Abstract

This essay explores the 1886 Colonial and Indian Exhibition, focusing specifically on its unprecedented display of 34 Indian artisans. It contextualizes this display in relation to Victorian discourses that lamented the disappearance of the British working body through mechanization, and that conflated the authenticity of South Asian crafts with the presence of “genuine” Indian bodies.

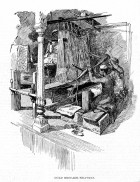

[Illustration 1: “Gold Brocade Weavers.” “Colonial Indian Exhibition: The Indian Empire.” Illustrated London News 17 July 1886: 84. Courtesy of the Bowdoin College Library, Brunswick, Maine]

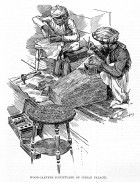

[Illustration 2: “Woodcarvers (Courtyard of Indian Palace).” “Colonial Indian Exhibition: The Indian Empire.” Illustrated London News 17 July 1886: 84. Courtesy of the Bowdoin College Library, Brunswick, Maine]

Britain’s myriad voices call,

‘Sons, be welded each and all

Into one imperial whole,

One with Britain, heart and soul!

One life, one flag, one fleet, one throne!’

Britons, hold your own![1]

The Colonial and Indian Exhibition opened in ![]() South Kensington on 4 May 1886, lasted over six months, and accommodated 5.5 million visitors (Barringer, “South Kensington” 23). Featuring extravagant displays from British colonial holdings, the exhibit was organized by the Prince of Wales as an “imperial object lesson” in England’s power and grandeur. In the words of an article from the Saturday Review, “Now if any man can look at this and not come away with a new and a lively sense of the greatness of the country he belongs to, he must be a fellow of a very dull imagination and a very stupid temperament” (“Imperial Object” 633). The exhibition was intended to provide ocular proof of the “commercial wealth and power of England beyond the seas” (Peripatetic 511), the “solidarity of a world-wide Empire, its unity of interest, and its manifold resources” (“Colonial and Indian,” Saturday Review). The fact that it was located in South Kensington, an “exhibitionary complex” that, since its establishment in 1857, had become a monument to “Victorian high imperialism” (Kriegel 6), confirmed its dedication to perpetuating the colonial project. The Indian section consisted of the most spectacular and largest of the displays, measuring at five times the size of the Indian Pavilion at the 1851

South Kensington on 4 May 1886, lasted over six months, and accommodated 5.5 million visitors (Barringer, “South Kensington” 23). Featuring extravagant displays from British colonial holdings, the exhibit was organized by the Prince of Wales as an “imperial object lesson” in England’s power and grandeur. In the words of an article from the Saturday Review, “Now if any man can look at this and not come away with a new and a lively sense of the greatness of the country he belongs to, he must be a fellow of a very dull imagination and a very stupid temperament” (“Imperial Object” 633). The exhibition was intended to provide ocular proof of the “commercial wealth and power of England beyond the seas” (Peripatetic 511), the “solidarity of a world-wide Empire, its unity of interest, and its manifold resources” (“Colonial and Indian,” Saturday Review). The fact that it was located in South Kensington, an “exhibitionary complex” that, since its establishment in 1857, had become a monument to “Victorian high imperialism” (Kriegel 6), confirmed its dedication to perpetuating the colonial project. The Indian section consisted of the most spectacular and largest of the displays, measuring at five times the size of the Indian Pavilion at the 1851 ![]() Crystal Palace Exhibition and costing an impressive £22,000 (Mathur 57; Greenhalgh 59). Accessed through the richly sculpted

Crystal Palace Exhibition and costing an impressive £22,000 (Mathur 57; Greenhalgh 59). Accessed through the richly sculpted ![]() Gwalior Gateway, which had been a central component of the 1883 Calcutta International Exposition, it displayed traditional Indian artworks and crafts in fantastic showcases, including an Indian palace and bazaar, as well as the reproduction of a jungle through whose leafy spaces visitors could wander.[2] As the introduction to the Art Journal supplement devoted to the exhibition explained, these Indian displays must “occasion to us and to all true lovers of their country a sense of joy and gratitude for what has been done by these, our far-off children, in the near past, and a glad anticipation of the triumphs in store for them and for us in the not distant future” (2). This undeniably paternalistic rhetoric reflects the sense of colonial proprietorship that pervaded the exhibit, and which justified past and future imperial ventures. The introduction continues: “Our own small and comparatively insignificant island has little room for expansion, except in these broad lands across the sea we have made our own” (2). The exhibit symbolically collapsed the distance between England and its “far-off children” through the inclusion of a display of Indian craftsmen.[3]

Gwalior Gateway, which had been a central component of the 1883 Calcutta International Exposition, it displayed traditional Indian artworks and crafts in fantastic showcases, including an Indian palace and bazaar, as well as the reproduction of a jungle through whose leafy spaces visitors could wander.[2] As the introduction to the Art Journal supplement devoted to the exhibition explained, these Indian displays must “occasion to us and to all true lovers of their country a sense of joy and gratitude for what has been done by these, our far-off children, in the near past, and a glad anticipation of the triumphs in store for them and for us in the not distant future” (2). This undeniably paternalistic rhetoric reflects the sense of colonial proprietorship that pervaded the exhibit, and which justified past and future imperial ventures. The introduction continues: “Our own small and comparatively insignificant island has little room for expansion, except in these broad lands across the sea we have made our own” (2). The exhibit symbolically collapsed the distance between England and its “far-off children” through the inclusion of a display of Indian craftsmen.[3]

Showcasing thirty-four artisans working at a range of crafts, the Indian court was one of the most popular destinations of the 1886 exhibit. In Reminiscences of the Colonial and Indian Exhibition, Frank Cundall writes:

They are genuine artisans, such as may be seen at work within the precincts of the palaces of many of the Indian Princes. . . .Weavers of gold brocade and kinkhab, tapestry and carpets, an ivory miniature painter, copper and silver smiths, a seal engraver, a dyer, a calico printer, a trinket maker, a goldsmith, stone carvers, a clay-figure maker from Lucknow, a potter [who was allegedly 102 years old], and wood carvers, were all daily to be seen at work as they would be in

India. (28-29)

Cundall’s account is typical in stressing the authenticity of these artisans, who were often depicted as un-self-consciously executing the type of work they would otherwise be doing in any given marketplace in India: “Two Punjabi carpenters may be seen hard at work, little heedful of the curious throng which intently watches them” (Banfield 668); “Here are the carpet-weavers, four in number, mingling work and song, their chant barbaric and not without fascination” (“Colonial and Indian,” Saturday Review); “The native artificers, who, in the court of the Indian palace, pursue their various callings in native fashion, are eagerly watched by crowds daily; but they can never be rivalled by English workers, for their work requires not only delicacy of manipulation, but patient labour, only possible in a land where workers are numerous and wages extremely low” (“Colonial and Indian,” Westminster Review 33). T.N. Mukharji, one of the three Indian men commissioned to help organize the exhibition, commented on the wonder produced by these workers: “A dense crowd always stood there, looking at our men as they wove the gold brocade, sang the patterns of the carpet and printed the calico with the hand. They were as much astonished to see the Indians produce works of art with the aid of rude apparatus they themselves had discarded long ago, as a Hindu would be to see a chimpanzee officiating as a priest in a funeral ceremony” (99).[4] The exhibition instilled the fantasy of a privileged, unmediated, and even voyeuristic view of “real” Indian work. Patrons were invited to observe this labor and then purchase samples to take home with them, thereby going on to consume the authenticity on display.

Of course, this presentation of authenticity was staged; the artisans were there to perform labor. Despite the Prince of Wales’s alleged exclamation, “Why you have India itself here!” (qtd. in Spear 916), the exhibit was only a “simulation” (Spear 916). Most of the workers were prisoners from the Central Jail in Agra, where they had been trained in various crafts as part of their rehabilitation. During the course of the exhibit, they labored under the close supervision of Dr. John William Tyler, the superintendent of the prison (Mathur 63-66). The coerced nature of their performance, the fact that the skills they demonstrated were “likely to have been learned through the industrializing processes of prison reform rather than through the ancient, timeless practices of the village” (Mathur 66)—as well as the theatricality of the exhibition as a whole—undermined the authenticity of the display. As Nicky Levell reminds us, “Reconstructed mimetic environments replete with ‘exotic’ life exhibits, were in actuality, occidental imaginaries, idealised visions of the Orient, that had been devised and designed by the West” (70).

To visitors of the 1886 exhibition, however, the mere presence of the workers may have offered a sufficient degree of authenticity. In Julie Codell’s words, “Any Indian hands, even of . . . prisoners, were legitimized under British re-definitions of authenticity and tradition” (160). The artisans’ laboring bodies provided direct evidence of genuine handicrafts of the type that England had supposedly forsaken in its industrial turn. The second half of the nineteenth century witnessed the emergence of an Arts and Crafts discourse that lamented the shift from manual labor to the mechanizations of industry. As John Ruskin famously wrote in “The Nature of Gothic” (1853), “Men were not intended to work with the accuracy of tools, to be precise and perfect in all their actions. If you will have that precision out of them, and make their fingers measure degrees like cog-wheels, and their arms strike curves like compasses, you must unhumanize them” (161). The 1851 ![]() Great Exhibition was instrumental in associating Indian artifacts with the type of ideal craftsmanship that England had supposedly lost to the machine. Prior to the opening of the Crystal Palace, the Illustrated London News enticed its readers with images of Indian craftsmen producing works for the exhibit, and the completed Indian pavilion featured sixty clay figures from Krishnagur representing Indian artisans at work (Kriegel 113, 117). Tim Barringer explains that the resulting admiration for Indian art was “deeply corrosive of widely held mid-Victorian assumptions concerning national and racial superiority, progress, and mechanisation” (Men at Work 260). He goes on to argue that “the process of labour, the handcrafting of the complete object by the skilled and creative individual, provides an alternative, and superior, form of work to that of the division of labour under mechanized industrial capitalism” (Men at Work 261). The fascination with Indian production increased in intensity following the Crystal Palace Exhibition, as evidenced by the South Kensington Museum’s acquisition of the East India Company’s collection of Indian art in 1879 (Kriegel 144) and the inception of the Journal of Indian Arts in 1884 (renamed the Journal of Indian Art and Industry in 1894), which regularly featured images of laboring Indian artisans.[5] One of the most influential treatises on the value of Indian craftsmanship was George Birdwood’s The Industrial Arts of India, which he wrote for the 1878

Great Exhibition was instrumental in associating Indian artifacts with the type of ideal craftsmanship that England had supposedly lost to the machine. Prior to the opening of the Crystal Palace, the Illustrated London News enticed its readers with images of Indian craftsmen producing works for the exhibit, and the completed Indian pavilion featured sixty clay figures from Krishnagur representing Indian artisans at work (Kriegel 113, 117). Tim Barringer explains that the resulting admiration for Indian art was “deeply corrosive of widely held mid-Victorian assumptions concerning national and racial superiority, progress, and mechanisation” (Men at Work 260). He goes on to argue that “the process of labour, the handcrafting of the complete object by the skilled and creative individual, provides an alternative, and superior, form of work to that of the division of labour under mechanized industrial capitalism” (Men at Work 261). The fascination with Indian production increased in intensity following the Crystal Palace Exhibition, as evidenced by the South Kensington Museum’s acquisition of the East India Company’s collection of Indian art in 1879 (Kriegel 144) and the inception of the Journal of Indian Arts in 1884 (renamed the Journal of Indian Art and Industry in 1894), which regularly featured images of laboring Indian artisans.[5] One of the most influential treatises on the value of Indian craftsmanship was George Birdwood’s The Industrial Arts of India, which he wrote for the 1878 ![]() Paris Universal Exhibition and which later served as a handbook for the South Kensington Museum (152). Birdwood contrasted the downfall of Western manual production with the proliferation of Indian artistry:

Paris Universal Exhibition and which later served as a handbook for the South Kensington Museum (152). Birdwood contrasted the downfall of Western manual production with the proliferation of Indian artistry:

The very word manufacture has in Europe come at last to lose well nigh all trace of its true etymological meaning, and is now generally used for the process of the conversion of raw materials into articles suitable for the use of man by machinery. . . . In India everything is hand wrought, and everything, down to the cheapest toy or earthen vessel, is therefore more or less a work of art. (131)

Through its presentation of artisans, the 1886 exhibition conflated the authenticity of “native” crafts with the presence of “genuine” Indian bodies.

Accounts of the display emphasized the humanity of these workers, the fact that they were men rather than machines. In Mathur’s words, “The external features of [the worker’s] body—his dress and adornment, his racial markings, his movements and gestures—were all celebrated as part of an enduring tradition of artisanship that was somehow perfect and historically pure” (58). Articles like Frank Banfield’s in Time emphasized this authenticity by giving readers an “inside” view of the workers’ positions and perspectives. Banfield writes that “The crowd gazing at these silent workers is apt to be misled by their apparent stolidity, and to forget that they are not automatic or clay figures. . . . These Indian artisans are more communicative when their own countrymen are near.” He cites an “Indian gentleman” who interviewed one of the workers: “‘He says that most of the visitors do not see their work, but only look at them and their movements. He also quietly told me that he did not quite like the very audible remarks of some visitors, who seem to look upon them as animals’” (668). While the inclusion of the workers’ perspective may seem discordant in an article that otherwise sensationalizes them, it is emblematic of the particular type of humanization that Banfield and others seek to convey. This humanization resides on a scale of authenticity rather than ethics, focusing less on the fact that these artisans are objectified by visitors than that they are real, human examples of Indian craftsmen. Abigail McGowan unravels the motives behind such displays: “By the end of the century, exhibitions that otherwise reduced cultures to their objects and obscured labor now also tried to offer visual evidence of production. But they did so not out of respect for Indian technologies, but out of a sense that production in India could not be abstracted from the male artisanal body” (61). The laborers’ humanity increases their status as fascinating objects of the gaze and examples of the successes of imperialism: “In conclusion, I may venture to remark that the Indian and Colonial Exhibition is admirably adapted to impress English people with the reality, and the splendour, and magnitude of the inheritance with which our race has been entrusted” (Banfield 672; italics added).

The focus on the authenticity of the Indian worker’s body filled in for the absence of the British laborer from public display. If one of the effects of industrialization was to replace the human body with the machine, the Indian artisan became a prime visual signifier of physical labor (Hoffenberg 184-86; Barringer, Men at Work 248). This “cult of the craftsman” (Mathur 19), which extended well beyond the 1886 exhibition, was inseparable from the colonial project. England’s responsibility was to regulate the work of Indian artisans, who might otherwise misuse their talents. Deepali Dewan argues that “The ‘native craftsman,’ . . . as a symbol of tradition and nonindustrialization, became a site of contention and justification for Empire. He embodied qualities that were, on the one hand, to be praised and, on the other hand, to be condemned, controlled, and improved” (“Scripting” 41). An article on the exhibit from the Westminster Review reflects the need for continued intervention: “This is not the display of an effete nation sunk in Oriental lethargy, with no thought save of luxury and repose, neither is it the tribute of a conquered nation laying its best gifts at the feet of the conqueror, but it is the work of a Power acting the part of a regenerator, guiding the myriad hands in paths of reproductive industry” (35; italics added). If England had lost its hands to the machine—both literally, through the rise in industrial accidents, and metaphorically, through the turn to machine-made art—it had the responsibility to guide the hands of India’s workers. As Arindam Dutta points out, this imperial system of production was at risk of reproducing the distinctly dehumanizing aspects of industrial labor: “The artisan’s customary skills become a cultural analogue of the machine, conceptually blind but corporeally productive. The hand of the traditional artisan is like the glitch in the metallic roller that churns out design in spite of itself” (140). The 1886 exhibition contributed to the necessary illusion that Indian hands were there for the guiding, ready to continue weaving the fabric of the British Empire.

The image of the artisan was as pliable as it was powerful. By 1905, it had been seized by the Bengali swadeshi campaign, which advocated a return to traditional crafts as a resistance to British imperialism. Representations of traditional labor were central to the movement, which “created a new prestige for such indigenous symbols as the handloom, the spinning wheel, and the craftsman himself” (Mathur 43). Mahatma Gandhi later appropriated this image of traditional manual labor in his campaign for Indian independence: “Just as we cannot live without breathing and without eating, so it is impossible for us to attain economic independence and banish pauperism from this ancient land without reviving home-spinning. I hold the spinning wheel to be as much a necessity in every household as the hearth” (297).[6] Jeffrey Spear traces the historical significance of this image to its Arts and Crafts past: “The iconic image of Gandhi with a spinning wheel, which resonated in the West as well as in India, owes at least as much to the efforts of Birdwood, the South Kensington arts administrators, and their successors to promote the village artisan as a signifier of essential India as it does to the fact that Gandhi actually read Ruskin” (917). The adaptability of the artisan image from these seemingly antithetical contexts, shifting form imperialist symbol to liberatory icon, not only attests to its power but to what postcolonial theorists have identified as the mutability of imperial discourse. It is yet another reminder of Sara Suleri’s claim that “colonial facts are vertiginous. . . . They frequently fail to cohere around the master-myth that proclaims static lines of demarcation between imperial power and disempowered culture, between colonizer and colonized” (3).

HOW TO CITE THIS BRANCH ENTRY (MLA format)

published January 2012

Briefel, Aviva. “On the 1886 Colonial and Indian Exhibition.” BRANCH: Britain, Representation and Nineteenth-Century History. Ed. Dino Franco Felluga. Extension of Romanticism and Victorianism on the Net. Web. [Here, add your last date of access to BRANCH].

WORKS CITED

Banfield, Frank. “The Colonial and Indian Exhibition.” Time (Jun. 1886): 662-72. ProQuest. Web. 24 Oct. 2011.

Barringer, Tim. Men at Work: Art and Labour in Victorian Britain. New Haven: Yale UP, 2005. Print.

—. “The South Kensington Museum and the Colonial Project.” Colonialism and the Object: Empire, Material Culture and the Museum. Barringer and Flynn 11-27.

Barringer, Tim and Tom Flynn, eds. Colonialism and the Object: Empire, Material Culture and the Museum. London: Routledge, 1998. Print.

Birdwood, George M. The Industrial Arts of India. 1880. London: Reprint Press, 1971. Print.

Codell, Julie F. “Indian Crafts and Imperial Policy: Hybridity, Purification, and Imperial Subjectivities.” Material Cultures, 1740-1920: The Meanings and Pleasures of Collecting. Ed. John Potvin and Alla Myzelev. Surrey: Ashgate, 2009. 149-70. Print.

“The Colonial and Indian Exhibition.” Art Journal (Dec. 1886): Supplemental section (1-32). Print.

“The Colonial and Indian Exhibition.” Saturday Review 22 May 1886: 707. ProQuest. Web. 24 Oct. 2011.

“The Colonial and Indian Exhibition.” Westminster Review 70 (July 1886): 29-59. ProQuest. Web. 24 Oct. 2011.

“Colonial Indian Exhibition: The Indian Empire.” Illustrated London News 17 July 1886: 84. ProQuest. Web. 24 Oct. 2011.

Cundall, Frank, ed. Reminiscences of the Colonial and Indian Exhibition. London: William Clowes, 1886. Google Book Search. Web. 24 Oct. 2011.

Dewan, Deepali. “The Body at Work: Colonial Art Education and the Figure of the ‘Native Craftsman.’” Confronting the Body: The Politics of Physicality in Colonial and Post-Colonial India. Ed. James H. Mills and Satadru Sen. London: Anthem Press, 2004. 118-34. Print.

—. “Scripting South Asia’s Visual Past: The Journal of Indian Art and Industry and the Production of Knowledge in the Late Nineteenth Century.” Imperial Co-Histories: National Identities and the British and Colonial Press. Ed. Julie F. Codell. Madison: Fairleigh Dickinson UP, 2003. 29-44. Print.

Dutta, Arindam. The Bureaucracy of Beauty: Design in the Age of its Global Reproducibility. New York: Routledge, 2007. Print.

Gandhi, Mahatma. “The Duty of Spinning.” 1921. Factory Production in Nineteenth-Century Britain. Ed. Elaine Freedgood. New York: Oxford UP, 2003. 297-98. Print.

Greenhalgh, Paul. Ephemeral Vistas: The Expositions Universelles, Great Exhibitions and World’s Fairs, 1851-1939. Manchester: Manchester UP, 1988. Print.

Hoffenberg, Peter H. An Empire on Display: English, Indian, and Australian Exhibitions from the Crystal Palace to the Great War. Berkeley: U of California P, 2001. Print.

“The Imperial Object Lesson.” Saturday Review 8 May 1886: 632-33. ProQuest. Web. 24 Oct. 2011.

Kriegel, Lara. Grand Designs: Labor, Empire, and the Museum in Victorian Culture. Durham: Duke UP, 2007. Bowdoin College. Web. 9 Dec. 2011.

Levell, Nicky. Oriental Visions: Exhibitions, Travel, and Collecting in the Victorian Age. London: Horniman Museum and Gardens, 2000. Print.

Mathur, Saloni. India by Design: Colonial History and Cultural Display. Berkeley: U of California P, 2007. Print.

McGowan, Abigail. Crafting the Nation in Colonial India. New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2009. Print.

Mukharji, T.N. A Visit to Europe. Calcutta: W. Newman, 1889. Google Book Search. Web. 25 Oct. 2011.

Peripatetic. “The Colonial and Indian Exhibition.” British Architect 11 May 1886: 511-512. ProQuest. Web. 24 Oct. 2011.

Ruskin, John. “The Nature of Gothic.” The Stones of Venice. Vol. 2. London: Smith, Elder, 1853. 151-231. Google Book Search. Web. 24 Oct. 2011.

Spear, Jeffrey L. “A South Kensington Gateway from Gwalior to Nowhere.” Studies in English Literature 48.4 (2008): 911-21. JSTOR. Web. 9 Dec. 2011.

Suleri, Sara. The Rhetoric of English India. Chicago: U of Chicago P, 1992. Print.

Swallow, Deborah. “Colonial Architecture, International Exhibitions and Official Patronage of the Indian Artisan: The Case of a Gateway from Gwalior in the Victoria and Albert Museum.” Barringer and Flynn 52-67.

Tennyson, Lord Alfred. “Opening of the Indian and Colonial Exhibition by the Queen: Written at the Request of the Prince of Wales.” The Complete Poetical Works of Tennyson. Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1898. 525. Google Book Search. Web. 9 Dec. 2011.

RELATED BRANCH ARTICLES

Anne Clendinning, “On The British Empire Exhibition, 1924-25″

Anne Helmreich, “On the Opening of the Crystal Palace at Sydenham, 1854”

Audrey Jaffe, “On the Great Exhibition”

Amy Woodson-Boulton, “The City Art Museum Movement and the Social Role of Art”

ENDNOTES

[1] Alfred, Lord Tennyson, “Opening of the Indian and Colonial Exhibition by the Queen, 1886: Written at the Request of the Prince of Wales” (35-40).

[2] For more on the significance of Gwalior Gateway in this and other exhibits, see Spear and Swallow.

[3] In 1885, Liberty’s Department Store attempted to reproduce an artisan village as a promotional campaign; Mathur provides an engrossing account of its failure (36-42). See Chapter 4 in Greenhalgh for an overview of “Human Showcases” in international exhibitions.

[4] For more on Mukharji, see Mathur 60-61, 67-69.

[5] Dewan writes that illustrations of these artisans “authenticated the textual information written therein” (“Scripting South Asia’s Visual Past” 42).

[6] As Dewan writes, “Nationalist images, especially pictures of Gandhi spinning cotton, can be traced genealogically to the earlier art-school images of the native craftsman” (“Body at Work” 131).