Katherine D. Harris, “The Legacy of Rudolph Ackermann and Nineteenth-Century British Literary Annuals”

By November 1822, the British reading public had already voraciously consumed both Walter Scott’s expensive novels and Rudolf Ackermann’s exquisite lithographs. The next decade, referred to by some scholars as dormant and unproductive, is in fact bursting with Forget Me Nots, Friendship’s Offerings, Keepsakes, and Literary Souvenirs. By wrapping literature, poetry, and art into an alluring package, editors and publishers saturated the market with a new, popular, and best-selling genre, the literary annual. In this excerpt from the introduction to Forget Me Not: The Rise of the British Literary Annual, the foundations of the literary annual, its Poetess Tradition, its varied and sometimes canonical authors are introduced in conjunction with the formative print culture and history of early nineteenth-century Britain.

Michelle Allen-Emerson, “On Magazine Day”

Magazine Day refers to the last day of every month when wholesale booksellers in London received the new monthly serial publications and prepared them for distribution. The monthly event determined the rhythm of the publishing industry for much of the nineteenth century and thus reflects the growing importance of serials to the nineteenth-century book trade.

Anna Maria Jones, “On the Publication of Dark Blue, 1871-73″

Dark Blue (1871–73) was a monthly magazine, edited by Oxford undergraduate John Christian Freund, which folded two years after a brilliant debut. During its brief run, it brought together a stunning list of literary and artistic contributors, including Dante Gabriel Rossetti, A. C. Swinburne, William Morris, Andrew Lang, Mathilde Blind, Sheridan Le Fanu, Simeon Solomon, and Ford Madox Brown, who produced aesthetically and sexually daring poetry, art, and criticism. However, it also strove to “appeal to the whole English-speaking public,” as Freund put it, and, thus, included much that might be described as middlebrow, even conservative. Whereas individual texts from Dark Blue, such as Le Fanu’s Carmilla, have received considerable attention, scholars have devoted very little sustained attention to the journal beyond noting its importance as an “artifact” in the history of the Pre-Raphaelite Movement and British aestheticism, and registering puzzlement at the journal’s eclecticism. This essay returns to Dark Blue to uncover common threads among dissimilar writers and artists. With particular attention to the journal’s commitments to transnationalism, I trace three intertwined threads—synesthesia, translation, and sexual dissidence—as they manifest in key texts by Swinburne, Solomon, Le Fanu, and others. Reading these texts in their original context not only demonstrates Dark Blue’s importance to early formations of aestheticism but also helps us to see how aestheticism connects with, rather than stands in opposition to, mid-Victorian culture.

Meaghan Clarke, “1894: The Year of the New Woman Art Critic”

In 1894, satirical journals such as Punch mockingly identified the phenomenon of the New Woman, as found in novels, plays and articles, as an intellectual and independent figure. These mannish representations of professional women seem impossible to reconcile with the aesthetic and fashionable realms of late Victorian art and culture. Studies have frequently considered the role of Victorian women as models or sitters—objects of a male artist’s inspiration. However, other career paths for women were possible. Many women were successful artists and an alternative entrée into the art world was journalism. This article will posit that women art journalists provided a living example of professional opportunities for intellectual New Women. Although their work has been largely left out of accounts of the period, they contributed to key developments in art history at the end of the century. To begin with, I will touch on the history of art writing and its development as a professional avenue for women. Then, I will explore specific themes in order to consider the diversity of their critical responses to contemporary British art circa 1894. This will encompass women’s writings on Pre-Raphaelite and academic artists as “celebrities,” groups influenced by French Impressionism in Newlyn and St. Ives, London Impressionists and Glasgow Boys, as well as art and culture beyond Britain.

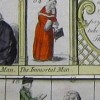

Christopher Rovee, “The New Game of Human Life, 1790″

The appearance of The New Game of Human Life on 14 July 1790 was a significant milestone in the history of British leisure. Its London publishers, John Wallis and Elizabeth Newbery, appealingly packaged the table-game for a flourishing children’s market and for middle-class consumers invested in stories of individual development and social mobility. The popularity of this race-game helped pave the way, in the decades to come, for innumerable, similarly conceived entrants in the competitive marketplace for domestic amusements—including an iconic successor, published in 1860 by a young American entrepreneur named Milton Bradley: “The Checkered Game of Life,” later “The Game of Life” and, finally, simply “Life.”

T. J. Tallie, “On Zulu King Cetshwayo kaMpande’s Visit to London, August 1882”

In August of 1882, the deposed Zulu monarch Cetshwayo kaMpande arrived in London to plead for the restoration of his kingdom, from which he had been deposed following the Anglo-Zulu War of 1879. Despite the ferocity of the war, particularly after Britain’s humiliating defeat at the Battle of Isandhlwana in January 1879, the newly elected Gladstone government sought to repudiate larger imperial goals and reversed their decision, approving Cetshwayo’s restoration. This article focuses on the depictions of Cetshwayo in the metropolitan press during his momentous 1882 visit.

Nancy Rose Marshall, “On William Powell Frith’s Railway Station, April 1862″

William Powell Frith’s oil painting, The Railway Station (1862), is an enlightening case study of the pressures and conditions that formed an art viewer in the second half of the nineteenth century in London. A painting of a contemporary urban crowd, displayed for that same crowd in a novel single-picture exhibition, has much to tell us about the emergence of modern structures of seeing and living based on new configurations of money, time, and space.

Jane Stabler, “Religious Liberty in the ‘Liberal,’ 1822-23”

A survey of the negative twentieth- and twenty-first-century critical reception of the Liberal; a summary of the history of the journal and a re-evaluation of the philosophical and political coherence of the journal, focusing on its defence of religious liberty and suggesting that religious free thought is a previously overlooked component in the politics of liberalism. The criticism of doctrinal rigidity and advocacy of different forms of religious toleration evident in the four issues of the Liberal support the claim that the journal forms a lucid and intelligible cultural intervention.

Anna Kornbluh, “Thomas Hardy’s ‘End of Prose,’ 1896”

This entry considers Thomas Hardy’s “End of Prose,” his renunciation of the novel in favor of poetry, as an important event in nineteenth-century literary history, motivated by aesthetic concerns. It reads the geometric imagery in Hardy’s final novel, Jude the Obscure, in connection with the advent of non-Euclidean geometry, suggesting that mathematical forms inspired Hardy’s turn to the poetic line.

Julie Codell, “On the Grosvenor Gallery, 1877-90”

The Grosvenor Gallery (1877-90), founded by Sir Coutts Lindsay and Lady Caroline Blanche Elizabeth Fitzroy (a Rothschild on her mother’s side) on 135-37 New Bond Street in London, generated a seismic change in the conventional Victorian art world in its exhibition of then avant-garde artists like Edward Burne-Jones, James McNeill Whistler and G. F Watts, and other leading members of the Aesthetic Movement, such as Frederic Leighton. Its unique methods of display, invitations to exhibit, support of women artists, and stunning building and interior decoration marked its ties to the Aesthetic Movement and its challenge to the Royal Academy.