Abstract

Opened to the public in 1830, the Liverpool and Manchester Railway effectively inaugurates the modern railway era. This essay sketches the construction of the L&M, the memorable events of its opening day, and its impact upon representations of the railway and its risks. The opening of the L&M reveals the tumultuous political dynamics of pre-Reform Bill Britain as well as deep uncertainties about industrial modernity, encapsulated by a fatal accident to MP William Huskisson.

In 1902, H.G. Wells claimed that the defining symbol of the nineteenth century was “a steam engine running on a railway” (4). On September 15, 1830, that symbol debuted at the opening of the ![]() Liverpool and

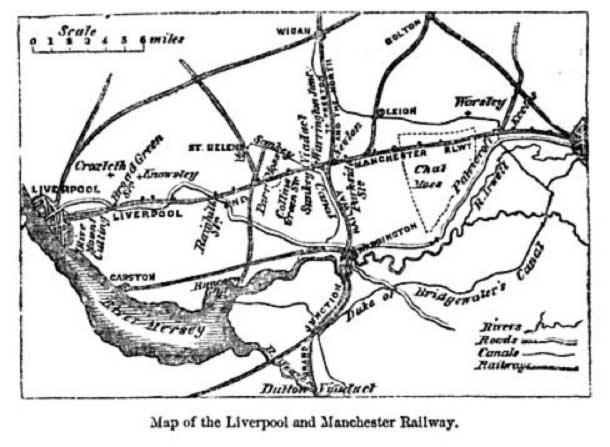

Liverpool and ![]() Manchester Railway. (See Fig. 1.) The L&M was neither the world’s first railway, the first to carry passengers, nor the first to use steam-powered locomotives. But it represents the first incarnation of the railway in its modern form: driven entirely by steam locomotive, connecting crucial industrial cities, and captivating a fascinated, even anxious public. The L&M’s immediate commercial success helped to invigorate the financial speculations and railway construction projects whose economic, physical, and cultural consequences were epochal. For so many observers who witnessed it or who read the widespread reports, the opening of this line inaugurated the railway era for better and worse. Its public commencement tracks the spectrum of attitudes—from celebrations of its commercial potency to astonishment at the experience of traveling at high speed (25 miles per hour!) to shocked apprehension of its serious dangers—that would come to characterize the railway at large.

Manchester Railway. (See Fig. 1.) The L&M was neither the world’s first railway, the first to carry passengers, nor the first to use steam-powered locomotives. But it represents the first incarnation of the railway in its modern form: driven entirely by steam locomotive, connecting crucial industrial cities, and captivating a fascinated, even anxious public. The L&M’s immediate commercial success helped to invigorate the financial speculations and railway construction projects whose economic, physical, and cultural consequences were epochal. For so many observers who witnessed it or who read the widespread reports, the opening of this line inaugurated the railway era for better and worse. Its public commencement tracks the spectrum of attitudes—from celebrations of its commercial potency to astonishment at the experience of traveling at high speed (25 miles per hour!) to shocked apprehension of its serious dangers—that would come to characterize the railway at large.

Figure 1: Opening of the Liverpool & Manchester Railway, 15 September 1830. Drawn and engraved by Isaac Shaw Junior, published 1831. Used with permission. Copyright (c) National Railway Museum / Science & Society Picture Library

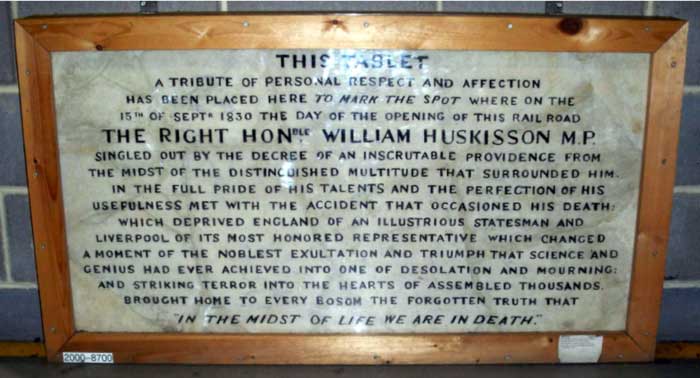

The opening was a massive publicity event orchestrated by the Liverpool and Manchester Railway Company and its investors. But the celebrations were marred by a fatal accident to the Liverpool MP William Huskisson (Fig. 2), who, at a stopping point midway through the journey, had fallen onto the tracks. An oncoming train brutally crushed Huskisson’s leg;

Figure 2: William Huskisson, English politician, c 1820s. Mezzotint by Thomas Hodges, published 1832. Used with permission. Copyright (c) Science Museum / Science & Society Picture Library

It is impossible to figure to one’s self any event which could produce a greater sensation or be more striking to the imagination than this, happening at such a time and under such circumstances: the eminence of the man, the sudden conversion of a scene of gaiety and splendour into one of horror and dismay; the countless multitudes present and the effect upon them . . . all calculated to produce a deep and awful impression. (42)

The opening of the L&M railway was staged as a promotional “event” by its directors, but the day’s tragic turns and fascinating political contrasts make this an event of much greater significance. It produced deep impressions on its time, and reactions to it express the complexities of its cultural-historical moment. During the pivotal years between the Peterloo Massacre (1819) and the First Reform Bill (1832), the opening plays out conflicts between England’s landed interests, a rising middle class of industrialists, and the laborers and reformers caught up in the era’s sweeping changes.

The event also contributes to a genealogy of the railway and the industrializing, interconnected era it spurred. The L&M railway was conceived by industrialists and commercial parties who were drawn to its potentials for lowering costs, decreasing time of transport, and efficiently moving freight. Transporting people was not a major focus in the original proposal, even though within five years of its opening the L&M was moving half a million persons per year and passenger traffic comprised the bulk of its profits. Instead, the company aimed to create a crucial link in the industrial infrastructure of England’s north, connecting Liverpool, a harbor for import and export, with Manchester, the country’s most conspicuous manufacturing and industrial center. (See Fig. 3.) Steam already powered the engines driving the revolution in manufacturing; it would soon similarly transform the transport network of industrial materials, finished goods, persons, and printed information. Conceived as part of the infrastructure of industrial capitalism, the L&M like so many railways was funded through capital speculations (in the “railway mania” of the 1840s, speculative investments in new railway projects amounted to a stock market bubble). The railway was integral in shaping the material exchanges as well as the abstracted financial transactions of Britain’s modernizing capital economy.

Figure 4: The Remains of Stephenson’s ‘Rocket’, 1829. Used with permission. Copyright (c) National Railway Museum / Science & Society Picture Library

Figure 5: View of the Railway across Chat Moss. Engraving by Henry Pyall. This image is in the public domain in the United States because its copyright has expired.

The construction of the L&M’s trackway faced significant engineering challenges, requiring the construction of multiple bridges and viaducts, the carving of two miles of rock out of the Olive Mount (Figs. 6 and 7), and the seemingly impossible crossing of a four-mile peat bog called Chat Moss (Fig. 5). These challenges were solved thanks to engineering ingenuity and a small army of laborers called “navvies” (short for “navigators,” a term for canal workers), whose unnamed contributions to the railway are often eclipsed by histories of hero-engineers like George Stephenson and the Great Western Railway’s Isambard Kingdom Brunel. Railway construction also met with significant human obstacles in the form of protests and even violent resistance. Railway surveying became a battleground for pastoral resistance to the incursions of industry, a struggle that typically pitched liberal, pro-growth politics against more conservative entrenchments of aristocratic rural landowners as well as workers anxious about their threatened jobs.[2] During the planning of the L&M (as with other early railways), surveyors were sometimes fiercely opposed by property holders and agricultural tenants, a mix of protectionist propertied interests and laborers averse to mechanization. These confrontations could turn violent. In one instance, an L&M surveyor’s theodolite was smashed by an angry rural crowd throwing rocks at equipment and crew alike. Subsequently, the L&M’s surveyors returned by moonlight, using distant gunshots as a decoy while they completed their hasty measurements (Smiles 156).

Figure 6 (left): Excavation of Olive Mount, 1833. This image is in the public domain in the United States because its copyright has expired. Figure 7 (right): “Sketch of the Bridges and Excavation of Olive Mount,” 1832. Coloured lithograph drawn and engraved by William Smoult. Used with permission. Copyright (c) National Railway Museum / Science & Society Picture Library

But the L&M was built and its signature engine, the “Rocket,” was soon unleashed upon it. Its significance was immediately apparent to contemporaries, such as the builder and surveyor William James: “Here is an engine that will, before long, effect a complete revolution in society. . . . It is the greatest wonder of the age, and the forerunner, as I firmly believe, of the most important changes in the internal communications of this kingdom” (qtd. in Smiles 149). Its debut on 15 September 1830, along with seven other L&M engines at the grand opening, provoked similarly awed reactions from observers first encountering these machines and first experiencing their unprecedented velocity. The lead engine, the Northumberland, was piloted by the company’s chief engineer, George Stephenson, and pulled a decorated carriage with a cortege of dignitaries including the prime minister (Arthur Wellesley, Duke of Wellington) and secretary of state (Robert Peel). The other engines pulled carriages with hundreds of passengers, including other VIPs and a large cohort of reporters.

Figure 8: Programme for the opening of the Liverpool & Manchester Railway, 1830. Used with permission. Copyright (c) National Railway Museum / Science & Society Picture Library

Stanley claims that “winged words, written with running pens” are best adapted to the new era and its rushing engines, signaling the stylistic experiments of descriptions of the railway to come, such as Charles Dickens’s wonderful 1851 Household Words essay “A Flight.” Other commenters and authors, including George Eliot, would decry railway travel for annihilating any verbal or narrative representation at all. In the beginning of Felix Holt, the narrator celebrates “the slow old-fashioned way of getting from one end of our country to the other” as opposed to a railway journey, which “can never lend much to picture and narrative; it is as barren as an exclamatory O!” (5). Instead, the narrator praises a jocular coach driver for his intimate knowledge of places on the journey. The coachman brims with stories and anecdotes about local color. Concerned for his job as much as for the fate of narrative, this driver is no fan of trains: “the recent initiation of railways had embittered him: he now, as in a perpetual vision, saw the ruined country strewn with shattered limbs, and regarded Mr Huskisson’s death as a proof of God’s anger against Stephenson” (9). Felix Holt was published in 1866, but the death of Huskisson had become a recurring memory of cultural trauma. The coachman’s nightmare also suggests one of several ways that the tragic event was interpreted. From his perspective, it represents providential retribution. But the accident tells other stories, too, about interesting moments of contact between cultural and political realms.

The news of Huskisson’s accident came to dominate reports of the opening of the L&M railway. The first report from the Times gives a good sense of how, for all the pomp, circumstance, and technical wonders on display, the accident to Huskisson became the day’s defining event. The correspondent writes:

I had intended to give you some faint description of this astounding work of art, of the crowds which have lined almost every inch of our road, of the flags and banners, and booths and scaffoldings, and gorgeous tents . . . [but I will] defer that description as comparatively uninteresting, owing to the fatal accident (as I apprehend) that has befallen Mr. Huskisson. (“Dreadful Accident To Mr. Huskisson” 3)

With the accident, the tone of the event radically shifts from celebratory to funereal. The grand orchestrations become “uninteresting” in light of Huskisson’s injuries. It seemed that the L&M was headed for a modern public relations disaster. But in fact, Huskisson’s accident had made the opening of the L&M into hard news, bringing “the opening of the railway to a far wider audience than would have otherwise observed it” (Garfield 180). While his death seemed like a judgment on the railway to some, to others it drew attention to the power and spectacle of a mode of transport that, notwithstanding its apparent dangers, would change the world.

What had happened was this: near the middle of the journey, all the engines stopped to take on water at Parkside Station (now gone). Huskisson joined dozens of people who left the carriages to stretch their legs and inspect the trains. Huskisson also saw a political opportunity to approach the Duke at his window. They shook hands and exchanged a few friendly words. But warnings were shouted as the Rocket started moving past on the neighboring track. Everyone managed to get out of the way, but Huskisson, clinging to the door of the Duke’s carriage, fell to the rails and his leg was severely lacerated beneath the oncoming engine. The Duke ceded his train to the critically injured man who was immediately taken, with his wife, to nearby Eccles for medical attention. Huskisson died later that evening.

There are two crucial moments of contact here: human with machine and also Huskisson with the Duke. Their fateful handshake was a moment of reconciliation, a temporary bridge between the political cultures that the journey as a whole would span. The men were political rivals. The Duke, as prime minster, led the arch Tories whose support derived from landed interests and the church. Huskisson led a faction of liberal Tories who supported Catholic emancipation, free trade, and some expansion of the vote, earning support from the middle classes. Relations between Huskisson and the Duke had been cool after Huskisson’s failed cabinet appointment and vote against the government for better political representation in Manchester (Smiles 224; Howe). But Huskisson wanted back in, and the Duke, noting Huskisson’s local popularity, may have seen an opportunity to shore up his own declining status. The memory of the Peterloo Massacre was still fresh; anger was mounting about the “bread tax” or grain tariffs called the Corn Laws, which protected English landowners at the expense of the poor (see Ayşe Çelikkol, “On the Repeal of the Corn Laws, 1846″); pressure was increasing among the working and middle classes for parliamentary reform and expanded rights to vote. The L&M’s own route revealed such disparity in political representation: along its way, the tiny town of Newton had two members of parliament, while at its terminus, the rapidly growing city of Manchester had none (Garfield 32). The handshake and its traumatic breakage plays out in microcosm the tumultuous political dynamics of the years leading up to the Reform Bill of 1832. Near the journey’s midpoint, the handshake marks a political junction, an equilibrium between the celebrations at Liverpool and protests they would soon encounter. Huskisson was no radical seeking widespread expansion of the vote, but his accident added macabre poignancy to what awaited the Duke at the Manchester terminus.

After Huskisson’s broken body was sped away, the Duke did not want the procession to continue. Celebrations no longer seemed appropriate. But the L&M’s directors (and much of the public) strongly urged that the trains finish the journey. Civic officials who arrived from Manchester strengthened the case. The mood of the waiting crowd was worsening; the engines should finish “to prevent the tranquility of Manchester from being endangered” and stave off riots. The directors also needed “to show the public that the accident was a mere accident”—i.e. regrettable human error, but not a fault of the machinery (“Dreadful Accident To Mr. Huskisson” 3). Fearing for their railway’s reputation and financial future, they argued for public duty and political stability. The Duke relented and the procession continued, slowly and without festivity. The crowds at Manchester were huge: “as far as the eye could reach . . . was one vast sea of people” (Stanley 827). As the Times reported, that crowd mingled cheers with jeers and political messages aimed specifically at the Duke, such as banners with the slogans “Vote by Ballot” and “No Corn Laws!” as well as several tricolor flags adapted from the French and symbolic of revolution. Weavers, angry with their ongoing displacement by industrial machinery, reportedly threw stones at the trains. Here, the journey reached the endpoint of its political spectrum. The industrial boomtown was a stronghold for political reformers who made their position clear to the arch Tory prime minster. Fortunately for the Duke, no violence came to pass and the trains were turned for their lugubrious trip back to Liverpool.

The return trip was like a funeral procession, depressed by the heavy irony of Huskisson’s accident, the unwelcome reception in Manchester, and multiple mechanical problems. At one point, several engines could not even make it up an incline, so the men got out to walk beside the laboring trains. On foot, Stanley noted the engines’ sparks, steam, and raining ash on the darkened landscape, “a strange but sombre illumination” and backdrop to the “utter uncertainty” people were feeling about the day (830). It seemed like an inauspicious start for the L&M if not the railway age itself. The day it was triumphantly born concluded with the ironic death of one of its ardent supporters. Its high-profile public celebration ended in sharp political critique. Its orderly proceedings gave way to a state of alarm and fatigue.

Others would interpret the day’s events and consequences differently. For example, an early biography of George Stephenson noted that, as he drove the Northumbrian engine away with “the wounded body of the unfortunate gentleman,” he set a world record for speed, achieving “the rate of thirty-six miles an hour. This incredible speed burst upon the world with the effect of a new and unlooked-for phenomenon” (Smiles 224). According to this writer, regardless of its unfortunate speed bumps, the L&M was a decisive commercial and engineering success, a harbinger of the “new” era apprehended by so many. Alongside the tracks the vast celebratory crowds remained, unaware of the accident, and “waved heartily as the calamity rattled past” (Garfield 161).

Figure 9: Memorial tablet placed near the site of Huskisson’s accident, now in the National Railway Museum. Photograph by Flickr user Bolckow, 2007. Creative Commons license BY-NC-SA 2.0.

Huskisson was buried in a Liverpool church though a memorial was constructed near the scene of his fatal accident. Its central tablet explains that his accident “changed a moment of the noblest exultation and triumph that science and genius had ever achieved into one of desolation and mourning.” On the other hand, the accident changed nothing. A coroners’ jury had declared a verdict of “accidental death,” acquitting the railway company, machinery, and operators of all blame and reassuring people that Huskisson’s accident was unique, the result of regrettable human error (Garfield 177, 188).

Figure 10: Replica of the “Rocket” in the National Railway Museum. Photograph by Flickr user oalfonso, 2009. Creative Commons license BY-NC-SA 2.0

HOW TO CITE THIS BRANCH ENTRY (MLA format)

published December 2012

Fyfe, Paul. “On the Opening of the Liverpool and Manchester Railway, 1830.” BRANCH: Britain, Representation and Nineteenth-Century History. Ed. Dino Franco Felluga. Extension of Romanticism and Victorianism on the Net. Web. [Here, add your last date of access to BRANCH].

WORKS CITED

Daly, Nicholas. “Railway Novels: Sensation Fiction and the Modernization of the Senses.” ELH 66.2 (1999): 461-487. Print.

Dickens, Charles. “A Flight.” Household Words 30 Aug. 1851: 529-533. Print.

“Dreadful Accident To Mr. Huskisson.” The Times 17 Sep. 1830: 3. Print.

Eliot, George. Felix Holt, the Radical. Ed. Fred C. Thomson. Oxford: Clarendon, 1980. Print.

Freeman, Michael J. Railways and the Victorian Imagination. New Haven: Yale UP, 1999. Print.

Garfield, Simon. The Last Journey of William Huskisson. London: Faber, 2002. Print.

Greville, Charles C. F. The Greville Memoirs. 2nd ed. Ed. Henry Reeve. London: Longmans, Green, and Co., 1874. Print.

Harrington, Ralph. “Representing the Victorian Railway: The Aesthetics of Ambivalence.” Dr Ralph Harrington’s Miscellany. WordPress, 2006. Web. 4 Aug. 2011.

Howe, A. C. “Huskisson, William (1770-1830).” Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. Oxford UP, 2004. Web. 23 May 2012.

Matus, Jill L. “Trauma, Memory, and Railway Disaster: The Dickensian Connection.” Victorian Studies 43.3 (2001): 413-436. Print.

Schivelbusch, Wolfgang. The Railway Journey: The Industrialization of Time and Space in the 19th Century. Berkeley: U of California P, 1986. Print.

Simmons, Jack. The Victorian Railway. New York: Thames and Hudson, 1991. Print.

Sinnema, Peter W. “Representing the Railway: Train Accidents and Trauma in the Illustrated London News.” Victorian Periodicals Review 31.2 (1998): 142-168. Print.

Smiles, Samuel. The Story of the Life of George Stephenson, Railway Engineer: Abridged by the Author from the Original and Larger Work. London: J. Murray, 1859. Google Book Search. Web. 31 Oct. 2012. <http://books.google.com/books?id=VZlEAAAAIAAJ>.

Stanley, Rev. Edward. “Opening of the Liverpool and Manchester Railroad.” Blackwood’s Edinburgh Magazine 28 (1830): 823–830. Print.

Wells, H.G. Anticipations of the Reactions of Mechanical and Scientific Progress Upon Human Life and Thought. London: Chapman & Hall, 1902. Print.

RELATED BRANCH ARTICLES

Nancy Rose Marshall, “On William Powell Frith’s Railway Station, April 1862″

ENDNOTES

[1] There are many excellent sources in tracking the railway’s perceptual, cultural, and specifically literary effects. See Schivelbusch, Simmons, Harrington, and Freeman for wide-ranging surveys with rich examples. Other scholars, including Sinnema, Daly, and Matus, look more closely at how the shocks of railway travel reshaped the senses and styles of textual representation.

[2] For background and more sources on this conflict and its abiding rhetoric, see the chapter “The Railways’ Vandalism” in Simmons (155-173).