Abstract

The British Empire Exhibition, held in 1924 and 1925, assembled the member nations of the empire to develop imperial trade connections and to cultivate closer political ties between Britain and her territories. A commercial, educational and imperial spectacle, the exhibition reminded Britons of the material and political value of the empire, as the nation struggled to recover from the economic impact of the Great War. For some colonial participants, however, the British Empire Exhibition enabled them to present a distinct national identity in pursuit of greater autonomy from Britain, while for others, it provided a forum in which to critique racial discrimination within the empire.

When it opened on 23 April 1924, the British press described the British Empire Exhibition as the largest and most important exhibition since 1851. Set in the north London suburb of ![]() Wembley and spread over 220 acres, this massive undertaking included commercial, technological and artistic displays, national pavilions, an amusement park, restaurants, cinemas and an artificial lake. Part trade fair and part theme park, it attracted approximately twenty-five million visitors over the two seasons that it remained open; seventeen million of them attended in 1924 alone. Advertised in the illustrated weekly newspaper The Graphic as the “gateway to the world,” the BEE assembled in one place the member nations of the British empire to celebrate imperial unity and to increase mutual economic cooperation (593). The Times reported that King George V, the grandson of Queen Victoria, opened the exhibition on St. George’s Day, 23 April 1924, before a crowd of approximately 100,000 people, many of whom were seated or standing in the new Empire Stadium (13). That concrete structure, which had opened the previous April 1923 to host the Football Association’s Cup Final, was the architectural focal point of the Wembley exhibition and, according to Alexander Geppert, the exhibition’s most important physical and cultural legacy (135-137).

Wembley and spread over 220 acres, this massive undertaking included commercial, technological and artistic displays, national pavilions, an amusement park, restaurants, cinemas and an artificial lake. Part trade fair and part theme park, it attracted approximately twenty-five million visitors over the two seasons that it remained open; seventeen million of them attended in 1924 alone. Advertised in the illustrated weekly newspaper The Graphic as the “gateway to the world,” the BEE assembled in one place the member nations of the British empire to celebrate imperial unity and to increase mutual economic cooperation (593). The Times reported that King George V, the grandson of Queen Victoria, opened the exhibition on St. George’s Day, 23 April 1924, before a crowd of approximately 100,000 people, many of whom were seated or standing in the new Empire Stadium (13). That concrete structure, which had opened the previous April 1923 to host the Football Association’s Cup Final, was the architectural focal point of the Wembley exhibition and, according to Alexander Geppert, the exhibition’s most important physical and cultural legacy (135-137).

In his opening remarks, the King described the British empire as a “family of nations.” This family included “white” settler dominions like ![]() Australia and

Australia and ![]() Canada; dependent colonies, such as

Canada; dependent colonies, such as ![]() Kenya and

Kenya and ![]() Uganda in British East Africa; protectorates, like

Uganda in British East Africa; protectorates, like ![]() Palestine and Malta; and

Palestine and Malta; and ![]() India, whose partial self-government under the 1919 Government of India Act confirmed the sub-continent’s ambiguous political status within the Empire as falling somewhere between a dominion and a colony.[1] The Times reported that King George spoke warmly of the need for “fraternal cooperation” (13) within this diverse group of nations, stating that he looked forward to a new prosperity and strength of unified purpose for the British empire after the difficult years of war and the current challenges of Britain’s post-war economic slump. The King’s opening speech was broadcast live by wireless radio on the new and still privately operated British Broadcasting Company, founded in 1922, to a listening audience of six million people who gathered in public parks and department stores to hear the monarch’s address. By all accounts, George V appeared delighted with the exhibition and visited it on several occasions.

India, whose partial self-government under the 1919 Government of India Act confirmed the sub-continent’s ambiguous political status within the Empire as falling somewhere between a dominion and a colony.[1] The Times reported that King George spoke warmly of the need for “fraternal cooperation” (13) within this diverse group of nations, stating that he looked forward to a new prosperity and strength of unified purpose for the British empire after the difficult years of war and the current challenges of Britain’s post-war economic slump. The King’s opening speech was broadcast live by wireless radio on the new and still privately operated British Broadcasting Company, founded in 1922, to a listening audience of six million people who gathered in public parks and department stores to hear the monarch’s address. By all accounts, George V appeared delighted with the exhibition and visited it on several occasions.

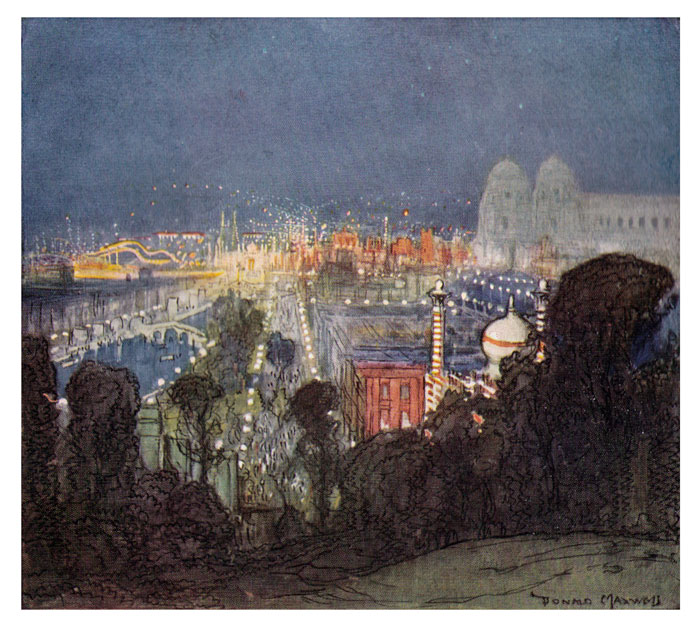

According to the British Empire Exhibition’s organizers, the exhibition was intended to inform the viewing public about the importance of maintaining strong imperial ties while illustrating the limitless wealth and potential of the empire’s resources. Extolling its merits as an educational device, the Official Guide claimed that visitors to the BEE learned more about the empire in a few days than they might have learned after months of travel. As a plebian tour of the empire, the exhibition democratized the idea of international travel making it “within the reach of all” at a cost of only eighteen pence (Lawrence 13). Donald Maxwell’s illustrated Wembley souvenir maintained this theme of exhibition travel by grouping his notes and sketches into five continents; “travelers” of the empire at Wembley were directed to specific panoramic views, seen to best advantage at different times of the day, evening or night (Figs. 1 and 2). Despite the exhibition’s size and thousands of attractions, Lawrence’s Official Guide informed visitors that it was possible to “do Wembley” in a single day, although three, or better yet, seven were needed for the full experience (33). Outlining itineraries for single and multi-day visits, top attractions included the Palace of Industry for the exhibits of consumer goods such as home appliances, fabrics, furnishings and processed foods. The Palace of Engineering was equally essential to inspect new technologies in the electrical, automotive and aeronautics industries. A quick tour of the dominion pavilions included stops in Canada, ![]() New Zealand and Australia, but not forgetting the Palace of Arts to admire Queen Mary’s famous doll’s house, a scale model of

New Zealand and Australia, but not forgetting the Palace of Arts to admire Queen Mary’s famous doll’s house, a scale model of ![]() Buckingham Palace (13-38). Stressing the educational benefits of a trip to the British Empire Exhibition for children and working-class families in particular, exhibition organizers directed promotional material at teachers, school boards, employers and trade unions.

Buckingham Palace (13-38). Stressing the educational benefits of a trip to the British Empire Exhibition for children and working-class families in particular, exhibition organizers directed promotional material at teachers, school boards, employers and trade unions.

“A Family of Nations”?

The organizers of the British Empire Exhibition intended that, after the difficult years of the war, the exhibition should strengthen imperial ties and foster greater economic cooperation among the member nations of the empire. Britons visiting the exhibition learned that theirs was an immense and wealthy global empire, rich in natural resources, agricultural products and industrial manufacturing. European markets for Britain’s exports may have collapsed in the wake of the Great War; however, increased trade within the empire had the potential to offset that deficit. The problem remained that, by the 1920s and in the aftermath of the Great War, the rhetoric of empire cooperation within a “Family of Nations” was not borne out in a meaningful way by the British Government and the Colonial Office. For example, despite the BEE’s mandate to further trade within the empire, in terms of its official policy, the British government still adhered to the long established orthodoxy of unregulated free trade. Proposals for the kind of tariff reforms that would have given preference to British dominions and colonies were discussed without resolution at the Imperial Conference in July 1923 and Stanley Baldwin’s Conservative government lost its majority when they put the tariff issue before British voters in late 1923 (Lloyd 111-113). Furthermore, in its effort to celebrate imperial unity, the British Empire Exhibition inadvertently encouraged the expression of national and political identities that questioned the existence of a unified and harmonious empire.

The experiences of Canada and India at the British Empire Exhibition are cases in point. Canada, as one of the self-governing “white” dominions, occupied a prominent place within the empire and the Wembley exhibition. For Canada, the BEE presented the chance not just to offer allegiance to Britain, but also to assert Canada’s own sense of national identity. For Canadian politicians and intellectuals, that sense of identity was increasingly tangible by the 1920s, having been strengthened by Canada’s military efforts during the Great War, the dominion’s representation at the 1919 ![]() Paris Peace Conferences, and its separate seats in the League of Nations. John Sylvester MacKinnon, the director of the Canadian Industrial Exhibits for the British Empire Exhibition, assured Canadian businessmen that they should participate in the exhibition to negotiate export contracts for their goods but also to demonstrate to the rest of the empire that Canada was a modern, industrial nation that was open for business.

Paris Peace Conferences, and its separate seats in the League of Nations. John Sylvester MacKinnon, the director of the Canadian Industrial Exhibits for the British Empire Exhibition, assured Canadian businessmen that they should participate in the exhibition to negotiate export contracts for their goods but also to demonstrate to the rest of the empire that Canada was a modern, industrial nation that was open for business.

To this end, the exhibits in the Canadian pavilion were both scenic and industrial with panoramic murals of farmland, mountains and forests, alongside working models of the ![]() Niagara Falls hydroelectric plant and dioramas of the ports in

Niagara Falls hydroelectric plant and dioramas of the ports in ![]() Vancouver and

Vancouver and ![]() Montreal. Approximately half of Canada’s pavilion was devoted to displays of goods by participating manufacturers anxious to increase exports to Britain. Prime Minister William Lyon Mackenzie King’s government allotted over one million dollars to the exhibition, despite skepticism on the part of some politicians and business groups who questioned the trade benefits of an expensive imperial exhibition when many Canadian manufacturers and resource companies looked south to the United States for market expansion (Clendinning 98). Given the notable absence of

Montreal. Approximately half of Canada’s pavilion was devoted to displays of goods by participating manufacturers anxious to increase exports to Britain. Prime Minister William Lyon Mackenzie King’s government allotted over one million dollars to the exhibition, despite skepticism on the part of some politicians and business groups who questioned the trade benefits of an expensive imperial exhibition when many Canadian manufacturers and resource companies looked south to the United States for market expansion (Clendinning 98). Given the notable absence of ![]() Québecois businesses and the noticeable lack of French-language didactics in the pavilion, French Canadians objected that the British Empire Exhibition was an expression of an Anglo-Canadian identity that overlooked the complexity of the nation’s dual history and culture. Although some French signage was hastily added after the exhibition opened, the damage had already been done. Public debates about Canada’s image at Wembley were revived in 1925. After virtually ignoring Canada’s aboriginal population in the 1924 exhibit, the following year, the Canadian organizers included a life-size tableau carved from Canadian butter, which featured Edward, the Prince of Wales dressed as a Stony chief, set in an “Indian” village which included native women, children and a tee-pee. This representation of Canada’s First Nations peoples as primitive and anti-modern contradicted the overarching theme of Canada as a modern and industrial nation, thereby provoking an indignant response from some Canadians, who questioned the confusing image of Canada that the organizers were presenting at the Wembley exhibition (Clendinning 92-93; 100-103).

Québecois businesses and the noticeable lack of French-language didactics in the pavilion, French Canadians objected that the British Empire Exhibition was an expression of an Anglo-Canadian identity that overlooked the complexity of the nation’s dual history and culture. Although some French signage was hastily added after the exhibition opened, the damage had already been done. Public debates about Canada’s image at Wembley were revived in 1925. After virtually ignoring Canada’s aboriginal population in the 1924 exhibit, the following year, the Canadian organizers included a life-size tableau carved from Canadian butter, which featured Edward, the Prince of Wales dressed as a Stony chief, set in an “Indian” village which included native women, children and a tee-pee. This representation of Canada’s First Nations peoples as primitive and anti-modern contradicted the overarching theme of Canada as a modern and industrial nation, thereby provoking an indignant response from some Canadians, who questioned the confusing image of Canada that the organizers were presenting at the Wembley exhibition (Clendinning 92-93; 100-103).

India’s participation in the British Empire Exhibition was designed to promote trade and to present the image of a nation moving towards modernization. Unlike Canada however, India’s political position within the empire was less clearly defined while continued discrimination against Indians by fellow dominion countries reflected the racial hierarchies that were inherent within this “family of nations.” In 1924, India occupied an ambiguous position within the empire, being neither an independent dominion nor a dependent colony. In 1919, India achieved partial self-rule under the terms of the Government of India Act that gave the sub-continent’s provincial legislatures some jurisdiction over selected departments and provided for elected Indian representatives. Although Indian troops had fought and died for Britain in Europe and the Middle East during the First World War, and India was a signatory of the League of Nations, Britain still denied India complete self-government, a sore point with Indian moderates and nationalists alike.[2] That sense of betrayal was exacerbated by the 1919 Amritsar Massacre, the brutal killing of 379 unarmed Indian demonstrators who had gathered in protest over the suspension of civil liberties in India. Despite these political tensions, Wembley’s organizing directors expected India to participate, and in 1921, they approached the India Office for assistance in securing exhibits of handicrafts, manufactured items and raw materials from the provinces and Indian states.

The provincial Directors of Industries agreed on the need for official participation and appointed an all-India Commissioner, Sir Tirubaliyangudo Vijayaraghavacharya, to oversee the arrangements. Supporters of the exhibition hoped that a successful display of India’s manufacturing and resources would develop trade and encourage investment while also creating a favorable impression with the British government that might further India’s movement towards greater self-rule. In contrast, Indian nationalists expressed their opposition to the imperial exhibition on the grounds that its object was the further exploitation of India’s natural resources for the benefit of foreign manufacturers and colonial plantation owners, with no indication of future political rewards for Indians. Daniel Stephen observes that calls to boycott the exhibition emerged in six provinces: Madras, the United Provinces, Bombay, Bengal, Bihar and Orissa, and the Punjab. However, their respective provincial assemblies passed resolutions in favor of participation (Stephen 176-78).

Vocal opposition to the exhibition was rekindled in the summer of 1923, amid preparations for India’s pavilion, with the release of the Devonshire Declaration, otherwise known as the Kenya White Paper. In their respective work, Daniel Stephen and Deborah Hughes note that the Devonshire Declaration was an attempt to suppress the political ambitions of Kenya’s white settler community and their demands for self-governance. In addition, by stating that the interests of Africans should take precedence over “the immigrant races,” the Devonshire Declaration undermined Kenya’s Indian population in their pursuit of equality with the white settlers (Stephen 179). Although the Devonshire Declaration officially put the interests of Africans before those of the Indian community, the policy was never intended to empower Africans but to suppress the agitation of Indians living in Kenya (Hughes 66-85). The Kenya White Paper, coinciding with the organization of the British Empire Exhibition, resulted in renewed calls from Indian nationalists to boycott the exhibition. Of the four Indian nationals sitting on the exhibition’s executive council in India, two resigned leaving the committee even more heavily dominated by Anglo-Indians.[3] In his official report regarding India’s participation, Commissioner Vijayaraghavacharya, noted that there was “considerable indignation” over the Kenya decision, making the Indian section of the Exhibition a “suitable scapegoat” for the errors of the Colonial Office (24). He wrote: “The Kenya decision certainly deprived the Exhibition of any lingering hopes of attracting popular enthusiasm, and it made the Exhibition officers feel that their work was being done in an uncomfortable atmosphere of popular disapproval, but it had no material influence on the success of the venture” (25).

As the above quote suggests, despite political tensions in India over the British Empire Exhibition, India’s pavilion was extremely popular with exhibition visitors, and the displays allegedly reaffirmed India’s loyalty to the empire. According to the Official Guide for the British Empire Exhibition, visitors were to understand that the Indian Pavilion tells the story of “British endeavor” (Lawrence 63), enabling Britons to grasp the difficulties encountered in the land reclamation schemes of ![]() Bombay, the development of “model factories” and the expansion of the railway. Reading the Official Guide, visitors learned this about India: “Everywhere the story is of progress, of the gradual overcoming of difficulties, of a victorious fight against ignorance, famine, flood and pestilence” (63). The official rhetoric applauded the achievements of the imperial project by inviting British visitors to take pride in the successes of the civilizing mission on the Indian subcontinent. This was not the message that the Indian provincial assemblies had hoped to communicate, but neither was it the reason that India declined to participate in 1925.

Bombay, the development of “model factories” and the expansion of the railway. Reading the Official Guide, visitors learned this about India: “Everywhere the story is of progress, of the gradual overcoming of difficulties, of a victorious fight against ignorance, famine, flood and pestilence” (63). The official rhetoric applauded the achievements of the imperial project by inviting British visitors to take pride in the successes of the civilizing mission on the Indian subcontinent. This was not the message that the Indian provincial assemblies had hoped to communicate, but neither was it the reason that India declined to participate in 1925.

“Races in Residence”

One of the most popular and controversial aspects of the British Empire Exhibition was the “Races in Residence” (Lawrence 126). According to the Official Guide, several of the colonial pavilions “have representatives of their local inhabitants at work in local conditions” (126) and it was apparently this commonality that qualified countries as different as Palestine and ![]() Hong Kong for inclusion in this descriptive category. Two hundred seventy three non-white colonized people from

Hong Kong for inclusion in this descriptive category. Two hundred seventy three non-white colonized people from ![]() Malaya,

Malaya, ![]() Burma, Hong Kong, West Africa and Palestine lived on the exhibition grounds for the duration of the event. For example, the West African walled compound housed seventy African men, women and children in a village setting. The Hong Kong exhibit was temporary home to one hundred seventy five Chinese occupants, who were recruited to London for the exhibition to run the Hong Kong shops and work as cooks, waiters and musicians at the exhibition’s Chinese food café. In addition, an unspecified number of Indians, Singhalese, West Indians and natives of British Guiana slept outside the exhibition but attended their respective pavilions during the day (126). The colonial residents also provided demonstrations of indigenous handicraft production and participated in cultural events, including performances of indigenous music and dance. By viewing the “races in residence,” visitors saw the wide spectrum of peoples and cultures contained within the British empire and in this respect the Wembley exhibition resembled the late Victorian and Edwardian colonial fairs with their well-publicized displays of foreign peoples.[4]

Burma, Hong Kong, West Africa and Palestine lived on the exhibition grounds for the duration of the event. For example, the West African walled compound housed seventy African men, women and children in a village setting. The Hong Kong exhibit was temporary home to one hundred seventy five Chinese occupants, who were recruited to London for the exhibition to run the Hong Kong shops and work as cooks, waiters and musicians at the exhibition’s Chinese food café. In addition, an unspecified number of Indians, Singhalese, West Indians and natives of British Guiana slept outside the exhibition but attended their respective pavilions during the day (126). The colonial residents also provided demonstrations of indigenous handicraft production and participated in cultural events, including performances of indigenous music and dance. By viewing the “races in residence,” visitors saw the wide spectrum of peoples and cultures contained within the British empire and in this respect the Wembley exhibition resembled the late Victorian and Edwardian colonial fairs with their well-publicized displays of foreign peoples.[4]

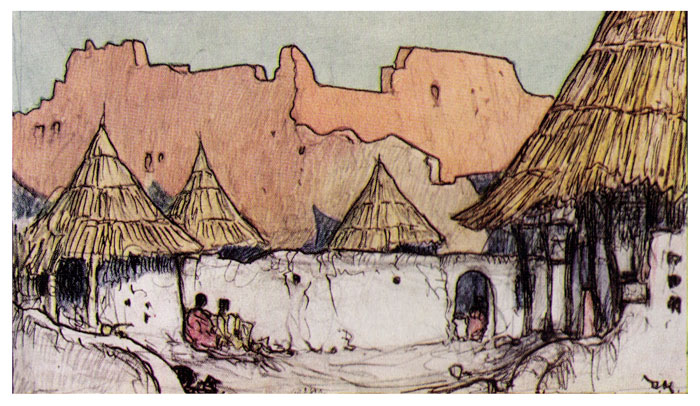

With its featured “Races in Residence,” the 1924 British Empire Exhibition continued an earlier tradition of displaying colonial people before the viewing public. (See, for example, Aviva Briefel, “On the 1886 Colonial and Indian Exhibition.”) The British Empire Exhibition differed slightly in that the individuals at Wembley lived in their respective national pavilions and were not primarily commercial sideshows located in the amusement sections, as they had been in pre-war imperial exhibitions. But notwithstanding this shift in emphasis that privileged education over entertainment, and the organizers’ concerted efforts to modernize the image of imperialism by emphasizing the importance of development and productivity instead of the older Victorian model of conquest and control, Wembley’s “Races in Residence” still underscored existing racial and cultural hierarchies that validated the colonial system. (See Fig. 3.)

Historian Daniel Stephen convincingly uses the example of the West African pavilion at the British Empire Exhibition to make this point. Displays in the West African “walled city” representing ![]() Sierra Leone,

Sierra Leone, ![]() Gold Coast and

Gold Coast and ![]() Nigeria, illustrated the alleged merits of colonial rule and British investment: the revival of traditional crafts; the cultivation of export crops, such as peanuts and cocoa; and the development of natural resources, including mineral extraction and forestry. In accordance with this message, the West African groups selected for inclusion in the “native village” and “native workshops”—for example, the Fulani, the Mendi and the Hausa—apparently embodied the qualities most valued by the British colonial administrators and missionaries, including industriousness, intelligence, the cultivation of community and conversion to Christianity (Stephen 111-114; 118-120). Out of concern for the welfare of the visiting Africans at Wembley, exhibition organizers arranged for the supply of familiar foodstuffs, for extra heating in the “native village” and for sightseeing trips on Sundays when the British Empire Exhibition was closed to the public (122).

Nigeria, illustrated the alleged merits of colonial rule and British investment: the revival of traditional crafts; the cultivation of export crops, such as peanuts and cocoa; and the development of natural resources, including mineral extraction and forestry. In accordance with this message, the West African groups selected for inclusion in the “native village” and “native workshops”—for example, the Fulani, the Mendi and the Hausa—apparently embodied the qualities most valued by the British colonial administrators and missionaries, including industriousness, intelligence, the cultivation of community and conversion to Christianity (Stephen 111-114; 118-120). Out of concern for the welfare of the visiting Africans at Wembley, exhibition organizers arranged for the supply of familiar foodstuffs, for extra heating in the “native village” and for sightseeing trips on Sundays when the British Empire Exhibition was closed to the public (122).

Although the West African press objected to the absence of Africans on the organizing committees, by and large, when it opened in April 1924, there was an initial general consensus that the exhibition represented a new era of prosperity and progress for the West African colonies within a British Empire that respected Africans and valued their contributions (Stephen 117). That sense of optimism evaporated in light of several derogatory articles, racist cartoons and misleading descriptions of life in West Africa that appeared in the British popular press in 1924. The outrage was compounded by the racial discrimination exercised by some London hoteliers who refused to accommodate African visitors. In response to these grievances and in protest over the public ridicule of Africans in the West African pavilion, the Union of Students African Descent (USAD) protested to the Colonial Office and held meetings to discuss West Africa’s future (Stephen 122-128). The Colonial Office objected that they had no power to control the press; however, the Governor of the Gold Coast, Sir F. Guggisberg, intervened to curtail public access to the West African village while the exhibition’s publicity council tried to prevent the future publication of derogatory articles (Adi 25-26). Although it was intended to “strengthen the bonds” between Britain and the colonies, the British Empire Exhibition became a flashpoint that motivated African students to protest against West Africa’s position in the empire, thereby laying the foundations for pan-African challenges to British colonial rule that developed during the 1930s and into the 1950s period of decolonization.

A Second Season: 1925

The British Empire Exhibition opened for a second season in May 1925, but only after considerable debate. Despite the enthusiastic press reports and the self-congratulatory comments of the exhibition organizers, the 1924 exhibition was a financial disaster. Executive director Sir William Travers Clark blamed the cold, rainy summer. Although 17 million people had passed through the turnstiles, that figure was much lower than the anticipated 30 million visitors that had been the basis for 1924’s projected returns. If only to try and recoup its investment, the British government agreed to re-open Wembley in 1925. After some initial hesitation, Australia, New Zealand, South Africa and Canada agreed to return for a second year, but only after the BEE commissioners offered them each a generous subsidy to defray their costs (Clendinning 97-100).

India was equally reluctant about 1925, officially for financial reasons but also because, in the opinion of the Viceroy, the provincial assemblies were unlikely to vote in support of the necessary funds, and probably for political reasons, the central government was unwilling to impose a decision. Vijayaraghavacharya expressed his unwillingness to co-ordinate India’s pavilion for a second year, an administrative vacuum that further undermined official resolution. But while the initial reservations of the settler dominions were overcome by financial incentives, the exhibition organizers in London failed to make India a similar offer, an inequity that troubled the Viceroy and India’s High Commissioner, who both saw this as a slight and worried about the political fallout should the subsidy issue become public.[5] To avoid embarrassment, the India Office and the Viceroy agreed to blame the exhibition committee whose prejudicial treatment of India could easily have been politicized by the nationalist cause. With no official participation by the Government of India in 1925, the British Empire Exhibition commission purchased the Indian pavilion and leased space to individual merchants thereby underscoring the image of India as an “oriental bazaar” and not a developing economy worthy of full dominion status.

In 1925, the “walled city” once again enclosed the pavilions of Nigeria, Gold Coast and Sierra Leone, and included the “native village.” As in 1924, West Africa’s white colonial administrators oversaw the execution of the display. This time around, however, the exhibition authorities in London took greater care to avoid offense to African visitors and exhibition participants by limiting direct contact with the public and the press and by omitting the descriptive subheading “races in residence” from the 1925 official guidebook (Lawrence 1925). In appears, despite these gestures, that West Africans paid less attention to the new and improved Wembley since the previous year’s display had already exposed the continued racial tensions within the empire, despite the official rhetoric of modernization and tolerance (Stephens, 127).

The British Empire Exhibition’s lasting legacy was the twin-towered sports stadium, closed in 2000 and later demolished despite its listed status at the borough level. More recently, the BEE appears in the 2010 film about the Duke of York’s stammer wherein Prince Bertie delivers a painful public address at the exhibition’s closing ceremony in October 1925.[6] In some respects, the future king’s faltering speech was an appropriate conclusion to these imperial exhibitions that had promised to strengthen imperial bonds, but had inadvertently illustrated the continued inequalities and existing tensions within this “family of nations.” On the other hand, despite the financial failures and political disappointments of the British Empire Exhibitions in 1924 and 1925, Wembley Stadium came to represent one of the great unifying symbols of Britain’s imperial past: sports, embodied in British football, rugby and cricket.

HOW TO CITE THIS BRANCH ENTRY (MLA format)

published August 2012

Clendinning, Anne. “On The British Empire Exhibition, 1924-25.” BRANCH: Britain, Representation and Nineteenth-Century History. Ed. Dino Franco Felluga. Extension of Romanticism and Victorianism on the Net. Web. [Here, add your last date of access to BRANCH].

WORKS CITED

Adi, Hakim. West Africans in Britain: 1900-1960: Nationalism, Pan-Africanism and Communism. London: Lawrence and Wishart, 1998. Print.

Auerbach, Jeffrey A. The Great Exhibition of 1851: A Nation on Display. New Haven and New York: Yale UP, 1999. Print.

Benedict, Burton. “Rituals of Representation: Ethnic Stereotypes and Colonized Peoples at World’s Fairs.” Fair Representations: World’s Fairs and the Modern World. Eds. Robert W. Rydell and Nancy Gwinn. Amsterdam: Vu UP, 1994: 28-58. Print.

Clark. T. “The British Empire Exhibition—Second Phase.” Nineteenth Century and After (February 1925): 176. Print.

Clendinning, Anne. “Exhibiting a Nation: Canada at the British Empire Exhibition, 1924-1925.” Histoire Sociale/Social History 39 (2006): 79-108. Print.

Coombes, Annie. Reinventing Africa: Museums, Material Culture and Popular Imagination in Late Victorian and Edwardian England. New Haven and London: Yale UP, 1994. Print.

De Mare, Eric. London 1851: The Year of the Great Exhibition. London: Folio Society, 1972. Print.

Embree, Ainslie T. India’s Search for National Identity. New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1972. Print.

“Gateway to the World”: advertisement for the British Empire Exhibition. The Graphic (12 April 1924): 552. Print.

Geppert, Alexander C. T. Fleeting Cities: Imperial Expositions in fin-de-Siècle Europe. Hampshire, England: Palgrave Macmillan, 2010. Print.

Greenhalgh, Paul. Ephemeral Vistas: The Expositions Universelles, Great Exhibitions and World’s Fairs, 1851-1939. Manchester: Manchester UP, 1988. Print.

Hoffenberg, Peter H. An Empire on Display: English, Indian, and Australian Exhibitions from the Crystal Palace to the Great War. Berkeley: U of California P, 2001. Print.

Hughes, Deborah L. “Kenya, India and the British Empire Exhibition of 1923.” Race & Class 47.4 (2006): 66-85. Scholars Portal. Web. 22 May 2012.

Illustrated London News 10 May 1924: 920. Print.

Knight, Donald R. and Alan D. Sabey. The Lion Roars at Wembley: British Empire Exhibition. London: Barnard & Westwood, 1984. Print.

Lawrence, G. C. ed. Official Guide to the British Empire Exhibition. London: Fleetway, 1924. Print.

—, ed. Official Guide to the British Empire Exhibition. London: Fleetway, 1925. Print.

Lloyd, T. O. Empire, Welfare State, and Europe: History of the United Kingdom, 1906-2001. Oxford: Oxford UP, 2002.

MacKenzie, John M. Propaganda and Empire: The Manipulation of British Public Opinion, 1880-1960. Manchester: Manchester UP, 1984. Print.

Maxwell, Donald. Wembley in Colour. London: Longmans, Green and Co., 1924. Print.

McIntyre, W. David. Colonies into Commonwealth. London: Blandford Press, 1974. Print.

Pugh, Martin. State and Society: A Social and Political History of Britain, 1870-1997. London: Arnold, 1994. Print.

Qureshi, Sadiah. Peoples on Parade: Exhibitions, Empire, and Anthropology in Nineteenth-Century Britain. Chicago: U of Chicago P, 2011. Print.

Rydell, Robert W. World of Fairs: The Century-of-Progress Expositions. Chicago: U of Chicago P, 1993. Print.

Stephen, Daniel M. “‘The White Man’s Grave’: British West Africa and the British Empire Exhibition of 1924-1925.” Journal of British Studies 48.1 (January 2009): 102-128. Print.

—. “‘Brothers of the Empire’?: India and the British Empire Exhibition of 1924-25.” Twentieth -Century British History 22. 2 (2011): 164-188. Print.

Vijayaraghavacharya, Tirubaliyangudo. The British Empire Exhibition, 1924: Report by the Commissioner for India for the British Empire Exhibition. Calcutta: Government of India P, 1925. Print.

“Wembley: An Historic Ceremony.” The Times 24 April 1924: 13. Microfilm.

RELATED BRANCH ARTICLES

Aviva Briefel, “On the 1886 Colonial and Indian Exhibition”

Audrey Jaffe, “On the Great Exhibition”

Anne Helmreich, “On the Opening of the Crystal Palace at Sydenham, 1854″

ENDNOTES

[1] In 1917, Edwin Montagu, Secretary of State for India, and Lord Chelmsford, the Viceroy of India, recommended to the House of Commons that Indians should be included in every branch of administration moving towards legislation reform and the progressive development of self-government. Theses reforms were formalized in the 1919 Government of India Act. For further discussion, see McIntyre 188-189.

[2] Pugh 239-241; see also Embree 59-61.

[3] Jamnadas Dwarkanath and Srinivase Sastri resigned from the executive council; see Vijayaraghavacharya 24.

[4] For further reading about Victorian exhibitions and displayed peoples, see Coombes 88-97; Hoffenberg 146-147; MacKenzie 103-14; Benedict 29-35; and Qureshi.

[5] For the discussion of India’s participation in 1925 and controversial cash subsidy, see the correspondence between the Viceroy and the Secretary of State for India, British Library/IOR/L/E/L/1186, File 102 (ii), folios 650, 689, 53, 554, 511, 515-518, 523-27.

[6] The King’s Speech. Dir. Tom Hooper. UK Film Council, See-Saw Films, Bedlam Productions, 2010.