Abstract

Studies of women’s ekphrasis prior to modernism have, so far, tended to focus on individual women writers rather than attempt to identify trends that female authors from a particular time period might share. This essay intervenes in this gap in the scholarship by analyzing ekphrastic prose and poetry by Vernon Lee, Graham R. Tomson, and the co-authors who wrote as Michael Field. As female Aesthetes well-versed in art history and art criticism, as well as contemporary market practices, these nineteenth-century women writers anticipate today’s feminist theorists in the ways in which they were quite conscious of woman’s role as art object and the various functions of that role.

Here I examine Vernon Lee’s somewhat well-known novella Amour Dure (1887) as a foundational case study and then turn to two considerably lesser studied poems: Graham R. Tomson’s “A Silhouette” (1889) and Michael Field’s “Saint Katharine of Alexandria” (1892), for which I also identify the long-lost ekphrastic referent. These three texts all demonstrate how a specific form of aesthetic intertextuality—ekphrastic representational friction—operates as a powerful vehicle for early feminist criticism. In the examples I discuss, gendered critiques drive representational friction between the word, the visual medium, and its original referent—slippages that these art-savvy authors would have easily recognized and had opinions about in the work of others, and intentionally created and/or appropriated in their own work. Importantly, I also argue that a helpful way to think about ekphrastic writing by women writers associated with nineteenth-century British Aestheticism is to consider representational friction with particular regard to how their texts treat objects—seemingly unimportant objects—associated with their subjects.

When we think of literary and visual examples of nineteenth-century British Aestheticism, most likely what comes to mind are images of the female body as cultural signifier—of “Woman” as object of the gaze. We may think of Dante Gabriel Rossetti’s 1872 painting, Veronica Veronese, which Rossetti described as “chiefly a study of varied greens” (72.10). Or we may recall Albert Moore’s languishing Dreamers, John Waterhouse’s depictions of the Lady of Shalott, Edward Burne-Jones’s Pygmalion images, or the sinister eroticism of Aubrey Beardsley’s drawings for Oscar Wilde’s Salome.

However, in addition to producing countless examples of women as art, the Victorian fin de siècle, gave rise, as studies such as Hilary Fraser’s Women Writing Art History in the Nineteenth Century (2014) remind us, to significant numbers of women writing about art. Late nineteenth-century women such as Violet Paget (1856-1935), who wrote as “Vernon Lee,” Rosamund (Ball) Marriott Watson (1860-1911), whose pen names include “Graham R. Tomson,” and Katharine Harris Bradley (1846-1914) and Edith Emma Cooper (1868-1913), who wrote collaboratively as “Michael Field,” were, through their lives and texts, challenging existing notions about women’s abilities, roles, and sexuality. In their fiction, poetry, art criticism, and other essays, these female Aesthetes created new and radical commentary on aesthetics and art. Notably, in the process of authorship, these women often incorporated, or, indeed, made their organizing principle, the literary strategy of ekphrasis, what James Heffernan calls “the art of describing works of art, the verbal representation of visual representation” (3).[1] As with thinking about female art historians in the nineteenth century, studying Victorian women’s ekphrastic writing should help us better comprehend how Victorian women looked at and understood the world around them.

Largely, however, the study of Victorian women’s ekphrases still does not adequately explore the matter of how nineteenth-century women saw and perceived art and their world. Granted, scholars of ekphrasis have long acknowledged a gendered dynamic whereby ekphrastic texts generally represent a male spectator gazing upon a female body or feminized art object; and most also consider ekphrastic writing’s paragonal quality—a rivalry or antagonism between the “sister arts” of verbal and visual representation that is powerfully gendered as well. Heffernan, for instance, writes that the contest staged by ekphrasis “evokes the power of the silent image even as it subjects it to the authority of language. …male speech trying to control a female image” (1). But studies of women’s ekphrastic writing, especially prior to the twentieth century are scant.[2] Where such projects exist, they have tended to focus on individual authors such as Felicia Hemans,[3] Charlotte and Anne Brontë,[4] Elizabeth Siddal,[5] and Michael Field,[6] rather than attempt to identify commonalities among authors. This gap in nineteenth-century scholarship is curious, since it is well documented that the era of The Woman Question and of increasing numbers of women writers also saw an unprecedented rise in technologies of vision, growing awareness of the consequences of seeing and of the relationship between visibility and invisibility, and a reliance on visual culture that still greatly influences us today.[7] Are there traditional ekphrastic strategies—or variations thereon—that are particularly notable among Victorian women’s ekphrastic writing?

This essay presents case studies of three ekphrastic texts produced by late-Victorian women writers who were also affiliated with the Aesthetic movement. Vernon Lee, Graham R. Tomson, and Michael Field were each chosen for this project because they possessed an astute knowledge of art; all also seem to share the convictions of their contemporary, Christina Rossetti, in anticipating twentieth- and twenty-first-century feminist critiques of how “Woman” signifies more as fantasy and as an object of male desire and control than she does as a real person. In the well-known poem “In an Artist’s Studio” (1856, 1896), Rossetti criticizes the vampiric relation of the male artist to the female model, stating “he feeds upon her face by day and night,” and concluding that the artist sees her “Not as she is, but as she fills his dream” (ll. 9, 14). Indeed, within male Aesthetic circles, as Kathy Psomiades observes, femininity functions as the driving force “to manage the contradiction between artistic autonomy on the one hand and art’s necessary commodification on the other” (33). As female Aesthetes well-versed in art history and art criticism, as well as contemporary market practices, Vernon Lee, Graham R. Tomson and the co-authors who wrote as Michael Field, much like the earlier Christina Rossetti and later feminist theorists of the twentieth century such as Laura Mulvey and Griselda Pollock, were quite conscious of woman’s role as art object and the various functions of that role.[8]

Here I examine three ekphrastic texts where representational friction—a specific form of aesthetic intertextuality pertaining to slippages between the word, the visual medium, and/or the original referent—operates as a powerful vehicle for early feminist criticism. Since they were all well-acquainted with art and art history, Vernon Lee, Graham R. Tomson, and Michael Field would have easily recognized slippages between art objects and their original referents, and between art objects and textual renditions of them. As I will demonstrate, these women possessed and articulated strongly feminist opinions about such representational friction in the work of others; and they created and/or appropriated this kind of aesthetic intertextuality in their own writing in a manner that also critiques gendered norms and dynamics. My claim here is not that there is anything inherently gendered about representational friction or aesthetic intertextuality itself; rather, what I hope to illustrate is that representational friction is a particularly useful aesthetic and textual space in which to observe gendered assumptions and dynamics at play. Importantly, I will also argue that a helpful way to think about ekphrastic writing by women writers associated with British Aestheticism is to consider representational friction with particular regard to how their texts treat objects—seemingly unimportant objects—associated with their subjects.[9]

To begin, I turn to Michel Foucault’s famous essay on Diego Velázquez’s painting Las Meninas, where he demonstrates how two seemingly paradoxical truths about visual and verbal representation can coexist. On the one hand, Foucault writes of the impossible relation of language to painting: “[n]either can be reduced to the other’s terms; it is in vain that we say what we see; what we see never resides in what we say” (9). On the other hand, he does in fact conduct a lengthy, painstaking verbal analysis, and defends the usefulness of such an exercise by explaining: “[i]t is perhaps through the medium of this grey anonymous language, always over meticulous and repetitive because too broad, that the painting may, little by little, release its illumination” (10). The “illumination” or lesson Foucault teaches us via Las Meninas is quite useful for framing discussions of women’s ekphrastic writing.

Through his exploration of what he sees and how he writes about what he sees, Foucault’s analysis of this unusual painting performs an important point: how acts of representation organize the possible modes of orientation to the experience of seeing and perceiving. Matters of orientation, in turn, can crucially affect what is considered the object and theme of the painting, how symbolism and composition work in the painting, and the extent to which the spectator can experience a sense of inclusion and reciprocity through the act of looking. Importantly, Foucault’s ultimate focus in his writing about Las Meninas is to help us understand what is seemingly not in the painting. Foucault observes: “the profound invisibility of what one sees is inseparable from the invisibility of the person seeing” (16). For Foucault, the things that are simultaneously invisible yet function to organize the gaze in Velázquez’s painting are the king and his wife, the artist, and the spectator. For the purpose of my project, I invoke Foucault’s insights about invisibility in order to argue that representational friction in the ekphrastic writing of Vernon Lee, Graham R. Tomson, and Michael Field calls attention to and refuses the traditional invisibility of woman as spectator; calls attention to and refuses the invisibility, or rather, the erasures of woman/model as ekphrastic referent; and, specifically with the assistance of representations of objects with Aesthetic and/or gendered connotations, suggests a relationship between these erasures or “invisibilities.”

I. Books and Roses: Vernon Lee (1887)

My first example of late-Victorian women’s ekphrasis is the novella Amour Dure by Vernon Lee.[10] First published in Murray’s Magazine (1887), then in a collection titled Hauntings, Fantastic Stories (1890), Amour Dure is the tale of a disillusioned Polish scholar, Spiridion Trepka, who visits ![]() Italy to produce a history of

Italy to produce a history of ![]() Urbania. He finds himself increasingly and obsessively distracted by a three-hundred-year-old portrait of Medea da Carpi, an infamous woman of great intelligence and seductive charm, who “was put to death … at the age of barely seven and twenty, having, in the course of her short life, brought to a violent end five of her lovers” (Lee 50). Trepka, who tells his story in diary entries, becomes consumed with Medea’s history, searches tirelessly for images of her, falls in love with her, mysteriously begins to see her everywhere and, equally mysteriously, receives letters in her hand. He finds “in Medea the embodiment of all his unfulfilled desires,” which, as Christa Zorn argues, “are motivated both by sexual obsession and alienation from his national identity” (5). Upon Medea’s written instruction, Trepka hacks open a bronze statue of her last husband—the Duke who had ordered her execution long ago—and smashes the silver totem the Duke had placed within to protect his soul from her ghost. The story then closes abruptly with a shift of voice:

Urbania. He finds himself increasingly and obsessively distracted by a three-hundred-year-old portrait of Medea da Carpi, an infamous woman of great intelligence and seductive charm, who “was put to death … at the age of barely seven and twenty, having, in the course of her short life, brought to a violent end five of her lovers” (Lee 50). Trepka, who tells his story in diary entries, becomes consumed with Medea’s history, searches tirelessly for images of her, falls in love with her, mysteriously begins to see her everywhere and, equally mysteriously, receives letters in her hand. He finds “in Medea the embodiment of all his unfulfilled desires,” which, as Christa Zorn argues, “are motivated both by sexual obsession and alienation from his national identity” (5). Upon Medea’s written instruction, Trepka hacks open a bronze statue of her last husband—the Duke who had ordered her execution long ago—and smashes the silver totem the Duke had placed within to protect his soul from her ghost. The story then closes abruptly with a shift of voice:

Here ends the diary of the late Spiridion Trepka. The chief newspapers of the province of

Umbria informed the public that, on Christmas morning of the year 1885, the bronze equestrian statue of Robert I had been found grievously mutilated; and that Professor Spiridion Trepka of Posen, in the German Empire, had been discovered dead of a stab in the region of the heart, by an unknown hand. (Lee 58)

Among the many portraits of Medea that Amour Dure‘s narrator finds so fatally compelling, one stands out as the referent for Lee’s ekphrastic portrayal of Medea da Carpi. Just when Trepka thought he possessed knowledge of all of Medea’s portraits (and by extension, knowledge of her and hope of possessing her love), the scholar uncannily finds one more by surprise, exclaiming, “Bronzino never painted a grander one” (Lee 61). The description of Medea that follows clearly resonates with Agnolo Bronzino’s 1540 portrait of Lucrezia Panciatichi (see Figure 1), whose long gold necklace includes small plates inscribed with the words, “Sans fin amour dure.”[11] Trepka records that the central figure in the newly rediscovered portrait of Medea is

seated stiffly in a high-backed chair, sustained as it were, almost rigid, by the stiff brocade of skirts and stomacher, stiffer for plaques of embroidered silver flowers and rows of seed pearl. The dress is with its mixture of silver and pearl, a strange dull red, a wicked poppy-juice colour, against which the flesh of the long narrow hands with fringe-like fingers; of the long slender neck, and the face with the bared forehead, looks hard and round, like alabaster. The face is the same as in the other portraits; the same rounded forehead, with the short fleece-like, yellowish-red curls; the same beautifully curved eyebrows, just barely marked; the same eyelids, a little tight across the eyes; the same lips, a little tight across the mouth; but with a purity of line, a dazzling splendour of skin, and intensity of look immeasurably superior to all the other portraits.

She looks out of the frame with a cold, level glance; yet the lips smile. One hand holds a dull-red rose; the other, long, narrow, tapering, plays with a thick rope of silk and gold and jewels hanging from the waist; round the throat, white as marble, partially confined in the tight dull-red bodice, hangs a gold collar, with the device on alternate enameled medallions, “AMOUR DURE—DURE AMOUR.” (Lee 62)

This reference to Bronzino is an effective ekphrastic moment in the text. Lee’s description of the dress’s “wicked poppy juice colour” and emphasis on the facial features’ uncanny “tightness” reinforces the reader’s perception of Medea da Carpi as having the Siren’s mysteriously addictive charm—of Medea as timeless femme but also as typical of what Bram Djikstra describes as feminine evil at the fin de siècle.

Figure 1. Agnolo Bronzino. _Portrait of Lucrezia Panciatichi_ (c. 1540)

Galleria degli Uffizi, Florence

However, I contend that the function of this particular ekphrastic description within Lee’s novella is also a mediating one, with the more important underlying purpose of directing the reader’s attention to the text’s consistent engagement with another, similar, visual referent, one with stronger implications for cultural critique. I refer, of course, to Leonardo da Vinci’s La Gioconda [Mona Lisa], along with its famous ekphrastic commentary by Walter Pater. Here, my claims follow Zorn’s excellent argument that Lee’s novella is “an animated portrayal of ‘la Gioconda’ in Studies in the History of the Renaissance” (4).[12] My analysis uses Zorn as a jumping-off point from which to take a closer look at how what she calls “aesthetic intertextuality” functions in the specific context of ekphrastic representational friction between written text and image and original referent/model. This approach to representational friction in Lee’s ekphrastic critique of gender and aesthetics will, then, in turn, serve as a useful foundation from which to subsequently discuss Tomson and Field.

Lee’s verbal representation of the Bronzino painting is a veritable ekphrastic tapestry that weaves a path, to scathing effect, through the masculinist tradition that posits La Gioconda as the transcendental signifier of female mystery. It becomes merely one signifier in a chain of referents that includes, as Trepka tells us, not only “the face [that] is the same as in the other portraits” (62) but also Bianca Capello, Lucrezia Borgia, Faustina, and Cleopatra, among others. And, as I will show, ekphrasis in Lee’s Amour Dure is characterized by a representational friction that results in parodic commentary upon Walter Pater’s writing on La Gioconda, as well as Leonardo’s original painting and the collective cultural “memories” of the sitter who inspired it.

In Amour Dure, Lee takes what is perhaps the most powerful example of the institutionalized silencing of woman under the male gaze and parodies centuries of male spectatorship and ekphrastic tradition that assert mastery over the female image. The folly of male academic tradition is made clear from the novella’s second paragraph, as Lee, through the voice of Trepka, refers to studies in art history as “falsehood” and “modern scientific vandalism.” Jaded and bored, Trepka self-deprecatingly confesses to his diary that he has been “given a traveling scholarship because I have written a book like all those other atrocious books of erudition and art-criticism,” and that his job is “to produce in a certain number of months … just another such book” (Lee 41-42). He berates himself, “Does thou imagine, thou miserable Spiridion, thou Pole growing into the semblance of a German pedant, doctor of philosophy, … dost thou imagine that thou, with thy ministerial letter and proof-sheets in thy black professorial coat-pocket, canst ever come in spirit into the presence of the Past?” (Lee 42).

This of course, is exactly what Trepka wants, but with a twist. He becomes so engrossed in his own egotistical desires that his interest in Urbania’s genius loci becomes transformed into a compulsion to possess the love of Urbania’s local ghost. Lee employs the diary entries recounting these events for a revelatory narrative effect. As Trepka learns more and more about Medea, he repeats the stories he knows and the reader sees them become more complex; thus Lee mirrors the process of acquiring knowledge, creating a widening series of concentric circles of information that get more detailed as time goes on. However, these repetitions also betray Trepka’s obsession and the way he embellishes the stories with his own revisionary fantasies of Medea. We see him—we catch him—in the process of imagining who she “really” is, so he can then claim that only he really understands her. Lee makes clear at this point, through the resonance of Bronzino’s painting with Leonardo’s, that this kind of masculinist intellectual history collapses Medea, countless other females, and ultimately La Gioconda, into one extravagant male fantasy of femininity, and thereby erases the lives of real women.

The speciousness of Trepka’s historical “method” is particularly apparent in an episode that pointedly creates representational friction between verbal and visual—between his description of the portrait of Medea and Bronzino’s actual portrait—with a change in a small but important detail regarding an object that might otherwise be overlooked. In Trepka’s description of Medea in the poppy-coloured dress, he says: “One hand holds a dull red rose” (Lee 62). In Bronzino’s portrait, the female figure instead holds a book. Let us examine more closely the implications of the representational friction between these two objects: the rose vs. the book.

When Trepka “meets” Medea in the church, she leaves him the rose that he reports in his version of the portrait—a rose that is all the more beautiful and rare because it is winter in Urbania. But within a few hours, the rose uncannily crumbles into ash and dust. The simple interpretation (and the one Trepka offers) is that the lovely rose falls apart because it, like the similarly captivating Medea, is three hundred years old. He doesn’t seem to care; instead of realizing he should beware the aura of sensual death that surrounds his object of desire, he melodramatically tells his diary that he would happily crumble to dust himself for the love of Medea. When we consider, however, that the rare rose (as opposed to the more intellectual book) is not “from” Bronzino’s painting but purely Trepka’s fantasy, then we realize (if we haven’t before) that Lee is building a case against him—she wants us to conclude that he is an unreliable narrator. When we further consider that the role of Bronzino’s painting in the first place is to create linkages between various women who, through portraiture, ekphrasis, or other “historical” means, have been transformed beyond recognition, then we realize Lee is creating an analogy between one unreliable narrator and a whole historical tradition. Trepka’s rose falls apart, and we suspect that many other representations of women would too.[13]

In his musings about La Gioconda, Pater romanticizes and demonizes the woman behind the famous painting, claiming the painting indeed, is a portrait, yet acknowledging that artistic impressions must always be somewhat subjective: “What was the relationship of a living Florentine to this creature of his thought? By what strange affinity had the dream and the person grown up thus apart, and yet so closely together?” (117). The male academic tradition that Amour Dure’s historian initially scorns (only soon to engage in himself) is precisely the tradition that Pater’s essay participates in, as he reinforces a reading of La Gioconda as femme fatale.[14] Famously, Pater writes:

We all know the face and hands of the figure … the unfathomable smile, always with a touch of something sinister in it … Hers is the head upon which all “the ends of the world are come,” and the eyelids are a little weary. … All the thoughts and experience of the world have etched and moulded there … the animalism of

Greece, the lust of Rome, the mysticism of the middle age with its spiritual ambition and imaginative loves, the return of the Pagan world, the sins of the Borgias. She is older than the rocks among which she sits; like the vampire, she has been dead many times, and learned the secrets of the grave. (116-118)

Through Trepka’s obsessive descriptions of Medea da Carpi, and especially with a similarly repetitive focus on face and eyes and hands, Lee echoes Pater, but with an irony that is hard to miss. Sounding like a caricature of Pater’s impressions of La Gioconda, Medea’s portrait is described:

The face is a perfect oval, the forehead somewhat over-round … Tight eyelids and tight lips give a strange refinement, and, at the same time, an air of mystery, a somewhat sinister seductiveness; they seem to take, but not to give. The mouth … looks as if it could bite or suck like a leech. … A curious, at first rather conventional looking beauty, voluptuous yet cold, which the more it is contemplated, the more it troubles and haunts the mind. … I often … [wonder] what this face, which led so many men to their death, may have been like when it spoke or smiled. (Lee 52)

Ultimately, instead of erasing the woman behind the portrait through these repetitive descriptions and fantasy projections of female beauty, Lee’s Medea, as Zorn has persuasively argued, disrupts others’ interpretations of her, and tells her own story. She traverses space and time, not merely within the psyche, as Pater suggests when he invokes “the animalism of Greece, the lust of Rome, the mysticism of the middle age … the return of the Pagan world, the sins of the Borgias” (Pater 118) but in “reality”: leaving letters, trysting in churches, and killing Trepka, yet another obsessed and possessive lover three hundred years after her own death. In this tale, the egocentric motivation of Trepka’s “love” appears ridiculous; but the quality of his interest in her is also conflated with the entire tradition of (male) art history on the one hand, and on the other, with each of her five husbands, who all treat her as chattel. All three kinds of male interest and “love” are thus condemned as acts of encroachment and violence, as Lee creates a female ghost who defends herself and retaliates.

Not content with being someone else’s mysterious daydream, universal or otherwise, Medea takes control. In so doing, Lee’s ekphrastic portrayal of the enigmatic portrait highlights the erasure of Leonardo’s model by parodying and hyperbolizing Pater’s already hyperbolic descriptions of “the presence that rose thus so strangely beside the waters” (Pater 118). “If history wishes to forever contemplate La Gioconda as mysterious and dangerous seductress,” Lee seems to say, “I’ll show you, what seductive feminine evil really is like!” Thus, this novella counters the erasure of La Gioconda by creating a Mona Lisa who literally cannot be contained. Yet Lee invites the careful reader, one perhaps already critical of easy fantasies of femme fatales with roses instead of real women with books, to ponder the implications of the novella’s representational friction. In Medea da Carpi, Lee creates an ekphrastic parody that exceeds any male spectator’s most fantastic nightmares, while imagining for the female spectator a vision of great female power, self-determination, and revenge.

II. Tawdry Trinkets: Graham R. Tomson (1889)

The second fin-de-siècle text I examine, “A Silhouette” from The Bird Bride (1889), was penned by a New Woman and female Aesthete who published verse under three pseudonyms: R. Armytage, Graham R. Tomson, and Rosamund Marriott Watson.[15] Under the first two names she contributed poems to leading periodicals and The Yellow Book, published book-length poetry collections of her own, and held well-attended literary “at homes” where she charmed a circle that included Oscar Wilde, Thomas Hardy, Mona Caird, Amy Levy, and Alice Meynell. Later, after a divorce, she adopted the name Rosamund Marriot Watson, and in addition to continuing to publish verse collections, became a reviewer for the Athanaeum, wrote a fashion column for The Scots Observer, and contributed to a prestigious interior design column for The Pall Mall Gazette.

Watson’s articles on interior design, later reprinted as The Art of the House, situate her among other women writing against what Talia Schaffer has identified as Aestheticism’s “masculinist intellectual tradition” (87). Indeed, as Schaffer observes, Watson used “interior design’s professionalization to enhance the status of quotidian feminine objects” while she simultaneously railed against amateur decorators who indulge in too many female ornaments (88). For instance, Watson’s writing on design frequently cautions that disorderly indulgence in poor taste and feminine frippery must be avoided; in true Aesthetic fashion, she describes how to discern between the charming and the vulgar. Such writing, for Schaffer, makes Watson an aesthetic radical who asserted that “housewifery is the origin of the aesthetic movement’s decorative renaissance” (Schaffer 91). Interestingly, in The Art of the House Watson also lectures, “[t]he arrangement of furniture is just as difficult and dangerous an art as landscape gardening or sonnet-making” (qtd. in Schaffer 88). In her comparisons of juggling words and arranging furniture, Watson implies that despite her own amateur status as a decorator, her experience as an author legitimates her taste. These arguments about interior design, with their unique juxtaposition of verbal and visual made in the context of everyday objects from the female sphere, provide a provocative backdrop for a discussion of ekphrasis in one of her earlier poems.

Published under the earlier name, Graham R. Tomson, “A Silhouette” from The Bird Bride provides an example of what might be called feminist ekphrasis on several accounts. First, in describing a cameo, “A Silhouette” challenges how gender inflects what might be the appropriate topic of ekphrastic writing. The poem begins:

There hangs her graceful silhouette

(A cameo, as it were, of jet),

Mine own familiar friend, and yet

By chance I found her

Half hidden in a dusty tray,

‘Mid tawdry trinkets of to-day,

While draggled stores of cast array

Hung all around her.Touched here and there with tarnished gold

Shines the small head, with tresses rolled

High in a knot of classic mould: (ll. 1-11)

As Schaffer notes, female Aesthetes sometimes took as subjects of artistic representation objects viewed “merely” as craft or as domestic art—functional rather than exclusively representational things. A piece of cameo jewelry resides on the spectrum between high art (like the Renaissance paintings appropriated by Lee in this essay’s previous section and Michael Field in the next) and objects like plates or mirrors—things Tomson addresses ekphrastically in other poems. The status of this cameo as art is further compromised because the speaker says, despite its grace, it is tarnished and “half hidden” in the dust. The alliterative emphasis on the objects that were its neighbors, the “tawdry trinkets of today” suggest that other spectators might view the cameo as no more beautiful than other detritus that have been similarly cast off, like the draggled clothing. A cynical reader might even suspect the speaker of being biased in singing the praises of her “familiar friend.”

Second, Tomson’s poem is interesting, especially from a feminist perspective, because it refuses to perform ekphrastic prosopopoeia, or “dramatic … envoicing of a mute, inanimate object” (Heffernan 22). In other words, Tomson’s speaker refuses to put words in the ekphrastic subject’s mouth. Instead, unlike Spiridion Trepka’s assertions about Medea (which create a different kind of female erasure), “A Silhouette” explicitly states that important information about the model’s personality, thoughts, and life are forever lost:

But whether writ in gold or tears

Or filled with homely hopes and fears,

Her story, with the withered years,

Is past and perished. (ll. 21-4)

These lines suggest death and burial, and in context of the first stanza, perhaps burial alive. We should know, or at least want to know, what the woman depicted by the cameo was like, but we are permitted neither answers nor speculation, not even the satisfaction of knowing if the silhouette depicts a friend or relative or the speaker herself. Linda K. Hughes seems to tend toward the former interpretation (106), while Ana Parejo Vadillo asserts it is the latter: the speaker “entering into a dialogue with her own past likeness” (141). For Vadillo, “A Silhouette”’s speaker is pondering how art tends toward fixing the “timeless beauty” of woman (139), and is critiquing, perhaps refusing, the presumably male artist’s rendition of her former self. Either way, Tomson refuses to speak for the inanimate art object or its model, even as the long-gone woman cannot speak for herself, illustrating one approach to what Elizabeth Loizeaux calls, in feminist ekphrasis, “self-conscious conversation with the idea of a mastering male gaze and a feminized art object” (81). Instead, the woman must remain mute (and abandoned), like her piano:

No longer jingles her spinet

To madrigal or minuet

But, dumb with mildew and regret,

And all asthmatic,

Forgetful now of tune and tone,

With hoary cobwebs overgrown,

And (save for nesting mice) alone,

Stands in an attic. (ll. 49-56)

The poem does personify the cameo: “By chance I found her” (l. 4) at the poem’s beginning and “We see her at her best” (l. 61) at its end; but of the real woman who inspired the art object, the speaker says only, “I see her in the distance dim” (l. 33). As Hughes remarks, “She reminds readers of the countless women whose stories have been lost” (106).

Throughout “A Silhouette,” representational friction between word and image is notable; and while the poem provides detail about what the cameo (not its model) looks like, the poem’s verbal representation serves mostly to reinforce the female speaker’s presence and gaze. We get a good sense of the spectator’s personality as she poses questions about the model:

Who watched her in the square oak pew?

Who praised her cakes and elder-brew?

Who sent her valentines—and who

Decried her beauty? (ll. 37-40)

Clearly this speaker understands that much of a woman’s social value is predicated upon her ability to perform domestic tasks, what others think of her appearance, and whether she is an object of desire. The reader also gains insight about the female spectator through her fantasies and questions about the dead woman, in the possibility of reading these questions and fantasies ironically (as a criticism of fin-de-siècle femininity), and most importantly, in her refusal to provide concrete answers.

In this way, “A Silhouette” provides a characteristic example of how Tomson “identifies the female body with transient, elusive grace that derives poignancy from the very fleetingness of its beauty” (Hughes 104). Yet, here Tomson also importantly affirms the presence of the female spectator and the power of the female subject to make decisions regarding the use of language and the violence of speaking for an (O)ther. Perhaps one could consider the poem’s stubborn assertions and refusals merely as one more example of traditional ekphrastic mastery of language over the visual; but I think it significant that the speaker’s language is marked by the insufficiency of both verbal and visual representation to communicate woman’s experience. The tone of the poem is ambivalent about the limits of both language and art as repositories of knowledge, since it is wistful, rather than accusatory. Indeed, the speaker, seeming to anticipate Jacques Derrida in The Truth in Painting, rather pragmatically accepts that any number of multiple possibilities might be true about the art object’s model, stating, “(Yet all surmise at most can be / But theoretic)” (ll. 15-16). Ultimately, thinking about ekphrasis in Tomson’s “A Silhouette,” as in Lee’s Amour Dure, reveals an instance of representational friction that exposes and criticizes female erasure. Both examples of representational friction also make use of gendered assumptions associated with an object; yet, each text goes about its feminist project quite differently. Contrary to Lee’s larger-than-life Medea/La Gioconda, Tomson’s poem represents just a shadow of the original woman. Nevertheless, the speaker admires and loves her, and asserts both their presences, even if one can only be a silhouette.

III: Spikes, Wheels, and Walls: Michael Field (1892)

Finally, let us turn to “Saint Katharine of Alexandria,” a sonnet written by Katharine Harris Bradley and Edith Emma Cooper under the collaborative pseudonym Michael Field. “Saint Katharine of Alexandria” was published in Sight and Song (1892), an ekphrastic verse collection inspired by Bradley and Cooper’s gallery tours on the Continent and art lessons with their friend, the art critic Bernard Berenson. As I have previously argued, Sight and Song provides queered and feminist perspectives for looking at female figures in art and culture, while the poems representing male figures are also coded to perform a critique of Victorian sex/gender ideology.[16] Although a fair amount of critical attention has been given to this fascinating collection, “St. Katharine of Alexandria” has remained under-examined.[17]

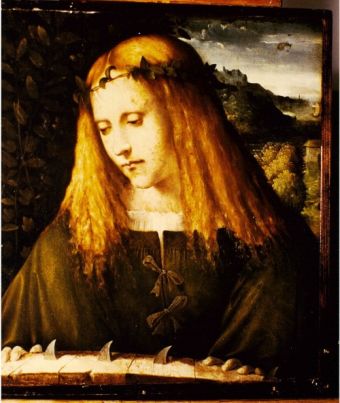

Any study of Michael Field’s “St. Katharine of Alexandria” that seeks to analyze the sonnet vis-à-vis its ekphrastic referent is difficult for readers today because Sight and Song confusingly informs the reader that the painting is by “Bartolommeo Veneto” [sic] and was viewed at “![]() Stadel’sche Institut at Frankfurt” [sic] (SS 31). Granted, Bartolomeo Veneto did paint a Saint Catharine of Alexandria, which is currently housed in

Stadel’sche Institut at Frankfurt” [sic] (SS 31). Granted, Bartolomeo Veneto did paint a Saint Catharine of Alexandria, which is currently housed in ![]() Glasgow (see Figure 2), but this is not the painting that is responsible for Michael Field’s poem in Sight and Song.

Glasgow (see Figure 2), but this is not the painting that is responsible for Michael Field’s poem in Sight and Song.

Figure 2. St. Catherine of Alexandria (c. 1520) Bartolomeo Veneto,

Kelvingrove Art Gallery and Museum, Glasgow

In contrast to Michael Field’s poem, this Catherine is crowned with jasmine, not bay; her hair is brown, not “yellow,” her fingers are not touching the wheel, and the landscape elements described in the poem are absent. While Sight and Song’s verse renditions of the Grand Masters’ works sometimes zero in on a minor figure or background element of its ekphrastic referent, and while their interpretations of the paintings are often quite creative and subjective despite their claims to objectivity, is it not characteristic of Michael Field to alter visual facts about the art objects they render into verse. If this is not the Frankfurt source of their “St Katharine of Alexandria,” what is?

The painting Bradley and Cooper viewed in Frankfurt in 1891 had been purchased by the museum in 1840 as a “Saint Catherine of Alexandria” by Cesare da Sesto (see Figure 3). The attribution changed to “Lombard Master” a few decades later. Then, around 1890, a small group of art critics, with Bradley and Cooper’s friend Bernard Berenson prominently at the fore, advocated that the work was actually painted by Bartolomeo Veneto, which explains Michael Field’s attribution as such in Sight and Song. Until now, the painting has not been identified by scholars seeking referents for Sight and Song’s picture-poems; indeed, the painting no longer exists as it was when Bradley and Cooper viewed it. Notably, what the co-authors originally saw as Saint Catherine’s wheel in 1891 was determined by the museum during a 1990 cleaning to be a wall with spikes added in the early nineteenth century—long after the painting’s original composition. The spikes were therefore removed by the restoration staff; and today the painting remains in Frankfurt’s Städelsches Kunstinstitut as Altobello Meloni’s “Narcissus at the Fountain.”[18] (see Figure 4).

With the poem’s referent no longer a mystery, we can now consider how representational friction functions, and indeed, is the primary ekphrastic technique driving the subtle feminist critique in this sonnet. Michael Field’s “Saint Katharine of Alexandria,” written back at their home on 10 October 1891, reads:

A little wreath of bay about her head,

The Virgin-Martyr stands, touching her wheel

With finger-tips that from the spikes of steel

Shrink, though a thousand years she has been dead.

She bleeds each day as on the day she bled;

Her pure, gold cheeks are blanched, a cloudy seal

Is on her eyes; the mouth will never feel

Pity again; the yellow hairs are spread

Downward as damp with sweat; they touch the rim

Of the green bodice that to blackness throws

The thicket of bay-branches sharp and trim

Above her shoulder: open landscape glows

Soft and apart behind her to the right,

Where a swift shallop crosses the moonlight. (SS 31) (ll. 1-14)

One immediately noticeable feature of this picture-poem is its restraint with a frequent ekphrastic device: enargeia, or vivid, lively description. Although, like the rest of Sight and Song, “Saint Katharine of Alexandria” provides much detail about the painting it references, the tone is markedly detached, thereby emphasizing the divide between spectator and image, and the spectator and the virgin-martyr herself.[19] And although Italian sonnets often move from an objectively descriptive octave to a more subjectively interpretative or explanatory sestet, at first glance this one seems to do the reverse, subtly conjecturing about Saint Katharine’s fingers shrinking from the spikes and her feelings of suffering and pity early in the poem, before moving to what appears to be mere surface description of her dress and the surrounding landscape. This detachment (along with other features I’ll discuss shortly) produces an effect Julia Saville has provocatively identified as an “austerity of poetics in Sight and Song, Michael Field’s experiment in ascetic withholding, learned from Pater” (178). According to Saville, Bradley and Cooper attempted to place themselves at a remove from the “feminine affect or Victorian slush” traditionally associated with Victorian poetesses (179) and instead, into conversation with their male Aesthete contemporaries; the female co-authors did this in Sight and Song’s preface by claiming, like Pater, to balance their subjective and objective impressions of a work of art:

the aim of this little volume is, as far as may be, to translate into verse what the lines and colours of certain chosen pictures sing in themselves … When such effort has been made, honestly and with persistence, even then the inevitable force of individuality must still have play and a temperament mould the purified impression (Field, SS vi)

Granted, Saville asserts that “the Paterian ascesis discreetly signals the male viewer’s desire for male beauty within a context of heterodox Oxonian Hellenism” and Bradley and Cooper’s experiment with “self-effacement yields a dividend of multiply dissident erotic perspectives” (Saville 180-1). I agree with those points; in fact, I would take them a bit further, and suggest that Sight and Song’s preface is usefully read as a legitimizing pose—one that softens unabashedly subjective notions by strategically asserting the volume’s seeming similarities with the poetics of their male contemporaries. Thus, as the ensuing discussion will demonstrate, “Saint Katharine of Alexandria”’s lack of enargeia and sense of detachment is deceptive; in fact, the poem provides subtle iconographic and verbal conduits for the spectator to engage intensely with Saint Katharine and to consider the speakers’ equally intense and subjective reactions to painting.

In addition to its minimal enargeia, but producing a similarly double-edged result, Michael Field’s “Saint Katharine of Alexandria” refrains from prosopopoeia. As a result, in contrast to much ekphrastic writing, but like Graham R. Tomson’s “A Silhouette,” here Michael Field only reservedly imagines what the painting’s subject might feel or say. Rather than dramatic envoicing through direct speech or free indirect discourse, the speaker refuses to speak for Saint Katharine and thus minimizes further violence against the virgin-martyr. Instead, Michael Field’s provocative impressions unfold though symbols, sounds, and inferences that call attention to the representational friction “between signifying medium and subject signified” (Heffernan 136).

Despite the poem’s restricted enargeia and prosopopoeia, closer analysis reveals how Michael Field directs the reader to specific details and symbolic linkages within the poem, suggesting a passionate feminist re-reading of history and implying that traditional hagiography and iconography provides an incomplete representation of the woman known as Saint Katharine. For instance, as this short poem opens (“A little wreath of bay”) and again near its end (“A thicket of bay branches sharp and trim”) the speaker emphasizes Saint Katharine’s intellectual accomplishments by pointing out the painting’s bay leaves, symbolic of learning and appropriate for Alexandria’s virgin-martyr, patroness of philosophers. Michael Field’s diary entry about their gallery visit also highlights the bay thicket and wreath:

Frankfurt. St Katharine—Bartolommeo Veneto. A dense corner covered with bay. Gold hair that has grown straight in the sweat of suffering—a head full, imaginatively, of the martyr’s doom, into the mystery of wh[ich]: she is looking, as the angels look into the mystery of the Cross. One little wreath of bay about her head. Faint, as in softened moonlight the world she has forsaken long ago. The sensitive finger-tips avoid the spikes of the wheel.[20]

Here, in addition to twice mentioning the bay, the journal entry makes contradictory observations about connection between the saint and the world that ultimately appear in the finished poem as aesthetic paradox. The diary reports Saint Katharine’s imaginings of being a martyr, and explains the faintness of the painting’s upper right hand corner by stating she has long forsaken the world; yet, it curiously asserts that her fingers avoid the spikes, which seems to imply that her acceptance of martyrdom and renunciation of the world are not quite complete. Here, my reading of the poem alongside the diary leads me to an interpretation that differs from Cheryl Wilson’s recent treatment of it. Wilson writes of Sight and Song‘s many “Saint Sebastian”s, “Saint Jerome,” and “Saint Katharine”: “Across all of these poems, Field creates a fairly straightforward equation in which the body is subject to pain but the spirit enables transcendence of that pain. Through the degradation of the body, the spirit is triumphant” (183). It is beyond the scope of this project to discuss the male matryrs here, but with regard to Saint Katharine, I am arguing that in their diary, Michael Field opines that the female martyr’s engagement with pain is actually quite ambivalent and contradictory.

The finished poem preserves these contradictions, illustrating what Marion Thain and others describe as Michael Field’s penchant for aesthetic paradox as a dominant poetic mode. Here, these paradoxes create representational friction between the poem and the painting and also between Michael Field’s ekphrastic rendition and legends, prayers, and hymns that emphasize Saint Katharine’s erasure to her martyrdom. These features of the poem raise questions for the reader: for instance, why does the poem connect Saint Katharine with the world and specifically mention that she avoids the spikes when most hagiography celebrates a saint’s willing martyrdom and rejection of the world? Why does the poem create a temporal paradox (another Michaelian characteristic[21]) stating, “She bleeds, each day as on the day she bled” (l. 5), even alliteratively suggesting that she has bled so much her face has become “blanched” (l. 6), yet not extending the temporal paradox to her pity—that emotion so readily associated with both saints and Victorian femininity? Lines 7 and 8 read, “the mouth will never feel / Pity again”. If she is perpetually bleeding why is she not perpetually pitying?

Possible answers to these questions are suggested by close attention to how this sonnet’s form helps to deconstruct the deceptively objective tone of its final sestet. “Saint Katharine of Alexandria,” like many Michael Field verses, is a modified Italian sonnet; and here, the rhyme scheme creates dual possibilities for reading. On the one hand we encounter a two-part Italian sonnet that ostensibly moves from subjective conjecture in the octave to objective observation in the sestet with a seemingly unremarkable volta at the semi-colon in line 9. On the other hand, the poem also bears resemblance to a four-part English sonnet divided topically/pictorially as follows: lines 1-4, bay wreath and spiked wheel as symbols of her famed intelligence and marytrdom; lines 5-8, eternally bleeding vs. never again pitying; lines 9-12, hair, bodice, and bay thicket; lines 13-14, the landscape and boat in the painting’s upper right corner. Enjambment across what would be the octave/sestet divide and across the line 12/final couplet divide mimics the visual sweep from point to point across the painting. And here is where Field makes things interesting and invites a more empathetic and engaged reading.

In devotional painting, the spectator is supposed to engage in a contemplative journey as a result of the eye’s movement across the painting’s landscape. Here, seemingly objective descriptions become more profoundly freighted with emotion and meaning after enjambment, sound devices, and imagery suggestively link objects in the visual field. For instance, alliterative and visual patterns create associations across the poem: she bleeds causing her gold cheeks to blanch; the similarly golden hair leads across the sonnet’s volta to her green bodice and to the darker green bay. This latter movement is driven by alliteration as well: b’s and th’s, “that to blackness throws / the thicket of bay-branches sharp and trim” (ll. 10-11). At this point, the sharp bay branches may motivate the spectator to move circularly back to the start of the poem and create associations between learning and martyrdom—between pointy bay and spiked wheel—and/or the sharp bay thicket may even transform the bay wreath into a crown of thorns. In this movement, what had appeared to be mere objective description becomes ekphrastic descriptio, or vivid description that exposes or suggests consequences: in this case, that women of learning will encounter painful difficulties. Michael Field’s curious emphasis on Saint Katharine’s fingers shrinking from the steel spikes, in this reading, can be explained as her effort to resist such consequences. As with Lee’s switching of Medea’s book for a rose, here, Michael Field’s reading of an object—the wheel’s spikes—creates representational friction with feminist implications. Despite the surface appearance of Paterian, ascetic tempering of subjective impression, the co-authors’ message is clear. Meanwhile, to return to our journey through the visual field, the eye is led by contrast from the bay thicket to the glowing open landscape and “swift shallop [that] crosses the moonlight” (l. 14), or what the diary entry describes as “Faint, as in softened moonlight the world she has forsaken long ago.” The fact that the bay thicket is what leads us to the boat brings to mind how, even though learning resulted in the saint’s embattled engagement with the world, study has also provided her with an escape: heavenly moments on earth that have preceded the final destination “soft and apart” for which she is about to embark.

Finally to return to the question of why Saint Katharine cannot be perpetually pitying if she is perpetually bleeding, lines 6-8 (“a cloudy seal / Is on her eyes; the mouth will never feel / Pity again;”) bring to mind not only the cloudy seal of her eyes but the fact that the saint’s mouth is sealed as well, through death, because she dared to challenge the Emperor Maxentius. This might lead the spectator to consider the links between emotion, speech, and action and the difficulty of being a woman of intellect and opinion in a male-dominated world that prefers a more self-sacrificing femininity. The poem’s representational friction supports an alternative ekphrastic hagiography and seems to suggest that if the female subject is not permitted to speak or act, then her pity will have limited reach. As Michael Field themselves put it, “we have much to say that the world will not tolerate from a woman’s lips” (WD 6).

Coda: Ekphrastic intra-action. Michael Field’s materials in their time and ours (2017)

The above discussion of “Saint Katharine of Alexandria” is a first attempt to analyze that particular picture-poem vis-à-vis the painting that was its referent—as Michael Field saw it in 1891. I don’t quite want to stop there, though, given that this is not how we see the painting now. As exciting as it has been to finally identify the image that inspired this ekphrastic sonnet, and to begin to analyze the two alongside one another, I want to dwell—and play—a bit more in the afterlife of Michael Field’s engagement with Saint Katharine—the poem and the painting—especially the effect, in our time, of the painting’s curious recent history.

How fascinating this story is, and how fitting, given what we know (or what we think we know) about Michael Field’s own play with sex and gender. Consider: the transformation of a material object—the painting—hinges on the transformation of an object represented within the painting: the spiked wheel that becomes a wall. This, in turn, literally engenders a Tiresian shift of the painting’s central figure: the eponymous female saint becomes the male youth, Narcissus. I can’t help but think that “Michael” and “Henry” (Katharine and Edith’s respective nicknames) would have been intrigued by this turn of events and, were they alive today, perhaps they would even perceive the transformation as resonating with their own verse renditions of the gender-bending “Tiresias” and “Caenis Caeneus.”

In the afterlife of the referent for Michael Field’s “Saint Katharine of Alexandria,” the wheel becomes a wall and a saintly maiden becomes a beautiful youth. Here, gender does not adhere in the subject, there is no materially bounded body that determines or forecloses the materially bounded objects—a corset, a bonnet, a razor and shaving soap—within that body’s reach. No, the wheel becomes a wall and a saintly maiden becomes a beautiful youth. In New Materialist parlance, this is a causal enactment, an instance of human-nonhuman mobility. An intra-action. Here, the object occasions the gender, an example of what the feminist philosopher-physicist Karen Barad would term “performative metaphysics,” borrowing from, then going a step further than, Judith Butler’s ideas about the subjectivating force of gender. Barad writes: “the universe is agential intra-activity in its becoming. The primary ontological units are not ‘things’ but phenomena-dynamic topological refigurings/ entanglements/ relationalities/ (re)articulations” (135). And so, the wheel becomes a wall and a saintly maiden becomes a beautiful youth.

In a future study I would be interested in teasing this out at greater length—the ways that this painting and poem, and perhaps all or most ekphrases, provide a case study for Barad’s claim that “matter is not immutable or passive” (139). Barad’s performative metaphysics are particularly apropos to Michael Field, I think, whose poems are so intensely permeated with affect, who dwelt so intimately with both natural and aesthetic objects—Christian and pagan, whose work in verse often rematerialized history with a difference, and who frequently insisted they still lived with their dead. Perhaps it would be useful to rethink ekphrasis with attention to both our own New Materialism and the late-Victorian Einfühlung (which also fascinated Vernon Lee), and so to attend to the dynamics by which art object and viewer intra-act, entangling object, referent, viewer, text, reader, and again, object and referent, in ongoing refigurings of meaning and affect. But that is a task for another day.

So to conclude this section, in a completely ahistorical turn, I now return with much irony to Michael Field’s insistence that Saint Katharine’s fingers avoid the spikes. Of course, I know that Bradley and Cooper had no way of knowing that the spikes were painted in and really “did not exist”; they could not have known that the figure in the painting is “really” Narcissus—that the wheel would become a wall, and the saintly maiden a beautiful youth. But oh, the irony: “the sensitive finger-tips avoid the spikes” while at the same time, out of time, in the latter-day material particularities of the provenance of this painting, the spikes engender the figure. The poem asserts her “finger-tips … from the spikes of steel / Shrink” (ll. 3-4). Her fingers avoid the object that signifies martyrdom, female martyrdom in particular. And what is a female who refuses to accept the self-renunciatory things, material and discursive, that make her a woman? The female becomes, in Michael Field’s time and still in ours, not-woman, if perhaps not quite a man. She is selfish, self-absorbed. It appears that she becomes Narcissus.

IV. Conclusion

Foucault’s essay on Las Meninas states, “the relation of language to painting is an infinite relation” (9). In the cases of Vernon Lee, Graham R. Tomson, and Michael Field, we see how the ekphrastic prose and poetry of three female Aesthetes gesture toward a series of infinite erasures only to critique them. If what is not “seen” is the flesh and blood woman who is the model, and if what is not seen cannot be written about, then the ekphrastic writer has a problem, because the subject of her ekphrasis is a cipher—she does not exist. Further, if a flesh and blood woman (who perhaps is the onlooker most likely to notice the female model) is not acknowledged as a spectator, how can one take seriously her writing about what only she sees?

This essay has been concerned with one historically specific literary response to these problems, ekphrastic representational friction, as a method through which four late-Victorian women approached issues of female spectatorship and the perplexing and complex question: How does a woman look? Popular culture at the fin de siècle has left us with numerous, and often parodic examples of what a woman looks like—the New Woman with her books and bicycle; the strong-jawed High Art Maiden with her peacock feathers and flowing locks. But how does a woman look—how does the late-Victorian woman look at art, at other women, at the history of art criticism, at her surroundings and the objects therein? And how might this reflect how she looks at herself? Through ekphrastic representational friction, often made possible via the invocation of specific objects imbued with aesthetic and/or gendered valences, Vernon Lee, Graham R. Tomson, and Michael Field look, critique the erasure of woman, and subtly offer possibilities.

Indeed, ekphrastic representational friction is a literary device that seems to have distinct benefits for Victorian female writers who have professional investments in keeping their critiques subtle. It places the burden of interpretation upon the viewer; permitting the spectator to draw his or her own conclusion, but only if they are ready to do so. Representational friction may lead the savvy onlooker to determine that previous representations are not accurate, such as Lee’s parodic, signifying rose. It may, like Tomson’s verse about the cameo, affirm a female spectator’s presence along with her power to make decisions about language and speaking for others. Or, like St. Katharine’s spikes, as in each of these three cases, representational friction may provide an opportunity for the writer to refuse traditional interpretations and renditions as they have been, and to suggest an alternative from

what is—a new idea of what could be.

published August 2017

HOW TO CITE THIS BRANCH ENTRY (MLA format)

Ehnenn, Jill R. “On Art Objects and Women’s Words: Ekphrasis in Vernon Lee (1887), Graham R. Tomson (1889), and Michael Field (1892).” BRANCH: Britain, Representation and Nineteenth-Century History. Ed. Dino Franco Felluga. Extension of Romanticism and Victorianism on the Net. Web. [Here, add your last date of access to BRANCH].

WORKS CITED

Barad, Karen. “Posthumanist Performativity: Toward an Understanding of How Matter Comes to Matter.” Material Feminisms. Ed. Stacy Alaimo and Susan Hekman. Bloomington and Indianapolis: Indiana UP, 2009. 120-154.

Colby, Vineta. Vernon Lee: A Literary Biography. Charlottesville and London: U of Virginia P, 2003.

Derrida, Jacques. The Truth in Painting. Chicago: U of Chicago P, 1987.

Djikstra, Bram. Idols of Perversity: Fantasies of Feminine Evil in Fin-de-Siècle Culture. New York: Oxford UP, 1986.

Ehnenn, Jill. “Looking Strategically: Feminist and Queer Aesthetics in Michael Field’s Sight and Son.” Victorian Poetry 42.3 (2004): 213-59.

Field, Michael. Sight and Song. London: Elkin Matthew and John Lane, 1892.

—. Works and Days: Selections from the Journals of Michael Field. Ed. T. Sturge Moore. London: Murray, 1933.

Foucault, Michel. The Order of Things. An Archaeology of the Human Sciences. New York: Vintage, 1973.

Fraser, Hilary. Women Writing Art History in the Nineteenth Century: Looking Like a Woman. Cambridge: Cambridge UP, 2014.

Hedley, Jane, Nick Halpern, and Willard Spiegelman, eds. In the Frame: Women’s Ekphrastic Poetry from Marianne Moore to Susan Wheeler. Newark: U of Delaware P, 2009.

Heffernan, James. Museum of Words: The Poetics of Ekphrasis from Homer to Ashbery. Chicago: U of Chicago P, 1993.

Hughes, Linda K. “A Fin-de-Siecle Beauty and the Beast: Configuring the Body in Works by “Graham R. Tomson” (Rosamund Marriott Watson).” Tulsa Studies in Women’s Literature 14.1 (1995): 95-121.

Lee, Vernon. “Amour Dure.” Hauntings and Other Fantastic Tales (1890). Ed. Patricia Pulham and Catherine Maxwell. Peterborough: Broadview, 2006. 41-76.

Loizeaux, Elizabeth Bergmann. Twentieth-Century Poetry and the Visual Arts. Cambridge and New York: Cambridge UP, 2008.

Mitchell, W.J.T. Picture Theory. Chicago: U of Chicago P, 1994.

Mulvey, Laura. “Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema.” Screen 16.3 (1975): 6-18.

Pater, Walter. Studies in the History of the Renaissance. London: Macmillan & Co., 1873.

Pollock, Griselda. Vision and Difference: Femininity, Feminism, and Histories of Art. London and New York: Routledge, 1988.

Psomiades, Kathy Alexis. Beauty’s Body: Femininity and Representation in British Aestheticism. Stanford: Stanford UP, 1997.

Rossetti, Christina. “In an Artist’s Studio,” The Complete Poems. Ed. R.W. Crump. London and New York: Penguin Classics, 2001. 796.

Rossetti, Dante Gabriel. “To Frederick Leyland, 18 August 1875”. The Correspondence of Dante Gabriel Rossetti, edited by William E. Fredeman. Woodbridge: D.S. Brewer, 2010. 72.10.

Saville, Julia. “Michael Field’s Poetic Imaging.” The Fin-de-Siècle Poem: English Literary Culture and the 1890s. Ed. Joseph Bristow. Athens: Ohio UP, 2005. 178-206.

Schaffer, Talia. The Forgotten Female Aesthetes: Literary Culture in Late-Victorian England. Charlottesville and London: U of Virginia P, 2000.

Thain, Marion. ‘Michael Field’: Poetry, Aestheticism and the Fin de Siècle. Cambridge: Cambridge UP, 2007.

Tomson, Graham R. “A Silhouette.” The Bird-Bride: A Volume of Ballads and Sonnets. London: Longmans, Green & Co., 1889. 67-70.

Vadillo, Ana Parejo. Women Poets and Urban Aestheticism: Passengers of Modernity. Houndmills, Basingstoke, Hampshire; New York: Palgrave, 2005.

Wilson, Cheryl A. “Bodily Sensations in the Conversion Poetry of Michael Field.” Victorian Poetry 54.2 (2016): 179-197.

Zorn, Christa. “Aesthetic Intertextuality as Cultural Critique: Vernon Lee Rewrites History through Walter Pater’s ‘La Gioconda.’” The Victorian Newsletter 91 (1992): 4-10.

ENDNOTES

[1] Heffernan’s introduction to Museum of Words (1993) deftly reviews debates regarding the definition and scope of ekphrasis. I find his emphasis on ekphrasis as an art/a form of representation to be a useful delineation that convincingly prevents ekphrasis from exploding more generally into any and all considerations of literary description; for the purposes of this piece I also appreciate Heffernan’s emphasis on ekphrasis’s paragonal energy and historical engagement with gendered norms. I will permit further definition of formal elements of ekphrasis to unfold organically with this essay’s argument, largely by way of example. For further reading, foundational book-length studies of ekphrasis include Gotthold Ephraim Lessing, Laocoön: An Essay on the Limits of Painting and Poetry (Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins UP, 1984); W.J.T. Mitchell, Iconology: Image, Text, Ideology (Chicago: U Chicago P, 1986); Murray Krieger, Ekphrasis: The Illusion of the Natural Sign (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins UP, 1992); Mitchell, Picture Theory (Chicago: U of Chicago P, 1994); John Hollander, The Gazer’s Spirit: Poems Speaking to Silent Works of Art (Chicago: U of Chicago P, 1995); and most recently, Brian Glaver, The Wallflower Avante-garde: Modernism, Sexuality, and Queer Ekphrasis (New York: Oxford UP, 2016).

[2] Elizabeth Loizeaux’s work on twentieth-century poetry argues for a feminist ekphrasis that “recognizes that a woman’s place as viewer is established within, beside, or in the face of a male-dominated culture, but that the patterns of power and value implicit in a tradition of male artists and viewers can be exposed, used, resisted, and rewritten” (81). Similarly, Hedley, Halpern, and Spiegelman examine how women used ekphrasis to bring gender-related questions and issues into the conversation (2009). Hedley, Halpern, and Spiegelman and Loizeaux’s work represent the primary book-length studies in the field, although they exclusively focus on women’s ekphrastic writing from modernism onward. Book-length analyses of women’s ekphrastic writing from earlier eras remain to be written.

[3] See, among others, Grant Scott, “The Fragile Image: Felicia Hemans and Romantic Ekphrasis.” in Felicia Hemans. Eds. N. Sweet N. and J. Melnyk. (London: Palgrave Macmillan, 2001): 36-54); Brian Eliot, “’Nothing Beside Remains’: Empty Icons and Elegiac Ekphrasis in Felicia Hemans.” Studies in Romanticism 51.1 (Spring 2012): 25-40; and Amy Gates, “Fixing Memory: The Effigial Forms of Felicia Hemans and Jeremy Bentham.” Women’s Writing 24.1 (2014): 58-73.

[4] See, among others, Antonio Losano, The Woman Painter in Victorian Literature (Columbus: Ohio SUP, 2008); and Emma Miller, “’Just as if She Were Painted’: Interpreting Jane Eyre through Devotional Imagery.” Brontë Studies: The Journal of the Brontë Society, 37.3 (2012): 318-32.

[5] See, among others, Lawrence Starzyk, “Elizabeth Siddal and the ‘Soulless Self-Reflections of Man’s Skill’” Journal of Pre-Raphaelite Studies, 16 (2007): 9-25; and Jill Ehnenn, “’Strong Traivelling’: Re-Visions of Women’s Subjectivity and Female Labor in the Ballad-Work of Elizabeth Siddal” Victorian Poetry, 52.2 (Summer 2014): 251-276.

[6] See, among others, Ana Parejo Vadillo, “Sight and Song: Transparent Translations and a Manifesto for the Observer.” Victorian Poetry 38.1 (2000): 15-34; Jill Ehnenn, “Looking Strategically: Feminist and Queer Aesthetics in Michael Field’s Sight and Song.” Victorian Poetry 42.3 (2004): 213-59; Krista Lysack, “Aesthetic Consumption and the Cultural Production of Michael Field’s Sight and Song.” SEL: Studies in English Literature 49.4 (2005): 935-960; Julia Saville, “The Poetic Imaging of Michael Field.” The Fin de Siècle Poem. Ed. Joseph Bristow. (Athens: Ohio UP, 2005. 178-206); Hilary Fraser, “A Visual Field: Michael Field and the Gaze.” Victorian Literature and Culture 34.2 (2006): 553-571; and Linda K. Hughes, “Michael Field (Katharine Bradley and Edith Cooper): Sight and Song and Significant Form.” The Oxford Handbook of Victorian Poetry (online, 2013).

[7] See, for example, Kate Flint, The Victorian and the Visual Imagination. (Cambridge: Cambridge UP, 2000); and Chris Otter, The Victorian Eye: A Political History of Light and Vision in Britain, 1800-1910 (Chicago: U of Chicago P, 2008).

[8] Although he did not necessarily self-identify as a feminist, John Berger’s Ways of Seeing (1972) also influentially critiqued the male gaze in Western art and culture and is a relevant example of the kind of critical thought anticipated by the women writers examined in this essay.

[9] While it is beyond the scope of this project to significantly engage here with the growing body of work on “thingness” in Victorian novels, my thinking has certainly been influenced by Victorianists’ ideas on objects, including Asa Briggs’s “things as emissaries” in Victorian Things, (Chicago: U of Chicago P, 1988); John Plotz’s writing on novels about and as Portable Property (Princeton: Princeton UP, 2008); and Elaine Freedgood’s claims about the importance of the “metonymic labor” of reading things in the Victorian novel, The Ideas in Things: Fugitive Meaning in the Victorian Novel (Chicago: U of Chicago P, 2006).

[10] For foundational work on Lee, see Vineta Colby’s Vernon Lee: A Literary Biography (Charlottesville, U of Virginia P, 2003); Christa Zorn, Vernon Lee: Aesthetics, History and the Female Intellectual (Athens: Ohio UP, 2003); and Patricia Pulham and Catherine Maxwell’s collection, Vernon Lee: Decadence, Ethics, Aesthetics Vernon Lee: Decadence, Ethics, Aesthetics (Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, 2006).

[11] “Portrait of Lucrezia Panciatici.” Web Gallery of Art. http://www.wga.hu/html_m/b/bronzino/2/panciat2.html. Accessed 18 July, 2017.

[12] Also see Laurel Brake, “Vernon Lee and the Pater Circle,” in Pulham and Maxwell.

[13] The other notable different between the original Bronzino painting and the one described by Trepka is the lady’s other hand, which in the “real” painting rests on the arm of the chair. In contrast, Trepka says that Medea’s hand, “long, narrow, tapering, plays with a thick rope of silk and gold and jewels hanging from the waist.” It is possible that the thick rope is a phallic reference and another example of Trepka’s obsession for Medea; however, it is also possible that Lee intentionally or unintentionally got the idea from a long jeweled belt seen in another Bronzino painting, “Portrait of a Lady” (c. 1550, Galleria Sabauda, Turin). Web Gallery of Art. http://www.wga.hu/html_m/b/bronzino/2/portlady.html. Accessed 18 July 2017.

[14] It bears noting that although he is rightly targeted by Lee here, Pater himself also departed from and thereby challenged traditional art historical writing (and sex-gender norms) by inserting an alternative (queer) subject into his writing. Thanks to Christa Zorn for reminding me to temper my feminist critique of Pater with an observation about queerness in Pater’s writing.

[15] For an excellent biography of Rosamund Marriott Watson, see Linda K. Hughes, Graham R.: Rosamund Marriott Watson, Woman of Letters (Athens, OH: Ohio UP, 2005). In what follows, I will refer to Tomson’s/Watson’s texts by the name under which they were published.

[16] See Ehnenn, “Looking Strategically”.

[17] See note 3 above for a select list of existing scholarship on Sight and Song.

[18] Jochen Sander, Italienische Gemälde im Städel 1300–1500: Oberitalien, die Marken und Rom (Kataloge der Gemälde im Städelschen Kunstinstitut Frankfurt am Main, 7) (Mainz, 2004), pp. 172-186. Many thanks to Stefania Girometti at the Städelschen Kunstinstitut Frankfurt for helping me identify this portrait and pointing me toward the Sander catalogue.

[19] According to tradition, Saint Katharine was the learned daughter of the king of fourth-century Alexandria. Intent upon remaining virgin, she refused suitors and became Christian after a vision where Mary gave her to Christ in mystical marriage. After she asked the Roman Emperor Maxentius to stop persecuting Christians, he arranged for fifty philosophers and orators to convince her she was wrong but Katharine won the debate. The fifty men, who converted to Christianity because of her intellect and persuasion, were beheaded and she was imprisoned and tortured. When the Emperor’s queen and her soldiers attempted to change Katharine’s mind, they too were swayed by her convictions. Maxentius ordered the soldiers beheaded and Katharine tortured on the breaking wheel. Miraculously, upon her touch the wheel was destroyed; so instead she was beheaded. For more on the virgin-martyr of Alexandria, see John Capgrave, The Life of Saint Katherine of Alexandria. trans. Karen Winstead, (U Notre Dame P, 2011).

[20] Michael Field, The Journals of Michael Field (1891). Unpublished MSS, Add. 46779 (London: The British Library), Folio 118.

[21] See Kate Thomas, “What Time We Kiss: Michael Field’s Queer Temporalities” GLQ 13:2-3 (2007): 327- 351.