Abstract

An urban legend maintains that early in the nineteenth century, one Miss Whitehead, colloquially known as “the Bank Nun,” frequently visited the Bank of England to accuse that institution of destroying her brother, a financial forger. This essay traces the evolution of this legend. I contend that in 1837, an obscure comic sketch reacted to that year’s major financial crisis by dredging up the Romantic-era case of financial forger Paul Whitehead and focusing on his surviving sister. Displacing her brother’s notoriety onto her, the sketch reinvents her as “the Bank Nun,” a grotesque magnet for lingering Romantic-era anxieties about the circulation of paper credit, financial forgery, and women. A succession of plagiarisms, retellings, and reappraisals of this ephemeral sketch and its portrait illustration made the Bank Nun a folk heroine of enduring resonance. Via this iconic figure, Romantic-era economic controversy haunts London today.

In January, 1940, in ![]() New York City, W.H. Auden completed his long poem New Year Letter, a work laced with free-associative brief homages to minor historical figures and popular heroes. In one such digression, the expatriate English poet looks back across the Atlantic and recalls a well-established London legend. He praises “SARAH WHITEHEAD, the Bank Nun,” who:

New York City, W.H. Auden completed his long poem New Year Letter, a work laced with free-associative brief homages to minor historical figures and popular heroes. In one such digression, the expatriate English poet looks back across the Atlantic and recalls a well-established London legend. He praises “SARAH WHITEHEAD, the Bank Nun,” who:

Pacing

Threadneedle Street in tears,

… watched one door for twenty years,

Expecting, what she dared not doubt,

Her hanged embezzler to walk out.

(Auden, Collected Poems 206)

By 1940, this “Miss Whitehead” was well known as the heroine of an urban legend. This myth maintained that early in the nineteenth century, a woman of that name regularly visited the ![]() Bank of England in London’s Threadneedle Street to search for her elder brother, a Bank clerk who had been hanged for forgery, or else to implicate the Bank in his downfall. In most versions of the story, Miss Whitehead dresses in black garments, earning the nickname “the Bank Nun.” Some Victorian authors insisted that she was a historical figure active in living memory. In 1880, the novelist and cartoonist Charles Henry Ross claimed that in his childhood he personally encountered her. Adults “pointed out” to him “a wild-looking elderly woman, dressed in shabby mourning,” who “rambled through the City streets, or hung round the Bank,” “muttered to herself in impotent rage,” and “shrilly accuse[d] the Bank authorities, on whose charity she mostly lived, of robbing her” (Ross 84). Sixty years after Ross published this anecdote, Auden’s New Year Letter testifies to the Bank Nun’s enduring cultural resonance.

Bank of England in London’s Threadneedle Street to search for her elder brother, a Bank clerk who had been hanged for forgery, or else to implicate the Bank in his downfall. In most versions of the story, Miss Whitehead dresses in black garments, earning the nickname “the Bank Nun.” Some Victorian authors insisted that she was a historical figure active in living memory. In 1880, the novelist and cartoonist Charles Henry Ross claimed that in his childhood he personally encountered her. Adults “pointed out” to him “a wild-looking elderly woman, dressed in shabby mourning,” who “rambled through the City streets, or hung round the Bank,” “muttered to herself in impotent rage,” and “shrilly accuse[d] the Bank authorities, on whose charity she mostly lived, of robbing her” (Ross 84). Sixty years after Ross published this anecdote, Auden’s New Year Letter testifies to the Bank Nun’s enduring cultural resonance.

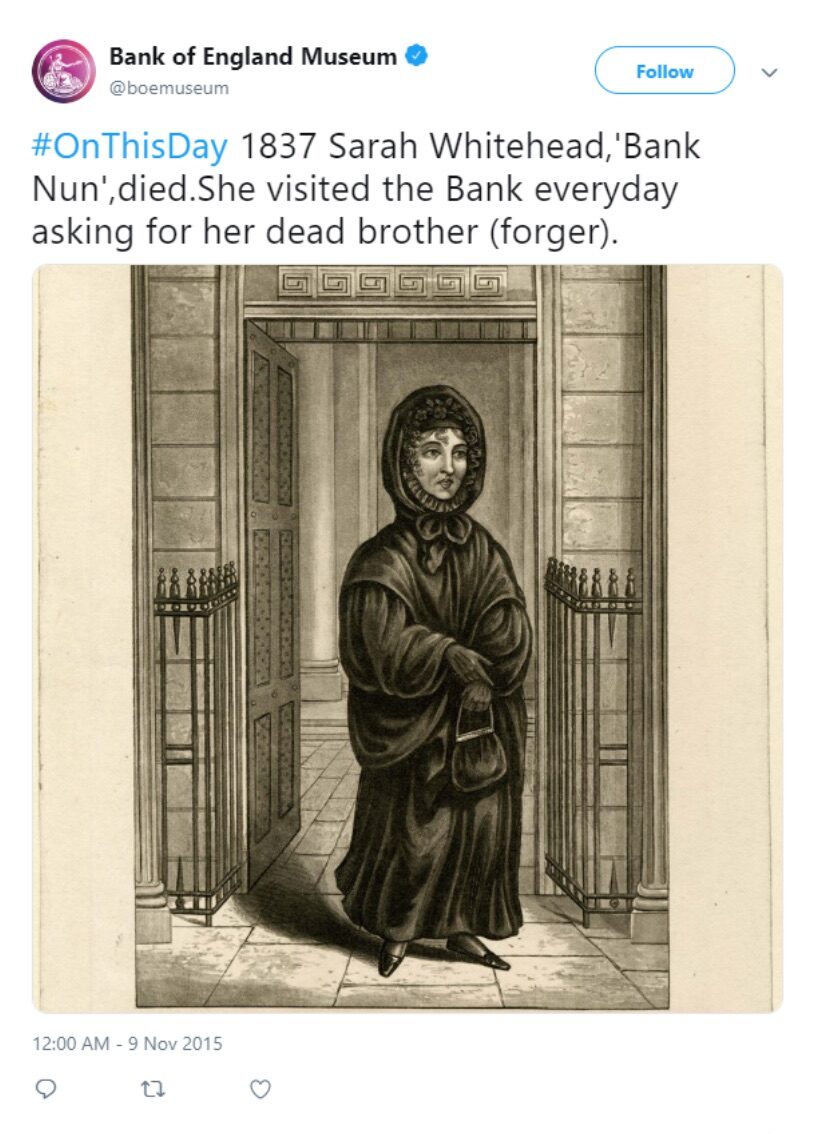

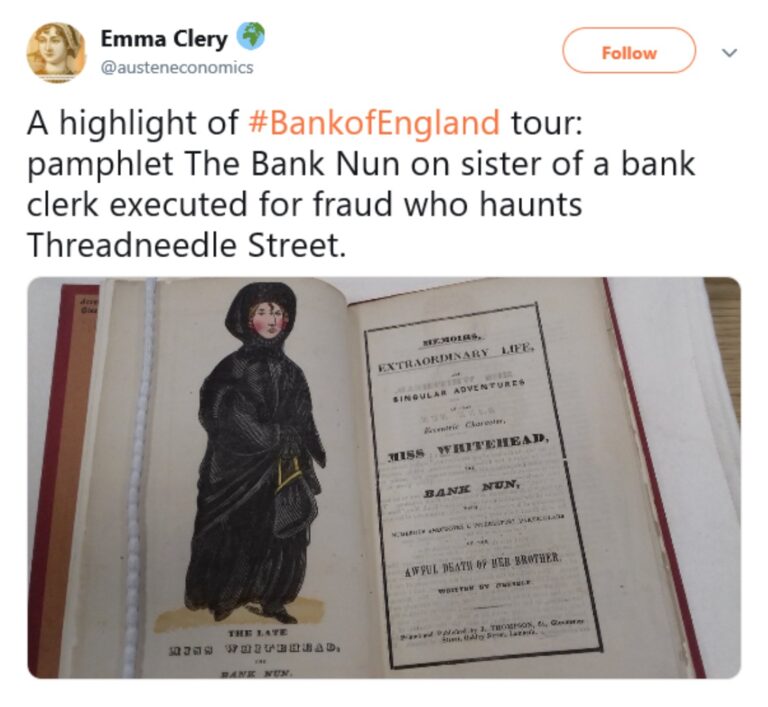

So does the London heritage industry of the twenty-first century. “#OnThisDay 1837 Sarah Whitehead, ‘Bank Nun’, died,” the Bank of England Museum tweeted on 9 November 2015. “She visited the Bank everyday [sic] asking for her dead brother (forger)” (Figure 1). According to another tweet, the tale of the Bank Nun is “a highlight” of the Museum’s tour. In this tweet, historian Emma Clery presents the Bank Nun as an apocryphal figure who has entered the realm of Bank of England mythology (Figure 2). The “sister of a bank clerk executed for fraud,” the Bank Nun “haunts Threadneedle Street” (Clery), refusing to let her brother’s memory die with him.

How and why did this bizarre legend arise? Scholars have established that it derives from the history of financial forger Paul Whitehead. Executed in 1812, Whitehead left an unmarried sister, but precisely when and why this woman evolved into the Bank Nun has yet to be documented. This essay traces that evolutionary process.[1] I contend that Paul Whitehead captivated Romantic-era observers as a perfect bogeyman of the financial forgery panic of the Restriction period (1797-1821). In 1837, an obscure comic sketch reacted to the major financial crisis of that year by dredging up Whitehead’s case but focusing on his surviving sister. Displacing Whitehead’s notoriety onto this sister, the sketch transformed her into “the Bank Nun,” a grotesque magnet for lingering Restriction-era anxieties about the circulation of paper currency, financial forgery, and women. A succession of plagiarisms, retellings, and reappraisals of the sketch and its portrait illustration made the Bank Nun a metropolitan folk heroine of enduring cultural resonance. Via this icon, Romantic-era economic controversy haunts London today.

Finance, Forgery, and Fear

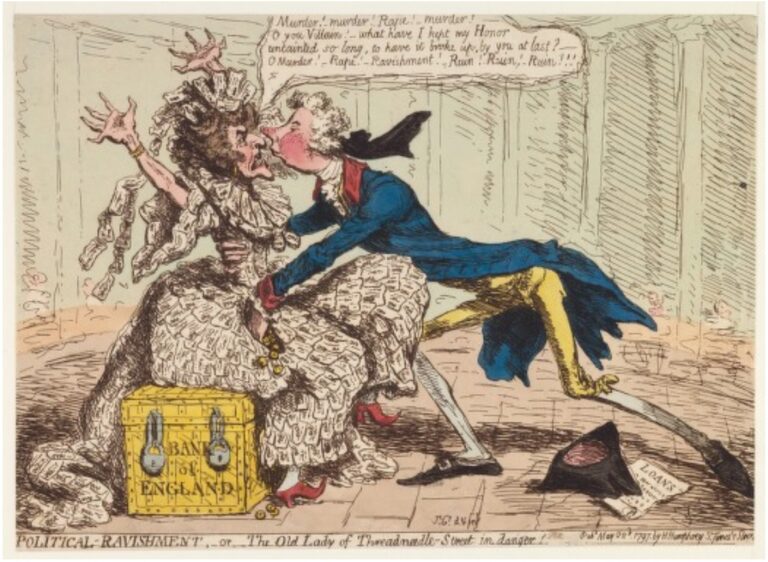

In 1812, fears of paper credit and financial forgery pervaded British cultural discourse. Eighteenth-century Britain had developed many new forms of credit, especially paper currency. In 1797, in response to the threat of French invasion, Parliament passed the Bank Restriction Act. This act clawed back bullion so that it could be sent to the Continent to pay for war. The bullion was replaced with paper currency, which could not be automatically exchanged for gold. Small banknotes proliferated and the new credit culture acquired prominent defenders, including economist David Ricardo and Prime Minister Spencer Perceval. However, gold was widely considered stable, dependable, and real (Alborn 35). Conversely, as Alexander Dick explains, paper currency seemed “ghostly, insidious, and fragile” (Dick, Romanticism and the Gold Standard 10). A famous cartoon by John Gillray, “Political Ravishment, or “The Old Lady of Threadneedle-street in Danger!” (1797) illustrates this paradigm. Gillray allegorizes the Bank of England as an “old maid” assaulted by the pro-currency Prime Minister Pitt (Figure 3). This symbolic rape robs the Old Lady of the bullion, or real value. Later, as the war with Napoleon wore on, the controversy deepened. In 1809-12, a pamphlet war debated the “bullion question,” that is, whether a bullion or paper-based financial system was best for Britain. The new paper currency had proven extremely susceptible to forgery, which increased dramatically during the Restriction period. In response, Parliament passed thirty-six new forgery statutes, most carrying the death penalty. Armed with these statutes, the Bank of England zealously pursued forgery prosecutions and executions. Many of the condemned were innocents who had uttered (attempted to cash or spend) banknotes that they did not know were counterfeit.

Figure 3. James Gillray. “Political Ravishment, or The Old Lady of Threadneedle-street in Danger!” 1797.

The bullion question and forgery panic fundamentally shape Romantic thought and writing. The bullion controversy reached its apogee in May 1812, when a bullionist agitator of unsound mind assassinated Perceval, but Romanticism’s heyday eerily overlaps with Restriction. That economic policy began in 1797, the year before the publication of William Wordsworth and Samuel Taylor Coleridge’s Lyrical Ballads, continued through 1816, when Britain officially established a gold standard for the first time in its history, setting the rate at which paper stood in for still elusive gold, and ended in 1821, the year of John Keats’s death, with the resumption of cash payments (Dick, Romanticism 9). Moreover, some of the more prominent texts of the bullion controversy sound Romantic. One example is the radical journalist William Cobbett’s polemic “Paper Against Gold” (1817). In this work, Cobbett argues that “all state credit is … fraudulent” (Dick, Romanticism 83) and proposes that some talented engraver should flood London with forged banknotes. This vigilante act would compel the discontinuation of real notes and consequently equip working-class people with the economic power that the credit economy denies them (Benchimol, par. 17). This utopian redistribution of economic power seems positively Promethean.

Romantic imaginative writing, too, engaged deeply with the bullion controversy. While some of the major Romantics champion gold and others paper, they generally share what Robert Miles calls the “dream of achieving permanent or transcendent value against a background of value rendered radically unstable or contested” (Miles par. 10). Some Romantics also promoted bullionist ideas on a literal level. Like Cobbett, the poet Percy Bysshe Shelley thought currency the weapon of a new financial oligarchy determined to alienate honest labor, which he associated, conversely, with the stability and truth of gold (Dick, Romanticism 10). The heroine of Jane Austen’s novel Emma (1815) distrusts her new friend Harriet, whom she suspects to be an illegitimate daughter and a would-be social-climber and marriage-market speculator. Emma fears that Harriet’s marriage into the local elite would constitute an assault on time-honored social, economic, and sexual values. In Emma’s imagination, Harriet “circulates like a bank bill whose questionable legitimacy is deepened by the facility of her transference” (Miles par. 1). Emma turns out to have badly misjudged her friend, but via this plot, Austen shows how, during Restriction, fear of paper currency and forgery evolved into fear of the unregulated circulation of women. As Emma suggests, “the conceptual field in which forgery finds itself placed … is not Romanticism’s repressed secret but rather its enabling condition” (Miles par. 1). Without Restriction, the British Romantic literary tradition would not have developed as it did.

The Romantics’ preoccupation with bullion, paper currency, and financial forgery makes it unsurprising that their generation took interest in the fall of the forger Paul Whitehead. On 29 January 1812, five months before the murder of Perceval and so at the height of the bullionist controversy, Whitehead, age thirty-six, was executed by hanging at ![]() Newgate. In October 1811, he had been convicted of “feloniously forging and counterfeiting an acceptance on a certain bill of exchange” (“October 1811, trial of PAUL WHITEHEAD”). According to testimony given at his trial at London’s central criminal court, Whitehead presented a bill to banker Abraham Wildey Robarts at the Exchange in the Bank of England’s Rotunda. Robarts declined the bill, but a high-ranking clerk in his employ stepped forward to vouch for Whitehead. This clerk told Robarts that “he knew [Whitehead] very well as a clerk in the cashier’s office in the bank” and considered him a “respectable man” (“October 1811, trial of PAUL WHITEHEAD”). In fact, Whitehead had quit his job at the Bank of England in the previous year, 1810. However, Robarts trusted his employee’s testimonial and accepted Whitehead’s bill. It subsequently turned out to be a forgery. While Robarts’s clerk’s evidence impugns Whitehead, it also reflects poorly on the bankers. This moral complexity only increased after the trial, as there seems to have been some small controversy about Whitehead’s sentence. His execution was respited for five days, from 24-29 January 1812 (Digital Panopticon). Clearly, his case attracted attention and generated unease.

Newgate. In October 1811, he had been convicted of “feloniously forging and counterfeiting an acceptance on a certain bill of exchange” (“October 1811, trial of PAUL WHITEHEAD”). According to testimony given at his trial at London’s central criminal court, Whitehead presented a bill to banker Abraham Wildey Robarts at the Exchange in the Bank of England’s Rotunda. Robarts declined the bill, but a high-ranking clerk in his employ stepped forward to vouch for Whitehead. This clerk told Robarts that “he knew [Whitehead] very well as a clerk in the cashier’s office in the bank” and considered him a “respectable man” (“October 1811, trial of PAUL WHITEHEAD”). In fact, Whitehead had quit his job at the Bank of England in the previous year, 1810. However, Robarts trusted his employee’s testimonial and accepted Whitehead’s bill. It subsequently turned out to be a forgery. While Robarts’s clerk’s evidence impugns Whitehead, it also reflects poorly on the bankers. This moral complexity only increased after the trial, as there seems to have been some small controversy about Whitehead’s sentence. His execution was respited for five days, from 24-29 January 1812 (Digital Panopticon). Clearly, his case attracted attention and generated unease.

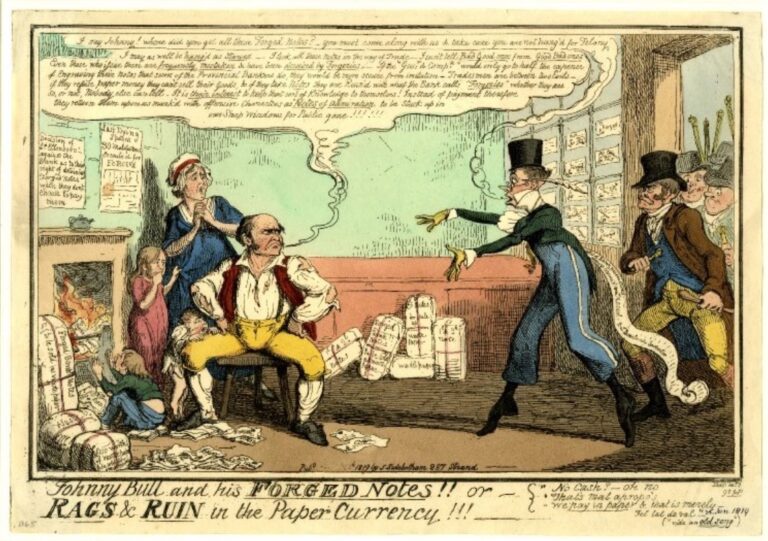

In Romantic-era print culture, Whitehead became posthumously notorious and was also symbolically feminized—the first step, I contend, in the transformation of his story into that of the Bank Nun. The sensational Criminal Recorder, or Biographical Sketches of Notorious Public Characters (1815) recounts Whitehead’s crime, conviction, and execution. Exploiting the anti-forgery panic, the Criminal Recorder does not merely present Whitehead’s forged bill as a dangerously deceptive article but also depicts Whitehead himself as a fraud. He is “a man of genteel appearance” that conceals a criminal reality, and also, as at trial, misrepresents himself to Robarts as a current Bank of England clerk “liable to lose his situation in the Bank in the event of not getting the bill cashed” (Criminal Recorder 244). In short, the Criminal Recorder’s Whitehead is himself a forgery, personifying the dangers of opaque, deceptive paper credit instruments and of the “credit” inherent in the social status of a gentleman. His disingenuous gentility also might be read as effeminacy. In 1819, George Cruikshank published the cartoon “Johnny Bull and his Forged Notes!! Or, Rags and Ruin in the Paper Currency” (Figure 4). This satire depicts what Ian Haywood calls a “ruggedly masculine” personification of working-class Britain accosted by a fashionable, venal fop representing paper currency (Haywood par. 10). In the cartoon, the fop brings constables to arrest Bull for forgery, knowing that Bull has only innocently accepted bad notes. In the cartoon, Bull is a tradesman whose honest labor contrasts with the fop’s idle capitalism. In a dialogue bubble, Bull protests that the fop has forced him to accept easily forged paper currency because otherwise he cannot sell his goods to the public. Evidently, Cruikshank’s currency-pushing fop and the Whitehead of The Criminal Reporter are the same effeminate type, suggesting that in Romantic culture, anxieties about currency and gender were inextricably mixed up.

Figure 4. George Cruikshank. “Johnny Bull and his Forged Notes!! Or, Rags and Ruin in the Paper Currency!” 1819.

The Forger’s Sister’s Tale

After Restriction, London writers exploited these interrelated anxieties by reviving Whitehead’s story but with a new focus on his sister. Neither the contemporary accounts of his trial and execution nor the Criminal Recorder mention a Whitehead sister, but it seems that there was such a woman and that she survived her brother. On 22 February 1828, the Times documented a ![]() Southwark magistrate’s examination of a “Miss Whitehead[,] well-known in the city, at the Bank and Stock Exchange particularly, which she daily perambulates […] dressed in deep mourning” (“Union-Hall” 4). Her costume includes a “black gauze” headdress and “red cheeks and lips plastered over with carmine,” emphasizing “the contrast” between “the poor woman’s artificial ruddy complexion and the sombre hue of [her] curious dress” (4). She complains that female relatives are trying to rob and poison her, but the Times blames her brother for her misfortunes. According to “an individual who was present […] about 14 years ago [1814], her brother, who was a clerk in the Bank, had been executed for forgery” (4). She is “in the constant habit of going to the Bank, where many of the gentlemen who attend there […] very liberally contribute to her aid in providing for her wants” (4). The reporter’s evaluation of her clothing and red makeup renders her a deceptive commodity. She dresses in mourning but, with her sadly synthetic rouge, aims for sex appeal. The Times insinuates that she exploits the “gentlemen” of the Bank just as did her late brother.

Southwark magistrate’s examination of a “Miss Whitehead[,] well-known in the city, at the Bank and Stock Exchange particularly, which she daily perambulates […] dressed in deep mourning” (“Union-Hall” 4). Her costume includes a “black gauze” headdress and “red cheeks and lips plastered over with carmine,” emphasizing “the contrast” between “the poor woman’s artificial ruddy complexion and the sombre hue of [her] curious dress” (4). She complains that female relatives are trying to rob and poison her, but the Times blames her brother for her misfortunes. According to “an individual who was present […] about 14 years ago [1814], her brother, who was a clerk in the Bank, had been executed for forgery” (4). She is “in the constant habit of going to the Bank, where many of the gentlemen who attend there […] very liberally contribute to her aid in providing for her wants” (4). The reporter’s evaluation of her clothing and red makeup renders her a deceptive commodity. She dresses in mourning but, with her sadly synthetic rouge, aims for sex appeal. The Times insinuates that she exploits the “gentlemen” of the Bank just as did her late brother.

Continuing controversy about forgery and its punishment make this portrait highly topical. In 1821, Restriction ended, but paper currency continued to grow in quantity and ubiquity. The period 1824-5 saw the controversial executions of two financial forgers: the well-connected Quaker Joseph Hunton and debonair clerk Henry Fauntleroy. Both Hunton and Fauntleroy were objects of massive public fascination and pity in life and death. In fact, outrage about their executions contributed to the reform of forgery punishment, which Parliament enacted in 1832. In that year of the Great Reform, Parliament abolished the death penalty for most forgery offences. Total abolition of execution for forgery followed in 1837. Therefore, in 1828, when the Times reporter encountered Miss Whitehead, forgery was a reviled capital crime, but forgers and their families excited pity, too. Both sides of this emotional tug-of-war shine through the Times article’s representation of the late Paul Whitehead’s sister.

After that article’s publication, Miss Whitehead glides out of recorded history as subtly as she entered it. As Martin Meisel points out, in April 1831, a similar character, “the Old Lady in Black, Mrs. Bankington Bombasin,” who pesters “the Expectation Office” to give her a lost West Indian fortune, appeared in a play at the Adelphi, “The New Diapolologue ‘No. 26 and No. 27, or Next Door Neighbors,” a “playlet” (Meisel 278). Notably, Miss Bombasin has no connection with forgery or execution. On the real Miss Whitehead’s further adventures, the archival record is rather inconclusive. An Eliza Whitehead died on 9 November 1837 and was buried at ![]() Spa Fields, Islington, but she cannot be our heroine, as she was an infant (Registers 1837-57). A more promising possibility is Phoebe Whitehead, a “single” destitute “laundress” born in

Spa Fields, Islington, but she cannot be our heroine, as she was an infant (Registers 1837-57). A more promising possibility is Phoebe Whitehead, a “single” destitute “laundress” born in ![]() Holborn in 1788. Age twenty-five at the time of Paul Whitehead’s execution, this woman was admitted to Southwark’s

Holborn in 1788. Age twenty-five at the time of Paul Whitehead’s execution, this woman was admitted to Southwark’s ![]() Christchurch Workhouse on three occasions in 1837-39 (Workhouse Admission and Discharge Records, 1764-1930). A Phoebe Whitehead, though not necessarily the same woman, exited the Christchurch Workhouse on 29 September 1846 “to go to Service” and again on 3 March 1848 (Workhouse Admission and Discharge Records, 1764-1930). Finally, the 1851 Census locates Phoebe Whitehead, a “single…pauper,” at another Southwark workhouse,

Christchurch Workhouse on three occasions in 1837-39 (Workhouse Admission and Discharge Records, 1764-1930). A Phoebe Whitehead, though not necessarily the same woman, exited the Christchurch Workhouse on 29 September 1846 “to go to Service” and again on 3 March 1848 (Workhouse Admission and Discharge Records, 1764-1930). Finally, the 1851 Census locates Phoebe Whitehead, a “single…pauper,” at another Southwark workhouse, ![]() St. George the Martyr. If any of these records describe the forger’s sister, the Bank did not save her from destitution.

St. George the Martyr. If any of these records describe the forger’s sister, the Bank did not save her from destitution.

Whatever her fate, Victorian writers, artists, and gossips reinvented her as a monstrous product of the metropolitan economies of financial and sexual credit who subverts masculine institutions and authorities. As far as I can tell, the earliest surviving published depiction of Miss Whitehead postdating the Times article and Miss Bombasin is “The Bank Nun, A Black Note, with Red Signature,” the third installment in the Pickwickian sketch collection Streetology of London: Or, the Metropolitan Papers of the Itinerant Club, which was printed, only once, in 1837. This was a year not only when capital punishment for forgery was finally, controversially banned, but of financial crisis. The “Panic of 1837” began in the ![]() United States but affected Britain on account of British investment in American business. Banks failed, producing deep distrust of speculation and credit (Dimsdale and Hotson 34-5; Lepler 57-60). This distrust deepened with sensational revelations of white-collar crime. For instance, when Manchester’s

United States but affected Britain on account of British investment in American business. Banks failed, producing deep distrust of speculation and credit (Dimsdale and Hotson 34-5; Lepler 57-60). This distrust deepened with sensational revelations of white-collar crime. For instance, when Manchester’s ![]() Northern and Central Bank lost the money it had invested in American interests, its Directors were found to have embezzled £200,000 (Acres 463-6). The national panic primed the reading nation to evaluate the trustworthiness of banking, credit, and paper money. Streetology delivers such an evaluation, conceding that paper currency invites forgery but ultimately vindicating the Bank of England as a moral force.

Northern and Central Bank lost the money it had invested in American interests, its Directors were found to have embezzled £200,000 (Acres 463-6). The national panic primed the reading nation to evaluate the trustworthiness of banking, credit, and paper money. Streetology delivers such an evaluation, conceding that paper currency invites forgery but ultimately vindicating the Bank of England as a moral force.

To make this argument, Streetology depicts the executed forger’s criminality re-emerging in his sister. Set in 1812, the year of Paul Whitehead’s execution, Streetology purports to be “edited” by one “Jack Rag, Knight of the Street Cross Sweepers’ Society” from the memoirs of a Regency sweeper and absconded Bermondsey apprentice, Richard “Dickey” Tynt (Streetology 1). The sketch is a picaresque adventure that recounts Tynt’s financial education. It begins with Tynt setting off for the Bank of England to invest his meagre life savings, a jumble of coins tied up in a stocking, in the stock market. Is this a wise decision? En route, Tynt meets the “trickster” ‘Captain’ Naylor, who practices “the art and mystery of dishonesty by which,” like an alchemist, he “turn[s] all [his] victims into gold” (33). Naylor steals a naïve visiting Yorkshireman’s check, accuses the victim of having forged it, and schemes to fob it off on another victim. This shady character finds a double in “Miss Sarah Whitehead […] of Bank Notoriety,” or “The Bank Nun” (41). Naylor tells Tynt that Miss Whitehead is a kind of a con artist, just like him. Since her brother’s execution for forgery, she has fraudulently lived on the proceeds of her bullying of Bank of England employees and City financiers, including the famous Baron Rothschild (45). This makes those financiers seem humanitarians.

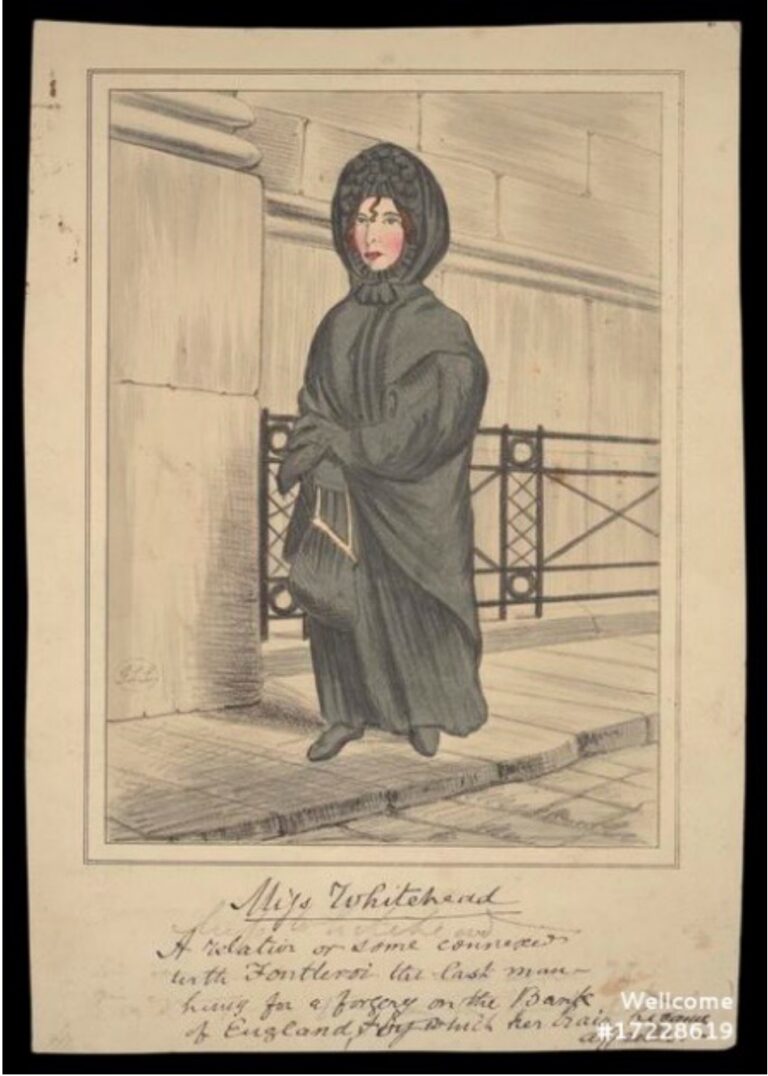

Streetology also depicts the Bank Nun as a forgery and a forger, just like her brother as remembered by the Criminal Recorder. In Victorian fiction, “female fakes” often conspire with art forgers, not as fellow fraudsters, but as forgeries (Briefel 71). In keeping with this trend, Streetology’s illustration of the Bank Nun, engraved by George L. Lee, includes a caption that renders her a living forged check:

The Check you behold by a Whitehead was drawn,

On the Bank of Old England, ‘tis true;

Some say‘t was dishonoured and noted with red,

And atWalworth now lies over due. (Streetology 32)

Sexually “dishonoured,” she “lies” pregnant and past her due date in Walworth, Southwark. Her child will be illegitimate, just as was her brother’s financial forgery. In Streetology’s text, Naylor concurs with this insinuation. He tells Tynt that Miss Whitehead was jilted by a lover, whose identity Naylor refuses to reveal. “[D]elicate points connected with her life” might “rankl[e] the feelings of her friends, if she has any,” Naylor claims, but “unrequited love […] assisted the melancholy that […] took possession of her” (41): she has gone mad because she is abandoned by her brother on account of his death and by her lover. With this elaboration upon the Times’s Miss Whitehead’s predicament, Streetology reviles its heroine as a woman who has transgressed sexual boundaries and threatens to adulterate society with the product of her transgression. As Sara Malton’s monograph on financial forgery in Victorian literature demonstrates, Victorian fiction is deeply indebted to cultural memory of the Restriction era’s moral panic about forgery, which many Victorians remembered as an attack on their own society’s institutions and values (Malton 3). One way in which this focus manifests in Victorian fiction is the frequent representation of the “fallen woman” as “a kind of forger,” with “her illegitimate [child] a kind of spurious production” (6). This analogy shapes Elizabeth Gaskell’s Ruth (1853), which enlists it only to defend its eponymous heroine against the predatory practices of Victorian patriarchy (60-5). Earlier, in Streetology, the Bank Nun is an unsympathetic version of the fallen woman as forger. Her unauthorized sexual reproduction poses as serious a danger to social and economic order as does her era’s epidemic of financial forgery.

In fact, fear of the uncontrolled circulation of women fuels Streetology’s christening of Miss Whitehead as “the Bank Nun.” Notably, the Times article does not identify Miss Whitehead’s black garments with a nun’s habit. In 1828, a nun would have been a strange sight in England. In 1829, however, Parliament enacted Catholic Emancipation, which liberated English Catholics to practice their faith without exclusion from major institutions such as the universities, the professions, and Parliament. Many Protestants disapproved, and so in the early days of Emancipation, anti-Catholic sentiment was rife and Protestant media called nuns dangerous to conventional family structures (Kollar 19). Consider, for instance, an inheritance dispute discussed in the British Magazine and Monthly Register of Religious and Ecclesiastical Information (1848). Two Irish Ursulines sued their brother after he denied them a share of their late father’s fortune. After extended litigation, he won. Condemning the “cupidity of the convent,” the British Magazine opines that “simply […] as nuns,” the sisters cannot participate in the economy. “Any deed executed by them” is “utterly null and void” because:

… the member of one of these religious orders ceases to be a free agent in the distribution of any property that may devolve upon her, and becomes enslaved by the rules and regulations of the community, without any possibility of relieving herself from the dominion of the vows thus taken upon her. (“Modern Monasticism” 201)

Curiously, the “vows” that in this account threaten to negate women’s agency do not include marital ones. Rather, Anglicans feared nuns’ Catholicism and their refusal of domestic patriarchy. In this cultural milieu, the nickname “the Bank Nun” associates Miss Whitehead with a form of female transgression that appeared to be making a real-life comeback.

In short, Streetology’s Bank Nun is a dangerously self-circulating female fraud who robs a masculine, passive, and even charitable Bank. Her story as narrated by Naylor teaches Tynt not to trust paper credit nor women. Both, Tynt learns, are chaotically circulating, easily adulterated, deceptive items of unstable value, just as they had seemed to many Britons in the 1810s. Tynt’s composition of his memoirs for the edification of Londoners of a later era carries Restriction-era fears well beyond Victoria’s coronation.

The Forger’s Brother’s Tale

As the Victorian era progressed, the Bank Nun escaped from the pages of Streetology to be canonized as a historical figure. This may have happened because, perhaps in spite of the anonymous author’s intentions, the notion of the Bank Nun magnetized common frustrations with the banking industry and so people may have on some level wished the story to turn out to be substantially true. In a Blackwood’s review of 1837, the anonymous critic calls Lee’s illustration “an exact likeness of the lady” (Blackwood’s 149). Like this reviewer, other commentators began to insist that the Bank Nun was a real person and a kind of provocateur of the finance world. The Lee portrait and a nearly verbatim extract of the Streetology sketch’s text were reproduced as the Memoirs, Extraordinary Life, and Singular Adventures of that Eccentric Character, Miss Whitehead, the Bank Nun, with Numerous Anecdotes and Interesting Particulars of the Awful Death of her Brother (1837), the book pictured in Emma Clery’s tweet from the Bank of England Museum.

Soon thereafter, the Bank Nun acquired a key indicator of historical actuality: a specific date of death. In 1841 appeared William D. Reider’s chronicle The New Tablet of Memory, or Recorder of Remarkable Events, Alphabetically Arranged. Reider includes events from “earliest times,” such as the reign of the First Emperor of China and the founding of the ![]() University of Cambridge, but also a good number of events that he claims took place in London during the early nineteenth century. He claims to have written these down while they were still current events. He has “devoted above thirty of” his “earlier years … to the recording of passing events” (Reider vi). His alphabetical organizational schema prevents any comprehension of his work as linear history, exploding any attempt on the reader’s part to make causal connections between the events he catalogues. However, it allows the reader to experience history’s eclectic occurrences and characters as a phantasmagorical spectacle. Within this nonlinear parade of events, the death of “Miss Whitehead (known as the ‘Bank Nun’)” prominently stands out. Much of the entry echoes Streetology and the plagiarized Memoir, but Reider also builds his story up to a momentous death. On “the day of Her Majesty’s (Queen Victoria), visit to the Civic Banquet, on Thursday, November 9, 1837, this poor maniac had persuaded herself that she was to be one of the Lord Mayor’s guests” (Reider 549). This planned disruption of official ritual was narrowly averted, Reider claims, because on “that memorable day—she breathed her last!” (549, emphasis original) and was positively identified by the City Coroner, who had known her “from his youth,” and by various other Londoners long familiar with her antics (550). The New Tablet’s generic identity as a work of “history,” its citation of named witnesses to the Bank Nun’s career, and, especially, its precise dating of her death render her an emphatically actual bugbear of metropolitan officialdom.

University of Cambridge, but also a good number of events that he claims took place in London during the early nineteenth century. He claims to have written these down while they were still current events. He has “devoted above thirty of” his “earlier years … to the recording of passing events” (Reider vi). His alphabetical organizational schema prevents any comprehension of his work as linear history, exploding any attempt on the reader’s part to make causal connections between the events he catalogues. However, it allows the reader to experience history’s eclectic occurrences and characters as a phantasmagorical spectacle. Within this nonlinear parade of events, the death of “Miss Whitehead (known as the ‘Bank Nun’)” prominently stands out. Much of the entry echoes Streetology and the plagiarized Memoir, but Reider also builds his story up to a momentous death. On “the day of Her Majesty’s (Queen Victoria), visit to the Civic Banquet, on Thursday, November 9, 1837, this poor maniac had persuaded herself that she was to be one of the Lord Mayor’s guests” (Reider 549). This planned disruption of official ritual was narrowly averted, Reider claims, because on “that memorable day—she breathed her last!” (549, emphasis original) and was positively identified by the City Coroner, who had known her “from his youth,” and by various other Londoners long familiar with her antics (550). The New Tablet’s generic identity as a work of “history,” its citation of named witnesses to the Bank Nun’s career, and, especially, its precise dating of her death render her an emphatically actual bugbear of metropolitan officialdom.

Another Victorian writer who saw the Bank Nun’s potential for provocation was James Malcolm Rymer (1814-84). Rymer grew up in a family of working-class writers and artists, including his father, Malcolm Rymer, an engraver, poet, and novelist who published in radical journals during the era of Romanticism and Restriction (Nesvet, “Blood Relations”). In such a community, familiarity with Cobbett’s Political Register would have been virtually obligatory. Moreover, James Malcolm Rymer had a personal reason to be intrigued by the story of the financial forger Whitehead and his sister. One must not “envy” any man, Rymer wrote in his novel Family Secrets, or, A Page from Life’s Volume (1846), “for Heaven and himself only knows what skeleton he may have in his house” (Rymer, Family Secrets, “Preface” n.p.). His own domestic skeleton was his brother Thomas, who in 1838 was convicted of “feloniously engraving, without authority, part of a Bank-note” and “feloniously and knowingly uttering a forged £5 Bank-note” (“Trial of Thomas Rymer”). For these crimes, Thomas Rymer was transported to ![]() Van Diemen’s Land for life (Collins). In Van Diemen’s Land and on the Australian mainland, Thomas Rymer was convicted of additional banknote forgeries, with his final conviction recorded in

Van Diemen’s Land for life (Collins). In Van Diemen’s Land and on the Australian mainland, Thomas Rymer was convicted of additional banknote forgeries, with his final conviction recorded in ![]() Sydney in 1865 (Nesvet, Science and Art). Thomas’s fate evidently preoccupied his brother. Forgery features prominently in James Malcolm Rymer’s penny fiction, including Jane Shore (1842-6), Ada, the Betrayed, or the Murder at the Old Smithy (1843), Family Secrets, or A Page from Life’s Volume (1846), Varney, the Vampire, or the Feast of Blood (1847), The Lady in Black (1847-8), Kate Chudleigh, Duchess of Kingston (1864), and A Marriage of Mystery, or, the Lost Bride (1868). The topic haunted him as much as it intrigued his readers.

Sydney in 1865 (Nesvet, Science and Art). Thomas’s fate evidently preoccupied his brother. Forgery features prominently in James Malcolm Rymer’s penny fiction, including Jane Shore (1842-6), Ada, the Betrayed, or the Murder at the Old Smithy (1843), Family Secrets, or A Page from Life’s Volume (1846), Varney, the Vampire, or the Feast of Blood (1847), The Lady in Black (1847-8), Kate Chudleigh, Duchess of Kingston (1864), and A Marriage of Mystery, or, the Lost Bride (1868). The topic haunted him as much as it intrigued his readers.

All the Rymer titles mentioned thus far are examples of penny fiction, or illustrated novels targeting working-class readers and so disseminated serially in periodicals or as runs of slim standalone “parts” for a penny per number. This type of literature flourished circa 1830-90, but particularly at midcentury. Long derided as “penny bloods” (circa 1830-60) and less lurid, later “dreadfuls,” penny fiction is now understood as a complex and nuanced body of work often informed by radical ideas and an important tool in Victorian working-class political awakening. As critics have now established, Rymer’s usually anonymous or pseudonymous penny fiction was some of the most commercially successful, celebrated, and enduring of the Victorian penny press. Among his villains are Varney the Vampyre, antihero of a novel that in many ways anticipates Dracula (1897) by half a century and Sweeney Todd, the homicidal ![]() Fleet Street barber. Rymer invented Varney and Todd for the publishing firm of the Chartist Edward Lloyd. The professional coterie of writers that Lloyd gathered to write for his firm were sometimes collectively known as “the Salisbury Square School,” after Lloyd’s operation’s premises at

Fleet Street barber. Rymer invented Varney and Todd for the publishing firm of the Chartist Edward Lloyd. The professional coterie of writers that Lloyd gathered to write for his firm were sometimes collectively known as “the Salisbury Square School,” after Lloyd’s operation’s premises at ![]() no. 12 Salisbury Square, off Fleet Street. Many middle-class critics reviled Lloyd’s output, insisting that it dangerously glorifies criminality and corrupts impressionable working-class minds, especially those of young boys, preparing them for lives of crime and violence. However, this did not deter the penny press’s numerous readers.

no. 12 Salisbury Square, off Fleet Street. Many middle-class critics reviled Lloyd’s output, insisting that it dangerously glorifies criminality and corrupts impressionable working-class minds, especially those of young boys, preparing them for lives of crime and violence. However, this did not deter the penny press’s numerous readers.

Rymer’s penny novel The Lady in Black, or, the Widow and the Wife (1847-8), reinvents Streetology’s narrative of the Bank Nun’s biography to question his society’s continued demonization of forgery, the banking industry’s practices, and the politics of class. To begin with, Rymer recycles the Lee illustration as a woodcut, but does not call his heroine “the Bank Nun.” Instead, he denominates her “the Lady in Black” (Rymer, The Lady in Black 13), a name reminiscent of Shakespeare’s muse, the Dark Lady. Rymer also renames her. He calls her “Marian Whitehead,” a name reminiscent of Robin Hood’s lady love Maid Marian. In the 1840s, as Stephen Basdeo has shown, Lloyd published a radical depiction of Robin Hood and Maid Marian: Pierce Egan, junior’s penny serial Robin Hood and Little John, or, the Merry Men of Sherwood Forest (1838-40), which proved a bestseller (Basdeo). Like Egan’s Maid Marian, Rymer’s Marian Whitehead is a faithful lover of a moral man misunderstood and persecuted as a criminal. Her troubles begin with her love for an industrious young City clerk, Charles Ormond. At work at the firm of merchant trader Simon Godfrey, Ormond tries to prevent his theft of the money that Marian’s late father made working in ![]() India. Godfrey finds out and punishes Ormond by firing him. Via this plot point, Rymer dispenses with the negative associations of the historical Paul Whitehead’s having been let go by the Bank. Marian’s mother shelters the unemployed Ormond, giving him “an apartment to himself,” where he lives “as a brother to Miss Marian” (Rymer, Lady 184). This convoluted explanation absolves Marian Whitehead of Streetology’s accusations of sexual immorality and Gothic pseudo-nunhood. To the outside world, Marian appears to be a fallen woman who is unredeemable after her lover’s execution. Rymer insists that this is a misconception. His Marian Whitehead is neither fake, deceptive, nor promiscuous. In fact, as the novel’s subtitle the Widow and the Wife indicates, she is a thoroughly domesticated woman in her paradoxical status as both Ormond’s mournful widow and devoted wife.

India. Godfrey finds out and punishes Ormond by firing him. Via this plot point, Rymer dispenses with the negative associations of the historical Paul Whitehead’s having been let go by the Bank. Marian’s mother shelters the unemployed Ormond, giving him “an apartment to himself,” where he lives “as a brother to Miss Marian” (Rymer, Lady 184). This convoluted explanation absolves Marian Whitehead of Streetology’s accusations of sexual immorality and Gothic pseudo-nunhood. To the outside world, Marian appears to be a fallen woman who is unredeemable after her lover’s execution. Rymer insists that this is a misconception. His Marian Whitehead is neither fake, deceptive, nor promiscuous. In fact, as the novel’s subtitle the Widow and the Wife indicates, she is a thoroughly domesticated woman in her paradoxical status as both Ormond’s mournful widow and devoted wife.

While Rymer exonerates Miss Whitehead of promiscuity, artifice, pretension to monastic calling, and association with actual forgery, he zeroes in on what he contends constitutes the real corruption in Threadneedle Street: that of the financial community. When Godfrey fires Ormond, he induces that clerk to accept his final wages as a check. Playing a trick identical to Streetology’s Naylor’s deception of the Yorkshireman, Godfrey makes the check out to look forged. Because this financial instrument is worth exactly what Godfrey owes Ormond, had Ormond forged it as accused, economic justice would have been served. Instead, when Ormond presents it at the Bank, he is arrested for forgery. He explains about his firing, but no one cares that Godfrey has stolen Ormond’s labor’s value. Ormond’s objection falls upon deaf ears because British law does not exist to protect working men. Reinforcing this point, Rymer declares “forgery makes no call upon general and public indignation,” but victimizes “only those who have directly suffered […] in pocket by the attempt of the criminal,” not “aggravat[ing]” the “multitude […] however really great an [sic] one it [the victim] is in a social point of view” (Rymer, Lady 127-33). At Ormond’s trial, the prosecutor affirms that forgery harms mainly “the mercantile community” and argues that Ormond must die to set an example to other employees who might defraud their employers. Forgers have “enormous power […] even of irretrievably ruining their employers […] utterly destroy[ing] the thousands of families who depend upon the prosperity of that merchant or trader for employment — for bread,” he argues (159). “[T]he great necessity of there existing between the employer and the employed a bond of union” makes Ormond’s supposed “offence” a “public one,” which must be “punished accordingly by the public” (159). However, in the world of The Lady in Black, employer and employee share no bond. This implies that forgery does not in fact harm the people and so should not be punished as a public offense. Its not so long-ago punishment by death proves that class oppression is baked into British law.

Having reappraised Restriction-era financial forgery prosecution, Rymer recasts the developing urban myth of the Bank Nun as a tool of working-class resistance. After Ormond’s execution, Marian Whitehead dons mourning. As in Reider’s account (“poor maniac”) she goes mad and wanders the city for decades. Devastated, aging, and homeless, she is run down in the street by an opulent carriage. This final elite atrocity galvanizes her to lucid thought and righteous action. Brought indoors to recuperate by a charitable Cockney cheesemonger, Miles Atherton, Marian sends Godfrey not the “curses” he expects, but her “forgiveness” (553-4). She gives Atherton a portfolio of documents that reveal her tragic history. With her dying words, she authorizes Atherton to publish the documents in fifteen years’ time; that is, on 9 November 1845 (9; see also 18, 30). Her death on 9 November 1830 occurs on the same day and month as in Reider’s Tablet of Memory, though the year is different. The fifteen-year embargo to which Marian Whitehead binds Atherton implies that all depictions of her predating 1845 are unauthorized and untrustworthy. Such accounts must of course include Streetology and its earliest plagiarisms, including Reider’s. Marian’s selection of Atherton as her archivist and publisher renders her story the intellectual property of London’s working-class. She turns her life story into a tool that Atherton’s class might deploy against its oppressors; especially against the gatekeepers of the credit economy.

Like the Streetology sketch, The Lady in Black captured the Victorian imagination. As Meisel explains, Charles Dickens repeated the Bank Nun’s story in an 1853 contribution to Household Words. Like Rymer, Dickens finds her “a poor demented woman” (Dickens 361, quoted in Meisel 1966), although, as in Streetology, the executed clerk is her brother, not her suitor. In 1880, novelist and activist Thomas Frost remembered Rymer’s The Lady in Black as a “thrilling romance” and one of “the most successful of the Salisbury Square fictions” (Frost 94). Noting that The Lady in Black is based on “the well-known story of a young lady who lost her reason through the execution for forgery of her brother, a clerk in the Bank of England,” Frost finds its heroine deeply sympathetic, calling her “a pale, thin figure, waiting for the brother she would never see again” (94). In 1848, the playwright Charles Alfred Somerset dramatized the novel as The Lady in Black; or the Nun of the Bank. This play superimposes Rymer’s narrative upon Streetology’s icon (Lord Chamberlain’s Plays; Nicoll 395). A radical writer, Somerset later composed The Life and Struggles of the Working Man (1853), adapted from a novel by Émile Souvestre (Lord Chamberlain’s Plays). Canonical Victorian literature also borrows from Rymer’s novel, echoing its politics to some extent. Ross, the cartoonist who claimed to have witnessed the Bank Nun’s vigil, identifies The Lady in Black as an antecedent of Wilkie Collins’s 1859 novel The Woman in White (Ross 87), which, as Malton argues, “implicat[es] forgery in the fallibilities of the law” (Malton 31), just like The Lady in Black does. Rymer’s Miss Whitehead could therefore be said to haunt Collins’s canonical novel.

A “Wonderful Character”

After Rymer and Collins, the Bank Nun continued her hold on the London metropolitan imagination, generally accepted as a historical figure. An 1869 revision of the Regency Book of Wonderful Characters includes a sketch of Miss Whitehead, complete with moniker “the Bank Nun” and a reproduction of Lee’s caricature (Wilson and Caulfield 36-9).[2] The text is a condensation of the Streetology sketch, but without the Dickey Tynt frame, Captain Naylor, or the original’s harshest criticisms of the Bank Nun. No longer a deceptive fake nor a venal fallen woman, this Bank Nun is merely one of the theatrical iconoclasts or “wonders” that makes metropolitan life a constantly engrossing piece of street theatre. A similar attitude pervades a brief unpublished commentary on the Bank Nun in the medical history collection of American pharmaceutical baron Henry Solomon Wellcome (1853-1936). At an undetermined date, Wellcome added a copy of Lee’s portrait of the Bank Nun to his massive collection, a good portion of which concerns madness and its treatment. In the margins of this print, an undated handwritten note mistakenly identifies the Bank Nun as “a relation or some connexed with Fontleroi [sic] the last man hung for a forgery on the Bank of England” (Figure 5). As the annotator understood the Bank Nun, she is a figure of pathos, as she was for Rymer. Her elaborate mourning for a man whose execution was perhaps excessive drives her mad.

Figure 5. George L. Lee. “Miss Whitehead.” Used with permission. Wellcome Collection, London. Copyright 2019, the Wellcome Collection.

Subsequent writers imported the Bank Nun into the twentieth century. One was the Modernist poet and socialite Edith Sitwell (1887-1964). The daughter of Sir George Sitwell and granddaughter of the Earl of Lonsdale, Sitwell proudly claimed descent from the Plantagenet kings of medieval England. As an adult, she formed a close kinship coterie with her two younger brothers, Sir Osbert Sitwell (1892-1969) and Sir Sacherevell Sitwell (1897-1988). Many of her more prominent literary colleagues did not take her seriously. According to her critical biographer Jean Radford, the Cambridge literary critic F.R. Leavis claimed that the three Sitwell siblings “belong more to the history of publicity [celebrity] rather than the history of poetry” (Radford 203). More diplomatically, Radford calls Sitwell what she called herself: an “eccentric”; that is, someone who expresses “criticism of the world’s arrangement” via only “one gesture, and that of sufficient contortion” (Sitwell 22). Radford considers this type “what we might now call a “performance artist” (Radford 203). In 1933, Sitwell published a book titled English Eccentrics. Billed as a compendium of historical eccentrics, it is also a meandering Modernist prose poem. Its portrait of the Bank Nun derives from the 1869 Book of Wonderful Characters but also idealizes its heroine as poetically as Rymer does. Sitwell lauds “Sarah Whitehead, known as the Bank Nun” as an icon of “the thoughts of that heaven of love that survives material death” (Sitwell 30). Loving her brother in spite of law, reason, and death, she is “one of the angels of that heaven” (Sitwell 30). In Sitwell’s telling, a naïve seventeen-year-old “Sarah Whitehead…did not hear the bell of ![]() St. Sepulchre’s Church tolling for the death of” her brother, “who had been hanged for forgery” (32). Like Rymer’s Ormonde, he is innocent. He is executed “only three days after he was condemned to death, whilst the man who was guilty” of the forgery “went free” (33). This makes Miss Whitehead’s Threadneedle-Street protest a critique of the prosecution of forgery or of the justice system entire, as in Rymer’s account. However, if Sitwell’s retelling owes anything directly to The Lady in Black, she discards Rymer’s political agenda. The aristocratic Sitwell was a Bohemian and a Modernist, but no labor activist nor pursuer of political justice. According to Radford, she consistently “held the view that art should remain distinct from politics” and opposed British military resistance to Continental Fascism (Radford 212). Having largely depoliticized the Bank Nun, Sitwell passed her on to her friend Auden. In writing New Year’s Letter, he derived the myth from her English Eccentrics (Emig 153), but in his telling, the Bank Nun loves a “hanged embezzler,” not an innocent man framed for forgery. Auden’s retelling weaves together those strands of the urban legend in which the man the Bank Nun mourns is unjustly martyred and those in which he is guilty of financial forgery.

St. Sepulchre’s Church tolling for the death of” her brother, “who had been hanged for forgery” (32). Like Rymer’s Ormonde, he is innocent. He is executed “only three days after he was condemned to death, whilst the man who was guilty” of the forgery “went free” (33). This makes Miss Whitehead’s Threadneedle-Street protest a critique of the prosecution of forgery or of the justice system entire, as in Rymer’s account. However, if Sitwell’s retelling owes anything directly to The Lady in Black, she discards Rymer’s political agenda. The aristocratic Sitwell was a Bohemian and a Modernist, but no labor activist nor pursuer of political justice. According to Radford, she consistently “held the view that art should remain distinct from politics” and opposed British military resistance to Continental Fascism (Radford 212). Having largely depoliticized the Bank Nun, Sitwell passed her on to her friend Auden. In writing New Year’s Letter, he derived the myth from her English Eccentrics (Emig 153), but in his telling, the Bank Nun loves a “hanged embezzler,” not an innocent man framed for forgery. Auden’s retelling weaves together those strands of the urban legend in which the man the Bank Nun mourns is unjustly martyred and those in which he is guilty of financial forgery.

Today, this multifaceted Bank Nun is the version that survives in London lore. A ghost tour currently in operation locates the Bank Nun’s spirit in Threadneedle Street and interprets her as a figure of both pathos and vengeance; deception and reliability. The tour’s publicity claims that the Bank curtailed the spirit’s “daily disturbances” by bribing her “never to return,” but “her wraith [spirit] has broken” that agreement “many times” (Jones). In death as in life, she is as untrustworthy as a Restriction-era banknote, but consistently, predictably, perhaps even reassuringly so. Regimes and banks may come and go, but at the heart of the banking district, the notion of the Bank Nun endures. As the Bank of England Museum’s Twitter thread indicates, her captivating story and deceptively specific death date combine to make her supposed Threadneedle Street campaign appear to be a historical event. Although this event is evidently fictional, when plotted on a timeline such as the BRANCH Collective’s, it might render the Bank Nun a boundary figure bridging two eras, such as the Hanoverian period and Victoria’s reign or the dark times when forgers risked execution and the comparatively enlightened but still fearful period that followed. Above all, in the twenty-first century, the Bank Nun remains a ghostly reminder of Restriction-era fears of the circulation of paper credit, financial forgery, and women.

published July 2020

HOW TO CITE THIS BRANCH ENTRY (MLA format)

Nesvet, Rebecca. “Miss Whitehead, ‘The Bank Nun'”. BRANCH: Britain, Representation and Nineteenth-Century History. Ed. Dino Franco Felluga. Extension of Romanticism and Victorianism on the Net. Web. [Here, add your last date of access to BRANCH].

WORKS CITED

Acres, William Marston. The Bank of England from Within, 1694-1900, 2 vols. Oxford UP, 1931.

Alborn, Timothy. All That Glittered: Britain’s Most Precious Metal from Adam Smith to the Gold Rush. Oxford UP, 2019.

Auden, W.H. Collected Poems, edited by Edward Mendelson, Modern Library, 2007.

Basdeo, Stephen. “Radical Medievalism: Pierce Egan the Younger’s Robin Hood, Wat Tyler, and Adam Bell.” Leeds Working Papers in Victorian Studies, vol. 15, 2016, pp. 48-65.

Benchimol, Alex. “Knowledge Against Paper: Forgery, State Violence, and Radical Cultural Resistance in the Romantic Period.” Romantic Circles and the Credit Crunch: A Romantic Circles Praxis Volume, edited by Ian Haywood, 2012. Accessed 23 May 2018.

Briefel, Aviva. The Deceivers: Art Forgery and Identity in the Nineteenth Century. Cornell UP, 2006.

Collins, Dick. “Thomas Rymer.” [comment.] Convict Records. Accessed 23 May 2018.

The Criminal Recorder: or, Biographical Sketches of Notorious Public Characters, 2 vols. R. Dowson, 1815. Archive.org.

Crosby, Mark. “The Bank Restriction Act (1797) and Banknote Forgery.” BRANCH: Britain, Representation and Nineteenth-Century History, edited by Dino Franco Felluga. Extension of Romanticism and Victorianism on the Net. Accessed 18 Nov. 2019.

Cruikshank, George. “Johnny Bull and his Forged Notes!! Or, Rags and Ruin in the Paper Currency!” J. Sidebotham, 1819. Courtesy the British Museum. Accession no. 1868,0808.8409.

Dick, Alex. “‘The Ghost of Gold’: Forgery Trials and the Standard of Value in Shelley’s ‘The Masque of Anarchy.’” European Romantic Review, vol. 18, no. 3, 2007, pp. 381-400.

——— . Romanticism and the Gold Standard: Money, Literature, and Economic Debate in England, 1790-1830. Palgrave Macmillan, 2013.

Dickens, Charles. “Where We Stopped Growing.” Household Words (1 January 1853): 361-363.

Dimsdale, Nicholas, and Anthony Hotson. “Financial Crises and Economic Activity in the UK Since 1825.” British Financial Crises Since 1825, edited by Nicholas Dimsdale and Anthony Hotson, Oxford UP, 2014, pp. 24-58.

Emig, Rainer. W.H. Auden: Towards a Postmodern Poetics. Macmillan, 2009.

Frost, Thomas. Forty Years’ Recollections: Literary and Political. Sampson Low, Marston, Searle, and Rivington, 1880.

Gillray, James. “Political Ravishment, or The Old Lady of Threadneedle-street in Danger!” 1797. Wikimedia Commons.

Haywood, Ian. “Paper Promise: Restriction, Caricature, and the Ghost of Gold.” Romantic Circles and the Credit Crunch: A Romantic Circles Praxis Volume, edited by Ian Haywood, 2012. Accessed 23 May 2018.

Jones, Richard. “The Bank of England Ghost: Have You Seen my Brother?” London Ghost Walks. Accessed 23 May 2018.

Kollar, Rene. A Foreign and Wicked Institution? The Campaign Against Convents in Victorian England. James Clarke, 2011.

Lee, George L. “Miss Whitehead.” [Colored print.] The Wellcome Collection, London. Accession no. 17228619.

Léger St.-Jean, Marie. Price One Penny: Cheap Literature 1837-1860. www.priceonepenny.info. Accessed 23 May 2018.

Lepler, Jessica M. The Many Panics of 1837: People, Politics, and the Creation of a Transatlantic Financial Crisis. Cambridge UP, 2013.

“Literature, Reviews, &c.”, Blackwood’s Lady’s Magazine and Gazette of the Fashionable World, or, St. James’s Court Register, vol. 3, 1837, p. 149.

British Library. Lord Chamberlain’s Plays, May-June 1848, Part 2: May 1848 – Jun. 1848. Add MS 43012 P2’. NCCO. Accessed 23 May 2018.

——— . Lord Chamberlain’s Plays, 1852-1858. Add MS 52953 Q’. NCCO. Accessed 23 May 2018.

London Metropolitan Archives. “Workhouse Admission and Discharge Records.” Ancestry.com Accessed 23 May 2018.

London, National Archives, “General Register Office: Registers of Births, Marriages and Deaths surrendered to the Non-Parochial Registers Commissions of 1837 and 1857.” Ancestry.com. Accessed 23 May 2019.

Malton, Sara. Forgery in Nineteenth-Century Literature and Culture: Fictions of Finance from Dickens to Wilde. Palgrave Macmillan, 2009.

Memoirs, Extraordinary Life, and Singular Adventures of that Eccentric Character, Miss Whitehead, the Bank Nun. J. Thompson, 1837.

Meisel, Martin. “Miss Havisham Brought to Book.” PMLA 81, no. 3 (1966): 278-285.

Miles, Robert. “Emma and Bank Bills: Romanticism and Forgery.” Romantic Circles and the Credit Crunch: A Romantic Circles Praxis Volume, edited by Ian Haywood, 2012. Accessed 10 May 2018.

“Modern Monasticism.” The British Magazine and Monthly Register of Religious and Ecclesiastical Information, vol. 34, no. 8, 1 Aug. 1848, pp. 197-214.

National Archives, “England Census Database for 1851.” Ancestry.com. Accessed 23 May 2018.

Nesvet, Rebecca. “The Bank Nun’s Tale: Financial Forgery, Gothic Imagery, and Economic Power.” Victorian Network, vol. 8, 2018, pp. 28-47.

——— . “Blood Relations: Sweeney Todd and the Rymers of London.” Notes and Queries, vol. 64, no. 1, 2017, pp. 112-116.

Nicoll, Allardyce. A History of Early Nineteenth Century Drama, 1800-1850, 2 vols. Cambridge UP, 1930.

“October 1811, trial of PAUL WHITEHEAD.” t18111030-44. Old Bailey Proceedings Online Version 8.0. Accessed 19 Feb. 2020.

“Paul Whitehead.” Life Archive ID obpt18111030-44-defend374. The Digital Panopticon Version 1.2. Accessed 19 Feb. 2020.

Radford, Jean. “Modernist Melancholy: Edith Sitwell’s Black Sun.” At Home and Abroad in the Empire: British Women Write the 1930s, edited by Robin Hackett, Freda Hauser, Gay Wachman, University of Delaware Press, 2009, pp. 203-221.

Reider, William D. The New Tablet of Memory; or, Recorder of Remarkable Events, Alphabetically Arranged from the Earliest Period to the Present Time. John Clements, 1841.

Ross, Charles Henry. Behind a Brass Knocker: Some Grim Realities in Picture and Prose. Chatto and Windus, 1883.

Rymer, James Malcolm. Family Secrets, or, A Page from Life’s Volume. Edward Lloyd, 1846.

——— . The Lady in Black, or, the Widow and the Wife. Edward Lloyd, 1847-8.

Sitwell, Edith. English Eccentrics. Pallas Athene, 2006.

Streetology of London, or, the Metropolitan Papers of the Itinerant Club, Being a Graphic Description of Extraordinary Individuals who Exercise Professions or Callings in the Streets of the Great Metropolis. James S. Hodson, 1837. Google Books.

“Trial of Thomas Rymer, May 1838”. t18380514-1173. Old Bailey Proceedings Online Version 8.0. Accessed 23 May 2018.

Wilson, Henry. Wonderful Characters: Memoirs and Anecdotes of Remarkable Persons, 3 vols. J. Robins, 1821-2.

Wilson, Henry, and James Caulfield. The Book of Wonderful Characters: Memoirs and Anecdotes of Remarkable and Eccentric Persons, in All Ages and Countries. Hotten, 1869. Archive.org. Accessed 23 May 2018.

Wilson, John Henry. Wonderful Characters, Comprising Memoirs and Anecdotes of Remarkable and Eccentric Persons, of Every Age and Nation. J. Barr, 1842. Accessed 23 May 2018.

“Union-Hall”. The Times, 22 Feb. 1828, p. 4.

ENDNOTES

[1] This article is an expansion of my essay “The Bank Nun’s Tale: Financial Forgery, Gothic Imagery, and Economic Power.” Victorian Network, vol. 8, 2018, pp. 28-47. Material from this essay is used with permission, for which I thank the editors of Victorian Network.

[2] Earlier editions of The Book of Wonderfull Characters contain no Bank Nun story: see, for instance, the 1821 and 1842 editions.