Abstract

Augusta Webster’s service on the third London School Board 1879-1882 was preceded by a campaign fraught with attempts to deter her from proceeding through the election process. Mentored in August of 1879 by Helen Taylor, the stepdaughter of John Stuart Mill, Webster successfully attained a seat on the Board despite a male consortium of Board members determined to exclude women from this form of public office. The intrigue against her unfolds in the press and in correspondence archived in the Mill Taylor Collection at the London School of Economics. These documents reveal attempts to make her step down as a candidate in order to allow the four men of the previous Board to continue as a consortium for the district of Chelsea. She was accused of selfish ambition, of costing the district money that would be wasted when her inevitable defeat came about, and of impeding the work that could only be done effectively by men. Her success in this election and in the election of 1885 did not mitigate similar problems when she ran for a seat on the Board for the third time in 1888. Women candidates for Board seats were fewer in number than male candidates, and, it is hinted in the press, she failed to retain her seat as a result of her determination to improve the education available to girls and the salaries of women teachers and teaching assistants.

When Augusta Webster decided to run for election to the London School Board in 1879, she was a well-respected literary figure with a long record of service to the London Suffrage Society. She served on the third London School Board 1879-1882 and on the fifth Board 1885-1888; she withdrew from elections to the fourth Board due to ill health, and she lost the election to the sixth Board. Webster viewed education as the key to the preparation of women to obtain a share of the patriarchal power pie, and, once she had won a seat on the London School Board, she worked consistently in pressing for the educational rights of women and girls. Webster’s competent work on the Board is a matter of record; however, the electoral process through which she won her seat and eventually lost it is a record worth reconstructing, for it tells us a great deal not only about Webster’s determination and perseverance but also about the gender politics at work during one of the earliest franchises in which British women could participate as candidates and as electors. One of her Board colleagues, John Lobb, immortalized Webster to a reporter for the West Middlesex Advertiser during the 1888 elections as “a dear, motherly body, eager to do good, with a kind heart as well as a clear head” (5).[1] While Lobb’s intent seems complimentary, his choice of words foregrounds Webster’s gender, casting her Board service in terms that imply that she belongs in a domestic as much as in a civic space. Taken in the context of the enduring nature of the patriarchal system within which the London School Board elections took place and the fact that Webster was then failing in the polls, his remarks were no doubt more damaging than helpful. It was precisely the assumption of masculine superiority in public life that threatened to derail Webster’s candidacy in the electoral process of 1879, when Helen Taylor, the stepdaughter of the iconic male supporter of universal suffrage, John Stuart Mill, and a fellow Suffrage Society member, mentored Webster through a difficult course as she fought a male consortium of Board members for the right to run for and hold public office.

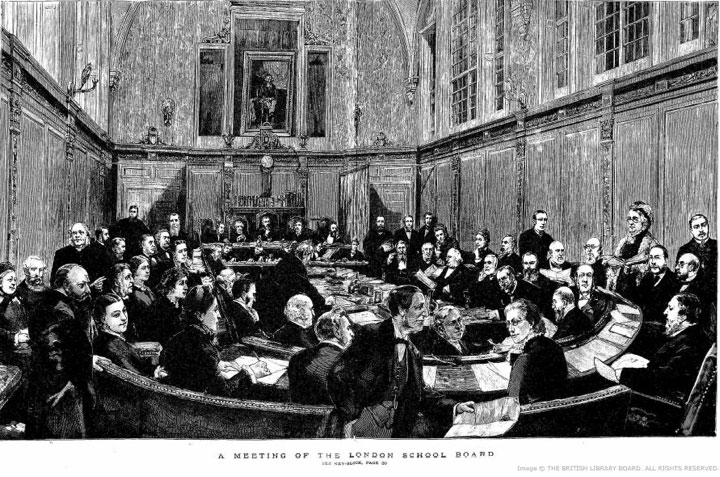

Figure 1: A Meeting of the London School Board (Helen Taylor is the first woman in the second row seated to the left of the gentleman standing centred in the foreground. Webster is seated in the same row, in the fourth seat to the left of Taylor. Photo courtesy of the _Graphic_, and identification thanks to Jane Martin)

Webster’s difficulties in attaining a seat on the London School Board are not surprising as we view the campaign in retrospect, and seemed not to surprise Webster, who was well prepared for such opposition from the moment she declared her intentions at a meeting of the Central Auxiliary Committee for promoting the candidature of women for the London School Board (“Women on the School Board” 118). The circumstances of Webster’s agreeing to run for a seat on the Board, then, suggest that she and Taylor, also in attendance at the meeting, were ready to press for an answer to the “Woman Question.” This moniker had already been expanded to include issues beyond parliamentary suffrage, and those offering to run would certainly have anticipated the patriarchal context of this campaign and the depths of resistance to gender equality. The process that the election followed also points to the reasons behind the inordinately long time it took for women to gain full constitutional rights.

London School Board Records and the two newspapers devoted to education and to reporting on London School Board meetings, The Schoolmaster and The School Board Chronicle, quote exchanges between Board members directly and reveal the gendered political climate of Board matters. These records provide context not only for the climate within which Webster was working while on the Board but also for the issues on which her campaign for election was based. For instance, toward the end of her term in July 1888, just before she began her final campaign, Webster urged that changes be made to the curriculum for girls, who were compelled to enroll in Domestic Science, later renamed Home Economics, while boys studied Mathematics. As the School Board Chronicle reports 13 October 1888, Webster simply recast the problem in terms her male colleagues could understand, appropriating the rhetoric of the domestic space to which girls were relegated and arguing that girls should be permitted to study Mathematics as a means of enhancing their ability to measure correctly and navigate their way through complex patterns when dressmaking. In presenting her argument in these terms, she thereby implicitly suggested that since they were engaged already in such activities, girls were perfectly capable of succeeding at Mathematics (362). Webster had already addressed another vexing issue using this strategy on 23 June 1888 when the Board discussed whether married women should remain barred from becoming teachers. Contrary to some of her board colleagues, Webster argued that married women should be hired because their experience as mothers made them ideal educators (Schoolmaster 880). Her emphasis on women’s issues—education curricula and salaries for female teachers—was controversial in a climate of increasingly limited resources and what was perceived to be an erosion of masculine power by women’s involvement in policy-making. From her commitment to run in the 1879 elections, throughout her service, and until her final defeat in 1888, Webster faced male consortia and coalitions that worked with the express purpose of excluding women from policy-making and policy-implementation in matters of education.

Webster found herself running for election to the London School Board in a climate of gendered politics and military metaphors that characterized her in terms of “attacking” a male bastion of power. An editorial note in The Schoolmaster on 18 October 1879 laments that the presence of female candidates was orchestrated in military fashion to “storm each of the ten divisions in the interest of women’s rights, the aim being to secure the return of at least one lady in each, and as many as practicable” (421). Of course, this claim of a plan to further the cause of women’s suffrage was true, and the rhetoric of war and invasion indicates the extent of male fears that women candidates for the London School Board would influence not only the availability of education for women but also the direction in which educational policy would move in these respects. Increased numbers of educated women in public life would inevitably erode the patriarchal socio-political system already weakening in the late nineteenth century.

Webster’s borough of ![]() Chelsea was made up of four parishes, Chelsea,

Chelsea was made up of four parishes, Chelsea, ![]() Fulham, Hammersmith, and

Fulham, Hammersmith, and ![]() Kensington, with a total representation of four seats on the London School Board. In the previous Board 1876-1879, the Chelsea seats had been held by Joseph Firth, John Hall Gladstone, Charles Darby Reade, and Robert Freeman. Pressure to have Webster step aside to ensure that these four men would continue on the next Board began on 13 August 1879 with an anonymous letter to the editor of the Echo from “An “Elector” that remains as an undated news cutting now held in the Mill Taylor Collection. The Echo was a community newspaper with a readership much broader than the newspapers specifically focused on school Board issues. The author of this letter, who soon identified himself to Webster as Joseph Beal, named her as a threat to a politically powerful coalition of the four men who had served well together on the previous Board and who had been “promised joint support” at a “public meeting recently held in

Kensington, with a total representation of four seats on the London School Board. In the previous Board 1876-1879, the Chelsea seats had been held by Joseph Firth, John Hall Gladstone, Charles Darby Reade, and Robert Freeman. Pressure to have Webster step aside to ensure that these four men would continue on the next Board began on 13 August 1879 with an anonymous letter to the editor of the Echo from “An “Elector” that remains as an undated news cutting now held in the Mill Taylor Collection. The Echo was a community newspaper with a readership much broader than the newspapers specifically focused on school Board issues. The author of this letter, who soon identified himself to Webster as Joseph Beal, named her as a threat to a politically powerful coalition of the four men who had served well together on the previous Board and who had been “promised joint support” at a “public meeting recently held in ![]() Hammersmith.” Beal suggests, without explaining his reasoning, that since the seats of Reade, Freeman, and Gladstone were “absolutely unassailable,” the seat “to be attacked” must be that of Firth. The reason for this “assumption” became clear over the next few days when Webster learned that Firth, who was actually the strongest candidate going into the election, had made known his intention to step down and retire. His resignation would leave an opening through which Webster seemed poised to move, and clearly Beal and others considered her to be a strong candidate.

Hammersmith.” Beal suggests, without explaining his reasoning, that since the seats of Reade, Freeman, and Gladstone were “absolutely unassailable,” the seat “to be attacked” must be that of Firth. The reason for this “assumption” became clear over the next few days when Webster learned that Firth, who was actually the strongest candidate going into the election, had made known his intention to step down and retire. His resignation would leave an opening through which Webster seemed poised to move, and clearly Beal and others considered her to be a strong candidate.

Beal wrote directly to Webster on 8 August 1879 to tell her that “a great mistake is being committed” in her persistence in running for election, and that she was “imperiling the seat of one of the most valuable members of the Board, without the possibility of doing his work for some time.” Webster responded in a letter sent to Taylor on 11 August by correcting Beal’s grammar: “The ‘for some time’ is squeezed in as an after thought after the completed sentence, as I have put it. I take it to mean the work which Mr. Firth would do for some time,” she tells Taylor with humor. Webster wrote her own letter to the editor of the Echo to answer Beal publicly, although, as she told Taylor on 11 August, Beal “is a power with the Echo, and my letter will probably not be inserted.” In her letter to the editor, Webster reiterates that she aims to “attack” no one, that she “consented to stand, because [she] share[s] the widespread opinion that there ought to be more women than four on a Board of fifty, who arrange the education of girls, and also of boys, in infant years, and who undertake the visiting supervision of a multitude of young female teachers.” Furthermore, she points out, it is not the case that “the School Board division of Chelsea is the private reserve of the four out-going members, to be dealt with at their joint pleasure, each to hold his seat or give it away as may be decided.”

Her letter did appear in the Echo, and elicited Beal’s predictable response as “An Elector” on 13 August, as he tries to situate her determination once more in terms of gender:

The demand for more women on the Board on which she bases her candidature is not a popular demand. There is a very strong adverse opinion, and, perhaps stronger in the Board than elsewhere, that women members are a failure. As visitors, no doubt, they could do good work, but on the Board more work in direct popular lines for women is done by men like Mr. Firth than by the women. (2)

Beal warns that she cannot win because her “support would come from nonordinary people” rather than “the clubs, the moving power in the division.” Then in a postscript, he suggests with an astonishing lack of logic after these shots of the patriarchal cannon that if she were determined to run, she could run elsewhere, in ![]() Westminster, for instance, where there were four open seats. In response to Beal’s desire to meet with her and her friends to discuss, as he put it, “the propriety” of her candidature, she stood her ground and wrote to him on 9 August 1879 that if he wanted to see her, she would be “at home” the next day, but she did not offer to call on him. The ensuing exchanges suggest that he did not accept the invitation.

Westminster, for instance, where there were four open seats. In response to Beal’s desire to meet with her and her friends to discuss, as he put it, “the propriety” of her candidature, she stood her ground and wrote to him on 9 August 1879 that if he wanted to see her, she would be “at home” the next day, but she did not offer to call on him. The ensuing exchanges suggest that he did not accept the invitation.

By 6 September, Beal had become increasingly belligerent and personal, ending all pretence of general concerns. Webster’s continued commitment to run for a place on the Board will cost a great deal of money, about ₤1,000, he writes, again waging war in the Echo. Webster “thinks more of her personal ambition than of school Board work,” he accuses, and he warns that should she refuse to step away “from a field already appropriately occupied” he and his friends will ensure that her candidacy is thoroughly challenged (1). In her exchanges through the Echo and directly to Beal, Webster is clear that she is well aware that it is not really Firth whom Beal wants to protect, but someone else. As Webster had already pointed out in her letter to the editor of Echo on 12 August, Firth had been returned in the previous election with the strongest number of votes, 13,348, with Freeman winning 10,492, Gladstone 9,942, and Reade 8,222. It would seem that it was Reade who needed protection to ensure the continuance of the male consortium, since the three more popular candidates were more certain of retaining their seats. In falsely naming Firth as the candidate threatened by Webster’s selfish ambition, Beal muddied the water to increase pressure on Webster to step down; he emphasized the danger of her candidacy by using the rhetoric of war and casting her candidacy in terms of “attacking” the most popular representative for Chelsea.

The Firth narrative unfolds as a subtext of Webster’s epistolary duels with Beal. Since Webster refused to withdraw her candidacy, the other members of the consortium prevailed upon Firth to stay in the running. The irony of this situation is that Firth had been supportive of Webster in the early days of the campaign, most significantly by helping her to gain access to the “clubs” to lobby members directly. As she indicates to Beal on 9 August, she had spoken with Firth about her candidacy and he had assured her that “the special work he undertook and for the sake of which he sought election he has brought to completion.” However, Firth quickly became part of the intrigue against her and remained loyal to Beal and his followers. Although he did eventually pull out of the race, at this time he entered the fray between Beal and Webster, writing to her on 9 August that he had “met with leading members of the party” since meeting with her, and had come to the conclusion that “in the interests of the party” he “should not entertain the idea of retiring.” The fact of his staying in the race did not bother Webster at all. Her response to Firth, she told Helen Taylor 11 August, was simply to say that she was “very pleased if he is going on the Board again, sorry if he is not, and thinking the coalition sorry.” However, Webster was disappointed in Firth for attempting to cast this decision as straightforward, with no strings attached, and, as he expressed it to her, “with the one object of securing most certainly the success of these projects which you and I have in common.” Webster inscribed across the bottom of Firth’s letter, “I am half-sick of shadows said the Lady of Shalott,” reflecting her frustration with such equivocating when he had clearly been convinced that he was crucial to the continuance of the male consortium. Like the Lady of Shalott, Webster refused to live in the shadows, and, like the lady, she refused to stay cloistered and obedient, writing herself to the coalition members, Reade, Freeman, and Gladstone, who, she told Taylor on 9 August, still considered her candidacy hypothetical; they “all seem bent on not recognizing that I have come forward” [emphasis Webster’s].

When Webster’s campaign got underway in earnest, she seems to have settled into public speaking with enthusiasm, often having Taylor and other women speakers such as Florence Fenwick Miller appear at her meetings as guest speakers on her behalf. The few remaining letters between Webster and Taylor from the beginning of November until the election indicate that Webster, as the actual election would bear out, was connecting very well with her constituents, particularly the Fulham group. Taylor now became the target in the Echo: in a letter to the editor 21 November 1879 she was accused of planting members in the audience to shout down opposing speakers. Without providing evidence of Taylor’s involvement, E. H. Bayley calls this activity “violence and rowdyism.” Bayley complains that Taylor “impeded the speech of Miss Richardson” and continues in gendered rhetoric, “apart from all other considerations, is it ladylike on the part of Miss Taylor to prevent another lady candidate from being heard by means of such an outrage upon freedom as I have described?” [emphasis Bayley’s]. Webster and Taylor must have been delighted when a Taylor supporter by the name of Mr. H. Pringle wrote to the newspaper 22 November with a rather threatening letter to invoke gender in their favour for a change, suggesting that Bayley might expect censure for this defamation of character not through the legal process but through life being made difficult at his club. Shadows were spreading over the masculine Camelot of patriarchy as well, it seems.

When Webster ultimately won her place on the Board, Gladstone and Freeman were the only members of the original “coalition” to be re-elected: Reade was defeated and replaced by Captain Henry Berkeley, and Firth, whom Webster replaced, had indeed retired. The Daily Telegraph summed up the new Board on 6 December 1879: “We may say that they are, on the whole, decidedly favorable to the friends of the national, compulsory, and unsectarian education” (quoted in The Schoolmaster 620). Taylor was also successfully returned in the election of 1879 and for her final term 1882-1885, after which she retired for health reasons.

An interesting feature of twentieth-century biographical entries on Webster is that they tend to highlight her two successful campaigns and her service on the London School Board without mention of the fact that she did run for and did lose the 1888 election. She came in eighth among eleven candidates vying for five seats. There are no signs either in the press or in the Minutes of the London School Board that she had not preformed competently. Of course, Webster’s defeat may well have been due to the fact that voters simply thought change was in order. However, the other three candidates from the previous Board were all returned. Given the process of the election of 1879, perhaps we can make some conjectures about several elements that may have contributed to her defeat in 1888.

First of all, as the Times reported on 16 November 1888, by this time, the London School Board was less polarized politically, which meant that majority decisions were reached without as much debate as in previous times; consequently, the coalitions and alliances formed on the Board were maintained more easily (10). This unification of the Board tended to work against those trying to further goals less popular with the majority. For instance, Webster’s position that nationally funded education was a necessity and that assistant teachers, who were mainly women, needed a pay raise to ensure equity, went against the views of a Board trying to address public charges of extravagance. In practical terms, it was easier to save money by reducing services to the most vulnerable—the poor and the female segments of the population—the two groups that Webster prioritized in her Board service and in her campaign addresses. There are also indications in the London School Board minutes that Webster was prone to challenge the Chair of the 1885 Board, the Rev. J. R. Diggle. Not only was he a Moderate, while she was a Progressive, but he also tended to stack committees to ensure the success of his own goals, and these goals were by nature exclusive rather than inclusive, favouring causes that Diggle himself championed (Gautry 44). As The Times reported on 16 November 1888, two weeks before election day, the Board under Diggle had agreed to “work to keep out faddists and the persons who seek to obtain seats on the Board with a view, as the Chairman observed, of ‘trotting out’ the discussion of problems with which the Board has nothing to do.” Diggle not only implies that Webster is one of the “faddists” by not naming her in the article but also explicitly asks for “particular support in Chelsea” for “Rev. G. W. Gent, Mr. Denny Urlin, and Mr. G. White; and the Rev. Prebendary Eyton” (10). On Election Day 26 November 1888, the list of members to support was republished, but this time Webster was mentioned in a deliberately negative context: “Mrs. Webster has now been adopted by the radical clubs along with Professor Gladstone, the Rev. C. Leach, Nonconformist, and Mr. Revell” (10).

Finally, the odds were against Webster’s success in a climate of an erosion of female Board members. There had been seven women on the 1882 Board, but Webster was one of only three women serving on the 1885 Board. As the Echo noted 4 November 1885, Webster and the other two female members, Rosamond Davenport Hill representing the City of London and Alice Westlake representing Marlebone, all won with the least number of votes in their districts (2). In the elections of both 1879 and 1885, Webster was the only female candidate for Chelsea, one of five candidates for four seats in 1879 and one of nine candidates for five seats in 1885 (London School Board Election). In 1888, she was one of eleven candidates vying for five seats allotted to Chelsea. While the precise reasons for the fact that fewer women seemed to offer and to succeed in 1888 are not clear, the odds were increasingly against gender equity.[2] The long hours of Board work and the difficult path toward those long hours may well have deterred women from entering into this particular political arena when the issue of female suffrage remained stalled in Parliament until well after the demise of the London School Board in 1904.

How all of these signs pointing to Webster’s defeat came to fruition is indicated in the press that followed the 1888 election. She remained undeterred in articulating her democratic view of Board policy, and she refused to allow the London School Board to save money by disadvantaging women and the poor. Therefore, she continued to support universal education and higher salaries for teaching assistants. In a meeting at ![]() Queen’s Park on 3 November 1888, Webster and two fellow candidates for Chelsea, Gladstone and the Rev. Charles Leach, met with voters. Webster spoke “with great fluency,” reports the West Middlesex Advertizer, providing her listeners with “an interesting exposition of woman’s work on the Board” as she promoted her plans to increase the salaries of school assistants (5). In a second debate held on 12 November at the Chelsea Town Hall, Webster appeared again with Leach, but accompanied this time by another candidate for Chelsea, William Revell. Reporting on this meeting on 17 November, the West Middlesex Advertizer highlights Webster’s reiterated plea for publicly funded education, and her insistence that the current system of having free schools only for those in need created an elitism that would backfire, for “so long as free schools were the exception, and payment of fees the rule, the free schools would sink lower and lower and become ‘sinks of corruption’” (2). Unfortunately, it rained heavily that night and the audience was “thin”; furthermore, Webster, in all probability as the female candidate, spoke first, and, given what seems to have followed, was perhaps placed at a disadvantage in this respect. She made clear that she supported a new school in Chelsea, another unpopular issue when the majority of the Board felt it was more urgently needed elsewhere; moreover, although she had succeeded in getting a school site for Hammersmith, the school itself had not yet been built, she complained and, she continued pointedly, “if the composition of the new Board was similar to that of the last” the plans might sit for another twenty years. Mr. Leach stood up and disagreed with Webster on this point and earned much applause with a “racy and forceful speech,” journalistic reporting that indicates not only the mood at the meeting and but also the position of the newspaper.

Queen’s Park on 3 November 1888, Webster and two fellow candidates for Chelsea, Gladstone and the Rev. Charles Leach, met with voters. Webster spoke “with great fluency,” reports the West Middlesex Advertizer, providing her listeners with “an interesting exposition of woman’s work on the Board” as she promoted her plans to increase the salaries of school assistants (5). In a second debate held on 12 November at the Chelsea Town Hall, Webster appeared again with Leach, but accompanied this time by another candidate for Chelsea, William Revell. Reporting on this meeting on 17 November, the West Middlesex Advertizer highlights Webster’s reiterated plea for publicly funded education, and her insistence that the current system of having free schools only for those in need created an elitism that would backfire, for “so long as free schools were the exception, and payment of fees the rule, the free schools would sink lower and lower and become ‘sinks of corruption’” (2). Unfortunately, it rained heavily that night and the audience was “thin”; furthermore, Webster, in all probability as the female candidate, spoke first, and, given what seems to have followed, was perhaps placed at a disadvantage in this respect. She made clear that she supported a new school in Chelsea, another unpopular issue when the majority of the Board felt it was more urgently needed elsewhere; moreover, although she had succeeded in getting a school site for Hammersmith, the school itself had not yet been built, she complained and, she continued pointedly, “if the composition of the new Board was similar to that of the last” the plans might sit for another twenty years. Mr. Leach stood up and disagreed with Webster on this point and earned much applause with a “racy and forceful speech,” journalistic reporting that indicates not only the mood at the meeting and but also the position of the newspaper.

The Times coverage the day after the election, 27 November 1888, is telling: “in Chelsea, there was a constant stream of voters all day, but the placard information had not generally reached the public, and many people failed to vote, simply because they had not their attention called to the voting places” (10). The misplaced placard information is never explained; however, given the process leading up to this point, one cannot help but feel that it was a strategy of some sort to bring Webster’s public life to an end. The implications of her defeat, of the politics of Board elections, and of decreased numbers of women serving on the Board were soon to be relegated to history, since after the London School Board was dissolved in 1904, matters of education were dealt with by the London County Council and later by London borough councils, thereby ensuring a more democratic and less centralized process of forming educational policy.

published August 2016

HOW TO CITE THIS BRANCH ENTRY (MLA format)

Rigg, Patricia. “Gender and Politics in London School Board Elections: Augusta Webster, Helen Taylor, and a Decade of Electoral Battles.” BRANCH: Britain, Representation and Nineteenth-Century History. Ed. Dino Franco Felluga. Extension of Romanticism and Victorianism on the Net. Web. [Here, add your last date of access to BRANCH].

WORKS CITED

An Elector. “To the Editor.” Echo 13 August 1879: 2. Print

Bayley, E. H. “To the Editor.” Echo 21 November 1879: n. pag. Print.

Beal, Joseph. “To Augusta Webster.” 8 August 1879. MS. Mill Taylor Collection. London School of Economics, London. Print.

—. “To the Editor.” Echo 12 August 1879. 2. Print.

—. “To the Editor.” Echo 6 September 1879. 1. Print.

Betts, Robin. Powerful and Splendid: The London School Board 1870-1904. Cambridge: Tantalon Press, 2015.

Firth, Joseph. “To Augusta Webster.” 9 August 1879. MS. Mill Taylor Collection. London School of Economics, London. Print.

Gautry, Thomas. “Lux Mihi Laus”: School Board Memories. London: Link House Publications, 1937. Print.

Lobb, John. “School Board Elections.” West Middlesex Advertiser 3 November 1888: 5. Print.

—. The London School Board: Twelve Years Experience. London, 1894. Print.

Martin, Jane. “Entering the Public Arena: The Female Members of the London School Board, 1870-1904.” History of Education 22.3 (1993): 225-240. Print.

School Board Records. London Metropolitan Archives, London. Print.

“London School Board Election.” Wikia.com. Web. 11 April 2016.

Pringle, H. “To the Editor.” Echo 22 November 1879: n. pag. Print.

“The London School Board.” The Graphic 8 July 1882: 23. The British Newspaper Archive. Web. 11 April 2016.

The Echo. British Library and London School of Economics. Print.

The School Board Chronicle: An Educational Record and Review. British Library, London. Print.

The Schoolmaster: An Educational Newspaper and Review. British Library, London. Print.

The Times. British Library, London. Print.

Webster, Augusta. “To Helen Taylor.” 9 August 1879. MS. Mill Taylor Collection. London School of Economics, London. Print.

—. “To Helen Taylor.” 11 August 1879. MS. Mill Taylor Collection. London School of Economics, London. Print

—. “To Joseph Beal.” 9 August 1879. MS. Mill Taylor Collection. London School of Economics, London. Print.

—. “To the Editor.” Echo 12 August 1879: n. pag. Print.

West Middlesex Advertizer. British Library. Print.

“Women on the School Board.” Journal of the Women’s Education Union 5 August 1879: 117-119. Print.

ENDNOTES

[1] See Robin Betts, Powerful and Splendid. Betts discusses Lobb and other Board members in a two-volume tome in the context of Board duties. See also John Lobb, The London School Board.

[2] Jane Martin has done extensive work on women on the London School Board. In addition to “Entering the Public Arena” cited here, see “To ‘Blaise the Trail for Women to Follow Along: Sex, Gender, and the Politics of Education on the London School Board, 1870-1904” in Gender and Education 12.2, 165-181; and Women and the Politics of Schooling in Victorian and Edwardian England. London: Leicester UP, 1999.