Abstract

The meeting between Henry Morton Stanley and Dr. David Livingstone in Africa was one of the most sensational news stories of the nineteenth century. Stanley’s greeting, “Dr. Livingstone, I presume?” is still a well known phrase. The Scottish missionary had been out of contact for several years when an American newspaper sent its correspondent to search for him. The meeting turned public attention to the African slave trade and was a pivotal moment in the relationship among the United States, Europe, and Africa.

Stanley traveled to Africa in October 1870 to find Livingstone before anyone else. ![]() The Royal Geographical Society (RGS) in Britain had already sent one expedition to find Livingstone in response to rumors of his death in 1866, and it sent a second search party there at the same time as Stanley. No news had been received from Livingstone back in Britain since a letter dated 30 May 1869. Many assumed he was dead. The New York Herald suspected that the first sighting of Dr. Livingstone would be an extraordinary story. According to Stanley, the paper had given him the following assignment: “Find out Livingstone, and get what news you can relating to his discoveries” (qtd. in Bennett 3). The Herald was one of the first newspapers in the

The Royal Geographical Society (RGS) in Britain had already sent one expedition to find Livingstone in response to rumors of his death in 1866, and it sent a second search party there at the same time as Stanley. No news had been received from Livingstone back in Britain since a letter dated 30 May 1869. Many assumed he was dead. The New York Herald suspected that the first sighting of Dr. Livingstone would be an extraordinary story. According to Stanley, the paper had given him the following assignment: “Find out Livingstone, and get what news you can relating to his discoveries” (qtd. in Bennett 3). The Herald was one of the first newspapers in the ![]() United States to expand coverage beyond political affairs to entertaining “human interest” stories of questionable news value in order to reach a mass audience (Crouthamel x). Its editors, who had a reputation for racially insensitive and staunchly anti-British views, foresaw a major scoop when they arranged for a correspondent to go to Africa in search of the missing explorer.

United States to expand coverage beyond political affairs to entertaining “human interest” stories of questionable news value in order to reach a mass audience (Crouthamel x). Its editors, who had a reputation for racially insensitive and staunchly anti-British views, foresaw a major scoop when they arranged for a correspondent to go to Africa in search of the missing explorer.

Africa became increasingly important to European commercial and humanitarian interests during the nineteenth century. The shift was dramatic: “In 1800 most Africans had seen few if any Europeans. In 1900 nearly all of Africa was ruled by Europe” (McCaskie 687). However, little was known about the African interior until technological and medical advances made it possible for Europeans to overcome the continent’s formidable geography. Stanley referred to Africa as the “Dark Continent” in the title of one of his books (Through the Dark Continent). The term was first used by missionaries to describe a spiritual darkness in need of the Gospel’s light. For others, the phrase evoked the continent’s unmapped geography, the skin color of its inhabitants, or even the high death toll. Many previous explorers from Europe had died while trying to open up the continent to outside eyes. More than half of the men perished on the four British expeditions sent to Africa prior to Stanley’s arrival, including the disastrous Zambezi expedition (1858-64) led by Livingstone. Transport was difficult since rapids and sandbanks obstructed the waterways, and draft animals were susceptible to the bite of the tsetse fly. Diseases such as malaria, sleeping sickness, and yellow fever remained serious threats even after the introduction of medicines like quinine. Livingstone himself suffered twenty-seven attacks of malaria during his coast-to-coast journey across Africa (1853-56).

Stanley reached Africa’s eastern coast on 6 January 1871. Once there, he assembled a caravan of over a hundred men to carry trade goods and equipment into the interior. Stanley led the caravan on an Arab stallion. The group traveled for eight months through hazardous territory beset by tribal conflicts, losing many men to illness and desertion along the way, before hearing rumors of a white man staying at a nearby village.

The reports of Livingstone’s death were untrue. Livingstone was still alive, but he was badly in need of resources. Gaunt from dysentery and hobbled by foot ulcers, he was stranded without medicine or supplies in ![]() Ujiji, an Arab settlement on the eastern coast of

Ujiji, an Arab settlement on the eastern coast of ![]() Lake Tanganyika. Nearly all of his followers had deserted him, and he was demoralized after witnessing a massacre of hundreds by the Arab slave traders at

Lake Tanganyika. Nearly all of his followers had deserted him, and he was demoralized after witnessing a massacre of hundreds by the Arab slave traders at ![]() Nyangwe. Stanley arrived in Ujiji five days after Livingstone, in either October or November 1871 (the precise date is unknown).

Nyangwe. Stanley arrived in Ujiji five days after Livingstone, in either October or November 1871 (the precise date is unknown).

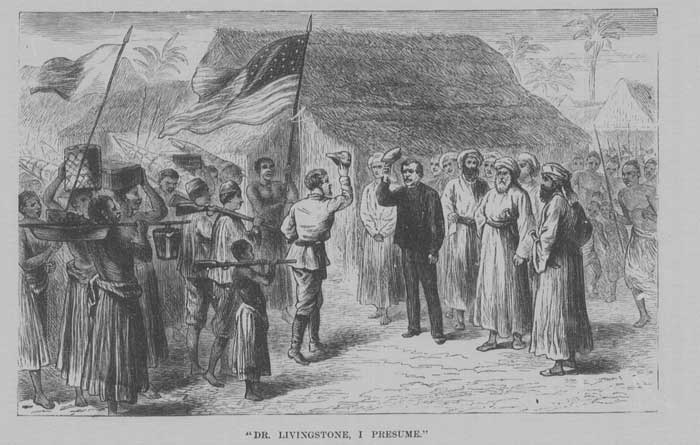

Stanley’s caravan entered Ujiji brandishing the American flag and firing rifles in salute. It was here that Stanley encountered the explorer who had been “missing” for so many years. Stanley recalled the moment in his dispatches: “Passing from the rear of [the expedition] to the front I saw a knot of Arabs, and, in the centre, in striking contrast to their sunburnt faces, was a pale-looking and gray-bearded white man, in a navy cap, with a faded gold band about it, and red woolen jacket. This white man was Dr. David Livingstone, the hero traveller, the object of the search” (Bennett 51). The two men raised their hats to one another and then shook hands. The scene of the two explorers meeting for the first time was memorably depicted in newspapers, magazines, and in Stanley’s How I Found Livingstone: Travels, Adventures, and Discoveries in Central Africa (1872). (illus. 1) They spent four months together, undertaking a joint expedition to the northern coast of Lake Tanganyika before Stanley returned to Britain with news of the meeting. Livingstone stayed behind to continue his search for the source of the ![]() Nile. The two men never met again as Livingstone died the following year.

Nile. The two men never met again as Livingstone died the following year.

[Illustration 1: Engraving of Stanley’s meeting with Livingstone from How I Found Livingstone (1872). Stanley, Henry M., How I Found Livingstone: Travels, Adventures and Discoveries in Central Africa: Including an Account of Four Months’ Residence with Dr. Livingstone. New York: Scribner, Armstrong, & Co., 1872. Engraving facing p. 412]

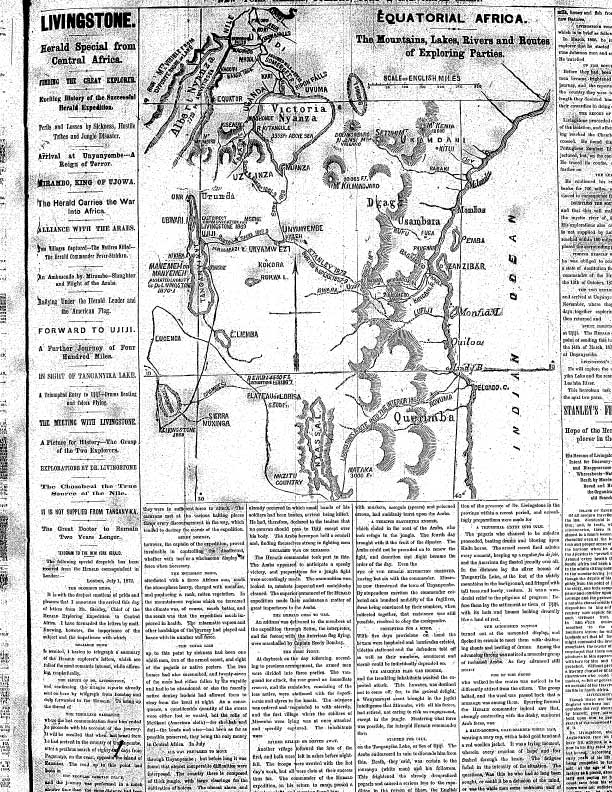

Stanley’s meeting with Livingstone was one of the most sensational news stories of the nineteenth century. The New York Herald reported the meeting on 2 July 1872. News of the event covered the paper’s entire third page, on which a large map of equatorial Africa appeared alongside twenty-two headings running down the left-hand column of the page:LIVINGSTONE.

——————

Herald Special from Central Africa.

——————

FINDING THE GREAT EXPLORER.

——————

Exciting History of the Successful Herald Expedition.

——————

Perils and Losses by Sickness, Hostile Tribes and Jungle Disaster.

——————

Arrival at

Unyanyembe—A Reign of Terror.

——————

MIRAMBO, KING OF UJOWA.

——————

The Herald Carries the War Into Africa.

——————

ALLIANCE WITH THE ARABS.

——————

Two Villages Captured–The Natives Killed–The Herald Commander Fever-Stricken.

——————

An Ambuscade by Mirambo–Slaughter and Flight of the Arabs.

——————

Rallying Under the Herald Leader and the American Flag.

——————

FORWARD TO UJIJI.

——————

A Further Journey of Four Hundred Miles.

——————

IN SIGHT OF TANGANYIKA LAKE.

——————

A Triumphal Entry to Ujiji–Drums Beating and Colours Flying.

——————

THE MEETING WITH LIVINGSTONE.

——————

A Picture for History–The Grasp of the Two Explorers.

——————

EXPLORATIONS BY DR. LIVINGSTONE.

——————

The

Chambezi the True Source of the Nile.

——————

IT IS NOT SUPPLIED FROM TANGANYIKA.

——————

The Great Doctor to Remain Two Years Longer. (“Livingstone”)

[Illustration 2: The New York Herald, 2 July 1872.]

Beneath the headings, the Herald announced that it had received the following dispatch from its London correspondent: “THE GLORIOUS NEWS. It is with the deepest emotions of pride and pleasure that I announce the arrival this day of letters from Mr. Stanley, Chief of the HERALD Exploring Expedition to Central Africa” (“Telegram”). The announcement preceded a summary of Stanley’s letters supplying a detailed narrative of the African expedition. A vivid account of the climactic event appeared under the heading “A HISTORIC MEETING”:Preserving a calmness of exterior before the Arabs which was hard to simulate as he reached the group, Mr. Stanley said:–“Doctor Livingstone, I presume?”

A smile lit up the features of the hale white man as he answered:–

“YES, THAT IS MY NAME.” (“Telegram”)

The evening papers across the United States reprinted the news, and the Herald informed readers on the following day that all of the American and British papers had reported the triumph. It was one of the first major stories to be told simultaneously on both sides of the Atlantic, thanks to the copper telegraph cable that had been laid across the ocean floor in 1866.

“Dr. Livingstone, I presume?” is one of the most well known phrases in the history of journalism. Stanley’s greeting was the source of endless mirth back in America and Europe, where the phrase became a punchline in clubs, pubs, and music halls. Audiences found it amusing to hear a formal introduction used at such an emotionally charged moment in the middle of the African jungle. American audiences laughed at the spectacle of one of their journalists mimicking English customs while at the same time triumphing over rivals in the race to find Livingstone. English audiences reveled in the awkward imitation of a gentleman by a Yankee while at the same time regretting their own search party’s ineffectiveness. Stanley explained afterward that he had been unsure whether it was truly Dr. Livingstone standing before him. Ironically, Stanley might not even have spoken the phrase on which so much of his fame rests. Biographer Tim Jeal concludes that he did not, and attributes the invented phrase to Stanley’s insecurity about an impoverished Welsh background that he concealed for most of his life (117). There is no way of knowing for sure since the relevant page in Stanley’s diary is torn out. At any rate, the press widely reported the memorable phrase and lodged it indelibly in public memory.

American and British newspapers continued to report on Stanley’s meeting with Livingstone throughout the summer of 1872. The two countries nevertheless emphasized very different aspects of the story. The British press emphasized the issue of the African slave trade and the horrific details of the Nyangwe massacre witnessed by Livingstone prior to Stanley’s arrival. Livingstone’s revelations played a major role in raising public awareness of racial and imperial issues in Africa; his account of the massacre was submitted to Parliament and led directly to the closure of the slave market in Zanzibar the following year. By contrast, the American press celebrated the expedition as a national triumph. It was as much a commercial as a humanitarian achievement for the New York Herald, which seized the opportunity to claim credit for what had begun as a solely British endeavor. The Herald prominently displayed the letter from Livingstone expressing gratitude toward the American rescue expedition.

The rescue of a British public figure by an American newspaper was an occasion for hand-wringing among the press in England. The Daily Telegraph correspondent who interviewed Stanley on his way back from Africa expressed regret at finding Stanley to be an American (Stanley was still concealing his Welsh background at the time). The Illustrated London News observed: “What the expedition organised by the Royal Geographical Society failed to accomplish, Mr. Stanley, representing nothing more than the energy and the pecuniary credit of the New York Herald, has had the good fortune to compass single-handed” (“Finding” 98). The press lamented the decline in British nerve following a long tradition of heroic explorers from Francis Drake to Richard Burton.

Some publications even refused to accept the reports coming out of Africa. The magnitude of the story led journalists on both sides of the Atlantic to question the story’s authenticity, even to suspect a hoax. The Standard was the first to suggest that Stanley may have forged Livingstone’s letters. Newspapers circulated allegations of fraud alongside charges that the interview itself was a fabrication. At least one publication accused Stanley of inventing the encounter after finding the dead explorer’s belongings. Others suspected the Herald itself of manufacturing the controversy in order to sell newspapers (Rubery 508). Confirmation from Livingstone’s family was necessary to dispel doubts about the veracity of Stanley’s account.

The story came at an opportune moment for diplomacy. The handshake between Stanley and Livingstone provided a sorely needed image of Anglo-American unity after the bitter divisions opened up by the American Civil War. Britain had only recently settled reparation claims with the Union for support (despite an official position of neutrality) given to the pro-slavery Confederacy. The meeting between the two men was a chance to re-establish an Anglo-American alliance based on the shared value of freedom across the globe (Pettitt 12). Livingstone’s lifelong campaign against the slave trade made him a powerful symbol of unity. Capitalizing on the fact that America had abolished slavery at home, Livingstone’s letters to the New York Herald asked for help in combating the slave trade in Africa: “Now that you have done with domestic slavery forever, lend us your powerful aid towards this great object” (qtd. in Hall 197). The prominence of the American flag in illustrations of the famous meeting appearing in publications throughout North America and Europe reinforced this image of transatlantic unity.

The meeting between Stanley and Livingstone captured the attention of readers who paid little attention to international affairs. Yet it is difficult to determine how representative Livingstone’s story was of Britain’s imperial agenda. The British presence in Africa was a minor one for much of the nineteenth century. Prior to 1872, policymakers viewed Africa largely in terms of coastal trading posts, transport routes to ![]() India and the East, or humanitarian interventions to stop the slave trade. Missionaries such as Livingstone were exceptional in their aspirations to civilize Africa through trade, education, and Christianity. The failure of such humanitarian efforts led to a more pessimistic view of the continent in subsequent decades. The previous generation’s confidence was difficult to maintain when confronted with the poor record of Christian converts, the failure to develop commerce, and the persistence of the slave trade. The Partition of Africa, or annexation of African territory among European nations between 1881 and 1914, resulted in a shift from military and economic influence to direct rule in many cases. By 1911, Britain’s colonial expansion had resulted in the acquisition of territory in every quarter of the continent (Newbury 626). The expansion went together with a shift in attitudes towards Africa and Africans, often inflected by an increasing racial awareness. The view that Africans stood little chance of governing themselves gained in prominence. The sense of European superiority was reinforced by imperial gains in other parts of the globe and the rise of a pseudo-scientific racism that laid the groundwork for the Imperial Age in Africa.

India and the East, or humanitarian interventions to stop the slave trade. Missionaries such as Livingstone were exceptional in their aspirations to civilize Africa through trade, education, and Christianity. The failure of such humanitarian efforts led to a more pessimistic view of the continent in subsequent decades. The previous generation’s confidence was difficult to maintain when confronted with the poor record of Christian converts, the failure to develop commerce, and the persistence of the slave trade. The Partition of Africa, or annexation of African territory among European nations between 1881 and 1914, resulted in a shift from military and economic influence to direct rule in many cases. By 1911, Britain’s colonial expansion had resulted in the acquisition of territory in every quarter of the continent (Newbury 626). The expansion went together with a shift in attitudes towards Africa and Africans, often inflected by an increasing racial awareness. The view that Africans stood little chance of governing themselves gained in prominence. The sense of European superiority was reinforced by imperial gains in other parts of the globe and the rise of a pseudo-scientific racism that laid the groundwork for the Imperial Age in Africa.

Stanley undertook the expedition to find Livingstone in Africa in order to make a sensational headline for the press. He had little idea that the meeting with Livingstone would turn out to be a pivotal moment in the history of exploration and the future colonization of Africa. Stanley’s account of the meeting contributed to the iconic image of Dr. Livingstone that inspired numerous settlers to travel to the continent in his footsteps. The myth of Livingstone as a saintly Christian missionary singlehandedly combating the slave trade in Africa persisted even though Livingstone failed to make a single lasting convert to Christianity or to accomplish his goal to locate the source of the Nile. When Livingstone died in 1873, his remains were returned to Britain and ceremoniously interred at ![]() Westminster Abbey. Stanley was a pallbearer at the funeral. Now a celebrity himself, Stanley returned to Africa to cover the British campaign against the Ashanti in 1873 and again in 1874, after Livingstone’s death, to pursue the geographical questions about Central Africa left unresolved by previous explorers.

Westminster Abbey. Stanley was a pallbearer at the funeral. Now a celebrity himself, Stanley returned to Africa to cover the British campaign against the Ashanti in 1873 and again in 1874, after Livingstone’s death, to pursue the geographical questions about Central Africa left unresolved by previous explorers.

HOW TO CITE THIS BRANCH ENTRY (MLA format)

published March 2012

Rubery, Matthew. “On Henry Morton Stanley’s Search for Dr. Livingstone, 1871-72.” BRANCH: Britain, Representation and Nineteenth-Century History. Ed. Dino Franco Felluga. Extension of Romanticism and Victorianism on the Net. Web. [Here, add your last date of access to BRANCH].

WORKS CITED

Bennett, Norman R., ed. Stanley’s Despatches to the New York Herald, 1871-1872, 1874-1877. Boston: Boston UP, 1970. Print.

Crouthamel, James L. Bennett’s New York Herald and the Rise of the Popular Press. Syracuse: Syracuse UP, 1989. Print.

“The Finding of Dr. Livingstone.” Illustrated London News. 3 Aug. 1878, 98. The Illustrated London News Historical Archive 1842-2003. Gale Cengage. Accessed Dec. 7, 2011.

Hall, Richard Seymour. Stanley: An Adventurer Explored. Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1975. Print.

Jeal, Tim. Stanley: The Impossible Life of Africa’s Greatest Explorer. London: Faber and Faber, 2007. Print.

“Livingstone.” New York Herald. 2 Jul. 1872. 3. Microfilm.

Livingstone, David. Missionary Travels and Researches in South Africa. New York: Harper & Brothers Publishers, 1858. Print.

McCaskie, T.C. “Cultural Encounters: Britain and Africa in the Nineteenth Century.” Porter 665-89.

Newbury, Colin. “Great Britain and the Partition of Africa, 1870-1914.” Porter 624-50.

Pettitt, Clare. Dr Livingstone, I Presume? Missionaries, Journalists, Explorers, and Empire. London: Profile Books, 2007. Print.

Porter, Andrew, ed. The Nineteenth Century. Oxford: Oxford UP, 1999. Print. Vol. 3 of The Oxford History of the British Empire. 5 vols. 1998-1999. Print.

Rubery, Matthew. “A Transatlantic Sensation: Stanley’s Search for Livingstone and the Anglo-American Press.” U.S. Popular Print Culture: 1860-1920. Ed. Christine Bold. Oxford: Oxford UP, 2011. 501-518. Print. Vol. 6 of The Oxford History of Popular Print Culture. 6 vols. 2011.

Stanley, Henry M. How I Found Livingstone: Travels, Adventures and Discoveries in Central Africa: Including an Account of Four Months’ Residence with Dr. Livingstone. New York: Scribner, Armstrong, & Co., 1872. Print.

—. Through the Dark Continent; Or, The Sources of the Nile around the Great Lakes of Equatorial Africa and Down the Livingstone River to the Atlantic Ocean. London: Sampson Low, Searle, Rivington, 1878. Print.

“Telegram to the New York Herald.” New York Herald. 2 Jul. 1872. 3. Microfilm.