Abstract

By convention the launch of the so-called “golden age” of wood-engraved illustration in Britain, also known as “the sixties,” is Edward Moxon’s publication, in May 1857, of Alfred Tennyson’s Poems, with 54 wood-engraved illustrations designed by 8 artists, including the Pre-Raphaelites John Everett Millais, William Holman Hunt, and Dante Gabriel Rossetti. Although the Moxon Tennyson was neither a commercial nor critical success on first publication, before the decade was out its Pre-Raphaelite designs were considered a touchstone for artistic illustration, a reputation that continues today. Without disputing the significance of this aesthetic achievement, I want to shift critical focus to the Moxon Tennyson’s status as mass-produced work of art in the age of mechanical reproduction. My interest here is in how its visual communication was expressed through its reproductive technology at the historical moment of its production and reception. This essay re-positions the Moxon Tennyson as a textual event by reading it in the context of documentary, satiric, and artistic wood-engraved images selected from the crucial six-month period after its publication. By situating the Pre-Raphaelite illustrations for Tennyson’s Poems in relation to representations in the public press of such disparate events as the Art Treasures of the United Kingdom Exhibition in Manchester, the reportage on Indian uprisings at Meerut and Cawnpore, the Matrimonial Causes Act, and the Christy Minstrels show in London, I aim to show the complex ways in which the Moxon Tennyson was a worldly event, caught up in, and contributing to, ways of seeing and knowing in 1857.

Figure 1: Cover, Alfred Tennyson, Poems. Illustrated. (1857). London: Moxon, 1859. Private collection, used with permission.

All books are, of course, textual events, but the publication of the illustrated volume that has come to be known as the Moxon Tennyson (Fig. 1) has proven to be a particularly generative one. 1857—the year in which Edward Moxon published Alfred Tennyson’s Poems with 54 wood-engraved illustrations designed by 8 artists, including the Pre-Raphaelites John Everett Millais, William Holman Hunt, and Dante Gabriel Rossetti—has traditionally been associated with the launch of the period known as “the ‘sixties,” the so-called “golden age” of wood-engraved illustration (Goldman; Reid; White). According to Gleeson White, “The whole modern school of decorative illustrators regard it rightly enough as the genesis of the modern movement” (105). White’s English Illustration: “The Sixties” 1855-70, directed at fin-de-siècle collectors intent on acquiring accessible Pre-Raphaelite art in the form of wood-engraved prints in books and magazines of the 1860s, established a long tradition of viewing the Pre-Raphaelite illustrations to Tennyson’s poems as stand-alone works of art. However, while this approach pays homage to the artistic achievement of the period’s gift books and illustrated periodicals, it also has the effect of dematerializing and decontextualizing the objects of study. The illustrations not only appear extractable from, and separate to, the book they were made for and bound up with, but also—insofar as they are considered in relation to the fine art of painting, rather than the mass art of wood engraving—detached from their mode of production and their conventions of visual communication with readers.

In examining 1857 as a historical node, with wood engraving as its expressive medium, I propose to re-position the Pre-Raphaelite illustrations of the Moxon Tennyson within their contemporary visual moment. Viewed through the lens of mechanical reproduction, nineteenth-century visual culture displays two important characteristics: 1) the widespread circulation of images of all kinds in Victorian everyday life, shaping new ways of seeing and knowing; and 2) the blurring of boundaries between the categories of fine and popular art. The wood-engraved images of 1857—whether artistic, as in the Pre-Raphaelite designs for Tennyson’s Poems; documentary, as in the visual journalism of The Illustrated London News; or satiric, as in the political cartoons of Punch—were not authenticated by what Walter Benjamin calls the “aura” of a work of art. Detached from any sanctified location in space or time, Victorian wood-engraved images were given authority by the commercial processes and industrial conditions of mass publishing. The significance of wood-engraved illustrations thus lies in their plurality rather than their uniqueness, and in their ability to bring distant images into the user’s immediate presence (Benjamin 65). Moreover, as Brian Maidment reminds us, wood-engraved images, like other representations pervading every aspect of Victorian daily life, are “ideological formations which, whether consciously or unconsciously, are shaped by the cultural values and social aspirations of both make[rs] and audience” (Reading Popular Prints 11). This essay traces some of the ideological formations of racialized, gendered, and classed identity inscribed in works of wood-engraved art from a single six-month period of mechanical reproduction, May–October 1857. By situating the Pre-Raphaelite illustrations for Tennyson’s Poems in relation to representations in the public press of such disparate events as the Art Treasures of the United Kingdom Exhibition in Manchester, the opening of the British Library, the first Pre-Raphaelite Exhibition in Russell Square, the reportage on Indian uprisings at Meerut and Cawnpore, the Matrimonial Causes Act, and the Christy Minstrels’ show in London, I aim to show the complex ways in which the Moxon Tennyson was a worldly event, caught up in, and contributing to, ways of seeing and knowing in 1857.

Wood Engraving: Art, Technology, and Codes of Representation

The capacity of wood engraving as a technology of mass production was realized in the late eighteenth century in Thomas Bewick’s artisanal studio in ![]() Newcastle. The traditional woodcut method of cutting lines into the side of a plank with a knife had served as the technology for image reproduction in popular street culture’s broadsides and chapbooks for centuries. Bewick’s innovation was to use a graver to dig out the “whites” of a design on the end-grain of a piece of hard wood such as boxwood, notable for its close grain and light color. This methodology resulted in a finely detailed wood engraving, a form of relief reproduction ideally suited to being set up with letterpress type.

Newcastle. The traditional woodcut method of cutting lines into the side of a plank with a knife had served as the technology for image reproduction in popular street culture’s broadsides and chapbooks for centuries. Bewick’s innovation was to use a graver to dig out the “whites” of a design on the end-grain of a piece of hard wood such as boxwood, notable for its close grain and light color. This methodology resulted in a finely detailed wood engraving, a form of relief reproduction ideally suited to being set up with letterpress type.

Bewick’s artisanal method was quickly adapted to the conditions of industrial capitalism, with large engraving firms taking on the reproduction of images for the nineteenth century’s massive commercial outpouring of illustrated books and periodicals. The art of wood engraving in the age of mechanical reproduction was dependent on the division of labor and mediated by manual technologies. After the artist drew his design in reverse on the woodblock, the engraver would cut out the whites, establish shading by a series of cross-hatching and parallel lines, and allow the outlines to stand out in relief, ready for inking and printing. Since the ends of boxwood were small—generally not much bigger than 3” x 5,” and often even smaller—a large image would require a number of woodblocks. These would be bolted together to receive the artist’s design, then taken apart and distributed to various engravers to facilitate speed and efficiency, and finally reunited at press time. Although boxwood was a hard enough grain to withstand the printing process, the woodblocks were usually stereotyped or electrotyped. This process, which involved casting a mould of the block in metal, preserved the original woodblock, while the facsimile could produce multiple copies on high-speed steam presses.

While other forms of mechanical reproduction were in use in the nineteenth century, “[t]he era of mass produced woodblock illustration very nearly coincided,” as Sally Mitchell observes, “with Queen Victoria’s reign” (870). Combined with improved technologies for mechanized paper making and steam-powered, multiple-cylinder stereotype printing, the possibilities inherent in wood-engraved reproduction were realized in large print runs of illustrated material at relatively low cost from the 1830s to the 1890s, when photomechanical processes replaced wood engraving as the dominant mode of image reproduction. In 1832, two important pictorial magazines of information and entertainment—the Penny Magazine, the organ of The Society for the Diffusion of Useful Knowledge, and the Saturday Magazine, the organ of The Society for Promoting Christian Knowledge—were launched. Profusely illustrated with wood engravings, these were among the first pictorial magazines to attract and maintain a large periodical readership, and may be seen as marking the beginning of a modern mass culture (Anderson 3).

The illustrated format ensured the commercial success of the first popular weeklies to combine image and text: Punch (launched 17 July 1841) and The Illustrated London News (launched 14 May 1842). Although both were mass-circulation periodicals, shaping and reflecting the views of readers through a predominantly visual strategy, their images drew on distinct representational conventions. Punch carried on the longstanding tradition of British satiric illustration, with the “Large Cut” or full-page wood-engraved political cartoon on a topical event forming the definitive key to each week’s issue. In The Illustrated London News (ILN), on the other hand, the wood-engraved lines claimed documentary realism rather than caricature as their representational mode.[1] The weekly illustrations of Victorian social life and topical events in these magazines and other periodicals constructed modern ways of seeing and knowing for a reading nation. By 1857, when Moxon published Tennyson’s illustrated Poems, these large-circulation magazines had established a range of visual codes and conventions, familiar to a broad middle-class readership, which brought news and public events up close and personal in the daily lives of ordinary Victorians.

In designing illustrations for Moxon’s edition of Tennyson’s Poems, the Pre-Raphaelite artists realized the poetic potential of the wood-engraved image as a medium for pictorial response to literature.[2] Established in September 1848 by Dante Gabriel Rossetti, William Holman Hunt, and John Everett Millais, the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood was committed to a visual/verbal and collaborative aesthetic. (On Dante Gabriel Rossetti, see Elizabeth Helsinger, “Lyric Poetry and the Event of Poems, 1870.″) By 1857, the Brotherhood had long been disbanded, but Pre-Raphaelitism as an artistic movement continued to have significant impact on the development of decorative arts in Victorian Britain. (On the impact of the Pre-Raphaelites on the decorative arts, see Morna O’Neill, “On Walter Crane and the Aims of Decorative Art.”) Indeed, during the Long Vacation of 1857, Pre-Raphaelitism’s second phase got underway with the painting of the ![]() Oxford Union Debating Hall murals on Arthurian themes.[3] As literary artists whose paintings were inspired by poetic subjects, the Pre-Raphaelites might seem inevitably interested in the book arts and illustration. Yet it does not necessarily follow that easel painters, used to working in color in a tonal medium, will also be strong in linear black-and-white, or that fine artists accustomed to executive control over every detail of their work could adapt to the more-or-less industrial conditions of art in the age of mechanical reproduction.

Oxford Union Debating Hall murals on Arthurian themes.[3] As literary artists whose paintings were inspired by poetic subjects, the Pre-Raphaelites might seem inevitably interested in the book arts and illustration. Yet it does not necessarily follow that easel painters, used to working in color in a tonal medium, will also be strong in linear black-and-white, or that fine artists accustomed to executive control over every detail of their work could adapt to the more-or-less industrial conditions of art in the age of mechanical reproduction.

When Millais, Hunt, and Rossetti accepted the commission from Moxon to illustrate Tennyson’s poetry, they were able to choose their own poem (as long as another artist had not selected the same scene), subject, and style. But here artistic authority over their work was at an end. Having drawn their design on the woodblock provided (the size of which was pre-determined by the printers) they surrendered their work to an engraver selected for them by the Brothers Dalziel. Hired by Moxon to oversee the artistic contents and printing of the illustrated Poems, the Dalziels engraved about 25% of the 54 woodblocks themselves, subcontracting the rest to 5 engravers outside their own firm.

From the artist’s point of view, the technology of wood engraving meant the engraver destroyed their original drawing in the process of translating a unique design into a format that could produce multiple copies. In the hands of the engraver, the artist’s drawing on the woodblock was cut out and its nuanced tonal effects interpreted “by the stern realities of black and white” (Dalziels 86n). The resulting relief was set up with the type and printed in ink and paper of the printer’s choosing; the Dalziels, not the artists, approved the impressions. Although illustrators (like authors) had the ability to make some corrections at the proof stage, they ultimately had to operate within the commercial conditions of collaborative authorship and industrial piece-work. In the age of mechanical reproduction and the wood-engraved print, “the presence of the original” could no longer be “the prerequisite to the concept of authenticity” (Benjamin 65). Instead, the bibliographic forms of verification that publishing practices confer on an author’s work became the authenticating structure for an artist’s design. Illustration in the ‘sixties was a mass art designed to be multiple rather than unique.

Despite these constraints, Pre-Raphaelite artists insisted on treating illustration on a par with easel painting—thereby blurring the traditional distinctions between fine art and decorative art. They drew “from nature” for their illustrations, using live models, specific landscapes and architectures, and carefully selected domestic objects. Their compositions were the result of detailed studies of bodies, hands, draperies, positions. Rather than resisting the flat plane of the two-dimensional page, they embraced it as a design challenge, eliding the middle ground, focusing on a large central figure, and treating all pictorial details decoratively and symbolically. The final product was often a mini-masterpiece of critical, intellectual, and creative endeavor.

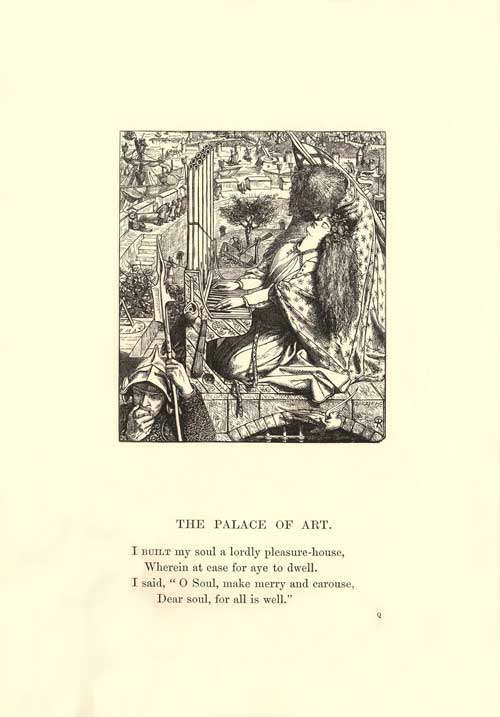

Figure 2: Dante Gabriel Rossetti, “St. Cecily,” for “Palace of Art.” Alfred Tennyson, Poems. Illustrated. (1857) London: Moxon, 1859. 113. Private Collection, used with permission.

The Pre-Raphaelite illustrations for the Moxon Tennyson appalled and delighted Victorian readers for all of these reasons. Collectively, they established an entirely new approach to the art of literary illustration, one that influenced book artists for the remainder of the century and well into the twentieth. John Ruskin, who had been the first art critic to champion the Pre-Raphaelites when they began showing their paintings, was also quick to praise their illustrations when they appeared in print. In an appendix to his Elements of Drawing, published a month after the Moxon Tennyson, Ruskin treated the Pre-Raphaelite designs as genuine works of art, “with which no other modern work can bear the least comparison” (224). Although he quibbled about wood engraving as an adequate reproductive process for fine art, Ruskin essentially acknowledged that the Moxon Tennyson had introduced the wood-engraved image as an art form in the age of mechanical reproduction by naming Rossetti’s “St. Cecily” (Fig. 2) the acme of artistic book illustration.

May 1857

The Moxon Tennyson was published in May 1857, perhaps the most eventful month of an eventful year.[4] In London, the ![]() British Library Reading Room opened; for a week, a curious public streamed in for a special open viewing of its domed ceiling, elevated stacks of gilt-spined books, and blue leather reading tables radiating out from its central core of power and knowledge, the librarian’s desk.[5] After this spectacle, the doors closed to all except those holding Readers Tickets, who could access, open, and read books deposited in the National Library—including, of course, Tennyson’s illustrated Poems. Around the corner in

British Library Reading Room opened; for a week, a curious public streamed in for a special open viewing of its domed ceiling, elevated stacks of gilt-spined books, and blue leather reading tables radiating out from its central core of power and knowledge, the librarian’s desk.[5] After this spectacle, the doors closed to all except those holding Readers Tickets, who could access, open, and read books deposited in the National Library—including, of course, Tennyson’s illustrated Poems. Around the corner in ![]() Russell Square, the Pre-Raphaelites held the first exhibition devoted solely to their work from 25 May-25 June. Included among the 72 works listed in the catalogue were “Designs on Wood for Tennyson’s Poems.” Rather than either pencil studies for the drawings, or the carved woodblocks themselves, this exhibit consisted of photographs of the illustrations drawn on the woodblock before the engravers had cut out their original lines (D.G. Rossetti II.181n1). May 1857 thus marks some curious moments in Victorian visual culture: books and reading were on view as mass spectacle, while the reproductive art of photography preserved the aura of unique originals, then existing only in multiple prints, in an exhibition of fine art.

Russell Square, the Pre-Raphaelites held the first exhibition devoted solely to their work from 25 May-25 June. Included among the 72 works listed in the catalogue were “Designs on Wood for Tennyson’s Poems.” Rather than either pencil studies for the drawings, or the carved woodblocks themselves, this exhibit consisted of photographs of the illustrations drawn on the woodblock before the engravers had cut out their original lines (D.G. Rossetti II.181n1). May 1857 thus marks some curious moments in Victorian visual culture: books and reading were on view as mass spectacle, while the reproductive art of photography preserved the aura of unique originals, then existing only in multiple prints, in an exhibition of fine art.

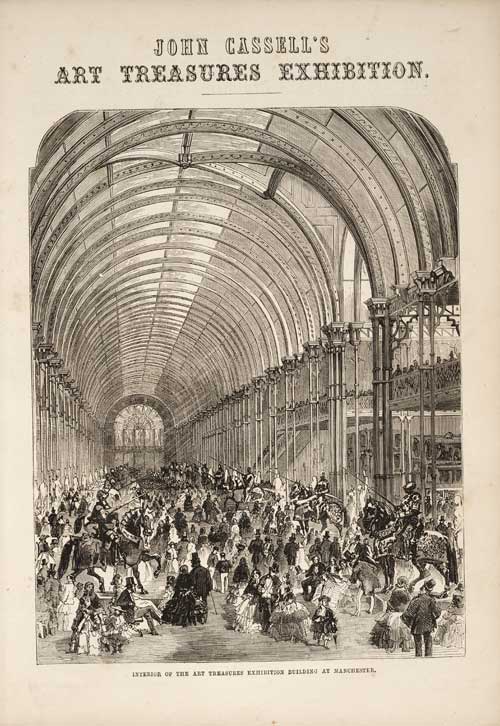

Figure 3: Illustration for John Cassell’s Art Treasures Exhibition: Engravings of the Principal Masterpieces (W. Kent, 1858), 1. Courtesy of Toronto Reference Library

Far from these national scenes of making, viewing, and reading, a momentous event occurred on the edges of empire. On 10 May 1857 in ![]() Meerut, the so-called Indian Mutiny (or first Indian War of Independence) was launched when

Meerut, the so-called Indian Mutiny (or first Indian War of Independence) was launched when ![]() Bengali troops (Sepoys) revolted against their British officers. The rebellion quickly spread to other parts of

Bengali troops (Sepoys) revolted against their British officers. The rebellion quickly spread to other parts of ![]() India and continued throughout the next year. In the age of mechanical reproduction, the Indian Mutiny was very much a textual event for British readers, a historical narrative made and remade in a wide array of visual and verbal representations.[7] During a year of violence between 1857 and 1858, The Illustrated London News carried these distant events into Victorian homes on a weekly basis. Readers could view wood-engraved maps of the subcontinent; portraits of British officers and Indian rebels; images of soldiers, women, and children; views representing local architecture, costume, and landscapes; and scenes of horrific massacre, execution, and slaughter.

India and continued throughout the next year. In the age of mechanical reproduction, the Indian Mutiny was very much a textual event for British readers, a historical narrative made and remade in a wide array of visual and verbal representations.[7] During a year of violence between 1857 and 1858, The Illustrated London News carried these distant events into Victorian homes on a weekly basis. Readers could view wood-engraved maps of the subcontinent; portraits of British officers and Indian rebels; images of soldiers, women, and children; views representing local architecture, costume, and landscapes; and scenes of horrific massacre, execution, and slaughter.

Peter Sinnema reminds us that, in order to sell, The Illustrated London News had to be perceived by the public as a guarantor of authenticity in visual and verbal representation: “[a]s a commodity, the news took as a precondition its anchorage in truth” (10). The images published in the ILN therefore claimed realism as their graphic convention, despite the necessary mediation of wood engravers and other makers. In fact, the process of bringing these documentary images of the rebellion to the public was long and complicated. At first, the ILN had to rely on photographs on hand in London representing Indian cities, forts, and settlements referenced in the reports received by telegraph and mail. As the military engagement continued, the newspaper began to receive drawings and maps from British civil servants, sea captains, travelers, and officers on location in India, who mailed in their sketches to the editor (Figs. 4 and 5). In the absence of an artist on site, the ILN had to rely on this ad hoc visual journalism by correspondents, with no means of verification other than that provided in accompanying letters.[8] Translated by engravers into prints for the periodical, each of these images appeared to articulate actual conditions in India through the accepted graphic convention for documentary realism: the black-and-white wood engraving.

Figure 4, Left: “Engraving of Nana Sahib from a Sketch recently received from India by Major O Gandini,” ILN, 1857; Figure 5, Right: _The Illustrated London News_ 1.1 (14 May 1842). Both courtesy of Toronto Reference Library

When launched on 12 May 1842 (Fig. 5), the first issue of The Illustrated London News promised: “[t]he public will have henceforth under their glance, and within their grasp, the very form and presence of events as they transpire, in all their substantial reality, and with evidence visual as well as circumstantial” (“Our Address,” 1; my italics). As Maidment observes, “[s]uch an unequivocal yoking together of the wood-engraved image with realism had never been asserted so forcefully before, and the Illustrated London News capitalized heavily on this assumption, making wood engraving synonymous with claims for documentary accuracy in reportage” (Illustrated London News). Significantly, in this initial Address, it is the multiple prints themselves that guarantee authenticity: the eye (glance) and hand (grasp) of the ILN reader appears to have unmediated access to “substantial reality.” Fifteen years after this inaugural announcement, readers following reportage on the Indian Mutiny had been trained in viewing wood-engraved images in The Illustrated London News as authentic representations of human bodies, actions, and events.

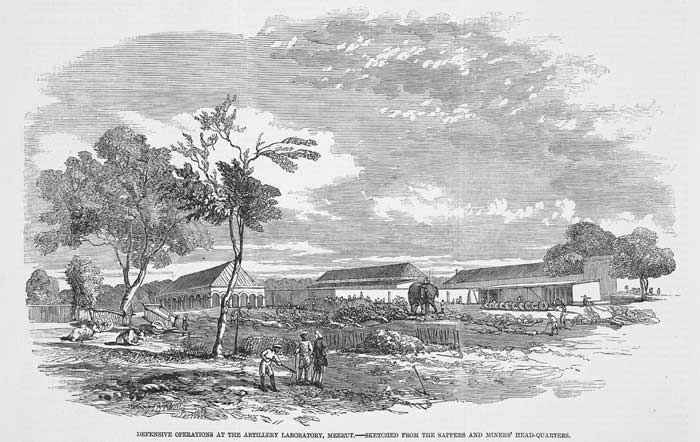

Figure 6: “Defensive Operations at the Artillery Laboratory, Meerut.—Sketched from the Sappers and Miners’ Head-quarters,” _The Illustrated London News_ 875 (22 August 1857): 192. Courtesy of Toronto Reference Library

August 1857

It was not, however, until 22 August 1857—three months after the rebellion erupted—that the ILN was able to publish its first wood-engraved illustrations after drawings created on location by British observers in India. Thus, there was always a time lag between articles based on telegraphed information and illustrations arriving later, with more detailed stories, by mail. In this watershed issue of Saturday 22 August, the ILN published a picture representing the “Defensive Operations at the Artillery Laboratory, Meerut” (Fig. 6), together with two related engravings and a recapitulation of the revolt that had occured on 10 May, all under the common title, “The Mutiny in India” (192-93). This visual/verbal reminder of the events surrounding the initial insurrection appeared in print just as the British public was reeling from news recently received of the massacre at ![]() Cawnpore through the apparent betrayal of the rebel leader, Nana Sahib. The publication of “Defensive Operations at the Artillery Laboratory, Meerut” at precisely this moment must have been laden with emotional impact for contemporary readers, innocuous as the image may seem to us. Apparently sketched by a civil servant on location, the picture shows elephants and their native handlers tearing up trees in order to build up the buffers of defense around the compound. Invisible, except to the ILN reader/viewer’s imagination, are the women and children placed for safety in the depicted Meerut artillery laboratory. Nevertheless, the picture and accompanying story recording the successful protection of British civilians on 10 May, must have implied a sad contrast to the more recent reports of Cawnpore, where women and children were allegedly massacred and thrown down a well on 15 July.

Cawnpore through the apparent betrayal of the rebel leader, Nana Sahib. The publication of “Defensive Operations at the Artillery Laboratory, Meerut” at precisely this moment must have been laden with emotional impact for contemporary readers, innocuous as the image may seem to us. Apparently sketched by a civil servant on location, the picture shows elephants and their native handlers tearing up trees in order to build up the buffers of defense around the compound. Invisible, except to the ILN reader/viewer’s imagination, are the women and children placed for safety in the depicted Meerut artillery laboratory. Nevertheless, the picture and accompanying story recording the successful protection of British civilians on 10 May, must have implied a sad contrast to the more recent reports of Cawnpore, where women and children were allegedly massacred and thrown down a well on 15 July.

In terms of wood-engraved prints, visual culture, and ideological discourse, 22 August 1857 was also a critically important publication date at the offices of the comic magazine, Punch. Unlike the Illustrated London News, Punch did not claim documentary realism for its illustrations. Rather, the Large Cut, or central political cartoon, interpreted the most significant events of the week, as reported in the Times. Here the visual tradition of caricature, rather than graphic realism, demonstrates the role played by wood-engraved prints in forming and influencing public opinion. Extremely popular with readers, the Large Cut (a pun on technological method and satiric means), “represented,” as Patrick Leary comments, “Punch’s claim to a kind of serious influence, rooted in allegory and addressing prominent public issues and events” (35). For nearly half a century, John Tenniel (also known for his illustrations of Lewis Carroll’s Alice in Wonderland), drew the political cartoon that formed the center of the magazine’s weekly issues. Surely the most famous political cartoon of Tenniel’s long career was the Large Cut—actually, a double-page fold-out illustration—published on 22 August 1857, in response to news of the massacre at Cawnpore.

Figure 7: John Tenniel, “The British Lion’s Vengeance on the Bengal Tiger,” _Punch_ 33 (22 August 1857): 76-77

Entitled “The British Lion’s Vengeance on the Bengal Tiger,” the print depicts the landscape of the subcontinent, with the king of beasts leaping on a tiger who has struck down a woman and infant (Fig. 7). The image, which was copied, imitated, reproduced, and disseminated far beyond the Punch issue, provides us with a material trace of a national response with international impact. At this late date, in our own digital, televisual, and cinematic visual culture, it is difficult to grasp the social effect a wood-engraved print in a weekly magazine could have. However, as Frankie Morris’s research has shown, “[t]he cut was taken up as a symbol of retribution, was reproduced on banners (as shown in Tenniel’s double-page cut of the week following), and was so effective that. . . the authorities feared that public opinion might force them into measures more extreme than those they were prepared to take.” The image soon made its way from print to performative venues of visual culture. The Standard Theater’s Christmas pantomime that year concluded with “all parties . . . entrapped in Punch’s picture of ‘The British Lion attacking the Bengal Tiger,’ headed ‘Caught at Last.’” By early 1858 The Illustrated London News could declare that a copy of Tenniel’s “noble engraving” from Punch “is in every household” (Morris 63), a formative part of everyday life and national opinion in a tumultuous year.

If the Punch Large Cut for 22 August 1857 became emblematic of the Indian Mutiny and British national feeling, it also came to represent the pinnacle of the artist’s achievement in 50 years of black-and-white illustration. In 1911, when an interviewer from the Daily Telegraph, congratulating a blind Tenniel on his 91st birthday, turned the talk to his career, he immediately adverted to the iconic cartoon: “‘I should like to ask you now, Sir John, whether you did not feel a savage thrill when you drew ‘The British Lion’s Vengeance on the Bengal Tiger’.” Tenniel’s reply is illuminating: ‘‘‘Well, perhaps I did; but you see it was all in a week’s work. Yet I recollect, now that you mention it, that I was interpreting the feeling that swayed us all at that stirring time’” (“Sir John Tenniel”). Neither artist nor reporter noted the slippage transposing “savagery” from Indian miscreants to British patriot. The nostalgic retrospective highlights the Punch print’s contradictory status within the ideological formations of Victorian visual culture: savage and noble, multiple and unique, popular cartoon and national art treasure.

As reported by the Daily Telegraph, Tenniel’s memory of the textual event highlights some of the key features of wood engraving in 1857 that this essay is exploring. Significantly, the drawing “was all in a week’s work” for the artist. One of the 2,300 political cartoons Tenniel drew on the woodblock for engraving and publication in Punch,[9] “The British Lion’s Vengeance on the Bengal Tiger” came out of an industrial economy of competitive newspaper production and circulation. Rather than a decision in the artist’s purview, as in the illustrations for the Moxon Tennyson, the subject of the political cartoon was determined in lengthy debate by staff around the Wednesday night Punch table—a debate that necessarily considered commerce and readership as well as national opinion. As Punch co-founder and editor Mark Lemon recalled, “although as a rule funny Large Cuts sold best, a ‘fighting cut’ like the ‘Bengal Tiger’ could boost circulation considerably” (qtd. in Leary 43). Readers, therefore, were also collaborators, both as consumers and as part of the mass “feeling” or public opinion that Tenniel and the Punch staff aimed to interpret, but also helped to shape. Yet while alluding to the commercial concerns of mass distribution, the Telegraph article simultaneously situates Tenniel’s memorable Large Cut within an artistic discourse first signaled by the Illustrated London News. Displayed in “every household,” the Punch cartoon is a “noble engraving,” a cherished work of art—perhaps even a national treasure—by the illustrator who was the first Briton to be knighted for black-and-white work of this kind.

If, thanks to the liminal status yet ubiquitous presence of wood engraving in 1857, the lines between art and industry were far from clear, the lines of power could also shift. Notably, despite its caption—“The British Lion’s Vengeance on the Bengal Tiger”—Tenniel’s cartoon does not actually accord immediate victory to the king of beasts. Rather, the drawing represents the lion’s attack in mid-flight, and the two adversaries appear almost equally matched. With the outcome of the rebellion still uncertain in August 1857, such an image was, perhaps, politic if not prescient. Nevertheless, if the winner is unclear in the Punch interpretation of events, what is at stake is not: white middle-class motherhood and all the patriotic sanctities this domestic icon represents for the British nation. Lying under the tiger’s paws, the inert bodies of a half-naked woman and baby imply that British values have been ravaged by savage ferocity.

In this interpretation of public feeling, the Punch cut registers contemporary nationalism, paternalism, and racism. The allegorical roles line up according to deeply inscribed black-and-white values: the noble British avenger, the savage native violator, the victimized and helpless mother and child. However, if the “noble engraving” is taken off the wall of the Victorian household, removed from our 21st-century gallery of historical prints, and returned to its actual context within the Punch issue for 22 August 1857, another narrative emerges. Less focused on black/white racial divisions at the edge of the empire, this story is colored by male/female gender relations within British patriarchal culture. In this scenario, the white middle-class woman no longer represents purity, frailty, and innocence abroad, but rather a clear and present danger to the power and authority of British men at home. Contemporary masculine anxiety about the agitation for women’s rights was metonymically captured in the popular press in the visual image of the crinoline—the skirt that took up more public space than a woman had any right to take.

The issue featuring the virile British Lion in its Large Cut also reports, in “Punch’s Essence of Parliament,” on the passing of the Matrimonial Causes Act in the House of Lords on Thursday 13 August 1857. (On the Matrimonial Causes Act, see Kelly Hager, “Chipping Away at Coverture: The Matrimonial Causes Act of 1857.″) “The more Mr. Punch reflects,” according to the collective editorial voice ventriloquized through the magazine’s iconic figure, “the more convinced he is that Woman is the great impediment to man’s living in peace and amity with his fellow man” (“Punch’s Essence of Parliament” 71). This reflection would not have been a surprise to the Victorian reader. Throughout 1857, Punch was vigorously engaged in lampooning “Crinolineomania,” a means of attacking the emerging women’s rights movement through the visual image of female fashion. As Julia Thomas points out, “Punch seems to have perceived the crinoline as a threat, and one, moreover, that was never separate from questions of female education and emancipation” (Pictorial Victorians 80). Significantly, in Tenniel’s Large Cut for 22 August 1857, the victimized body representing violated British womanhood is not wearing a crinoline; her outer garments appear to have been shredded, leaving her with minimal covering. However, in the pages surrounding the Large Cut, image and text repeatedly use the comic trope of the crinoline to attack middle-class women’s pretensions to power and authority. Indeed, Punch even plays this card in conjunction with references to the military engagement in India, where peace and amity did not appear to depend on the absence of women.

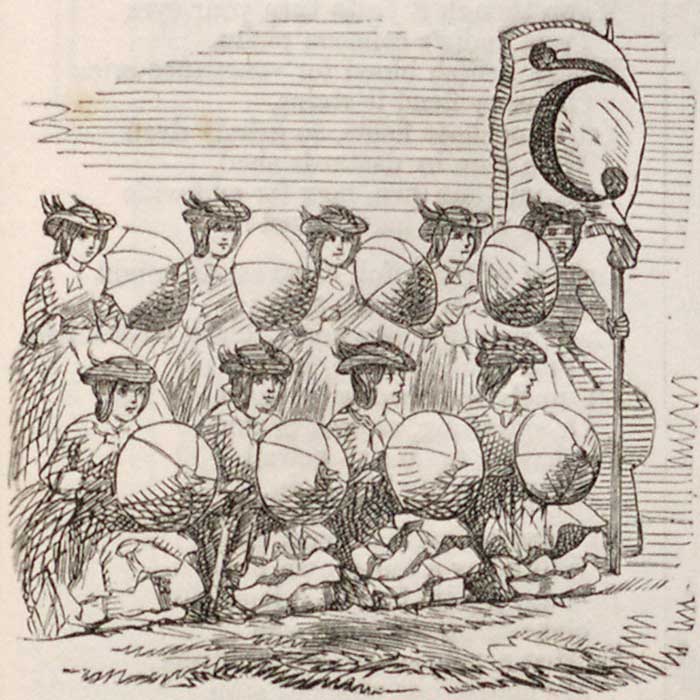

Figure 8: “Our National Defences,” _Punch_ 33 (22 August 1857): 79. Courtesy of Pratt Library, Victoria University, Toronto.

Immediately after “The British Lion’s Vengeance on the Bengal Tiger” is a long article headed by an inset wood engraving titled “Our National Defences” (Fig. 8).[10] Depicting an army of crinolined women using parasols as shields, the decorated capital (a “T” flying on the women’s banner) introduces a topical news item, beginning: “The drafting of some thirty thousand troops for India has, of course, revived the cry about our national defencelessness. . . .” This allusion to an actual danger then moves into Mr. Punch’s tongue-in-cheek proposal that “England should rely on the protection of its women. Encased as they are now in whalebone and in steel, they are thoroughly well armed to act on the defensive, and surrounded by their wide circumference of petticoat, it is clear that they are quite secure from close attack” (“Our National Defences” 79). The default mode of misogynist satire blinds Mr. Punch to the ironic relationship between Crinelomania and Cawnpore, where British women’s skirts had not secured them from close attack. Juxtaposed to “The British Lion’s Vengeance on the Bengal Tiger” on the previous page, and to the newspaper reports about the violent deaths of middle-class British women that the Large Cut referenced, Punch’s satire in “Our National Defences” carves out some of the ideological fissures and faultlines confronting readers in 1857.

October 1857

All through the summer and autumn months of 1857, periodicals were conveying news of events in India, together with debates on the rights of women, critiques of female fashion, reports on the Art Treasures of the United Kingdom Exhibition, and reviews of performances, such as the Christy Minstrels at ![]() St. James’s Theater. This miscellany of topical reading matter and wood-engraved prints from 1857 provides a rich context for our return to the Moxon Tennyson as a textual event in its own historical moment. With its nationalist themes, focus on female subjects, and incidental orientalism, the collection’s Pre-Raphaelite pictures emerge as much more than the launch of a new illustrative style by an avant-garde group of artists. In the context of its own time and place, the black-and-white lines of letterpress and engraving are ineluctably caught up in “the inscription of values in word and image” (Thomas) circulating in Victorian print and visual culture.

St. James’s Theater. This miscellany of topical reading matter and wood-engraved prints from 1857 provides a rich context for our return to the Moxon Tennyson as a textual event in its own historical moment. With its nationalist themes, focus on female subjects, and incidental orientalism, the collection’s Pre-Raphaelite pictures emerge as much more than the launch of a new illustrative style by an avant-garde group of artists. In the context of its own time and place, the black-and-white lines of letterpress and engraving are ineluctably caught up in “the inscription of values in word and image” (Thomas) circulating in Victorian print and visual culture.

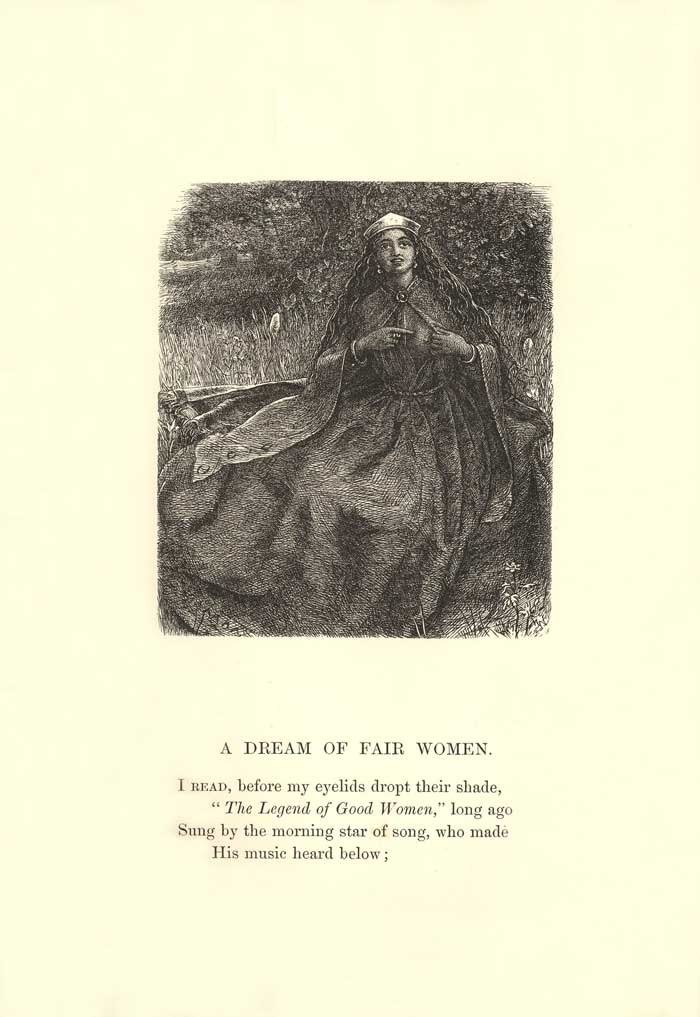

George Meredith’s omnibus essay in The Westminster Review in October 1857 highlights how a reader could inscribe contemporary ideologies of race and gender in the black-and white illustrations for Tennyson’s Poems. While noting the generally negative public reception (and poor sales) of the Moxon Tennyson, Meredith follows Ruskin’s lead in praising the unconventional and thought-provoking art of “the three chiefs of the pre-Raphaelites” (590). A prevailing orientalism, heightened by months of reportage on current events in India, illuminates his readings of the book’s “eastern” images, including Hunt’s for “Recollections of the Arabian Nights” (Figs. 9 and 10) and Millais’s for “A Dream of Fair Women” (Fig. 11).

Figure 9, Left: William Holman Hunt. “Recollections of Arabian Nights.” In Alfred Tennyson, _Poems_. Illustrated (1857). London: Moxon, 1859, 13. Private Collection, used with permission. Figure 10, Right: William Holman Hunt. “Recollections of the Arabian Nights.” In Alfred Tennyson, _Poems_. Illustrated (1857). London: Moxon, 1859, 19. Private Collection, used with permission

Figure 11: John Everett Millais, “Cleopatra,” for “A Dream of Fair Women.” In Alfred Tennyson, _Poems_. Illustrated. (1857). London: Moxon, 1859, 149. Private Collection, used with permission

Although Meredith purports to assess the illustrations on aesthetic grounds, as meet companions to Tennyson’s “exquisitely pictorial” art, he actually holds them to the standard of journalistic truth in reportage—that is, visual accuracy inscribed in wood-engraved lines, authenticated by on-location knowledge. According to these standards, Hunt succeeds, where Millais fails. Attributing an element of documentary realism to the former, Meredith claims that in Holman Hunt’s “Recollections of the Arabian Nights,” “Oriental Kief is given with the hand of one who knows the East. We wish he had made us a present of the Persian girl as well” (591). Enhancing Hunt’s images of Oriental langor and luxury with the two elements needed to complete the stereotype—kief (marijuana) and a female beauty with “argent-lidded eyes /Amorous” (Tennyson 18)—Meredith credits these illustrations by Hunt, who had traveled in the middle east, with the stamp of the eye-witness report, simultaneously underscoring the role played by the Orient in the Victorian erotic imaginary.

Although Meredith mourns the absence of the Persian girl from the collection of female subjects in the Pre-Raphaelite illustrations for Tennyson’s Poems, he objects strongly to the actual representation of another middle-eastern beauty: Cleopatra (Fig. 11). Without noting the irony of his critique, Meredith faults the black-and-white wood engraving of Millais’s design for “A Dream of Fair Women” for its representation of skin color. The illustration shows the Queen of ![]() Egypt in the dramatic act of applying the asp to “[t]he polish’d argent of her breast” (Tennyson 156). Perhaps in tribute to Tennyson’s intertext, Chaucer’s Legend of Good Women, Millais depicts Cleopatra sitting in an English grove wearing a vaguely medieval costume, rather than in a desert scene attired in robes associated with the last pharaoh of Ancient Egypt. However, it is not the anachronistic costume or landscape of Millais’s Cleopatra, but rather her dark face, that Meredith cites as inauthentic. This is despite the fact that the artist’s representation clearly responds to the poet’s description of the queen’s “flashing. . . smile,” “swarthy cheeks and bold black eyes” (Tennyson 155).

Egypt in the dramatic act of applying the asp to “[t]he polish’d argent of her breast” (Tennyson 156). Perhaps in tribute to Tennyson’s intertext, Chaucer’s Legend of Good Women, Millais depicts Cleopatra sitting in an English grove wearing a vaguely medieval costume, rather than in a desert scene attired in robes associated with the last pharaoh of Ancient Egypt. However, it is not the anachronistic costume or landscape of Millais’s Cleopatra, but rather her dark face, that Meredith cites as inauthentic. This is despite the fact that the artist’s representation clearly responds to the poet’s description of the queen’s “flashing. . . smile,” “swarthy cheeks and bold black eyes” (Tennyson 155).

In keeping with nineteenth-century Euro-centric traditions of representation, whose logic decreed that the Ancient Egyptians must have been Caucasian or they could never have built their civilization (Nelson 50), Meredith, in common with other contemporary art critics, “could not see aesthetic beauty in black features” (Marsh 15). Arguing that “Cleopatra was a daughter of Ptolemy, a Greek; and [that] the Egyptian climate would never have burnt and burnished her white blood to anything like the extent insisted upon by the artist,” Meredith complains: “She is absolutely made to point with a black finger to a black breast, which no sensible aspick [sic] would touch. . . . Mr. Millais has, moreover, made her expose her teeth—doubtless to get a little light into his drawing; but it wears the aspect of a curious case of insistence, as if the glorious beauty must not only be black like Dinah, but grin in sisterhood” (592). Recognizing that a wood-engraving can only show color by means of fine parallel lines and cross hatches in relative distances from each other, and in contrast to the dug-out “whites” left un-inked on the woodblock, Meredith nevertheless condemns the black-and-white print for its representation of skin tone. In aligning Millais’s Queen of Egypt with the stereotypical “Dinah,” a slang term for a black woman or servant, and the stock character of minstrel shows,[11] Meredith simultaneously associates Millais’s art with the traditions of popular culture and denies his dark subject any royal beauty. To be beautiful, Cleopatra must be white—a technical impossibility, in wood engraving as in life.

Tellingly, the black-and-white lines of Millais’s illustration confirm an entrenched stereotype for the observer. For a portrait of Cleopatra, the guarantee of authenticity cannot be eye-witness testimony; it can only rest on representation itself—literally, on multiples generated out of multiples, on copies rather than originals. “Historic and intuitive evidence,” the reviewer assures artist and reader, “tells us that the Serpent of old ![]() Nile was fair. The most destructive women are always fair” (Meredith 592). Hovering behind this critic’s evaluation of Millais’s Cleopatra is the misogynist attitude recorded in Punch attributing the destruction of masculine peace to fair British women. But also discernible is the image of the abject black woman, the de-sexualized, comic figure of the standard minstrel show, then playing to popular acclaim in London. After eight years of success in New York, the Christy Minstrels opened in

Nile was fair. The most destructive women are always fair” (Meredith 592). Hovering behind this critic’s evaluation of Millais’s Cleopatra is the misogynist attitude recorded in Punch attributing the destruction of masculine peace to fair British women. But also discernible is the image of the abject black woman, the de-sexualized, comic figure of the standard minstrel show, then playing to popular acclaim in London. After eight years of success in New York, the Christy Minstrels opened in ![]() St. James’s Theater on 3 August 1857, where they entertained audiences for the next twelve months with song, dance, and comic dialogue.[12] Images of the minstrels and their stock characters circulated throughout print culture that year in multiple forms, from wood-engraved prints to photographs, jostling with contemporary anti-slavery posters and broadsides for representation of the black face (Fig. 12).

St. James’s Theater on 3 August 1857, where they entertained audiences for the next twelve months with song, dance, and comic dialogue.[12] Images of the minstrels and their stock characters circulated throughout print culture that year in multiple forms, from wood-engraved prints to photographs, jostling with contemporary anti-slavery posters and broadsides for representation of the black face (Fig. 12).

Figure 12: Photograph, Minstrel Show Performers Rollin Howard (in wench costume) and George Griffin, c. 1855

The Moxon Tennyson was printed in 10,000 copies in its first edition. In order to preserve the original woodblocks from the wear and tear such multiple printings might cause, they were, as were most boxwood blocks in the second half of the century, duplicated using a process of electrolysis that created metal facsimiles. In other words, the illustrations of the Moxon Tennyson were printed from electrotypes, or what we conventionally call “stereotypes”—a term that actually refers to an earlier technology for making facsimiles of woodblocks from moulds rather than electrical processes—that is, the systemic, widespread reproduction of preformed conceptions. While we may no longer grasp the stereotypes that literally constructed beauty, victimization, predation, comedy, or violence in Victorian wood engravings, we can read some of their complex ideological formations when we examine them in context. As J. Hillis Miller observes, if we read images and words separately, we miss “the meanings and forces generated by their adjacency” (9). As I hope I have shown, the technology of reproduction is also crucially important to what we see, and how we see it. In addition to the adjacency of image and words, we need to be alert to the adjacency of events and the ways in which these were represented and circulated to Victorian readers.

Nevertheless, as technologies change, so too do structures of representation and ways of seeing and knowing. Dear Reader, you are scanning this article in pixels on a screen, and the images and texts it reproduces are not only adjacent to, and juxtaposed against, other images and texts on the BRANCH timeline, but also enmeshed in the virtually infinite representations of the World Wide Web. Although we can never see with the eyes of 1857, or grasp our Victorian pages with the hands of 1857, reading words and images in their “now-time” of reception, and understanding the social, technological, and material conditions of their production, allows us to glimpse into the forces that shaped them and the meanings that branched out of them. Each of the textual events I have been tracing through the black-and-white lines of Victorian wood engraving, so different in kind, impact, and duration, is not simply a node on a timeline, but rather a network of associations traveling through time and space—textual events whose outcomes are still in process, and whose reverberations continue to touch our lives.

published January 2013

HOW TO CITE THIS BRANCH ENTRY (MLA format)

Kooistra, Lorraine Janzen. “The Moxon Tennyson as Textual Event: 1857, Wood Engraving, and Visual Culture.” BRANCH: Britain, Representation and Nineteenth-Century History. Ed. Dino Franco Felluga. Extension of Romanticism and Victorianism on the Net. Web. [Here, add your last date of access to BRANCH].

WORKS CITED

Anderson, Patricia. The Printed Image and the Transformation of Popular Culture 1790-1860. Oxford: Clarendon, 1991. Print.

Benjamin, Walter. “The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction.” The Nineteenth-Century Visual Culture Reader. Ed. Vanessa R. Schwartz and Jeannene M. Przyblyski. New York: Routledge, 2004. 63-72. Print.

B. W. W. “The Christy Minstrels.” Rev. Theatrical Journal 19.975 (August 1858): 262. British Periodicals Database, C19: The Nineteenth Century Index. Pro-Quest. Web. 9 July 2012.

Cassell, John. John Cassell’s Art Treasures Exhibition: Containing Engravings of the Principal Masterpieces of the English, Dutch, Flemish, French, and German Schools, with Biographical Sketches of the Painters, and Critical Notices of Their Production. London: W. Kent, 1858. Print.

“Christy’s Minstrels.” Rev. Musical Gazette 2.32 (8 August 1857): 377. British Periodicals Database, C19: The Nineteenth Century Index. Pro-Quest. Web. 9 July 2012.

Curtis, Gerard. Visual Words: Art and the Material Book in Victorian England. Aldershot: Ashgate, 2002. Print.

Dalziel, Edward and George Dalziel. The Brothers Dalziel: A Record 1840-1890. London: Methuen, 1901. Rept. London: B.T. Batsford, 1978. Print.

Goldman, Paul. Victorian Illustrated Books 1850-1870: The Heyday of Wood-engraving. London: British Museum, 1994.

Kooistra, Lorraine Janzen. Poetry, Pictures, and Popular Publishing: The Illustrated Gift Book and Victorian Visual Culture 1855-1875. Athens: Ohio UP, 2011. Print.

Leary, Patrick. The Punch Brotherhood: Table Talk and Print Culture in Mid-Victorian London. London: The British Library, 2010. Print.

Maidment, Brian. The Illustrated London News. Dictionary of Nineteenth-Century Journalism. C19: The Nineteenth Century Index. Ed. Laurel Brake and Marysa Demoor. Pro-Quest LLC. Web. 8 June 2012.

—. Reading Popular Prints 1790-1870. Manchester: Manchester UP, 2001. Print.

“Our National Defences.” Punch 33 (22 August 1857): 79. Print.

“Punch’s Essence of Parliament.” Punch 33 (22 August 1857): 71. Print.

Marsh, Jan, ed. Black Victorians: Black People in British Art 1800-1900. Aldershot: Lund Humphries, 2005. Print.

[Meredith, George]. “Belles Lettres and Art.” The Westminster Review 68.134 (October 1857): 585-604. C19 Index of British Periodicals. 2008 ProQuest LLC. Web. 24 June 2012.

Miller, J. Hillis. Illustration. Cambridge, MA: Harvard UP, 1992. Print.

Mitchell, Sally. Victorian Britain: An Encyclopedia. New York: Garland, 1988. Print.

Morris, Frankie. Artist of Wonderland: The Life, Political Cartoons, and Illustrations of Tenniel. Charlottesville: U of Virginia P, 2005. Print.

Nelson, Charmaine. “Vénus Africaine: Race, Beauty and African-ness.” Black Victorians: Black People in British Art 1800-1900. Ed. Jan Marsh. Aldershot: Lund Humphries, 2005. 46-56.

“Our Address.” Illustrated London News 1.1 (Saturday May 14th, 1842): 1. Print.

Reid, Forrest. Illustrators of the Eighteen Sixties: An Illustrated Survey of the Work of 58 Artists (1928). New York: Dover, 1975. Print.

Rossetti, Dante Gabriel. Correspondence of Dante Gabriel Rossetti. Vol. II. The Formative Years, 1855-1862. Ed. William E. Fredeman. Cambridge: D.S. Brewer, 2002. Print.

Ruskin, John. The Elements of Drawing. (1857). Intro. by Lawrence Campbell. New York: Dover, 1971. Print.

Sinnema, Peter W. Dynamics of the Printed Page: Representing the Nation in The Illustrated London News. Aldershot: Ashgate, 1998. Print.

“Sir John Tenniel, who celebrated his 91st birthday yesterday.” Photo and story excerpted from The Daily Telegraph and inserted beside “The British Lion’s Vengeance on the Bengal Tiger” from 22 August 1857, copy of Punch 33 held in the Pratt Library, University of Toronto, Special Collections. Print.

Tenniel, John. “The British Lion’s Vengeance on the Bengal Tiger.” Punch 33 (22 August, 1857): 64. Print.

Tennyson, Alfred. Poems. Illustrated. (1857). Facs. London: Scolar, 1976. Print.

“The Mutiny in India.” Illustrated London News 875 (22 August 1857): 192-93. Print.

Thomas, Julia. Pictorial Victorians: The Inscription of Values in Word and Image. Athens: Ohio UP, 2004. Print.

White, Gleeson. English Illustration: “The Sixties”: 1855-70. (1897). Bath: Kingsmead Reprints, 1970. Print.

Wood, Marcus. “Minstrelsy and the ‘Ethiopian’ and ‘Nigger’ songsters.” The Poetry of Slavery: An Anglo-American Anthology 1764-1865. Ed. Marcus Wood. Oxford: Oxford UP, 2003. 685-93.

RELATED BRANCH ARTICLES

Morna O’Neill, “On Walter Crane and the Aims of Decorative Art”

Joseph Viscomi, “Blake’s Invention of Illuminated Printing, 1788″

ENDNOTES

[1] See Brian Maidment for a history of the traditions of caricature and realism in Victorian prints, and an analysis of their respective codes of communication and associated ideological values.

[2] Literary illustration in both books and periodicals has, of course, a long history of its own representational strategies and conventions; to rehearse this history exceeds the scope of this paper, which takes as its starting point the generally accepted view that the Pre-Raphaelite approach to illustration in the Moxon Tennyson signaled a new departure in pictorial interpretation of poetry.

[3] In addition to Dante Gabriel Rossetti, the Oxford Union Debating Hall murals were painted by the young William Morris and Edward Burne-Jones, among others.

[4] Although originally intended for Christmas sales, the illustrated Poems missed its market by some months, owing to delays to the publisher’s production schedule occasioned by the illustrations.

[5] For a fascinating analysis of the British Library Reading Room in relation to Victorian visual culture, see Gerard Curtis, Visual Words: Art and the Material Book in Victorian England.

[6] As is well known, Tennyson’s illustrated Poems did not sell well or immediately achieve critical acclaim when issued by Moxon. However, when issued by Routledge the following Christmas of 1858, the book sold well as a guinea gift-book, and continued to do so for the next decade; by 1860 it was already being hailed by critics as the benchmark for wood-engraved book illustration. For more details, see Lorraine Janzen Kooistra, Poetry, Pictures, and Popular Publishing: The Illustrated Gift Book and Victorian Visual Culture 1855-1875.

[7] For a detailed discussion of Sir Joseph Noel’s famous easel painting on the subject of the Indian Mutiny, In Memoriam, in the context of Victorian visual culture, see Julia Thomas’s chapter in Pictorial Victorians.

[8] The Illustrated London News had a foreign correspondent /visual journalist based in ![]() Hong Kong who also sent in images based on Indian immigrants in that corner of the empire.

Hong Kong who also sent in images based on Indian immigrants in that corner of the empire.

[9] John Tenniel’s first cartoon appeared in Punch in 1851, and his last in 1901; in these five decades he produced a total of 2,300 woodblock designs (Morris 225).

[10] See Figs. 3 and 12 for contemporary images of women wearing skirts with crinolines at the Art Treasures Exhibition and (in drag) in minstrel shows.

[11] In “Minstrelsy and the ‘Ethiopian’ and ‘Nigger’ Songsters,” Marcus Wood reproduces some of the songs of minstrel shows; “De New York Nigger,” “Black Sam,” and “Long Time Ago” each refer to “Dinah.” As Wood observes, the “popular audience was a transatlantic one, and by the mid-nineteenth century the stars of North American minstrelsy, no less than the big stars of abolition, toured Britain” (685).

[12] Although the “Ethiopian Serenaders” had played in St. James’s Theater as early as 1846, August 1857 marks the first British performance of the Christy Minstrels, whose show was considered both more cultured and more authentic than the earlier troupe’s. As B. W. W.’s review for the Theatrical Journal recorded a year later, when the Minstrels were about to depart for a European tour: “It is not only the admiration of the general public that they can pride themselves upon having secured during their sojourn amongst us; persons of the highest rank in this country have been to witness their performances, and to appreciate them.” See also the review of the “Christy’s Minstrels” in the Musical Gazette of August 1857.