Abstract

The Socialist League was one of several early socialist groups which arose in Great Britain during the 1880s. Among these, the League was distinctive for its eclectic membership and its focus on education and outreach as the most effective means to social change. Its notable members included William Morris, Tom Maguire, Andreas Scheu, Bruce Glasier, and for a time, Friedrich Engels, Eleanor Marx, and Edward Aveling. During its four years of greatest activity from 1885 through 1889, its vigorous program of lectures, open-air meetings, and publications, including Commonweal, reached a wide audience through campaigns on behalf of free speech, miners’ strikes, an international workers’ movement, and the reorganization of society “from the root up.” Its internationalism, strong support for the Second International, and consistent anti-imperialism gave its revolutionary ideals a broad, forward looking cast. Its focus on education, outreach, and alternative forms of social organization also attracted writers, artists and intellectuals who promoted its holistic ideals through creative works and contributed to its journal Commonweal. On the other hand, as an organization founded before the election of working-class representatives seemed feasible, its continued commitment to advocacy and “pure” socialism—as opposed to party politics—ultimately rendered it less viable than more pragmatically oriented groups such as the emerging Independent Labour Party.

Notable members included William Morris, Tom Maguire, Andreas Scheu, Bruce Glasier, and for a time, Friedrich Engels, Eleanor Marx, and Edward Aveling.[1] Although the League briefly held in uneasy balance anarcho-socialists and Marxist social democrats, it split (as it had begun) over the question of tactics. Eventually, those committed to centralized organization and electoral politics seceded, while the more extreme anarchists, unsuccessful in achieving their alternative goals, responded with militant rhetoric to the provocations of arrest and incarceration.

During its brief floruit, the Socialist League was distinguished by its non-electoral focus as well as its attempts to apply egalitarian principles to its internal affairs. Its democratic organization, in contrast to that of the Social Democratic Federation; its considerable working-class membership, in contrast to that of the mostly middle-class Fabian Society; its internationalism and strong support for the Second International, a partial result of the many continental émigrés in its ranks; and its consistent anti-imperialism, in contrast to the positions of the Social Democratic Federation and Fabians, gave its revolutionary ideals a broad, forward-looking cast. Its focus on education, outreach, and alternative forms of social organization attracted writers, artists and intellectuals who promoted its holistic ideals through creative works and contributed to Commonweal. It also promoted such loosely associated cooperative ventures as the Art Workers Guild, the Arts and Crafts Exhibition Society, and the Liverpool and Edinburgh Art Congresses of 1888 and 1889 (Thompson 557). On the other hand, as an organization founded before the election of working-class representatives seemed feasible, its continued commitment to advocacy and “pure” socialism—as opposed to party politics—ultimately rendered it less viable than more pragmatically-oriented groups such as the Social Democratic Federation, the Socialist Union, the Fabian Society, and the emerging Independent Labour Party.

Despite considerable temperamental and ideological differences both within its ranks and with non-League socialists, during its years of greatest activity the Socialist League managed to coordinate as well as compete with its fellow socialist organizations, joining with kindred groups for major protests, demonstrations, and commemorations, and rallying to present a common front in times of repression. For example, although the police attack on “Bloody Sunday” in November 1887 occurred at a demonstration called by the Social Democratic Federation, Socialist League members had attended the meeting as a body, and the resulting brutality was memorialized by League member William Morris in “A Death Song for Alfred Linnell” and chapter 7 of News from Nowhere.

As the pluralistic emergent labor/socialist movement underwent swift changes during the 1890s, representatives from the Socialist League, Social Democratic Federation and Fabian Society signed a statement of common principles and cooperation on May Day 1893, the same year in which the Independent Labour Party was formed on an initially socialist platform. Although the gains achieved by the Independent Labour Party, and later, the reformist but non-collectivist early Labour Party, would be the closest Britain would come to fulfilling socialist principles in the electoral sphere, the antecedent Socialist League had also helped reorient public opinion toward a more cooperative social organization. Moreover its principles and literary expressions form a continuing critique of the nationalist and capitalist economic interests which, despite the best efforts of reformers, would continue to dominate British political life throughout the next century and beyond.

History:

Council members of the Social Democratic Federation were disturbed by the behavior of Henry Hyndman, who controlled both the internal processes of the Federation and its periodical Justice; he was accused of abrasiveness, pervasive dishonesty, personal arrogance, suppression and distortion of information about branch activity, and as editor of Justice, censorship of all views contrary to his own. Further charges included prejudice against foreign émigrés within the organization, inflated statements to the press, and an obsession with counterproductive public shows of force. In December 1884, the majority of the Council decided that change was necessary and brought in a vote of no confidence by a margin of 9-7. At this point, of course, the nine dissenting members[2] could have controlled the Social Democratic Federation, but they seceded, rightly or wrongly judging that this step would limit internal dissension in the new organization and that the two bodies would be freed to pursue different policies if they so chose.

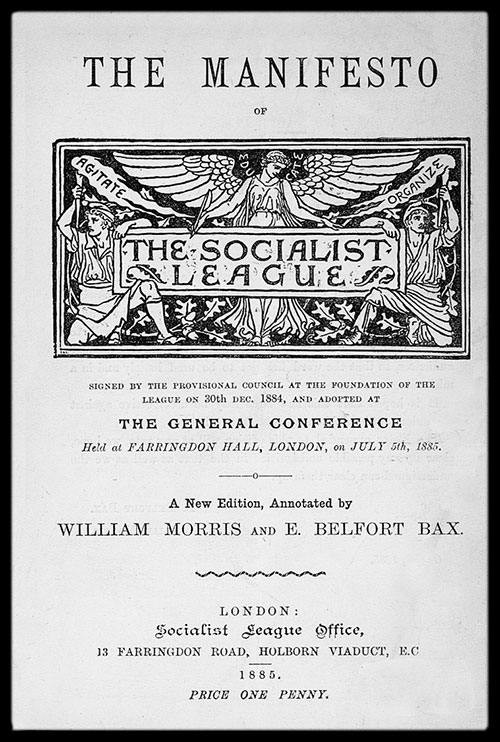

Nearly half of the Social Democratic Federation’s members crossed over into the new organization, and branches were swiftly formed in several districts of London, Leeds, Bradford, Oxford, Glasgow, Edinburgh and elsewhere.[3] E. P. Thompson estimates the early 1887 membership at nearly 1000 paying members (415), and there would likely have been sympathizers who could not or chose not to pay. A new periodical was needed, and William Morris assumed the editorship and support of Commonweal, sold for one penny throughout the branches.

To accomplish their aim of “making Socialists” (Morris’s phrase) the League sponsored an ambitious program of evening lectures, Sunday morning outdoor speeches, contributions to the press, distribution of pamphlets and Commonweal, and participation in numerous protests and demonstrations. Since many workers could not read or afford reading matter, open-air meetings were deemed necessary to convey the League’s message to a wide audience of workers. Such outdoor lectures were quite effective; in London, for example, League representatives at times reportedly attracted as many as 500 auditors to their open-air “pitches.” The Metropolitan Police responded by banning socialist speakers from using public areas and arresting speakers for “obstruction.” As a result, throughout 1885 and 1886 both London and provincial branches of the organization were preoccupied with defending their outdoor speakers from the consequences of these arrests by raising bail, serving as witnesses at court hearings, and publicizing their cause (Thompson 399).

One of the better known of these incidents occurred on 20 September 1885 at ![]() Dod Street in East London, where after a large socialist gathering had dispersed, the police swooped down to arrest eight attendees. These were tried for “obstruction” the next day at the Thames Police Court, and Lewis Lyons, a tailor, was singled out for a sentence of two months hard labor. When members of the audience responded with cries of “Shame,” the police rushed on them and arrested William Morris on a charge of “disorderly conduct” (Thompson 396). Though Morris was released by the magistrate when he learned the identity of his prisoner—an incident which later inspired a scene in Morris’s socialist farce “The Tables Turned”—his arrest helped publicize the denial of public free speech, routinely granted to religious groups but not to socialists, as well as the unequal treatment meted out to alleged offenders of different backgrounds.

Dod Street in East London, where after a large socialist gathering had dispersed, the police swooped down to arrest eight attendees. These were tried for “obstruction” the next day at the Thames Police Court, and Lewis Lyons, a tailor, was singled out for a sentence of two months hard labor. When members of the audience responded with cries of “Shame,” the police rushed on them and arrested William Morris on a charge of “disorderly conduct” (Thompson 396). Though Morris was released by the magistrate when he learned the identity of his prisoner—an incident which later inspired a scene in Morris’s socialist farce “The Tables Turned”—his arrest helped publicize the denial of public free speech, routinely granted to religious groups but not to socialists, as well as the unequal treatment meted out to alleged offenders of different backgrounds.

Arrests continued, however, with the unemployment demonstrations of February 1886 providing the occasion for several more. The socialists likewise persisted, and for a few months in early 1887 the police apparently became more wary. However, this partial truce was ruptured by the aforementioned major police onslaught on 13 November 1887, “Bloody Sunday,” during which mounted police surrounded an unarmed crowd of 6,000 protesters and 30,000 bystanders in and near ![]() Trafalgar Square, beating those entrapped with clubs, arresting 400 persons, and reportedly injuring at least 75.

Trafalgar Square, beating those entrapped with clubs, arresting 400 persons, and reportedly injuring at least 75.

In addition to efforts to spread the “good news” of socialism, throughout 1885-86 League members mounted several attacks against British imperialism, as manifested in Britain’s ongoing conquest of ![]() Egypt and the imposition of martial law in

Egypt and the imposition of martial law in ![]() Ireland. Viewing such government ventures as a means of feeding the maw of “competitive commerce,” in early 1886 League members boldly distributed a pamphlet that condemned Britain for crushing the Egyptian Mahdist independence movement and annexing the

Ireland. Viewing such government ventures as a means of feeding the maw of “competitive commerce,” in early 1886 League members boldly distributed a pamphlet that condemned Britain for crushing the Egyptian Mahdist independence movement and annexing the ![]() Sudan—a courageous act in the face of patriotic fervor after the fall of

Sudan—a courageous act in the face of patriotic fervor after the fall of ![]() Khartoum and the death of General Gordon. Socialist League representatives also introduced resolutions at several public peace meetings condemning the economic motives for the war in Egypt and in April 1886 sponsored a large anti-war meeting of their own. Simultaneously they distributed leaflets, lectured, and attended public meetings on behalf of Irish independence and against the Liberal government’s Coercion Bill for Ireland, passed in 1881 to permit the imprisonment without trial of Irish National League sympathizers. It was, in fact, a meeting called in support of recently arrested Irish nationalists as well as unemployment relief that provided the occasion for “Bloody Sunday.”

Khartoum and the death of General Gordon. Socialist League representatives also introduced resolutions at several public peace meetings condemning the economic motives for the war in Egypt and in April 1886 sponsored a large anti-war meeting of their own. Simultaneously they distributed leaflets, lectured, and attended public meetings on behalf of Irish independence and against the Liberal government’s Coercion Bill for Ireland, passed in 1881 to permit the imprisonment without trial of Irish National League sympathizers. It was, in fact, a meeting called in support of recently arrested Irish nationalists as well as unemployment relief that provided the occasion for “Bloody Sunday.”

By early 1887, because of a series of miners’ strikes in ![]() Northumberland and Lanarkshire,

Northumberland and Lanarkshire, ![]() Scotland provided an opportunity to appeal to disaffected workers on a mass scale. In response, the League distributed thousands of leaflets and organized demonstrations in support of the strikers in Glasgow, Edinburgh, Leeds, Newcastle and elsewhere, with speeches by J. L. Mahon, Tom Macguire, Morris and others. These meetings initially attracted large crowds; a Glasgow meeting in February 1887 reportedly drew 20,000 sympathizers, and a joint meeting of the Socialist League and Socialist Democratic Federation in Edinburgh attracted 12,000. Such outreach efforts helped to establish local branches, buttress trade union support, and influence public sentiment toward socialism as a means of providing solidarity and meaningful long term goals.

Scotland provided an opportunity to appeal to disaffected workers on a mass scale. In response, the League distributed thousands of leaflets and organized demonstrations in support of the strikers in Glasgow, Edinburgh, Leeds, Newcastle and elsewhere, with speeches by J. L. Mahon, Tom Macguire, Morris and others. These meetings initially attracted large crowds; a Glasgow meeting in February 1887 reportedly drew 20,000 sympathizers, and a joint meeting of the Socialist League and Socialist Democratic Federation in Edinburgh attracted 12,000. Such outreach efforts helped to establish local branches, buttress trade union support, and influence public sentiment toward socialism as a means of providing solidarity and meaningful long term goals.

The results for immediate organizing were limited, however, by the Socialist League’s fear that organized trade union workers would hurt their ultimate cause if they acknowledged their employers’ right to set wages, a stance perhaps influenced in Morris’s case by memories of the tame 1870’s house unions that had operated at his original family’s Devonshire Great Consols mining firm. Despite enormous efforts, by late 1887 socialists faced the stern realities of severe government repression and the present inability of alternative forms of social organization such as trade unions or a hoped-for “people’s government” to provide significant redress. Most, including Morris, were thus forced to defer hopes of swift and widespread social transformation.

Despite such stresses, Socialist League members also enjoyed lighter moments. Some attention was diverted to shared activities such as picnics, group singing, and theatrical performances. Morris’s comic farce The Tables Turned: A Socialist Interlude was performed by the ![]() Hammersmith Branch in October 1887, and other convivial occasions were designed to encourage a sense of fellowship. Moreover, members cooperated in contributing to and distributing Commonweal, generally acknowledged as the finest socialist newspaper of its period.

Hammersmith Branch in October 1887, and other convivial occasions were designed to encourage a sense of fellowship. Moreover, members cooperated in contributing to and distributing Commonweal, generally acknowledged as the finest socialist newspaper of its period.

Commonweal 1885-1890:

Edited by Morris from 1885-90 with successive assistant editors Edward Aveling, Ernest Belfort Bax, and H. Halliday Sparling, Commonweal strove to provide its readers with a sense of socialism’s place in an immediate but also ongoing struggle against oppression. It attempted this in several ways: through reports on socialist and other political events in Europe, the Americas, and England; accounts of the activities of current Socialist League branches; pithy socialist commentaries on current events; and theoretical and historical articles on such topics as imperialism, “scientific socialism,” the nature of a socialist agenda, contrasts between England in the 1840s and 1880s, and a “people’s history” from the earliest times to the present.[4] Perhaps most important, however, it attempted to present socialist views attractively and persuasively through literary works, and to this end it encouraged original poetry and translations—Elizabeth Miller reports that 309 poems were printed during its brief existence (195)—as well as fiction, dramatic sketches, and dialogues. She notes that the periodical sought to create “not so much a subculture as an alternative culture based in the print space of the paper” (51).

More than a hundred years later, much of Commonweal can still be read with pleasure (http://morrisedition.lib.uiowa.edu/PeriodicalsPublications/Commonweal1885-89). The “Notes on News” and short articles, such as “Misanthropy to the Rescue!,” “The Husks that the Swine Do Eat,” and “Facing the Worst of It,” have attracted little notice, but these short “opinion pieces,” like current Twitter and blog posts at their best, exhibit humor, sarcasm, and pithy concision. “Notes on News” were Morris’s running commentaries on the events of the day, often expressing outrage or disgust in response to incidents reported in the London Daily News, edited until 1886 by the anti-imperialist left-Liberal Frank Harrison Hill. Even for the reader unacquainted with their original points of reference, the “Notes” invoke a lively sense of issues still unresolved in our century: media bias, unequal justice, official hypocrisy, environmental degradation, and widespread scarcity in the face of excess.

Though Commonweal published the literary works of several writers,[5] those by Morris have been most remembered. Although his pre-socialist writings had featured motifs of struggle, postponed desire, and the search for romantic and political ideals, the need to present both the aspirations and difficulties of an embattled socialism to a popular audience helped add specificity and a wider resonance to his plots. Arguably, too, the newspaper’s serial format encouraged short, dramatic scenes rather than leisurely and allusive narration. Prior to writing for Commonweal, Morris had been chiefly a poet, author of epics such as The Earthly Paradise and Sigurd the Volsung. The April 1885 issue of Commonweal accordingly featured the first installment of an eleven-part socialist poem, “The Pilgrims of Hope,” set during the ![]() Paris Commune, an uprising that his audience would have seen as anticipating a similar potential struggle of their own. Though not published in book form until after Morris’s death, “Pilgrims” is unique among poetic epics of the period in its dual communist and feminist allegiances.

Paris Commune, an uprising that his audience would have seen as anticipating a similar potential struggle of their own. Though not published in book form until after Morris’s death, “Pilgrims” is unique among poetic epics of the period in its dual communist and feminist allegiances.

At this point, Morris shifted to serialized prose cast in largely dialogic form; A Dream of John Ball appeared in Commonweal from November 1886 through June 1887, and News from Nowhere from January through October 1890. He also turned to more distant temporal settings, both to educate his audience and to encourage hope in the face of immediate setbacks.[6] A Dream of John Ball evokes earlier English prototypes of revolt in a moving fictionalized account of the last days of the revolutionary priest John Ball, who had helped raise an army to confront King Richard II and his nobles during the People’s Revolt of 1381. The tale’s protagonist, a narrator/time-traveler who serves as Morris’s spokesperson, returns to the fourteenth century to interview the revolutionary priest shortly before the latter’s death, and the two men strive together to understand how revolutionary goals can be proximately defeated and yet survive into the future. Finally, News from Nowhere, one of several dozen late nineteenth-century British utopias, is arguably the most searching of these in its vision of a future egalitarian society in accord with human needs, and its exploration of the forces ranged against its attainment: competitiveness, violence, and disdain for work, nature, and art.

Morris also composed other creative works for the Socialist League and/or Commonweal: songs for use in demonstrations and meetings, published as Chants for Socialists; short parables, such as “An Old Story Retold,” later published as “A King’s Lesson”[7]; dialogues such as “The Boy-Farms at Fault” and “The Reward of Labour. A Dialogue”; and the previously mentioned The Tables Turned, a send-up of establishment figures such as the Archbishop of Canterbury, the now-reactionary Lord Tennyson, and Magistrate Saunders, the judge at Morris’s trial for “disorderly conduct.” Bax and Morris’s serialized “Socialism from the Root Up” (1886) presented readers with a socialist alternative to conventional political history and supplemented Morris’s projections of idealized fellowship in his creative work. In “From the Root Up,” later revised and expanded as Socialism: Its Growth and Outcome (1893), the authors offered explicit suggestions for how a socialist society could be organized in such areas as religion, entertainment, architecture, urban planning, and land management, providing a partial antidote to critics who have found News from Nowhere lacking in details regarding the practical arrangements suitable for a utopian society.

The Socialist Diary and Other Writings:

Another effort which lay unpublished until 1981 was Morris’s Socialist Diary, maintained from 25 January through 25 April 1887 as a snapshot of his activities and private reactions during a frenetically busy period at the midpoint of his socialist endeavors. The Diary records Morris’s understated but honest assessment of the factors that would frustrate the formation of a mass socialist movement and eventually exclude him from active political leadership outside of the local Hammersmith Socialist Society. Though some of the initial entries have the tone of material intended for publication, most likely in Commonweal, the effort was suspended in April 1887 under the press of other obligations. Nonetheless, the Diary leaves a vivid record of Morris’s activities during this three-month period, among them participation in large rallies or demonstrations; attendance at internal council meetings; occasional speaking engagements to non-socialist groups; stints of outdoor preaching at ![]() Hyde Park, Beadon Road in Hammersmith, and elsewhere; and his interactions with the many League branches at which he spoke, among them Glasgow, Edinburgh, Dundee, Newcastle, and others in the greater London area.

Hyde Park, Beadon Road in Hammersmith, and elsewhere; and his interactions with the many League branches at which he spoke, among them Glasgow, Edinburgh, Dundee, Newcastle, and others in the greater London area.

Although Commonweal formed only one component of an eclectic cultural mix, the number of sometime Socialist League members or attendees who wrote for Commonweal and/or authored pamphlets or books nonetheless merits special notice. A partial list of pamphlets or books published by members would include (arranged alphabetically):

Edward Aveling and Eleanor Marx: The Woman Question

Ernest Belfort Bax: The Religion of Socialism; The Ethics of Socialism

Thomas Bolas: Confiscation of All Railroad Property

Edward Carpenter: Toward Democracy. A Prose Poem

John Carruthers: The Political Economy of Socialism, Socialism and Radicalism

Friedrich Engels: The Condition of the Working Class (whose introduction to the 1885 English translation had appeared in Commonweal); The Origin of the Family, Private Property and the State

A.K. Donald, ed.: Melusine

John Glasse: Modern Christian Socialism: From 1848

Bruce Glasier: Working Men Indeed!, Socialism in Song

Fred Henderson: Echoes of the Coming Day: Socialist Songs and Rhymes; By the Sea and Other Poems; The Case for Socialism

J. L. Joynes: Socialist Rhymes

Joseph Lane: An Anti-Statist Manifesto

Tom Maguire: Machine-Room Chants

John L. Mahon: A Labour Programme

Andreas Scheu: songs in Chants of Labour, Umsturzkeime [Reminiscences]

H. Halliday Sparling, ed.: Irish Minstrelsy; Men Versus Machinery; Needs and Ideals.

In aggregate, no reformist group of the period except the Fabians could claim greater literary contributions to the wider culture.

Dissolution of the League:

The anarchist and Marxist wings of the League differed both on the nature of an ideal socialist society and the means necessary for bringing it about. Whereas the anarcho-socialists, many raised in syndicalist European traditions, advocated the forming of an alternate government “from the root up” through workers’ organizations, a hoped-for general strike, and an alternative Labor Parliament, the Marxist members of the League, akin to European-style state-socialists, favored a more central organization and wished to run candidates for the currently existing parliament. Although at the third annual conference in May 1887 the anti-parliamentarians narrowly prevailed, the two groups soon separated, with Eleanor Marx, Friedrich Engels, and others succeeding in August 1888 to form the ![]() Bloomsbury Socialist Society, and in time, to reunite with the Social Democratic Federation.

Bloomsbury Socialist Society, and in time, to reunite with the Social Democratic Federation.

After 1888, the anarchist faction of the weakened organization was unable to attract sufficient new members, and as they assumed fuller control during 1889 and 1890, they removed or alienated moderate members such as William Morris and his colleagues, who not only opposed appeals to “actionism” and violence on moral grounds but warned of their potential irreparable harm to the movement. Morris’s own position on revolutionary violence had evolved since the mid-1880s, as he would later argue forcefully in “Communism, i. e. Property” (c. 1893):

The change effected by peaceable means would be done more completely and with less chance, indeed with no chance of counter-revolution. . . . In short I do not believe in the possible success of revolt until the Socialist party has grown so powerful in numbers that it can gain its end by peaceful means, and that therefore what is called violence will never be needed. . . . And here I will say once for all, what I have often wanted to say of late, to wit, that the idea of taking any human life for any reason whatsoever is horrible and abhorrent to me. (“Communism, i. e. Property” 20)

Morris’s last major publication in Commonweal was, fittingly, his utopian romance News from Nowhere, serialized from January through October 1890 and thus continuing for six months after his removal as editor in April. This imaginative tribute to a society of peaceful fellowship ends with a famous adjuration by Ellen, the representative of the new society:

[“]Go back again, now you have seen us, and your outward eyes have learned that in spite of all the infallible maxims of your day there is yet a time of rest in store for the world, when mastery has changed into fellowship—. . . Go on living while you may, striving, with whatsoever pain and labour needs must be, to build up little by little the new day of fellowship, and rest, and happiness.”

To which Morris’s narrator answers,

“Yes, surely! and if others can see it as I have seen it, then it may be called a vision rather than a dream.” (Collected Works 16.210-11)

If those others could not see it, unfortunately, the vision would inevitably be postponed.

Afterward:

Historians have often regretted the divisions within British socialism during the 1880s and have found the Socialist League’s anti-parliamentary stance inexplicably quietist. Though valid from some perspectives, such judgments may assume that a movement that in aggregate had attracted only a few thousand members could, through altering its priorities, have succeeded in gaining direct political influence in late nineteenth-century Britain. Yet London Socialist Democratic Federation candidates in 1885 polled fewer than 50 votes, and not until 1891 was a professed socialist elected to office, in this case to the London County Council. Moreover, despite rivalries, the different wings of the socialist movement also supplemented one another in employing electioneering and advocacy along parallel tracks, so that to some degree division enabled several groups to carry out useful complementary roles in the service of common goals.

Moreover, as anyone who has tried political organizing can testify, one can only accomplish so much with limited time and resources. Had the League devoted its finite energies to conducting several, most likely failed, political campaigns, its members might have been less successful at accomplishing their stated mission: to advocate for radical change in the “infallible maxims” and belief systems that underlie and motivate political affairs. In its four or five years of greatest activity, the Socialist League sponsored thousands of lectures, open-air meetings, public rallies, and other educational efforts; distributed many thousand pamphlets, leaflets, newspapers and books; reached out systematically to reformist and radical non-Socialist groups to convey a socialist alternative; and facilitated a socialist literature whose audience reached well into the next century.

Each of these efforts was in itself small, but in aggregate they helped shift public opinion in Britain, influencing many intellectuals and workers of the fin de siècle and beyond, heralding the rise of the Independent Labour and Labour Parties, and contributing a radical critique of normative social stratification and repression to a period of intellectual ferment. Moreover, the conundrum which Morris and his Socialist League comrades identified but could not solve—the tendency of initially reformist political parties to assume more conservative positions when once in power—continues to frustrate would-be alternative political and social movements that seek to alter entrenched power relations and (as the Socialist League framers would have put it) usher in “the social revolution.”

published April 2015

HOW TO CITE THIS BRANCH ENTRY (MLA format)

Boos, Florence. “The Socialist League, founded 30 December 1884.” BRANCH: Britain, Representation and Nineteenth-Century History. Ed. Dino Franco Felluga. Extension of Romanticism and Victorianism on the Net. Web. [Here, add your last date of access to BRANCH].

WORKS CITED

No book-length study of the Socialist League has yet been written; such a history might give proper attention to its work in the provinces and the relation between provincial Socialist League branches and parliamentary campaigns. Another yet-unexplored topic is the influence on Commonweal of the strongly anti-imperialist views of left-Liberal Daily News editor Frank Harrison Hill, who was forced to leave his post in 1886.

The Socialist League Archives are preserved at the International Institute of Social History in Amsterdam. An account of aspects of Socialist League activities relevant to William Morris appears in Edward Thompson’s biography, William Morris; Thompson favors the electoral wing of the League and gives less coverage to the League’s anarchist associates. The best account of Commonweal and its literary context in the radical press is Elizabeth Miller’s Slow Print: Literary Radicalism and Late Victorian Print Culture (both cited below).

The Archives of the Socialist League (UK). Collection ARCH01315. International Institute of Social History, An Institute of the Royal Netherlands Academy of Arts and Sciences. Web. 19 Jan. 2015.

Boos, Florence, ed. “From the Archive: William Morris’s ‘Communism—i. e. Property: A Partly Unpublished Essay,” Newsletter of the William Morris Society in the United States (Summer 2009): 16-21. Web. 19 Jan. 2015.

Boos, Florence and Patrick O’Sullivan. “Morris’s Socialism and the Devonshire Great Consols.” Journal of William Morris Studies 20.1 (Spring 2012): 11-39. Print.

Clayton, Joseph. The Rise and Decline of Socialism in Great Britain, 1884-1924. London: Faber and Gwyer, 1926. Print.

Cole, George M. A History of Socialist Thought. 7 vols. London: Palgrave Macmillan, 2003. Print

Hulse, John. Revolutionists in London: A Study of Five Unorthodox Socialists. Oxford: Clarendon P, 1970. Print.

McCarthy, Fiona. William Morris: A Life for Our Time. London: Faber and Faber, 1994. Print.

Miller, Elizabeth. Slow Print: Literary Radicalism and Late Victorian Print Culture. Stanford: Stanford UP, 2013. Print.

Morris, William. The Collected Letters of William Morris. Ed. Norman Kelvin. 4 vol. Princeton: Princeton UP, 1984-1996. Print.

—. The Collected Works of William Morris. Ed. May Morris. 24 vols. London: Longmans, 1910-1915. Print. (vol. 16 is News from Nowhere; vol. 22 is “Hopes and Fears for Art” and “Lectures on Art and Industry”; vol. 23 is “Signs of Change” and “Lectures on Socialism”)

—. The Tables Turned. Ed. Pamela Bracken Wiens. Athens: Ohio State UP, 1994. Print.

—. “William Morris’s ‘Socialist Diary.’” Marxist Internet Archive. 2005. Web. 19 Jan. 2015. Rpt. of “William Morris’s ‘Socialist Diary.’” Ed. Florence S. Boos. London: The Journeyman P, 1985.

Pierson, Stanley. Marxism and the Origins of British Socialism: The Struggle for a New Consciousness. Ithaca: Cornell UP, 1973. Print.

Sargent, Lyman. “William Morris and the Anarchist Tradition.” Socialism and the Literary Artistry of William Morris. Eds. Florence S. Boos and Carole G. Silver. Columbia: U Missouri P, 1990. Print.

Thompson, E. P. William Morris: Romantic to Revolutionary. 2nd. ed. New York: Pantheon, 1977. Print.

Vaninskaya, Anna. William Morris and the Idea of Community: Romance, History and Propaganda, 1880-1914. Edinburgh: Edinburgh UP, 2010. Print.

ENDNOTES

[1] Other prominent or notable members included Philip Webb, Walter Crane, Emery Walker, Raymond Unwin, Richard Cobden-Sanderson, Sydney Cockerell, James Mavor, Edward Carpenter, and Ernest Belfort Bax.

[2] These were William Morris, Eleanor Marx, Edward Aveling, Ernest Belfort Bax, Joseph Lane, Robert Banner, Sam Mainwaring, W. J. Clark, and John Lincoln Mahon.

[3] The latter two were affiliated with the Scottish Land and Labour League. By June 1886 additional branches had been formed in Manchester, Oldham, Leicester, Dublin, Birmingham, and Norwich, and by December in several more London districts and in Hull, Lancaster, Walsall, North Shields (east of Newcastle), and Hamilton, Lanarkshire.

[4] The articles mentioned were written, respectively, by Bax, Aveling, Scheu, Engels, and Bax and Morris in a series, “Socialism from the Root Up.”

[5] Among the poems were those by Bruce Glasier, Tom Maguire, J. L. Joynes, Reginald Beckett, and C. W. Beckett, as well as translations by J. L. Joynes and Laura Lafargue (Miller 194-204).

[6] Morris’s prior romances written during this period, The House of the Wolfings (1888) and The Roots of the Mountains (1889)—perhaps begun with Commonweal in mind, but in the event not included—dramatize pre- and early-medieval European history as Morris then viewed it, reversing the values of Gibbon’s pro-Roman Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire to celebrate the struggle of so-called “barbarians” to throw off corrupt Roman domination.

[7] Also in Justice, 19 January 1884, “An Old Fable Retold.”