Abstract

This article offers a critical reading of who was sent to Sierra Leone, why West Africa was chosen as the destination, and discusses the larger meanings, contexts, and legacies of the “Province of Freedom.”

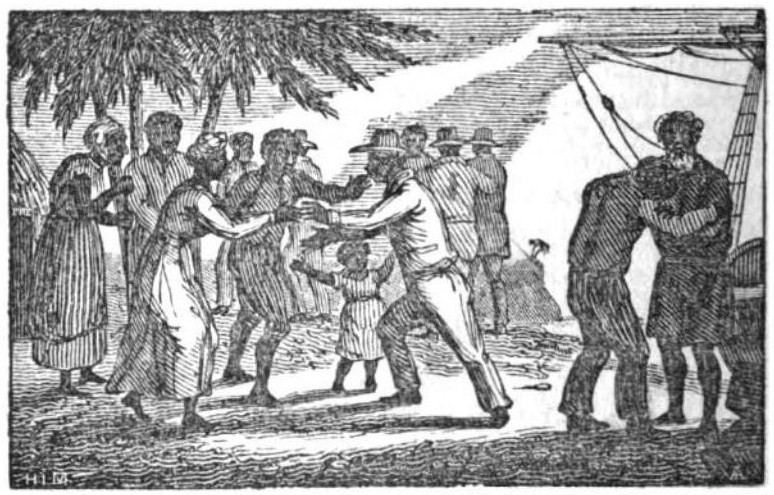

On 9 April 1787, 451 people set sail to establish a “Province of Freedom” in Africa. Most had been destitute on the streets of London until a private charity, the Committee for the Relief of the Black Poor, began to supply outdoor relief, although this was rejected as a long-term solution. In partnership with the British government,

An uneasy and contentious collaboration between philanthropists, antislavery activists and self-emancipated former slaves, Sierra Leone had to be refounded, or reinvented, several times before it found a secure footing. Fresh infusions of approximately 1,200 black loyalists from ![]() Nova Scotia in 1792, and 550 Jamaican Maroons in 1800, would make up for demographic losses but also added new sources of contention. By this time, the early utopian aspects of the project had been abandoned, and

Nova Scotia in 1792, and 550 Jamaican Maroons in 1800, would make up for demographic losses but also added new sources of contention. By this time, the early utopian aspects of the project had been abandoned, and ![]() Freetown was administered by the Sierra Leone Company, which minted coins and built a fort. The settlement reached a population of about 2,000 in 1808, when it became a Crown Colony and the policy of landing “recaptives” there gave the project a new stability and coherence; more than 50,000 slaves, intercepted and liberated by the Royal Navy, would begin new lives in Freetown over the next six decades.

Freetown was administered by the Sierra Leone Company, which minted coins and built a fort. The settlement reached a population of about 2,000 in 1808, when it became a Crown Colony and the policy of landing “recaptives” there gave the project a new stability and coherence; more than 50,000 slaves, intercepted and liberated by the Royal Navy, would begin new lives in Freetown over the next six decades.

Antislavery visionaries believed Sierra Leone was part of God’s plan to allow Britain to atone for its part in the slave trade, as well as a historically memorable instance of how an empire could use its superpower status in a selfless manner. Freetown’s actual black settlers saw the new community not as a tidy moment of expiation and closure for others, but as a new milestone on a timeline of their own devising, which began with their self-emancipation and continued in the search for dignity and full self-determination.

Why ship free black imperial subjects to a new African settlement? Was the West African coast a plausible location for a Province of Freedom? The initial scheme, initiated two decades before Britain’s move to abolish the Atlantic slave trade in 1807, struck some as implausible and even reckless. As Ottobah Cugoano put it, “can it be readily conceived that [the British] government would establish a free colony for them nearly on the spot [where] it supports its forts and garrisons, to ensnare, merchandize, and to carry others into captivity and slavery”? (Cugoano 156). This wary response should remind us that there was little reason, in the 1780s, to foresee that Freetown would prosper as part of a coherent, well-financed plan, backed by military force, to end the slave trade and transform West Africa. Indeed, the original projectors also considered sending the Black Poor to the ![]() Bahamas, to

Bahamas, to ![]() New Brunswick, and possibly even to

New Brunswick, and possibly even to ![]() Australia. Rather than accepting the back-to-Africa trajectory as a given, this article places the founding of Sierra Leone in that broader, often forgotten context, considering alternatives and paths not taken, as well as exploring some of the reasons why the risky Africa project went forward.

Australia. Rather than accepting the back-to-Africa trajectory as a given, this article places the founding of Sierra Leone in that broader, often forgotten context, considering alternatives and paths not taken, as well as exploring some of the reasons why the risky Africa project went forward.

Sierra Leone was one of several experiments in freedom projected or designed in the optimistic mid-1780s. It bears comparison to two in particular, Thomas Jefferson’s plan for ending slavery in ![]() Virginia and the Marquis de Lafayette’s experiment in free black labor in

Virginia and the Marquis de Lafayette’s experiment in free black labor in ![]() French Guiana. In an appendix to his Notes on the State of Virginia (1785), Jefferson proposed that beginning in the year 1800, the children of slaves would go through an apprenticeship training period, followed by emancipation. This was a potentially far-reaching proposal, since half of the enslaved persons in the

French Guiana. In an appendix to his Notes on the State of Virginia (1785), Jefferson proposed that beginning in the year 1800, the children of slaves would go through an apprenticeship training period, followed by emancipation. This was a potentially far-reaching proposal, since half of the enslaved persons in the ![]() United States at this time resided in Virginia. Anticipating social upheaval, Jefferson added that the freed blacks would have to leave the state. He could imagine a free community flourishing in some remote location, such as the western fringes of North America, but not a situation in which former slaveholders and former slaves might meet as equals in the street (Miller 22). Jefferson’s plan was not implemented; large elements of Virginia’s enslaved population did move west in the early nineteenth century, but that involuntary migration would be to newly founded slave states such as

United States at this time resided in Virginia. Anticipating social upheaval, Jefferson added that the freed blacks would have to leave the state. He could imagine a free community flourishing in some remote location, such as the western fringes of North America, but not a situation in which former slaveholders and former slaves might meet as equals in the street (Miller 22). Jefferson’s plan was not implemented; large elements of Virginia’s enslaved population did move west in the early nineteenth century, but that involuntary migration would be to newly founded slave states such as ![]() Alabama and

Alabama and ![]() Mississippi, rather than to a remote province of freedom.

Mississippi, rather than to a remote province of freedom.

Jefferson was not unique in his apprehension about the character of post-emancipation societies; responding to this fear, advocates of gradual abolition seized upon the possibility that a successful pilot project, even a very small one, might sway the skeptics who argued that doing away with slavery would inevitably mean an end to profitable tropical crops such as sugar. In December 1785, with a private blessing from Louis XVI, Lafayette purchased a clove plantation in French Guiana, near ![]() Cayenne, and freed the slaves there. Adrienne, Mme. de Lafayette, took responsibility for much of the work involved in corresponding with the plantation administrators and attending to the religious instruction of the workers. In contrast to Jefferson’s plan for expelling former slaves and leaving them to sort out their own fate, the Lafayette scheme envisaged a sort of enlightened managerial despotism in which failure would not be an option. Revolution in

Cayenne, and freed the slaves there. Adrienne, Mme. de Lafayette, took responsibility for much of the work involved in corresponding with the plantation administrators and attending to the religious instruction of the workers. In contrast to Jefferson’s plan for expelling former slaves and leaving them to sort out their own fate, the Lafayette scheme envisaged a sort of enlightened managerial despotism in which failure would not be an option. Revolution in ![]() Paris and in

Paris and in ![]() Saint-Domingue almost immediately changed the terms of the debate, although truly self-governing free black settlements would remain controversial.

Saint-Domingue almost immediately changed the terms of the debate, although truly self-governing free black settlements would remain controversial.

Given that slavery’s apologists remained vigilant, aggressive, and influential, any experiment in free black labor—even one as paternalist as Lafayette’s—ran the risk of supplying deadly ammunition to those who wished to dismiss all emancipation as ill-informed folly. In this context, Sierra Leone represented extraordinary risks for the antislavery movement. Why situate a fragile new province of freedom in West Africa, an area infested with slave traders who despised abolitionist ideologies and might actually re-enslave the settlers as soon as the British warships departed? Proposals to send large numbers of white convicts to Britain’s small coastal outposts in West Africa had foundered on the strenuous objections of white slave traders who believed that seeing degraded felons doing manual labor would dissipate the “awe” in which Africans held white skin. “Good Heavens, Gentlemen,” wrote one official of the African Company, “only consider Women of our own colour landed here to become common prostitutes among the blacks” (Christopher, “Disgrace”).

The vigilance of the slave traders about developments in their sphere of influence could have served as a reminder that this region was hardly a blank slate; unless armed to the teeth, the province of freedom would owe its survival to the toleration of entrenched polities such as the Temne and the Mende. Why risk attacks from powerful neighbors by locating on the mainland of a continent when a small island would have been easier to defend? The armchair daydreaming of the 1780s about experiments in labor, land use, and good governance flourished in the absence of detailed information about conditions on the ground in West Africa.

John Fothergill, the Quaker physician and botanist, published a proposal in the Gentleman’s Magazine in 1780 arguing for a sugar-cane plantation based upon free labor (“the natives would be employed as servants for hire”) located in the very region where the slave trade was most active (Lettsom xxxiii). This scheme avoided the difficulties involved with coaxing or compelling existing slave owners to surrender their property, and in contrast to Lafayette’s free-labor plantation, it promised to attack the problem at its source by gradually diversifying the African economy away from the slave trade. The young naturalist Henry Smeathman returned from Sierra Leone enthusiastic about his patron’s Fothergill’s plan for “African liberty,” although he seems to have been more excited about enriching himself, or making history as a new “Romulus, or Mahomed,” than a consistent foe of slavery (Pettigrew 275-6). He marveled at his pacifist Quaker backers’ naïve proposal to ban weapons in a settlement located amidst heavily armed neighbors. Smeathman returned to Britain just as an influx of indigent loyalist refugees from the American war raised new possibilities about who might populate such a settlement.

The decisive organizing force that would ultimately carry out the Sierra Leone project would be neither Fothergill nor Smeathman, but a charitable group, the Committee for the Relief of the Black Poor. Significantly, although some of its influential members opposed slavery, the Committee did not originate as part of an antislavery agenda. Rather, it was an emergency effort mobilized to address the suffering of the homeless during a spate of subfreezing temperatures in January 1786. The original “Black Poor” were lascar seamen that had arrived on the ships of the East India Company, but recently arrived African-Americans sought out the Committee’s aid in far greater numbers. Many of these individuals, like the lascars, followed maritime occupations. Of the 250 people who applied for the Committee’s aid early on, 100 stated that they had served as seamen in the Royal Navy. Of the eight Corporals selected by the Committee to represent the Black Poor and serve as intermediaries in deliberations about what steps to take next, three had come to Britain in the Royal Navy and two others had worked as ship’s stewards (Braidwood 27, 63, 70; Committee). Thus, many of the recipients of the Committee’s aid were experienced seafaring men who had already served the empire.

This attention to indigent seafarers coincided with a visit to London in March by John Knox, who was promoting his project to create forty new fishing villages spaced at intervals of twenty-five miles along the thinly populated coast of northern ![]() Scotland. Knox justified his plan in various ways, but his main emphasis was on boosting the number of experienced seafaring men who would be available at the outbreak of any future war with

Scotland. Knox justified his plan in various ways, but his main emphasis was on boosting the number of experienced seafaring men who would be available at the outbreak of any future war with ![]() France. It was thought to take seven years to fully train a sailor, so hasty and indiscriminate conscription was not a satisfactory solution. Knox had a solution for out-of-luck sailors; he wanted to foster what was known as Britain’s “nursery of seamen,” and he argued forcefully that “home colonization” would be the way to do it; distant settlements were hard to defend and would not furnish sailors to defend Britain’s home waters in a hurry (Knox 3, 6). A newly-formed private joint-stock company, the British Fisheries Society, began purchasing land for the proposed villages. The project would receive technical advice from Thomas Telford, one of the great civil engineers of the era, and the planned communities of

France. It was thought to take seven years to fully train a sailor, so hasty and indiscriminate conscription was not a satisfactory solution. Knox had a solution for out-of-luck sailors; he wanted to foster what was known as Britain’s “nursery of seamen,” and he argued forcefully that “home colonization” would be the way to do it; distant settlements were hard to defend and would not furnish sailors to defend Britain’s home waters in a hurry (Knox 3, 6). A newly-formed private joint-stock company, the British Fisheries Society, began purchasing land for the proposed villages. The project would receive technical advice from Thomas Telford, one of the great civil engineers of the era, and the planned communities of ![]() Ullapool and

Ullapool and ![]() Tobermory were established two years later (Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, s.v. John Knox, Thomas Telford; Britannica 3rd ed., (1797), s.v. Fishery).

Tobermory were established two years later (Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, s.v. John Knox, Thomas Telford; Britannica 3rd ed., (1797), s.v. Fishery).

Why did no one propose collaboration between one charitable project, which sought to provide emergency food and shelter for a group that included many indigent seafarers, and another, which planned to build homes for them, and a stable future that would simultaneously enhance Britain’s defenses? The two projects received simultaneous attention from Parliament and in the newspapers. However, the Committee for the Relief of the Black Poor would engage in correspondence with shipping companies about many destinations, but not about Scotland. This is striking for a number of reasons. An influential member of the Committee, Jonas Hanway, had risen to prominence as the founder of the Marine Society, which shared Knox’s focus on the problem of supplying the Navy with experienced sailors, yet the Committee’s own name and concept were not occupational; rather, its purview was limited by a color designation. It seems black veterans elicited a different philanthropic response than white veterans. P. J. Marshall has written that “The treatment of the black loyalists showed that British freedom, albeit in their case in what proved to be a restricted sense, could be transferred to people within the empire who were manifestly not of British origin.” (Marshall 53). Such statements obscure the fact that the “people within the empire,” in the case of the Black Poor, resided in London, and could have enjoyed British freedom without sailing to Africa. Furthermore, a detailed, feasible road map to achieve that end was well-publicized and on its way to reality.

Free blacks in Scotland, of course, could not have grown sugar cane; the antislavery movement would have been denied its tropical experiment. However, a tropical location did not necessarily dictate an African one. The British government showed great interest in occupying small, strategically placed tropical islands in the 1780s, particularly in the Indian Ocean area. To counter the French base at ![]() Mauritius, the East India Company acquired

Mauritius, the East India Company acquired ![]() Diego Garcia in 1785. The

Diego Garcia in 1785. The ![]() Andaman and

Andaman and ![]() Nicobar Islands in the

Nicobar Islands in the ![]() Bay of Bengal attracted attention for their excellent natural harbors.

Bay of Bengal attracted attention for their excellent natural harbors. ![]() Penang (Prince of Wales Island) dominated the important

Penang (Prince of Wales Island) dominated the important ![]() Strait of Malacca and promised to become an imperial possession of the highest commercial and military importance. It became part of the British Empire on 11 August 1786, during the summer when Smeathman’s death threw the Black Poor’s destination back into question (Fry; Frost). A tropical island (particularly one furnished with batteries of artillery) could have offered both a natural fortress and a location in which the free blacks, if persuaded to grow cash crops, could supply evidence against the pessimists in the emancipation debate. A curiosity about alternate destinations may explain why the only surviving copy of Sir George Young’s third

Strait of Malacca and promised to become an imperial possession of the highest commercial and military importance. It became part of the British Empire on 11 August 1786, during the summer when Smeathman’s death threw the Black Poor’s destination back into question (Fry; Frost). A tropical island (particularly one furnished with batteries of artillery) could have offered both a natural fortress and a location in which the free blacks, if persuaded to grow cash crops, could supply evidence against the pessimists in the emancipation debate. A curiosity about alternate destinations may explain why the only surviving copy of Sir George Young’s third ![]() Botany Bay proposal was found among Granville Sharp’s papers (Atkinson 194). It was not to be, although the First Fleet set out for Botany Bay at almost the same time as the Black Poor were launched on their voyage to Sierra Leone, and the naval planners for both expeditions—Sir Charles Middleton and George Rose—were the same. Some of the Black Poor actually disembarked before their ships departed, believing the rumors that the “Province of Freedom” would be nothing but a convict colony.

Botany Bay proposal was found among Granville Sharp’s papers (Atkinson 194). It was not to be, although the First Fleet set out for Botany Bay at almost the same time as the Black Poor were launched on their voyage to Sierra Leone, and the naval planners for both expeditions—Sir Charles Middleton and George Rose—were the same. Some of the Black Poor actually disembarked before their ships departed, believing the rumors that the “Province of Freedom” would be nothing but a convict colony.

The cold calculations of imperial geopolitics might have dictated a different location, but Sierra Leone seemed eminently sensible to those who believed that the British Empire only existed in order to fulfill Old Testament prophecies. The evangelical philanthropist Granville Sharp is remembered today exclusively for his anti-slavery efforts and his extensive involvement with the Sierra Leone project, but significantly, he also helped to found the British and Foreign Bible Society, the Protestant Union (an anti-Catholic organization), and the Society for the Conversion of the Jews. Contemporaries remarked on his habit of dropping unexpected references to Biblical prophecies into everyday conversation about current events (Hoare). Many evangelicals believed that references to “the north country” and “the ships of Tarshish” (Isaiah 11:12; Isaiah 18:1-2; Isaiah 60:9-11; Jeremiah 31:7-8; Jeremiah 31:10) foretold the redemptive role of the Royal Navy, a new global force which had the power to effect the Jews’ return to their ancestral homeland (Bar-Eitan). If Britain’s destiny was to gather up Jewish exiles and bring about the Second Coming, then a parallel suggested itself: British vessels carrying liberated former slaves “back” to West Africa offered a particularly neat reversal of the barbarities of the Middle Passage. Thus, Sharp was disposed to read African bodies, like Jewish bodies, as out of place and in need of transportation. Helping the exiles return to their ancestral point of origin, now supposedly depopulated and unproductive as the result of ancient evils, would also accomplish—in each case—a fitting expiation for Europe’s sins. Divine providence would look kindly upon any project so elegantly conceived as a way to settle accounts with the past.

The choice of West Africa as a destination seems to have taken hold, and persisted, as a result of a dialogue between Granville Sharp and the representatives of the Black Poor themselves. It is impossible to reconstruct these conversations, which are preserved only in Sharp’s own laconic summaries. One voice that does survive from a prospective settler is Olaudah Equiano’s Interesting Narrative. By his own admission, Equiano experimented with many different identities, for example relishing the sense of belonging that he had experienced as a sailor in the Royal Navy. Before he became an advocate of the back-to-Africa project, Equiano showed a great attachment to London. Since his first encounter with that city as a boy in 1757, the longest consecutive period that he spent away from it was the five years between 1762 and 1767—and this was an involuntary exile back to slavery in the Caribbean. He could have used his freedom as a sailor to travel almost anywhere, but 1786 marked the eleventh occasion on which Equiano returned to London after time spent overseas. (The other returns to London noted in the Interesting Narrative were in 1759, 1762, 1767, 1770, 1772, 1773, 1774, 1775, 1777, and 1785.) As Vincent Carretta has observed, among slave narratives, one of the most novel features of Equiano’s book was its treatment of British identity: “He can, of course, never be English, in the ethnic sense in which that word was used during the period, as his wife is English. But he adopts the cultural, political, religious, and social values that enable him to be accepted as British”(Equiano xviii).

Yet by the time that he composed his Interesting Narrative, Equiano had become convinced that the Sierra Leone project, for all its failings, represented the best choice for African-descended people in the diaspora. Although he personally was ill-treated and actually thrown off the transport before it left Britain, he left money in his will for a school in Sierra Leone, and characterized the project itself favorably in his writings (Carretta 365). In the Interesting Narrative, Equiano equated his people with the Jews quite explicitly, citing similarities in the rituals and celebrations, and proposing that the two groups must be related, as if he were descended from a lost tribe of ![]() Israel that had wandered to West Africa (Equiano 41, 43). As Adam Potkay has suggested, the Interesting Narrative mirrors the structure of the Bible, beginning with the simple “pastoral” peoples of Genesis, suffering under outrage and enslavement, and finally progressing to the forgiving spirit of the New Testament; foregoing the temptation of a bloody revenge for enslavement earns one the right to a New Jerusalem in Africa. Equiano could easily have omitted most of the details revealing his affection for London; instead, he included them as markers of an immature stage in his spiritual development. Those who love

Israel that had wandered to West Africa (Equiano 41, 43). As Adam Potkay has suggested, the Interesting Narrative mirrors the structure of the Bible, beginning with the simple “pastoral” peoples of Genesis, suffering under outrage and enslavement, and finally progressing to the forgiving spirit of the New Testament; foregoing the temptation of a bloody revenge for enslavement earns one the right to a New Jerusalem in Africa. Equiano could easily have omitted most of the details revealing his affection for London; instead, he included them as markers of an immature stage in his spiritual development. Those who love ![]() Egypt, Babylon, or London too much would never move on to fulfill their individual or collective destiny.

Egypt, Babylon, or London too much would never move on to fulfill their individual or collective destiny.

This suggests a philosophy of history that was cyclical and redemptive, rather than linear and progressing towards novelty. The projected settlements in ![]() Palestine and West Africa would not be new Englands inscribed on a tabula rasa; rather, they were each a unique remedy for a land that had seen too much history. Settling the Black Poor somewhere other than Africa would have lacked symmetry and failed to provide the kind of redemptive closure that Sharp, Equiano, and their confederates sought. Yet for Britain’s free black population, many possibilities existed other than a Return to a place where most of them had never lived. In fact, only about one third of those who had received aid from the Committee ultimately chose to board the transports for Africa; it seems that the rest (approximately six hundred people) did not consider themselves particularly out of place or in need of repatriation (Land 102).

Palestine and West Africa would not be new Englands inscribed on a tabula rasa; rather, they were each a unique remedy for a land that had seen too much history. Settling the Black Poor somewhere other than Africa would have lacked symmetry and failed to provide the kind of redemptive closure that Sharp, Equiano, and their confederates sought. Yet for Britain’s free black population, many possibilities existed other than a Return to a place where most of them had never lived. In fact, only about one third of those who had received aid from the Committee ultimately chose to board the transports for Africa; it seems that the rest (approximately six hundred people) did not consider themselves particularly out of place or in need of repatriation (Land 102).

Sierra Leone proved unexpectedly attractive to another constituency. About one hundred London women voluntarily embarked; although Equiano took pains to note that they came as wives, as white women consorting with black men they drew derision then, and later, as presumed prostitutes. Europeans had ample reason to believe that even a brief visit to the African tropics might be fatal for them. This does raise interesting questions about why white women were permitted to accompany the Black Poor at all. Given the concerns already raised by white slave traders, it is surprising that the British government would contemplate turning these women adrift in an uncertain African setting where they might become an embarrassment. Alternately, to the extent that the new settlement was intended as a humanitarian venture, sending these women to almost certain death from disease seems incongruous. Anna Maria Falconbridge, who met some of the surviving women a few years later, was told they had been plied with liquor and “inveigled” on board, amounting to “a Gothic infringement on human Liberty” (Falconbridge 70). There is certainly room for further research on this topic, although the event drew so little comment at the time that evidence is scarce. Richard Phillips offers one provocative interpretation, suggesting that “white people were not only medically, but, more fundamentally, racially vulnerable” in the African tropics (Phillips 194). He cites Falconbridge, who described the women as scantily clad and “so disguised with filth and dirt, that I should never have supposed they were born white” (Falconbridge 70). If climate and circumstances had such a transformative impact as to dissolve whiteness, then the anomaly of white women in the tropics would resolve itself in short order. Alternately, perhaps the act of marriage itself, through a kind of coverture, was taken to have severed the women’s ties to their country of origin and joined their destiny to that of the black migrants.

In part because of this complexity and ambiguity, the founding of Sierra Leone has resisted incorporation into larger narratives. Clearly, assessing Sierra Leone’s meaning and legacies depends on what sort of timeline one chooses to create. T. C. McCaskie, writing in the Oxford History of the British Empire, characterized Granville Sharp’s original vision for the settlement as “a donation from the morally enlightened to the spiritually impoverished” and noted an irony: “Britain’s attempt to improve Africa had as its foundational act the first instance, in West Africa, in which sovereign rather than tenant rights were transferred by treaty” (McCaskie 667). Meanwhile, in the UNESCO General History of Africa, the ![]() Ghana-based scholar A. A. Boahen argued that nineteenth-century Freetown offered a liberated space where Africans could control their own Christian churches and the diverse residents, whether migrant, indigenous, or recaptive, could forge their own syncretic culture that was neither entirely European, nor American, nor African. From the viewpoint of the new settlement’s African neighbors, however, Freetown would remain a peripheral development in an increasingly Islamic region—one of the first messages it received from a local ruler was a piece of Arabic calligraphy reproducing a passage from the Koran—and one ruler of a local polity, Naimbana, left himself plenty of room to maneuver by educating “one son locally as a Muslim, sending a second abroad to France, and a third, John Frederic, to London” (Northrup 51).

Ghana-based scholar A. A. Boahen argued that nineteenth-century Freetown offered a liberated space where Africans could control their own Christian churches and the diverse residents, whether migrant, indigenous, or recaptive, could forge their own syncretic culture that was neither entirely European, nor American, nor African. From the viewpoint of the new settlement’s African neighbors, however, Freetown would remain a peripheral development in an increasingly Islamic region—one of the first messages it received from a local ruler was a piece of Arabic calligraphy reproducing a passage from the Koran—and one ruler of a local polity, Naimbana, left himself plenty of room to maneuver by educating “one son locally as a Muslim, sending a second abroad to France, and a third, John Frederic, to London” (Northrup 51).

Intent on salvaging what had been, in its first few years, an embarrassing failure, the Sierra Leone Company adopted a paternalist approach more in keeping with Lafayette’s managerial despotism. One governor even changed the name “Freetown” to “Georgetown” for a time, seeking to eliminate anything that smacked of republicanism (Fyfe 107). The black loyalists from Nova Scotia appeared, at first, as a valuable counterbalance to the restive survivors of the first settlement, yet in a few years their Volunteer Corps would be disbanded and the Maroons, “less infected by democratic insolence” (Fyfe 107) would take their place in the new militia. The Trelawney Maroons had a complex history, having fought the British to a draw in ![]() Jamaica and earned a treaty allowing them autonomy in the interior in return for serving as slave-catchers. The Haitian Revolution destabilized old arrangements and a fresh rebellion resulted in their expulsion to Nova Scotia. The Maroons understood themselves as a group with a distinct history, and an identity different both from the slave owners and from Jamaica’s enslaved population (Wilson). Once in Sierra Leone, they proudly set about hunting the “rascals” who were not properly loyal to King George. Migration to Africa appeared to offer them an opportunity to “return to their place in between black and white society, once again policing other blacks in the British Atlantic World” (Fortin 20). It would only be a matter of time, however, before the Maroons, too, became a thorn in the side of the British authorities.

Jamaica and earned a treaty allowing them autonomy in the interior in return for serving as slave-catchers. The Haitian Revolution destabilized old arrangements and a fresh rebellion resulted in their expulsion to Nova Scotia. The Maroons understood themselves as a group with a distinct history, and an identity different both from the slave owners and from Jamaica’s enslaved population (Wilson). Once in Sierra Leone, they proudly set about hunting the “rascals” who were not properly loyal to King George. Migration to Africa appeared to offer them an opportunity to “return to their place in between black and white society, once again policing other blacks in the British Atlantic World” (Fortin 20). It would only be a matter of time, however, before the Maroons, too, became a thorn in the side of the British authorities.

Accepting waves of rebels was proving a shaky foundation for building a new, stable colony. In 1802, Thomas Jefferson, now President of the United States, asked his Ambassador to the Court of St. James, Rufus King, to approach Wilberforce and Thornton about taking the rebel slaves implicated in Gabriel’s Rebellion. Jefferson hoped that this would be the first step toward sending large numbers of African-Americans to Africa, but he met with a curt refusal. As Jefferson summarized the reply: “in no event should they be willing to receive more of these people from the United States, as it was that portion of settlers. . . who, by their idleness and turbulence, had kept the settlement in constant danger of dissolution” (American Colonization Society 7). Thus, while the colony had been founded by white and black abolitionists, rebels against slavery were now seen as ungovernable. The Sierra Leone project had been marked by ambivalence from the beginning; now, it shut off a plausible source of fresh settlers without identifying a new one.

The recaptives would form the largest demographic input into nineteenth-century Sierra Leone. Hailing from other parts of Africa, they fulfilled the redemptive fantasy of slave ships checked and set on a return course. They were also thought to lack the fluency to lodge articulate claims in the name of British freedom. Indeed, recaptives were soon deployed as soldiers against the insubordinate Maroons. Large numbers of Maroons were outlawed and lost their property; most of the survivors returned to Jamaica in 1841 (Fyfe 119; Fortin 23).

Most abolitionists had envisioned Sierra Leone as a plantation colony, differing only in the absence of slavery. Paul Cuffe, the black New England merchant and sea captain, planned a very different future for West Africa. On 1 August 1811, Cuffe’s brig Traveller arrived at ![]() Liverpool from Sierra Leone. The Times reported with some wonderment that this ship was “perhaps the first vessel that ever reached Europe, entirely owned and navigated by Negroes.” For incredulous readers, the newspaper elaborated: “Her mate, and all her crew, are negroes, or the immediate descendants of negroes” (2 August 1811). The Edinburgh Review relished the moment: “it must have been a strange and animating spectacle to see this free and enlightened African entering as an independent trader, with his black crew, into that port which was so lately the nidus of the slave trade” (18:36 [August 1811], 321). The enslaved status of Captain Cuffe’s father drew specific attention in both publications; thus not only Cuffe’s ethnicity, but his immediate descent from slaves, made this a significant moment. People lined the shore to witness this novelty (Thomas 57).

Liverpool from Sierra Leone. The Times reported with some wonderment that this ship was “perhaps the first vessel that ever reached Europe, entirely owned and navigated by Negroes.” For incredulous readers, the newspaper elaborated: “Her mate, and all her crew, are negroes, or the immediate descendants of negroes” (2 August 1811). The Edinburgh Review relished the moment: “it must have been a strange and animating spectacle to see this free and enlightened African entering as an independent trader, with his black crew, into that port which was so lately the nidus of the slave trade” (18:36 [August 1811], 321). The enslaved status of Captain Cuffe’s father drew specific attention in both publications; thus not only Cuffe’s ethnicity, but his immediate descent from slaves, made this a significant moment. People lined the shore to witness this novelty (Thomas 57).

Cuffe’s plan was to make such voyages, such captains, and such crews quite routine. He thought Freetown could flourish as a whaling port, with a diversified economy similar to ![]() Massachusetts or

Massachusetts or ![]() Rhode Island. A prosperous and self-sufficient community of black investors would build ships, import machinery such as sawmills and rice mills, and patronize a class of black artisans and mechanics (Cuffe, Brief Account). He saw these developments as the necessary corollary of self-rule: “African Americans should strive to place our children in the contry of their origian upon a level with our neighbours the white Brother (Viz). They become their national Representatives their merchants and their navigators and Becoming a national body” (Cuffe, Logs and Letters 271).

Rhode Island. A prosperous and self-sufficient community of black investors would build ships, import machinery such as sawmills and rice mills, and patronize a class of black artisans and mechanics (Cuffe, Brief Account). He saw these developments as the necessary corollary of self-rule: “African Americans should strive to place our children in the contry of their origian upon a level with our neighbours the white Brother (Viz). They become their national Representatives their merchants and their navigators and Becoming a national body” (Cuffe, Logs and Letters 271).

He would be appalled to learn how the monopolies enjoyed by white merchants stifled the settlers’ entrepreneurial instincts. He found agriculture, also, in a somnolent state; the black settlers were not encouraged to raise “any more than to sustain their wants.” Meanwhile, the young men left to become sailors “on board foreigners,” robbing Sierra Leone of some of its more enterprising people. This only underscored the need for Freetown residents to become “their own shippers and importers,” but Cuffe’s own efforts to trade with the colony were impeded by the white monopolists and by the troubled relations between the United States and Great Britain that would culminate in the War of 1812 (Cuffe, Logs and Letters 177, 119, 342).

Cuffe’s plans, and their frustration, remind us that while Sierra Leone belongs on a timeline of great Atlantic revolutions, it was also a troubled post-emancipation society, where conflict raged over what “freedom” meant. Was it the mere removal of enslavement, or did emancipation require meaningful economic and political self-determination as well as social equality? Alexander X. Byrd has drawn attention to the deliberate actions taken by slave traders to undermine and nearly destroy the settlement in its infancy. As with the rebellious French Caribbean colony of Saint-Domingue in this same period, with a variety of economic and ideological interests ranged against it on a hemispheric or even global scale, consolidating “the revolution in one country” would prove almost prohibitively difficult.

Freetown may have been conceived as a great exception to imperialism, or a backpedaling that would actually reverse some of imperialism’s worst legacies, yet imperialism persisted all around it and sought to pass its own verdict on the bold experiment. By the late nineteenth century, there was an established protocol for describing Freetown. It was laughable, chaotic, miasmatic, ugly, a dystopian parody of its naïve visionary beginnings (Phillips). Tropical spaces, set apart by their “white man’s grave” reputation, also uniquely called for the white man’s presence; only oversight and intervention could correct natural and moral disorder on such a scale (Arnold). The tropicalization of Freetown began early. A street settled by Nova Scotians was dubbed “Discontented Row” (Fyfe 99). Of course, reporting that the settlers were ungrateful, unruly, and demanding was also a grudging admission that they believed themselves fully capable and deserving of self-government.

In the end, it proved impossible to present freedom as a gift to people who had already liberated themselves, often at great personal risk. London’s Black Poor, the Nova Scotians, and the Maroons each saw themselves as a self-governing group, even when it was necessary to cooperate with projectors, ship captains, and appointed governors. One admiring outsider remarked, “Never did [an] ambassador from a sovereign power prosecute with more zeal the object of his mission than did Thomas Peters the cause of his distressed countrymen” (Byrd 181). Through debates, formal votes, and of course the exercise of choice when it came to embarking on voluntary migrations, Sierra Leone fulfilled its promise as “the Province of Freedom” even before landfall in Africa. Cuffe spelled out precisely what was at stake when he expressed the hope that in Sierra Leone, former slaves would “become mannegers of themselves” and their descendants emerge as “a Nation to be Numbered among the historians nations of the World.” (Cuffe, Logs and Letters 119)

published December 2013

HOW TO CITE THIS BRANCH ENTRY (MLA format)

Land, Isaac. “On the Foundings of Sierra Leone, 1787-1808.” BRANCH: Britain, Representation and Nineteenth-Century History. Ed. Dino Franco Felluga. Extension of Romanticism and Victorianism on the Net. Web. [Here, add your last date of access to BRANCH].

WORKS CITED

American Colonization Society. The Annual Reports of the American Society for Colonizing the Free People of Colour of the United States, vol. 1 (1818), facsimile reprint. New York: Negro U P, 1969. Print.

Arnold, David. The Tropics and the Traveling Gaze: India, Landscape, and Science, 1800-1856. Seattle: U of Washington P, 2006. Print.

Atkinson, Alan. “Whigs and Tories and Botany Bay.” The Founding of Australia: The Argument about Australia’s Origins. Ed. Ged Martin. 186-209. Sydney: Hale and Iremonger, 1978. Print.

Bar-Yosef, Eitan. The Holy Land in English Culture, 1799-1917: Palestine and the Question of Orientalism. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 2005. Print.

Braidwood, Stephen J. Black Poor and White Philanthropists: London’s Blacks and the Foundation of the Sierra Leone Settlement, 1786-1791. Liverpool: Liverpool UP, 1994. Print.

Boahen, A. A. “New Trends and Processes in Africa in the Nineteenth Century.” Africa in the Nineteenth Century until the 1880s. Ed. J. F. Ade Ajayi. 40-63. Paris: UNESCO, 1989. Print.

Brown, Christopher Leslie. Moral Capital: Foundations of British Abolitionism. Chapel Hill: U of North Carolina P, 2006. Print.

Byrd, Alexander X. Captives and Voyagers: Black Migrants across the Eighteenth-Century British Atlantic World. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State UP, 2008. Print.

Carretta, Vincent. Equiano the African: Biography of a Self-Made Man. Athens, GA: U of Georgia P, 2005. Print.

Christopher, Emma. “A ‘Disgrace to the Very Colour’: Perceptions of Blackness and Whiteness in the Founding of Sierra Leone and Botany Bay.” Journal of Colonialism and Colonial History 9.3 (Winter 2008). Project MUSE. Web. 30 July 2012.

—. A Merciless Place: The Fate of Britain’s Convicts after the American Revolution. Oxford: Oxford UP, 2010. Print.

Coleman, Deirdre. Romantic Colonization and British Anti-Slavery. Cambridge: Cambridge UP, 2005. Print.

Committee for the Relief of the Black Poor. The National Archives (Kew) T 1/632, Minutes of June 7, 1786.

Cugoano, Quobna Ottobah. Thoughts and Sentiments on the Evil of Slavery and Other Writings. Ed. Vincent Carretta. New York: Penguin, 1999. Print.

Cuffe,Paul. A Brief Account of the Settlement and Present Situation of the Colony of Sierra Leone. New York: Wood, 1812. Print.

—. Captain Paul Cuffe’s Logs and Letters, 1808-1817: A Black Quaker’s “Voice from within the Veil”. Washington, DC: Howard UP, 1996. Print.

Equiano, Olaudah. The Interesting Narrative and Other Writings. Ed. Vincent Carretta. New York: Penguin, 2003. Print.

Falconbridge, Anna Maria. “Two Voyages to Sierra Leone.” Maiden Voyages and Infant Colonies: Two Women’s Travel Narratives of the 1790s. Ed. Deirdre Coleman. London: Leicester UP, 1999. Print.

Fortin, Jeffrey A. “’Blackened Beyond Our Native Hue’: Removal, Identity and the Trelawney Maroons on the Margins of the Atlantic World, 1796-1800.” Citizenship Studies 10.1 (February 2006): 5-34. Print.

Frost, Alan. The Global Reach of Empire: Britain’s Maritime Expansion in the Indian and Pacific Oceans, 1764-1815. Carlton: Miegunyah Press, 2003. Print.

Fry, H. T. “’Cathay and the Way Thither’: The Background to Botany Bay.” The Founding of Australia: The Argument about Australia’s Origins. Ed. Ged Martin. Sydney: Hale and Iremonger, 1978. 136-150. Print.

Fyfe, Christopher. A History of Sierra Leone. Oxford: Oxford UP, 1962. Print.

Hoare, Prince. Memoirs of Granville Sharp. London: Henry Colburn, 1820. Print.

Jasanoff, Maya. Liberty’s Exiles: American Loyalists in the Revolutionary World. New York: Knopf, 2011. Print.

Knox, John. Observations on the Northern Fisheries. London: J. Water, 1786. Print.

Land, Isaac. “Bread and Arsenic: Citizenship from the Bottom Up in Georgian London.” Journal of Social History 39.1 (Fall 2005): 89-110. Print.

Land, Isaac and Andrew Schocket. “New Approaches to the Founding of the Sierra Leone Colony, 1786-1808.” Journal of Colonialism and Colonial History 9.3 (Winter 2008). Project MUSE. Web. 5 July 2012.

Lettsom, John Coakley. The Works of John Fothergill. London: Charles Dilly, 1784. Print.

Marshall, P. J. “Empire and British Identity: The Maritime Dimension.” Empire, the Sea, and Global History. Ed. David Cannadine. New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2007.41-59. Print.

McCaskie, T. C. “Cultural Encounters: Britain and Africa in the Nineteenth Century.” The Oxford History of the British Empire, vol. III, The Nineteenth Century. Ed. Andrew Porter and Alaine Low. Oxford: Oxford UP, 1999. 665-689. Print.

Miller, John Chester. The Wolf by the Ears: Thomas Jefferson and Slavery. New York: Free Press, 1977. Print.

Northrup, David. “West Africans and the Atlantic, 1550-1800.” Black Experience and the Empire. Ed. Philip D. Morgan and Sean Hawkins.Oxford UP, 2004. 35-57. Print.

Pettigrew, Thomas Joseph. Memoirs of the Life and Writings of the Late John Coakley Lettsom. London: Longman, 1817. Print.

Phillips, Richard. “Dystopian Space in Colonial Representations and Interventions: Sierra Leone as the ‘White Man’s Grave.’” Geografiska AnnalerSeries B, Human Geography 84.3/4 (2002): 189-200. Print.

Potkay, Adam. “Olaudah Equiano and the Art of Spiritual Autobiography.” Eighteenth-Century Studies 27.4 (Summer 1994): 677-92. Print.

Pybus, Cassandra. Epic Journeys of Freedom: Runaway Slaves of the American Revolution and Their Global Search for Liberty. Boston: Beacon Press, 2006. Print.

Thomas, Lamont D. Rise to be a People: A Biography of Paul Cuffe. Urbana, IL: U of Illinois P, 1986. Print.

Saillant, John. “The American Enlightenment in Africa: Jefferson’s Colonizationism and Black Virginians’ Migration to Liberia, 1776-1840.” Eighteenth-Century Studies 31.3 (1998): 261-282. Print.

Schama, Simon. Rough Crossings: Britain, the Slaves, and the American Revolution. New York: HarperCollins, 2006. Print.

Sweet, James H. “Mistaken Identities? Olaudah Equiano, Domingos Álvares, and the Methodological Challenges of Studying the African Diaspora.” American Historical Review 114.2 (April 2009): 279-306. Print.

Willens, Liliane. “Lafayette’s Emancipation Experiment in French Guiana, 1786-1792.” Studies on Voltaire and the Eighteenth Century 242 (1986): 345-362. Print.

Wilson, Kathleen. “The Performance of Freedom: Maroons and the Colonial Order in Eighteenth-Century Jamaica and the Atlantic Sound.” William and Mary Quarterly 3rdser. 66.1 (January 2009): 45-86. Print.