Abstract

The modern commercial art gallery emerged as a distinct institutional form in the middle years of the nineteenth century, profoundly changing the physical, economic and social relationships between artists, dealers, art objects, and viewers.

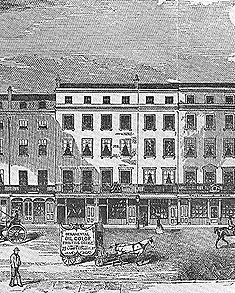

If you wanted to purchase a painting by a contemporary artist in London in 1789, you might have perused the annual exhibitions of the ![]() Royal Academy or other exhibition societies, or commissioned a work of art directly from the artist. You might also have examined a dealer’s stock, though art dealers at this time tended to sell imported Old Masters rather than the work of living British artists (Pears; Westgarth). If you wanted to purchase a painting by a contemporary artist in London in 1910, you still had all these options but you would most likely have visited a commercial gallery, a retail space exclusively dedicated to the display and sale of fine art. Over the course of the long nineteenth century, the commercial art gallery assumed its recognizably modern form: a permanent retail space with regular hours, which was associated with a dealer of acknowledged expertise, hosted a regular schedule of well-publicized temporary exhibitions, and was identified with a distinct specialization or brand. These attributes, however, emerged gradually and in an uneven pattern, only slowly consolidating into the form of the modern commercial art gallery. How, then, can the gradual emergence of a type be mapped onto the history of a timeline? On the one hand, it seems impoverishing even to attempt to do so: any instance the historian points to as the “first” example of something can be trumped by another historian’s claim to having found an earlier example. On the other hand, in 1789 there was no such thing as a commercial art gallery in London, and in 1910 there were hundreds of them.

Royal Academy or other exhibition societies, or commissioned a work of art directly from the artist. You might also have examined a dealer’s stock, though art dealers at this time tended to sell imported Old Masters rather than the work of living British artists (Pears; Westgarth). If you wanted to purchase a painting by a contemporary artist in London in 1910, you still had all these options but you would most likely have visited a commercial gallery, a retail space exclusively dedicated to the display and sale of fine art. Over the course of the long nineteenth century, the commercial art gallery assumed its recognizably modern form: a permanent retail space with regular hours, which was associated with a dealer of acknowledged expertise, hosted a regular schedule of well-publicized temporary exhibitions, and was identified with a distinct specialization or brand. These attributes, however, emerged gradually and in an uneven pattern, only slowly consolidating into the form of the modern commercial art gallery. How, then, can the gradual emergence of a type be mapped onto the history of a timeline? On the one hand, it seems impoverishing even to attempt to do so: any instance the historian points to as the “first” example of something can be trumped by another historian’s claim to having found an earlier example. On the other hand, in 1789 there was no such thing as a commercial art gallery in London, and in 1910 there were hundreds of them.

In this essay, I will explore the emergence and rise of the institutional form of the commercial art gallery through a set of three events that mark significant milestones in this process in the middle decades of the nineteenth century. Such a “timeline” could be extended, of course, beyond the boundaries of the long nineteenth century. Important precursors to the commercial gallery include artists’ exhibition societies that hosted annual shows, art and antiquity dealers, and print sellers and other retail traders who also exhibited paintings. And the twentieth and twenty-first centuries have given us the ideal of the gallery as “white cube” and the rise of the international art fair and biennial, all of which have made critical changes to the very concept of the commercial gallery. But in the middle years of the nineteenth century, a broad base of art consumers, an emerging set of new retail practices, an active periodical press, and a relative glut of artists and art works combined to create the conditions in which the recognizably modern form of the commercial art gallery came to be a viable, even necessary, part of the art market.

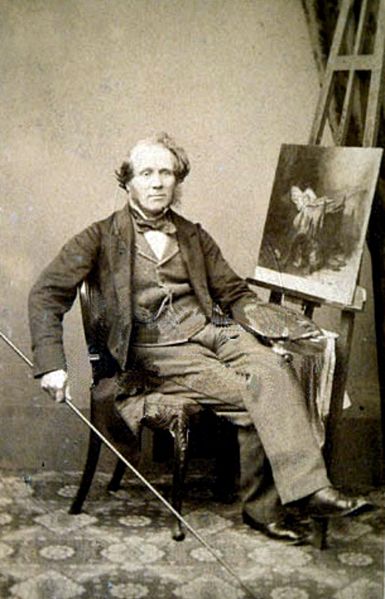

In April 1854, art dealer Ernest Gambart held the first annual “French Exhibition” in his gallery space atIn 1867, the Royal Academy officially decided to move from ![]() Trafalgar Square to more spacious premises at

Trafalgar Square to more spacious premises at ![]() Burlington House, holding the first annual exhibition in its new home in summer 1869. Almost as soon as the announcement was made, galleries that had clustered around Trafalgar Square and Pall Mall began to contemplate following suit. Once again, Gambart was a pioneer. In 1867, he sold the lease of the French Gallery to his manager Henry Wallis and moved his business to 22 Albemarle Street, near Burlington House. Over the course of the 1870s, Dickinson’s Gallery, the Doré Gallery, the Belgian Gallery, the Fine Art Society, L’Art Gallery, the Marine Picture Gallery, the Grosvenor Gallery, and Agnew’s all opened premises on

Burlington House, holding the first annual exhibition in its new home in summer 1869. Almost as soon as the announcement was made, galleries that had clustered around Trafalgar Square and Pall Mall began to contemplate following suit. Once again, Gambart was a pioneer. In 1867, he sold the lease of the French Gallery to his manager Henry Wallis and moved his business to 22 Albemarle Street, near Burlington House. Over the course of the 1870s, Dickinson’s Gallery, the Doré Gallery, the Belgian Gallery, the Fine Art Society, L’Art Gallery, the Marine Picture Gallery, the Grosvenor Gallery, and Agnew’s all opened premises on ![]() Bond Street, the heart of the luxury retail market. As the Goupil Gallery announced as they moved to the area in 1883, they “had long felt that the situation of their late Galleries [in

Bond Street, the heart of the luxury retail market. As the Goupil Gallery announced as they moved to the area in 1883, they “had long felt that the situation of their late Galleries [in ![]() the Strand] has been found too inconvenient to allow of their seeing their patrons so often as they would desire, and they trust that . . . their removal to the most famous of West-end thoroughfares, will insure to them . . . more frequent visits from their present numerous amateurs” (The Year’s Art 1883 5). These new spaces were grandly designed and elegantly appointed, aiming to attract a fashionable and wealthy clientele (Denney; Helmreich). As Henry James wryly noted about the fashionable

the Strand] has been found too inconvenient to allow of their seeing their patrons so often as they would desire, and they trust that . . . their removal to the most famous of West-end thoroughfares, will insure to them . . . more frequent visits from their present numerous amateurs” (The Year’s Art 1883 5). These new spaces were grandly designed and elegantly appointed, aiming to attract a fashionable and wealthy clientele (Denney; Helmreich). As Henry James wryly noted about the fashionable ![]() Grosvenor Gallery, “[i]n so far as his [Sir Coutts Lindsay, the proprietor] beautiful rooms in Bond Street are a commercial speculation, this side of their character has been gilded over, and dissimulated in the most graceful manner” (139). By the 1880s, the landscape of the gallery system had been firmly established in the West End, fostering a gallery culture of luxury and display.

Grosvenor Gallery, “[i]n so far as his [Sir Coutts Lindsay, the proprietor] beautiful rooms in Bond Street are a commercial speculation, this side of their character has been gilded over, and dissimulated in the most graceful manner” (139). By the 1880s, the landscape of the gallery system had been firmly established in the West End, fostering a gallery culture of luxury and display.

By the early years of the twentieth century, the Academy was widely seen to have lost its preeminent place in the art market, increasingly supplanted both economically and culturally by the gallery system. This was a change with profound effects for the relationships between artist, dealer, art object, and audience. The commercial art gallery provided new financial opportunities and challenges for artists and dealers and new kinds of physical and social spaces for viewers’ engagement with art (Fletcher and Helmreich). Over the twentieth and twenty-first centuries, the gallery system proved to be a resilient and adaptive form, evolving new standards of interior design, re-mapping the cultural geography of the urban art market, and adopting new marketing techniques in response to new forms of art and emerging audiences and technologies. Yet through all of these changes, the primary innovation of the 1850s and 1860s—the creation of a dedicated retail space managed by a professional dealer and hosting a series of rotating exhibitions—has endured as the entirely familiar form of the commercial art gallery.

HOW TO CITE THIS BRANCH ENTRY (MLA format)

published March 2012

Fletcher, Pamela. “On the Rise of the Commercial Art Gallery in London.” BRANCH: Britain, Representation and Nineteenth-Century History. Ed. Dino Franco Felluga. Extension of Romanticism and Victorianism on the Net. Web. [Here, add your last date of access to BRANCH].

WORKS CITED

Denney, Colleen. “The Grosvenor Gallery as Palace of Art: An Exhibition Model.” The Grosvenor Gallery: A Palace of Art in Victorian England. Ed. Susan P. Casteras and Colleen Denney. New Haven: Yale UP, 1996. 9-38. Print.

Fletcher, Pamela M. “Creating the French Gallery: Ernest Gambart and the Rise of the Commercial Art Gallery in Mid-Victorian London.” Nineteenth-Century Art Worldwide 6:1 (2007): n. pag. Web. 29 Dec. 2011.

Fletcher, Pamela, and Anne Helmreich, eds. The Rise of the Modern Art Market in London, 1850-1939. Manchester: Manchester UP, 2011. Print.

Frith, William Powell. My Autobiography and Reminiscences. Vol. 1. New York: Harper, 1889. Print.

Helmreich, Anne. “The Art Dealer and Taste: The Case of David Croal Thomson and the Goupil Gallery, 1885-1897.” Visual Culture in Britain 6:2 (2005): 31-49. Print.

James, Henry. “The Picture Season in London.” 1877. The Painter’s Eye: Notes and Essays on the Pictorial Arts. Ed. John L. Sweeney. Madison: U of Wisconsin P, 1989. 130-51. Print.

“Life at a Railway Station.” Art Journal May 1862: 122-3. Print.

Maas, Jeremy. Gambart: Prince of the Victorian Art World. London: Barrie and Jenkins, 1975. Print.

Millais, John Guille. The Life and Letters of Sir John Everett Millais. Vol. 1. New York: Stokes, 1899. Print.

“Minor Topics of the Month.” Art Journal Oct. 1862: 210. Print.

Pears, Iain. The Discovery of Painting: The Growth of Interest in the Arts in England 1680-1768. New Haven: Yale UP, 1988. Print.

The Year’s Art 1883. London: Low, Marston, Searle, and Rivington, 1883. Print.

Westgarth, Mark. “‘Florid-looking speculators in Art and Virtu’: The London Picture Trade c. 1850.” The Rise of the Modern Art Market in London, 1850-1939. Ed. Pamela Fletcher and Anne Helmreich. Manchester: Manchester UP, 2011. 26-46. Print.

RELATED BRANCH ARTICLES

Nicholas Frankel, “On the Whistler-Ruskin Trial, 1878″

Anne Helmreich, “On the Opening of the Crystal Palace at Sydenham, 1854″

Audrey Jaffe, “On the Great Exhibition”

Aviva Briefel, “On the 1886 Colonial and Indian Exhibition”

Amy Woodson-Boulton, “The City Art Museum Movement and the Social Role of Art”