Irena Yamboliev, “Christopher Dresser, Physiological Ornamentist”

This article argues that, in 1862, when he published his most influential book The Art of Decorative Design, Christopher Dresser joined the multi-disciplinary enterprise of the physiological aesthetics in the name of ornamental form, positioning the theory of ornament as a crucial cutting edge of the empirical study of human aesthetic responses. I read The Art of Decorative Design in relation to contemporary psychological-aesthetics texts by Alexander Bain, Herbert Spencer, James Sully, Edmund Gurney, and Clementina Anstruther-Thomson and Vernon Lee to show that Dresser finds in ornamental form a site for a materialist physiological understanding of aesthetic response—and he does so well prior to the essays on aesthetics that were published in the journal Mind from the 1870s on. Like contemporary empirical aestheticists—and in distinction to other ornamentists of his time—Dresser emphasizes the mental “laws” that orchestrate our reactions to forms in nature and in ornament alike. Tracing in Dresser’s design handbook an approach to ornamental form that becomes fully “physiologized” in Bain’s, Sully’s, Gurney’s, and Lee’s writing makes more complete the critical picture of the so-called “lesser” (and often pejoratively feminized) decorative arts as a fertile ground for the theories and practices the empirical aestheticists were pursuing.

Kristin Mahoney, “On the Ceylon National Review, 1906-1911″

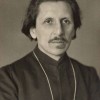

The Ceylon National Review (1906-1911) was the official organ of the Ceylon Social Reform Society, an organization founded by the art historian Ananda Coomaraswamy in an effort to combat colonial influence and reinvigorate Ceylonese cultural production. Coomaraswamy also served as an editor at the Ceylon National Review. This essay focuses on the manner in which Coomaraswamy, in the essays he contributed to and solicited for the journal, fostered transethnic Ceylonese nationalism and anticolonial resistance as well as transnational engagement with British countercultural movements and radical thought. Paying particular attention to Coomaraswamy’s interest in socialist aestheticism, Theosophy, and British discourses concerning vegetarianism, I foreground the highly cosmopolitan inflection of Coomaraswamy’s brand of Ceylonese nationalism as expressed in the pages of the Ceylon National Review. In the essays he wrote and selected for publication in the periodical, Coomaraswamy integrated the discourses of anticolonialism and socialist aestheticism and allowed British and Ceylonese vegetarians and Theosophists to speak in relation to one another, engendering a rich and surprising form of Ceylonese nationalism inflected by late-Victorian radicalism.

Jill R. Ehnenn, “On Art Objects and Women’s Words: Ekphrasis in Vernon Lee (1887), Graham R. Tomson (1889), and Michael Field (1892)”

Studies of women’s ekphrasis prior to modernism have, so far, tended to focus on individual women writers rather than attempt to identify trends that female authors from a particular time period might share. This essay intervenes in this gap in the scholarship by analyzing ekphrastic prose and poetry by Vernon Lee, Graham R. Tomson, and the co-authors who wrote as Michael Field. As female Aesthetes well-versed in art history and art criticism, as well as contemporary market practices, these nineteenth-century women writers anticipate today’s feminist theorists in the ways in which they were quite conscious of woman’s role as art object and the various functions of that role.

Here I examine Vernon Lee’s somewhat well-known novella Amour Dure (1887) as a foundational case study and then turn to two considerably lesser studied poems: Graham R. Tomson’s “A Silhouette” (1889) and Michael Field’s “Saint Katharine of Alexandria” (1892), for which I also identify the long-lost ekphrastic referent. These three texts all demonstrate how a specific form of aesthetic intertextuality—ekphrastic representational friction—operates as a powerful vehicle for early feminist criticism. In the examples I discuss, gendered critiques drive representational friction between the word, the visual medium, and its original referent—slippages that these art-savvy authors would have easily recognized and had opinions about in the work of others, and intentionally created and/or appropriated in their own work. Importantly, I also argue that a helpful way to think about ekphrastic writing by women writers associated with nineteenth-century British Aestheticism is to consider representational friction with particular regard to how their texts treat objects—seemingly unimportant objects—associated with their subjects.

Rebecca N. Mitchell, “15 August 1862: The Rise and Fall of the Cage Crinoline”

First introduced to England by France’s Empress Eugénie in the late 1850s, the cage crinoline signaled a new era in fashion, reaching peak popularity (and peak circumference) in the early 1860s. While the garment has often been understood as a symbol of a repressive patriarchal order intent on confining women, contemporary reporting shows that it was regarded instead as a potentially threatening tool of emancipation. It replaced layers of heavy petticoats with a light and flexible alternative, offering women greater mobility and comfort, and the proportions of the skirts obviated the need for tight-laced corsets. What is more, donning crinoline allowed women to assert physical space in the public sphere, their voluminous skirts forcing men to the margins of the sidewalk or the omnibus—at least according to complaints. Perhaps the most pernicious quality of crinoline, though, was its potential to hide things from the male gaze: bad ankles or smuggled goods might be hidden by the cage, but the risk of concealed pregnancy loomed largest. Reports of death by crinoline fire were matched in their fevered pitch by warnings that crinoline sharply increased rates of infanticide. The range of Victorian responses that accrued around the fashion demonstrates that it was not simply a tool for unilateral oppression or reducible to the manifestation of empty, thoughtless vanity.

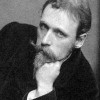

Morna O’Neill, “On Walter Crane and the Aims of Decorative Art”

Walter Crane (1845-1915) was one of the most important, versatile, and radical artists of the nineteenth century: a painter, decorator, designer, book illustrator, poet, author, teacher, art theorist, and socialist. As a synthesis of art, design, and politics, Crane’s career offers new insights into the tradition of painting, the status of the decorative arts, and the transgression of their boundaries at the end of the nineteenth century. His work provides an important, decorative alternative to a realist idiom for socialist art.

Ayla Lepine, “On the Founding of Watts & Co., 1874”

In 1874 three prominent Victorian architects founded the ecclesiastical and domestic fittings and furnishings business Watts & Company: George Gilbert Scott junior, Thomas Garner, and George Frederick Bodley. The firm was established within a cultural climate of transition. By the 1870s, the Gothic Revival and the Aesthetic Movement began to overlap and merge. Sacred and secular architectural and decorative impulses increasingly shared common traits. These aesthetic shifts were accompanied by major debates in British religious and political spheres. In the foundations of Watts and Company, beauty and labor were interlaced with religious controversy, political reform, and commercial ambition. Begun when William Morris’ own decorative arts firm, begun in 1861, underwent drastic restructuring, and in the same few months that Parliament debated High Anglican rituals, and church practices could land clerics in prison, Watts and Company’s incorporation was a bold move for the three architects. What had its roots in radicalism and avant-garde style set the tone for the establishment tastes by the end of the century

Imogen Hart, “On the Arts and Crafts Exhibition Society”

The first exhibition of the Arts and Crafts Exhibition Society made new and ambitious claims for the public significance of decorative art. This article analyses the innovations and methods of the Society while also examining the conflicting motivations and ideological tensions within it. Instead of seeing the Society as straightforwardly representative of the Arts and Crafts movement and the activities of William Morris, I consider how it fits into a broader history of Victorian art and design, revealing its relationships with the Royal Academy of Arts and the Schools of Art system for training industrial designers.