Abstract

The Crystal Palace at Sydenham represents a number of key paradigms in Victorian culture: the emphasis upon visuality as a means of acquiring and conveying knowledge, the use of display as a vehicle of both education and entertainment, the desire to construct unifying historical narratives, and the emphasis upon rational recreation.

The sprawling enterprise of the Crystal Palace at ![]() Sydenham, which included both a vast iron and glass structure and an even larger park, was a cacophony with multifarious sights, sounds, and activities competing for the visitor’s attention. Yet, despite this dissonance, the early years of the Crystal Palace were distinguished by a discernable program. The resurrection of the

Sydenham, which included both a vast iron and glass structure and an even larger park, was a cacophony with multifarious sights, sounds, and activities competing for the visitor’s attention. Yet, despite this dissonance, the early years of the Crystal Palace were distinguished by a discernable program. The resurrection of the ![]() Crystal Palace of 1851 in its new setting at Sydenham, with an expanded architectural complex and enhanced functional prospectus, embodies the Victorian emphasis upon visuality as a means of acquiring and conveying knowledge. In addition, the new Crystal Palace was shaped by prevailing concepts of rational recreation and beneficial commerce that insisted that private and public interests could be simultaneously satisfied and lead to a stronger nation and even Empire.

Crystal Palace of 1851 in its new setting at Sydenham, with an expanded architectural complex and enhanced functional prospectus, embodies the Victorian emphasis upon visuality as a means of acquiring and conveying knowledge. In addition, the new Crystal Palace was shaped by prevailing concepts of rational recreation and beneficial commerce that insisted that private and public interests could be simultaneously satisfied and lead to a stronger nation and even Empire.

Delineating the details of reconstructing the Crystal Palace, including the sometimes contentious debates between project leaders, and recounting the wealth of displays contained within it and the park exceeds the space of this essay. Indeed, contemporaneous guidebooks struggled to provide lucid and concise accounts of the complex. Following the lead of these guidebooks, this essay focuses upon those spaces and features most frequently commented upon.

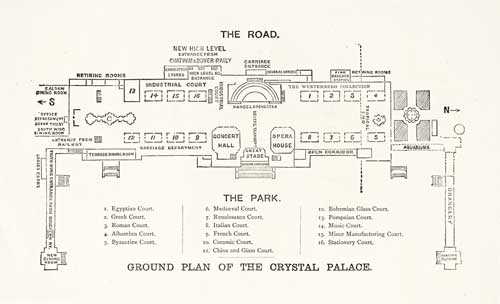

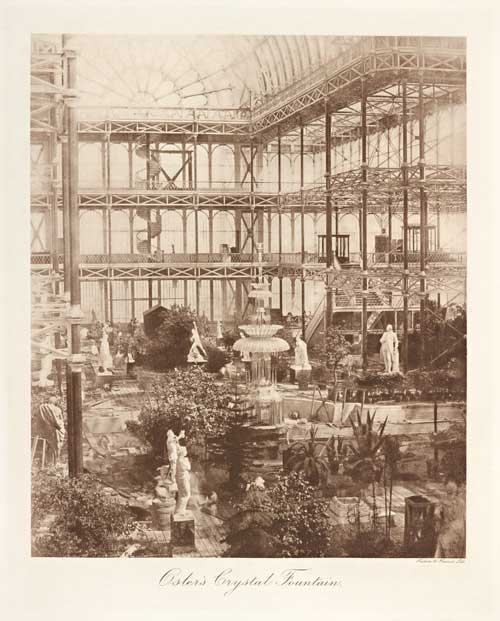

When rebuilt, the Crystal Palace retained its main architectural features—large sheets of glass held within an iron, prefabricated framework. The footprint and scale, however, were much larger; it rose up five stories instead of the original three and, as J. R. Piggott points out, “the new Palace was nearly 50 per cent larger in cubic content than the one in Hyde Park, and had almost twice the surface of glass” (40). The final design, with its use of a crowning dome and side aisles, strongly echoed that of cathedrals, arguably even more so than had the first. The vocabulary used to denote the internal divisions of space—nave and transepts—reinforced such associations. (See Fig. 2.) Joseph Paxton, working with the contractors Fox and Henderson, was responsible for the building and grounds and Owen Jones and Matthew Digby Wyatt were charged with the design of the Fine Art Courts that were the dominating feature of the interior, alongside the horticultural and ethnographic displays. Over time, new spaces were added to the interior to support music and other entertainments; for example, in 1869 the Opera Theater opened.[2]The new Crystal Palace, as originally conceived, was proposed to be an ideal means by which education, recreation, and amusement could be delivered to the people (except on Sundays when it was closed) while also supporting the commercial interests of transportation and manufacturing. While the costs of this complex balancing act consistently exceeded the profits, leading to the eventual bankruptcy of the Crystal Palace Company in 1911, this over-reaching ambition is nonetheless worthy of close examination for the paradigms of Victorian culture it reveals.

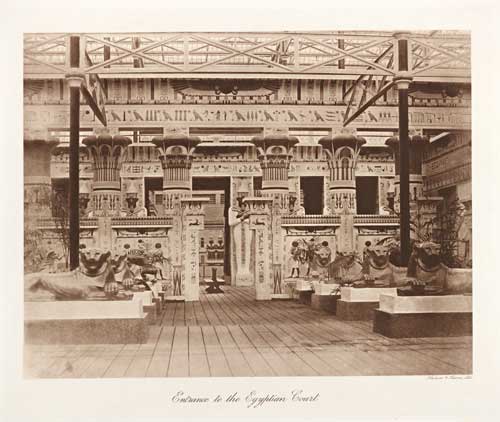

The primary aim of the Fine Arts Courts was educational, and to achieve this goal the company directors proposed “a complete historical illustration of the arts of sculpture and architecture from the earliest works of ![]() Egypt and Assyria down to modern times, comprising casts of every celebrated statue in the world, and restorations of some of its most remarkable monuments” (The Sydenham Crystal Palace Expositor 3). Embedded in this brief overview are a number of critical concepts—that a unitary historical narrative was possible, that the most effective way to convey this narrative was visually, and that reproductions were as valid as originals in demonstrating this history.

Egypt and Assyria down to modern times, comprising casts of every celebrated statue in the world, and restorations of some of its most remarkable monuments” (The Sydenham Crystal Palace Expositor 3). Embedded in this brief overview are a number of critical concepts—that a unitary historical narrative was possible, that the most effective way to convey this narrative was visually, and that reproductions were as valid as originals in demonstrating this history.

The latter was a well-established premise in arts education; European art academies had long used copies of Greek and Roman statues to teach the principles of good design. But this practice intensified in the Victorian age when new manufacturing means and more extensive and faster transportation networks stimulated the production and circulation of copies that became founding collections for many provincial museums in the United Kingdom. Thus Jones and Wyatt, while the building was under construction, were sent to the continent “to obtain models of the principal works of art in Europe.” (The Sydenham Crystal Palace Expositor 2). In short, the Crystal Palace modeled our contemporary understanding of the encyclopedic museum, whereby the history of art is illustrated by examples drawn from diverse traditions and cultures. But whereas museums today prize the authentic and original, the Victorians were hungry for the best-known examples, so that the Crystal Palace also closely resembled the Grand Tour enacted under one roof.[3] As the Guide to the Palace and Park (1878) explained, “the Fine Arts Courts . . . contain fac-similes of the actual remains of the Architecture and Sculpture of the Successive ages and schools, and are intended to give the untravelled visitor the same advantage which has been hitherto the privilege of the traveller only” (2).

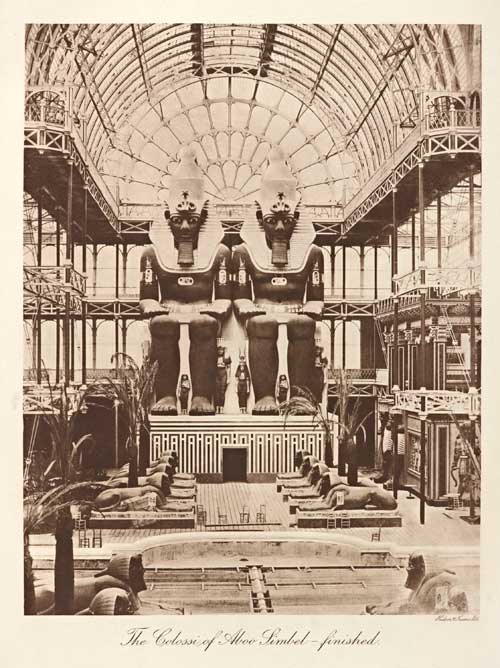

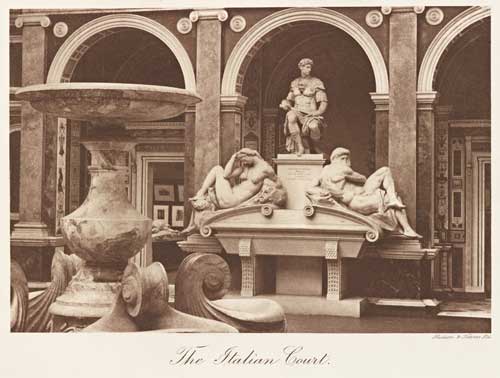

The desire to establish unitary historical narratives that demonstrated the rise and fall of civilizations leading up to the primacy of the modern age—i.e. the modern Briton—also became particularly pronounced in the Victorian age with what has been dubbed Whig history. It is worth remembering that art and architectural history were very much in formation in this period, so that Jones and Wyatt were contributing to the formation of these discourses, as opposed to reflecting already established frameworks. Jones, in the introduction to his guide to the Alhambra Court, explained that the new Crystal Palace hoped to rectify the defects of the 1851 exhibition by offering “the history of the civilisation of the world” displayed in such a way that enabled comparative analysis and would lead visitors to “more fully recognise the good and the evil which pervade each form of art.” Even more importantly, he hoped that visitors would extract from the diversity of examples “general principles which survive from generation to generation to become stepping-stones for future progress” while also learning how architectural styles developed out of the “religion, habits, and modes of thought of the nations which produced them, and may be said to be the material expression of their wants, faculties, and sentiments, under the influence of climate and of materials at command” (7). In short, Jones wanted both a contextual and idealist form of history. His concept of style was informed by Hegelianism; he argued that “each of these styles, whether primary, secondary, or tertiary, was constantly in a state of progression” (8). This theory informed the decision to use historical geography and style to structure the individual courts. The tour as illustrated history began with the Egyptian Court, followed by the Greek, Roman, Alhambra, and Assyrian Courts along one side of the Nave. (See Fig. 3.) The Assyrian, or Nineveh Court, was designed by James Fergusson, and included colossal figures from Abu Simbel that were destroyed by fire in 1866. (See Fig. 4.) On the other side of the nave, and under the supervision of Wyatt, were the Byzantine, Medieval, Renaissance, Elizabethan, and Italian Courts; the latter extended the narrative to the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries with the replica of the upper arcade of the Farnese Palace, the inclusion of Michelangelo’s Tomb of Lorenzo de Medici and sculptures by Bernini, and the display of watercolor replicas of Old Master paintings by artists ranging in date from Giotto to Murillo, among other features. (See Fig. 5.]While one of the early guidebooks questioned whether the Fine Art Courts could be understood easily by those without “an amount of learning,” or possibly even “profound erudition,” Jones argued that the complex would combat “the ignorance of the public” (The Sydenham Crystal Palace Expositor 6; Jones 16). Jones’s reasoning was that the Fine Art Courts addressed “themselves directly to the eye” and, once visual attention was secured, would lead to “study and reflection”; that is, appreciation and comprehension were primarily and initially visual (16). Likewise, he argued that designers and manufacturers, as well as patrons, could learn principles of good design from studying examples collected at the New Crystal Palace, thus reiterating one of the key principles for organizing the Great Exhibition of 1851.

From the Fine Art Courts, the visitor then proceeded to the Stationery Court, devoted to printing and publishing, then to the Birmingham and Sheffield Courts, which showcased the manufactured products of those locales. Thus the process of learning through the eye carried over from the history of art and architecture to modern production. The shift from past to present also meant a change from the disinterested to the commercial in that the Industrial Courts also contained stalls of products for sale. Art was sold in the Picture Gallery, which included both copies after the Old Masters as well as original works representing “the British . . . the French, Belgian, Dutch and the German Schools” (Guide to the Palace and Park 19). While having objects such as art works or manufacturing products appear in both educational and commercial settings may strike us today as disingenuous, the Sydenham Crystal Palace Expositor rationalized that all displays were instructional and “must teach us, if viewed aright, that progress and prosperity depend as much on commerce as on internal riches, and that all the members of the great human family may promote each other’s happiness and their Maker’s glory, by spreading the blessings of civilisation” (145).

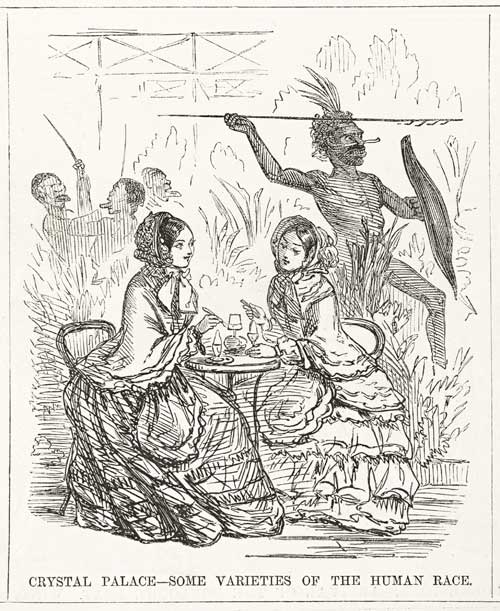

Inherent in this rhetoric was the concept that this mission would be best achieved by displaying exemplary specimens. (See Fig. 6.) This model of didacticism carried over to the selection of plants which, like the Fine Art Courts with their polychromy decoration, tended towards the spectacular, as in the case of the Victoria Regia, waterlilies from theThese plant specimens were also in keeping with the concept of visual education, which was the organizing rubric for the scientific displays as Samuel Phillips explained in his guide to the Crystal Palace: “All those sciences, an acquaintance with which is attainable through the medium of the eye, were allotted their specific place, and Geology, Ethnology, and Zoology were taken as best susceptible of illustration” (18). Phillips acknowledged that, given the ![]() British Museum’s scope of work, the inclusion of natural history or natural science topics at the Crystal Palace might seem redundant, but he clarified that at the Palace they were treated differently than at the British Museum. Rather than isolating each specimen, at the Palace animals, plants, and even people (in the form of casts) were grouped—in what might be called tableaux vivant—in a manner “both instructive and amusing” to “afford a clearer conception than can be obtained elsewhere of the manner in which the varieties of man, animals, and plants are distributed over the globe” (117).

British Museum’s scope of work, the inclusion of natural history or natural science topics at the Crystal Palace might seem redundant, but he clarified that at the Palace they were treated differently than at the British Museum. Rather than isolating each specimen, at the Palace animals, plants, and even people (in the form of casts) were grouped—in what might be called tableaux vivant—in a manner “both instructive and amusing” to “afford a clearer conception than can be obtained elsewhere of the manner in which the varieties of man, animals, and plants are distributed over the globe” (117).

Figure 7: John Leech, “Crystal Palace—Some Varieties of the Human Race,” from “Punch’s Almanack for 1855”

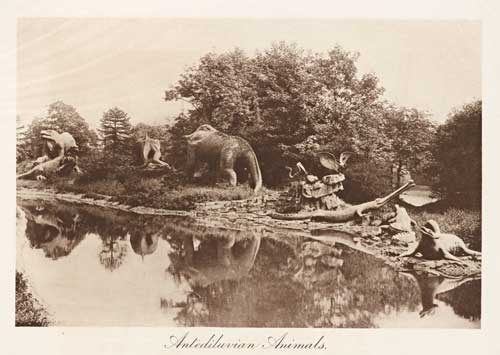

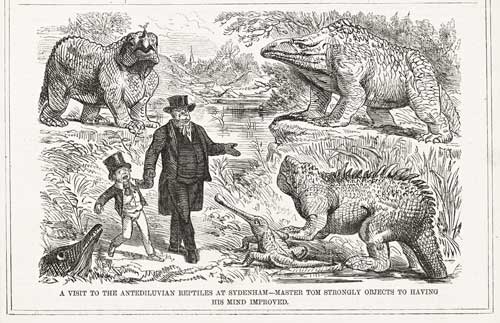

Figure 9: John Leech, “A Visit to the Antediluvian Reptiles at Sydenham…,” from “Punch’s Almanack for 1855”

William Michael Rossetti addressed this question of how best to tell history in his response to the Crystal Palace. He distinguished between providing insight to the past through “actual fragments” —the singular work of art or specimen—or reconstructions, such as those created by Hawkins and Owens (51). Rossetti recognized that reconstructions allowed the visitor to “get general and distinct notions on the subject after a visit of a few hours, such as no quantity of unsystematic piecemeal reading or helpless inspection of authentic débris would have supplied him with” (52). Moreover, the presentations at the Crystal Palace created “a linked chain of sequence and divergence whose significance it is difficult to miss altogether” (52). Nonetheless, he raised questions about using reconstructions as didactic material. The copy, he noted, was often inferior to the original and misrepresented details. (It is worth pointing out that these objections were glossed over by such texts as A Handbook to the courts of Modern Sculpture, authored by Anna Jameson, whose scholarly expertise endowed the cast sculpture collection with value and significance.) Moreover, Rossetti warned, the designers’ conjectures—as in the case of polychromy—might be taken for fact. In the end, however, he concluded that the Crystal Palace’s “comprehensiveness and vividness” outweighed its defects (53). Rossetti’s essay reveals the success of the Crystal Palace as an accessible encyclopedia that enticed the eye.

Just as the dinosaur displays extended the historical and scientific narratives found within the Palace, the garden grounds continued the vocabulary of design styles and showcased technological achievements. In addition, the park, over time, registered the increasing popularization of personal health and fitness as well as group sport and mechanical entertainments. New spaces were carved out, for example, to support such activities as cricket and football (the park was the site of the football association’s cup final from 1890 to 1914) and a flying machine. At the heart of Paxton’s design for the grounds was a series of waterworks intended to rival those of ![]() Versailles and other continental palaces. This feat required an extensive system of water reservoirs, towers, piping and pumping. The fountains were set in the midst of a landscape design that judiciously blended the formal with informal. The latter mapped onto the two leading, fashionable gardening styles—the Italian and the English Landscape. The Italian denoted highly architectural garden designs, derived from popular understandings of the Italian Renaissance. At the Crystal Palace, Paxton adopted this manner for the terraces carved into the hillside; along the parapet of the first terrace were found “allegorical statues of the most important commercial and manufacturing countries in the world, and of the chief industrial cities of England and

Versailles and other continental palaces. This feat required an extensive system of water reservoirs, towers, piping and pumping. The fountains were set in the midst of a landscape design that judiciously blended the formal with informal. The latter mapped onto the two leading, fashionable gardening styles—the Italian and the English Landscape. The Italian denoted highly architectural garden designs, derived from popular understandings of the Italian Renaissance. At the Crystal Palace, Paxton adopted this manner for the terraces carved into the hillside; along the parapet of the first terrace were found “allegorical statues of the most important commercial and manufacturing countries in the world, and of the chief industrial cities of England and ![]() France” (Phillips 179). These highly symmetrical and geometrically organized terraces represented the epitome of this style (Elliott 110). On the lower terrace, flowers were presented in broad masses of color in beds that eventually set the tone for public parks (Elliott 134). These designs became increasingly complex; in 1875, for example, the grounds superintendent created six butterfly-shaped beds (Elliott 156).

France” (Phillips 179). These highly symmetrical and geometrically organized terraces represented the epitome of this style (Elliott 110). On the lower terrace, flowers were presented in broad masses of color in beds that eventually set the tone for public parks (Elliott 134). These designs became increasingly complex; in 1875, for example, the grounds superintendent created six butterfly-shaped beds (Elliott 156).

Such floral displays and accompanying waterworks were distinguished from the English landscape style, derived from Capability Brown, which was intended to mimic scenes found in nature with “irregularly-bounded pieces of water which delight the English eye, the shrubberies, the noble groups of trees, the winding walks, the gentle undulations, and pleasant slopes” (Phillips 175). In between these two zones Paxton introduced “a mixed, or transitional style, combining the formality of the one school with the freedom and natural grace of the other” (Phillips 175). In the gardens, experiential learning, now involving bodily movement as well as roving eyes, became both more holistic and less explicit. The park land, with its terraces, fountains, cricket ground, football ground, tennis grounds, maze, bandstands, flying machine and panorama building exemplified the claim of the auctioneers, charged with selling the complex in 1911, that the Crystal Palace “while remaining the Palace of the People’s Instruction . . . also became the Palace of the People’s Pleasures” (The Crystal Palace Sydenham, To be sold 19).

1911 marked both the apogee of the Crystal Palace as well as the first discernible step in what, in hindsight, became a slow decline. In 1911, the Crystal Palace hosted the Pageant of London in conjunction with the Festival of Empire, two of many events that brought a host of foreign dignitaries to the grounds. The Festival of Empire was an opportunity not only to refurbish the structure and park, but also to underscore how the rhetoric of empire was associated with that of the progress of civilizations as described at the Palace (Hoffenberg; Ryan). But in that same year, the history of excessive expenditures caught up with the Crystal Palace Company and their holdings were put on the auction block. Lord Plymouth purchased the structure on behalf of the nation and oversight was put in the hands of a board of Trustees. At last the Crystal Palace really belonged to the people, but its subsequent history was one of repurposing; it was used for a naval depot and the Imperial War Museum, among other uses. Its former mission, which always had a cobbled-together coherency—“amusement and recreation, instruction, and commercial utility”—was now diluted and fragmented. In 1936, another fire led to the final destruction of the new Crystal Palace.

HOW TO CITE THIS BRANCH ENTRY (MLA format)

published April 2012

Helmreich, Anne. “On the Opening of the Crystal Palace at Sydenham, 1854.” BRANCH: Britain, Representation and Nineteenth-Century History. Ed. Dino Franco Felluga. Extension of Romanticism and Victorianism on the Net. Web. [Here, add your last date of access to BRANCH].

Altick, Richard. The Shows of London. Cambridge: Belknap Press, 1978. Print.

Auerbach, Jeffrey. The Great Exhibition of 1851: a nation on display. New Haven: Yale UP, 1999. Print.

The Crystal Palace Sydenham, To be sold by Auction, pursuant to an order of the High Court of Justice… London: Messrs. Knight, Frank & Rutley, 1911. Print.

Doyle, Peter and Eric Robinson. “The Victorian ‘Geological Illustrations’ of Crystal Palace Park.” Proceedings of the Geologists’ Association 104, 181-194. Print.

Driver, Felix and David Gilbert, eds. Imperial Cities, Landscape, Display and Identity. Manchester: Manchester UP, 1999. Print.

Elliott, Brent. Victorian Gardens. Portland: Timber Press, 1986. Print.

Guide to the Palace and the Park by Authority of the Directors. London: Crystal Palace P; Charles Dickens and Evans, 1878. Print.

Hassam, Andrew. “Portable Iron Structures and Uncertain Colonial Spaces at the Sydenham Crystal Palace.” Driver and Gilbert 174-193. Print.

Herbert, Trevor and Arnold Myers. “Music for the Multitudes: accounts of brass bands entering Enderby Jackson’s Crystal Palace contests in the 1860s.” Early Music 38 (2010): 571-584. Print.

Hobhouse, Hermione. The Crystal Palace and the Great Exhibition: Art, Science and Productive Industry: a history of the Royal Commission for the Exhibition of 1851. London: Athlone, 2002. Print.

Hoffenberg, Peter. An Empire on Display: English, Indian, and Australian Exhibitions from the Crystal Palace to the Great War. Berkeley: Uof California P, 2001. Print.

Jameson, Anna. A Handbook to the Courts of Modern Sculpture. London: Crystal Palace Library, and Bradbury & Evans, 1854. Print.

Jones, Owen.The Alhambra Court in the Crystal Palace. London: Crystal Palace Library, 1854. Print. Print.

Kay, Alison C. “Villas, Values and the Crystal Palace Company, c. 1852-1911,” The London Journal 33 (March 2008): 21-39. Print.

Layard, Herny. The Nineveh Court in the Crystal Palace. London: Crystal Palace Library, 1854. Print.

Marshall, Nancy Rose. “‘A Dim World, Where Monsters Dwell’, The Spatial Time of the Sydenham Crystal Palace Dinosaur Park.” Victorian Studies 49.2 (2007): 286-301. Print.

—. City of Gold and Mud, Painting Victorian London. New Haven and London: Yale UP for the Paul Mellon Centre for Studies in British Art, 2012. Print

Musgrave, Michael. The Musical Life of the Crystal Palace. Cambridge: Cambridge UP, 1995. Print.

Phillips, Samuel. Guide to the Crystal Palace and Park. 2nd. ed. London: Bradbury and Evans, 1854. Print.

Piggott, J. R. Palace of the People, The Crystal Palace at Sydenham, 1854-1936. London: Hurst & Company, 2004. Print.

“Punch’s Almanack for 1855,” Punch vol. 28 (1855): unpaginated.

Qureshi, Sadiah. Peoples on Parade: Exhibitions, Empire, and Anthropology in Nineteenth-Century Britain. Chicago: U of Chicago P, 2011. Print.

Rossetti, William Michael. Fine Art, Chiefly Contemporary: notices re-printed, with revisions. London: Macmillan and Co., 1867. Print.

Ruskin, John. The Opening of the Crystal Palace: considered in some of its relations to the prospects of art. London: Smith, Elder and Co., 1854. Print.

Ryan, Deborah. “Staging the Imperial City: the Pageant of London, 1911.” Driver and Gilbert 117-135. Print.

Scharf, George. The Roman court: (including the antique sculptures in the nave) erected in the Crystal Palace by Owen Jones. London: Crystal Palace Library, 1854. Print.

Smith, Alison. The Victorian Nude, Sexuality, Morality and Art. Manchester: Manchester UP, 1996. Print.

The Sydenham Crystal Palace Expositor. London: J. S. Virtue, [1854]. Print.

Wyatt, M. Digby and J. B. Waring. The Byzantine and Romanesque Court in the Crystal Palace. London: Crystal Palace Library and Bradbury & Evans, 1854. Print.

—. The Italian Court in the Crystal Palace. London: Crystal Palace Library and Bradbury & Evans, 1854. Print.

—. The Medieval Court in the Crystal Palace. London: Crystal Palace Library and Bradbury & Evans, 1854. Print.

—. The Renaissance Court in the Crystal Palace. London: Crystal Palace Library and Bradbury & Evens, 1854. Print.

RELATED BRANCH ARTICLES

Aviva Briefel, “On the 1886 Colonial and Indian Exhibition”

Anne Clendinning, “On The British Empire Exhibition, 1924-25″

Pamela Fletcher, “On the Rise of the Commercial Art Gallery in London”

Audrey Jaffe, “On the Great Exhibition”

Amy Woodson-Boulton, “The City Art Museum Movement and the Social Role of Art”

[1] For a fulsome account of the history of the Crystal Palace at Sydenham, see J. R. Piggott, Palace of the People, The Crystal Palace at Sydenham 1854-1936 (London: Hurst & Company, 2004) to which I am greatly indebted.

[2] For more on music at the Crystal Palace, which will not be discussed in this essay, readers are directed to Musgrave, The Musical Life of the Crystal Palace, for an overview, and, for a closer examination of one type of music, Trevor Herbert and Arnold Myers, “Music for the Multitudes.”

[3] Many of the plaster casts sourced by Jones and Wyatt also differed from their original versions because a prominent faction, led by a number of prominent Church leaders, campaigned against nudity. Shortly before the opening of the exhibition, they published a petition in The Times requesting “but a small thing, not at all a sacrifice in point of artistic beauty—viz. the removal of the parts which in ‘the life’ ought to be concealed, although we are also desirous that the usual leaf may be adopted” (Piggott 52). Historian J. R. Piggott notes that Owen Jones argued against this practice and nude statues without fig-leaves could be found in the Fine Art Courts (Piggott 52). Art historian Alison Smith, in her study of the controversies surrounding the representation of the nude in Victorian culture, recounts how a young female member of the Plymouth Brethren was so disturbed by the nude statues found in the Sculpture Gallery at the Crystal Palace that she began to smash the figures (Smith 16).