Abstract

In 1894, satirical journals such as Punch mockingly identified the phenomenon of the New Woman, as found in novels, plays and articles, as an intellectual and independent figure. These mannish representations of professional women seem impossible to reconcile with the aesthetic and fashionable realms of late Victorian art and culture. Studies have frequently considered the role of Victorian women as models or sitters—objects of a male artist’s inspiration. However, other career paths for women were possible. Many women were successful artists and an alternative entrée into the art world was journalism. This article will posit that women art journalists provided a living example of professional opportunities for intellectual New Women. Although their work has been largely left out of accounts of the period, they contributed to key developments in art history at the end of the century. To begin with, I will touch on the history of art writing and its development as a professional avenue for women. Then, I will explore specific themes in order to consider the diversity of their critical responses to contemporary British art circa 1894. This will encompass women’s writings on Pre-Raphaelite and academic artists as “celebrities,” groups influenced by French Impressionism in Newlyn and St. Ives, London Impressionists and Glasgow Boys, as well as art and culture beyond Britain.

Art Writing as a Profession

By the last decades of the nineteenth century, there was already a strong precedent for women writing art criticism in Britain. Several women were writing about art at the beginning of the Victorian period. Mariana Starke’s travel guides had pre-dated John Murray and Anna Jameson’s writings for the Penny Magazine had pre-dated John Ruskin and Jameson’s work on collections and iconography; such work continued to be referenced throughout the century by art scholars, as well as the wider public. Translation and gallery guides were also critical for these early writers. For example, the writer Mary Merrifield’s first published work in 1844 was a translation of Cennino Cennini’s 1437 treatise on painting, while the artist and writer Kate Thompson in 1877 combined a guide to major European Galleries with an introduction to art historical schools. It is hardly surprising that, with the explosion in the periodical press in the 1880s, women contributed to ever more publications. These included journals associated with the New Journalism for the masses, such as the Star and Pall Mall Gazette, the general-interest Illustrated London News, and specialist presses such as the Art Journal and Magazine of Art. The other crucial development in art writing was that illustrations accompanied essays and articles. By the 1890s, readers could not only envision London exhibitions through the press, but the accompanying full-page prints could be framed to envision the latest in fashionable domestic interiors.

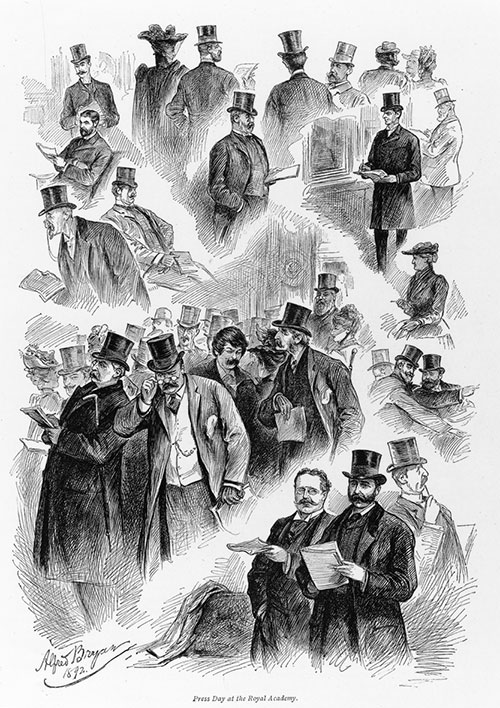

This period also coincided with fundamental shifts in professionalization for women, including the establishment of professional societies such as the Society of Women Journalists and the Women Authors Club, both of which included women art writers as members. Through their attendance at private views and exhibition openings, women were regularly visible in the art world. An article published in 1892 entitled “Art Critics of Today,” named numerous critics who wrote for daily and weekly newspapers and the art press, and the list included several women.

The illustration that accompanied the article included portraits of women art critics, all of them fashionably attired, gliding around a gallery in groups or singly, clutching in their hands the crucial accessory for all critics: the catalogue (Aliquis; Clarke, Critical Voices, 1-9).

Artist Celebrities

The art press specifically cultivated a late Victorian fascination with biography. The “life and letters” format appeared in article series and also as luxuriously illustrated Art Annuals for the Art Journal. Like the great tomes of the period, these were often hagiographic, and crucial for building the artists’ reputations since they carried extensive reproductions of artists’ works. The celebrity status of artists and their personality cults grew as portraits, photographs and “peeps” into artist’s studios were revealed to a reading public (Codell 45-71). Many women writers highlighted the professional and financial status of Royal Academicians, many of whom were living in palatial studios in the leafy suburbs of ![]() Leighton House and

Leighton House and ![]() Holland Park (Campbell; Dakers).

Holland Park (Campbell; Dakers).

The art writer and poet, Alice Meynell, was responsible for the 1893 volume on the Pre-Raphaelite artist, William Holman Hunt, along with Archdeacon Farrar. Farrar provided the religious interpretation of Hunt’s work while Meynell provided the “studio” biography. By this point, Hunt himself was concerned with the reputation of the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood. Specifically, he wanted to emphasize that his painting as opposed to that of Dante Gabriel Rossetti had retained the Brotherhood’s original principles. In the Art Annual, Meynell gave credence to Hunt’s Pre-Raphaelite pre-eminence by presenting the longevity of his oeuvre (1848-1893). She did so by including a somewhat bizarre re-enactment photograph of Hunt in his garden, at his easel, painting the Scapegoat in the Holy Land, a work he had completed forty years earlier. See Fig. 2.

Meynell’s volume thus placed Hunt on the same level as the Royal Academicians who had featured in Art Annuals. Moreover, her status as a renowned art writer lent critical authority to a Hunt-centred account of Pre-Raphaelitism in opposition to the writings on the history of the PRB by Rossetti’s brother, William Michael Rossetti, and others.[1]

Similarly, Julia Cartwright became an important supporter of the artist Edward Burne-Jones towards the end of his career, actively positioning him in the Art Journal‘s series of “great artists” and thus consolidating his career as a “new” old master (Ady). Burne-Jones, like Hunt, was associated with Pre-Raphaelitism, and remained largely peripheral to the Royal Academy. Burne-Jones exhibited at the Grosvenor Gallery (the home of Aestheticism), the New Gallery and in Europe. (On the Grosvenor Gallery, see Julie Codell, “On the Grosvener Gallery, 1877-90.″) In addition to the Art Annual published for Christmas 1894, Cartwright wrote several articles on Burne-Jones and her personal correspondence with the artist attests to his preoccupation with having an advocate for his work in the press (164-166). She had access to the artist’s working studio and his careful consideration of illustrations for her articles emphasized the value of art journalism for artists. An Art Journal article coincided with his 1893 solo exhibition at the New Gallery and in 1896 she compiled the catalogue for an exhibition of his drawings at the ![]() Fine Art Society. Burne-Jones had resigned from the Academy in 1893, and was therefore located outside it. This made him especially intent on cultivating a good rapport with Cartwright. He benefited from having a confidante in the press who was willing to explicate the mysterious symbolism of his work.

Fine Art Society. Burne-Jones had resigned from the Academy in 1893, and was therefore located outside it. This made him especially intent on cultivating a good rapport with Cartwright. He benefited from having a confidante in the press who was willing to explicate the mysterious symbolism of his work.

The battle artist Elizabeth Thompson Butler was extraordinarily fortunate to have a publicist, writing, often pseudonymously, on her behalf. Butler had narrowly missed appointment to the ![]() Royal Academy in 1877 and was one of the many later Victorian artists who were regularly cited as “great women” in arguments favouring female suffrage. Butler’s correspondence with her sister, Meynell, indicates their reciprocal attention to exhibitions and art world events. Moreover, by the 1890s Meynell occupied an elite status within Victorian literary circles and shared her sister’s unease with British imperial policies. Butler had travelled to

Royal Academy in 1877 and was one of the many later Victorian artists who were regularly cited as “great women” in arguments favouring female suffrage. Butler’s correspondence with her sister, Meynell, indicates their reciprocal attention to exhibitions and art world events. Moreover, by the 1890s Meynell occupied an elite status within Victorian literary circles and shared her sister’s unease with British imperial policies. Butler had travelled to ![]() Egypt and

Egypt and ![]() South Africa with her husband General William Butler. Meynell’s emphasis on the humanity in her sister’s work revealed the anti-imperialist viewpoints of their liberal Catholic family circle (Usherwood and Spencer-Smith 79-84). Butler’s reputation warranted her appearance in an Art Annual in 1898, which was authored by none other than Meynell’s husband Wilfrid, who was also a journalist. Meynell wrote a number of provocative works about the roles of women and went on to become very involved in the suffrage movement.

South Africa with her husband General William Butler. Meynell’s emphasis on the humanity in her sister’s work revealed the anti-imperialist viewpoints of their liberal Catholic family circle (Usherwood and Spencer-Smith 79-84). Butler’s reputation warranted her appearance in an Art Annual in 1898, which was authored by none other than Meynell’s husband Wilfrid, who was also a journalist. Meynell wrote a number of provocative works about the roles of women and went on to become very involved in the suffrage movement.

Another woman who became tremendously vocal in pen and platform was the journalist Florence Fenwick-Miller. Trained in medicine and an early member of the London School Board, Fenwick-Miller had shifted to journalism, writing a regular ladies’ column for the Illustrated London News. She was a tireless campaigner for women’s rights and gave extensive coverage to women artists. Throughout the Victorian period, women were entirely absent from membership of the British Royal Academy, despite the two female founding members Angelica Kauffman and Mary Moser. Fenwick-Miller made repeated calls for the election of women artists like Elizabeth Butler, Henrietta Rae and Louise Jopling as members (Fenwick-Miller, “The Ladies’ Column” 478).

For Fenwick-Miller, the portrait artist Jopling epitomised beauty and fashionability. Jopling’s appearances at exhibition openings and her studio open houses were regularly highlighted in Fenwick-Miller’s column. More recently scholars have documented the public function of artists’ studios during this period, especially for Show Sunday, an important day in the social calendar preceding the spring exhibition, wherein carriages would be lined up around the block outside the home of Frederic Leighton, President of the Royal Academy (Dakers 2-4). For women artists such as Jopling, Studio Sunday was equally crucial. Contrary to received accounts of middle-class domestic interiors becoming increasingly private and segregated in the late-Victorian and Edwardian period, these spaces hosted multiple public functions (Walker 182; Hamlett 45-50). Jopling’s studio functioned as a space for work, publicity and entertaining, and by the 1890s it had an added function as a meeting place for suffrage mobilization. Like Fenwick-Miller, Jopling was a keen suffragist who successfully campaigned for equal rights for women members of the Society of Portrait Painters.

In the Art Journal, Fenwick-Miller contributed “Art in the Woman’s Section of the ![]() Chicago Exhibition,” a review of the Columbian Exhibition of 1893, where the murals of Mary Cassatt, Annie Swynnerton and Anna Lea Merritt could be seen. But Fenwick-Miller also addressed the drawbacks of gender segregation in “women-only” exhibitions. Nonetheless, her egalitarian feminist position shifted when the artist Henrietta Rae organised the women’s Victorian Era exhibition at

Chicago Exhibition,” a review of the Columbian Exhibition of 1893, where the murals of Mary Cassatt, Annie Swynnerton and Anna Lea Merritt could be seen. But Fenwick-Miller also addressed the drawbacks of gender segregation in “women-only” exhibitions. Nonetheless, her egalitarian feminist position shifted when the artist Henrietta Rae organised the women’s Victorian Era exhibition at ![]() Earl’s Court in 1897. Here she claimed that for the first time a “genuine display was available that showed the best work by the best women artists” (Fenwick-Miller, “Women’s Pictures at the Victorian Exhibition, Earl’s Court: Interview with Henrietta Rae” 19-20). Her interview with Rae highlighted the latter’s affiliation with Royal Academy circles and the artist’s proclivity for painting expansive nudes in a neo-classical style, on a par with the President of the Royal Academy Frederic Leighton.

Earl’s Court in 1897. Here she claimed that for the first time a “genuine display was available that showed the best work by the best women artists” (Fenwick-Miller, “Women’s Pictures at the Victorian Exhibition, Earl’s Court: Interview with Henrietta Rae” 19-20). Her interview with Rae highlighted the latter’s affiliation with Royal Academy circles and the artist’s proclivity for painting expansive nudes in a neo-classical style, on a par with the President of the Royal Academy Frederic Leighton.

Impressionism: ![]() Newlyn, London and Glasgow

Newlyn, London and Glasgow

Although Meynell was certainly a firm supporter of her sister, an academic artist, she also wrote two early articles—“A Brighton Treasure-House” and “Pictures from the Hill Collection”—on the Brighton collector of French impressionist works, Captain Henry Hill. Hill’s collection included British landscape artists, but also works by Monet and Degas. In 1889, Meynell turned her attention to a new group of artists influenced by this work.

The “Newlyn” artists—Stanhope Forbes, Elizabeth Amstrong, Walter Langley, Adrian Stokes and Marianne Preindlsburger Stokes—had retreated to ![]() Cornwall, in order to escape London and paint en plein air by the sea. Meynell is credited with giving the label, the “Newlyn School” to the group, who although quite diverse, were united in their experience of studying in

Cornwall, in order to escape London and paint en plein air by the sea. Meynell is credited with giving the label, the “Newlyn School” to the group, who although quite diverse, were united in their experience of studying in ![]() France. Their style of painting was not academic, and they initially exhibited as part of the New English Art Club. Not only did these artists deploy new methods of painting out of doors, but they also used a “square brush” technique, instead of elaborate under-drawing and studio work. Meynell’s article series on “Newlyn” brought the group to the attention of Art Journal readers. She continued her support of the group in the 1890s as some of their members gained acceptance in the Royal Academy.

France. Their style of painting was not academic, and they initially exhibited as part of the New English Art Club. Not only did these artists deploy new methods of painting out of doors, but they also used a “square brush” technique, instead of elaborate under-drawing and studio work. Meynell’s article series on “Newlyn” brought the group to the attention of Art Journal readers. She continued her support of the group in the 1890s as some of their members gained acceptance in the Royal Academy.

Another artist associated with modern French painting, John Singer Sargent, also benefited from Meynell’s support. She was among the critics who acclaimed his painting Carnation, Lily, Lily Rose when it was purchased for the British nation in 1887. This was a moment of change in the expectations of British critics and the academy that was to be pivotal in the history of British modernism (Helmreich, 434). Meynell continued to promote his work and the significance of her role as a critic is attested to in a portrait he did of her in 1894 (![]() National Portrait Gallery, London). In the elongated pencil sketch, Meynell stands in a loosely draped “Aesthetic” dress, eschewing tight corseting, with a high collar and fashionable leg-of-mutton sleeves. Her hands are clasped while her dark eyes return the gaze of the viewer. The placement of the picture on the wall of Meynell’s home signalled to visitors the importance of the artist-critic relationship. Their collaboration culminated in a 1903 luxury portfolio of reproductions of Sargent’s portraits of other artists, writers and celebrities. Meynell wrote the accompanying essay and her portrait was among those included; it was further reproduced to accompany collections of her own work, The Work of John S. Sargent, R.A.). See Fig. 3.

National Portrait Gallery, London). In the elongated pencil sketch, Meynell stands in a loosely draped “Aesthetic” dress, eschewing tight corseting, with a high collar and fashionable leg-of-mutton sleeves. Her hands are clasped while her dark eyes return the gaze of the viewer. The placement of the picture on the wall of Meynell’s home signalled to visitors the importance of the artist-critic relationship. Their collaboration culminated in a 1903 luxury portfolio of reproductions of Sargent’s portraits of other artists, writers and celebrities. Meynell wrote the accompanying essay and her portrait was among those included; it was further reproduced to accompany collections of her own work, The Work of John S. Sargent, R.A.). See Fig. 3.

Figure 3: John Singer Sargent, sketch of Alice Meynell (née Thompson), 1894 (pencil, 14 1/4 in. x 8 1/4 in., 362 mm x 210 mm, © National Portrait Gallery, London

The New English Art Club, founded in 1886, also exhibited works by two other groups of artists influenced by French methods. In the press, these “modern” methods of painting found supporters among writers who came to be known as the New Critics. Among these writers was the American, Elizabeth Robins Pennell, who became a regular art columnist for both the London Star and ![]() New York Nation, writing pseudonymously as A.U. and N.N. In both these papers, she expressed support for the London Impressionists, who included Walter Sickert, Philip Wilson Steer and Sidney Starr, and the Glasgow Boys, which included James Guthrie, John Lavery and E. A. Hornel. Moreover, she repeatedly opposed academic painting and the Royal Academy. When a dispute arose in 1893 concerning the exhibition of Degas’s L’Absinthe at the Grafton Gallery, she targeted the pseudonymous “Philistine” (J. A. Spender) who decried the moral depravity of the piece (Robins and Thomson, 208-211; Flint 3-8).

New York Nation, writing pseudonymously as A.U. and N.N. In both these papers, she expressed support for the London Impressionists, who included Walter Sickert, Philip Wilson Steer and Sidney Starr, and the Glasgow Boys, which included James Guthrie, John Lavery and E. A. Hornel. Moreover, she repeatedly opposed academic painting and the Royal Academy. When a dispute arose in 1893 concerning the exhibition of Degas’s L’Absinthe at the Grafton Gallery, she targeted the pseudonymous “Philistine” (J. A. Spender) who decried the moral depravity of the piece (Robins and Thomson, 208-211; Flint 3-8).

Robins Pennell was also affiliated with a group of ex-patriot Americans in London. Among them was the artist James McNeill Whistler. Robins Pennell wrote a laudatory piece on his 1892 exhibition at the Goupil Gallery entitled Nocturnes, Marines and Chevalet Pieces, in which she declared he was an Impressionist “before the name Impressionism had been heard” (N. N.). Just like Sargent’s portrayal of Meynell, Whistler’s lithographic portrait of Robins Pennell offers visual evidence of the significant role Pennell played as a critic for Whistler. The piece, depicting her seated in front of a fire with strongly contrasting flickering light and shadow, was included in an exhibition of Whistler’s prints at the Fine Art Society in 1895 (Fig. 4).

Figure 4: James McNeill Whistler, Firelight: Elizabeth Robins Pennell (1896, ![]() Library of Congress)

Library of Congress)

Robins Pennell continually condemned the poor showing of “black and white” or print artists at the Royal Academy and the fact that Whistler’s work was not represented in London collections. Whistler’s work had not been selected for the nation as part of the Chantrey Bequest. Whistler reciprocated this support in 1897 when Robins Pennell and her printmaker husband Joseph Pennell became embroiled in a libel case against the artist Walter Sickert (Clarke, “Seeing in Black-and-White” 581-587). Robins Pennell became a lifelong memorialiser of Whistler’s work; she wrote a two-volume biography, The Life of James McNeill Whistler in 1908 and put together the Whistler collection in the Library of Congress.

Beyond Britain

Robins Pennell’s writings contributed to a transatlantic assessment of modernism, but this was in part informed by her travels in Europe. Robins Pennell’s fame for travelling by bicycle made her an archetypal example of a New Woman. She published essays and volumes about her cycling adventures around Europe in the 1880s and 1890s, including most extraordinarily Over the ![]() Alps on a Bicycle in 1898 (Pennell, Over the Alps on a Bicycle). Fluent in French, she also regularly travelled back and forth to

Alps on a Bicycle in 1898 (Pennell, Over the Alps on a Bicycle). Fluent in French, she also regularly travelled back and forth to ![]() Paris during this period in order to review exhibitions. Travel was an important aspect of art criticism. First, to see art works first hand was considered the only way in which one could become an authority on art, and secondly the art world was becoming increasingly internationalised through exhibitions, the art market and the art press. Foreign correspondents became a vital aspect of art reviewing. For example, the art magazine Studio, founded in 1893, had regular correspondents, usually pseudonymous, from European centres like Berlin, Paris, Brussels, Dresden, Milan and Venice.

Paris during this period in order to review exhibitions. Travel was an important aspect of art criticism. First, to see art works first hand was considered the only way in which one could become an authority on art, and secondly the art world was becoming increasingly internationalised through exhibitions, the art market and the art press. Foreign correspondents became a vital aspect of art reviewing. For example, the art magazine Studio, founded in 1893, had regular correspondents, usually pseudonymous, from European centres like Berlin, Paris, Brussels, Dresden, Milan and Venice.

Several women art writers actually lived in Europe, demonstrating a cultural engagement with wider geographies. Helen Zimmern exemplified this transnationalism. She offered readers access to a diversity of cultures. Her multilingualism allowed her to publish in British, German and Italian presses and her writing was remarkable in its breadth. Her work on the German philosopher Arthur Schopenhauer led to a friendship with Frederic Nietzsche and she even translated his work. She also translated from French Ferdowsi’s Epic of Kings or Shahnameh, which narrates the mythical and historical reign of 50 Persian Kings. Her work was an adaptation into early modern English illustrated by the Royal Academician Laurens Alma Tadema. In her introduction to the epic, Zimmern on the one hand amplified an imperial political context, citing Britain as the greatest European power in the East. On the other hand, she presented a cultural encounter aimed at resuscitation, emphasizing the importance of the “beauties” of Persian literary heritage, as counterparts to Homer’s Iliad and Odyssey. |

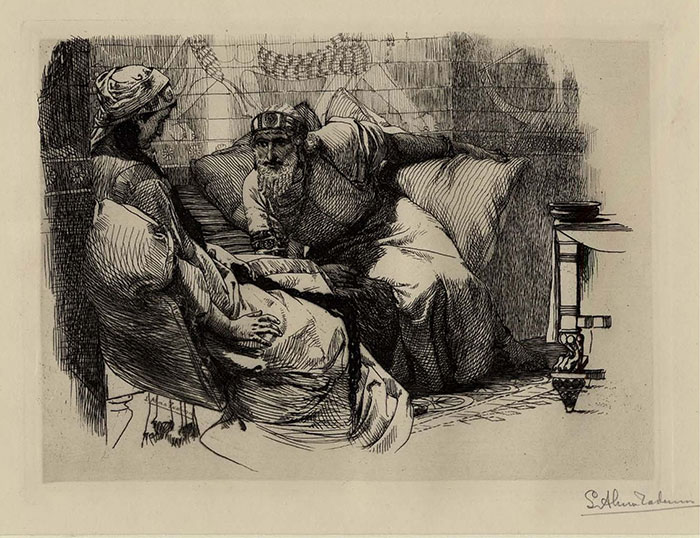

For the project, Alma Tadema made an unusual shift from his customary ancient Roman subject matter in the accompanying etching of the meeting of Zal and Rudabeh in ![]() Kabul (Fig. 5).

Kabul (Fig. 5).

Figure 5: Alma Tadema, Zal and Rudabeh, etching, 1882 (148 mm x 203 mm, © Trustees of the ![]() British Museum)

British Museum)

The Orientalised Babylonian interpretation of the epic was adapted from an Assyrian scene of King Ashurbanipal and his wife from Nineveh (c. 645 BCE, British Museum). The furniture also bears similarities to the Persian-style divan depicted in his daughter Anna Alma Tadema’s watercolour of the family drawing room (Calloway, Orr, and Whittaker 9; R. J. Barrow 91).[1] A Victorian copy of an Assyrian relief and Zimmern’s seemingly contradictory interpretation conjoin to reveal the complicated nature of cultural exchange during this period (MacLeod 3–4; Codell, Transculturation in British Art, 1770-1930 1-17). Whilst tensions continued to emerge between cultural and political agendas in the Near East (Malley 3), Zimmern reflected a mounting concern for the preservation of global heritage.

Her endeavour to popularise the epic for an English readership was successful with subsequent cheaper editions in the 1880s and 1890s. This early collaboration was equally propitious for Alma Tadema: Zimmern became his chief biographer, publishing articles, an Art Annual and a later monograph on the artist, Sir Lawrence Alma Tadema, R. A. ![]() However, her interests were not limited to Royal Academicians. Resident in Florence by the 1890s, Zimmern wrote extensively on contemporary Italian artists, and was an early promoter of the most avant-garde work by the Italian painter, Giovanni Segantini. Zimmern offered a challenging analysis of Segantini’s new symbolist paintings for Magazine of Art readers (Zimmern, “Giovanni Segantini” 31; Clarke, “Critical Mediators” 232-233). Her prolific career indicates the importance of women as translators and cultural mediators by 1894, introducing both British and European readers to artists and cultures outside their immediate purview.

However, her interests were not limited to Royal Academicians. Resident in Florence by the 1890s, Zimmern wrote extensively on contemporary Italian artists, and was an early promoter of the most avant-garde work by the Italian painter, Giovanni Segantini. Zimmern offered a challenging analysis of Segantini’s new symbolist paintings for Magazine of Art readers (Zimmern, “Giovanni Segantini” 31; Clarke, “Critical Mediators” 232-233). Her prolific career indicates the importance of women as translators and cultural mediators by 1894, introducing both British and European readers to artists and cultures outside their immediate purview.

Conclusion

In conclusion, the 1890s were an extremely productive period for women art critics. They achieved substantial professional recognition through new organisations and in their dealings with artists, editors and publishers. It was economically viable to pursue art writing as a profession; work as newspaper columnists guaranteed a regular income for Meynell, Fenwick- Miller and Robins Pennell. Allegiances with specific artists led to the production of additional artist biographies in the form of articles and volumes, it also indicated the weight of their authority in the art world. In 1894, women art writers offered a multiplicity of voices: some wrote histories of Pre-Raphaelitism and Royal Academicians, while others intently worked towards an increased recognition of women artists such as Elizabeth Thomson Butler, Henrietta Rae and Louise Jopling. Moreover, critics such as Meynell and Robins Pennell became crucial advocates of groups—like the Newlyn School and Glasgow Boys—associated with modern art in Britain, as well as individual artists such as Sargent and Whistler. As cross-channel travel became available to many more people, the market expanded for wider geographical expertise in art criticism. Experience of travel and translation was invaluable for art writers; many women capitalised on this development. By acting as cultural intermediaries from Europe and beyond, women such as Zimmern articulated a growing internationalism in the art press. Although not necessarily adhering to the stereotype of the New Woman evident in the pages of Punch in 1894, women art writers made crucial interventions in the contemporary art world.

published May 2015

HOW TO CITE THIS BRANCH ENTRY (MLA format)

Clarke, Meaghan. “1894: The Year of the New Woman Art Critic.” BRANCH: Britain, Representation and Nineteenth-Century History. Ed. Dino Franco Felluga. Extension of Romanticism and Victorianism on the Net. Web. [Here, add your last date of access to BRANCH].

WORKS CITED

Ady, Julia Mary Cartwright. The Life and Work of Sir Edward Burne-Jones. London: Art Journal, 1894. Print.

Aliquis. “Art Critics of to-Day.” Art Journal, 1839-1912 (1892): 193–197. Print.

Calloway, Stephen, Lynn Federle Orr, and Esmé Whittaker, eds. The Cult of Beauty: The Aesthetic Movement 1860-1900. London: V&A Publishing, 2011. Print.

Campbell, Louise. “Decoration, Display, Disguise: Leighton House Reconsidered.” Frederic Leighton: Antiquity, Renaissance, Modernity. Ed. Elizabeth Prettejohn and T. J. Barringer. New Haven: Published for the Paul Mellon Centre for Studies in British Art [and] the Yale Center for British Art [by] Yale UP, 1999. 267–293. Print.

Cartwright, Julia. A Bright Remembrance: The Diaries of Julia Cartwright, 1851-1924. London: Weidenfeld and Nicolson, 1989. Print.

Cherry, Deborah. Beyond the Frame: Feminism and Visual Culture, Britain, 1850-1900. London: Routledge, 2000. Print.

—. Painting Women: Victorian Women Artists. London: Routledge, 1993. Print.

Clarke, Meaghan. “Critical Mediators: Locating the Art Press.” Visual Resources 26.3 (2010): 226–241. Print.

—. Critical Voices: Women and Art Criticism in Britain, 1880-1905. Aldershot: Ashgate, 2005. Print.

—. “Seeing in Black-and-White: Incidents in Print Culture.” Art History 35.3 (2012): 574–595. Print.

Codell, Julie F. The Victorian Artist: Artists’ Lifewritings in Britain, Ca. 1870-1910. Cambridge: Cambridge UP, 2003. Print.

—, ed. Transculturation in British Art, 1770-1930. Farnham, Surrey, England; Burlington, Vt: Ashgate, 2012. Print.

Dakers, Caroline. The Holland Park Circle: Artists and Victorian Society. London: Yale UP, 1999. Print.

Farrar, F. W., and Alice Meynell. William Holman Hunt: His Life and Work. Sl: Art journal office, 1893. Print.

Fenwick-Miller, Florence. “Art in the Woman’s Section of the Chicago Exhibition.” Art Journal (December 1893): 13–16. Print.

—. “The Ladies’ Column.” Illustrated London News 13 Oct. 1894: 478. Print.

—. “Women’s Pictures at the Victorian Exhibition, Earl’s Court: Interview with Henrietta Rae.” Woman’s Signal (1897): 19–20. Print.

Flint, Kate. “The ‘Philistine’ and the New Art Critic: J. A. Spender and D. S. Maccoll’s Debate of 1893.” Victorian Periodicals Review 21.1 (1988): 3–8. Print.

Gardner, Vivien, and Susan Rutherford, eds. The New Woman and Her Sisters: Feminism and Theatre, 1850-1914. New York; London: Harvester Wheatsheaf, 1992. Print.

Hamlett, Jane. Material Relations: Domestic Interiors and Middle-Class Families in England, 1850-1910. Manchester: Manchester UP, 2010. Print.

Helmreich, Anne. “John Singer Sargent, Carnation, Lily, Lily, Rose, and the Condition of Modernism in England, 1887.” Victorian Studies 45.3 (2003): 433–455. Print.

Ledger, Sally. The New Woman: Fiction and Feminism at the Fin de Siècle. Manchester: Manchester UP, 1997. Print.

MacLeod, Dianne Sachko. “Introduction: Women’s Artistic Passages.” Intrepid Women: Victorian Artists Travel. Ed. Jordana Pomeroy. Aldershot: Ashgate, 2005. 1–10. Print.

Malley, Shawn. From Archaeology to Spectacle in Victorian Britain: The Case of Assyria, 1845-1854. Farnham: Ashgate, 2012. Print.

Meynell, Alice. “A Brighton Treasure-House.” Ed. Marion Harry Spielmann. The Magazine of Art 5 (1882): 1–7. Print.

—. “Newlyn.” Art Journal, 1839-1912 (1889): 97–102. Print.

—. “Newlyn.” Art journal, 1839-1912 (1889): 137–142. Print.

—. The Work of John S. Sargent, R. A. London: William Heinemann, 1903. Print.

N. N., (Pennell). “Mr. Whistler’s Triumph.” Nation (April 1892): 280–1. Print.

Nunn, Pamela Gerrish. Victorian Women Artists / Pamela Gerrish Nunn. London: Women’s, 1987. Print.

Pennell, Elizabeth Robins. Over the Alps on a Bicycle. London: T. F. Unwin, 1898. Print.

—. The Life of James McNeill Whistler. London: William Heinemann, 1908.

R. J. Barrow, (Rosemary J.). Lawrence Alma-Tadema. London: Phaidon, 2001. Print.

Robins, Anna Gruetzner and Richard Thomson. Degas, Sickert and Toulouse-Lautrec: London and Paris, 1870-1910. London: Tate, 2005. Print.

Thompson, Kate. A Handbook to the Public Picture Galleries of Europe. With a Brief Sketch of the History of the Various Schools of Painting, from the 13th Century to the 18th Inclusive. London, 1877. Print.

Usherwood, Paul and Jenny Spencer-Smith. Lady Butler, Battle Artist, 1846-1933. Gloucester: Sutton, 1987. Print.

Walker, Lynne. “Locating the Global/Rethinking the Local: Suffrage Politics, Architecture, and Space.” Women’s Studies Quarterly 34.1/2 (2006): 174–196. Print.

Willis, Chris and Angelique Richardson, eds. The New Woman in Fiction and in Fact: Fin-de-Siècle Feminisms. Basingstoke: Palgrave in association with Institute for English Studies, School of Advanced Study, University of London, 2000. Print.

Zimmern, Helen. “Giovanni Segantini.” Magazine of Art (1896): 25–31. Print.

—. L. Alma Tadema: His Life and Work. Art Journal (1886). Print.

—. Sir Lawrence Alma Tadema, R.A. London: G. Bell and Sons, 1902. Print.

—. The Epic of Kings: Stories Retold from Firdusi. London, Edinburgh: T Fisher Unwin, 1882. Print

Further Reading

Clarke, Meaghan. “(Re)viewing Whistler and Sargent: Portraiture at the Fin-de-Siècle.” RACAR – Canadian Art Review 30.1-2 (2005): 74–86. Print.

—. “Critical Mediators: Locating the Art Press.” Visual Resources 26.3 (2010): 226–241. Print.

—. Critical Voices: Women and Art Criticism in Britain, 1880-1905. Aldershot: Ashgate, 2005. Print.

—. “Seeing in Black-and-White: Incidents in Print Culture.” Art History 35.3 (2012): 574–595. Print.

Eastlake, Elizabeth. The Letters of Elizabeth Rigby, Lady Eastlake. Ed. Julie Sheldon. Liverpool: Liverpool UP, 2009. Print.

Fraser, Hilary. Women Writing Art History in the Nineteenth Century: Looking like a Woman. Cambridge: Cambridge UP, 2014. Print.

Jameson, Anna. Diary of an Ennuyée. London: Henry Colburn, 1826. Print.

Johnston, Judith. Anna Jameson: Victorian, Feminist, Woman of Letters. Aldershot: Scolar, 1997. Print.

Kanwit, John Paul M. Victorian Art Criticism and the Woman Writer. Columbus: Ohio State UP, 2013. Print.

McConkey, Kenneth. Impressionism in Britain. New Haven: Yale UP in association with Barbican Art Gallery, 1995. Print.

—. The New English: A History of the New English Art Club. London: Royal Academy of Arts, 2006. Print.

Robins, Anna Gruetzner. A Fragile Modernism: Whistler and His Impressionist Followers. New Haven, Conn; London: Yale UP, 2007. Print.

Schaffer, Talia. The Forgotten Female Aesthetes: Literary Culture in Late-Victorian England. Charlottesville: UP of Virginia, 2000. Print.

Sherman, Claire Richter and Adele M Holcomb, eds. Women as Interpreters of the Visual Arts, 1820-1979. Westport; London: Greenwood Press, 1981. Print.