Abstract

Walter Crane (1845-1915) was one of the most important, versatile, and radical artists of the nineteenth century: a painter, decorator, designer, book illustrator, poet, author, teacher, art theorist, and socialist. As a synthesis of art, design, and politics, Crane’s career offers new insights into the tradition of painting, the status of the decorative arts, and the transgression of their boundaries at the end of the nineteenth century. His work provides an important, decorative alternative to a realist idiom for socialist art.

For his contemporaries, Walter Crane’s artistic practice embodied the ethos of Arts and Crafts eclecticism. As the painter Sir William Rothenstein recalled in 1931, “He was illustrator, painter, designer, craftsman, and sculptor by turn; he poured out designs for books, tapestries, stained glass, wall-papers, damask, and cotton fabrics . . . he could do anything he wanted, or anyone else wanted” (292). Crane lived and worked among the unity of the arts—so much so that his astonishingly diverse body of work challenged the artistic and political establishment of his time. Like his friend and contemporary William Morris, Crane’s artistic practice overturned the conventional hierarchy of “high” fine art and “low” decorative art. Aesthetic concerns led both artists to declare allegiance to socialism. Yet Crane was not merely a mere follower of Morris. Politically and artistically, his formulation of art’s place in socialist agitation is distinct from Morris’s own. Testing the boundaries between “fine” and “decorative” through painting is fundamental to Crane’s socialist politics. In this way, Crane transformed “art for art’s sake” into “art for all.”

Born in ![]() Liverpool in 1845, Crane studied oil and watercolour painting from an early age with his father Thomas Crane, a painter trained at

Liverpool in 1845, Crane studied oil and watercolour painting from an early age with his father Thomas Crane, a painter trained at ![]() Royal Academy schools. In recollections of his early years, Crane noted, “I was always drawing, and any reading or looking at prints or pictures led back to drawing again” (“Work” 22). His youthful skill as a draughtsman led to an apprenticeship with the engraver and Chartist William James Linton. Later in life, Crane would hail Linton as both a political and artistic mentor. As Crane remembered in an interview in 1891, “the Pre-Raphaelites were being talked about, and above all Mr. Ruskin was driving his theories home . . . in Linton’s shop these things were talked about” (“Mr. Walter Crane” 6). Throughout the 1860s, Crane advanced his artistic training while supporting himself and his family as a freelance illustrator.

Royal Academy schools. In recollections of his early years, Crane noted, “I was always drawing, and any reading or looking at prints or pictures led back to drawing again” (“Work” 22). His youthful skill as a draughtsman led to an apprenticeship with the engraver and Chartist William James Linton. Later in life, Crane would hail Linton as both a political and artistic mentor. As Crane remembered in an interview in 1891, “the Pre-Raphaelites were being talked about, and above all Mr. Ruskin was driving his theories home . . . in Linton’s shop these things were talked about” (“Mr. Walter Crane” 6). Throughout the 1860s, Crane advanced his artistic training while supporting himself and his family as a freelance illustrator.

Crane undertook these decorative commissions at the same time that he sought to advance his career as a painter. Although he exhibited works at the ![]() Dudley Gallery throughout the 1860s and early 1870s, he achieved his greatest success with the opening, in 1877, of the Grosvenor Gallery, where he exhibited a number of works drawn from mythological subjects between 1877 and 1887. From 1868 onwards, “art for art’s sake,” championed by Algernon Charles Swinburne and Walter Pater among others, was a declaration of art’s autonomy from any ameliorative social function, whether intellectual or moral.[1] Crane’s historicizing and utopian canvases such as Renaissance of Venus (Fig. 3) from 1877 draw upon a British tradition of history painting in subject matter, style, public ambition, and the deployment of allegory to convey a moral message. Yet they simultaneously engage with the “art for art’s sake” credo and the modes of decorative painting then evolving. Crane situated his painting within a network of craft practices to suggest that painting itself is a craft. Participating in intellectual debates about aesthetics and artistic media, Crane helped to organize other artists to address these issues, first in the Art Workers’ Guild (established in 1884) and then the Arts and Crafts Exhibition Society, founded in 1887.

Dudley Gallery throughout the 1860s and early 1870s, he achieved his greatest success with the opening, in 1877, of the Grosvenor Gallery, where he exhibited a number of works drawn from mythological subjects between 1877 and 1887. From 1868 onwards, “art for art’s sake,” championed by Algernon Charles Swinburne and Walter Pater among others, was a declaration of art’s autonomy from any ameliorative social function, whether intellectual or moral.[1] Crane’s historicizing and utopian canvases such as Renaissance of Venus (Fig. 3) from 1877 draw upon a British tradition of history painting in subject matter, style, public ambition, and the deployment of allegory to convey a moral message. Yet they simultaneously engage with the “art for art’s sake” credo and the modes of decorative painting then evolving. Crane situated his painting within a network of craft practices to suggest that painting itself is a craft. Participating in intellectual debates about aesthetics and artistic media, Crane helped to organize other artists to address these issues, first in the Art Workers’ Guild (established in 1884) and then the Arts and Crafts Exhibition Society, founded in 1887.

In the mid-Victorian era, “decorative” art could be, and often was, public art. The placement of paintings within public interiors had been a national preoccupation since the unveiling of a scheme for the new ![]() Palace of Westminster in the 1840s, and because of the enthusiasm for public art, there were plans for mural decoration in several public buildings.[2] At the Palace of Westminster, perhaps the best-known example, decoration continued throughout the second half of the nineteenth century. Public art was, inevitably, moral art: the notion that art should have a public moral imperative had long held sway in England, and it found full expression in the Discourses (1768–90) of Sir Joshua Reynolds, the annual lectures given to students at the Royal Academy and the founding manifesto of academic art in Britain. In seeking to fulfil art’s moral duty, artists looked to historical examples of public art, most importantly the fresco painting of the Italian Renaissance.

Palace of Westminster in the 1840s, and because of the enthusiasm for public art, there were plans for mural decoration in several public buildings.[2] At the Palace of Westminster, perhaps the best-known example, decoration continued throughout the second half of the nineteenth century. Public art was, inevitably, moral art: the notion that art should have a public moral imperative had long held sway in England, and it found full expression in the Discourses (1768–90) of Sir Joshua Reynolds, the annual lectures given to students at the Royal Academy and the founding manifesto of academic art in Britain. In seeking to fulfil art’s moral duty, artists looked to historical examples of public art, most importantly the fresco painting of the Italian Renaissance.

It was John Ruskin, expanding the role of the art critic to encompass social analysis and reformist pronouncement, who first looked to the past to offer a clear vision of decorative painting as public painting. In his third lecture on “Modern Manufacture and Design,” delivered in ![]() Bradford on March 1, 1859, he argued that “all the greatest art which the world has produced” (italics his) was, in fact, decorative: ; for example, “Raphael’s best doing is merely the wall-colouring of a suite of apartments in the

Bradford on March 1, 1859, he argued that “all the greatest art which the world has produced” (italics his) was, in fact, decorative: ; for example, “Raphael’s best doing is merely the wall-colouring of a suite of apartments in the ![]() Vatican, and his cartoons were made for tapestries” (320-21). While conceding that what precisely constitutes decorative art “remains confused and undecided,” he maintains that decorative art is not “degraded” or “separate” from other art (320-21). Rather, “its nature or essence is simply its being fitted for a definite place”; this condition was the “only essential distinction between Decorative and other art” (320-21). Therefore, all art “may be decorative” if the artist is attentive to its place, purpose, and material” (320-21).

Vatican, and his cartoons were made for tapestries” (320-21). While conceding that what precisely constitutes decorative art “remains confused and undecided,” he maintains that decorative art is not “degraded” or “separate” from other art (320-21). Rather, “its nature or essence is simply its being fitted for a definite place”; this condition was the “only essential distinction between Decorative and other art” (320-21). Therefore, all art “may be decorative” if the artist is attentive to its place, purpose, and material” (320-21).

Crane was sensitive to the delicate interplay of aesthetics and politics in Ruskin’s writings, first encountered during his apprenticeship to Linton. In sketchbooks from 1863, he juxtaposed his drawings with extracts from Ruskin, including passages copied from Ruskin’s 1859 lecture “Modern Manufacture and Design.”[3] Ruskin opposed decorative art to portable art, that is to say, easel painting, which he derided as “for the most part ignoble” (320). The key to a “first-rate” portable picture, then, resides in its ability to match the ambition of decorative art, a project taken up by Crane in his paintings. Ruskin ends his lecture with a demand that decorative art should also be democratic art: “The great lesson in history is, that all the fine arts hitherto . . . have only accelerated the ruin of the states they adorned” (342). Addressing his audience of Bradford manufacturers directly, Ruskin suggests that they embrace “the loftier and lovelier privilege of bringing the power and charm of art within the reach of the humble and poor” (342). Ruskin here implicitly claims the moral grandeur of history painting—especially the uplifting, public role of history painting as it was understood in the Victorian era—for decorative art.

Crane believed that “the art that is capable of illustrat[ing the epic spirit] is what is called decorative art” (“English Revival” 823); furthermore, he endows “decorative art” in general and “painting as a decorative art” in particular with the moral weight heretofore given to painting as a fine art. Crane signalled this transformation of the decorative in his 1881 essay, “On the Position and Aims of Decorative Art,” a manifesto for the artist that is worth exploring in some detail.[4] He begins by alluding to Ruskin’s 1859 lecture with his assertion that “the grandest Art has always a monumental character, and . . . the highest kind of decoration is architecture” (227). Like Ruskin, he acknowledges that all art may be decorative, since “every picture and statue declares its original decorative purpose and architectural origin by the frame which surrounds the one, and the plinth which supports the other” (227). Yet here the resemblance to Ruskin ends, as Crane reveals his interest in the evolutionary theories of Charles Darwin and philosopher Herbert Spencer. If, as Crane suggests, “all art is organic,” then its history “is written in the records of the unending struggle for existence throughout Nature” (227).

The relationship of design to nature had preoccupied designers of the preceding generation. For Owen Jones and those in Henry Cole’s circle, writing after the ![]() Great Exhibition, the decorative drew its power from its ability to abstract and formalize natural motifs.[5] Crane proposes an entirely different relationship between art and nature. Rather than look to the natural world for the forms of ornament, Crane discerns in nature—nature, that is, viewed through a Darwinian prism—the underlying processes that governed art as well as biological life. It is “by selection, by gradual development, by adaptation” that art is thus “subject with all living things, to recurring seasons of growth, perfection, decline, and renaissance” (“On the Position” 227). But whereas pictorial art “is checked by a more or less immediate reference to Nature,” decorative art is “quite remote from Nature, as regards imitation of her forms. . . . Decorative or monumental art, in its higher forms, is capable of expressing, by its command of figurative and emblematic resources, more than is possible to purely pictorial art” (227). His ideas informed by the theories of Spencer, Crane regards natural processes as both cyclical and progressive: “There is, in fact, nothing beyond its [decorative art’s] range, by reason of its being more suggestive than imitative; and in its direction it becomes again, as at its beginning, but in a higher sense, a language—a picture-writing” (227). Because “truly, the world, to the decorative artist, is all before him, there to choose,” the artist must “make his world” and, thus, his art, and “people it with his thoughts” (228). Crane borrows the idea of “picture-writing” from Spencer (Spencer 288). Across artistic media, Crane used allegory to represent contemporary concerns as he set forth on canvas his hope—figured as Venus in his paintings from 1877, for example, and later in his political cartoons—for a social order renewed by socialism.

Great Exhibition, the decorative drew its power from its ability to abstract and formalize natural motifs.[5] Crane proposes an entirely different relationship between art and nature. Rather than look to the natural world for the forms of ornament, Crane discerns in nature—nature, that is, viewed through a Darwinian prism—the underlying processes that governed art as well as biological life. It is “by selection, by gradual development, by adaptation” that art is thus “subject with all living things, to recurring seasons of growth, perfection, decline, and renaissance” (“On the Position” 227). But whereas pictorial art “is checked by a more or less immediate reference to Nature,” decorative art is “quite remote from Nature, as regards imitation of her forms. . . . Decorative or monumental art, in its higher forms, is capable of expressing, by its command of figurative and emblematic resources, more than is possible to purely pictorial art” (227). His ideas informed by the theories of Spencer, Crane regards natural processes as both cyclical and progressive: “There is, in fact, nothing beyond its [decorative art’s] range, by reason of its being more suggestive than imitative; and in its direction it becomes again, as at its beginning, but in a higher sense, a language—a picture-writing” (227). Because “truly, the world, to the decorative artist, is all before him, there to choose,” the artist must “make his world” and, thus, his art, and “people it with his thoughts” (228). Crane borrows the idea of “picture-writing” from Spencer (Spencer 288). Across artistic media, Crane used allegory to represent contemporary concerns as he set forth on canvas his hope—figured as Venus in his paintings from 1877, for example, and later in his political cartoons—for a social order renewed by socialism.

HOW TO CITE THIS BRANCH ENTRY (MLA format)

published August 2012

O’Neill, Morna. “On Walter Crane and the Aims of Decorative Art.” BRANCH: Britain, Representation and Nineteenth-Century History. Ed. Dino Franco Felluga. Extension of Romanticism and Victorianism on the Net. Web. [Here, add your last date of access to BRANCH].

WORKS CITED

Chesterton, G. K. A Miscellany of Men. New York: Dodd, Mead, 1912. Print.

Crane, Walter. “Of Aesthetic Pessimism and the New Hope.” Knight Errant 1.2 (1892): 40. Print.

—. “Art and Character.” Character and Life: A Symposium. Ed. Percy L. Parker. London: Williams and Norgate, 1912. 110-14. Print.

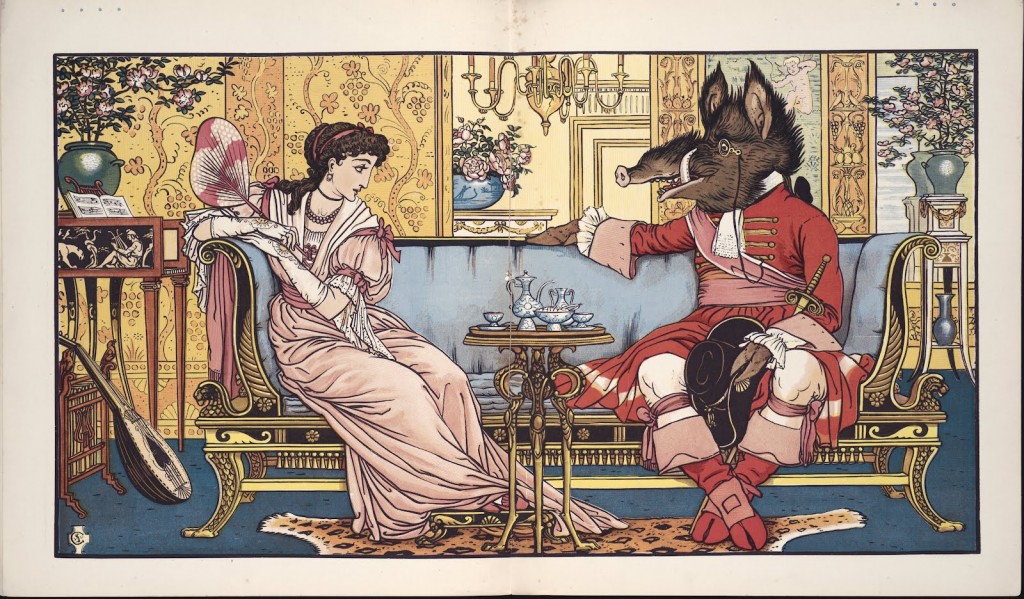

—. Beauty and the Beast. London: Routledge, 1875. Print.

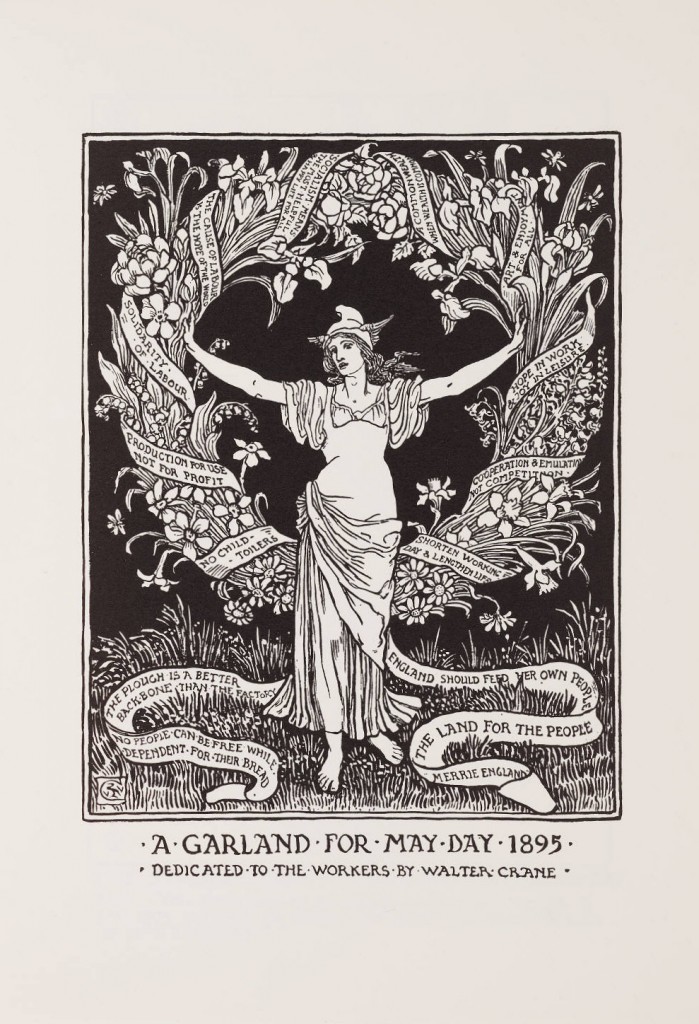

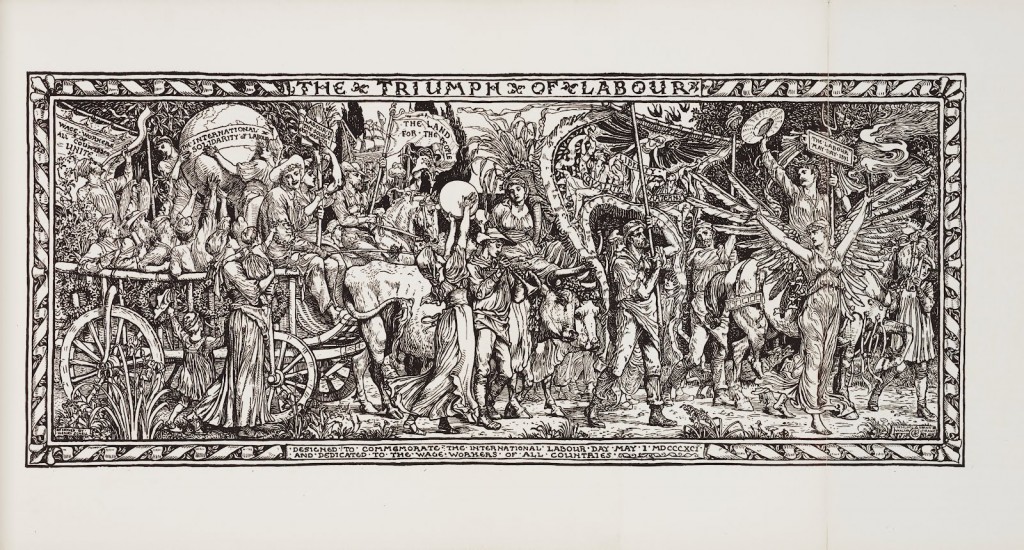

—. Cartoons for the Cause: A Souvenir of the International Socialist Workers and Trade Union Congress, 1886-1896. London: Twentieth Century, 1896. Print.

—. Claims of Decorative Art. London: Lawrence & Bullen, 1892. Print.

—. “The English Revival in Decorative Art.” Fortnightly Review 58 (July 1892): 815-25. Print.

—. “Notes on My Own Books for Children.” Imprint (1913): 81-86. Print.

—. “On the Position and Aims of Decorative Art.” Art Journal ns (1881): 227-8. Print. Rpt. as “The Claims of Decorative Art” in Crane, The Claims of Decorative Art 1-6.

—. Work of Walter Crane with Notes by the Artist. Spec. issue of Art Journal (Easter 1898). Print.

Hyndman, Henry Mayers. Further Reminiscences. London: Macmillan, 1912. Print.

“Mr. Walter Crane and His Picture-Books: An Interview at Beaumont Lodge.” Pall Mall Budget 25 June 1891: 6. Print.

O’Neill, Morna. “Art and Labour’s Cause is One”: Walter Crane and Manchester, 1880-1915. Manchester: Whitworth Art Gallery, 2008. Print.

Prettejohn, Elizabeth. Beauty and Art: 1750-2000. Oxford: Oxford UP, 2005. Print.

—. “Walter Pater and Aesthetic Painting.” After the Pre-Raphaelites: Art and Aestheticism in Victorian England. Ed. Elizabeth Prettejohn. Manchester: Manchester UP, 1999. 36-58. Print.

Rothenstein, William. Men and Memories. New York: Coward-McCann, 1931. Print.

Ruskin, John. The Two Paths. Ed. E. T. Cook and Alexander Wedderburn. London: Allen, 1903. Print. Vol. 16 of The Works of John Ruskin. 39 vols. 1903-12. Print.

Spencer, Herbert. First Principles. 1864. New York: Appleton, 1898. Print.

Willson, Clare A. P. Mural Painting in Britain 1840-1940: Image and Meaning. Oxford: Oxford UP: 2000. Print.

Wornum, Ralph. Analysis of Ornament: The Characteristics of Styles, etc. 1856. London: Chapman and Hall, 1882. Print.

FURTHER READING

Engen, Rodney. Walter Crane as Book Illustrator. London: Academy Editions, 1975. Print.

Gerard, David. Walter Crane and the Rhetoric in Art. London: Nine Elms, 1999. Print.

Konody, P.G. The Art of Walter Crane. London: Bell, 1902. Print.

Lundin, Anne H. Victorian Horizons: The Reception of the Picture Books of Walter Crane, Randolph Caldecott and Kate Greenaway. London: Scarecrow, 2001. Print.

O’Neill, Morna. Walter Crane: The Arts and Crafts, Painting, and Politics, 1875-1890. New Haven: Yale UP, 2010. Print.

Spencer, Isobel. Walter Crane. London: Studio Vista, 1975. Print.

RELATED BRANCH ARTICLES

ENDNOTES

[1] For an overview of this topic, see Prettejohn, Beauty and Art: 1750-2000 111-56.

[2] For further discussion, see Willsdon.

[3] Now in the Walter Crane Archive, Whitworth Art Gallery, University of Manchester.

[4] He would later re-title this essay “The Claims of Decorative Art” when he published his first volume of essays, also titled The Claims of Decorative Art, in 1892.

[5] See, for example, Wornum.