Abstract

“Darkness” argues that despite their fundamental differences in style, means, and intent, Joseph Conrad’s Heart of Darkness bears the imprint of the author’s early encounter with Harriet Beecher Stowe’s Uncle Tom’s Cabin and that the entanglement of the two narratives is surprisingly rich, extensive, and illuminating. It involves Conrad’s Polish background, class identity, and family and parental engagement in Poland’s revolutionary history and in contemporary issues of rural, ethnically differentiated serf society. It invokes textual resonances, structural parallels, and convergent reception histories. In Tom’s journey upriver to martyrdom in Simon Legree’s nightmare plantation and Marlow’s upriver encounter with Kurtz’s black kingdom, where both the brute and the idealist, isolated and unconstrained, exemplify Absolutist evil, it rises into substantive intertextuality. Indeed, there is quite as much to be gained in reading Stowe through Conrad as the reverse. As foundational texts in the literature of racial injustice and exploitative imperialism, both narratives have come under critical assault and have benefitted from efforts at defensive rehabilitation, these incorporating new perspectives including gender issues—issues implicated in the basic premise of a grounded affinity between Conrad and Stowe’s momentous creations.

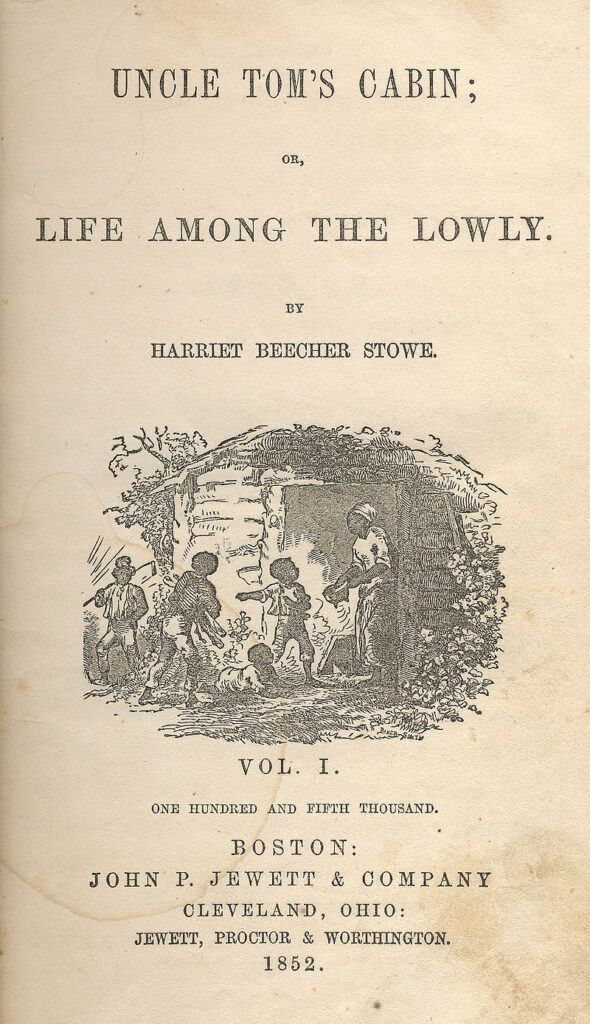

Were the Times Literary Supplement (or its back-page provocateur) to sponsor a contest for the least likely literary bedfellows, Joseph Conrad and Harriet Beecher Stowe would have a fair shot at the laurels. Their literary differences could hardly be more evident, not least in the two works I want to show consorting, Uncle Tom’s Cabin (1852) and Heart of Darkness (1899). They are manifestly at odds, generically, programmatically, and in narrative strategy and its implementation. Generically, Stowe’s blockbuster novel is domestic melodrama crossed with sermon and jeremiad. Conrad’s novella echoes the traveler’s chronicle of adventure and exploration, retelling a challenging odyssey thick with physical hardships and moral perils, all overcome. Stowe’s program is overtly forensic and polemical, rhetorical in the sense that it seeks to impress and persuade. Conrad’s is stubbornly aesthetic; it conspicuously eschews any overt designs on its readers and undermines any portable conclusions on the meaning of its reported and recreated experiences. As to narrative means, Stowe speaks to her readers directly in an authoritative/authorial voice, regularly breaking into the fictive stream to assert and document its truth with attested fact. Conrad distances himself from the tale by interposing an internal narrator, Marlow, yarning in retrospect whatever it was that he was able to see, experience, conjecture, or gather from biased informants and hearsay. Additionally, Marlow’s narrative comes to us at a further remove, mediated through the occasionally reactive but mostly neutral voice of one of his shipboard auditors. Out of this difference proceeds a still deeper divide, epistemological and ultimately metaphysical. By so hedging knowledge through his narrative design, Conrad also hedges terminal interpretation. The “meaning” of the tale remains unplumbed, open to endless reflection (some of it Marlow’s), since the hold we are offered is neither definitive nor comprehensive, abysmal rather than exhaustive, always laced with conjecture, never complete. Stowe in contrast is able, if not always willing, to tell all. She withholds, she tells us, some of the worst, hinting only, for example, at the full range of sexual depravity common in the plantation regime, though she leaves no doubt as to its existence. She also bends over backwards to credit the good intentions and humane, civilized character of some of the plantation aristocracy—which the institution of slavery and the system it supports implacably work to defeat and corrupt. In the upshot, her narrative and her judgment leave no room for ambiguity, moral or metaphysical, on the system and those entangled in it. The meaning of any and every event is made clear, the novel is structured (geographically) to drive home a comprehensive meaning, and never, in contrast to Conrad, is the existence of meaningfulness put in doubt.

And yet—setting aside Stowe’s likely indignation and Conrad’s even likelier horror at the suggestion—there are convergences and commonalities. For one thing, both narratives are engaged in a conscious struggle, against the recalcitrance of language and materials and the inertial resistance of audiences, external and (in Heart of Darkness) internal, to satisfy Conrad’s famous formulation of his task: “by the power of the written word, to make you hear, to make you feel—it is, before all, to make you see” (Conrad, preface to The Nigger of Narcissus xiv).[1] More narrowly, there are convergences, contextual, mythopoeic, and epitextual. These include some plausible historical links, personal and political; a narrative progression structured at least in part as a penetration into the heart of darkness; local parallels; and significant echoes in reception history. Indeed, on the level of element and episode, there is a basis for recognizing a substantive intertextuality. All these matters I intend to pursue.

But to what end? I will argue—do here argue—that eliciting these convergences offers more than an insight into the layered workings of Conrad’s imagination. It also furnishes a powerful lens for reading Stowe’s Uncle Tom’s Cabin in the light of its Conradian successor. In the Augustinian tradition of scriptural interpretation, one is enjoined not to read the New Testament in the light of the Old—despite the many places in the gospels where the authority of the prophets and the doings of the patriarchs are used to authenticate the messianic and sacrificial nature of Christ’s ministry. Rather, one is enjoined to read the Old Testament in the light of the New, a practice that flourished into the nineteenth century under the rubric of “typology,” and in a sense that is what I doing here. (For the record, Stowe practices an inverted typology, as in her framing of Tom and his martyrdom as a point-for-point echo of Christ’s ministry.) But it is not that I am just taking the liberty to be unhistorical. History is present but as it were spatialized and in a relation of quantum entanglement. Metacritically, allowing Stowe’s novel and Conrad’s story to be read reciprocally illustrates the convergent nature of two swelling currents of revisionary insight now altering the contours of our critical reading of the past. These address the scale and diffusion of the colonial enterprise and the appetitive inhumanity it let loose, and the tentacular reach of the slave regime in the Atlantic world, phenomena that manifest in the pervasive impact, economic, political, and not least cultural, of their fatally entangled operations.

A third revolutionary current in the last half century of literary studies brings from periphery to core neglected issues of gender. They here come into play in reflecting on the divergent, yet still meaningfully related, histories of reception of the two works, though it is worth remarking that while the capacity of women for heroic action is a salient element in Uncle Tom’s Cabin, it is an altogether rarer phenomenon in Conrad’s writings, Heart of Darkness included. It is with this gender aspect in mind, as it bears on Conrad’s views and practices as a reader, that it is most convenient to start.

I

As far as I know, there is no direct evidence of Conrad’s having read Uncle Tom’s Cabin, or of an interest in any of the writings of Mrs. Stowe, or their immensely popular derivatives in the theater. In fact, almost the only woman novelist Conrad admits to reading (and even relishing) is the widowed, family-connected Marguerite Poradowska, née Gachet, his nurturing partner in an intimate correspondence that bemuses all his biographers.[2] In the aesthetic manifesto that served as the Preface to The Nigger of the Narcissus (1897), besides discounting the appeal of “persuasion” in a novel, he finds occasion for a gratuitous swipe at—among schools—”the unofficial sentimentalism (which like the poor is exceedingly difficult to get rid of)”—the school of fiction, that is, thought to be written by and for women (xv). Such aversions would seem to place him, in his own mind, at the farthest remove from such as Mrs. Stowe. And yet, there are circumstances, public and private, that make an early exposure to Stowe’s novel exceedingly plausible, even probable; an exposure, I wish to argue, carrying sufficient force and staying power, having struck the sensibility of its young reader, to inform the imaginative narrative that we know with certainty emerged from Conrad’s adult experience in King Albert of ![]() Belgium’s Congo fiefdom.

Belgium’s Congo fiefdom.

In his account of becoming a writer in A Personal Record (1912), Conrad observes, “Since the age of five I have been a great reader,” and by the time he was ten (in 1867), “I had read much of Victor Hugo and other romantics. I had read in Polish and French, history, voyages, novels; I knew ‘Gil Blas’ and ‘Don Quixote’ in abridged editions. I had read in early boyhood Polish poets and some French poets.” Knowing no English, he had not yet read Trollope, but “With men of European reputation, with Dickens, and Walter Scott and Thackeray, it was otherwise,” and he marvels at how convincingly Polish he found Mrs. Nickleby and the Crummles and Squeers tribes when speaking the language of his forefathers. He recalls his first taste of English literature in the manuscript of his father’s translation of Two Gentlemen of Verona, remembered as occurring in the sad year following his mother Ewa’s death, when he was seven. Also about then, he had read aloud to paternal satisfaction the proofs of his father’s translation of Hugo’s Toilers of the Sea (70–72).[3] Elsewhere, he credits James Fenimore Cooper, especially the sea tales, and Captain Marryat, as having “through distances of space and time” shaped his very life (“Tales of the Sea” 56). Forced to relocate frequently, and fragile in health, he recalls the grim winter of 1868–69, with his father dying and tended by strangers: “I don’t know what would have become of me if I had not been a reading boy. . . . There were many books about, lying on consoles, on tables, and even on the floor, for we had not had time to settle down. I read! What did I not read!” (“Poland Revisited” 168).

Eighteen sixty-three, the high point of the American Civil War and the year of the Emancipation Proclamation, was also the year of a major insurgency in what had once been the Polish nation. In the period of its clandestine preparation, one of the leading figures of the movement, Apollo Korzeniowski, poet and man of letters, had attracted enough suspicion by 1862 to be sent into exile in northern ![]() Russia with his wife Ewa and their child, Józef Teodor Konrad Korzeniowski, so removing them from the scene of the coming action at a crucial juncture. Health destroyed, and some partial reprieves notwithstanding, first Ewa in 1865, and then Apollo, four years later, would die of tuberculosis, leaving the boy to be marshalled into adulthood chiefly by his uncle, Ewa’s older brother and head of the family estate, Tadeusz Bobrowski.

Russia with his wife Ewa and their child, Józef Teodor Konrad Korzeniowski, so removing them from the scene of the coming action at a crucial juncture. Health destroyed, and some partial reprieves notwithstanding, first Ewa in 1865, and then Apollo, four years later, would die of tuberculosis, leaving the boy to be marshalled into adulthood chiefly by his uncle, Ewa’s older brother and head of the family estate, Tadeusz Bobrowski.

In the buildup to the insurgency, and among all those looking to the restoration of an independent ![]() Poland, a vexed and divisive issue was something labelled, euphemistically, “the peasant question.” Then, as in the earlier November Uprising of 1830, the national feeling found many of its most militant proponents among the hereditary class of land-owning gentry called the szlachta, still politically and culturally privileged but intensely conscious of its former dominance, independence, and ongoing progressive marginalization. Both the Korzeniowskis and the Bobrowskis were of that class, with their Ukrainian estates lying in what once had been greater Poland and now were provinces of mixed population within the Russian Empire. Konrad’s Korzeniowski grandfather, however, had forfeited the family estates by virtue of participation in the events of 1830, so that Apollo (like his dispossessed soldier father) attempted for a while to earn his living by renting and managing the estates of others.

Poland, a vexed and divisive issue was something labelled, euphemistically, “the peasant question.” Then, as in the earlier November Uprising of 1830, the national feeling found many of its most militant proponents among the hereditary class of land-owning gentry called the szlachta, still politically and culturally privileged but intensely conscious of its former dominance, independence, and ongoing progressive marginalization. Both the Korzeniowskis and the Bobrowskis were of that class, with their Ukrainian estates lying in what once had been greater Poland and now were provinces of mixed population within the Russian Empire. Konrad’s Korzeniowski grandfather, however, had forfeited the family estates by virtue of participation in the events of 1830, so that Apollo (like his dispossessed soldier father) attempted for a while to earn his living by renting and managing the estates of others.

The “peasant question” had to do with the status of the peasantry on such landed estates, to which large numbers were bound as serfs, both in Russian-governed “Congress Poland” and the lost Polish territories. Like the land itself, whole villages with their indentured labor force could be rented, bought and sold. Throughout these territories the estate owners were, by and large, Polish (or long-Polonized) gentry, szlachta, educated to roles in the military, the judiciary, and local governance, Polish speaking and Roman Catholic. The enserfed peasantry was typically Ruthenian (Ukrainian), non-Polish speaking, largely illiterate, and Orthodox or Uniat. Culturally, socially, linguistically, religiously, they were other. In the buildup to 1863, an insurgency directed principally against Russia, the Polish nationalist leadership had hopes of enlisting the peasantry in the struggle for independence. Complicating the outlook—apart from the non-Polish peasantry’s loyalties to religion, community, and Tsar—was the argument over emancipation.

Alexander II had opened up the prospect of emancipation throughout the Empire in 1856, whereupon he invited the formation of provincial commissions to study ways toward its realization. His government proclaimed the emancipation of the serfs on Russian private lands in March 1861, hedged about by numerous conditions on timing and subsequent land ownership. In notional Poland, conservative nationalists (“the Whites”), in good part representing the szlachta, countered pressure for emancipation in a liberated Polish nation by projecting the restoration of an imaginary, once prevalent now lost, harmony of peasant and land owner. But some among a more liberal and egalitarian faction (“the Reds”) argued for full and immediate emancipation, along with an entitlement to ownership of allocated farmland. A leading voice within that more radical faction belonged to Apollo Korzeniowski; but even for him the contradiction between szlachta ideals and interests and the revolutionary promise of an emancipated and empowered peasantry was not easily resolved.[4]

In the upshot, the peasantry, especially in the outer reaches of “greater Poland,” proved unresponsive to the emancipatory proclamations of the insurgent leadership, while the Russian authorities countered with generous policies on peasant land ownership and, in March 1864 following the rising, with outright abolition of serfdom in the Polish heartland (not yet fully implemented in Russia), and with other severe and even ruinous penalties aimed specifically at the szlachta. In Conrad’s immediate family, his uncle and future father-surrogate, Tadeusz Bobrowski—who deplored the insurgency and Apollo and Ewa’s part in it as romantic folly—had served on the Tsar’s local and regional commissions on serfdom from 1858 and had advocated a middle course of transitional, qualified emancipation.[5] Closer to Apollo, Ewa and Bobrowski’s younger brother, Stefan—a leader of the insurgency’s Central National Committee—pushed for full and immediate emancipation and an egalitarian state.[6] From this troubled and divided heritage, Conrad, proud as a boy of his szlachta heritage, steeped in the revolutionary patriotism of the great national poets, marked by both the romantic nationalism of his parents and the duty-conscious rationality of his supportive uncle, sought to distance himself, in worlds elsewhere.

By the time the vexed question of “the peasant problem” took on critical importance in Polish revolutionary and land-owning circles, Uncle Tom’s Cabin was well established as an all-time best seller, not only in ![]() America but worldwide, mutating virally into a host of popular forms, especially theatrical. Within a year of publication, an estimated million and a half copies of the novel flooded Great Britain and its colonies. Translations appeared in more than twenty languages, with multiple competing versions in French and German. As to Polish, the

America but worldwide, mutating virally into a host of popular forms, especially theatrical. Within a year of publication, an estimated million and a half copies of the novel flooded Great Britain and its colonies. Translations appeared in more than twenty languages, with multiple competing versions in French and German. As to Polish, the ![]() British Library lists a Chata Wuja Tomasza, Lwów, 1853, with Frantiszek Didacki as probable translator. Another edition appeared in Warsaw in two volumes in 1865 as Chatka Ojca Toma.[7] In France, George Sand roundly declared, in her notable review article on La Case de l’oncle Tom, “It now is no longer permissible for persons who know how to read not to have read it” (319).[8] Her ukase could readily have applied throughout Europe, not least in those parts embroiled in arguments over the continued existence of serfdom.

British Library lists a Chata Wuja Tomasza, Lwów, 1853, with Frantiszek Didacki as probable translator. Another edition appeared in Warsaw in two volumes in 1865 as Chatka Ojca Toma.[7] In France, George Sand roundly declared, in her notable review article on La Case de l’oncle Tom, “It now is no longer permissible for persons who know how to read not to have read it” (319).[8] Her ukase could readily have applied throughout Europe, not least in those parts embroiled in arguments over the continued existence of serfdom.

In Russia, including the ![]() Ukraine, the book was banned until late in 1857—the year following Alexander’s declaration of intent. But French and German and sometimes even English were spoken and read by the educated elite, print was portable, and “many members of Russia‘s literate public of the 1850s read it as an allegorical attack on and description of Russia‘s own serfdom-based society” (MacKay 9). All the more so in the vestigial Polish heartland, where the book was not banned, and where, along with the Polish and other translations, there was also the theater. Stage adaptations were quick to appear in the wake of the novel through much of Europe, including Poland, where, as one scholar notes, “the black tragedian Ira Aldridge’s Polish performances of the 1850s and 1[8]60s [notably Shakespeare] were counterpointed by stage productions of Uncle Tom’s Cabin” with white actors in blackface (Ryan 158).[9] Russians were struck by the similarities between the world of the St. Clares and that of the contemporary Russian estate owner, rendered for us in the writings of Turgenev and Goncharov (Oblomov, 1859). Of St. Clare, one of Herzen’s correspondents exclaims, “Everything about him is Russian,” and then goes on to parallel other Stowe characters with Russian types (MacKay 15).

Ukraine, the book was banned until late in 1857—the year following Alexander’s declaration of intent. But French and German and sometimes even English were spoken and read by the educated elite, print was portable, and “many members of Russia‘s literate public of the 1850s read it as an allegorical attack on and description of Russia‘s own serfdom-based society” (MacKay 9). All the more so in the vestigial Polish heartland, where the book was not banned, and where, along with the Polish and other translations, there was also the theater. Stage adaptations were quick to appear in the wake of the novel through much of Europe, including Poland, where, as one scholar notes, “the black tragedian Ira Aldridge’s Polish performances of the 1850s and 1[8]60s [notably Shakespeare] were counterpointed by stage productions of Uncle Tom’s Cabin” with white actors in blackface (Ryan 158).[9] Russians were struck by the similarities between the world of the St. Clares and that of the contemporary Russian estate owner, rendered for us in the writings of Turgenev and Goncharov (Oblomov, 1859). Of St. Clare, one of Herzen’s correspondents exclaims, “Everything about him is Russian,” and then goes on to parallel other Stowe characters with Russian types (MacKay 15).

During its century of severest repression, literature had come to serve as the chief vehicle of patriotic sentiment and revolutionary fervor in Poland. Apollo’s vocation, as poet, playwright, editor, essayist and translator, and as revolutionary conspirator, was in that heroic tradition. His revolutionary ideals, moreover, kept company with an equally intense religious belief. It would be most surprising if the Christian evangelical and martyrological fervor of Uncle Tom’s Cabin, its domestic values, its rage against institutionalized injustice and individual oppression, its high melodramatic intensity and its pointed rejection of the politics of accommodation, would not have appealed to Apollo (along with its Dickensian tapestry), as directly bearing on his most passionate preoccupations. These were the evils of subjection in all its demeaning and dehumanizing forms, sustained through the oppressive exercise of autocratic power; and the Christ-like, lingering martyrdom of the Polish people. In the years of Conrad’s childhood retreat into omnivorous reading, including Cooper, Frederick Marryat, Hugo, Charles Dickens, and Sir Walter Scott, while his grieving, widowed father was translating Hugo, Dickens, and Shakespeare, planning and contracting with literary journals, and writing for the theater, what are the odds that from the piles of books in his father’s study or from some other friendly source the boy drew out a copy, in French or Polish, of Uncle Tom’s Cabin, so celebrated and available, so attractively exotic, and yet so laden with what was applicable to the life and issues at hand?[10]

1890. En route to the command (as he thought) of a riverboat on the Congo, Conrad embarked on the arduous journey up from the sea, first by boat where the great river was navigable, then on foot and by caravan where it was not, and then again by riverboat. Eventually he would reach ![]() Stanley Falls, more than a thousand miles from the ocean, having steered through much difficult tropical terrain punctuated by disheveled trading stations, bouts of illness, petty company politics and ruinous incompetence, and a voracious extractive trade in ivory. Early in the journey he met and briefly bonded with Roger Casement, who more than a decade later would conduct a crushing investigation into Belgium’s Congo operations, exposing its horrors to the civilized world, which Leopold’s original Societé Anonyme claimed to represent. In his major fictional refashioning of his own Congo experience, Conrad characterizes it as a journey into the heart of darkness.[11]

Stanley Falls, more than a thousand miles from the ocean, having steered through much difficult tropical terrain punctuated by disheveled trading stations, bouts of illness, petty company politics and ruinous incompetence, and a voracious extractive trade in ivory. Early in the journey he met and briefly bonded with Roger Casement, who more than a decade later would conduct a crushing investigation into Belgium’s Congo operations, exposing its horrors to the civilized world, which Leopold’s original Societé Anonyme claimed to represent. In his major fictional refashioning of his own Congo experience, Conrad characterizes it as a journey into the heart of darkness.[11]

Rivers as pathways into the opaque complexities of the land are not uncommon in Conrad’s fiction and would seem to reflect his own maritime and coastal experience. Marlow’s initial ruminations in Heart of Darkness on the ![]() Thames, as once an avenue into Britain’s own heart of darkness, register Conrad’s consciousness of such avenues as having a temporal as well as topographical character, as pathways into the layered past. Their ascent offered both an invitation into the unknown and a ladder of historical regression, reaching as far as “the night of the first ages” (36). “Going up that river,” Marlow says, speaking of the Congo, “was like travelling back to the earliest beginnings of the world, when vegetation rioted on the earth . . . you lost your way on that river as you would in a desert . . . till you thought yourself bewitched and cut off for ever from everything you had known once—somewhere—far away—in another existence perhaps” ( 34). And yet, he adds, there were moments in the journey when one’s past came back, if only “in the shape of an unrestful and noisy dream” (34). So, I would argue, when Conrad returned to his Congo experience as a writer, transforming experience into art, hauntings from “another existence,” somewhere “far away,” emerged and fused with the “overwhelming realities” (34) of the thick, sluggish air and sense of a brooding, implacable force. Among them, evoked in recalling the atmosphere of the journey up the

Thames, as once an avenue into Britain’s own heart of darkness, register Conrad’s consciousness of such avenues as having a temporal as well as topographical character, as pathways into the layered past. Their ascent offered both an invitation into the unknown and a ladder of historical regression, reaching as far as “the night of the first ages” (36). “Going up that river,” Marlow says, speaking of the Congo, “was like travelling back to the earliest beginnings of the world, when vegetation rioted on the earth . . . you lost your way on that river as you would in a desert . . . till you thought yourself bewitched and cut off for ever from everything you had known once—somewhere—far away—in another existence perhaps” ( 34). And yet, he adds, there were moments in the journey when one’s past came back, if only “in the shape of an unrestful and noisy dream” (34). So, I would argue, when Conrad returned to his Congo experience as a writer, transforming experience into art, hauntings from “another existence,” somewhere “far away,” emerged and fused with the “overwhelming realities” (34) of the thick, sluggish air and sense of a brooding, implacable force. Among them, evoked in recalling the atmosphere of the journey up the ![]() Congo with its spectacle of cruelty and systematic exploitation, black misery and white barbarism, coercive violence dressed up as civilizing agency, was another journey up river to a destination whose horrific nightmare character would then also inform Kurtz’s remote and isolated trading station: the journey up the

Congo with its spectacle of cruelty and systematic exploitation, black misery and white barbarism, coercive violence dressed up as civilizing agency, was another journey up river to a destination whose horrific nightmare character would then also inform Kurtz’s remote and isolated trading station: the journey up the ![]() Red River in antebellum

Red River in antebellum ![]() Louisiana to Simon Legree’s isolated plantation in Uncle Tom’s Cabin.

Louisiana to Simon Legree’s isolated plantation in Uncle Tom’s Cabin.

Rivers and river journeys play a large role in Uncle Tom’s Cabin. For the slave populations of the border states, where the novel and then Tom’s martyr’s way begins, there was of course the constant threat of the down-river passage to the slave markets and grinding misery of the cotton kingdom and the rice and cane fields of the deep South. In the chapter called “The Mississippi!”, Stowe hails the scale and scope of the river’s commercial activity, the very embodiment of modern American life. She evokes the moving diorama of its canes and cypresses, the plantation parade of mansions and slave-shack villages as seen from the steamer’s bale-laden decks, as backdrop for that bitter, darker cargo the boat also carries, carries south to market (Ch. XIV).[12] Structurally balancing that down-river movement is the Harris family’s separate and conjoined flight northward, with the ![]() Ohio River in its east-west stretch furnishing the frontier between slave state and free state and the signature scene of Eliza’s perilous crossing on the moving ice. Later,

Ohio River in its east-west stretch furnishing the frontier between slave state and free state and the signature scene of Eliza’s perilous crossing on the moving ice. Later, ![]() Lake Erie serves as the final crossing point to a freedom beyond the reach of the Fugitive Slave Law and the threat of recapture. And throughout the narrative, in hymn and allusion, flickers the promise of the river Jordan.

Lake Erie serves as the final crossing point to a freedom beyond the reach of the Fugitive Slave Law and the threat of recapture. And throughout the narrative, in hymn and allusion, flickers the promise of the river Jordan.

But Tom’s further journey, in chains, from the ![]() New Orleans slave market to Legree’s plantation, takes him up river and into the dark interior, on waters evocative of Acheron and Phlegethon. “The boat moved on,—freighted with its weight of sorrow,—up the red, muddy, turbid current, through the abrupt, tortuous windings of the Red River; and sad eyes gazed wearily on the steep red-clay banks, as they glided by in dreary sameness” (Ch. XXXI, 364).[13] Tellingly, the chapter that reports the journey is entitled “The Middle Passage.” The next, winding through pine barrens, cypress swamps and “slimy, spongy ground,” funereal black moss and rotting stumps, is called “Dark Places” (Ch. XXXII). It carries the epigraph, “The dark places of the earth are full of the habitations of cruelty” (Psalms 74:20).[14]

New Orleans slave market to Legree’s plantation, takes him up river and into the dark interior, on waters evocative of Acheron and Phlegethon. “The boat moved on,—freighted with its weight of sorrow,—up the red, muddy, turbid current, through the abrupt, tortuous windings of the Red River; and sad eyes gazed wearily on the steep red-clay banks, as they glided by in dreary sameness” (Ch. XXXI, 364).[13] Tellingly, the chapter that reports the journey is entitled “The Middle Passage.” The next, winding through pine barrens, cypress swamps and “slimy, spongy ground,” funereal black moss and rotting stumps, is called “Dark Places” (Ch. XXXII). It carries the epigraph, “The dark places of the earth are full of the habitations of cruelty” (Psalms 74:20).[14]

Simon Legree is a brute, coarse and ignorant, and Stowe has him speaking a “low” vernacular; but he is also a man of affairs, “with that air of efficiency that ever characterized him” (Ch. XXXI, 359). The once-handsome house and grounds he inhabits are neglected and dilapidated because Legree runs his plantation “as he did everything else, merely as an implement for money making” (Ch. XXXII, 366). That instrumental approach applies to the working slave population, whose treatment and life expectancy, as against cost of replacement, are simply part of a cost-benefit calculation whose object is optimization.[15] Legree, “like many other planters, had but one form of ambition,—to have in the heaviest crop of the season,” and he has laid bets on it (Ch. XXXVI, 402). His cotton is Kurtz’s ivory. Thanks to the compressions and elisions of the dramatic adaptations of the novel, and the influence of other works (e.g. Boucicault’s The Octoroon, 1859), Legree is often remembered as the brutal Yankee overseer on a more genteelly disposed owner’s plantation.[16] He is indeed a Northern transplant, and he does tell Tom, “I don’t keep none o’ yer cussed overseers; I does my own overseeing” (Ch. XXXI, 361). But it is his plantation, root and branch; and he manages it with a rivalrous pair of toadying black underseers, Sambo and Quimbo. The net result is that he, the only white person in the isolation of the plantation he possesses and rules, is unconstrained in his power over other human beings. He is its absolute tyrant and autocrat. It is Tom’s refusal to act as the instrument of Legree’s unfettered will, to bend to Legree’s unchallengeable authority, that necessitates, in the logic of absolutism, his destruction. Whatever Legree’s natural bent, it is isolation and impunity that empowers him. And it is the dangerous seductions of power, power limited neither by law nor society, that Stowe consistently invokes. “Is man ever a creature to be trusted with wholly irresponsible power?” she asks, in the “Concluding Remarks” appended for the novel’s publication in book form. “And does not the slave system, by denying the slave all legal right of testimony, make every individual owner an irresponsible despot?” (469). As Legree’s quadroon mistress Cassy explains to Tom when she ministers to his grievous wounds, “Here you are, on a lone plantation, ten miles from any other, in the swamps; not a white person here, who could testify if you were burned alive,—if you were scalded, cut into inch-pieces, set up for the dogs to tear, or hung up and whipped to death. There’s no law here, of God or man, that can do you, or any one of us, the least good; and, this man! there’s no earthly thing that he’s too good to do” (Ch. XXXIV, 382-83). The chapter’s epigraph reads, “And behold the tears of such as are oppressed; and on the side of their oppressors there was power. Wherefore I praised the dead that are already dead more than the living that are yet alive” (Ecclesiastes 4:1).

Cassy, driven by despair to the brink of madness and murder, is—by virtue of her banked rage and scorn—the only figure on the scene who can give Legree pause. Stowe describes her as tall, slender, with a face that conveys the idea of a “wild, painful, and romantic history,” once beautiful, now with a “fierce pride and defiance in every line,” and in her eye “a deep, settled night of anguish,—an expression so hopeless and unchanging as to contrast fearfully with the scorn and pride expressed by her whole demeanor” (Ch. XXXIII, 374). Dissuaded from murder (after a brief turn as Lady Macbeth) by Tom’s impassioned Christian piety, she arrives at a plan to exploit Legree’s superstitious propensities, leading—with Tom’s aid and encouragement—to a brilliantly executed escape along with her intended successor and eventually to Legree’s haunted dissolution in drunkenness and death. It is that initial striking presence, however, of regal pride mingled with deepest despair, that would reemerge, “tragic” and “superb” as the helmeted woman among the warriors in the tenebrous heart of Kurtz’s kingdom.

When Legree lies dying, prey to alcoholic delirium with its “lurid shadows” and hallucinations, “None could bear the horrors of that sick room, when he raved and screamed, and spoke of sights which almost stopped the blood of those who heard him” (Ch. XLII, 449). The horrors in Legree’s mind and the horrors of the slave system, converging in the living nightmare of his plantation, push against the limits of what Stowe finds speakable. She regularly reminds us that her rendering of what slavery means for families and individuals can only say the half of it. Cassy tells the newly purchased Emmeline, “You wouldn’t sleep much, if I should tell you things I’ve seen . . . I’ve heard screams here that I haven’t been able to get out of my head for weeks and weeks.” She hints at “a black, blasted tree, and the ground all covered with black ashes” (Ch. XXXVI, 399). Threatening Tom, Legree later amplifies, with a hint of abominable rites and practices: “How would you like to be tied to a tree, and have a slow fire lit up around ye?” (Ch. XXXVI, 404). In her “Concluding Remarks,” Stowe charges her well- disposed Southern readers, in their own secret souls and private conversings, with the knowledge “that there are woes and evils, in this accursed system, far beyond what are here shadowed, or can be shadowed.” And she asks, of the continuing commerce in human property, “And its heart-break and its horrors, can they be told?” She cites mothers who have been driven to save their children by murdering them (Cassy is such a one in the novel, as is Cora Gordon in Stowe’s subsequent novel Dred, and Sethe in Toni Morrison’s gothic Beloved). She sums up: “Nothing of tragedy can be written, can be spoken, can be conceived, that equals the frightful reality of scenes daily and hourly acting on our shores” (Ch. XLIV, 469-70).[17] One senses the frustration, as Stowe speaks of and gestures toward the Unspeakable. It is the very unspeakable that we hear reverberating in Kurtz’s cryptic, haunting, uncharacteristically laconic last words: “The horror! The horror!”

The words “dark” and “darkness” chime obsessively in Marlow’s relation, giving Conrad’s title a resounding iterative resonance. For his early readers, that title would have carried a clichéd familiarity, recalling H. M. Stanley’s best-selling Through the Dark Continent (1878), where Stanley apparently invented the geographic phrase, and In Darkest Africa (1890). The latter title, much echoed and parodied, was immediately appropriated with ironic force in General William Booth’s In Darkest England, and the Way Out (1890), Booth’s Salvationist jeremiad and utopian prescription for his own land, home of the dark Satanic mills.[18] Between Stanley’s two blockbusters, he had become chief agent for development, and ultimately principal mouthpiece, for Leopold’s Congo enterprise. And over the same period, Marlow tells us in the novel, what had been for him a blank space on the map, a “white patch for a boy to dream gloriously over . . . had become a place of darkness” (8).[19]

Placed side by side, Kurtz the fallen idealist and Legree the appetitive brute would seem to have been conceived at the opposite extremes of a spectrum of character. Where the extremes meet is in the suggestion of something missing in each, in effect a blank space in the soul, which—like that on the map—also turns into a place of profoundest darkness. In both instances, that darkness carries a whiff of sulfur, the blasphemous hubristic claim—and, with Kurtz, even the trappings—of appropriated divinity. Stowe writes of Legree, with an eye to the superstitious dread that seizes him in his final disintegration: “to the man who has dethroned God, the spirit-land is, indeed, in the words of the Hebrew poet [Job 10: 21–22], ‘a land of darkness and the shadow of death,’ without any order, where the light is as darkness” (Ch. XXXIX, 425). Kurtz, however, is presented as an exceptional man, originally a talented idealist with high aspirations for doing good in the world, while Legree is presented as a man of coarse appetite and impulse, at the bottom of Stowe’s scale of humanity in moral intelligence. He is her exemplar of what the system allows: that such a man should have unchecked, total power over the lives of others! She puts into the mouth of St. Clare, the most humane of masters, the reflection, first made while travelling through the South, “that every brutal, disgusting, mean, low-lived fellow I met, was allowed by our laws to become absolute despot of as many men, women, and children, as he could cheat, steal, or gamble money enough to buy” (Ch. XIX, 240). And that is Legree. For Conrad, however, it is not Kurtz’s native brutality but his very idealism that is problematic, as tending to screen out reality, to produce high-sounding self-delusion, and to lend itself to corrupt and venal employment. It lives in the hypocritical discourse of the Company’s civilizing mission. The missing something in Kurtz is identified in Marlow’s speculative ruminations, shaped by Marlow’s nautical biases on men and the sea and a pessimism earned through experience. It is some inner check, a fund of simple principle that can survive the paucity of external checks (society and the policeman) and the temptations of unimpeded power. Lacking that inner check, Kurtz the idealist has no scruples as to means in the service of both immediate and remote goals; and so he falls prey to delusional fantasies, primitive appetite, and the freedoms of anomic tyranny.

And yet, even as Kurtz is haunted in his last days—with Marlow as his appalled auditor—by the ghost of his original ideals and aspirations, expressed in his final, terrible cry, so Legree is never entirely bereft of the last vestiges of conscience and moral sensibility, and thus is briefly troubled by Tom’s outrageous claim to personal uprightness, and finally proves vulnerable to retributive fantasies. In his back story, Legree is even offered, with his crude soul in the balance, a moment charged with sufficient grace to redeem him, in line with Stowe’s adamant Christian convictions. But this he rejects and instead claims, in his hellish kingdom, absolute mastery over other souls, where only he determines right and wrong (Ch. XXXIII, 380). And so the “superstitious creeping horror” that seems to fill Legree’s habitation is able to take firm possession of his “dark inner world.” (Ch. XXXIX, 425).

With Legree as the bottom term, Stowe creates a spectrum of exempla, to drive home the pernicious character of “THE SYSTEM”—at its worst in the Cotton Kingdom, but profoundly corrupting wherever it spreads its influence. She systematically demonstrates how it annuls the better inclinations and sympathies of such men as Shelby—a weaker vessel, acting in the end (in his sale of Tom and Eliza’s four-year old, Harry) under the pressure of debt and financial necessity—and St. Clare, a man of high intelligence and fine sensibility reduced to impotence and self-deprecating cynicism, whose insulating attempts at compromise fail and whose resolve to challenge the system comes too late. St. Clare is paired with a twin brother of Roman character, firm, energetic, and efficient, the very platonic form of a successful planter, a pillar of the System, and therewith racist and oligarchic, and prepared to do what is required to sustain it.

Conrad also provides a range, less systematic, embracing “the pilgrims,” European riffraff driven by greed and destructive impulse, like any undisciplined army let loose in an alien setting; and the on-site Director, a self-serving, politicking, bureaucratic mediocrity, whose one great gift is his imperviousness to disease. But Conrad’s most telling portrait (in two flavors) of l’homme moyen sensuel as colonial agent, subject to prolonged isolation like Kurtz, and intolerable boredom, while burdened with power beyond the ability to manage it, comes in his chilling earlier story, “An Outpost of Progress.”[20] There, having been entangled with a band of predatory raiders and slavers in an exchange of men for ivory, Conrad’s protagonists fall out and destroy each other and themselves. No more savagely ironic title can be found in the annals of literature.

The business of slavery, which drives every aspect of Uncle Tom’s Cabin, surfaces sporadically in Heart of Darkness but is also a disturbingly poisonous constant in the background. Conrad’s original ascent of the Congo River to Stanley Falls took him into territory overseen (as arranged by Stanley for the Company) by the notorious Zanzibari raider and slaver, Tippu Tib.[21] Kurtz’s terrorizing, village-destroying ivory raiders follow a program much like that of the Zanzibaris. The system of contracted, indentured, and forced labor that Marlow encounters, prevailing wherever the Company operated, had many of the characteristics of both slavery and serfdom. Marlow’s 200-mile march between navigable sections of the river takes him through country deserted by the population in the wake of the Company’s heavily armed impressment gangs. Before that, on his arrival at ![]() Boma at the end of his sea voyage, one of the first things he sees is “Six black men advanc[ing] in a file, toiling up the path,” under guard and balancing baskets of earth on their heads. “[E]ach had an iron collar on his neck, and all were connected together with a chain whose bights swung between them, rhythmically clinking” (16). Shortly after, Marlow comes upon a grove of the dying, skeletal black contract labor far from home, worn out, discarded, and perishing. The British and specifically English identity that Conrad so avidly courted had staked a claim to exceptional national virtue on its earlier suppression of the slave trade and abrogation of chattel slavery at home and wherever the British flag gave protection and its maritime power extended its reach. And from Conrad’s past—though one cannot argue complete moral equivalence between the lawless and piratical enterprise of black slavery and Eastern European serfdom—there was “the peasant question” that roiled the national politics weighing so fatally on Conrad’s childhood.

Boma at the end of his sea voyage, one of the first things he sees is “Six black men advanc[ing] in a file, toiling up the path,” under guard and balancing baskets of earth on their heads. “[E]ach had an iron collar on his neck, and all were connected together with a chain whose bights swung between them, rhythmically clinking” (16). Shortly after, Marlow comes upon a grove of the dying, skeletal black contract labor far from home, worn out, discarded, and perishing. The British and specifically English identity that Conrad so avidly courted had staked a claim to exceptional national virtue on its earlier suppression of the slave trade and abrogation of chattel slavery at home and wherever the British flag gave protection and its maritime power extended its reach. And from Conrad’s past—though one cannot argue complete moral equivalence between the lawless and piratical enterprise of black slavery and Eastern European serfdom—there was “the peasant question” that roiled the national politics weighing so fatally on Conrad’s childhood.

In a chapter entitled “Liberty”—with an epigraph recalling a speech in the Somerset Case of 1772, where Lord Mansfield’s ruling opened the way to British emancipatory doctrine—Stowe distills the central issues in language that bridge between the history of America and the national aspirations of Conrad’s radical Polish elders.[22] With George and Eliza Harris poised for the last leg of their journey out of bondage, Stowe asks her readers, “What is freedom to a nation, but freedom to the individuals in it? . . . what is freedom to George Harris? To your fathers, freedom was the right of a nation to be a nation. To him, it is the right of a man to be a man . . . ” (Ch. XXXVII, 408). The logic that links nation and individual makes a further brief appearance in the conversation of St. Clare, in the short time left to him after his conversion to activism in the matter of slavery. Looking for positive encouragement in that historic challenge, he turns east: “The Hungarian nobles set free millions of serfs, at an immense pecuniary loss; and perhaps, among us may be found generous spirits, who do not estimate honor and justice by dollars and cents” (Ch. XXVII, 335).[23] Stowe also makes allusion to Poland in its unfree state, in a context that would have spoken particularly to those whose revolutionary agenda targeted autocratic rule. St. Clare is giving an account of his father—”My brother was begotten in his image”—as “a born aristocrat” for whom God was “decidedly the head of the upper classes.” He was also an “inflexible, driving, punctilious businessman,” ruling a large, unruly enterprise by a strict imposition of system, administered and enforced by a brutal overseer, “the absolute despot of the estate.” “The fact is, my father showed the exact sort of talent for a statesman. He could have divided Poland as easily as an orange, or trod on ![]() Ireland as quietly and systematically as any man living” (Ch. XIX. 242–44). Bracketing divided Poland and captive Ireland, two nations deprived of “the right to be a nation,” was not unique to Stowe; and recognizing the continuity between the unfreedom of the nation and the lives of the enslaved/enserfed in society was no great stretch. Tying both deprivations to autocratic despotism follows almost inevitably and points toward what is possibly a clue to explaining a minor puzzle, a seemingly arbitrary touch, in Conrad’s Heart of Darkness.

Ireland as quietly and systematically as any man living” (Ch. XIX. 242–44). Bracketing divided Poland and captive Ireland, two nations deprived of “the right to be a nation,” was not unique to Stowe; and recognizing the continuity between the unfreedom of the nation and the lives of the enslaved/enserfed in society was no great stretch. Tying both deprivations to autocratic despotism follows almost inevitably and points toward what is possibly a clue to explaining a minor puzzle, a seemingly arbitrary touch, in Conrad’s Heart of Darkness.

Conrad needs an informant to help us and Marlow form an adequate picture of Kurtz’s regime and influence. Such an informant needn’t be fully aware of all that he is telling us or share in the view he helps create. And in fact Conrad makes him something of a holy innocent, dressed in Harlequin rags and patches and apparently enjoying the charmed life attributed to fools, drunks, and madmen. He is also, to Marlow, an embodiment of the pure, youthful, unselfish spirit of adventure. But why does Conrad make him a Russian?[24]

Marlow’s first contact with the Russian is in clues: a stack of firewood for the hungry stern-wheeler; a note of warning to approach Kurtz’s station cautiously; and a well-thumbed book on seamanship, British in origin, and with penciled notes in a seeming cipher—which turns out to be Cyrillic. When finally encountered at Kurtz’s station, their author presents “a boyish, beardless face, very fair,” and Marlow gathers “he had run away from school, had gone to sea in a Russian ship; ran away again; served some time in English ships; was now reconciled with the arch-priest,” his father ( 53–54). In his personal history then, he is mutatis mutandis the young Conrad; in his compulsive need to speak, to unburden himself to an auditor, he is the mature Marlow. But why Russian?

One glaring contrast that follows from the antithesis of Stowe’s venal brute and Conrad’s deformed idealist is in the responses of those they rule. Legree, who rules by terror, division, and the whip is heartily hated and feared. Kurtz, having come down on the interior lake villages with thunder and lightning—”He could be very terrible” (57)—is worshipped, having turned the villagers into his raiders and followers, whose dread of losing him provokes, first their violence, and then “such a tremulous and prolonged wail of mournful fear and utter despair as may be imagined to follow the flight of the last hope from the earth” (47). Their god—whom the corruptions of power remote from countervailing checks had led to preside at “unspeakable rites” offered up to him ( 51), and to post the shrunken heads of “rebels” who resist his will — was abandoning them.

The mature Conrad’s intense repugnance toward the contemporary epitome of the autocratic state with its presiding “Emperor and Autocrat of All the Russias” appears at its bluntest in a substantial essay published in the Fortnightly Review in the wake of Russia‘s ignominious defeat by an ascendant Japan. That was in 1905, six years after the writing of Heart of Darkness. Titled “Autocracy and War,” it is a strange essay, ruminative, associative, part retrospective fulmination, part cold-eyed prophesy. It includes a ferocious diatribe against autocratic Russia as, in effect, Kurtz’s Congo station writ large. Conrad sees Russian autocracy as a thing apart, rootless and inexplicable. “What strikes one with a sort of awe is just this something inhuman in its character. It is like a visitation, like a curse from Heaven falling in the darkness of ages upon the immense plains of forest and steppe lying dumbly on the confines of two continents: a true desert harbouring no Spirit either of the East or of the West.”

The curse had entered her very soul; autocracy, and nothing else in the world, has moulded her institutions, and with the poison of slavery drugged the national temperament into the apathy of a hopeless fatalism. It seems to have gone into the blood, tainting every mental activity in its source by a half-mystical, insensate, fascinating assertion of purity and holiness. The Government of Holy Russia, arrogating to itself the supreme power to torment and slaughter the bodies of its subjects like a God-sent scourge, has been most cruel to those whom it allowed to live under the shadow of its dispensations. (Conrad, Notes on Life and Letters 98)[25]

In Heart of Darkness, the Russian is to Kurtz as a worshipful acolyte. He believes in Kurtz as transcending mere mortality, despite all that is erratic and arbitrary in his actions, including seizing the Russian’s own small cache of ivory because Kurtz “had a fancy for it, and there was nothing on earth to prevent him killing whom he jolly well pleased” (57). But Kurtz “can’t be judged as you would an ordinary man,” says the Russian. And his devotion, fed by Kurtz’s gift for grandiose eloquence, was not reasoned Marlow says, or in any way meditated. It was religious. “It came to him, and he accepted it with a kind of eager fatalism” (56)—the fatalistic, unquestioning devotion, in short, of a believing Russian (and even Ruthenian) peasant for his Tsar.

Marlow tells us a short third of the way into his narration that the thing he hates, detests, can’t bear above everything is a lie (27). It is then a most mordant irony that, moved in spite of himself by Kurtz’s Intended’s desperate need for “something—something—to—to live with,” Marlow produces his reluctant lie: that the last word Kurtz pronounced was—not “The horror!”—but “your name” (79). He so leaves intact, at least for the Intended, “that great and saving illusion” of a noble Kurtz and a noble unsullied love, in place of the monstrous truth, the unspeakable reality (77). And yet, before coming to this pass, Marlow has talked himself into the convoluted insight that somehow, through his unsparing self-surrender in his solitary venture into the heart of darkness, Kurtz had attained a kind of martyred greatness, requiring a kind of loyalty. That his cry, “The horror!” was in fact an “affirmation, a moral victory paid for by innumerable defeats, by abominable terrors, by abominable satisfactions. But it was a victory!” (72). Kurtz had at the last faced, with the courage of his extremity and despair, unbearable personal and metaphysical truths. Such paradoxical figuration of a via negativa marked by extremism, by a heroic rejection of lukewarm virtue and the safety of moderation, has considerable redemptive efficacy in Christian thought. It challenges a more conventional, straightforward view of martyrdom as a deposit in the bank of salvation. In pushing Marlow to the brink of these speculative quicksands, Conrad is putting a twist on a martyrology that is salient in the national mythography of the Poland he left behind and also in the narrative typology of Uncle Tom’s Cabin, where it may be presumed that its deployment found responsive resonances among early Polish readers. The entanglement of the two martyrdoms—Poland‘s and diaspora Africa’s—is not so easily discerned in Conrad’s thought and feeling, but the prevalence and power of the trope of Poland as the crucified Christ in the world of Conrad’s youth—and its congruence with Stowe’s parable—cannot be gainsaid.

When Conrad tells us that in his early boyhood he had read the Polish poets, these included the greatest of Poland‘s Romantic national poets, his father’s model and hero, Adam Mickiewicz. Mickiewicz had given the trope of Poland, crucified by the Nations and yet their potential Savior, some of its strongest expression, above all in his multi-part verse drama, Forefathers’ Eve (Dziady, the name of a traditional Slavic Feast of the Dead). Mickiewicz dedicates its climactic Third Part (1832) “To the Holy Memory” of his martyred fellow students, themselves inspired by the suffering and endurance—unparalleled, he suggests, since the time of the early Christians—of the Polish people. In the initial scenes, set in a prisoners’ cell, the blood of the students, who are being hauled off to exile, is compared to the blood of Christ, sacrificed for Man’s salvation. It is there that the poet-protagonist sheds his former romantic libertinism and re-baptizes himself as the poet-patriot Konrad (after the hero of Mickiewicz’s earlier Konrad Wallenrod).

In the third scene, Konrad goes through his own despairing Promethean/ Luciferian moment, a dark night of the soul from which he is rescued by Father Piotr, who drives out that devil, interrogating and then banishing it. Later, in his monk’s cell, Father Piotr is the vehicle of an apocalyptic vision of a martyred and redeemed Poland wherein first “A tyrant has arisen, Herod! Lord, the youth of Poland/ Is all delivered into Herod’s hands.” Here it is the white roads running north, “as rivers flow,” that constitute the road to Calvary, carrying their burden of captive humanity into penal exile and oblivion. Poland is then crucified on a cross with arms that shadow all of Europe, a cross “Made of three withered peoples, like dead trees.” Given vinegar and bile to drink, pierced and bleeding, forsaken and despairing, the nation expires while “Mother Freedom stands below and weeps.” But the nation overcomes its bloody martyrdom, despair, and death; ascends in Messianic triumph; and while its earthly agent is set above all kings and peoples (“Upon three crowns he stands, himself uncrowned”), it wraps in its redemptive, spreading garment “all the world” (Mickiewicz 124–127).[26]

The crucial scene in Poland’s historical martyrdom was a sparagmos, the progressive three-way partition by its neighbors, Russia, Prussia, and ![]() Austria, that ended its unity and autonomy and opened an unending cycle of oppression, displacement, reckless revolt, and savage repression. Apollo Korzeniowski’s 1857 poem on his son Konrad’s christening, “Born in the 85th year of the Muscovite Oppression,” catches the dark mood:

Austria, that ended its unity and autonomy and opened an unending cycle of oppression, displacement, reckless revolt, and savage repression. Apollo Korzeniowski’s 1857 poem on his son Konrad’s christening, “Born in the 85th year of the Muscovite Oppression,” catches the dark mood:

Baby son, tell yourself

You are without land, without love,

Without country, without people,

While Poland—your Mother is entombed. (Najder, Joseph Conrad, 13)

Two years earlier, Korzeniowski deploys the imagery of Calvary to characterize a peasant agitation (also invoked in his treatise, Poland and Muscovy) where the insurgents (Ukrainian), unsupported by the szlachta, were brutally cut down:

Serfs back to work, back to factory!

Peasant rising: noble and clean,

Crucified by lords infamous and mean,

The Tsar laughs like a demon . . . (Najder, Joseph Conrad, 10)[27]

In the ambient gloom, the scourge (knout), the bloody crown of thorns, the crushing weight of the Cross, massacres of the Innocents, Calvary itself, and the torment and mutilation of the saints, so vivid in Catholic and Orthodox imagery, all found ready application in the drama of the people’s and the divided nation’s suffering.

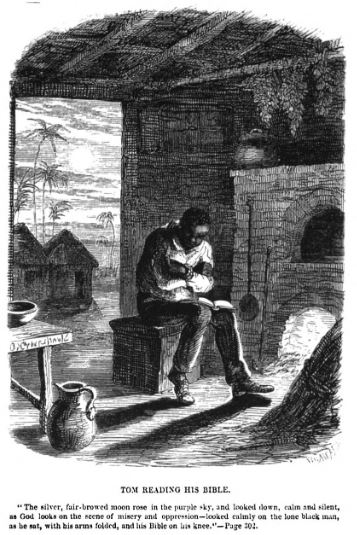

Figure 3. Illustration by George Cruikshank for Uncle Tom’s Cabin entitled “Tom Reading His Bible.” Printed in the 1852 Cassell edition.

Stowe’s figuration of Christian martyrdom and of Christ crucified compasses, not only Tom, the individual, but also the whole of the nation’s slave community and the African continent itself. It is elaborated in Tom’s story almost from the beginning, where, despite his pass for travel, he declines the opportunity to run away from his impending sale and declares, “If I must be sold, or all the people on the place, and everything go to rack, why, let me be sold” (Ch. V, 46). He then carries through his sacrificial ministry at waystations signposted by a temptation in the wilderness, a Gethsemane moment of “soul crisis,” a brutal flagellation, and ultimate martyrdom in a Place of Skulls. When God is silent and Tom falls prey to “tossings of soul and despondent darkness,” so that even his Bible offers no comfort, Legree comes out of the night: “You see the Lord an’t going to help you: if He had been, he wouldn’t have let me get you! . . . Ye’d better hold to me; I’m somebody, and can do something!” Though rejecting this tempter’s injunction to “heave that ar old pack of trash in the fire, and join my church!”, Tom is left at a spiritual nadir, until he is afforded a vision of Christ, buffeted and bleeding, crowned with thorns which mutate into rays of light, and is enjoined to overcome “even as I also overcame” (Ch. XXVIII, 413–15).[28]

Stowe opens the chapter (XL, “The Martyr”) that represents Tom’s Calvary with a recapitulation of his long walk through “the valley of slavery” and into that dark night of the soul. His final martyrdom follows upon his heroic refusal to betray the escapees, and Stowe again finds herself speaking of the unspeakable. “What man has nerve to do, man has not nerve to hear. What brother-man and brother-Christian must suffer, cannot be told us, even in our secret chamber, it so harrows up the soul! And yet, oh my country! these things are done under the shadow of thy laws! Oh Christ! Thy church sees them, almost in silence!” (Ch. XL, 438). From Nation and Church, Stowe returns to Tom and hammers home the message of Christ re-crucified. We hear that standing beside him in the torture was “ONE,—seen by him alone,” while also beside him stood Legree, “[t]he tempter . . . blinded by furious, despotic will.” Before losing consciousness, Tom forgives Legree “with all my soul!”; and when his executioners, Sambo and Quimbo, “took him down, and, in their ignorance, sought to call him back to life,” he forgives them too, and in a last effort of the spirit brings them the gospel message, winning, we are told, both their souls, and so—between two thieves—scoring one better than Jesus (438–40).

Earlier, when urging the gospel of Love upon a bitter, vengeful Cassy (Cassy: “Love! . . . love such enemies. It isn’t in flesh and blood”), Tom explains that being able to love and pray over all and through all, “that’s the victory.” Stowe then enlarges the view to embrace both race and continent: “And this, oh, Africa! latest called of nations,—called to the crown of thorns, the scourge, the bloody sweat, the cross of agony,—this is to be thy victory . . . ” (Ch. XXXVIII, 421). But Africa’s Christ-like redemptive agency in the world as Tom’s creator imagined it, like Poland’s imagined messianic liberation of the nations of despot-ridden Europe, was not soon in arriving. On the brink of a feverish new era of exploitative occupation, partition, and suffering when Stowe wrote, Africa as Conrad found it, like the Poland he had left, had plenty of the scourge, the sweat, and the cross in its nostrils, but—for at least three more generations and two world wars—not much of a scent of victory.

II

Nothing in the early reception of Heart of Darkness resembles the domestic impact of Uncle Tom’s Cabin or its phenomenal eruption into global ubiquity and acclaim. Both writings began in the modest circumstances of serial publication to limited attention, but then their courses diverged, with Uncle Tom’s Cabin achieving swift celebrity and Heart of Darkness ascending only gradually into literary canonicity as a powerful critique of the colonial and imperial enterprise and a modernist narrative masterpiece in the form of a voyage of existential discovery.[29] But in the post-World War II era of civil rights struggle and colonial emancipation, their critical fortunes took a similar turn. After stretches wherein the moral and political bearings of the two works were reductively conventionalized in the case of Stowe, and conscientiously subordinated to, first formal, and then psycho-symbolic readings in the case of Conrad, both came under attack on literary and political grounds. In each case the challenge produced controversy, defensive argument, and, happily, fresh currents of interpretive understanding.

Stowe’s early reception in America was by no means universally welcoming. In the slave-holding South and in the party-press, anti-abolitionist sectors of the North, her novel evoked many abusive critiques, especially of its claims to a truthful representation of slavery as an institution, with its unconscionable legal scaffolding, deleterious domestic norms, and abusive, often horrific plantation discipline. In response, Stowe compiled Uncle Tom’s Cabin (1854), her weighty “illustration” and defense of the novel’s factual grounding.[30] In subsequent years, though never out of print, the novel was effectively displaced in popular consciousness by dramatic versions and the long-lasting “Tom shows,” where Topsy’s hijinks, Eva’s angelic pathos, Liza’s sensational perils, and Tom’s submissive devotion, choked out the thematic centrality of institutional depravity, racial injustice, and the eponymous protagonist’s moral heroism. Uncle Tom declined, post Reconstruction, from a figure of exemplary strength and integrity to a byword for sycophantic accommodation.

Though Heart of Darkness, as it ascended into academic canonicity, found recognition as a seminal work—as the seminal work—of literary anti-colonialism, other critical perspectives tended to dominate the conversation before Conrad’s tale encountered the deconstructive challenges to liberal assumptions in the climate of disintegrating colonial empires, indigenous liberation movements, Black Power, Civil Rights, post-colonial theory, and Viet Nam. Conrad’s own perspectives on the heterogeneous imperial enterprise, and the justice of his representations of race, gender, and politics, came under fresh scrutiny, inviting conceptual reframing and extensive critical argument.

It is certainly worth noting that the two most arresting challenges to the settled pieties on Uncle Tom’s Cabin and Heart of Darkness in the post-war era came, not from literary scholars, but from novelists, also men of letters, who were or would soon prove to be of the first rank. Early in his writing career, in an essay called “Everybody’s Protest Novel,” James Baldwin challenged any claim to literary value for Stowe’s century-old work. First published in the socially engaged organ of “the New York Intellectuals,” The Partisan Review (1949), Baldwin’s was an all-out attack on the Novel with a Purpose, as inherently hobbled and confined, its advocacy entailing categorization and generalization, precluding any deeper engagement with the unclassifiable and the particular in the living human being.[31] Baldwin’s standard is an art that never compromises the irreducible individuality of the person or the relationship, whether by race or status or (presumably) gender, or by any other scheme of social categorization—the many hierarchies of otherness. In the novel’s attempt to link truth to a cause, the human being is made less human. “In overlooking, denying, evading, his complexity,—which is nothing more than the disquieting complexity of ourselves—we are diminished and we perish . . . ” (580). In the instance of his prime example, Stowe, he writes, “was not so much a novelist as an impassioned pamphleteer” (579). Moreover, “Uncle Tom’s Cabin is a very bad novel, having, in its self-righteous, virtuous sentimentality, much in common with Little Women” (578–79).

Baldwin goes on to spell out what he means by “sentimentality,” and it is in that, rather than in the association with Louisa May Alcott, that he is at odds with later readers like Jane P. Tompkins, who outed a male establishment bias behind such disdainful fastidiousness and recovered the contemporary contexts, generic, discursive, and affective, that underpinned Stowe’s impact and achievement.[32] To Baldwin, writing in the shadow of the literary stoicism common to the era, “Sentimentality, the ostentatious parading of excessive and spurious emotion, is the mark of dishonesty, the inability to feel . . . [and thus] the signal of secret and violent inhumanity, the mask of cruelty” (579). Baldwin illustrates the dishonesty masked by the spurious emotion in observing that, apart from a set of “stock” figures, Stowe “has only three other Negroes in the book . . . and two of them [Eliza and George] may be dismissed immediately, since we have only the author’s word that they are Negro and they are, in all other respects, as white as she can make them” (580). In her “virtuous rage” and moral panic over blackness, he writes, “She must cover their intimidating nakedness, robe them in white, the garments of salvation.” Consequently, Tom, “her only black man, has been robbed of his humanity and divested of his sex. It is the price for that darkness with which he has been branded” (581). The humanity of her black characters is thus wholly reduced or evaded, as Baldwin sees it, with a cast that is, variously, mere mechanical automata, bleached practically white, or metaphysically sterilized.[33] Baldwin strays into Achebe territory in anticipation, when he likens the good intentions of the protest novel—as exemplified in Uncle Tom’s Cabin—to “something very closely resembling the zeal of those alabaster missionaries to Africa to cover the nakedness of the natives, to hurry them into the pallid arms of Jesus and thence into slavery” (583). Achebe’s charge against Conrad is on the face of it quite opposite—that he takes part in parading the supposed nakedness of the savages, their primitive, sub-human nature. In both cases, however, the charge is against an authorial effacement of the full humanity of the abused race.

Chinua Achebe delivered his indictment of Heart of Darkness in a Chancellor’s Lecture at the University of Massachusetts, Amherst, a quarter century later.[34] To bring home his challenge to the bona fides of this sacred, “anti-colonial” text, Achebe calls attention to Conrad’s almost complete withholding of speech from his Black Africans, endowing them instead with a cacophony of uncouth grunts and cries, and so annulling individuality and inwardness in a display of primitive animality. He fixes on Heart of Darkness as exemplary of Western failures to engage the reality of Africa, provoked not just by the novel’s canonical ubiquity in educational curricula but also because, “better than any other work that I know,” it displays “the need—in Western psychology to set Africa up as a foil to Europe, as a place of negations at once remote and vaguely familiar . . . ” (3). As for Marlow’s brooding implication of a kinship between the Congo and the Thames as he winds into his tale, Achebe argues the story itself makes of the Congo “the very antithesis of the Thames” and Marlow’s reminder of the Thames’s history as “one of the dark places of the earth” is meant as a warning. Having conquered its primitive darkness, the Thames would do well to keep its distance and avoid the risk of “an avenging recrudescence” through exposure to its still primordial relative (4). He sees in Marlow/Conrad’s appalled reportage, as at the scene of the dying, abandoned workers, “bleeding-heart sentiments,” the kind of liberalism that sidesteps ultimate questions of equality. He urges that what cannot be got round in Conrad’s text is “the dehumanization of Africa and Africans,” and he memorably concludes (after anticipating and demolishing the defense that Conrad, or Marlow, merely spoke the language of their time), “that Joseph Conrad was a thoroughgoing racist” (10-12).[35] Nevertheless, Achebe argues that it is a communal need that this “offensive and deplorable book” (14) serves. He finds a brilliant literary analogy for how that works: “Africa is to Europe as the picture is to Dorian Gray—a carrier on to whom the master unloads his physical and moral deformities so that he may go forward, erect and immaculate” (17).

Achebe was not the first to aim a deflationary barb at Heart of Darkness. He cites F. R. Leavis’s irritation with the verbal mystifications in Conrad’s reiterated appeals to the inexpressible, the inconceivable, the inchoate, serving merely to pump up “a ‘significance'” (218–221). Irving Howe amplified, asking whether, in its “straining for some unavailable significance,” the novel wasn’t “a kind of parable about Conrad the writer, a marvellously colored and dramatized quest for something ‘unspeakable,’ which proves to be merely unspecified?” (82). Ironically, it was that charged intimation of unspeakable depths, most notably in the readings of Albert J. Guerard, that set the default interpretive approach in the midcentury academy.[36] Nevertheless, a number of influential critics on the left in the post war, cold war period identified Conrad’s abiding stature with his political penetration and notably with his anatomy of imperialism and colonialism.[37] On that plane, Marlow’s derisive reduction in Heart of Darkness of the civilizing and heroic-progressive rationales for Western ground-level imperialism is not easily bettered. Stripped of those furbelows, “It was just robbery with violence, aggravated murder on a great scale . . . The conquest of the earth, which mostly means the taking it away from those who have a different complexion or slightly flatter noses than ourselves, is not a pretty thing when you look into it too much” (7). Achebe’s essentially humanist argument did not in itself void these anti-imperial credentials—though Conrad’s evasion of any general challenge to British imperialism did not escape notice. Achebe’s driving idea—remarkably like Baldwin’s—is as stated in a later essay: “Africans . . . ask for one thing alone—to be seen for what they are: human beings” (“Africa’s Tarnished Name” 89). And yet, Achebe’s exposure of a latent racism rooted in a psycho-social compulsion, manifest even in so canonical an example of anti-imperial revulsion as Heart of Darkness, laid down a marker for the momentous revolution in literary studies that brought forward suppressed voices and alternative histories, unspoken assumptions and covert agendas, issues of race and gender, and the fundamental role of colonialism, imperialism, and the transatlantic slave trade in the shaping of the West. Against that background, Conrad’s admirers—among them, Patrick Brantlinger, Fredric Jameson, Maya Jasanoff, Edward Said, Ian Watt, an equivocal V. S. Naipaul, an unflappable W. G. Sebald—managed to develop a more nuanced view of his complex entanglements with all these issues, not least in Marlow’s retelling of his Congo River journey into the heart of its darkness.[38]

Among the revisionist views given impetus by the new amplitude of subject and inquiry were those concerning Conrad and gender. Conrad’s entrenched profile had long been that of a writer of stories in a distinctly masculine vein, with masculine subject matter and masculine appeal for a male audience (like that of Marlow’s shipboard listeners in Heart of Darkness). The early preponderance in his fiction of shipboard communities and loner’s intrusions in exotic places; the association with narratives of adventure and exploration and with Marryat and Cooper’s nautical romances; and the paucity of women, or their peripheral and subordinate presence, earned such gendering characterization an easy acceptance. Certainly nothing in Heart of Darkness called it into question, neither the magnificent and enigmatic spectacle of Kurtz’s grieving black mistress nor the pale apparition of the Intended, Kurtz’s votary, whom Marlow protects from knowledge of the monstrous truth. In a challenging essay from 1987, “The Exclusion of the Intended from Secret Sharing in Conrad’s Heart of Darkness,” Nina Pelikan Straus takes up these very elements—and drives home the masculinist characterization. She anatomizes the dynamics whereby the chivalrous “protective” exclusion of the Intended, given such heavy emphasis, signposts the exclusion of the woman reader in so far as she is unwilling to unsex herself and abandon that aspect of who she is. A counter argument of comparable force had to wait for Ruth Nadelhaft’s Joseph Conrad, where—disentangling Conrad from his narrators—she gives granular attention to the far from negligible body of Conrad’s women characters and their situations; and for Susan Jones’s Conrad and Women, where the author makes her case, not so much by disputing Straus on Heart of Darkness but by invoking such tangible influences as Conrad’s intimate correspondent Marguerite Poradowska and bringing into focus vivid and complex female figures in Conrad’s other fiction. These include the Haldin women and Sophia Antonovna in Under Western Eyes (1911), Winnie Verloc in The Secret Agent (1907), and others; but Jones’s principal study is of Flora de Barral in Chance (1913), whose story is the spine of the novel (Conrad’s first popular and lucrative success). In Flora de Barral, Conrad offers an acute portrait of a psychologically battered young woman who cannot trust being loved, as conveyed and partly construed by Marlow. But in Jones’s cogent discussion, it goes oddly unremarked that Flora, like the Intended, is in the end forever shielded from the truth, in Flora’s case about her poisonous, parasitic father, a would-be murderer and a suicide.

Though Conrad, as I have noted, was chary of even acknowledging familiarity with fiction in the popular vein favored and often written by women, that didn’t prevent its giving shape and character to aspects of his writing. Such appropriation, or at least engagement, is most keenly pursued by Jones in Conrad and Women. Jones writes:

Critics of Conrad have supplied us with an extensive record of his literary sources, showing us the traditions, both philosophical and narratological, that sustained his fiction. We have learned that he drew on sources ranging from Schopenhauer, Darwin, Pater, French realism, impressionism, Dickens, Henry James, the male adventure tradition, and the detective novel. What has gone unnoticed, however, is Conrad’s intriguing engagement with women’s writing. (192)