Abstract

In 1844, an English radical MP affiliated with the Chartist movement petitioned the House of Commons, charging that Sir James Graham, Secretary of State for the Home Office, had secretly authorized the opening of the letters of exiled Italian nationalist and resident of London, Joseph Mazzini, spying upon their contents. The ensuing Post Office espionage scandal is a pivotal event in British and European history, represented—like Mazzini himself—from conflicting perspectives and shaping a host of subsequent developments. It provoked “anti-Graham” envelopes and parodies in Punch, intensified British sympathy for the Italian liberation and unification movement for which Mazzini was the principal theorist, and influenced British policy towards the 1847-49 revolutions in Italian states struggling for independence from Austrian overlords and autocratic Bourbon kings. The scandal and the networks it forged also shaped British party politics, Chartist international alliances, and emerging conceptions of rights to privacy and limits on state surveillance. Mazzini, revered as an apostle by many, was viewed as a dangerous subversive by many others, including the Pope and Prince Klemens von Metternich, Foreign Secretary to the Austrian Empire, later one of Henry Kissinger’s diplomatic models. As the scandal unfolded, evidence indicated that Graham and the Foreign Secretary Lord Aberdeen shared information from Mazzini’s letters with the Austrians, linking British espionage to the execution of the Bandiera brothers, Italian revolutionaries, in Naples in July 1844. This essay surveys diverse responses to Mazzini and the literary and cultural as well as the political repercussions of the 1844 scandal. Prominent English writers, notably Thomas Carlyle, came to Mazzini’s defence, especially indignant over violations of privacy, while others—including Robert Browning, Elizabeth Barrett Browning, George Meredith, Algernon Charles Swinburne, and George Eliot—went on to write works influenced by the charismatic, controversial Italian nationalist. An epilogue notes some of the 1844 event’s parallels with current controversies over communications hacking (WikiLeaks, the News of the World phone hacking) and appropriate limits on state secrecy and surveillance in the wake of 9/11, 7/7, anti-terrorism legislation, and the “rendition” of information and/or persons such as Canadian-Syrian Maher Arar to oppressive regimes by democratic countries.

The summer of 1844 was far from a sleepy one for politicians, the press, or the public in England. On the contrary, a scandal ignited a firestorm of controversy over government surveillance and the right to privacy. The exiled Italian nationalist Guiseppe Mazzini had been living in London since 1837, where, given his support for enhancing the democratic rights of the “people” in Italian states, Britain and other European countries, he developed close relationships with leading figures in the Chartist movement and other English radicals. A petition presented by the radical MP Thomas Slingsby Duncombe to the House of Commons on 14 June charged that Sir James Graham, Secretary of State for the Home Office, had authorized the interception and secret opening of Mazzini’s letters as they passed through the Post Office, spying upon their contents. The English Post Office espionage scandal of 1844 is a pivotal, politicized historical event, one that has been recounted countless times, and represented—like Mazzini himself—from diverse perspectives. It made the name of Mazzini a household word throughout much of England, spilled over into material culture artefacts (cartoons in Punch as well as “anti-Graham” envelopes), and intensified sympathy in Britain for the struggle to liberate and unify ![]() Italy, captured by the resonant term Risorgimento or “rebirth,” for which Mazzini was the chief ideologue and polemicist. (See Alison Chapman, “On Il Risorgimento.”) The creation in London of the Society of the Friends of Italy in 1851 grew in part out of alliances formed or cemented in the 1844 espionage scandal, especially with Chartist sympathizers and radical MPS who turned increasingly to international networks following the culmination and collapse of Chartism with the third Chartist petition of 1848.

Italy, captured by the resonant term Risorgimento or “rebirth,” for which Mazzini was the chief ideologue and polemicist. (See Alison Chapman, “On Il Risorgimento.”) The creation in London of the Society of the Friends of Italy in 1851 grew in part out of alliances formed or cemented in the 1844 espionage scandal, especially with Chartist sympathizers and radical MPS who turned increasingly to international networks following the culmination and collapse of Chartism with the third Chartist petition of 1848.

One reason for enduring fascination with the story of Mazzini and the Post Office scandal is that the Italian revolutionary nationalist was such a complex, contradictory figure himself, viewed in strikingly diverse ways at differing stages of his career by his continental, English and North American contemporaries. Revered from Italy to England, the United States, and South America as a visionary, charismatic political theorist by affiliates of “Young Italy,” the organization he founded, he was also condemned and pursued as a violent, plotting terrorist by those in positions of political power in the conglomeration of separate states that made up what is now Italy. Another reason for the 1844 scandal’s impact is that it brought to the fore conflicts between the individual and the state shaped by an increasingly international world order and the rise of a mass information society with increasingly modernized communications systems. The latter included the Uniform Penny Post introduced in England in 1840 by Sir Rowland Hill, facilitating speedy and cheap delivery of letters through the introduction of the postage stamp and the rapidly developing railway system (Hill and Hill). A third reason for continuing interest in the English government’s covert spying on Mazzini’s letters in 1844 is that the incident plays a key role in the histories of surveillance and privacy, as studies such as Roy Porter’s Plots and Paranoia or David Vincent’s The Culture of Secrecy indicate. Indeed, controversy over the 1844 case strikingly anticipates the debates that citizens in numerous countries grapple with today over “securitizing” the state and “renditions” of information in the wake of anti-terrorism legislation provoked by the events of 9/11 in the US and 7/7 in the UK (as in the Maher Arar case, as I note below). And most obviously, of course, controversy over the secret opening of Mazzini’s letters speaks to debates over changing standards and protocols for privacy, as well as diplomatic secrecy, that seem increasingly fraught today with the transformations wrought by electronic media and the hacking of phones (the News of the World scandal), emails, and government documents (the WikiLeaks of Julian Assange and associates).

Mazzini the Man: Apostle, Revolutionist, and Conspirator

In many eyes—especially but not exclusively radical eyes—the man whose motto was “Dio e popolo” (“God and the people”) was a prophet and martyr for the Italian nationalist cause and for democratic rights of many kinds. Mazzini dedicated his life, personal affections, safety, and genius as a writer and theoretical thinker for a united and free Italy. But England, where he took refuge in London as a political exile in January 1837, was in his own words, “my real home, if I have any” (qtd. in Trevelyan, “Introduction” xxi). One of Mazzini’s most eminent and authoritative biographers, Denis Mack Smith,[1] recounts the pleasure the philosopher and economist John Stuart Mill experienced in September 1837 at meeting the “celebrated Mazzini, . . . the most eminent conspirator and revolutionist now in Europe,” and the “most accomplished and in every way superior” foreigner he had thus far known (qtd. in Smith 24). Initially keeping a low profile in London and struggling to make an income as a man of letters writing articles for the Westminister Review, The Monthly Chronicle, Tait’s Edinburgh Magazine, and The British and Foreign Review, Mazzini—with his charismatic personality, learning, love of literature and music, and patriotic devotion to the Italian cause—won the esteem and friendship of many English writers and public figures. The most comprehensive consideration of these literary and political relationships remains Harry W. Rudman’s erudite and engaging Italian Nationalism and English Letters (1940), the first half of it focused on Mazzini.

The Carlyles had become among Mazzini’s closest English friends in London by 1840, as the many references to him in their letters indicate. Mazzini described Jane Welsh Carlyle in 1844 as “the woman I value most in England,”[2] while she took pleasure in his chivalric attentions (given her husband’s more curt and curmudgeonly ways), sympathetically supported his dreams for a renovated Italy, and echoed his Italianized English phrases with great delight in her letters—phrases such as “with my soul on the pen,” “poors” for “paupers,” the “human curve” for “figure,” and allusions to the Bible as “she” (qtd. in Origo 206). Mazzini’s close personal friendship with Thomas Carlyle was increasingly marked by the wide divergence in their views, which the former man noted from the start: “two thirds of our opinions differ without any hope of my converting him or his changing me,” the Italian exile remarked in December 1839 of the Scottish writer, even though he would dine almost weekly (every Friday) at the Carlyles’s from 1840 for a period of almost eight years (qtd. in Rudman 47).

Mazzini’s essay “On the Genius and Tendency of the Writings of Thomas Carlyle,” published in The British and Foreign Review in October 1843, marked the growing breach between his ideas and Carlyle’s. As Rudman notes, while acknowledging Carlyle’s “sincerity, his spiritual emphasis and antimaterialism, his humanitarianism, artistry, and his humour,” Mazzini also denounced in the essay “Carlyle’s theory of heroes, his ready applause for mere success, and his identification of might with right” (55). Although the two remained friends, the blunt Scot in turn denounced as “rose-water imbecilities” Mazzini’s faith in the transformative power of “God and the people,” as the American transcendentalist writer Margaret Fuller noted after an evening with the Carlyles and the Italian patriot in 1846; she further reported to Ralph Waldo Emerson that “all Carlyle’s talk, that evening [was] . . . a defence of mere force,—success the test of right;—if people would not behave well, put collars round their necks;—find a hero, and let them be his slaves.”[3]

Mazzini’s devotion to the rights of the working-class “people” whom Carlyle proposed to collar for their own good led to close connections with English Chartist leaders like the engraver and author William James Linton and the self-educated political reformer William Lovett. He also mixed in London with other democrats and political refugees from the continent, among them the Polish political exiles Stanislas Worcell and Karl Stolzman. Linton described Worcell, “the chief of the Democratic party” among Polish London exiles, as Mazzini’s “closest friend” and one who had made similar sacrifices as a patriot and nationalist: a “Count of ![]() Volhynia” and “owner of large estates,” Worcell had forfeited these “on account of his prominent share in the Polish insurrection of 1830,” when he “raised a troop on his own lands, fought his way into

Volhynia” and “owner of large estates,” Worcell had forfeited these “on account of his prominent share in the Polish insurrection of 1830,” when he “raised a troop on his own lands, fought his way into ![]() Warsaw, and sat there in the Polish Senate” (Linton n. pag.).

Warsaw, and sat there in the Polish Senate” (Linton n. pag.).

In London, Mazzini won further support and admiration from members of the English middle and upper classes for his selfless work in establishing an Italian Free School in 1841 for working men and for Italian street-boys exploited as organ-grinders and street hawkers. Supporters and patrons of the school would eventually include not only Jane Carlyle, but also Lady Byron, Gabriele Rossetti, John Stuart Mill, Harriet Martineau, and Lord Ashley among others (Rudman 52). The Italian patriot’s enthusiasm for the Irish cause as well as the American anti-slavery movement and women’s rights forged additional alliances. In the words of William Lloyd Garrison, leader of the radical wing of the American abolitionist movement, in his retrospective introduction to an 1872 collection of Mazzini’s writings, not only did Mazzini strongly repudiate slavery; his “concern for the rights of man” was also “never, on any pretext, purely in a masculine sense,” given his support for the “equality of the sexes” (xvii). These views help to explain why Mazzini shone in “female society” (Mack Smith 45), and attracted passionately committed women followers such as Jessie White (later Mario) and Emilie Ashurst (later Venturi) as friends and/or disciplines.

In the eyes of others, however—particularly those in positions of power in Europe—Mazzini was a fanatical and dangerous as opposed to a visionary or “rose-water” idealist and democrat, connected through multitudinous networks with underground groups of revolutionaries in Italy and other European countries. These networks grew out of the Young Italy movement he and a group of thirty or forty others founded in ![]() Marseilles in July 1831 (Mack Smith 5). Its primary goal was to create a united republican Italy out of the conglomeration of separate states ruled by the Austrian empire and associated despotic governments under the conservative ancient regime re-established in 1815 by the Congress of Vienna. Rudman provides a vivid sketch of the “secret terroristic order” of Young Italy: its members organized into groups of the “Initiated,” their “flag the present-day Italian tricolor,” their banner emblazoned with the words, “Liberty, Equality, Humanity” on one side, while the words “Unity, Independence” flamed on the other side with the order’s symbol, “a cypress branch in memory of the martyrs of Italian liberty” (35-36). Its journal Giovine Italia, founded by Mazzini in 1832 to disseminate his vision of a free and united Italy (Griffith 78), was widely circulated, despite the dangers this entailed under a brutal regime of Austrian censorship in which Mazzini’s “own writings were banned,” as Mack Smith remarks; indeed the very “words ‘Italy,’ ‘nation,’ ‘constitutional liberty’ and even ‘railways’” were also forbidden (35).

Marseilles in July 1831 (Mack Smith 5). Its primary goal was to create a united republican Italy out of the conglomeration of separate states ruled by the Austrian empire and associated despotic governments under the conservative ancient regime re-established in 1815 by the Congress of Vienna. Rudman provides a vivid sketch of the “secret terroristic order” of Young Italy: its members organized into groups of the “Initiated,” their “flag the present-day Italian tricolor,” their banner emblazoned with the words, “Liberty, Equality, Humanity” on one side, while the words “Unity, Independence” flamed on the other side with the order’s symbol, “a cypress branch in memory of the martyrs of Italian liberty” (35-36). Its journal Giovine Italia, founded by Mazzini in 1832 to disseminate his vision of a free and united Italy (Griffith 78), was widely circulated, despite the dangers this entailed under a brutal regime of Austrian censorship in which Mazzini’s “own writings were banned,” as Mack Smith remarks; indeed the very “words ‘Italy,’ ‘nation,’ ‘constitutional liberty’ and even ‘railways’” were also forbidden (35).

By 1833, when Mazzini was involved in planning an uprising in the Italian kingdom of ![]() Piedmont-Sardinia, ruled by King Charles Albert, “Young Italy had 60,000 members,” according to Rudman (35). Rudman does not identify the source for the figure of “60,000,” and any “clandestine movement is impossible to trace in detail,” as Mack Smith remarks, but Smith also notes that Young Italy “enrolled thousands of partisans all over Italy,” as well as internationally: by the late 1830s, its newspapers “were said to have five thousand subscribers in

Piedmont-Sardinia, ruled by King Charles Albert, “Young Italy had 60,000 members,” according to Rudman (35). Rudman does not identify the source for the figure of “60,000,” and any “clandestine movement is impossible to trace in detail,” as Mack Smith remarks, but Smith also notes that Young Italy “enrolled thousands of partisans all over Italy,” as well as internationally: by the late 1830s, its newspapers “were said to have five thousand subscribers in ![]() Montevideo and

Montevideo and ![]() Buenos Aires” alone (5, 33).[4] In 1833 as well, Guiseppe Garibaldi, later to become the great guerrilla general in the battles for Italian liberation, was “enrolled” in the association and assigned to “organize a mutiny in the Piedmontese navy” (Rudman 39). The organizers of the Piedmontese coup were betrayed and twelve conspirators executed, while a hundred were imprisoned, and “hundreds” more “escaped abroad”; Mazzini himself was expelled from

Buenos Aires” alone (5, 33).[4] In 1833 as well, Guiseppe Garibaldi, later to become the great guerrilla general in the battles for Italian liberation, was “enrolled” in the association and assigned to “organize a mutiny in the Piedmontese navy” (Rudman 39). The organizers of the Piedmontese coup were betrayed and twelve conspirators executed, while a hundred were imprisoned, and “hundreds” more “escaped abroad”; Mazzini himself was expelled from ![]() France and took up residence in

France and took up residence in ![]() Switzerland, where he and a “dozen refugees from Italy,

Switzerland, where he and a “dozen refugees from Italy, ![]() Poland and

Poland and ![]() Germany” founded a “new association” named Young Europe in 1834, and where Mazzini planned another thwarted revolution in

Germany” founded a “new association” named Young Europe in 1834, and where Mazzini planned another thwarted revolution in ![]() Savoy, until he was expelled by the Swiss authorities at the close of 1836, seeking refuge in England (Mack Smith 8-9, 20). Despite his physical exile in London, however, Mazzini remained in close contact through voluminous correspondence with Italian and other European revolutionaries.

Savoy, until he was expelled by the Swiss authorities at the close of 1836, seeking refuge in England (Mack Smith 8-9, 20). Despite his physical exile in London, however, Mazzini remained in close contact through voluminous correspondence with Italian and other European revolutionaries.

Hence, as Frank J. Coppa remarks in reviewing Mack Smith’s 1994 biography of Mazzini in conjunction with Roland Sarti’s 1997 biography, “Mazzini, who was hailed by patriots as the founder of the nation, was hounded by government as an enemy of the state” (68) and it is quite possible in Sarti’s words, to arrive at “radically different interpretations of the Mazzinian legacy” (qtd. in Coppa 69). Mazzini was eyed with especial alarm by the Austrian authorities as an insurrectionary subversive—In twenty-first-century terms, a “terrorist”—who propagated his ideas and sought their transformation into action through Young Italy’s cells of “initiates.” While fear of terrorist attacks causes delays at customs today, in the mid-nineteenth century, especially in Italian states, customs officers searched “packages as if it had been thought that a Mazzini would be found in every carpet-bag,” according to one German traveler (Rudman 104). Such searches were not motiveless: in 1832, for example, Genoan custom authorities “discovered instructions for an armed resurrection hidden in the false bottom of a trunk” addressed to Mazzini’s mother (Mack Smith 7).

In one of numerous hairbreadth escapes from capture in 1857, following another failed uprising in his birthplace of ![]() Genoa, Mazzini was hidden in a mattress, almost suffocating, while his tiny, handwritten incriminating missives were hidden in the bodice of a sympathetic Englishwoman married to one of his Italian supporters, as the police inspected the house. They returned for a second inspection, but still did not find him. After an interval, Mazzini shaved off his beard and quietly left the house (Rudman 118). As Edyth Hinkley notes in narrating this incident, such hairbreadth escapes prompted the Italian poet and patriot Francesco Dall’Ongaro’s poetic derision of the authorities:

Genoa, Mazzini was hidden in a mattress, almost suffocating, while his tiny, handwritten incriminating missives were hidden in the bodice of a sympathetic Englishwoman married to one of his Italian supporters, as the police inspected the house. They returned for a second inspection, but still did not find him. After an interval, Mazzini shaved off his beard and quietly left the house (Rudman 118). As Edyth Hinkley notes in narrating this incident, such hairbreadth escapes prompted the Italian poet and patriot Francesco Dall’Ongaro’s poetic derision of the authorities:

“Where is Mazzini?” hear them cry! We answer with disdain

“Some say he is in Germany, or in England once again,

Some swear he’s inGeneva, some are certain he’s in

Spain.

Some place him on an altar, some wish him underground,

But none among his hunters know where he can be found.

Oh stupid men who seek him, once more look wildly round!

There is only one Mazzini, and can he not be found?”[5]

More often than not, Mazzini could “not be found,” although “false rumours of his being seen in Germany, Switzerland, Italy and Malta” abounded (Mack Smith 50).

Among those who wished “him underground,” Mazzini was viewed, or represented through propaganda and misinformation, as an “assassin”: for example, he was repeatedly charged with playing such a role in a case in France involving the death of two Italians, in which forged documents were used to implicate him.[6] He was also repeatedly described through his career as the “Old Man of the Mountain” (see, e.g., Rudman 37, 67, 129, 141), an Orientalist allusion that, in effect, constituted him as the Osama bin Laden of the nineteenth century in the eyes of his enemies. Antonio Bresciani’s 1854 historical romance, The Jew of Verona, is one prominent instance in which Mazzini figured as the “Old Man of the Mountains”: characterized as the “King of Assassins” because he committed no murders himself yet transformed his followers through mysterious Satanic cults into a sheaf of assassins, “fiends capable of blowing up ![]() St. Peter’s and the

St. Peter’s and the ![]() Vatican” (Rudman 129). Not surprisingly, the Vatican was among Mazzini’s most vigorous opponents; indeed, the Pope regarded the republican patriot as a “serious enemy” (Mack Smith 50). Bresciani, a Jesuit in

Vatican” (Rudman 129). Not surprisingly, the Vatican was among Mazzini’s most vigorous opponents; indeed, the Pope regarded the republican patriot as a “serious enemy” (Mack Smith 50). Bresciani, a Jesuit in ![]() Naples, wrote The Jew of Verona in the pope’s service, as the “Preface” to an 1854 edition of the romance, reprinted in an 1861 British Catholic press edition, makes clear. This preface pays tribute to Father Bresciani as a central figure in an initiative organized by Pope Pius IX to counter through propaganda the “arch-leader of the secret societies of Europe,” the wicked Mazzini, who “deceived” the people through his intoxicating “cry of liberty” and robbed Italy of her youth (Bresciani, 1861, iii-v).

Naples, wrote The Jew of Verona in the pope’s service, as the “Preface” to an 1854 edition of the romance, reprinted in an 1861 British Catholic press edition, makes clear. This preface pays tribute to Father Bresciani as a central figure in an initiative organized by Pope Pius IX to counter through propaganda the “arch-leader of the secret societies of Europe,” the wicked Mazzini, who “deceived” the people through his intoxicating “cry of liberty” and robbed Italy of her youth (Bresciani, 1861, iii-v).

Metternich notoriously dismissed Italy as no more than a “geographical expression” (Mack Smith 51) and he observed of its most passionate prophet: “I had soldiers to fight with the greatest, I succeeded in uniting emperors and kings, the Czar, the Sultan, and the Pope; but nobody on earth has given me more difficulties than a brigand of an Italian, thin, pale, shabby, yet as eloquent as the storm, as shining as an apostle, as cunning as a thief, as impudent as a comedian, as indefatigable as a lover—and his name was Joseph Mazzini!” (qtd. in Rudman 104). It is an evocative characterization of the charismatic “conspirator and revolutionist” at the heart of the political scandal in England in 1844.

The Opening of Mazzini’s Letters, Political Response, and Carlyle’s Letter to The Times

Mazzini’s close connections with English radical reformers were manifested in the presentation of the petition to the House of Commons on 14 June that initiated the Post Office scandal, which rapidly grew into a full-blown political scandal involving both the Home and Foreign Offices of the British government and fuelling debates extending to “550 pages” in Hansard (Mack Smith 42). The MP who presented the petition,[7] Thomas Slingsby Duncombe, was a radical representing ![]() Finsbury acting on behalf of Mazzini, another Italian exile Searafino Calderara, and the Chartist leaders Linton and Lovett. In the most meticulously documented historical account of the event, F. B. Smith observes that the group began to suspect secret surveillance when Mazzini passed a “letter of interest” on to Linton, and Linton pocketed it, then a couple of days later pulled it out and noted the seal had broken to reveal a double impression on it. Mazzini then instructed his friends to enclose “des grains presque invisibles” in their letters to him and further noted that the time stamps had been carefully altered to hide “a two hours’ delay in handling” (F. B. Smith 193).

Finsbury acting on behalf of Mazzini, another Italian exile Searafino Calderara, and the Chartist leaders Linton and Lovett. In the most meticulously documented historical account of the event, F. B. Smith observes that the group began to suspect secret surveillance when Mazzini passed a “letter of interest” on to Linton, and Linton pocketed it, then a couple of days later pulled it out and noted the seal had broken to reveal a double impression on it. Mazzini then instructed his friends to enclose “des grains presque invisibles” in their letters to him and further noted that the time stamps had been carefully altered to hide “a two hours’ delay in handling” (F. B. Smith 193).

Armed with proof from such sources, compiled over many weeks, Duncombe presented a petition claiming that letters sent “for no political purpose, and containing no libelous matter or treasonable comments” had been secretly detained and “their seals had been broken” by authorities of “her Majesty’s Post Office,” thus introducing “the spy system of foreign states” into a country where it was “repugnant to every principle of the British Constitution, and subversive of the public confidence, which was so essential to a commercial community” (qtd. in F.B. Smith 194).[8] While this petition was largely disregarded in the House of Commons as the expression of a few radicals, it did provoke a Times editorial (despite the generally pro-Austrian stance of the newspaper). The editorial accused the ministry involved of pursuing “a policy at once unconstitutional, un-English, and ungenerous,” by undermining the “peculiar boast of England that she is not as other countries, that her citizens are not liable to . . . the same dogging of their footsteps, opening of their letters, and prying into their cabinets as harass the subjects of continental states.” As for Mazzini, The Times dismissed him as a man whose “character and habits and society are nothing to the point. . . . He may be the most worthless and the most vicious creature in the world. But this is no reason in itself why his letters should be detained and opened” (qtd. in Rudman 61-62).

This slur on Mazzini’s character in The Times provoked Carlyle’s celebrated defence of the Italian patriot’s character in a letter dated 18 June and published the next day. Alluding to the editorial on the “disgraceful affair of Mr. Mazzini’s letters,” Carlyle unequivocally championed Mazzini the man, while also avoiding endorsement of his political opinions:

It may tend to throw farther light on this matter if I now certify you, which I in some sort feel called upon to do, that Mr. Mazzini is not unknown to various competent persons in this country; and that he is very far indeed from being contemptible—none farther, or very few of living men. I have had the honour to know Mr. Mazzini for a series of years; and, whatever I may think of his practical insight and skill in worldly affairs, I can with great freedom testify to all men that he, if I have ever seen one such, is a man of genius and virtue, a man of sterling veracity, humanity, and nobleness of mind, one of those rare men, numerable unfortunately but as units in this world, who are worthy to be called martyr-souls; who, in silence, piously in their daily life, understand and practise what is meant by that. Of Italian democracies and young Italy’s sorrows, of extraneous Austrian Emperors in Milan, or poor old chimerical Popes in

Bologna, I know nothing, and desire to know nothing; but this other thing I do know, and can here declare publicly to be a fact, which fact all of us that have occasion to comment on Mr. Mazzini and his affairs may do well to take along with us, as a thing leading towards new clearness, and not towards new additional darkness, regarding him and them.

Whether the extraneous Austrian Emperor and miserable old chimera of a Pope shall maintain themselves in Italy, or be obliged to decamp from Italy, is not a question in the least vital to Englishmen. But it is a question vital to us that sealed letters in an English post-office be, as we all fancied they were, respected as things sacred; that opening of men’s letters, a practice near of kin to picking men’s pockets, and to other still viler and far fataler forms of scoundrelism, be not resorted to in England, except in cases of the very last extremity. When some new Gunpowder Plot may be in the wind, some double-dyed high treason, or imminent national wreck not avoidable otherwise, then let us open letters: not till then. To all Austrian Kaisers and such like, in their time of trouble, let us answer, as our fathers from of old have answered:—Not by such means is help here for you. Such means, allied to picking of pockets and viler forms of scoundrelism, are not permitted in this country for your behoof. The right hon. Secretary does himself detest such, and even is afraid to employ them. He dare not: it would be dangerous for him! All British men that might chance to come in view of such a transaction, would incline to spurn it, and trample on it, and indignantly ask him, what he meant by it! (The Carlyle Letters Online).

As Carlyle’s letter makes very clear, he had little concern for “Austrian Kaisers” or the struggle for “Italian democracies” and “young Italy’s sorrows.” What chiefly motivated his sense of outrage, aside from the attack on his friend, was the violation of a British citizen’s “sacred” right to preserve the privacy of “sealed letters in an English post-office.”

The controversy escalated when a second petition was presented by Duncombe on 24 June on behalf of the Polish revolutionary exile Charles Stolzman. Duncombe now pointed out that “60-70 letters to Mazzini from 25-30 different people had been opened,” all under a single warrant, when the law required a warrant for each letter. Moreover, the time-stamps on the letters had been altered to conceal the surveillance, which at the time technically constituted an act of “forgery,” punishable by transportation. Some Liberal (Whig) M.P.s now joined radical M.P.s in calling for an inquiry, as Richard Sheil, the Irish orator, “brilliantly” argued “that the British nation was degraded by playing eavesdropper” for “Austrian and Russian despotism.” The eminent Whig Thomas Babington Macaulay “demanded to be told how Graham had used” his “‘abhorrent’” power of issuing warrants for opening letters and Lord John Russell supported Macaulay, even though in power he himself had exercised the prerogative of issuing warrants for opening letters (F. B. Smith 195, 193).

On 2 July, the scandal took on a more ethically fraught and international dimension, as Duncombe presented evidence to the Commons that Mazzini’s opened letters had included one dated 1 May from the Italian nationalist Emilio Bandiera, and that Britain authorities had shared information from Bandiera’s letter with Austrian authorities, leading to the arrest of “56-60 Italians now in Austrian dungeons” (F. B. Smith 196), where political prisoners were routinely tortured and executed without any due process. A postscript in a letter written by Thomas Carlyle on 1 July to Jane, then in ![]() Scotland, conveys the consternation this conjunction of events caused: “There is still a great talk and excitement about the Letter business. A new debate, as I told you, is expected to come on about it tomorrow night.” In the same postscript, Carlyle alluded to talk among the Carlyles’ London friends of the landing of “200 men” in

Scotland, conveys the consternation this conjunction of events caused: “There is still a great talk and excitement about the Letter business. A new debate, as I told you, is expected to come on about it tomorrow night.” In the same postscript, Carlyle alluded to talk among the Carlyles’ London friends of the landing of “200 men” in ![]() Calabria in the south of Italy (The Carlyle Letters Online).

Calabria in the south of Italy (The Carlyle Letters Online).

This revelation brought the Earl of Aberdeen, the Foreign Secretary, into the scandal more directly: in fact, some accounts suggest that it was at the “prompting” of Aberdeen that Graham acted, to use Rudman’s terms (58), in a chapter of Italian Nationalism and English Letters he titles “Lord Aberdeen Spies on Mazzini’s Letters.” One of Mazzini’s later English disciples, Jessie White Mario, is another who emphasizes that “[a]s a matter of fact, it was Lord Aberdeen who had had the letters opened and who had . . . transmitted their contents to the Austrian ambassador” (68). F. B. Smith’s research into Graham’s papers makes it clear, however, that it was Graham and not Aberdeen who was primarily responsible for having “instigated the espionage,” growing out of his relationship with Baron Philipp von Neumann, “the Austrian ambassador in London,” and “ a tough, foxy reactionary” (189). In fact, F. B. Smith concludes that Graham “engaged in a dubious transaction with a foreign representative of a rather unpopular power without consulting his Prime Minister or Cabinet colleagues” (194).

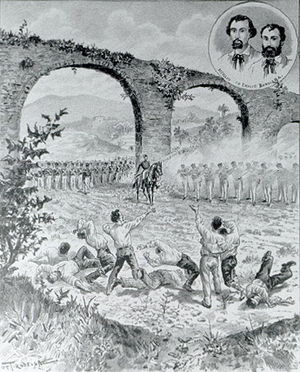

However one apportions ministerial responsibility, the end result was that the British Home Office not only stood charged with breaking the seals and secretly reading the contents of Mazzini’s private letters, passing on the information to the Foreign Office; the government was now also widely accused of collusion with the Austrian empire and the affiliated despotic Neapolitan government. This collusion would take on a more sinister cast through the summer of 1844, as news of the betrayal and execution of Emilio Bandiera and his brother Attilio and associates filtered back to England. The Attilio brothers were young Venetian noblemen and officers in the Austrian navy inspired by “reading one of Mazzini’s newspapers” to “start an insurrection in Naples and the Papal States” that might spread to the rest of “Austrian-controlled territory” in Italy, despite Mazzini’s own attempts to dissuade them from such a venture (Mack Smith 41). Betrayed by some co-conspirators, they deserted ship and fled toHistorians disagree on the extent to which the British spying on Mazzini directly contributed to the fate of the Bandiera brothers and their supporters, since the Austrian authorities also drew on secret informants closer to the Italian revolutionaries. Rudman follows many nineteenth-century sources in stating that the English government had “blood on its hands” (58).[9] G. M. Trevelyan, in a letter to The Times in 1907, cited evidence to support this view in a letter written by the Pope’s Minister, Cardinal Lambruschini, dated 12 April 1844.[10] The posthumously published memoir of the Mazzinian disciple Jessie White Mario, however, pointed out that State Archives in Milan revealed that Austria had “obtained earlier and independent knowledge of the plans of the Venetian patriots” (Mario 68). Mack Smith concludes, nevertheless, that “[s]ome degree of responsibility lay with the British government,” responding in part to Metternich’s fabrication of stories that Mazzini was involved in a plot to assassinate the Piedmont king Charles Albert (41). In contrast, F. B. Smith observes that “information from the British authorities” gleaned from spying on Mazzini’s correspondence with Emilio Bandiera (followed up by torture) “probably swelled the Austrians’ list” of Italians they imprisoned or executed,” but that “it seems likely that the British side was innocent” in directly influencing the betrayal of the Bandiera brothers, given the role of a Corsican “agent provocateur” among their closest associates (196, 199-200).

In early July, however, even before the story of the Bandiera brothers was concluded or fully known in England, Duncombe’s accusations in the House of Commons that British Ministers had supplied the names of the Bandiera brothers’ supporters to the Austrians, following on the scandal of the letter-opening itself, was enough to light “‘up a flame throughout the country,’” in the words of one Tory Minister (qtd. in F. B. Smith 197). To defuse the situation, the Tory Ministers agreed to an inquiry, but ensured that its proceedings remained secret, packed it with “fuddy-duddy antiquarians and country members unlikely to sympathize with Mazzini,” and directed it to investigate the “law and history” of state letter-opening espionage, not the case of the petitioners (F.B. Smith 197; see also Vincent 9). The Times sardonically reported on 4 July of Graham that “he has not only secured . . . a private trial, but he has chosen his own jury” (qtd. in Carlyle Letters Online 1n).[11] Another committee was established in the House of Lords, where Lord Aberdeen and Lord Wellington both denied that any information from Mazzini’s letters had been communicated to any foreign powers. The upshot was “two of the most mindless, evasive compilations ever to issue from the British Parliament”—underscoring, however, a long tradition of “opening the mail of foreign embassies” as well as the mail of British citizens regarded as threats, including, most recently, Chartist leaders (F. B. Smith 198-99).[12]

Punch Parodies and “Anti-Graham” Envelopes and Seals

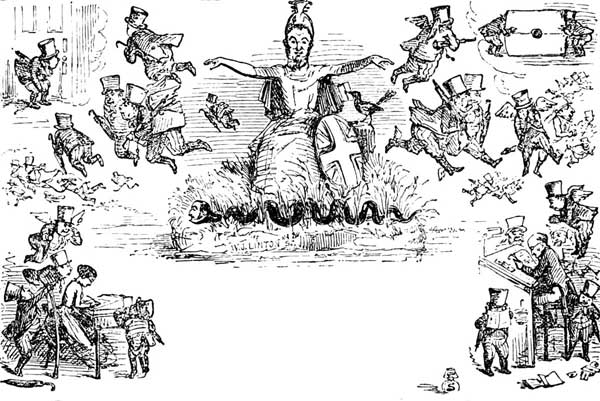

While these secret inquiries in the House of Commons and House of Lords were engaged in their strategically evasive exercises, Sir James Graham in particular was being pilloried by the press, with an emphasis falling, as in Carlyle’s letter to The Times, on the violation of privacy that the opening of letters entailed. On 4 July, Thomas Carlyle wrote to “Dear Goody” Jane who was in Scotland, sending her a copy of The Times reporting on the most recent parliamentary debates and remarking on Graham’s “humiliation,” that it might satisfy Mazzini himself “to observe the whine he gives, like a lashed hound” (Carlyle Letters Online). The scandal by now had gone “viral,” in 21st-century terms, as is evident from the pages of Punch, described by M. H. Spielmann in his entertaining history of the periodical.

To begin with, a cartoon on 2 July depicted Graham as “Paul Pry at the Post Office” peering into peoples’ letters, alluding to a character in a popular farce, an interfering busybody in a top-hat; the “Paul Pry” characterization was then echoed in many other journals (Spielmann 114). In the weeks that followed, Punch also printed the contents of Graham’s “imaginary letters (which it pretended to have acquired by espionage)” (Rudman 59), nicknamed him “Fouché,” after Joseph Fouché, the notorious French Minister of Police famous for his system of spies, and in one among several additional cartoons and squibs, featured Graham conducting a military-style review of the London postmen:

Present letters!

Feel for seal!

Thumb on seal!

Open letters!

Read letters!

Re-fold letters!

Re-seal letters!

Pocket letters!” (qtd. in Rudman 59)

Punch’s most memorable salvo, apart from attaching the moniker of “Paul Pry” to Graham—an “image that haunted him ever after” (F. B. Smith 198)—was the “Anti-Graham Envelope” and the associated Anti-Graham “Wafers”—“the latter extra strongly gummed,” as Spielmann notes (114). He further notes that the envelope’s design was “drawn by John Leech” and “afterwards appropriately engraved by Mr. W. J. Linton, whose share in the agitation was a considerable one,” adding that the “circulation attained by this envelope was very wide”—although he could not ascertain “if it was ever actually sent through the “General Post Office” (114). The Leech design featured Britannia in the centre, with a snake bearing Graham’s head crawling at her feet, and various images of Paul Pry in his characteristic top hat flitting about these central figures. Other publishers soon followed suit with “envelopes in the shape of padlocks” with “Not to be Grahamed” on them (Spielmann 115).

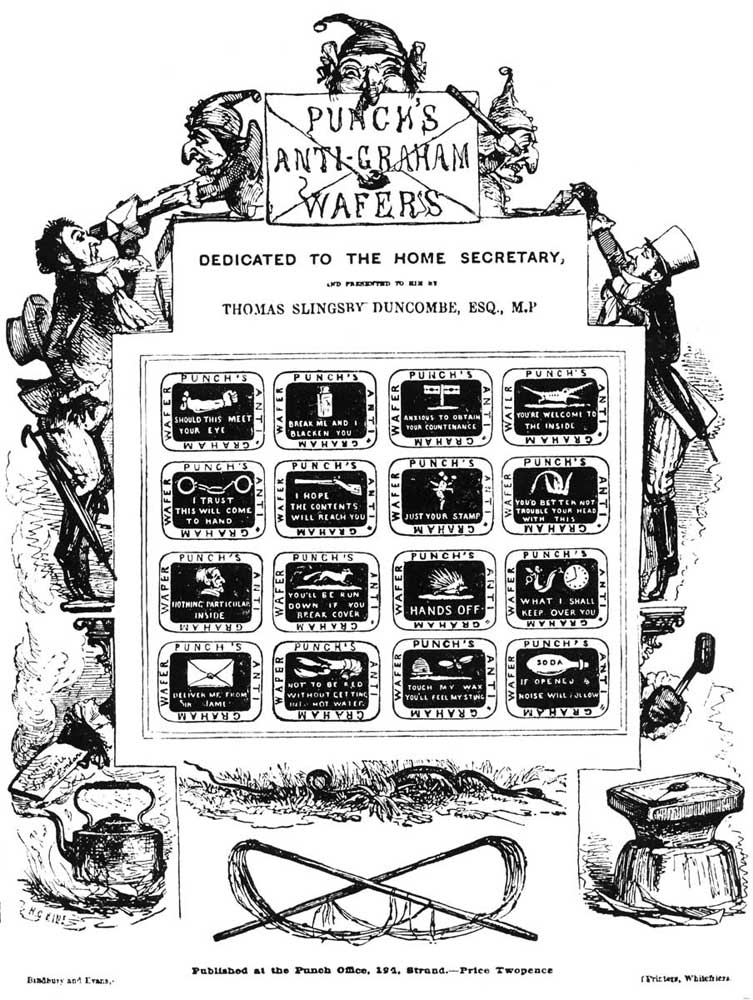

The “Anti-Graham Wafers” (alluding to the stamp-like gummed wafers widely used in the period when adhesive envelopes were still rare and sealing wax was expensive) were published, “on the clever initiation of Henry Mayhew,” in a “sheet, 10 inches by 7¾ inches in size, drawn by H. G. Hine,” with “sixteen wafers, in green ink, in the midst of a witty design, in brown, that bore the devices of a snake in the grass, a cat-o’-nine-tails, a kettle steaming the fastening of a letter, and other suggestive personalities. These were supposed to be cut up and used as wafers on envelopes, and that they were so used is probable, in view of their extreme rarity at the present day” (Spielmann 115). The wafers were “Dedicated to the Home Secretary” and feature various witticisms and motifs. For example, a blacking bottle appears over the caption, “BREAK ME AND I BLACKEN YOU”; another features a bared arm and fist over the caption, “SHOULD THIS MEET YOUR EYE”; another a fox, “YOU’LL BE RUN DOWN IF YOU BREAK COVER”; others present a bristling hedgehog over the caption, “HANDS OFF,” and a crocodile with a wide open jaw over “YOU’RE WELCOME TO THE INSIDE.”

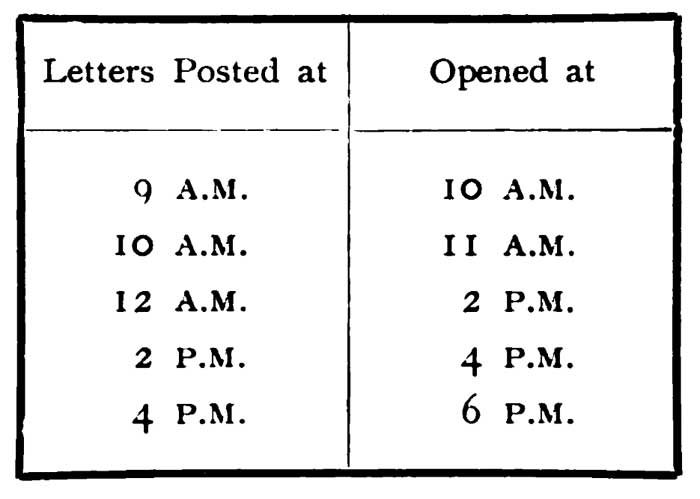

The cartoons and mock notices in Punch continued through the summer into the fall of 1844, among them “The Post Office Peep-Show, a Penny a Peep,” in which “foreign sovereigns, on paying their money to Showman Graham, are permitted to violate the secrecy of British correspondence.” Another notice informed “Continental clients” that “‘on and after the present month the following alterations will take place in the opening of letters’” (Spielmann 116). (See Fig. 6.)

A ![]() British Postal Museum and Archive catalogue description of a collection of “Anti-Graham” clippings from Punch discovered in 2005 (“Newspaper Cuttings from Punch”) provides a useful index of these anti-Graham squibs in the popular periodical. If Graham was now notorious as “Paul Pry,” Mazzini was transformed by the scandal into a celebrity, one of a “select group of foreigners” to be “adopted as British household gods” (F. B. Smith 202). Effigies of him were sold by “the thousand” (Mack Smith 43).

British Postal Museum and Archive catalogue description of a collection of “Anti-Graham” clippings from Punch discovered in 2005 (“Newspaper Cuttings from Punch”) provides a useful index of these anti-Graham squibs in the popular periodical. If Graham was now notorious as “Paul Pry,” Mazzini was transformed by the scandal into a celebrity, one of a “select group of foreigners” to be “adopted as British household gods” (F. B. Smith 202). Effigies of him were sold by “the thousand” (Mack Smith 43).

Nevertheless, Graham and the government were not without their supporters, and Mazzini was not without harsh critics in England, even at this high point in his positive reputation as a political exile in England. Maurizio Masetti’s analysis of coverage of the Post Office scandal demonstrates that Tory papers like The Morning Herald and, after the initial furor over letter-opening, even The Times defended taking “action on matters of national security” (Masetti, “The 1844 Post Office Scandal” 206). The Morning Herald advocated that Mazzini be expelled from Britain, ceasing “‘to make this country the focus of all European conspiracies . . . in return for our hospitality’” (qtd. in Masetti 212), and even “more liberal papers turned their back” on Mazzini’s “expectations of support” (Masetti 211). As for Mazzini’s radical friends, a letter to The Morning Herald denounced Duncombe as “a cur . . . employed by the Chartists and other malcontents to grub for grievances, in order to pamper their diseased appetite for declaiming against the established order of government’” (qtd. in Masetti 208).

Literary Impact and Further Political Ramifications: Chartist and Risorgimento Networks

The scandal occasioned by the discovery of British authorities spying upon Mazzini’s private letters had a notable impact on support for the Italian cause in England and on English literature of the period, as well as a number of immediate and more lasting political consequences. Numerous scholars—including Rudman, G. M. Trevelyan, Robert Viscusi, Matthew Reynolds, Maura O’Connor, Alison Chapman and Jane Stabler—have demonstrated that the English in the nineteenth century had long had a romanticized fascination with Italy. In fact, Viscusi presents a witty send-up of “four huge English Italies”: Chaucer’s Italy, “the Protestant’s Italy of Spenser and Shakespeare and Webster and Milton,” the neoclassical “Imperialist’s Italy of Addison and Gibbon” in which “[d]ead bureaucrats in bedsheets ennoble a landscape,” and the “Romantic Italy of Byron, Shelley, and Samuel Rogers,” “the graveyard of Keats and Shelley,” in which “[e]verywhere one encounters Alps, storms, deathbeds” (246). The Romantic English fascination with Italy that Germaine De Staël’s Corinne (see Erik Simpson, “On Corinne, Or Italy”) and Byron’s Childe Harold enhanced is reflected in Rogers’ poetical two-part Italy (1822, 1828)—re-issued in a lavishly illustrated edition of 10,000 copies with engravings by Turner and other artists in 1830; 6,800 copies of his illustrated Italy (which cost ₤7,335 to produce) had been sold by May, 1832, with continuing sales after that more than recouping the costs of production (Clayden 2.4).

The letter-opening scandal intensified this Italomania, but shifted it away from a touristic focus on Italy as a land of past artistic glories towards an engagement with modern Italian nation-building. Mazzini himself seized the occasion to popularize the Italian cause, publishing an anonymous article, “Mazzini and the Ethics of Politicians,” in the Westminster Review in September 1844, and a pamphlet in May 1845. Titled, Italy, Austria, and the Pope: A Letter to Sir James Graham, the pamphlet detailed the despotic repression and censorship of print materials as well as moustaches (associated with liberalism) in Italy, where the Austrian catechism for Italian children in asylums and schools explicitly instructed them to “behave like slaves” because “the Sovereign is their master and his power extends over their property, as over their persons” (qtd. in Rudman 65, 67-68). As O’Connor suggests, the letter-opening scandal led “middle-class men and women” to “embrace a more cosmopolitan liberalism” in relation to Italy (65). Given Mazzini’s close connections with Chartist leaders, it also developed support for Italy among working-class activists, subsequently reflected in Mazzini’s sequence of articles, “Thoughts on Democracy in Europe” in The People’s Journal from August 1846 to April 1847 and his dissemination of his ideas through the “The People’s International League,” founded on 28 April 1847 to aid the people of Britain “in forming a correct judgment of the national questions now agitating Europe” (Claeys 229-30; see also Rudman 76-77).

One of the most important outcomes of the letter-opening incident for Mazzini was the friendships to which it led with a widening circle of prominent English politicians, families, and literary figures, including reformist thinkers and/or future MPs such Peter Taylor, Joseph Cowen, and William Shaen, and James Stansfield, MP, as well as Stanfield’s influential father-in-law, the radical William Henry Ashurst, supporter of progressive causes from the penny post to the American anti-slavery movement to Italian liberation, and leader of what became known as the “Muswell-Hill” brigade (named after Ashurst’s residence). The alliance the scandal brought about with the Ashurst family was particularly important: by 1846, members of the clan, including four free-thinking daughters—one of whom, Emilie, would become Mazzini’s later translator and biographer—were familiarly terming the Italian patriot “Mazz” or the “Angel” (Rudman 73-74). The Ashursts were also increasingly displacing the Carlyles, and Jane Welsh Carlyle in particular, among Mazzini’s closest friends. Some of these figures (William Ashurst, Taylor) were members along with W. J. Fox, Joseph Toynbee, and others of the People’s International League. Several of them went on to act as influential members of the Society of the Friends of Italy established by Mazzini in February and March 1851.[13]

Between the letter-opening scandal and the formation of this society came the brief glory of the Roman Republic of 1849, when Mazzini for a brief period was one of three Triumvars and his dreams of a liberated Italy seemed about to be realized, before Louis Napoleon of France sided with the Pope and the established political order and the Republic was defeated. This dramatic translation of Mazzinian thought into action further increased the Italian patriot’s celebrity status on his return to England. The failure of democratic uprisings and nationalist revolutions in other European states in 1847-49 brought “thousands” of exiles from the continent to England along with Mazzini, as “London witnessed an influx of Poles, Frenchmen, Hungarians, Germans, and Italians in particular” (Claeys 226-27).

Before this development, however, the letter-opening scandal brought Mazzini to the attention of Charles Dickens and Robert Browning in 1844-46, among other English writers. Dickens had characterized Carlyle’s letter to The Times as “noble” (qtd. Rudman 66) and expressed anti-Graham sentiments at the time of the incident, writing a letter to Thomas Beard on 28 June 1844 in which he wrote on the envelope flap, “It is particularly requested that if Sir James Graham should open this, he will not trouble himself to seal it [agai]n” (Letters 4.151). In February 1846, the case of a swindler using Mazzini’s name to beg money from Dickens brought the novelist and patriot together and in 1847 Dickens attached himself to the People’s International League as a “member of its Council” (Rudman 72, 78).

In Browning’s case, Mazzini is widely assumed to be the chief model for the exiled Italian patriot the poet somewhat sympathetically depicts in “Italy in England” (later retitled “The Italian in England”), published 6 November 1845 in Dramatic Romances and Lyrics. The dramatic monologue portrays an exiled Italian patriot recalling his experience of hiding beneath an aqueduct in ![]() Lombardy, “hounded” by the Austrians, with a ransom on his head. Betrayed by one of his closest friends, he is saved by a young Italian “sister” in patriotism, symbolically associated with mother Italy herself. Browning evidently sent a copy of his pamphlet to Mazzini with apologies for not taking part in celebrations for the fourth anniversary of the Italian patriot’s Free Italian School on 11 November (Masetti, “Lost in Translation” 19). The poem prompted a letter from Mazzini to Browning dated 13 November in which he congratulated him, observed of “Italy in England” that he had “read, re-read,” and read it to his friends, and spoke of the “pleasure” its author gave him “as a man and a poet.” Arguably, however, the poem is less sympathetic to the Italian cause than Mazzini assumed, in casting the nameless exile it depicts as a somewhat vindictive and bloodthirsty patriot. At this time, Mazzini also sent Browning a copy of his 1844 pamphlet on the Bandiera brothers, Ricordi dei fratelli Bandiera et dei loro compagni de martirio in Consenza, published in

Lombardy, “hounded” by the Austrians, with a ransom on his head. Betrayed by one of his closest friends, he is saved by a young Italian “sister” in patriotism, symbolically associated with mother Italy herself. Browning evidently sent a copy of his pamphlet to Mazzini with apologies for not taking part in celebrations for the fourth anniversary of the Italian patriot’s Free Italian School on 11 November (Masetti, “Lost in Translation” 19). The poem prompted a letter from Mazzini to Browning dated 13 November in which he congratulated him, observed of “Italy in England” that he had “read, re-read,” and read it to his friends, and spoke of the “pleasure” its author gave him “as a man and a poet.” Arguably, however, the poem is less sympathetic to the Italian cause than Mazzini assumed, in casting the nameless exile it depicts as a somewhat vindictive and bloodthirsty patriot. At this time, Mazzini also sent Browning a copy of his 1844 pamphlet on the Bandiera brothers, Ricordi dei fratelli Bandiera et dei loro compagni de martirio in Consenza, published in ![]() Paris in 1844. He furthermore mentioned his more recent pamphlet on Italy, Austria, and the Pope, and he sought to recruit the English poet as an advocate for Italian nationalism, remarking, “There has been a need in England to note our condition and our cause; and men like you can best spread the sympathy we are looking for” (The Brownings’ Correspondence 11: 169-70).

Paris in 1844. He furthermore mentioned his more recent pamphlet on Italy, Austria, and the Pope, and he sought to recruit the English poet as an advocate for Italian nationalism, remarking, “There has been a need in England to note our condition and our cause; and men like you can best spread the sympathy we are looking for” (The Brownings’ Correspondence 11: 169-70).

While Browning was wary of writing directly in support of political causes, for a period at least, Mazzini found a more sympathetic supporter in Elizabeth Barrett Browning, whose two-volume collection Poems (1844), published under her maiden name, “Elizabeth Barrett Barrett,” had established her transatlantic reputation as a leading poet of the age. On 9 April 1845, EBB referred to the “letter question ‘in re Mazzini’” as one of England’s “disgraces through Europe” (The Brownings’ Correspondence 10.153). Her interest in Italy and some knowledge of Mazzini predated the courtship period and her marriage to Browning in September 1846, and residence in Italy. As Margaret Morlier has shown, her two famous sonnets addressed to George Sand in her 1844 collection echo but also resist remarks in Mazzini’s 1839 essay on George Sand in The Morning Chronicle,[14] while her intense fascination with Italy in the early 1840s is reflected in the long fragment “Italy! World’s Italy!”[15] The Anglocentric and aesthetic interest in Italy chiefly as the graveyard of Keats and Shelley in this unfinished work is replaced in Casa Guidi Windows (1851) by a much more direct engagement with Risorgimento politics: specifically, the 1847-48 uprisings in Tuscany. Part Two of the poem includes three extended apostrophes invoking Mazzini as a leader and teacher, while also counseling him to avoid connection with the violence of “dagger’s heft” and saluting him somewhat equivocally as an “extreme theorist.”[16] Mazzini responded in part by recommending Casa Guidi Windows as well as Robert Browning’s poetry to Italian contacts such as Francesco Crispi eager to learn more about English thought (Rudman 113).

The Brownings both grew much more critical of Mazzini in the late 1850s and early 1860s, in part because, like one of their closest associates in this period, Isa Blagden in her novel Agnes Tremorne (1861), they increasingly associated him with assassination attempts (Rudman 129). Most notably, the Italian patriot came to be linked (unjustifiably, historical evidence now indicates) through the manipulations of his enemies and the distortions of the press with another Italian exile, Felice Orsini, who attempted to assassinate Emperor Napoleon III of France in 1858 using bombs made in ![]() Birmingham. After this incident, the Brownings—already skeptical of Mazzini—transferred their support to Count Camillo Cavour of Piedmont, as the leader of the movement to liberate and unify Italy. Ironically, however, as Mack Smith points out, in fact “Mazzini deplored Orsini’s attempt,” and it was Cavour who had close connections with the would-be assassin, knowing that he was an enemy of Mazzini’s: indeed, Cavour “paid a pension to Orsini’s widow” from his “secret service funds” (122). Nevertheless, it was Mazzini who was publicly tarred by Orsini’s actions, which also resulted in Lord Palmerston’s unsuccessful attempt, under French pressure, to pass a Conspiracy Bill for the extradition of political refugees from Britain, a country increasingly viewed as a “refuge of radicals” at this time (Rudman 123,115).

Birmingham. After this incident, the Brownings—already skeptical of Mazzini—transferred their support to Count Camillo Cavour of Piedmont, as the leader of the movement to liberate and unify Italy. Ironically, however, as Mack Smith points out, in fact “Mazzini deplored Orsini’s attempt,” and it was Cavour who had close connections with the would-be assassin, knowing that he was an enemy of Mazzini’s: indeed, Cavour “paid a pension to Orsini’s widow” from his “secret service funds” (122). Nevertheless, it was Mazzini who was publicly tarred by Orsini’s actions, which also resulted in Lord Palmerston’s unsuccessful attempt, under French pressure, to pass a Conspiracy Bill for the extradition of political refugees from Britain, a country increasingly viewed as a “refuge of radicals” at this time (Rudman 123,115).

Other English authors whose works were influenced, directly or indirectly, by Mazzini and the letter-opening scandal include Arthur Hugh Clough, George Eliot, George Meredith, Algernon Charles Swinburne, and Benjamin Disraeli. The short-lived Roman Republic forms the backdrop for Arthur Hugh Clough’s characteristically ironic epistolary novel-in-verse, Amours de Voyage,which he began writing in ![]() Rome in 1849 but did not publish until 1858. Clough, however, hardly portrays the revolutionaries as heroic, even though, after paying a visit to Mazzini in Rome on 22 April, he found the Italian nationalist “a less fanatical fixed-idea sort of man” than he had “expected” (Phelan 75). In Eliot’s case, as Andrew Thompson points out, George Henry Lewes, co-editor of The Leader, was a member of the Society of the Friends of Italy, forming a direct conduit for the famous novelist’s knowledge of Mazzini. Moreover, the MP Peter Taylor, one of the Italian patriot’s “personal friends,” also became a close friend of Eliot’s. One delayed result of these connections was Eliot’s portrait of the eponymous hero of Daniel Deronda as a Jewish prophetic nationalist who rediscovers his Jewish identity in Mazzini’s native city of Genoa, as Thompson notes (104), even though after mid-century, Eliot would increasingly distance herself from Mazzini, like the Brownings and other middle-class English men and women.

Rome in 1849 but did not publish until 1858. Clough, however, hardly portrays the revolutionaries as heroic, even though, after paying a visit to Mazzini in Rome on 22 April, he found the Italian nationalist “a less fanatical fixed-idea sort of man” than he had “expected” (Phelan 75). In Eliot’s case, as Andrew Thompson points out, George Henry Lewes, co-editor of The Leader, was a member of the Society of the Friends of Italy, forming a direct conduit for the famous novelist’s knowledge of Mazzini. Moreover, the MP Peter Taylor, one of the Italian patriot’s “personal friends,” also became a close friend of Eliot’s. One delayed result of these connections was Eliot’s portrait of the eponymous hero of Daniel Deronda as a Jewish prophetic nationalist who rediscovers his Jewish identity in Mazzini’s native city of Genoa, as Thompson notes (104), even though after mid-century, Eliot would increasingly distance herself from Mazzini, like the Brownings and other middle-class English men and women.

A more explicit and positive portrait of Mazzini appears in George Meredith’s Vittoria, first published in The Fortnightly Review in 1866, where Meredith presents a nuanced portrait of Mazzini as the “Chief” that Rudman describes as “the high-water mark of Mazzini’s influence on English letters”; as Rudman further notes, Meredith was “possibly first drawn” to Mazzini by “reading Carlyle’s defence of the Italian patriot” in The Times (139, 66; see also Huzzard). By 1857, as well, Mazzini had gained the young Swinburne as one of his most enthusiastic disciples, in part through the publications of the Society of the Friends of Italy. While works such as the “Ode to Mazzini,” dating from 1857, remained unpublished (Rudman 119), Mazzini’s influence later left its mark throughout Swinburne’s Songs before Sunrise in 1871. By this period, however, Mazzini and the cause he represented was waning. Hence, in Disraeli’s best-selling religious and political romance Lothair, he appears “thinly veiled under the guise of Mirandola,” as an aging and somewhat fanatical writer of “fiery pamphlets” (Rudman 153).

Disraeli had been directly involved in the political debates of 1844 over the opening of Mazzini’s letters, which opened the way for the “split” in the Tory party over the protectionism and the repeal of the Corn Laws in 1846. F. B. Smith points out that Disraeli’s response to the attacks on Graham during this scandal foreshadowed the role he would later play in this pivotal split, as he parted ways with the Tory Prime Minister Sir Robert Peel and both Graham and Lord Aberdeen. Indeed, Disraeli’s “famous phrase about [Tory] Ministers stealing Whigs’ clothes, commonly quoted in connection with the Corn Law debates, occurs in a debate on letter opening in 1845” (F. B. Smith 202). The Tory split in the mid-1840s was thus one of the key political developments shaped by the scandal.

Other important political consequences, aside from English support for Italian liberation and unification, included a relatively restrained policy regarding state surveillance of private letters that prevailed in England until the Irish troubles of the 1880s (F. B. Smith, 202). “[T]he ‘Secret’ branch of the Post Office (dealing with foreign letters)” was abolished in August 1844, as Porter notes, citing a remark by Sir Rowland Hill, “chief secretary of the Post Office from 1846 to 1864,” that the Office “never thereafter used its letter-opening powers ‘except in a very few cases’” (78). John W. M. Chapman similarly observes that “the whole apparatus of the Secret Office and the Private Office of the Postmaster-General was virtually dismantled” after the affair of Mazzini’s letter-opening, although “[i]n practice, . . . especially during the Crimean War,” and in colonial contexts such as ![]() India, British state espionage continued, even though the “domestic mails in Britain were treated with the greatest circumspection by the postal authorities after 1845.” Although the Secretary of State continued to hold the power to “authorize by warrant the Postmaster-General to open letters,” the “important principle was established by Mazzini and the Carlyles and their friends that the payment of the penny post should signify the agreement of the citizen that the cost borne by them was solely for the transport of their communications and was not a license for the state to take ownership of these communications” (Chapman n. pag.). Such developments, however, by no means brought an end to the culture of state secrecy and surveillance in Britain, as David Vincent emphasizes (see below).

India, British state espionage continued, even though the “domestic mails in Britain were treated with the greatest circumspection by the postal authorities after 1845.” Although the Secretary of State continued to hold the power to “authorize by warrant the Postmaster-General to open letters,” the “important principle was established by Mazzini and the Carlyles and their friends that the payment of the penny post should signify the agreement of the citizen that the cost borne by them was solely for the transport of their communications and was not a license for the state to take ownership of these communications” (Chapman n. pag.). Such developments, however, by no means brought an end to the culture of state secrecy and surveillance in Britain, as David Vincent emphasizes (see below).

As the century drew toward a close, the affair of Mazzini’s letters was narrated many times, by historians, biographers, political reformers and the Italian patriot’s disciples. Linton and Lovett, the Chartist reformers, both included the story in the memoirs they later published, as did Jessie White Mario, Mazzini’s disciple and political activist, in her posthumously published memoirs of the Italian Risorgimento. Emilie Ashurst Venturi was early in the field with publication of Joseph Mazzini: A Memoir, prefaced by the words, “Dedicated to the Working Classes by P. A. Taylor M.P.” and a preface by Taylor disputing the “vulgar conception” of Mazzini as “a mere Utopian: a dreamer of dreams,” and urging readers “to prolong the echo of his noble thoughts—to repeat the story of his noble life” (Venturi vi). Venturi chose to retell the story of the Post Office scandal largely through Mazzini’s own words and reflections on the connections between monarchical and despotic governments and the evils of state espionage, including his remark, italicized for emphasis, that these would only end when “the government of the State should be carried on precisely as men manage their private affairs, by entrusting them to men of intelligence and probity in whatever sphere they find those qualities united” (qtd. in Venturi, 66).

Twenty-First Century Resonances: The Arar Affair, WikiLeaks, and Phone Hacking

Quite apart from its historical importance, the opening of Mazzini’s letters remains resonant in the context of 21st-century debates over the powers of the state to engage in secret surveillance of citizens and communications as well as citizens’ rights to privacy. David Vincent chooses this event as the moment when state secrecy became “modern” in his 1998 study of the British political “culture of secrecy.” “In the beginning were poppy seeds and grains of sand,” Vincent remarks in his opening sentence (1), alluding to the implanted particles used to verify the suspicion of Mazzini and his friends that his mail was being secretly intercepted. Vincent argues that, while the 1844 scandal did result in a “quarter of a century” in Britain when the government “largely refrained from the surveillance of the thoughts and actions of its citizens,” “the Mazzini affair, and the debate which surrounded it, represented not the end but the beginning of a tradition of public secrecy whose effects were more profound and pervasive than the specific matter of opening letters” (2). Given the secret transmission of information from the British authorities to the Austrian ambassador in London and thus, ultimately, to Mazzini’s arch-enemy Metternich, the spying on Mazzini also raised the spectre, like state espionage in democratic countries in our time, of collusion between governments that ostensibly support civil rights and despotic regimes that violate such rights. This spectre is all the more haunting in the wake of the enhancement of state surveillance and the securitizing discourse of the USA Patriot Act of 26 October 2001, the UK Anti-terrorism, Crime and Security Act of December, 2001, and the Canadian Anti-Terrorism Act of 24 December 2001 in response to 9/11.

The North American Maher Arar case of 2002-3—a notorious instance of “extraordinary rendition” facilitated by new anti-terrorism regimes in ![]() Canada and the United States—exhibits some suggestive parallels with the Mazzini affair, especially if one considers the role of the Canadian government in sharing information (along with serious misinformation) with governments engaged in humans rights abuses at differing levels. Arar, an engineer and wireless technology consultant with dual Canadian and Syrian citizenship, was arrested in

Canada and the United States—exhibits some suggestive parallels with the Mazzini affair, especially if one considers the role of the Canadian government in sharing information (along with serious misinformation) with governments engaged in humans rights abuses at differing levels. Arar, an engineer and wireless technology consultant with dual Canadian and Syrian citizenship, was arrested in ![]() New York at

New York at ![]() JFK Airport in September 2002 by the US Immigration and Naturalization Service, acting upon secret information provided by the Canadian Royal Canadian Mounted Police (RCMP) and the Canadian Security Intelligence Service (CSIS). On the basis of this and other information, the Canadian engineer was detained without charges for two weeks, denied access to a lawyer, and deported to

JFK Airport in September 2002 by the US Immigration and Naturalization Service, acting upon secret information provided by the Canadian Royal Canadian Mounted Police (RCMP) and the Canadian Security Intelligence Service (CSIS). On the basis of this and other information, the Canadian engineer was detained without charges for two weeks, denied access to a lawyer, and deported to ![]() Syria, where he was imprisoned in a three by six-foot cell for more than ten months, beaten, tortured, and forced to sign a false confession. A public campaign waged by his wife, Monia Mazigh, human rights advocates such as Alex Neve, Secretary-General of Amnesty International Canada, and some sympathetic Canadian MPs ultimately led to his release, and the appointment of a public inquiry (June 2004-November 2005). As Audrey Maklin details in her carefully documented account of the case, the inquiry vindicated Arar’s innocence and revealed that the RCMP and CSIS had supplied US officials with “inaccurate and prejudicial” information. Indeed, the RCMP “violated their own protocol by supplying information to the US and Syria without attaching any conditions on how the information would be used” (15)—also true of the information supplied to Austria by British authorities in the spring of 1844 that may have contributed to the execution of the Bandiera brothers in July in Naples. The Arar Inquiry furthermore revealed that, while Canadian consular officials had visited Arar in Syria, they had accepted his “confession” of Al Quaeda connections “with no caveat that the statement may have been extracted through torture”; in addition, they furnished Syrian authorities with questions to ask of another Canadian citizen in Syrian custody, and leaked confidential and sometimes false information to the Canadian media to damage Arar’s reputation (16). Given a comprehensive, factual report that actually addressed the case, unlike the Secret Reports of 1844 in response to Mazzini espionage scandal, the submission of the Arar Inquiry report in September 2006 resulted in a formal apology and financial settlement from the Canadian government and recommendations for policy changes (17-18). Government action was further stimulated by the change of government in Canada between Maher’s rendition and torture in 2002-3, as Stephen Harper’s Conservatives moved from opposition into power—even though subsequent stonewalling on the human rights abuses suffered by Canadian detainees in

Syria, where he was imprisoned in a three by six-foot cell for more than ten months, beaten, tortured, and forced to sign a false confession. A public campaign waged by his wife, Monia Mazigh, human rights advocates such as Alex Neve, Secretary-General of Amnesty International Canada, and some sympathetic Canadian MPs ultimately led to his release, and the appointment of a public inquiry (June 2004-November 2005). As Audrey Maklin details in her carefully documented account of the case, the inquiry vindicated Arar’s innocence and revealed that the RCMP and CSIS had supplied US officials with “inaccurate and prejudicial” information. Indeed, the RCMP “violated their own protocol by supplying information to the US and Syria without attaching any conditions on how the information would be used” (15)—also true of the information supplied to Austria by British authorities in the spring of 1844 that may have contributed to the execution of the Bandiera brothers in July in Naples. The Arar Inquiry furthermore revealed that, while Canadian consular officials had visited Arar in Syria, they had accepted his “confession” of Al Quaeda connections “with no caveat that the statement may have been extracted through torture”; in addition, they furnished Syrian authorities with questions to ask of another Canadian citizen in Syrian custody, and leaked confidential and sometimes false information to the Canadian media to damage Arar’s reputation (16). Given a comprehensive, factual report that actually addressed the case, unlike the Secret Reports of 1844 in response to Mazzini espionage scandal, the submission of the Arar Inquiry report in September 2006 resulted in a formal apology and financial settlement from the Canadian government and recommendations for policy changes (17-18). Government action was further stimulated by the change of government in Canada between Maher’s rendition and torture in 2002-3, as Stephen Harper’s Conservatives moved from opposition into power—even though subsequent stonewalling on the human rights abuses suffered by Canadian detainees in ![]() Afghanistan and the heavy redaction of government files on supposed security grounds made it very clear that there was no new regime of transparency.

Afghanistan and the heavy redaction of government files on supposed security grounds made it very clear that there was no new regime of transparency.

Like the affair of Mazzini’s letters, the Arar affair was an international event, but one that received more media attention in Canada than the US or UK. This attention intensified when an Ottawa journalist who had been “leaked” prejudicial information about Arar by government officials was herself subjected to an RCMP search, together with violation of the principle of protecting confidential sources, producing the irony, as Macklin notes, of “media indignation over the conduct of an investigation into media leaks that smeared Arar’s reputation” (19). The public inquiry ultimately led to a “formal objection” to the US for the rendition of Arar (17), yet still did not produce any substantial check on secret state surveillance of private citizens in either country. In 2007, “US Secretary of State Condoleezza Rice reaffirmed that Maher Arar would not be removed from the US ‘watch list,’ despite his exoneration by the Arar Inquiry” (18). In January 2012, the US Patriot Act was also given sweeping extension by President Obama’s signing of the “National Defence Authorization Act,” giving US authorities the right to arrest and detain “without charge or trial” even American citizens to maintain homeland security (Koring).

Two other recent controversies resonate more directly with the 1844 Post Office espionage case, as electronic media expand both the possibilities of communication and of spying by individuals as well as nation states and corporations. One is the controversial WikiLeaks affair, which has elicited highly conflicting responses, with government officials such as US Secretary of State Hilary Clinton supporting “freedom of information” as they defend diplomatic secrecy (see Schmidt et al). While officials in other Western democracies have largely supported the line taken by Clinton on WikiLeaks, it has also generated some political differences. For example, in October 2011, the Inter-Parliamentary Union of the Council of Europe, representing MPs from 157 countries, unanimously adopted a resolution condemning a ruling by US courts giving the right to American authorities to access the Twitter account of Icelandic MP and former WikiLeaks volunteer Birgitta Jonsdottir (Rushe n. pag.). Like Mazzini with his Young Italy networks, Assange is the animator of a decentralized network of “hactivist” culture (Ludlow), although it has been more difficult for defenders to portray him as a charismatic, if idealistic and uncompromised man of vision, as Carlyle defended Mazzini. Some argue that he is an anti-American, anarchist conspirator (see, e.g., Foreman) precipitating the suffering of innocent people, much as some in the nineteenth century saw Mazzini as a violent conspirator whose plottings resulted in the death of deluded young Italians. Others see him as a whistle-blower and radical, left-wing ideologue, under “house arrest in England for close to two years,” although not “charged with any crime,” and at risk of being extradited to the US, charged with treasonous espionage, and “imprisoned for life or executed” (Goodman).