenth-Century Africa. Cambridge: Cambridge UP, 2008. Print.

Qureshi, Sadiah. “Meeting the Zulus: Displayed Peoples, British Imperialism and the Shows of London, 1853–1879.” Popular Exhibitions, Science and Showmanship, 1840–1914. Ed. Joe Kember, John Plunkett, and Jill Sullivan. London: Pickering and Chatto, 2012. 183–198. Print.

Ross, William Stewart. Lays of Romance and Chivalry. London: W. Stewart and Company, 1881. Print.

Tallie, T. J. “Queering Natal Settler Logics and the Disruptive Challenge of Zulu Polygamy.” GLQ: A Journal of Lesbian and Gay Studies 19.2 (2013): 167–189. glq.dukejournals.org.proxy2.library.illinois.edu. Web. 5 Mar. 2013.

“The Arrival of Cetywayo.” The Leeds Mercury 4 Aug. 1882: n. pag. Print.

—. The Bristol Mercury and Daily Post 4 Aug. 1882: n. pag. Print.

“The Captive King Cetewayo.” Illustrated London News 29 Nov. 1879: 512. Print.

“The Restoration of King Cetewayo Or, ‘Tidings of Comfort and Joy.’” Fun 23 Aug. 1882: 79–80. Print.

“The Triumph of Cetywayo.” Funny Folks 4 Oct. 1879: 316. Print.

“Very Busy: A Duet In Black and White.” Fun 2 Aug. 1882: 47–48. Print.

White, S. Dewe. “A Plea for Cetywayo.” Hampshire Telegraph and Sussex Chronicle etc 12 Aug. 1882: n. pag. Print.

ENDNOTES

[1] The defeat of the finest soldiers of the Empire at the hands of ‘savage’ warriors certainly can be viewed as a crisis of masculine authority for the British metropolitan reading public, one visible in the rhetoric of the metropolitan press.

[2] This is not to conflate circulation with readership; the increasing runs of published periodical material give a larger indication of readership, but no exact numbers. In addition, new periodicals such as the Illustrated London News (founded in 1842) capitalized on growing literacy rates in order to familiarize the metropolitan public with global news. The Anglo-Zulu War along with Cetshwayo’s capture and exile received extensive coverage in the Illustrated London News in 1879.

[3] This is not a universally held view among British historians. Bernard Porter and Richard Price have argued largely in favor of an insulated British public that was unaware and uninvolved in the acquisition of imperial territory. For Porter, such imperialism was ‘absent-minded,’ while for Price, it was evidence of a larger division between positive and insidious parts of imperialism. Yet the constancy with which imperial conquest and settlement figured in metropolitan texts leads me to conclude that imperialism was indeed an understood factor in contemporary metropolitan life.

[4] The gendered make-up of Cetshwayo’s entourage was almost certainly a conspicuous choice, so as to not provide further political ammunition with the apparent moral and social dilemma of Cetshwayo’s polygamous relationships being made visible. Indeed, the difficulties of polygamy in a state visit from a Zulu leader would still be a apparent over a century later when South African President Jacob Zuma arrived in London with his most recent bride—to the considerable consternation of the British press. See Tallie.

[5] Nor was this allusion-making unique to the metropolitan press; a sympathetic Natal Witness observed that upon his defeat, Cetshwayo, “although such a redoubtable enemy, he is admired by all. . . [while] his mien was that of a Caractacus” (Natal Witness 11 September, 1879).

[6] Dickens described the performance as “pantomimic expression which is quite settled to be the natural gift of the savage. . . conveys no idea to my mind beyond a general stamping, ramping and raving, remarkable (as everything in savage life is) for its dire uniformity.” He also decried that British audiences were “whimpering over [the savage] with maudlin admiration, and the affecting to regret him, and the drawing of any comparison of advantage between the blemishes of civilisation and the tenor of his swinish life” (Qureshi 177-78).

[7] These figures were quite popular for British entertainment. It would appear that metropolitan desire for a particularly imagined ‘authentic’ black figure led to a series of disreputable reproductions of both black minstrels and African performers, who were frequently Scots or Irishmen in forms of blackface.