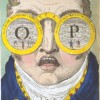

Rebecca Nesvet, “Miss Whitehead, ‘The Bank Nun’”

An urban legend maintains that early in the nineteenth century, one Miss Whitehead, colloquially known as “the Bank Nun,” frequently visited the Bank of England to accuse that institution of destroying her brother, a financial forger. This essay traces the evolution of this legend. I contend that in 1837, an obscure comic sketch reacted to that year’s major financial crisis by dredging up the Romantic-era case of financial forger Paul Whitehead and focusing on his surviving sister. Displacing her brother’s notoriety onto her, the sketch reinvents her as “the Bank Nun,” a grotesque magnet for lingering Romantic-era anxieties about the circulation of paper credit, financial forgery, and women. A succession of plagiarisms, retellings, and reappraisals of this ephemeral sketch and its portrait illustration made the Bank Nun a folk heroine of enduring resonance. Via this iconic figure, Romantic-era economic controversy haunts London today.

Joanne Wilkes, “The Implications of the Cricket Match in Anthony Trollope’s The Fixed Period (1882)”

Anthony Trollope’s late novel The Fixed Period (1882), set a century in the future in a fictional South Pacific island, has often puzzled readers. It deals with a policy of compulsory euthanasia in the politically independent island of Britannula, a policy that is overturned when the island is taken over by Britain. My article aims to explain an odd interlude in the novel: a cricket match in Britannula between a local and an English team. Drawing on the history of cricket matches between England and its antipodean colonies around the time of the novel’s composition, I argue that the cricketing interlude serves to highlight the text’s take on the Britannulans. This community, living a hundred years in the future, claims to be autonomous, but it possesses a mindset still governed by a sense of Britain as the “mother country.” Hence Trollope emphasizes how difficult it is for settler societies to shake off such attitudes and ties.

Janice Schroeder, “The Publishing History of Henry Mayhew’s London Labour and the London Poor”

Versions of Henry Mayhew’s massive social survey London Labour and the London Poor appeared in several publishing formats, including newspaper column, weekly serial, live stage show, and bound volume. This article traces the republication and remediation of London Labour alongside Mayhew’s repackaging of his interviews with London “street-folk” from 1849 onwards. I offer a succinct, accessible account of the complex publishing history of the text, from print newspaper column to digital edition.

Jonathan Mulrooney, “Edmund Kean, Event”

This article considers Regency actor Edmund Kean’s presence as a figure in the theatrical news of the day, arguing that Kean’s acting style, coupled with changes in periodical print culture, reframed the relation between the British theatrical tradition, the actor’s stage performance, and audience reception. Emphasizing an “illegitimate” grammar of representation characterized by gesture, mobility, and emotional transition, Kean enacted new forms of subjectivity that aligned with emerging modes of theatrical criticism to shape readers’ concepts of their own private experience and their imagined engagement with public events.

Terry F. Robinson, “National Theatre in Transition: The London Patent Theatre Fires of 1808-1809 and the Old Price Riots”

The years 1808-1809 mark a major period of transition in English National Theatre. In the space of just a few months, London’s two patent playhouses—the Theatres Royal Covent Garden and Drury Lane—burned to the ground. The devastation was total and complete. This article tells the story of the two theatre fires and explores their economic, political, and cultural repercussions, direct and indirect, including the reconstruction of Covent Garden and Drury Lane, the Old Price Riots, and the career dénouements of Richard Brinsley Sheridan, John Philip Kemble, Sarah Siddons, and Dorothy Jordan. In the process of providing a historical and graphic overview, it proposes that the London Theatre fires of 1808-1809 not only created significant professional and financial turmoil but also helped to engender a shift from an eighteenth-century to a nineteenth-century theatrical paradigm.

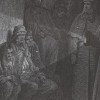

Heidi Kaufman, “1800-1900: Inside and Outside the Nineteenth-Century East End”

This essay examines depictions of one of the infamously well-known region of London called “The East End.” Scholarly and popular discussions of this part of the city have been dominated by texts emphasizing the East End’s seedy or sensational social and economic features. In particular, popular writing has focused on the history of poverty, crime, and resident “alien” or immigrant groups living in the East End. While such stereotypes were often loud in their sensationalism, and while they often overpowered competing narratives, this essay makes the case for reading them alongside a range of narratives about the East End, many of which were produced by residents of this part of London. In what follows, I consider a mix of insider and outsider lenses, of well-known and lesser-known voices that produced a varied range of depictions of the nineteenth-century East End. In the process, I argue that the East End ought not to be characterized as simply a site of crime and poverty. To understand this important part of London, we must instead examine a fuller range of voices emerging from disparate, often competing, perspectives. Through this mix, we can begin to register the East End’s economic, cultural and social diversity witnessed and described in discordant ways by visitors and residents alike.

Robert O’Kell, “On Young England”

Young England was a short-lived social and political movement that developed from the altruistic ideas of a small parliamentary ginger group within the Conservative Party in the 1840s. At the core of the movement were Benjamin Disraeli (their acknowledged leader), Lord John Manners, George Sydney Smythe and Alexander Baillie Cochrane, all of whom were appalled at the state of party politics, class conflict, and the economic and moral condition of Victorian England’s poor. Their dissatisfaction with Sir Robert Peel’s leadership of the Party gained popular momentum when, between 1844 and 1847, Disraeli published a trilogy of novels that embodied both devastating satirical attacks on traditional Tory politics and an idealistic, nostalgic vision of a revitalized aristocracy motivated by social duty.

Mark Schoenfield, “The Trial of James Stuart (1822): ‘Abuse of the Press, and Duelling'”

This essay explores the trial of James Stuart on the charge of murder, for fatally shooting Alexander Boswell (James Boswell’s son) in a duel. The dispute between Stuart and Boswell was part of the acrimonious paper war between Scottish Whig and Tory newspapers. Stuart’s acquittal as well as the mode of his defense, largely conducted by Henry Cockburn and Francis Jeffrey (both Whig lawyers and the latter the editor of the Edinburgh Review), demonstrate the mutual reliance and interconnections between the periodical press, the illegal practice of dueling, and the criminal court system.

Florence S. Boos, “The Education Act of 1870: Before and After”

Nineteenth-century England was relatively backward in providing its citizens with basic skills. Education was highly stratified by class, and pervasive child labor, sectarian religious competition, and reluctance to levy taxes for schools all delayed the systematic provision of elementary education for the children of the working-classes. The Education Act of 1870, which acknowledged and codified for the first time a Crown responsibility for elementary schools, was a watershed in the provision of universal instruction. Even this advance had been hotly contested, and it would be another twenty years before (almost) all British children benefited from a primary school education. Critics of the Education Act of 1870 and its successors noted that the system of inspections it mandated tended to encourage rote learning and limit the range of subjects taught, and those who favored secular public education, including workers’ organizations, resented continued government support for sectarian schools.

Florence S. Boos, “The Socialist League, founded 30 December 1884”

The Socialist League was one of several early socialist groups which arose in Great Britain during the 1880s. Among these, the League was distinctive for its eclectic membership and its focus on education and outreach as the most effective means to social change. Its notable members included William Morris, Tom Maguire, Andreas Scheu, Bruce Glasier, and for a time, Friedrich Engels, Eleanor Marx, and Edward Aveling. During its four years of greatest activity from 1885 through 1889, its vigorous program of lectures, open-air meetings, and publications, including Commonweal, reached a wide audience through campaigns on behalf of free speech, miners’ strikes, an international workers’ movement, and the reorganization of society “from the root up.” Its internationalism, strong support for the Second International, and consistent anti-imperialism gave its revolutionary ideals a broad, forward looking cast. Its focus on education, outreach, and alternative forms of social organization also attracted writers, artists and intellectuals who promoted its holistic ideals through creative works and contributed to its journal Commonweal. On the other hand, as an organization founded before the election of working-class representatives seemed feasible, its continued commitment to advocacy and “pure” socialism—as opposed to party politics—ultimately rendered it less viable than more pragmatically oriented groups such as the emerging Independent Labour Party.