James Chandler, “On Peterloo, 16 August 1819”

“Peterloo” is the nickname that came to be given to the events of 16 August 1819, when a demonstration on St. Peter’s Field in Manchester in behalf of Parliamentary Reform was broken up by armed force, leaving about a dozen demonstrators dead and many others wounded by hoof and saber. Its claim to distinction in modern social and political history is that, with estimates of the crowd running to 60,000 people, it was probably at the time the largest mass peaceful demonstration ever assembled. Non-violent protest has become a fact of political life over the nearly two centuries since Peterloo. We now associate these kinds of events with names like Mahatma Gandhi and Martin Luther King, Jr. but the Reform Movement that took shape in Britain in the period after the defeat of Napoleon’s forces at Waterloo had evolved what was then a new set of tactics.

Florence S. Boos, “The Socialist League, founded 30 December 1884”

The Socialist League was one of several early socialist groups which arose in Great Britain during the 1880s. Among these, the League was distinctive for its eclectic membership and its focus on education and outreach as the most effective means to social change. Its notable members included William Morris, Tom Maguire, Andreas Scheu, Bruce Glasier, and for a time, Friedrich Engels, Eleanor Marx, and Edward Aveling. During its four years of greatest activity from 1885 through 1889, its vigorous program of lectures, open-air meetings, and publications, including Commonweal, reached a wide audience through campaigns on behalf of free speech, miners’ strikes, an international workers’ movement, and the reorganization of society “from the root up.” Its internationalism, strong support for the Second International, and consistent anti-imperialism gave its revolutionary ideals a broad, forward looking cast. Its focus on education, outreach, and alternative forms of social organization also attracted writers, artists and intellectuals who promoted its holistic ideals through creative works and contributed to its journal Commonweal. On the other hand, as an organization founded before the election of working-class representatives seemed feasible, its continued commitment to advocacy and “pure” socialism—as opposed to party politics—ultimately rendered it less viable than more pragmatically oriented groups such as the emerging Independent Labour Party.

Eleanor Courtemanche, “On the Publication of Fabian Essays in Socialism, December 1889″

The Fabian Essays, published in 1889 by an intellectual London club called the Fabian Society, aimed to make socialism palatable to a largely suspicious British public and became a surprise bestseller. The volume was edited by George Bernard Shaw, who was a leading figure in the Fabian Society before his career as a dramatist. In the Fabian Essays, the Fabians distanced themselves from the insurrectionary radicalism of both Hyndman’s Social Democratic Federation and Morris’s Socialist League, claiming instead that Britain was inevitably and gradually evolving into a sensible socialist state. The Fabians’ advocacy of pragmatic socialist parliamentary politics helped pave the way for the rise of the Labour Party in 1900.

Priti Joshi, “1857; or, Can the Indian ‘Mutiny’ Be Fixed?”

In the 150 years since it occurred, little about the events that shook northern India in the waning days of the East-India Company’s rule has been fixed. The skeletal facts are seldom contested, but their meanings so disputed that what is known appears to recede. Take, for instance, the nomenclature: long known as the “Indian Mutiny,” the events under scrutiny were neither “Indian” (in any pan-Indian or collective sense) nor only a “mutiny.” Alternatives abound—Sepoy Mutiny; Sepoy War; Revolt of 1857; the Uprising of 1857; the Rebellion of 1857; the Great Rebellion; the First War of Independence—each offering an interpretive gloss on the May 1857-June 1858 events. This essay offers an overview of key nodes of debate—who participated and why? who led whom? how planned were the events? how unified were actors—in the current historiography of 1857.

Jo Briggs, “The Second Boer War, 1899-1902: Anti-Imperialism and European Visual Culture”

The Second Boer War, part of the “Scramble for Africa” among European powers, was fought from 1899 and 1902 in what is now South Africa between British Imperial forces and the Transvaal Republic and Orange Free State. The war occurred during the period of so-called New Imperialism (ca. 1880 to 1914) characterized by rising nationalism, racism, Social Darwinism, and genocidal thinking. Occurring roughly in the middle of this period, the Second Boer War became the focal point for a variety of hopes, anxieties, politics, and ideologies. An examination of periodicals created specifically to protest against the war shows that the conflict resonated within diverse local contexts, revealing the complex interplay between global events and local politics.

Lorraine Janzen Kooistra, “The Moxon Tennyson as Textual Event: 1857, Wood Engraving, and Visual Culture”

By convention the launch of the so-called “golden age” of wood-engraved illustration in Britain, also known as “the sixties,” is Edward Moxon’s publication, in May 1857, of Alfred Tennyson’s Poems, with 54 wood-engraved illustrations designed by 8 artists, including the Pre-Raphaelites John Everett Millais, William Holman Hunt, and Dante Gabriel Rossetti. Although the Moxon Tennyson was neither a commercial nor critical success on first publication, before the decade was out its Pre-Raphaelite designs were considered a touchstone for artistic illustration, a reputation that continues today. Without disputing the significance of this aesthetic achievement, I want to shift critical focus to the Moxon Tennyson’s status as mass-produced work of art in the age of mechanical reproduction. My interest here is in how its visual communication was expressed through its reproductive technology at the historical moment of its production and reception. This essay re-positions the Moxon Tennyson as a textual event by reading it in the context of documentary, satiric, and artistic wood-engraved images selected from the crucial six-month period after its publication. By situating the Pre-Raphaelite illustrations for Tennyson’s Poems in relation to representations in the public press of such disparate events as the Art Treasures of the United Kingdom Exhibition in Manchester, the reportage on Indian uprisings at Meerut and Cawnpore, the Matrimonial Causes Act, and the Christy Minstrels show in London, I aim to show the complex ways in which the Moxon Tennyson was a worldly event, caught up in, and contributing to, ways of seeing and knowing in 1857.

Marjorie Stone, “Joseph Mazzini, English Writers, and the Post Office Espionage Scandal: Politics, Privacy, and Twenty-First Century Parallels”

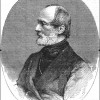

In 1844, an English radical MP affiliated with the Chartist movement petitioned the House of Commons, charging that Sir James Graham, Secretary of State for the Home Office, had secretly authorized the opening of the letters of exiled Italian nationalist and resident of London, Joseph Mazzini, spying upon their contents. The ensuing Post Office espionage scandal is a pivotal event in British and European history, represented—like Mazzini himself—from conflicting perspectives and shaping a host of subsequent developments. It provoked “anti-Graham” envelopes and parodies in Punch, intensified British sympathy for the Italian liberation and unification movement for which Mazzini was the principal theorist, and influenced British policy towards the 1847-49 revolutions in Italian states struggling for independence from Austrian overlords and autocratic Bourbon kings. The scandal and the networks it forged also shaped British party politics, Chartist international alliances, and emerging conceptions of rights to privacy and limits on state surveillance. Mazzini, revered as an apostle by many, was viewed as a dangerous subversive by many others, including the Pope and Prince Klemens von Metternich, Foreign Secretary to the Austrian Empire, later one of Henry Kissinger’s diplomatic models. As the scandal unfolded, evidence indicated that Graham and the Foreign Secretary Lord Aberdeen shared information from Mazzini’s letters with the Austrians, linking British espionage to the execution of the Bandiera brothers, Italian revolutionaries, in Naples in July 1844. This essay surveys diverse responses to Mazzini and the literary and cultural as well as the political repercussions of the 1844 scandal. Prominent English writers, notably Thomas Carlyle, came to Mazzini’s defence, especially indignant over violations of privacy, while others—including Robert Browning, Elizabeth Barrett Browning, George Meredith, Algernon Charles Swinburne, and George Eliot—went on to write works influenced by the charismatic, controversial Italian nationalist. An epilogue notes some of the 1844 event’s parallels with current controversies over communications hacking (WikiLeaks, the News of the World phone hacking) and appropriate limits on state secrecy and surveillance in the wake of 9/11, 7/7, anti-terrorism legislation, and the “rendition” of information and/or persons such as Canadian-Syrian Maher Arar to oppressive regimes by democratic countries.

Zarena Aslami, “The Second Anglo-Afghan War, or The Return of the Uninvited”

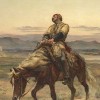

The Second Anglo-Afghan War grew out of longstanding tensions between Russia and Britain over Britain’s prized colonial possession of India. In my account of the Second Anglo-Afghan War, I would like to emphasize two main themes. First, Afghanistan occupied an anomalous position in the British Empire. The British did not seek to colonize it or conquer it. Rather, they sought to install a sovereign who would be sympathetic to British interests, allow the British to control Afghan foreign policy, and forbid Russia from entering its borders. Second, by granting sovereignty to chosen leaders, British actions toward Afghanistan complicated the notion of sovereignty as such. The case of Afghanistan ought to remind us that it is extremely difficult to generalize how imperial power functioned across the nineteenth century and, moreover, that imperial power, in Afghanistan and other sites, was not homogeneous but rather could emanate from multiple empires at cross purposes over a single location.

Julie Codell, “On the Delhi Coronation Durbars, 1877, 1903, 1911”

This essay explores the three Delhi Coronation Durbars and their relationship to topics of spectacle, imperial policy, visual culture, modern media, and Indian and British responses to these events.

Antoinette Burton, “On the First Anglo-Afghan War, 1839-42: Spectacle of Disaster”

This essay surveys representations of the first Anglo-Afghan campaign (1839-42) in an effort to recast the narrative of the war so that it accounts for the variety of native actors in the war and in the geopolitical crises leading up to it. The “Great Game” may have been a “tournament of shadows” between the British and the Russians, but it was entangled by both local dynastic conflicts and a challenging, even insurgent, physical terrain as well. Though the British officially won the war, Afghanistan was hardly secure either during the occupation or in the decades that followed. In that sense, the first Anglo-Afghan war presaged a century of precarious imperial power on the frontier of the Raj.