Abstract

The first public exhibition of war photographs opened in London in late September 1855, during the costly and controversial Crimean War. The show introduced over 300 black and white images taken by well-known photographer Roger Fenton (1819-1869) and continued with various additions over the next several months in Britain. Later host cities included Manchester, Birmingham, and Belfast. Queen Victoria and Prince Albert were the leading sponsors of the shows. The first exhibition was well chronicled at the time, and this essay reviews some of those public contemporary responses, published primarily in major newspapers and periodicals, as well as in photographic society journals. Those responses are considered in light of the history of photography, mid-Victorian matters of art, science and war, and common conclusions at the time and that the show was primarily a work of propaganda to support the Crimean War and that Fenton’s images were not realistic.

1855 was hardly a year of mid-Victorian equipoise, with all due respect to W. L. Burn.[1] The Crimean War had turned but was not yet over. London’s streets and pubs echoed with heated public conversations about supplies, casualties, and command, seemingly converging in a perfect storm at the official Commission of Inquiry. The same could be said of ![]() Manchester and

Manchester and ![]() Liverpool, as well as of Parliament’s chambers and the press. The Illustrated London News attacked “[t]he leading members of the Peace party, after doing all in their power to prevent the vigorous prosecution of the war,” while the commonly patriotic and loyal, if not at times loyal in opposition, London Times, on both 10 November and 23 January 1855, queried the causes of the fatal “chaos at

Liverpool, as well as of Parliament’s chambers and the press. The Illustrated London News attacked “[t]he leading members of the Peace party, after doing all in their power to prevent the vigorous prosecution of the war,” while the commonly patriotic and loyal, if not at times loyal in opposition, London Times, on both 10 November and 23 January 1855, queried the causes of the fatal “chaos at ![]() Balaklava” (547, 10). Only ten days later on 3 February, The Times expounded on the “cost” of the War (6). Among such costs was “[t]he monster waste…in the transports…a large proportion…belong[ing] to companies that have postal contracts.” The War was a logistical nightmare with resulting human, supply and animal “cost.”[2]

Balaklava” (547, 10). Only ten days later on 3 February, The Times expounded on the “cost” of the War (6). Among such costs was “[t]he monster waste…in the transports…a large proportion…belong[ing] to companies that have postal contracts.” The War was a logistical nightmare with resulting human, supply and animal “cost.”[2]

The churning waters of private correspondence were no more tranquil than the shark-infested ones of “public opinion” and the Houses of Parliament. Later that same year, “cranky” Thomas Carlyle corresponded with his brother about “that brutish Turk-War business” that was full of “chaotic imbecilities and rotten fat” (The Collected Letters of Thomas and Jane Welsh Carlyle , 27 November 1855, 121). He scribbled in a subsequent letter that he thought the “British Army in a state beyond parallel for want of command” (The Collected Letters 142). Not only were the enemy Russian officers “far superior” to their French and British counterparts, but the “British Fighting-Apparatus, at home and abroad, [is also] a mere hulk of chaotic imbecilities and rotten fat (so to speak), incapable of fighting anything!” (The Collected Letters , 15 December 1855, 142). Carlyle was hardly alone in privately expressing to family and friends what so many others were doing both in private and public.

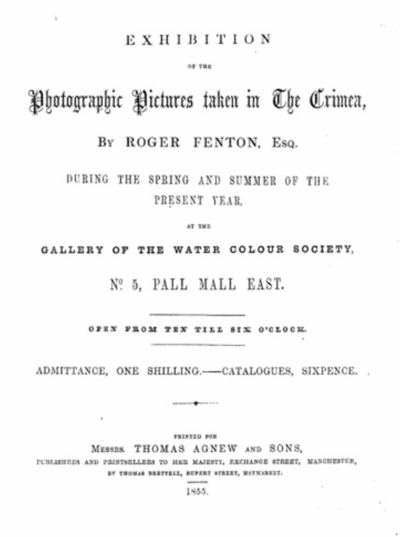

1855 was also the year of the first public exhibitions of what we now would call “war photography” or “war photojournalism.” The first of the series formally opened on 20 September at the Water Colour Society in ![]() Pall Mall,

Pall Mall, ![]() London’s East End, taking advantage of public interest in the Crimean War, the expressed patronage of Queen Victoria and Prince Albert, and curiosity about the still relatively new art or science of photography (Figure 1). There was debate at the time about to which photography belonged, art or science. Visitors observed, read about, and discussed over three hundred photographs by the well-known photographer, Roger Fenton (1819-1869) and his assistant. The title of the exhibition was “Photographic Pictures taken in The Crimea,” which was also referred to as the “Photographic Images from the Seat of War in the Crimea.” They went on public display in several venues in major British cities as the War and the above controversies continued to rage. The images included those of Carlyle’s “incapable” British commanders.

London’s East End, taking advantage of public interest in the Crimean War, the expressed patronage of Queen Victoria and Prince Albert, and curiosity about the still relatively new art or science of photography (Figure 1). There was debate at the time about to which photography belonged, art or science. Visitors observed, read about, and discussed over three hundred photographs by the well-known photographer, Roger Fenton (1819-1869) and his assistant. The title of the exhibition was “Photographic Pictures taken in The Crimea,” which was also referred to as the “Photographic Images from the Seat of War in the Crimea.” They went on public display in several venues in major British cities as the War and the above controversies continued to rage. The images included those of Carlyle’s “incapable” British commanders.

The Illustrated London News (ILN) informed its many readers that this show was “the most interesting exhibition in London at the present time” (“The Photographic Exhibition from the Seat of War” 499). The paper recommended “all who have not visited the collection to lose no time in doing so, if they would make themselves thoroughly acquainted with the excellence of photography as art, with its uses as a recorder and illustrator of the events” (“The Photographic Exhibition from the Seat of War” 499). Readers were tempted with promises of “the noble resemblance of the leading men of the Allied armies, and with a truthful representation of the historic and for ever memorable scenes” (“The Photographic Exhibition from the Seat of War” 499). This was not the immediate gratification of modern photojournalism, but there was the gratification of seeing images from “the last twelve months.” The display of Fenton’s images was a novelty: an exhibition devoted entirely to war photographs, visited while the war continued without a certain end during the early (and often uncertain) years in the history of photography. The ILN’s readers could read about Fenton, his labors in the ![]() Crimea and the images themselves over the next few months, alongside more conventional journalistic accounts and engravings of the War.

Crimea and the images themselves over the next few months, alongside more conventional journalistic accounts and engravings of the War.

The Times was no less enthusiastic, its editors noting: “[a]lthough photographic art has been already applied to an almost boundless range of subjects, it has produced nothing at all comparable in importance to the large collection of views now exhibiting” (“Photography in the Crimea” 7). They took time and space to appreciate the number and variety of the photographic images. There were “[p]ortraits not only of Generals, but of obscure persons, illustrative of the present life in the Crimea, extensive landscapes” as well (“Photography in the Crimea” 7). The inclusion of such “obscure” individuals was a reminder of photography’s uneasy, but discernible, marriage to democracy or at least the significant point that images of common men and women were themselves common; indeed, it was not uncommon for such men and women to own photographs. Fenton’s photographic work contributed to democratization. He was a recognized public figure and the author of the column in the Times was disappointed that “Mr. Fenton did not remain a little longer” in the war zone (“Photography in the Crimea” 7). Presumably, he was also disappointed that Fenton remained away from the exhibition, recovering from ill-health. The photographer had little if anything to do with the physical display of his works.

More specialized periodicals included announcements and reviews with the authority of expertise. The Journal of the Photographic Society considered the show “the most remarkable and in certain respects most interesting exhibition of photographs ever opened” (“September 21st, 1855” 221). By 1855, that was not wholly faint praise, as photographs had been exhibited in various venues in London, ![]() Dublin,

Dublin, ![]() Paris, and elsewhere for the past five years. Those venues included the popular international and industrial exhibitions. The Society’s contributor encouraged “every one who can have the opportunity” to visit Fenton’s show (“September 21st, 1855” 221).

Paris, and elsewhere for the past five years. Those venues included the popular international and industrial exhibitions. The Society’s contributor encouraged “every one who can have the opportunity” to visit Fenton’s show (“September 21st, 1855” 221).

Several notices in The Art-Journal also encouraged attendance, suggesting the importance of the “large number of admirable photographs of incidents and events,” including those “connected with the siege of ![]() Sebastopol” (“Mr. Roger Fenton” 266). The editors concluded in a later column: “This is a collection of national importance” (“Photographs from Sebastopol” 285). The New York Daily Times special correspondent agreed, as he included “FENTON’s Crimean Photographs” in his “Affairs in England” column, just below an update on Queen Victoria and the Royal Family, presumably alongside other matters of “national importance” (“Affairs in England” 2, emphasis in original).

Sebastopol” (“Mr. Roger Fenton” 266). The editors concluded in a later column: “This is a collection of national importance” (“Photographs from Sebastopol” 285). The New York Daily Times special correspondent agreed, as he included “FENTON’s Crimean Photographs” in his “Affairs in England” column, just below an update on Queen Victoria and the Royal Family, presumably alongside other matters of “national importance” (“Affairs in England” 2, emphasis in original).

That enthusiasm was echoed by others—as we shall see below, not always without questioning and disagreement but always with engagement. The exhibition was not ignored or dismissed, either at the time or later by scholars. Among the issues with which Fenton and his contemporaries contended, and which have become subjects of important scholarly interpretation, was the question of realism or how truthfully did his images capture the war in the Crimea, if not war in general? In other words, were his images just propaganda and did other art forms represent war more truthfully? Could Fenton keep up with the changing conditions of the conflict, not to mention master the challenging physical conditions of the locale and overcome the technical limitations of his own tools? Reactions to the many photographs could not escape one foundational question about photography: was it a “science” or an “art,” and thus did the photographer act only as “a recorder and illustrator” of events, locations, and persons? Fenton’s successful “artistic” images of still-lives and landscapes contributed to the uncertainty about how to classify photography and photographers. This was an exciting time for the producers and consumers of photography and those questions about veracity and how to categorize the practice continued, at the very least, well into the next decade.[3]

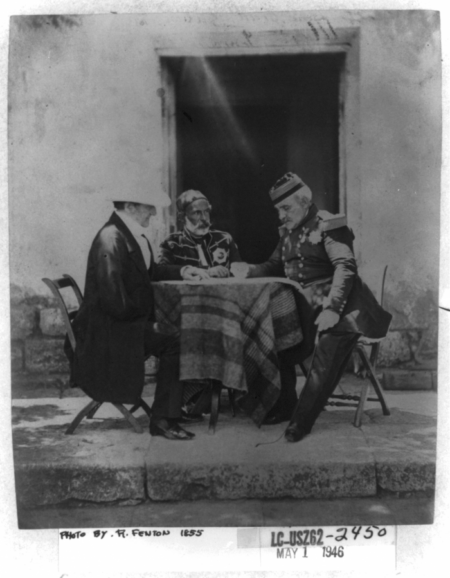

One might have asked such questions of the photographic image of Carlyle’s “leading men” of the much-maligned British, French, and Ottoman Turkish armed forces in such images as “The Council of War held at Lord Raglan’s Headquarters on the Morning of the Successful Attack on the Mamelon” (Figure 2). The official Catalogue noted that this and the other images were “intended to illustrate faithfully the Scenery of the Camps; to display prominent incidents of Military Life, as well as to perpetuate the Portraits of those distinguished Officers” (3). The immediate context was “the ever Memorable Siege of Sebastopol” and the figures included English, French, and Ottoman Turkish commanders (“Photographic Pictures of the Seat of War in the Crimea” 1141). Were the images “a truthful representation” or, as with other forms, were they a representational fiction or at least only truthful from one particular perspective? “Truthful” did not include the carnage of the Crimea, the mangled and dead humans and animals, but why should it? Answers include censorship, the demands of patriotism during war-time, and others considered by contemporaries and later scholars—most notably historians of photography and journalism.

Figure 2. Roger Fenton. “The Council of War held at Lord Raglan’s Headquarters on the Morning of the Successful Attack on the Mamelon.” 1855.

Such matters and doubts notwithstanding, the editors of Notes and Queries joined others in succinct messages: “Go and see the photographs from the Crimea!” they shouted from their pages (“Fenton’s Photographs from Crimea” 273). That was an unusual claim for a journal devoted to matters of Balzac, not Balaklava or in its publishers’ own words, “A Medium of Inter-Communication for Literary Men, Artists, Antiquaries, Genealogists, etc.” But that “Medium” and its readers could not or would not resist the compelling duet of war and photography.[4] If the War itself were not memorable, well, at least the photographs would make it so, and they themselves as objects were “memorable”. Not surprisingly, such enthusiasm subsided as the novelty of the show wore off and new events from the Crimea captured the public’s attention.

How popular were the shows? How many images were purchased from the accompanying Catalogue? I have not found financial statements concerning purchases or visitors’ or account books concerning admissions, but that could mean that I have not looked in the correct place(s).[5] Sophie Gordon has recently suggested that “about two million visitors” attended the different exhibitions by the end of March 1856, a figure derived from a contemporary notice in The Belfast News-letter (Shadows of War, 73; see also “The Crimean Photographs” 2).[6] The notice suggests a total for Great Britain, beyond the shows held just in England. That total is comparable to attendance at some of the larger international exhibitions of the period. Among the visitors were pupils at the School of Art at Marlborough House, who were provided with free admission to the first exhibition at the Water Colour Society (“Fenton’s Crimean War Photographs—The Exhibition of 360 Photographs” 1). For the general public, men, women, and children were invited and charged a few different rates. Adults were charged 1s per visit and could also take advantage of a season pass at 5s. Children could attend at half-price. Season passes were common at other exhibitions, as one way to increase overall attendance and purchases, and also, even if not always intended, to reduce the sense of being overwhelmed and fatigued trying to see and experience everything during only one visit.

The reduced admission for children strikes me as an important point: children were not to be shielded from these images of war, but people were encouraged to attend these exhibitions as families. This was a “day-out” for the family as there were only a few images which might shock the audience. Fenton’s photographs in 1855 were unlike many of those taken after the 1857-58 Rebellion in ![]() India had been ruthlessly crushed and those of Mathew Brady after major American Civil War battles, such as Antietam in 1862. The American’s photographs of the bloodiest day on American soil provoked Oliver Wendell Holmes, Sr. to write: “Let him who wishes to know what war is look at this series of illustrations” (“Doings of the Sunbeam” 11).

India had been ruthlessly crushed and those of Mathew Brady after major American Civil War battles, such as Antietam in 1862. The American’s photographs of the bloodiest day on American soil provoked Oliver Wendell Holmes, Sr. to write: “Let him who wishes to know what war is look at this series of illustrations” (“Doings of the Sunbeam” 11).

Scholarly Approaches to Fenton and His Photographs

Royal and elite patronage and the non-violent nature of Fenton’s images have led historians and others to conclude that the intention of the photographic enterprise and exhibition was propaganda or the production and public display of images which were not likely to be interpreted as criticisms of the War. As James R. Ryan writes: “Fenton’s record of the war presented a sanitized vision of a hopelessly managed campaign” (Picturing Empire 76), which can be contrasted with “the stark realism” of William Russell’s Times reporting. Ryan succinctly represents the general consensus among historians, including scholars of the history of photography, of which he is one of the most influential. There were a few images of wounded soldiers being tended to and of soldiers’ graves, although one cannot help but agree with Ryan that the photographic images of the wounds and the care seemed from a different world than Russell’s written descriptions in The Times. Many of Fenton’s images could have come from the theater or the photographer’s studio—Russell’s words from the battlefields themselves.

Ryan’s is only one of many scholarly discussions of Fenton’s war images. This brief contribution to that discussion is written with the full recognition of that scholarship. It is safe to say that Fenton and his Crimean images have not been ignored. Quite the contrary. Even a cursory review of available sources yields impressive studies of his life, photographic techniques and images (whether of the Crimean War or not), roles in the London Photographic Society and, with much evidence and conviction, the implications and legacies of those.[7]

Those publications include a volume of the Crimean War images with accompanying scholarly essays recently published by the Royal Collection Trust in England (Gordon, Shadows of War). That is not the first monograph devoted to those war photographs. There has also been focused scholarly appreciation and gallery shows of the non-Crimean photographs, landscapes, and still-lives among them.[8] Those included fruits, flowers, and buildings, and one might note that his war photographs had a “still-life” posed quality to them as well—the careful self-conscious positioning of physical objects according to artistic conventions as much as according to where they might naturally without mediation be in “The Seat of War.”

Fenton, his understanding of photography and place in the history of that practice, and his most significant images are also discussed in nearly all major and influential histories of photography.[9] Fenton’s images are easily accessed in the seemingly limitless public domain of the Internet via the courtesy of the Gernsheim Collection at the Harry Ransom Center, University of Texas at Austin, the Getty Archives, the Library of Congress, and the Royal Collection Trust. At least a handful will be readily recognized by most Victorianists. Those include “The Valley of the Shadow of Death,” with its allegedly post-“Charge of the Light Brigade” arrangement of cannon balls (Figure 3). That image and how it was set up are subjects considered by numerous scholars and by Erroll Morris—a prominent American documentary filmmaker.[10]

This essay engages some (not all) of that scholarship and might even redress some of the balkanization in scholarship about Fenton, early photography, and mid-Victorian culture and society. My hope is that this essay is of interest to political historians and historians of war, as well as historians of photography and culture. Perhaps the discussion might also be useful in the classroom as students study issues such as propaganda and the public views of war during the conflicts themselves. With such tall and broad scholarly shoulders upon which to stand, my goal in this brief essay is not to revisit important discussions about “realism” or even “war photography,” but in a far more mundane way to explore some of the public responses to the exhibition of Fenton’s images from the Crimea.

My contribution is not profound, but I hope helpful, by surveying how a sample of contemporaries responded in public to the first public exhibition devoted to contemporary images from a war and, of interest, a war which was not going particularly well or was especially popular at the time. What caught the eyes of those who took the time to reflect upon and write about the photographs? What might those responses suggest about attitudes towards the Crimean War and photography itself as well as how war and photography danced together during this time and place? What mattered to the exhibition visitors and commentators and why?

Some Public Responses to the Photographic Exhibitions

Trained as a traditional historian of Victorian Britain, I turned to printed sources to find some answers. Private correspondence might reveal nuggets, but I went right for the gold mine: the metropolitan press and the more specialized periodical literature. Keeping in mind the “classics” on Fenton and the history of photography noted above, I turned to the pages of The (London) Times, Illustrated London News, Notes and Queries, The Athenaeum, The Art-Journal, Manchester Guardian, Journal of the Royal Society of Arts and the Journal of the Photographic Society. Those and others paid healthy dividends and much more, revealing, not surprisingly, various different responses at the time of the first exhibition of Fenton’s Crimean War images, some responses more common than others.

That is a limited set of data in terms of social reach—I do not have a sense of what we call “popular culture,” yet I think I have in terms of “public opinion”—so I am only hesitantly making larger cultural, social or theoretical assertions, focusing on this selected group of articulate contemporaries who took the exhibition as an event and the images themselves with seriousness worthy of publishing extended thoughts. That need not be taken for granted. Many of those voices directly engaged the images with artistic and professional sensibilities and with questions being asked of photographers and photography during the mid-Victorian era. That such queries were also asked and answered during an unpopular and distant war makes for, at the very least, a lively historical context, one in which, for example, the question of “realism” was not an esoteric matter.

Each of those publications included more than a cursory gesture towards the first exhibition and often included commentary on the subsequent ones as well. Direct announcements or “notices” were common and the one to three printed columns then added extended discussion of the art form, the quality or lack thereof of key images, and of the photographic labors of Fenton and his assistant (for example, “Fenton’s Photographs from Crimea” 272-273 and “Fenton’s Crimea” 1). Such sober considerations unfolded after the above noted expressions of enthusiasm. After those accolades, contemporaries took the photographs and the subject of war seriously as just that: photographs (or a relatively new form of artistic or mechanical vision and reproduction) and a form that had not settled down to expected orthodoxies and authoritative institutions—one visualizing what visitors and readers understood as a “costly” and not necessarily successful war. Significant strategic successes were to come later.

There were few clear-cut, absolute rules for photography and thus few, if any, clear-cut rules for war photography as a sub-genre. Most histories of photography list Fenton as the first “war photographer,” and one could helpfully include his reminder at the Photographic Society in 1852 about “the present imperfect development of photographic knowledge” (“Abstract” 52). Modern warfare was also at that youthful, “imperfect,” if admittedly more deadly, stage, as commanders and strategists wrestled with changing rules and limited “knowledge.” What might the new rifles and cannons do? What might the camera do? Photography was fluid; war was also in flux. It was, to say the least, an interesting moment.

A commonly accepted appreciation early on was the novelty of the exhibition itself, as much as the novelty of the photographs themselves. This made sense since these were not the first military photographs, although they were the first series of photographs of armies at war. The exhibition was appreciated as the first time that so many photographic images of war (and only war) were gathered together for public viewing under one roof and during a war itself. Individual portraits of commanders had been available starting in the 1840s, but I have found no evidence of an earlier exhibition of such portraits or multiple military images.[11] On the other hand, there had been exhibitions devoted to photography and international exhibitions with photography exhibits by 1855. Among those were the English precedents of “The Exhibition of Recent Specimens of Photography,” organized by Fenton and the Photographic Society in 1852, and the displays of photographic images and technology one year before at the Great Exhibition housed in the ![]() Crystal Palace at Hyde Park.[12]

Crystal Palace at Hyde Park.[12]

For those compelled by matters of theory and philosophy, then and now, there were bold claims at the time about the historical and long-term significance of the images. This was a history of the present and a history for the future, before photos, too, could be appreciated for fading into nostalgia and memory or their own contribution to a manufactured past. The Illustrated London News noted without reservations in its second extended column about the first exhibition that “the historian of the war in future years will be seen bending over these memorials, and comparing them with the litera scripta of the correspondents of the journals, in order that…he may well ‘up’ in the features of the country and the bearing of those on its soil” (“Mr. Fenton’s Crimean Photographs” 557). The journalist was confident that “the historian” would do all of that before writing a single word.

The Crimean War was a conflict with relatively limited photography in contrast with the subsequent American Civil War, so it would be a leap to argue that Fenton and his colleagues held the same place in “memorializing” the conflict as would Brady and his colleagues. That does not diminish the understanding by observers of the potential historical use of Fenton’s work as a source for what happened as well as a shaper of how to understand what happened, and only suggests that one could not claim the dominance of his camera as Alan Trachtenberg does about the American Civil War’s cameras of Brady and his colleagues (“Albums of War”). Trachtenberg’s case is that the Civil War “enjoys a physical presence, a palpable cultural reality, entirely the legacy of a handful of photographs” (1). He suggests the fascinating concept of “historicism-by-photography, this notion that historical knowledge declares its true value by its photographability” (287). I defer to historians of photography to consider whether the American Civil War was the first historical example of that phenomenon, but mid-Victorians understood at least an historical value to Fenton’s photographs, if not a consensus that this was the “true value.” The distinction is not only a matter of the sheer volume of American Civil War photographs but also the subjects of so many of those later images and how they conferred a different and far less benign view of war and its battles.

Echoing claims that Fenton’s photographic images provided enduring and accurate chronicles, the editor of The Builder told his audience one month after the exhibition opened that “the improvements in photography…enabled the countenances of those who were so bravely fighting our battles in the Crimea to be handed down to posterity” (“The 1st Annual Meeting” 756). The editor thought of such projects as further evidence of “the wonderful progress which this age has made in science” (“The 1st Annual Meeting” 756). This is not to claim that matters of patriotism and sacrifice were ignored or absent. Sometimes comments explicitly referred to Fenton’s portraits as signs of a country’s “gratitude” for its men who had perished. That was the case with Notes and Queries (“Photographic Correspondence – Fenton’s Photographs from the Crimea” 273). Propaganda, if not patriotism, is not one unreasonable reading of such comments.

In reading such sources, a handful of other suggestive common responses stand out: Fenton faced demanding physical challenges and that gave value to the images, or at least increased appreciation of them; there remained consideration of the relationship between photography and art, or questions of beauty and aesthetics, which I think seem not to only be about the photographic process, but also about war itself, as if the photographic image of the Crimean landscape and military portraits captured a common perception of war as beautiful landscapes and portraits; and there continued fascination with the mechanics and methods of photography, over fifteen years after Talbot’s efforts in 1839.

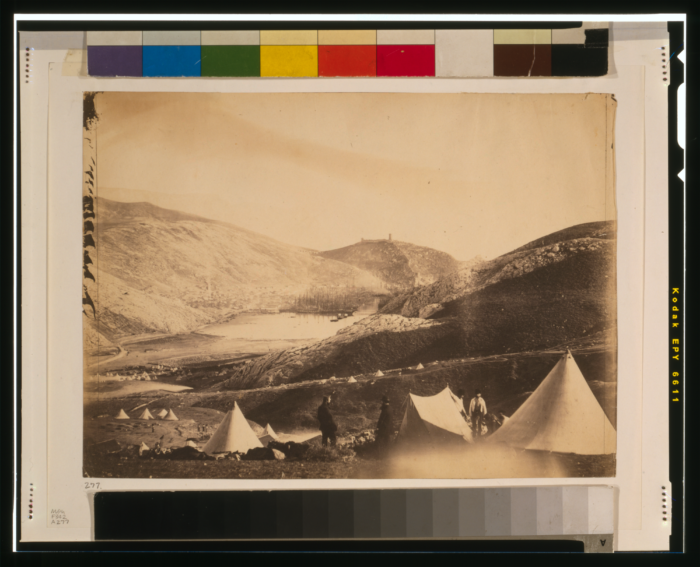

Fenton knew his art, subjects, and audiences. Many of his landscapes and still-lives were praised for their beauty, suggesting a relationship between photography and at least the profound goals of the Fine Arts.[13] That was also the case with how some responded to his Crimean War photographs. The Journal of the Photographic Society’s contributor concluded that “many of the pictures are excellent as photographs,” an appreciation of craftsmanship, and “some are very beautiful,” an appreciation of their aesthetics. Among those was No. 277, “A View of Balaklava from the Top of Guards Hill” (Figure 4). Other individual images received a disproportionate amount of attention in the sources I consulted. Those attention-grabbers included “The Council of War held at Lord Raglan’s Headquarters on the Morning of the Successful Attack on the Mamelon” (Figure 2). The Journal praised that one as “a real picture of a kind of subject often attempted ideally by painters” (“September 21st, 1855” 221, emphasis in the original). This was a seemingly classic group portrait, carefully staged, and became with the new technology and art “a remarkable study.” The subject itself—Lord Raglan, General Elissier, and Omer Pasha—might be considered “remarkable”, or at least unusual, in that it was this particular international trio.

This image did not escape The Art-Journal’s reviewer, who took time to clearly identify the “triad of celebrities” and the hour of the “consultation”—four o’clock in the morning (“Photographs from Sebastopol” 285). Their clothing is described, the various objects considered, and then a comment that no one else is in the picture assisting this council. It would be delightful to know Carlyle’s response to this peaceful image of those men of war he found so “incapable.” Not satisfied with the image itself, the Art-Journal asked about the circumstances of the seemingly unusual rendezvous. Was it “through some powerful interest that the artist was permitted to be present on such an occasion,” or, perhaps, was this a staged moment, as so many have asked also of “The Valley of the Shadow of Death?” (Figure 3).

The reader is left pondering as The Art-Journal column turns to listing many of the other portraits, both individual and group, including Ottoman Turkish, French, and British subjects: “There are none of the refinements of painting here” (“Photographs from Sebastopol” 285). In the case of at least one portrait, “there is nothing of the beautiful, but the beautiful of reality,” a claim not exactly echoing that made by the Journal of the Photographic Society (“Photographs from Sebastopol” 285). That is, it seems to assert photography as a science, rather than as an art, its aesthetics meeting the challenges of accuracy rather than of beauty. Perhaps Fenton’s images and other photographs could be both: an art form expressing the beauty of the Fine Arts and a craft or science living up to the demands of the accurate? Fenton was an active participant in discussions about such matters at Photographic Society meetings (for example, “Annual General Meeting”).[14]

The popular press engaged those questions and possibilities. The Illustrated London News praised the images and the photographer, or artist: “Mr. Fenton is an artist in the highest sense of the word; as we may see from the pose and grouping of his pictures” (“Exhibition of Photographic Pictures” 499). Images were recognized for their sense of beauty as well as “illustrative” and historical value. One was of “the highest interest as illustrative of the war”—with the understanding that illustrating war did not include violence and death—and another was “as finely executed as it is historically interesting” (“Exhibition of Photographic Pictures” 499). History, realism, contemporary events, and beauty could coexist with this relatively new form.

There were other contextually revealing reasons to applaud the Crimean War images. These are probably not surprising to historians, but still helpful to be reminded of. The Art-Journal considered the images both “novel” and “interesting,” the results of Fenton’s “unusual facilities for accomplishing his labors” (“Mr. Roger Fenton” 266). Those “facilities” included working in a war zone; such laborers with cameras were then and subsequently praised for their immediacy, courage and sense of danger. The slowly developing images of staged moments encouraged the sense that Fenton was on the frontlines facing proximate friendly and unfriendly fire. The Art-Journal concluded: “Several of the views have an especial [sic] interest, as being taken while the contending armies were under fire, to the dangers of which the photographist [sic] exposed himself equally with the combatants” (266). An advertisement high-lighted the images “taken by Mr. Fenton during the progress of the siege of Sebastopol,” the term “progress” perhaps being used with some sense of irony (“The Photographic Sketches” 1).

The theme of “this very arduous and really perilous enterprise” was picked up in a subsequent extended discussion of the Sebastopol images (“Photographs from Sebastopol” 285). The danger from Russian cannons and guns was highlighted, as were the physical “difficulties” and technical challenges of open-air photography. Physical and environmental challenges were commonly mentioned in discussion of outdoor, or natural photography, particularly foreign excursions. The Journal of the Photographic Society had noted that other photographers that same year had climbed the heights of mountains on the Continent up to 10,000 feet “in spite of the difficulties presented in the transport of baggage” (“”September 21st, 1855” 222).

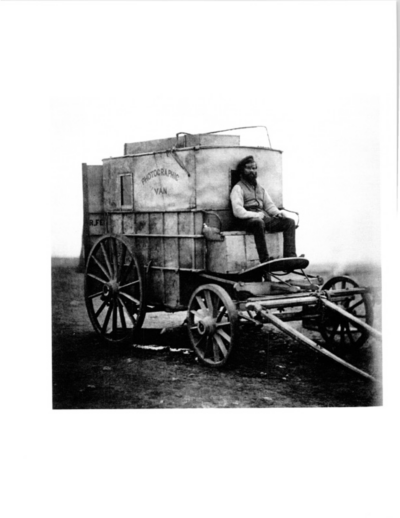

For Fenton, that “baggage” would include thirty-six large chests of equipment and his horse-drawn photographic van. That vehicle was not always easy to move about for nearly four months and could get quite heated from both the developing fluids and the outside temperature (Masterpieces of Victorian Photography 100-101;”Narrative of a Photographic Trip” 289). The press and periodicals noticed Fenton’s van. Some at the time claimed that the Russians thought it was an ammunition van, and thus they took aim at it. The Illustrated London News described the van in its pages in early November and provided an engraving adapted from one of Fenton’s onsite photographs (“Mr. Fenton’s Crimean Photographs” 557) (Figure 5).

Completing this common thread, the Illustrated London News thought that among the visitors “but few, perhaps, will be able to appreciate the difficulties under which Mr. Fenton, with rare skill and courage, succeeded in producing the admirable pictures” (“Mr. Fenton’s Crimean Photographs” 557). It was as if the photographer were himself at war—heat, labor, technology and the danger of cannon balls and bullet adding value to the material image. Fenton added details including “the plague of flies” (“Narrative of a Photographic Trip” 289). The second extended discussion in The Illustrated London News of the Crimean War photographs and exhibition also detailed the photographic process in the field, reducing the sense of natural magic and replacing it with a mechanical enchantment. “The unexampled interest as well as the extraordinary merit of the exhibition of photographs taken by Mr. Fenton in Crimea” had warranted a return to the subject for the paper (“Mr. Fenton’s Crimean War Photographs” 557).

That second article recounts Fenton’s movements with his “travelling van, or dark room, absolutely necessary for the purposes of taking these views and portraits” (“Mr. Fenton’s Crimean War Photographs,” 557). A steamer, a difficult horse, and Lord Raglan’s “extreme kindness” were all part of this travelogue to, through and from the war zone of the Crimea. The contributor claimed that Fenton was “frequently under fire” in the Crimea, particularly during the three days it took to complete a pair of photos: “The Valley of the Shadow of Death” and “The Panorama of Inkerman” (“Mr. Fenton’s Crimean War Photographs,” 557). “The Plateau of Sebastopol” was also a challenge, but the obstructions Fenton faced were less human and martial, and more environmental: the ground and the variation of the atmosphere. Again though, struggle, challenges, persistence, and work, but no mention of genius. Here was the heroic explorer and chronicler, as much, if not more than, the heroic artist. A bit later, Fenton would author and publish his own narrative of those challenges and how he overcame them (“Narrative of a Photographic Trip” 284-290).

The Wider and Continuing Life of the First Public Exhibition(s) of War Photographs

In practical terms, exhibition organizers and sponsors recognized the need to compete for public attention with other visual, oral and written representations of the War and to keep up with developments on the ground in the Crimea or with what today we might call “the news cycle.” The Illustrated London News notified its readers in late 1855 of such “additions to the original collection” and pointed out that they were included in “a double number in the catalogue, and marked with a star” (“Mr. Fenton’s Crimean Photographs” 557). New images included expected ones of British commanders, but perhaps a few unexpected or at least more surprising ones as well. The additions were a testament to changes on the ground in Crimea and some of the political implications of such changes.

There were images of French commanders and soldiers, and of a member of the “Sanitary Commission.” Some of those portraits included weapons, but no scenes of fighting or physical agony, at least not explicitly. One Zouave was pictured “bent on duty, and…cocking his weapon,” the visitor’s imagination necessary to generate the Russian soldier towards whom his weapon was presumably aimed (“Mr. Fenton’s Crimean Photographs” 557) . Organizers also added over time photographs taken by other photographers, making Fenton’s “memorable” within the mini and intertwined histories of this war itself and of photography, as those histories unfolded. Images were not necessarily “memorable” only because of their quality, but also because their immediate moment seemed to pass so quickly.

Driven by the thirst for new information and images conveying that information, exhibition organizers found space rather quickly as sieges, battles, and other aspects of the campaign unfolded. New images also made it more likely that visitors would return again after a previous tour of the exhibition. Additions made purchasing the season pass more sensible. The Guardian informed its readers in mid-January 1856: “Just added to the Collection: The Malakoff in ruins. Panorama of Sebastopol, with the destroyed houses. The Redan, after its evacuation. The Imperial Docks. And a Large Collection of Russian Arms” (1). Later in the year, readers of The Times learned that images from “Mr. Robertson, after the fall of Sebastopol” had been added to the exhibitions (“Fenton’s Crimean Photographs.—The Exhibition of 360 Photographs” 1). Fenton’s and Robertson’s images were credited the following year with showing “the public…the advantages that may be derived from” the practice of photography, “advantages” which included “a perfect record of whatever is visible” at the moment, as the moments moved from 1855 into 1856 (“Presidential Address” 303).[15]

Those and other photographic additions provided a sense of immediacy, mirroring the telegraph, pushing Fenton’s earlier images into the past. We think of our own news cycle as fast, if not sometimes out of control, and it is probably arrogant of us to think that the mid-Victorians did not sometimes think of their own cycle that way. Photographs, the telegraph, daily newspapers, and gossip created an unprecedented acceleration. Fenton later wrote that he “had hoped to add to the collection of views,” but left the Crimea in a convergence of military failures, the deaths “of friends,” and the “very unhealthy conditions” (“Narrative of a Photographic Trip” 290-291). Cholera was circulating, as was his “fever brought on by over-work and nervous excitement” (“Narrative of a Photographic Trip” 290-291).

Fenton’s and other photographers’ images of the War continued to be exhibited in London and at the Royal Exchange in Manchester well into the new year. Shows in ![]() Birmingham and

Birmingham and ![]()

Belfast were added in 1856 and those included images from other photographers as well (“Mr. Fenton’s Crimean Photographs” 7; “The Crimean Photographs” Birmingham Journal 3). Advertisements noted “the express patronage” of not only the Royal couple and ![]() Newcastle, but also of “the Emperor of the French,” and “the sanction of the commanders-in-chief.” The Guardian included in bold letters “William Russell, Esq. the Times’ Correspondent” as further endorsement and bait (“29 September 1855” 1, emphasis in the original). This invited the contemporary and later scholarly comparison of Russell’s reporting and Fenton’s photography, the organizers at the time hoping for a mutually helpful popular reception as truthful and newsworthy, although as Ryan and other scholars point out, this meant pairing Fenton’s relatively peaceful images and Russell’s rather blunt reporting. Other comparisons were made at the time between Fenton’s images and the many other forms of mid-Victorian visual and written representation. Those included journalism, engraving, drawing, painting, and poetry, among others, all of whom offered some gesture towards truthfulness and realism.[16]

Newcastle, but also of “the Emperor of the French,” and “the sanction of the commanders-in-chief.” The Guardian included in bold letters “William Russell, Esq. the Times’ Correspondent” as further endorsement and bait (“29 September 1855” 1, emphasis in the original). This invited the contemporary and later scholarly comparison of Russell’s reporting and Fenton’s photography, the organizers at the time hoping for a mutually helpful popular reception as truthful and newsworthy, although as Ryan and other scholars point out, this meant pairing Fenton’s relatively peaceful images and Russell’s rather blunt reporting. Other comparisons were made at the time between Fenton’s images and the many other forms of mid-Victorian visual and written representation. Those included journalism, engraving, drawing, painting, and poetry, among others, all of whom offered some gesture towards truthfulness and realism.[16]

Fenton’s photographs were also published by Agnew and Sons of Manchester in five portfolios under the title, Photographs Taken Under the Patronage of Her Majesty the Queen in Crimea by Roger Fenton, Esq. Portfolio groupings were: “Incidents in Camp Life,” “Historical Portrait Gallery,” “Views of the Camps,” and panoramas of Sebastopol and Balaclava (The Rise of Photography, 1850-1888 92-95). It was not unusual for contemporaries to gossip that the exhibitions were part of a strategy to advertise and sell these photographic albums. Mathew Brady sold similar ones at the time of the American Civil War less than ten years later.[17] There was without doubt a business side to Fenton’s exhibitions, and no one was shy about it, least of all Fenton, who was not anywhere near above and beyond self-promotion. The Catalogue included prices and an order form. Subscribers could choose one or more from the following categories: “Scenery,—Views of the Camps, &c.,” “Incidents of Camp Life,—Groups of Figures, &c.,” “Historical Portraits,” and “Miscellaneous Subjects,” for which the potential purchaser was advised to “See Catalogue” (“Exhibition of the Photographic Pictures taken in The Crimea” 16-17).

That was a particularly useful note for those who might be forgetful about specific images or, as was not unusual, were overwhelmed by the tiring and seemingly unlimited exhibition experience itself. Those were common experiences for exhibition visitors during the era. Such sensible rationales ignore one additional one: ordering from the illustrated Catalogue invited those who did not attend to still participate by owning the images and, unlike some purchases from other exhibitions, the images need not be originals but were recognized as reproductions. Purchasers had a significant number of choices for their final orders, which was not always the case, as the exhibition catalogues for other events often were used in part to distinguish what was available for purchase from what the commissioners, exhibitors or some other source had determined was not for sale. One might conclude that Fenton’s images were wartime souvenirs for some.

Messrs. Agnew and Sons joined Fenton as the entrepreneurs and salesmen in this story converging not only the recognized commercial appetites for what was seen in public at an exhibition, often for the first time, but also war and photography. A Manchester publisher, Thomas Agnew, financed Fenton’s trip to the Crimea, intending to take advantage of these different strands woven together in a potentially money-making enterprise. In this case, perhaps all of the public controversies about the War did not hurt the efforts, but provided additional (and free) publicity. Newspapers carried notices, informing readers about patrons, venues, times, and admission prices. Occasionally, there would be an additional direct and supportive tweak such as when a notice in Notes and Queries in October included one final commercial tease: “Catalogues forwarded by post on receipt of six postage stamps” (“Exhibition of the Photographs Taken in the Crimea” 1). This was a mutually beneficial relationship.

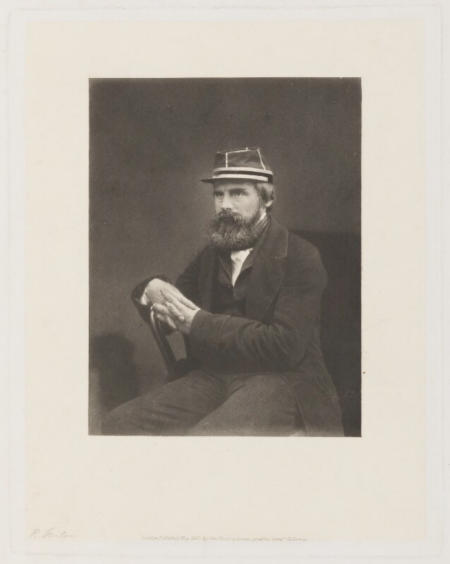

The Agnew firm, organizers, and the photographer himself took advantage of the contemporary press and periodicals. Fenton was not unlike his more famous contemporary, Charles Dickens, both knowing how to exploit new technologies for publicity and commercial purposes. Photography was among the most effective of those innovations, and Dickens, Fenton and others staged self-promotional photographs. Hugh W. Diamond’s photogalvanograph in 1868 of Fenton shows the photographer wearing a military cap, many years after his Crimean exhibition—a gesture to his “memorable” war photographs (Figure 6). Ironically, by then, Fenton had retired from photography and was a professional solicitor, but no one could ignore the reference to his war photographs of over ten years before.

Seeing the Crimean War Back Home in Britain

There was considerable public interest in the War, represented in part by the occasional exhibition of drawings and paintings, the nearly daily newspaper reports and engravings of events, persons and campaigns and numerous lectures. (“Water Colour Drawings of the War” 12). Speakers toured England at the time, lecturing to Mechanics’ Institutes and in other civil society venues on topics including “The Siege of Sebastopol.”[18] I mention those to suggest that the public reactions to Fenton’s images can also include that competition for public attention. In terms of visual representational genres, Fenton’s photographs had competition not only for attention and money but also attention for which artist and which genre could make a claim to “realism” or “truthfulness” or which could be most patriotic. Which genre might best represent the public’s understanding or expectations of war? Ulrich Keller notes that the variety and quantity of the visual representations of the Crimean War amounted to a spectacle, what he calls, “the ultimate spectacle.”[19]

Figure 6. Hugh Welch Diamond. Photogalvanograph of Roger Fenton. 1868.

Source: National Portrait Gallery, NPG P226.

Fenton’s images are among the examples Keller includes in his study, and the variety of visual and other representations reminds us that photography did not dominate the field of representation and later reflection, as Trachtenberg argues that it did for the American Civil War. That variety during the 1850s provoked contemporaries to ask whether engravings, drawings or photographs captured most realistically the experiences of war, and how and why? Or, perhaps more accurately, which represented what folks back home thought were the realities of war? Contemporaries were and scholars remain intrigued by that question. I include myself, as the materials I reviewed directly addressed the matter of which genre they would recommend. Which was more true to what a contributor to the Art Journal termed, “the stern realities of [the] giant contest,” or any such “contest” (“Reviews: The Seat of War in the East” 196)? Again, I refer to the existing superb scholarship, only to focus on a link between those viewing Fenton’s images in 1855 and a question asked seven years later during the American Civil War. Was “the object” of photography, including Mathew Brady’s at the time, to give “an idea of what a ‘battle is like’?” (“American Photographs” 184).

What an interesting question, as it not only asks about the ability of photography and the photographer or their goals but also what constituted a “battle” and whether war was understood in terms of battles. Appreciating what many scholars have written about Fenton’s war images and their relationship to “realism,” I would slightly tweak that relationship by asking what Fenton and his viewers thought “battles” and “war” were and, thus, at one level of comprehension and expectation, whether they conceived war as battles or a series of battles, or was “war” something else? If war could be understood as something in addition to or rather than battles, or expected to be something else, then we have a complementary but slightly different matter to consider.

If the mid-Victorian public wanted to see images of battles or thought of warfare as battles, then such men, women, and children would have been disappointed by Fenton’s photographs from the Crimean War. If war were the movement of armies in battles, set-pieces of motion, then at least some contemporaries thought that war could be more truthfully represented by lively drawings and paintings rather than by the stillness of the slowly developing camera image. That stillness, as Fenton understood, provoked more of one’s imagination, providing less direct information about the moments of violence but plenty of information to make suggestions about such moments. It was a profound stillness. Portraits and landscapes of the Seat of War invited the viewer to fill in the lacuna of the battle if that was how they understood war, or they could be visually satisfied by enjoying portraits and landscapes.

What about how drawings represented the Crimean War and war in general? The Art-Journal recognized and praised on-site drawings, such as those published during the first year of Fenton’s exhibition. The public show, The Seat of War in the East. From Drawings taken on the Spot, earned a favorable review in the esteemed journal, the author commenting that the sixteen plates “are the best pictorial series of the incidents of the Crimean campaign, that we have yet seen” (“Reviews: Drawings from the Seat of War in the East” 196). Why was that the case? The drawings faithfully represented “the stern realities of [the] giant contest” with, yes, “saddened feelings,” but without sacrificing “the fortitude and heroism that have marked the conduct” of English soldiers and sailors—and their allies. War was battles to this reviewer —confrontations with drama, victory, and death.

The drawings captured those. “Quiet,” “hard-working,” and “bloody” days were all present in different drawings as were days of “anguish” (“Reviews: Drawings from the Seat of War in the East” 196). Such “extreme fidelity” included topographical and burial scenes, leading the observe to conclude that the collection “may be called a pictorial history” (“Reviews: Drawings from the Seat of War in the East” 196). That is, a history of the present. War had its death and destruction, and it also had its boredom—both “days of sunshine and days of snow storms.” If the appetite for such a drawing from the Crimea were not satisfied, Londoners and their out-of-town guests could visit in early 1856 at least one more exhibition: “Water Colour Drawings of the War in Bond Street” (“Water Colour Drawings” 12).

In one other case from the time and place, the pages of the popular Illustrated London News were filled with engravings of war. Those did not meet the standards of photographers—for many reasons, professional, monetary, and aesthetic among them—although engravings were commonly adapted or reproduced from photographs (“Witness to War,” 371-375). Fenton was adamant that sketches in the ILN were inadequate, and his reasoning is revealing. It is not only a claim about the art form but also about what the art form is intended to represent: war. He wrote to his publisher that Thomas Goodall’s sketches of war “seem to astonish everyone here from their total want of likeness to reality, and it is not surprising that it should be so, since you will see from the [photographic] prints sent here with that the scenes we have here are not bits of artistic effect which can be effectually rendered by a rough sketch, but wide stretches of open country covered with an infinity of detail” (Masterpieces of Victorian Photography 11). As an historian of culture, that statement echoes with more than an aesthetic criticism. It also seems informed with an understanding of war, or how war should be represented. War was a landscape, or “open country,” filled with “detail,” and not the mobile and dynamic clash, movements of which sketches and Lady Butler’s battle paintings could represent but photography could not.

Recognizing Fenton’s criticism, which did not completely transcend self-interest, a quick perusal in the 1850s, 1860s, and 1870s leaves one with a nearly limitless number of engraved press images from the Crimea, the Italian Campaigns, and the Franco-Prussian War. One could throw in the Spanish Wars as well. War was good for the press and vice versa; readers wanted movement, not only landscape or logistical moments. Here was a claim not only about the specific representational genre but also about how war was understood. Those nearly weekly images provided a constant and expected visualization of war. The mid-Victorian engravings achieved a “normalcy” of war as battles. Lady Butler’s paintings were more likely to come to the rescue of the popular appetite for images of war than Fenton’s photographs.

Concluding Thoughts and Questions

Although the Times wished he stayed in the Crimea, Fenton was relieved to be home. One also wonders how committed he was to photographing a war that could less and less be represented by portraits, landscapes, and logistics, and that rather increasingly called out to be represented by “men with pale waxen faces and ghastly wounds,” Fenton’s echo of Susan Sontag’s memorable late twentieth-century claim that war photography represents and illustrates “the pain of others” (“Narrative of a Photographic Trip” 290)?[20] That was not the subject of Fenton’s own war photographs. This was not what his sponsors and patrons had sent him out to represent and, in that case, it is true that he avoided what would have been critical of the war effort. But I might suggest that it is also true that such “ghastly wounds” were not his understanding of war itself until later in his visit. The earlier understanding was informed by the aesthetic framing and requirement of war in terms of portraiture and landscapes and the material ones of logistics.

The “realities” of disease and wounds called not only for a different approach to what could and should be photographed but also for a photographer with a different understanding of what war was and how to represent its reality with the camera. This is not to suggest that Fenton was naïve but to suggest that he represented a particular understanding of war and an understanding of how the camera could be used. Photography and war were ripe for a new relationship as both meanings were changing, a topic that has generated much informative scholarship. I would only add that “war” was the fundamental subject of Fenton’s images if we think of war without pitched battles, corpses, and “the pain of others”—perhaps many mid-Victorians did?

Was it natural to expect physical carnage or destruction? Concluding that Fenton did not want to offend with corpses and destruction because of the demands of propaganda is not incorrect. It downplays, though, the power of aesthetic conventions and how they interacted with perceptions of war itself or what it should be. Being a gentleman and a photographer included not showing dead bodies from battles and not showing dead bodies according to the conventions of landscape and portraiture, although being a gentleman and a photographer did not prevent appealing to the imaginative qualities of the images and what they might provoke in those attending the exhibitions. Those powers of the imagination were assisted and fueled by many sources, not least of which would have been the other available images of the War and of war itself.

Fenton could very well have argued consistently with his previous writings and talks that a field with cannon balls invites the “disposition of mind” to imagine horrors as well as nobility (“Abstract” 52). Ironically, he might be far more modern than his critics claim of him and also his images, including number 218, the famous “The Valley of the Shadow of Death” (Figure 3). No drama other than with association, but for contemporaries that was a powerful association, one which would leave the viewer of the camera’s work with, in Fenton’s terms, “the exercise of judgment, the play of fancy, and the power of invention.” He continued in his paper read in 1852 before the Photographic Society, that photography was not “a kind of power-loom” but also not like a drawing, or at least full drawing (“Abstract” 51). Photographic images from the Crimea, particularly the landscapes, were more like poems: the less one wrote, the more one could read into them. It was the absence of images that mattered, or the combination of “the most faithful transcript of nature” and “the play of fancy” (“Abstract” 51). After all, as Fenton claimed, “[e]very disposition of mind has its bodily expression,” including dispositions about war and peace (“Abstract” 52)

Among other historians and critics, Reuel Golden remarked that “The Valley of the Shadow of Death” (Figure 3) “is a picture almost bereft of information about the battle itself” (“Roger Fenton” 74). He and his colleagues are, in one sense correct, but they also might be missing the sense that war was not only battles for at least some mid-Victorians. Cannonballs on the ground are not intended to tell an unproblematic narrative, unlike the goals of propaganda. Rather, images such as that one invite, if not demand, the viewer to ponder what had happened to put those cannon balls where they are now. Into that imagination, or that void, would run preconceptions about landscape, the Crimea and warfare itself. Perhaps Tennyson’s poem might even help fill that apparent blank slate?[21] Fenton understood that the photographic image did not deny but rather invited the information and imagination that viewers bring to the image, including those men, women, and children who toured the first exhibition of war photography in 1855 as they consumed the many representations of the Crimean War available to them.

I have tried to read those readers of the photographs, figuring out not what the images should have meant or could have meant but what they did mean for the men and women who took note of the Exhibition and thought it worthwhile to comment upon and thus add to the often influential mid-Victorian “public opinion.” A contributor to that opinion wrote in The Leader, only two days after Fenton’s show opened, that photography was “History’s Telescope” (“History’s Telescope” 914-915). That is, “the means of possessing the impress of things which we desire to see, and of conveying the impress to distant places,” including what mid-Victorians desired to see in the Crimea (“History’s Telescope” 914). “Do you desire things as they are in the Crimea,” he queried? “If so, then go down to Pall Mall East,” The Water Colour Society, pay the shilling, and see Fenton’s images of Sebastopol and many officers, including Lord Raglan” (“History’s Telescope” 914-915).

The Lord Raglan featured in that image could not escape the Lord Raglan targeted by Carlyle’s caustic pen or that of other critics. But Fenton offered a softening of those weapons by providing “the mode in which the officers have lived” and “you may see – precious to the eyes of anxious affection – exactly how they have lived” (“History’s Telescope” 914-915). Or, more precisely, how one thought they had lived, not only inspired by patriotism but also by an understanding of war as portraiture and landscape. That understanding was in itself a contextual definition of “truthful,” one seen and preserved by photography, “history’s telescope,” or an apparatus that can bring what is distant near. That distance can be temporal, physical and even existential. Fenton appreciated that.

We can take seriously and apply Fenton’s earlier writings about the power of photographs to work on the imagination, for images to provide the before and after of the particular moment captured in black and white, a capturing which made that moment “memorable” and “truthful” in a surprisingly modernist way. A fellow member of the Photographic Society recognized the power of Fenton’s framing. He offered the term “terrible suggestion” when describing the powerful interpretations from that famous nearly “empty” image: “The Valley of the Shadow of Death” (“September 21st, 1855” 221) (Figure 3). In this case, “cannon-balls lying strewed like moraines of a melted glacier through the bottom of the valley” (“September 21st, 1855” 221). The “suggestion” or association—the fateful and tragic Charge of the Light Brigade. The cannon balls were sufficient and necessary to generate the “suggestion.”

The story of Fenton’s exhibitions reminds us of the many claims connecting propaganda and patriotism, or the nobility and purpose of war, whereas my sense is that if propaganda were effectively connected to anything else, it was that war was no different than other human activities and physical environments, and thus could be represented by the conventions of portraiture and landscapes. Perhaps that is the most powerful form of war propaganda: not martial spirit or militarism, sacrifices, jingoism, patriotism, or blood-lust but making war natural and no different than the rest of society and human existence. If that is the case, then perhaps Fenton was producing propaganda, a propaganda that continued the longer-term narratives of normalizing and naturalizing war, and he was doing so in a way that revealed the naturalization of the new science, or art, of photography in the case of the changing material realities of increasingly modern warfare—in this case, by comparing war and photographs of landscapes, war and photographic individual and group portraits. As Holmes, Sr. suggested, all of those atoms would change in the new molecular fusion of modern society, war, art and photography: “The time is perhaps at hand when a flash of light, as sudden and brief as that of the lightning which shows a whirling wheel standing stock still, shall preserve the very instant of the shock of contact of the mighty armies that are now gathering” (“The Stereoscope and the Stereograph” 748). But that is the topic of future reflections.

published November 2021

HOW TO CITE THIS BRANCH ENTRY (MLA format)

Hoffenberg, Peter H. “The Official Opening of ‘The Exhibition of the Photographic Pictures taken in The Crimea by Roger Fenton, Esq.’” BRANCH: Britain, Representation and Nineteenth-Century History. Ed. Dino Franco Felluga. Extension of Romanticism and Victorianism on the Net. Web. [Here, add your last date of access to BRANCH].

WORKS CITED

“Affairs in England.” New York Daily News, 16 October 1855, p. 2.

“American Photographs.” The Journal of the Photographic Society of London, vol. 8, 1862, pp. 184-186.

“Annual General Meeting.” The Journal of the Photographic Society, vol. 2, no. 39, 1856, pp. 299-304.

“The 1st Annual Meeting of the Berks and Bucks Lecturers’ Association in Windsor.” The Journal of the Royal Society of Arts, vol. 3, no. 151, 1855, pp. 755-757.

Baldwin, Gordon. Roger Fenton: Pasha and Bayadere. J. Paul Getty Museum, 1996.

Baldwin, Gordon, et al. All the Mighty World: The Photographs of Roger Fenton, 1852-1860. Yale UP, 2004.

Brothers, Caroline. War and Photography: A Cultural History. Routledge, 1997.

Burn, W. L. The Age of Equipoise: A Study of the Mid-Victorian Generation. W. W. Norton and Company, Inc., 1964.

Campbell, Ian, et al., eds. The Collected Letters of Thomas and Jane Welsh Carlyle, Duke-Edinburgh Edition, Volume 30, July-December 1855. Duke UP, 2002.

Clayton, Owen, ed. Literature and Photography in Transition, 1850-1915. Palgrave, 2014.

“The Crimean Photographs.” The Belfast News-Letter, 31 March 1856, p. 2.

“The Crimean Photographs.” Birmingham Journal, 16 February 1856, p. 3.

Edwards, Steve. The Making of English Photography/Allegories. The Pennsylvania State UP, 2006

“Exhibition of Photographic Pictures from the Seat of War in the Crimea.” The Illustrated London News , 27 October 1855, pp. 45-99.

“Exhibition of Photographic Pictures of the Seat of War in the Crimea.” Illustrated London News, 27 October 1855, p. 499.

“Exhibition of Recent Specimens of Photography.” Journal of the Royal Society of Arts, vol. 1, 1852, pp. 61-63.

Exhibition of the Photographic Pictures taken in The Crimea, By Roger Fenton, Esq. During the Spring and Summer of the Present Year, at the Gallery of the Water Colour Society, No. 5, Pall Mall East. Messrs. Thomas Agnew and Sons, 1855.

“Exhibition of the Photographs Taken in the Crimea.” Notes and Queries, vol. 12, no. 312, 1855, p. 1.

Fenton, Roger. “Narrative of a Photographic Trip to the Seat of War in the Crimea.” Journal of the Photographic Society, vol. 2, no. 38, 1856, pp. 284-291.

Fenton, Roger. “Abstract of ‘On the Present Position and Future Prospects of the Art of Photography’.” Journal of the Society of Arts, vol. 1, no. 5, 1852, pp. 50-53.

“Fenton’s Crimean Photographs.—The Exhibition of 360 Photographs.” Times, 12 May 1856, p. 1.

“Fenton’s Crimea.” Manchester Guardian, 22 September 1855, p. 1.

“Fenton’s Photographs from Crimea.” Notes and Queries vol 12, no. 312, 1855, pp. 272-273.

Flukinger, Roy. The Formative Decades: Photography in Great Britain, 1839-1920. U of Texas P, 1985.

Gernsheim, Helmut. Masterpieces of Victorian Photography. Phaidon Press, 1951.

———. The Rise of Photography, 1850-1880: The Age of Collodion, The History of Photography, Volume II. Thames and Hudson, 1988.

Gervais, Thierry. “Witness to War: The Uses of Photography in the Illustrated Press, 1854-1904.” Journal of Visual Culture, vol. 9, no. 3, 2010, pp. 370-384.

Golden, Reuel. Photojournalism 1855 to the Present. Abbeville Press Publishers, 2009.

Gordon, Sophie. Shadows of War: Roger Fenton’s Photographs of the Crimea, 1855. Royal Collection Trust, 2017.

Groth, Helen. “Technological Mediations and the Public Sphere: Roger Fenton’s Crimea Exhibition and ‘The Charge of the Light Brigade’.” Victorian Literature and Culture, vol. 30, no. 2, 2002, pp. 553-570.

Hambler, Anthony. Photography and the Great Exhibition. Oak Knoll Press and V&A Publishing, 2018.

Hannavy, John. Roger Fenton of Crimble Hall. Gordon Fraser Gallery, 1975.

Hariman, Robert, and John Louis Lucaites. The Public Image: Photography and Civic Spectatorship, The U of Chicago P, 2016.

Henisch, B.A., and H.K. Henisch. “James Robertson and his Crimean War Campaign.” History of Photography, vol. 26, no. 4, 2002, pp. 258-268.

“History’s Telescope.” Leader, 22 September 1855, pp. 914-915.

Holmes, Sr., Oliver Wendell. “Doings of the Sunbeam.” Atlantic Monthly, vol. 12, no. 69, 1863, pp. 1-15.

Holmes, Sr., Oliver Wendell. “The Stereoscope and the Stereograph.” Atlantic Monthly, vol. 3, no. 20, 1859, pp. 738-748.

Keller, Ulrich. The Ultimate Spectacle: A Visual History of the Crimean War. Routledge, 2001.

Leonardi, Nicoletta, and Simone Natale, eds. Photography and Other Media in the Nineteenth Century. The Pennsylvania State UP, 2018.

Linfield, Susie. The Cruel Radiance: Photography and Political Violence. The U of Chicago P, 2010.

Marien, Mary Warner. Photography: A Cultural History, 3rd ed. Prentice Hall, 2011.

Morris, Errol. Believing is Seeing: Observations on the Mysteries of Photography, Penguin Press, 2011, pp. 2-71.

“Mr. Fenton’s Crimean Photographs.” Illustrated London News, 10 November 1855, p. 557.

“Mr. Fenton’s Crimean Photographs.” Birmingham Journal, 9 February 1856, p. 7.

“Mr. Roger Fenton.” The Art-Journal, vol. 1, 1855, p. 266.

“Mr. Roger Fenton’s Photographs of the Seat of War.” Guardian, 11 September, 1855, p. 3.

O’Neill, Morna. “Making Art in the Age of Industry: Paintings by George Lance and Photographs by Roger Fenton.” Victorian Studies, vol. 62, no. 2, 2020, pp. 230-243.

Pare, Richard. Roger Fenton. The Aperture Foundation, 1987.

“Photographic Correspondence – Albumenized Collodion.” Notes and Queries, vol. 12, no. 312, 1855, pp. 310-311.

“Photographic Correspondence – Fenton’s Photographs from the Crimea.” Notes and Queries, vol. 12, no. 310, 1855, pp. 272-273.

“Photographic Correspondence – New Stereoscopes.” Notes and Queries, vol. 12, no. 312, 1855, pp. 310-311.

“Photographic Pictures of the Seat of War in the Crimea.” The Athenaeum, no. 1458, 6 October 1855, p. 1141.

“The Photographic Sketches.” The Guardian, 26 November 1855, p. 1 and reprinted 28 November 1855, p. 1.

“Photographs from Sebastopol.” The Art-Journal 1,1855, p. 285.

“Photography in the Crimea.” Times, 20 September 1855, p. 7.

“Proceedings of Institutions.” The Journal of the Society of Arts, vol. 4, no. 160, 14 December 1855, p. 63.

“Reviews. The Seat of War in the East. From Drawings Taken on the Spot.” The Art-Journal, vol. 1, 1855, p. 196.

Royal Society of Arts (Great Britain). A Catalogue of an Exhibition of Recent Specimens of Photography Exhibited at the House of the Society of Arts, 18 John Street, Adelphi, in December 1852. 2nd ed., Charles Whittingham, 1852.

Ryan, James R. Picturing Empire: Photography and the Visualization of the British Empire. The U of Chicago P, 1997.

“September 21st, 1855.” The Journal of the Photographic Society, vol. 2, no. 34, 1856, pp. 221-222.

Sheehan, Tanya, and Andris Zervigon. Photography and Its Origins. Routledge, 2015.

Siegel, Steffen, ed. Writings from the Beginning of Photography. J. Paul Getty Museum, 2017.

Smith, Lindsay. “Roger Fenton’s Nature More: The Pull of Sculpture.” History of Photography, vol. 37, no. 4, 2013, pp. 397-411.

Sontag, Susan. Regarding the Pain of Others. Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2003.

“29 September 1855.” Guardian, p. 1.

Taylor, John. Body Horror: Photojournalism, Catastrophe and War. New York UP, 1998.

Trachtenberg, Alan. “Albums of War: On Reading Civil War Photographs.” Representations, vol. 9, 1985, pp. 1-32

“Water Colour Drawings of the War in Bond Street.” Times, 21 February 1856, p. 12.

Weaver, Mike. British Photography in the Nineteenth Century: The Fine Art Tradition. Cambridge UP, 1989.

Wilcox, Timothy. The Triumph of Watercolour: The Early Years of the Royal Watercolour Society, 1805-1855. Philip Wilson Publishers, 2005.

ENDNOTES

[1] See Burn, The Age of Equipoise.

[2] The most recent comprehensive history of the War is Orlando Figes, The Crimean War.

[3] Scholarly discussions about the uses, meanings, and nature of early photography include Steffen Siegel; Tanya Sheehan and Andris Zervigon; Owen Clayton; Steve Edwards; and Nicoletta Leonardi and Simone Natale.

[4] Notes and Queries included columns about photographic processes, technologies, and images. For example, see “Photographic Correspondence. Albumenized Collodion-M. Taupenot’s Process” and “New Stereoscopes.”

[5] Please note that there is no reference to Fenton’s exhibition in Timothy Wilcox, The Triumph of Watercolour. I intend to visit and review in person the Society’s archives when international travel returns. The archives include: General Meeting and Committee Minute Books, Balance Sheets, Account Books and Extracts from Minutes.

[6] “THE CRIMEAN PHOTOGRAPHS.—We have pleasure in announcing that these photographs of the principal persons, scenery, and events in the Crimea, taken by Roger Fenton, Esq., are now being arranged by our towns-man, Mr. Magill, for exhibition in Belfast. The pictures have received the marked approval of her Majesty, and have been visited by more than two million persons in the various towns where they were exhibited. The portraits are said to be faithful, and the scenery represented vividly impressive.” Source: “The Crimean Photographs,” The Belfast News-Letter, 31 March 1856, p. 2.

[7] See Baldwin et al, All the Mighty World: The Photographs of Roger Fenton, 1852-1860; Gordon Baldwin, Roger Fenton: Pasha and Bayadere; John Hannavy, Roger Fenton of Crimble Hall;and Richard Pare, Roger Fenton, New York: The Aperture Foundation, 1987.

[8] For example, see Mike Weaver’s chapter “Roger Fenton: Landscape and Still Life,” pp. 103-120.

[9] See Roy Flukinger, The Formative Decades: Photography in Great Britain, 1839-1920; Helmut Gernsheim, Masterpieces of Victorian Photography; Helmut Gernsheim, The Rise of Photography, 1850-1880: The Age of Collodion, The History of Photography, Volume II; and Mary Warner Marien, Photography: A Cultural History, 3rd ed.

[10] As is the case with others, Morris ponders whether the cannon balls famously in the road in Fenton’s “Valley of the Shadow of Death” were placed there, or did Fenton find them there? Does the answer matter and, if so, why and to whom? See Morris, Believing is Seeing: Observations on the mysteries of Photography.

[11] For more information on commanders’ portraits, see The Formative Decades, specifically page 27.

[12] The most comprehensive scholarly study of photography, photographers and photographic materials at the Crystal Palace in 1851 is Anthony Hambler, Photography and the Great Exhibition. Helpful contemporary information is included in the various official catalogues and reports under “Class X. Philosophical Instruments and Processes Depending Upon Their Use.” Also see A Catalogue of an Exhibition of Recent Specimens of Photography.

[13] For helpful discussions of Fenton’s photography and mid-Victorian Fine Arts, please see Morna O’Neill and Lindsay Smith.

[14] Early in the Society’s discussion, Fenton stated that “We are engaged in perfecting and bringing into practical use an art which is destined to become of immense service to industry, to science, and to art” (“Annual General Meeting” 301). One speaker responded that “[t]he real name of photography is, that it is a practical science” (303).

[15] For a discussion of Robertson’s war photographs, please see B. A. Henisch and H. K. Henisch, “James Robertson and his Crimean War Campaign.”

[16] See Gervais, “Witness to War: The Uses of Photography in the Illustrated Press, 1854-1904.”; Groth, “Technological Mediations and the Public Sphere”; Keller, The Ultimate Spectacle.

[17] See Trachtenberg, “Albums of War: On Reading Civil War Photographs.”

[18] “Stalybridge.—On the 19th inst., J. D. P. Astley, Esq. (Lord of the Manor of Dukenfield), who has lately returned from the Crimea, delivered a lecture at the Town Hall, to the members and friends of the Mechanics’ Institution, “On the Siege of Sebastopol,” in which he described in a familiar manner, the operations of the siege, offensive and defensive, from the commencement, in 1854, to the fall of Sebastopol” as noted in The Journal of the Society of Arts, 1855.

[19] See The Ultimate Spectacle 119-171.

[20] Significant studies of photography, violence (including war), and related questions of ethics, if not a type of pornography, include Caroline Brothers, War and Photography: A Cultural History; Susie Linfield, The Cruel Radiance: Photography and Political Violence; Robert Hariman and John Louis Lucaites, The Public Image: Photography and Civic Spectatorship; Sontag, Susan. Regarding the Pain of Others. Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2003. John Taylor, Body Horror: Photojournalism, Catastrophe and War.

[21] See Groth, “Technological Mediations and the Public Sphere.”