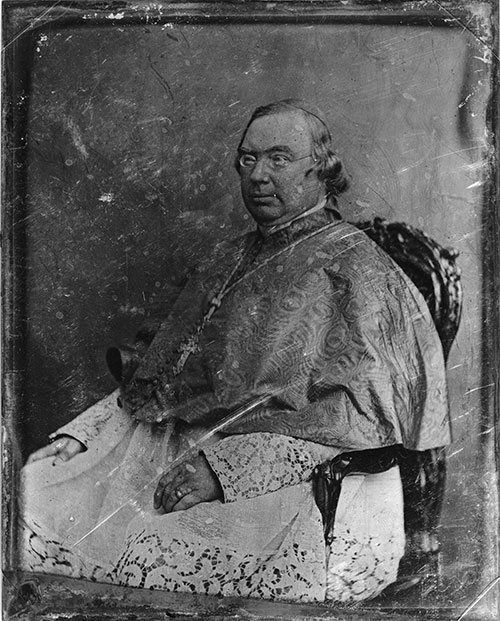

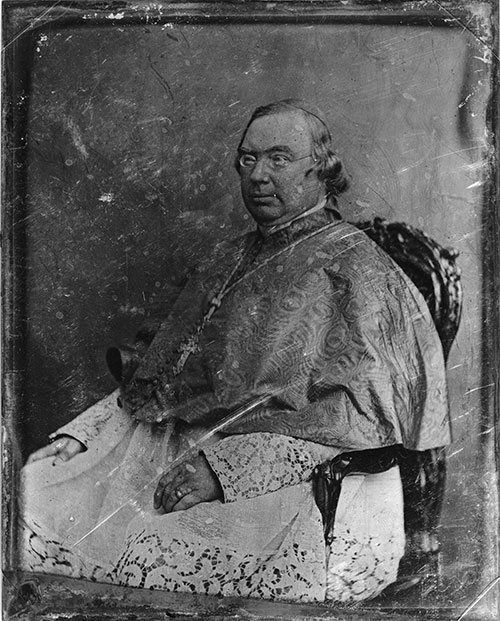

Figure 1: Cardinal Wiseman, daguerreotype by Mathew Brady studio

On 29 September 1850, the Roman Catholic Church in England was set to celebrate an important milestone: Pius IX replaced England’s post-seventeenth-century system of Vicars Apostolic—eight as of 1840—with a fully restored ecclesiastical hierarchy, in line with the system still in place in

Ireland

Ireland. The new hierarchy reestablished the diocesan system with a total of thirteen new sees (including the archbishop’s see at

Westminster

Westminster), each under the control of a bishop. Up to this point, the English branch of the Church had done its best not to stir up any religious or political anxieties over what, despite its considerable symbolic significance, was still at heart a bureaucratic change. Unfortunately, those who favored discretion did not succeed—in fact, quite the contrary. While the turmoil directly related to the new hierarchy died out by 1852, the fallout resonated everywhere from Parliament to popular fiction, and extended to the Church of England itself.

“From without the Flaminian Gate”

Nicholas Wiseman, the newly appointed Cardinal-Archbishop of Westminster, marked the event with a pastoral letter, “From without the Flaminian Gate,” that has gone down in history as a remarkable bit of rhetorical miscalculation. The difficulty was not so much his joy in the restoration of England’s long-lost “religious glory,” but his phrasing of the legal specifics. “So that at present, and until the Holy See shall think fit otherwise to provide,” he explained, “we govern and shall continue to govern, the counties of Middlesex, Hertford and  Essex, as Ordinary thereof, and those of

Essex, as Ordinary thereof, and those of  Surrey,

Surrey,  Sussex, Kent, Berkshire, and

Sussex, Kent, Berkshire, and  Hampshire, with the islands annexed, as Administrator with Ordinary jurisdiction” (“Flaminian Gate” 294). This summary was concise, accurate, and ripe for misinterpretation, and misinterpreted it promptly was. Wiseman meant simply that he was now in charge of the new Catholic dioceses. His Protestant (mis)readers, however, almost uniformly insisted that what he meant was that the Church intended to reclaim the entire country for its own control. “To parcel out the country in territorial divisions,” complained the Berkshire Chronicle, “placing a Romish bishop over each, and to deprive the English church of her legal precedence is only preparatory to the resumption of those claims to universal supremacy, temporal as well as spiritual, which the papacy has never abandoned” (“Notices” 2). This misinterpretation reignited old fears of Catholic subversion and treachery, not least because it threatened to undermine England’s understanding of itself as a country whose liberty from papal control had been guaranteed, first, by the Elizabethan Acts of Supremacy (1558) and Uniformity (1559), which confirmed that the monarch was the head of an established Church of England and mandated weekly attendance at Anglican worship; and, second, the Coronation Oath Act (1688) and the Bill of Rights (1689), which required the monarch to defend the Protestantism of the Church of England and forbade the monarch from either being a Catholic or marrying one. The restored hierarchy merely confirmed long-smoldering doubts about Catholic loyalties. “What do they want!” asked the Rev. Hugh Stowell, indignantly, continuing:

Hampshire, with the islands annexed, as Administrator with Ordinary jurisdiction” (“Flaminian Gate” 294). This summary was concise, accurate, and ripe for misinterpretation, and misinterpreted it promptly was. Wiseman meant simply that he was now in charge of the new Catholic dioceses. His Protestant (mis)readers, however, almost uniformly insisted that what he meant was that the Church intended to reclaim the entire country for its own control. “To parcel out the country in territorial divisions,” complained the Berkshire Chronicle, “placing a Romish bishop over each, and to deprive the English church of her legal precedence is only preparatory to the resumption of those claims to universal supremacy, temporal as well as spiritual, which the papacy has never abandoned” (“Notices” 2). This misinterpretation reignited old fears of Catholic subversion and treachery, not least because it threatened to undermine England’s understanding of itself as a country whose liberty from papal control had been guaranteed, first, by the Elizabethan Acts of Supremacy (1558) and Uniformity (1559), which confirmed that the monarch was the head of an established Church of England and mandated weekly attendance at Anglican worship; and, second, the Coronation Oath Act (1688) and the Bill of Rights (1689), which required the monarch to defend the Protestantism of the Church of England and forbade the monarch from either being a Catholic or marrying one. The restored hierarchy merely confirmed long-smoldering doubts about Catholic loyalties. “What do they want!” asked the Rev. Hugh Stowell, indignantly, continuing:

To make Victoria a Papist, or an exile from her throne. What do they want! To leave us not a vestige of our Protestant Constitution, as settled at the glorious Revolution. What do they want! Not to leave you, Protestant Dissenters, or me, a clergyman of the National Establishment, a right to preach or a right to pray, but as they dictate and enforce. (10)

Although Wiseman quickly tried to clarify the situation, pointing out that the new arrangements pertained “to their own internal organization exclusively” and that “[t]he appointment of a Catholic Hierarchy does not in any way deprive the English Establishment of a single advantage which it now possesses,” it was too late to assuage Protestant fears of an underhanded Catholic conspiracy (An Appeal 4, 17).[1]

Thus, bureaucratic transformation mutated into “papal aggression,” a deliberate assault on both the English people and their Queen. On 7 November, Lord John Russell, the Prime Minister, published an open letter to the Bishop of Durham in the Times that complained of the “assumption of power and “pretension of supremacy” in the Pope’s decision, before going on to denounce the “danger within the gates” posed by Tractarian churchmen (159-60). (As it turned out, the letter crossed paths with a hasty note of explanation from Wiseman that tried to explain the situation [Schiefen 188-89].) Despite the pointedly anti-papal and anti-Wiseman Guy Fawkes celebrations on the fifth of November, the Spectator thought less than two weeks later that the situation was under control, with all “theological combatants” coming to the fray with “no increase of excitement or exacerbation,” and Russell himself duly chastised (“Topics” 1). The Spectator was wrong, although Russell’s cabinet, which now found itself stuck in “one of the longest exercises and political folly and futility that it has been the misfortune of any English government ever to have been engaged in,” would no doubt dearly have liked the Spectator to have been proven right (Larkin 72; cf. Conacher 20).

Wiseman may have staked his claim to Catholicism’s rights on an “appeal to the forum of public opinion, in the name of liberality, over the heads of the politicians who were being untrue to their own liberal principles” (Von Arx 252), but neither the people nor the politicians were especially responsive at the time. In February of 1851, Russell brought in the Ecclesiastical Titles Bill, which criminalized anyone who “should assume or use the name, style, or title of archbishop of any province, bishop of any bishopric, dean of any deanery, in England or Ireland” (“Act” 224). Russell’s speech on the bill came down firmly on the side of those who believed that the Church was claiming a “territorial sovereignty” that directly interfered with that of the Queen (23). But although Russell had consistently been on the Protestant side of any battle regarding the Church of England, he had previously been spending most of his time wrangling with the Tractarians. Now, after years in which his private anti-Catholic sentiments had not overwhelmed his commitment to some measure of toleration, he gave anti-Catholicism official government sanction.[2] Or so it seemed. In fact, after a watered-down version passed in August, the Act was never enforced, much to the fury of the determinedly anti-Catholic Protestant activists whom Russell was trying to placate. Far worse still, the Act’s obvious discriminatory intent angered all the Catholics whom Robert Peel had courted, with some success, just a few years earlier by increasing the annual  Maynooth grant supporting seminaries in Ireland (Kerr 285). As the Catholic novelist Lady Georgiana Fullerton wrote in a letter to her brother, “to see men who pretend to be liberal, act as the Whigs are doing, that makes one indignant, and we might as well appeal to Parliament to protect us against the speeches at Exeter Hall, as for the Legislature to enact penal laws because Cardinal Wiseman and Father Newman hold what to them appears intolerant language” (qtd. in Craven 245).

Maynooth grant supporting seminaries in Ireland (Kerr 285). As the Catholic novelist Lady Georgiana Fullerton wrote in a letter to her brother, “to see men who pretend to be liberal, act as the Whigs are doing, that makes one indignant, and we might as well appeal to Parliament to protect us against the speeches at Exeter Hall, as for the Legislature to enact penal laws because Cardinal Wiseman and Father Newman hold what to them appears intolerant language” (qtd. in Craven 245).

Popular Agitation

There was a well-established tradition of Protestant activist organizations, including the Orange Order (1798), the British Society for Promoting the Principles of the Reformation (1827), the Protestant Association (1835), and the Evangelical Alliance (1845). The Papal Aggression brought many others into being, including the Protestant Defence Committee (1851) and its regional offshoots and the still-extant Scottish Reformation Society (1850 – ) (Paz 32-38; Wallis, Popular Anti-Catholicism 86-101; Wolffe 36-61). Many of these national societies and their regional branches were interdenominational, setting aside confessional differences to preserve a generic Protestantism in the face of what they saw as an explicit Catholic threat. Operating at both national and regional levels, some open to both men and women and others single-sex, these societies engaged in a range of anti-Catholic undertakings: they published journals, newspapers, and tracts; sponsored lectures, debates, and conferences, including debates between Protestant and Catholic clergy; participated in a range of fund-raising activities; judged polemical essay-writing contests; and proselytized both nominal Christians and local Catholics. Notably, the Papal Aggression led to an increase in “Reformation” societies, which saw themselves upholding sixteenth-century British Protestant principles against Roman Catholic depredations. As the very name implies, the Reformation societies grounded their activism in explicitly historical terms: in the words of the Rev. John Cumming, an evangelical Presbyterian who was one of the Victorian era’s loudest voices against Roman Catholicism, “I think that history, especially in tracing out the progress to supremacy of the church of Rome, rises from its lowly position as a mere recorder of the annals of the past, and assumes that lofty aspect and dignity of a prophet giving token that what has been may be, and what once been done, may be successfully tried again” (10). The lesson of history was not that the Reformation had been successfully established on a permanent basis, but that it required ongoing defense against a Church that, given the opportunity, would happily repeat strategies it had employed before.

For anti-Catholic activists, the Papal Aggression controversy was not a frightening rupture in the state of Protestant-Catholic relations, but instead a broader revelation of ongoing Catholic subversion. A striking range of activities and events were identified as signs of ongoing Catholic assault on Protestant liberties, including the  Great Exhibition, which both attracted Catholic visitors and featured a range of Catholic arts (Cantor 27-30, 111-13). The Scottish novelist Catherine Sinclair, one of the first Protestants to respond directly to the controversy in fiction, cast the return of the hierarchy in Beatrice; Or, the Unknown Relatives (1852) as “an Italian flag […] unfurled within the heart of our great metropolis,” an act of imperialist invasion that brings with it a man who “asserts in England now the divine right of Popes,” threatening England’s spiritual as well as its physical territories (37-38). Sinclair’s fears of a Catholic takeover climax at the end with the revelation that another Cardinal is about to set up shop in Edinburgh and Glasgow, suggesting that even Calvinist

Great Exhibition, which both attracted Catholic visitors and featured a range of Catholic arts (Cantor 27-30, 111-13). The Scottish novelist Catherine Sinclair, one of the first Protestants to respond directly to the controversy in fiction, cast the return of the hierarchy in Beatrice; Or, the Unknown Relatives (1852) as “an Italian flag […] unfurled within the heart of our great metropolis,” an act of imperialist invasion that brings with it a man who “asserts in England now the divine right of Popes,” threatening England’s spiritual as well as its physical territories (37-38). Sinclair’s fears of a Catholic takeover climax at the end with the revelation that another Cardinal is about to set up shop in Edinburgh and Glasgow, suggesting that even Calvinist  Scotland is not immune to Catholic incursions. The increasing visibility of the Catholic population, thanks largely to Irish immigration, only heightened Protestant concerns. But while the Aggression thus heightened terrors of Catholicism’s return to power that had already been rehearsed during the debates over Catholic Emancipation (1829), it also augmented, rather than supplanted, activists’ critiques of other Catholic projects, and had the added polemical benefit of a more receptive and wider audience.

Scotland is not immune to Catholic incursions. The increasing visibility of the Catholic population, thanks largely to Irish immigration, only heightened Protestant concerns. But while the Aggression thus heightened terrors of Catholicism’s return to power that had already been rehearsed during the debates over Catholic Emancipation (1829), it also augmented, rather than supplanted, activists’ critiques of other Catholic projects, and had the added polemical benefit of a more receptive and wider audience.

In particular, the controversy spurred new attacks on an old target: the campaign against renewing the Maynooth Grant. The Maynooth Act of 1795 was an ongoing grant, subject to renewal each year, intended to support domestic seminaries in Ireland for Catholic priests, who lost access to European education during the French Revolution. Never popular, the grant became even less so in 1845, when Robert Peel successfully passed a bill to nearly triple the annual grant, from ₤9,000 to ₤26,360, and eliminated the need for it to be renewed by Parliament every year (Wolffe 199). As far as anti-Catholic campaigners were concerned, the Papal Aggression signaled that such concessions to the Catholic interest were deeply wrongheaded (Wallis, “Revival” 531). In the words of the Rev. William Henry Goold, the “reward” for the Maynooth Grant was a violent rejection of everything Protestants held dear: “An attempt at rebellion—a haughty edict from the Flaminian gate—Papal Aggression—the denunciation of their scheme for colleges in Ireland—the establishment of a rival and opposing college by men too poor, forsooth, to oppose Maynooth” (7). For Goold and others like him, the restoration of the hierarchy was proof that Catholics would never be content with any concessions that the government had to offer, short of the nation’s full conversion.

Similarly, parliamentary demands for convent inspections, although not initially successful, played on Protestant fears that Catholics were beguiling, imprisoning, and abusing women, especially women who had been tricked into conversion. Although some French religious houses had taken refuge in England during the French Revolution, by mid-century English and Scottish houses were becoming increasingly visible. The Protestant reaction frequently evoked classic Gothic tropes of convents as sites of erotic frustration (and indulgence), abuse, and murder—tropes on view in high-profile cases such as that of Augusta Talbot (1851), whose stepfather claimed she would be forced to hand over her substantial inheritance to St. Joseph’s Convent, in  Taunton, upon taking her final vows. In 1851, Henry Charles Lacy, along with a more prominently anti-Catholic MP, Richard Spooner, introduced the Bill to Prevent the Forcible Detention of Females in Religious Houses, which called for biannual inspections of religious houses to enable the removal of any unwilling residents, along with fines, transportation, and/or jail time for anyone interfering with the inspectors’ work. After contentious debate, the bill was defeated, but variants reappeared until Charles Newdigate Newdegate finally managed to pass one in 1865, somewhat to everyone’s surprise.[3]

Taunton, upon taking her final vows. In 1851, Henry Charles Lacy, along with a more prominently anti-Catholic MP, Richard Spooner, introduced the Bill to Prevent the Forcible Detention of Females in Religious Houses, which called for biannual inspections of religious houses to enable the removal of any unwilling residents, along with fines, transportation, and/or jail time for anyone interfering with the inspectors’ work. After contentious debate, the bill was defeated, but variants reappeared until Charles Newdigate Newdegate finally managed to pass one in 1865, somewhat to everyone’s surprise.[3]

But, as we have already seen in Russell’s letter to the Bishop of Durham, anti-Catholic agitation was not confined to attacks on the Roman Catholic Church; it also made its impact felt within the Church of England. Indeed, Walter Ralls once suggested that during the controversy, fears of Catholic influence within the Church of England outpaced fears of the Catholic Church itself (247). The Oxford Movement, also known as Tractarianism (for the Tracts for the Times series), had been calling for reforms within the Church since the 1830s, beginning with John Keble’s famous sermon on “National Apostasy” (see Barbara Gelpi, “14 July 1833: John Keble’s Assize Sermon, National Apostasy”): it denounced Erastianism (the belief that the church should be controlled by the state), admired the “unaltered and unblemished precepts of the church fathers,” and critiqued the long-term effects of the Reformation on liturgy, architecture, hermeneutics, and other aspects of Christian practice (Faugh 36). The Tractarians initially maintained an ostensibly anti-Catholic position, insisting that they called for a return to pre-Reformation and Caroline ritual but not for reunion with the Roman Catholic Church; the purpose of their proposed reforms was to show dissatisfied Anglicans that, in turning to “the Prayer Book and the divines of the seventeenth century,” they would discover “grounds to which they could retire for refuge and in which they could find what they had been looking for elsewhere” (Pereiro 58). But opponents saw in them a Catholic fifth column that sought to undermine Anglicanism from within. This antagonistic position was only solidified by the publication of John Henry Newman’s Tract Ninety (1841), which argued that the Thirty-Nine Articles of the Church of England could be read in accordance with Catholic teachings—an attempt to keep Tractarians within the Church that many understood as an excuse for clergymen to lie about their true theological leanings. Nor did it help that a number of high-profile Tractarians ultimately converted to Roman Catholicism, including Newman himself in 1845. For many Protestant opponents, the Oxford Movement was at best a waystation en route to full-blown Catholicism—a “perversion,” in the language of the day—and Tractarian clergy were frequently represented as mere Catholics in disguise. The Papal Aggression thus prompted charges from Evangelical critics like Lord Shaftesbury, as well as from even some of the Tractarians’ previous supporters, that the movement was clearly easing Catholicism into the country through an ecclesiastical back door (Whisenant 23-25; Yates 174-75). Meanwhile, the rise of Anglican convents aroused the same kinds of anxieties about female celibacy, sexual perversion, and mind control that already featured in anti-Catholic convent propaganda. In particular, Priscilla Lydia Sellon, who founded Ascot Priory, one of the first Anglo-Catholic sisterhoods, in 1848, became a lightning rod for controversy—not least in 1852, when a former novice, Diana Campbell, published a wide-ranging attack on her (Mumm 6-7, 194-95).

However, amidst theological controversy, Protestants found ways of linking pleasure and religious politics. Thus, Protestant audiences enjoyed the successful and sometimes scandalous lecture tours of ex-priests like Alessandro Gavazzi, who enjoyed a transatlantic reputation, and Giacinto Achilli, which could feature not only accounts of the horrors of Popery, but also performances of the Mass as a form of theatre (Aspinwall; Paz 26-28, 123-24). Protestants also fed on a diet of anti-Catholic caricature served up by Punch, much to the dismay of the magazine’s Catholic caricaturist Richard Doyle. The cartoons consistently associated figures like Wiseman and Pope Pius IX with beastly invaders and Guy Fawkes, suggesting that the Roman Catholic Church was launching a full-out offensive on England’s political and religious order (Janes 69-74; McNees 21-30). More threateningly to the Catholic population, Protestants paraded and burnt effigies of prominent figures like Wiseman, as they did in Hampshire in 1850 (Matthews 92). And although anti-Catholic fiction was already a well-established genre, authors like Sinclair and the anonymous writer of Fiction but Not Falsehood: A Tale of the Times (1852) used the novel form to articulate Protestant responses to current events. More subtly, W. M. Thackeray’s The History of Henry Esmond (1852), with its semi-competent Jesuit Father Holt, suggested that at least some of the hysteria might have been overblown, as did Jemima Luke Thompson’s ambivalent The Female Jesuit (1851), whose title character is a con-artist (not a Jesuit, dubiously Catholic) who profits from Protestant anti-Catholic stereotypes.

Against “Aggression”: Dissenting and Catholic Responses

Not all Protestants took the hard anti-Catholic line, even those who otherwise opposed the restoration of the hierarchy. Russell’s own cabinet, as we have already seen, was unamused. But that was a question of political survival. Some, like the Congregationalist minister John Angell James, were willing to take the long view: “Let not the Christian then be dismayed at what has taken place,” he mused, “but let him rather look upon it as one of those moral thunder storms, which however awful in its character, alarming in its aspect, and partially destructive in its course, will give us a purer and healthier atmosphere” (9). James’ anxious but more optimistic position reflects the more complex stance taken by Dissenters on the problem. Although, by 1850, Dissenters no longer had to conform to the established Church in order to hold public office, like Catholics they were still subject to legal discrimination on a number of fronts, including taking degrees at  Cambridge. While many Dissenters worried about Catholicism, then, they also understandably tended to “distrust the state” and its willingness to interfere in “the lives of its citizens” (Helmstadter 70-71). As Walter Ralls, Melissa Wilkinson and Timothy Larsen have all reminded us, Dissenting clergymen who disliked Catholicism nevertheless warned against persecuting Catholics themselves. Some Dissenters campaigned in favor of Catholic civil rights, although, as Larsen notes, pro-Catholic opinions in the Dissenting camp became rather wobbly as the Aggression debates wore on (Ralls 248-49; Wilkinson 429, 431-32; Larsen 226-42). And tensions in the ways that Dissenters and Anglicans viewed Catholicism’s potential threat made it difficult for them to collaborate (Paz 127-29). For example, for a number of Dissenters, the problem was not so much Catholicism as the larger question of ecclesiastical government. Thus, the Irish Congregationalist William Urwick carefully pointed out that all the Pope had done was “give a new shape and structure to a body previously existing,” but Urwick nevertheless objected to the new hierarchy on the grounds that it was a hierarchy in the first place (14).

Cambridge. While many Dissenters worried about Catholicism, then, they also understandably tended to “distrust the state” and its willingness to interfere in “the lives of its citizens” (Helmstadter 70-71). As Walter Ralls, Melissa Wilkinson and Timothy Larsen have all reminded us, Dissenting clergymen who disliked Catholicism nevertheless warned against persecuting Catholics themselves. Some Dissenters campaigned in favor of Catholic civil rights, although, as Larsen notes, pro-Catholic opinions in the Dissenting camp became rather wobbly as the Aggression debates wore on (Ralls 248-49; Wilkinson 429, 431-32; Larsen 226-42). And tensions in the ways that Dissenters and Anglicans viewed Catholicism’s potential threat made it difficult for them to collaborate (Paz 127-29). For example, for a number of Dissenters, the problem was not so much Catholicism as the larger question of ecclesiastical government. Thus, the Irish Congregationalist William Urwick carefully pointed out that all the Pope had done was “give a new shape and structure to a body previously existing,” but Urwick nevertheless objected to the new hierarchy on the grounds that it was a hierarchy in the first place (14).

Catholics, obviously, were far more outspoken—although not all of them had been in favor of restoring the hierarchy in the first place, especially some of the “old” Catholic recusant families. Famously, an irritated Duke of  Norfolk promptly became an Anglican (Norman 105). Clergymen, Newman included, preached sermons and issued their own pastorals—sometimes, as in Newman’s case, making matters inadvertently worse (Parsons 148; Paz 96-100; Wheeler 37-46; Wilkinson 432-38). The Dublin Review diagnosed the controversy as a sign that Protestantism had discovered “its own internal hollowness and weakness” and was thus striking out wildly against a Church it perceived to be far stronger (“No-Popery Novels” 145). The more liberal Rambler similarly interpreted the Aggression as a self-inflicted injury for the burgeoning Anglo-Catholic movement, as it demonstrated that everyday Anglicans believed that the Church of England was obviously Erastian at its very foundation (“Rise, Progress” 245). Meanwhile, a satirical rewrite of Russell’s Durham Letter, written in Russell’s voice, drily noted that “[a]s good Protestants, we should be the enemies of all religious liberties—and how can our Catholic fellow-subjects enjoy their religious liberty without the full and free exercise of their religious system?” before going on to pointedly deride the dangers of giving in to the “insane clamour of a barbarous and unchristian fanaticism” (Letter 10, 18). In somewhat more conciliatory fashion, “Sir Charles Rockingham”—actually the Anglo-Gallican diplomat Philippe Ferdinand A. de Rohan-Chabot, Comte de Jarnac—poked fun at Protestant behavior after the Durham Letter in the ironically-titled Cècile; Or, the Pervert (1851), whose eponymous heroine ably defends the Roman Catholic Church against obviously preposterous Protestant attacks; at the same time, the irenic conclusion carefully shows that Catholics merely wanted co-existence, not domination, and that Protestants were just as capable of profound virtue. Meanwhile, in Ireland, Catholics expressed their shock at Russell’s betrayal, although with the exception of Archbishop Daniel Murray, the Irish hierarchy mostly uttered their displeasure behind the scenes (Larkin 86-87). By far the best-known response today, however, is Newman’s Lectures on the Present Position of Catholics in England (1851), which dissected anti-Catholic sentiments with a gimlet eye. Warning his fellow Oratorians that Protestantism’s “ignorance is its strength,” Newman argued that the best way to counter outbursts of anti-Catholic sentiment like the Papal Aggression controversy—which, he noted, was just one more manifestation of a longstanding Protestant attitude—was to “[o]blige men to know you; persuade them, importune them, shame them into knowing you” (372). Catholics could conquer traditional Protestant attitudes only by forcing Protestants to confront the knowledge they so desperately resisted.

Norfolk promptly became an Anglican (Norman 105). Clergymen, Newman included, preached sermons and issued their own pastorals—sometimes, as in Newman’s case, making matters inadvertently worse (Parsons 148; Paz 96-100; Wheeler 37-46; Wilkinson 432-38). The Dublin Review diagnosed the controversy as a sign that Protestantism had discovered “its own internal hollowness and weakness” and was thus striking out wildly against a Church it perceived to be far stronger (“No-Popery Novels” 145). The more liberal Rambler similarly interpreted the Aggression as a self-inflicted injury for the burgeoning Anglo-Catholic movement, as it demonstrated that everyday Anglicans believed that the Church of England was obviously Erastian at its very foundation (“Rise, Progress” 245). Meanwhile, a satirical rewrite of Russell’s Durham Letter, written in Russell’s voice, drily noted that “[a]s good Protestants, we should be the enemies of all religious liberties—and how can our Catholic fellow-subjects enjoy their religious liberty without the full and free exercise of their religious system?” before going on to pointedly deride the dangers of giving in to the “insane clamour of a barbarous and unchristian fanaticism” (Letter 10, 18). In somewhat more conciliatory fashion, “Sir Charles Rockingham”—actually the Anglo-Gallican diplomat Philippe Ferdinand A. de Rohan-Chabot, Comte de Jarnac—poked fun at Protestant behavior after the Durham Letter in the ironically-titled Cècile; Or, the Pervert (1851), whose eponymous heroine ably defends the Roman Catholic Church against obviously preposterous Protestant attacks; at the same time, the irenic conclusion carefully shows that Catholics merely wanted co-existence, not domination, and that Protestants were just as capable of profound virtue. Meanwhile, in Ireland, Catholics expressed their shock at Russell’s betrayal, although with the exception of Archbishop Daniel Murray, the Irish hierarchy mostly uttered their displeasure behind the scenes (Larkin 86-87). By far the best-known response today, however, is Newman’s Lectures on the Present Position of Catholics in England (1851), which dissected anti-Catholic sentiments with a gimlet eye. Warning his fellow Oratorians that Protestantism’s “ignorance is its strength,” Newman argued that the best way to counter outbursts of anti-Catholic sentiment like the Papal Aggression controversy—which, he noted, was just one more manifestation of a longstanding Protestant attitude—was to “[o]blige men to know you; persuade them, importune them, shame them into knowing you” (372). Catholics could conquer traditional Protestant attitudes only by forcing Protestants to confront the knowledge they so desperately resisted.

By the end of the nineteenth century, the High Church novelist Charlotte Yonge could delicately observe that the restoration of the hierarchy “created a sensation now felt to have been disproportionate” and, less delicately, that Russell’s letter had been “foolish” (136). Nevertheless, the Protestant terrors aroused by what had first appeared to be a simple change in Catholic ecclesiastical governance did not ebb quickly, even though outrage at the specific event did. Protestant associations maintained their force throughout the decade, as did anti-Catholic periodicals such as The Bulwark; Or Reformation Journal (1851 – ); meanwhile, authors like Robert Browning (“Bishop Bloughram’s Apology”) joined now-forgotten evangelical novelists in weighing in on the fray. By the end of the decade, however, Anglo-Catholic clergymen like the Rev. Bryan King, a target for riots in 1859, were bearing more and more of the brunt of Protestant suspicions that some skullduggery was at work. The fear that Roman Catholics were plotting an overt takeover could easily give way to the fear that they were plotting a covert one.

published September 2016

Miriam Elizabeth Burstein is Professor of English at the College at Brockport, State University of New York. She is author of Narrating Women’s History in Britain, 1780-1902 (2004) and Victorian Reformations: Historical Fiction and Religious Controversy, 1820-1900 (2013), and editor of Mrs. Humphry Ward’s Robert Elsmere (2013). She is currently working on a new history of religious fiction in nineteenth-century Britain.

HOW TO CITE THIS BRANCH ENTRY (MLA format)

Burstein, Miriam. “The ‘Papal Aggression’ Controversy, 1850-52.” BRANCH: Britain, Representation and Nineteenth-Century History. Ed. Dino Franco Felluga. Extension of Romanticism and Victorianism on the Net. Web. [Here, add your last date of access to BRANCH].

WORKS CITED

“An Act to Prevent the Assumption of Certain Ecclesiastical Titles in Respect of Places in the United Kingdom.” The Law Times 17.490 (6 Sept., 1851): 224. Web. GoogleBooks. 28 August 2016.

Arnstein, Walter. Protestant versus Catholic in Mid-Victorian England: Mr. Newdegate and the Nuns. London: U of Missouri P, 1982. Print.

Aspinwall, Bernard. “Rev. Alessandro Gavazzi (1808-1889) and Scottish Identity: A Chapter in Nineteenth-Century Anti-Catholicism.” Recusant History 28.1 (2006): 129-52. Print.

Cantor, Geoffrey. Religion and the Great Exhibition of 1851. Oxford: Oxford UP, 2011. Print.

Conacher, J. B. “The Politics of the ‘Papal Aggression’ Crisis 1850-1851.” Canadian Catholic Historical Association 26 (1959): 23-29. Print.

Craven, Mrs. Augustus. Life of Lady Georgiana Fullerton. Trans. Henry James Coleridge. 2nd ed. London: Richard Bentley and Son, 1888. Web. GoogleBooks. 28 August 2016.

Cumming, John. Speech of the Reverend John Cumming […] at the Annual Meeting of the Reformation Society, in the Large Room, Exeter Hall, May 2, 1839. London: F. Baisler, 1839. Web. GoogleBooks. 28 August 2016.

Faugh, C. Brad. The Oxford Movement: A Thematic History of the Tractarians and Their Times. University Park, PA: The Pennsylvania State UP, 2003. Print.

Goold, William Henry. Speech Delivered at the Second Annual Meeting of the Scottish Reformation Society, Held in the Music Hall, December 7, 1851. Edinburgh: Johnstone and Hunter, 1852. Web. GoogleBooks. 28 August 2016.

Helmstadter, Richard J. “Some Varieties of Nonconformity.” Religion in Victorian Britain, Vol. IV: Interpretations. Ed. Gerald Parsons. Manchester: Manchester UP, 1988. 61-95. Print.

James, John Angell. The Papal Aggression and Popery Contemplated Religiously. A Pastoral Address to His Flock. London: Hamilton, Adams, & Co.; Birmingham: B. Hudson, 1851. Print.

Janes, Dominic. “The Role of Visual Appearance in Punch’s Early Victorian Satires on Religion.” Victorian Periodicals Review 47.1 (2014): 66-86. Print.

Kerr, Donal A. Peel, Priests and Politics: Sir Robert Peel’s Administration and the Roman Catholic Church in Ireland, 1841-1846. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1982. Print.

Kollar, Rene. A Foreign and Wicked Institution? The Campaign against Convents in Victorian England. Eugene, OR: Pickwick, 2011. Print.

Larkin, Emmet. The Making of the Roman Catholic Church in Ireland, 1850-1860. Chapel Hill: U of North Carolina P, 1980. Print.

Larsen, Timothy. Friends of Religious Equality: Nonconformist Politics in Mid-Victorian England. Woodbridge: Boydell Press, 1999. Print.

Letter from Lord John Russell to the Bishop of Durham. Original Version. Printed from the “Portfeuille Diplomatique”. London: Charles Dolman, 1850. Web. GoogleBooks. 28 August 2016.

McNees, Eleanor. “Punch and the Pope: Three Decades of Anti-Catholic Caricature.” Victorian Periodicals Review 37.1 (2004): 18-45. Print.

Machin, G. I. T. Politics and the Churches in Great Britain 1832 to 1868. Oxford: Oxford UP, 1977. Print.

Matthews, Shirley. “’Second Spring’ and ‘Precious Prejudices’: Catholicism and Anti-Catholicism in Hampshire in the Era of Emancipation.” Evangelicals and Catholics in Nineteenth-Century Ireland. Ed. James H. Murphy. Dublin: Four Courts Press, 2005. 85-96. Print.

Mumm, Susan. Stolen Daughters, Virgin Mothers: Anglican Sisterhoods in Victorian Britain. London: Leicester UP, 1999. Print.

Newman, John Henry. Lectures on the Present Position of Catholics in England. Ed. Andrew Nash. Notre Dame, IN: U of Notre Dame P, 2000. Print.

Nikol, John. “The Oxford Movement in Decline: Lord John Russell and the Tractarians, 1846-1852.” Historical Magazine of the Protestant Episcopal Church 43.4 (1974): 341-357. Print.

“No-Popery Novels.” Dublin Review 31.61 (September 1851): 143-72. Web. GoogleBooks. 28 August 2016.

Norman, Edward. The English Catholic Church in the Nineteenth Century. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1984. Print.

“Notices.” Berkshire Chronicle Saturday 19 October 1850: 2. Web. British Newspaper Archive. 28 August 2016.

Parsons, Gerald. “Victorian Roman Catholicism: Emancipation, Expansion, and Achievement.” Religion in Victorian Britain: Volume I, Traditions. Ed. Gerald Parsons. Manchester: Manchester UP, 1988. 146-83. Print.

Paz, D. G. Popular Anti-Catholicism in Mid-Victorian England. Stanford: Stanford UP, 1992. Print.

Pereiro, James. “Ethos” and the Oxford Movement: At the Heart of Tractarianism. Oxford: Oxford UP, 2008. Print.

Ralls, Walter. “The Papal Aggression of 1850: A Study in Victorian Anti-Catholicism.” Church History 43.2 (1974): 242-56. Print.

“Rise, Progress, and Results of Puseyism.” The Rambler 7.39 (1850): 228-48. Web. GoogleBooks. 28 August 2016.

Russell, John. Papal Aggression. Speech of the Right Honourable Lord John Russell, Delivered in the House of Commons, 7 February, 1851. London: Longman, Brown, Green, and Longmans, 1851. Web. GoogleBooks. 28 August 2016.

—. “Lord John Russell’s Letter to the Bishop of Durham, 1850.” Rpt. in Anti-Catholicism in Victorian England. Ed. E. R. Norman. New York: Barnes and Noble, 1968. 159-61. Print.

Schiefen, Richard L. Nicholas Wiseman and the Transformation of English Catholicism. Shepherdstown: Patmos Press, 1984. Print.

Sinclair, Catherine. Beatrice; Or, the Unknown Relatives. 3 vols. London: Richard Bentley, 1852. Web. GoogleBooks. 28 August 2016.

Stowell, Hugh. The Defences Set Up For the Great Papal Aggression. A Lecture, Delivered at the Beaumont Institution, Mile End Road, on Wednesday Evening, December 11, 1850. London: Royston and Brown, [1850]. Print.

“Topics of the Day.” The Spectator 16 November 1850: 1. Web. GoogleBooks. 28 August 2016.

Urwick, William. A Voice from the Outpost: Two Discourses on the Papal Aggression. Dublin: John Robertson, 1851. Web. GoogleBooks. 28 August 2016.

Von Arx, Jeffrey. “Catholics and Politics.” From Without the Flaminian Gate: 150 Years of Roman Catholicism in England and Wales 1850-2000. Ed. V. Alan McClelland and Michael Hodgetts. London: Darton, Longman and Todd, 1999. 245-71. Print.

Wallis, Frank H. “The Revival of the Anti-Maynooth Campaign in Britain, 1850-52.” Albion 19.4 (1987): 527-47. Print.

—. Popular Anti-Catholicism in Mid-Victorian Britain. Lewiston: Edwin Mellen Press, 1993. Print.

Wheeler, Michael. The Old Enemies: Catholic and Protestant in Nineteenth-Century English Culture. Cambridge: Cambridge UP, 2006. Print.

Whisenant, James C. A Fragile Unity: Anti-Ritualism and the Division of Anglican Evangelicalism in the Nineteenth Century. Bletchley, Milton Keynes: Paternoster, 2003. Print.

Whitehead, Maurice. “Educational Turmoil and Ecclesiastical Strife: The Episcopal Career of Joseph William Hendren, 1848-1853.” Recusant History 25.2 (2001): 263-80. Print.

Wilkinson, Melissa. “Sermons and the Catholic Restoration.” The Oxford Handbook of the British Sermon 1689-1901. Ed. Keith A. Francis and William Gibson. Oxford: Oxford UP, 2012. 428-43. Print.

Wiseman, Nicholas. An Appeal to the Reason and Good Feeling of the English People on the Subject of the Catholic Hierarchy. London: Thomas Richardson and Son, 1850. Web. GoogleBooks. 28 August 2016.

—. “Cardinal Wiseman’s Pastoral announcing the Hierarchy, ‘Out of the Flaminian Gate of Rome.’” Rpt. in Brian Fothergill, Nicholas Wiseman. Garden City, NY: Doubleday, 1963. 293-97. Print.

Wolffe, John. The Protestant Crusade in Great Britain 1829-1860. Oxford: Oxford UP, 1991. Print.

Yates, Nigel. Anglican Ritualism in Victorian Britain 1830-1910. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1999. Print.

Yonge, Charlotte. Life of H. R. H. The Prince Consort. London: W. H. Allen & Co., 1890. Web. GoogleBooks. 28 August 2016.

RELATED ARTICLES

Barbara Charlesworth Gelpi, “14 July 1833: John Keble’s Assize Sermon, National Apostasy”

Laura Mooneyham White, “On Pusey’s Oxford Sermon on the Eucharist, 24 May 1843″

ENDNOTES

[1] Wilkinson notes that Catholic clergymen similarly downplayed any interest in converting England to Catholicism in their sermons on this topic (435).

[2] On Russell’s determinedly Protestant, albeit “Broad Church,” vision of the Church of England’s social role, along with his abandonment of the tolerationist approach, see Machin 196-211, Nikol 343-45. Yates, however, points out that Russell himself attended High Church services clearly influenced by the Tractarians, which even at the time caused some to arch their eyebrows (174).

[3] For the Talbot case, see Whitehead 270-73; and the 1851 bill, Kollar 1-18. On Newdegate’s unending campaigns, see Arnstein.