Abstract

This contribution to BRANCH documents the historical and biographical conditions surrounding the publication of John Pentland Mahaffy’s controversial volume The Decay of Modern Preaching (1882). Although often deemed to be a secular or even heretical thinker, Mahaffy emerges here as a thoughtful scholar of religion standing at the crossroads of faith and reason. In the years preceding the publication of The Decay of Modern Preaching, Mahaffy witnessed a number of changes at Trinity College Dublin that threatened the principles he deemed essential both to good preaching and to intellectual culture more broadly. Mahaffy’s views on intellectual work and religion were mutually sustaining, a fact that helps to enrich our understanding of this important text, its troubled reception in the nineteenth century, and the evolving narrative of nineteenth-century faith.

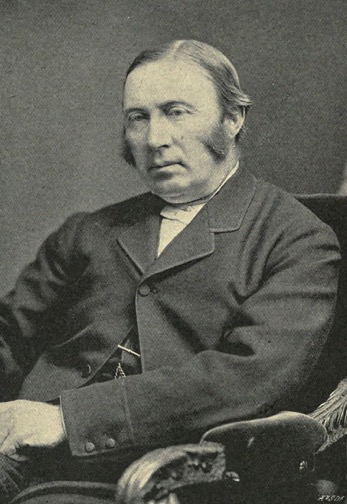

John Pentland Mahaffy (1839-1919) died on 30 April 1919. At the time of his passing, he was extolled as the “most learned Irishman of our day,” and for good reason (“John Pentland Mahaffy,” Methodist Review 507). Mahaffy was elected a Fellow of ![]() Trinity College Dublin in 1864, assumed a Chair in Ancient History in 1871, and served as Provost from 1911 until 1914. Four years later, he was made a Knight of the Great Cross of the British Empire. Mahaffy was a prolific scholar, publishing in a range of genres: monographs, translations, editions, book reviews, travelogues, and critical introductions. His subject matter ranged from the classical literature that was his life’s passion to rhetoric, European philosophy, institutional history, and educational policy. This is to say nothing of his abundant contributions to the major periodicals of the day on everything from Greek drama to Irish politics. [1] In the words of American clergyman Henry Clay Trumbull (1830-1903), he was known as “an authority in the field of Greek antiquities, as well as a scholar of wide learning in various other fields,” and as a “painstaking and systematic worker,” as another commentator observed, who brought the past to life before the reader’s very eyes (Trumbull 314; “Euripedes” 121-22).

Trinity College Dublin in 1864, assumed a Chair in Ancient History in 1871, and served as Provost from 1911 until 1914. Four years later, he was made a Knight of the Great Cross of the British Empire. Mahaffy was a prolific scholar, publishing in a range of genres: monographs, translations, editions, book reviews, travelogues, and critical introductions. His subject matter ranged from the classical literature that was his life’s passion to rhetoric, European philosophy, institutional history, and educational policy. This is to say nothing of his abundant contributions to the major periodicals of the day on everything from Greek drama to Irish politics. [1] In the words of American clergyman Henry Clay Trumbull (1830-1903), he was known as “an authority in the field of Greek antiquities, as well as a scholar of wide learning in various other fields,” and as a “painstaking and systematic worker,” as another commentator observed, who brought the past to life before the reader’s very eyes (Trumbull 314; “Euripedes” 121-22).

Yet in 1881—at the very height of his professional success—Mahaffy was charged with heresy. He makes an obscure allusion to this affair in a letter to George Macmillan (1855-1936), dated 19 November 1881:

I sent up a reply which made them hop, and I have not heard one more word about it. I have asked to have the correspondence printed but they wouldn’t have it at all. So my lovely correspondence is merely filed on their minutes and will no more be seen. (qtd. in Stanford and McDowell 131)

True to this account, the details of the heresy charges remain lost to history, though William Stanford and Robert MacDowell hypothesize that it may well have originated in a sermon delivered in the College Chapel, in which Mahaffy drew historical comparisons between St. Paul and the Greek Stoics, hence boldly conflating Christian and pagan traditions (131). According to Lord Alfred Douglas (1870-1945), it was the only time Mahaffy was ever to deliver a sermon at that venue.[2] Mahaffy’s passion for classical scholarship repeatedly chafed against his identity as an avowed Christian and Protestant cleric, and it is certainly plausible that his penchant for juxtaposing Hellenic and Scriptural source material might have been taken as irreverent. Without concrete documentation, however, the reason for the College’s allegations must remain shrouded in mystery.

What we do know is that less than a year later, Mahaffy published a rigorous reappraisal of the Anglican clergy: a book-length theological treatise called The Decay of Modern Preaching (1882). If the circumstances surrounding the charges of heresy remain inscrutable, it is clear that Mahaffy’s conflict with the Anglican Church was not merely incidental—it was a conflict in which he was invested and which, to some extent, he openly invited. The Decay of Modern Preaching was to become one of the most controversial and, in later years, most overlooked of Mahaffy’s works. The fullest discussion of the book appears in Stanford and McDowell’s biography, Mahaffy: A Biography of an Anglo-Irishman (1971), which treats it as “an apologia as well as a critique […] partly a justification of his own inability to preach an effective sermon, partly an attack on hypocrisy, partly a defence of art against naïve naturalism, and partly a criticism of narrow doctrinalism” (132-34). Their account, which spans a scant five pages, presents Mahaffy as an “unclerical cleric,” whose faith was perhaps more cultural than theological in orientation (127).

Figure 1: Portrait of John Pentland Mahaffy, Cassell’s Universal Portrait Gallery (London: Cassell, 1895), p. 400.

This article charts the religious history of J.P. Mahaffy leading up to the publication of The Decay of Modern Preaching. Rather than treating Mahaffy as a skeptic or casual observer of Anglican practice, I present him as a historian of the ancient past who insisted that faith and reason were compatible and even mutually sustaining. Indeed, it was in part Mahaffy’s efforts to deploy historical narrative in the service of faith that inspired wariness and even hostility among contemporary reviewers. To some extent, Mahaffy’s historical treatment of religious institutions sets him in league with German higher critics like David Strauss (1808-1874), whose 1835 Das Leben Jesu—translated into English by George Eliot as The Life of Jesus (1846)—differentiated between the mythic status that Christian tradition conferred upon Jesus and the historical reality of his life. Unlike Strauss, Ludwig Feuerbach (1804-1872), or Ernest Renan (1823-1892) however, Mahaffy was less interested in advocating for Christ as a historical figure than he was in tracking the history of Christian institutions—institutions that in the nineteenth century, he maintained, tended to emphasize religious feeling at the expense of intellectual training.[3] In the eyes of his critics, Mahaffy treated preaching as a secular vocation, despite his insistence that The Decay of Modern Preaching constitutes a “heart-searching” endeavor to query and thereby reaffirm the value of faith (Decay 7). Emerging from the institutional context of Trinity College Dublin, where religious and intellectual culture maintained a close but at times troubled relationship, The Decay of Modern Preaching illuminates how even those thinkers who identified with evangelical culture struggled to navigate the complex intersections of faith and secular thought at the end of the nineteenth century.

The Legacy of J.P. Mahaffy

Mahaffy has often been treated as a secular or even pagan thinker. To some extent, this is owing to his relationship with Oscar Wilde (1854-1900), who would come to represent for many late Victorians a rejection of conventional moral codes.[4] Wilde matriculated at Trinity College Dublin in 1871 and found in Mahaffy a devoted tutor and mentor, famously noting that he was his “first and best teacher” (Complete Letters 562). Scholars have frequently claimed that Mahaffy was the first to introduce Wilde to the study of Hellenism and, by association, to its culture of hedonistic excess.[5] Without question, Mahaffy was wary of Wilde’s relationship with David Hunter-Blair (1853-1939), who had converted to Catholicism in 1875 and reportedly provided his friend with sixty pounds to defray the expenses of his travels to ![]() Rome just two years later.[6] Mahaffy successfully diverted Wilde from Rome to show him the wonders of

Rome just two years later.[6] Mahaffy successfully diverted Wilde from Rome to show him the wonders of ![]() Greece. In a letter to his wife, he reported that the young Wilde had “come round under the influence of the moment from Popery to Paganism, but what his Jesuit friends will say, who supplied the money to land him in Rome, it is not hard to guess. I think it is a fair case of cheating the devil” (qtd. in Stanford and McDowell 41). For his own part, Hunter-Blair insisted that Wilde returned from his travels “Hellenized […] perhaps somewhat Paganized” by his time with Mahaffy (Hunter-Blair 136). From this point on, scholars have often treated Mahaffy as a thoroughly secular voice. In the words of Boris Brasol, “the extravagances of his atheistic catechism used to shock even his agnostic co-religionists” (23).

Greece. In a letter to his wife, he reported that the young Wilde had “come round under the influence of the moment from Popery to Paganism, but what his Jesuit friends will say, who supplied the money to land him in Rome, it is not hard to guess. I think it is a fair case of cheating the devil” (qtd. in Stanford and McDowell 41). For his own part, Hunter-Blair insisted that Wilde returned from his travels “Hellenized […] perhaps somewhat Paganized” by his time with Mahaffy (Hunter-Blair 136). From this point on, scholars have often treated Mahaffy as a thoroughly secular voice. In the words of Boris Brasol, “the extravagances of his atheistic catechism used to shock even his agnostic co-religionists” (23).

Yet Wilde did not altogether abandon his interest in Catholicism after his trip to Greece; as Iain Ross points out, Wilde continued to draw comparisons between Hellenic and Catholic traditions throughout his life (29-10). By the same token, even if Mahaffy attempted to illuminate for Wilde the “worst faults of Popery,” it hardly seems accurate to suggest that his interest in Hellenic culture amounted to the adoption of a pagan or profane worldview (Complete Letters 44). Mahaffy took great care to establish that the Greeks were neither licentious nor irreligious, observing that there was “much sound moral feeling in Greece” (158). He refused to “assert the hard contrast between Greek and modern piety,” proposing instead a controversial parity between the two (Social Life 348). The writings of the Greeks, he observes,

are the writings of men of like culture with ourselves, who argue with the same logic, who reflect with kindred feelings. They have worked out social and moral problems like ourselves, they have expressed them in such language as we should desire to use. In a word, they are thoroughly modern, more modern even than the epochs quite proximate to our own. (1)

Although Mahaffy may have inspired in Wilde a passion for the Greeks, it is hardly likely that his teachings celebrated the hedonistic excesses of the ancient world. If anything, Mahaffy took pains to establish that the Hellenic model of moral perfection bore a striking resemblance to the evangelical spirit of the nineteenth century. While it is always difficult to establish the religious views of historical figures with certainty—faith is, after all, a complicated and deeply personal matter—Mahaffy’s legacy as a pagan or atheistic thinker seems, at the very least, worth reexamining.

There were, to be sure, other reasons his contemporaries might have deemed Mahaffy unconventional in his religious views. Mahaffy treated Christianity as a historical development that bore the traces of former periods rather than as a spontaneous revelation of divinity. He claimed, for instance, that Christianity had absorbed certain principles of Greek philosophy, noting in particular that Stoicism had influenced St. Paul and thus laid the groundwork for the historical rise of Christian thought (343). In Social Life in Greece (1874), he went so far as to set the religion of ancient Greece alongside Christianity and admitted that the latter did not fare well by the comparison:

But I confess that when I compare the religion of Christ with that of Zeus, and Apollo, and Aphrodite, and consider the enormous, the unspeakable contrasts, I wonder not at the greatness, but at the smallness of the advance in public morality which has been attained. It is accordingly here where the difference ought to be greatest, that we are led to wonder most at the superiority of Greek genius which, in spite of an immoral and worthless theology, worked out in its higher manifestations, a morality equal to the best type of modern Christianity. Socrates and Plato are far superior to the Jewish moralist [St. Paul], they are far superior to the average Christian morality; it is only in the matchless teaching of Christ himself that we find them surpassed. (8)

Although Mahaffy insists that Christ is the supreme exemplar of culture and virtue, his attempt to compare Christ and the Greek philosophers would have been controversial at this time. In effect, Mahaffy’s account implied that Christian thought did not constitute an unmitigated victory over the alleged excesses of the pagan world so much as an extension of its underlying spirit. Christianity was itself, by this account, a historical phenomenon—not a final truth so much as an institutional practice subject to change or even amendment over time.

To profess a belief in divinity while also treating religion as a secular institution was admittedly a delicate balancing act, as would be pointed out by Joseph McCabe (1867-1955), a former Roman Catholic priest who became a leading figure in the Rationalist movement at the turn of the twentieth century. In The Story of Religious Controversy (1929), McCabe invoked Mahaffy’s scholarship to justify his claims that paganism was no more synonymous with immorality than Christianity was with virtue. He notes that as a “Protestant clergyman” and the nineteenth century’s foremost authority on Greek literature, Mahaffy constitutes an especially reliable authority on the matter, but adds somewhat wryly: “Professor Mahaffy is bound to hold that Christianity is superior to paganism; but he is singularly unfortunate in vindicating his belief” (176). McCabe goes on to observe that at certain moments in The Social Life of Greece (including the passage cited above), Mahaffy “betrays the embarrassment which his professional, and no doubt personal, zeal for his religion causes” (176). McCabe was eager to leverage Mahaffy’s remarks in the service of an explicitly Rationalist agenda, yet there is also some truth to his claim that Mahaffy’s defense of Christianity is somewhat strained. As we shall see, however, the uneasy tenor of Mahaffy’s remarks were less a consequence of declining faith than they were the expression of a rhetorical predicament. The product of an education that prized exegesis, Mahaffy believed in the close alliance of religious and intellectual study; nevertheless, it was precisely this focus on textual and historical scrutiny that led him to be regarded by many as an irreligious and even secular thinker.

The Real History

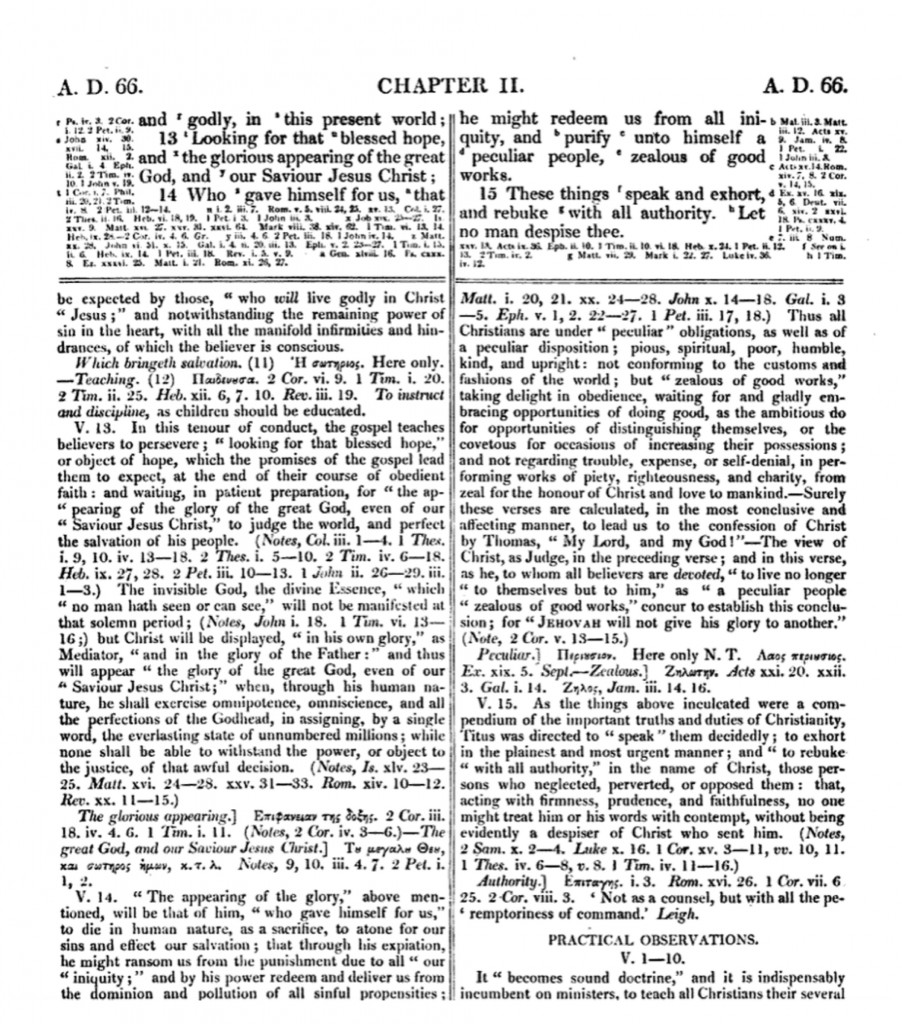

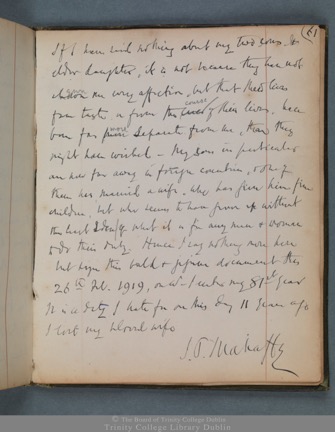

Mahaffy was deeply invested in the evangelical culture of the ![]() Dublin society in which he was raised, as he recounts in his unpublished autobiography, A Brief Summary of the Principal Stages of My Life (1919), currently housed at Trinity College Dublin (see figure 3). Mahaffy was the son of clergyman Nathaniel Mahaffy (1798-1897) and Elizabeth Pentland (1789-1894), who guided her children through the Scripture, as Mahaffy himself puts it, with the aid of “Mr. Scott’s very practical Evangelical commentary” (Brief Summary 5). The reference is to Thomas Scott’s (1747-1821) A Commentary on the Whole Bible (1788-1792), an immense work of Biblical exegesis featuring the Old and New Testament and accompanied by extensive cross-references and textual analysis. As Figure 2 illustrates, Scott’s marginalia often occupied more space than the original text and, by offering explanatory notes occasionally accompanied by diagrams and extensive documentation, it afforded the reader a comparative, transhistorical, and analytical approach to theology. By his own account, Mahaffy had undertaken this course of Biblical study at least six times by the age of fourteen.

Dublin society in which he was raised, as he recounts in his unpublished autobiography, A Brief Summary of the Principal Stages of My Life (1919), currently housed at Trinity College Dublin (see figure 3). Mahaffy was the son of clergyman Nathaniel Mahaffy (1798-1897) and Elizabeth Pentland (1789-1894), who guided her children through the Scripture, as Mahaffy himself puts it, with the aid of “Mr. Scott’s very practical Evangelical commentary” (Brief Summary 5). The reference is to Thomas Scott’s (1747-1821) A Commentary on the Whole Bible (1788-1792), an immense work of Biblical exegesis featuring the Old and New Testament and accompanied by extensive cross-references and textual analysis. As Figure 2 illustrates, Scott’s marginalia often occupied more space than the original text and, by offering explanatory notes occasionally accompanied by diagrams and extensive documentation, it afforded the reader a comparative, transhistorical, and analytical approach to theology. By his own account, Mahaffy had undertaken this course of Biblical study at least six times by the age of fourteen.

His religious education, however, was not confined to textual study. “All the society that I knew or saw,” Mahaffy recalls of his youth, “were observant of religion. Such a thing as going out for a Sunday’s excursion without going to Church was thought scandalous” (Brief Summary 35). He routinely visited the cottages on his mother’s estate in ![]() County Monaghan where, as he notes, “most of her tenants were R.C. [Roman Catholic] but the richest of them Protestants, who were also the most respectable and the least agreeable. We were always most welcome in the homes and cabins of the poor, always asked to make a ‘cayley’ [party]” (55). Mahaffy describes these tenants as “delightful, sympathetic Roman Catholic peasants (as yet undefiled by politics)” (56), which suggests that he was perhaps not vehemently anti-Catholic, as some scholars have suggested. Assuredly, Catholic support for a free and independent

County Monaghan where, as he notes, “most of her tenants were R.C. [Roman Catholic] but the richest of them Protestants, who were also the most respectable and the least agreeable. We were always most welcome in the homes and cabins of the poor, always asked to make a ‘cayley’ [party]” (55). Mahaffy describes these tenants as “delightful, sympathetic Roman Catholic peasants (as yet undefiled by politics)” (56), which suggests that he was perhaps not vehemently anti-Catholic, as some scholars have suggested. Assuredly, Catholic support for a free and independent ![]() Ireland would prove a decisive point of contention for Mahaffy, a staunch Unionist, in later years.[7]

Ireland would prove a decisive point of contention for Mahaffy, a staunch Unionist, in later years.[7]

Figure 2: Excerpt from The Holy Bible, Containing the Old and New Testaments,

with Original Notes, Practical Observations, and Copious Marginal References

[1788-1792], ed. Thomas Scott (Boston: S.T. Armstrong, 1822).

Mahaffy was proud that his mother introduced him to theological perspectives that were not, strictly speaking, her own. Still, his exposure to these celebrated Catholic preachers clearly did not win him over to their cause. Years later, addressing the Royal Commission on University Education in Ireland, Mahaffy would write of Newman: “We delighted to hear him preach, and preach Catholic doctrine, and we were not the least bit afraid that he would convert us, because we had been taught our own creed properly” (Great Britain 215). In keeping with tradition, Mahaffy was ordained in the Church of Ireland when he became a fellow of Trinity College Dublin in 1864.

Although ordination was customary, in this case it also forecasted how intertwined religion and institutional culture would become for Mahaffy in the coming decades. Mahaffy maintained a strongly Protestant-Unionist identity, and in later years he inveighed against the intrusion of Catholicism into Irish politics in pieces like “The Romanisation of Ireland” (1901). It is largely on these grounds that Mahaffy has been understood as anti-Catholic. Although it is difficult to determine how deeply his theological opposition to Catholicism may have been, it is worth noting that even Mahaffy’s most outspoken remarks on the Catholic question tend to focus on political and institutional matters. In “The Romanisation of Ireland,” for instance, he opens by distancing himself from either doctrinal or party politics: “The problem is one which cannot but occupy the politician and the theologian; but both of them may condescend to listen to what the historian has to say” (32). From this point forward, Mahaffy tracks how the redistribution of power among the gentry, and the democratization of Ireland, led more Catholics to assume positions of public influence. “No just man can say they are to blame,” he observes, “except in mistaking the interests of Rome for the interests of Ireland” (37). Mahaffy’s chief objection, here and elsewhere, is less to the Roman Catholic faith than to the increased role of Catholicism in Irish governance, the spread of Irish nationalism, and educational policy. Although Mahaffy’s political and religious affiliations are unmistakable, by assuming the role of historian he attempts to separate matters of moral and cultural value from what he regards as the more practical matters of institutional governance. In short, he seeks to elude theological controversy by occupying a footing that is, at least on the surface, neither theological nor political.

Figure 3: Manuscript page from John Pentland Mahaffy, A Brief Summary of the Principal Stages of My Life, p. 133. Used with permission, courtesy of the Board of Trinity College Dublin.

Mahaffy’s relationship to religious practice and to Catholicism in particular was not simply a matter of doctrinal fidelity or even of his avowed Unionism. Without question, he was wary of the Roman Catholic presence in Ireland, though he was not without sympathy for either their social condition or worship practices. Recalling how he had been warned from boyhood “not to trust the ‘false papists’” (Social Life 100), Mahaffy recognized that a strictly anti-Catholic worldview occluded important cultural and historical contexts: “the long oppression of the Roman Catholics, and their enforced separation from Protestant society, has created a clan feeling, which, in times of great bitterness and bloodshed, has been known to outweigh even the closest ties of friendship toward the enemies of the clan. In this way, what one side translates as faith towards country and religion, the other call traitorous betrayal of friends and relations” (100). To this extent, Mahaffy saw himself as operating within a very precarious political atmosphere in which religion had come to be uncomfortably aligned with institutional and intellectual priorities. While Mahaffy appreciated the spirit and even certain elements of Roman Catholic practice—he favored, for instance, the “Roman Catholic law of celibacy”—he was deeply concerned about the integration of religious and political institutions (Decay 127). Hence, one of the great flaws of “those theological colleges in favour with the Roman Church and the extremest Protestants alike” was, in Mahaffy’s view, a tendency to bring faith to bear on a world that did not abide strictly by spiritual laws—to present all lessons “with a bias and flavour of theology” (139). Unaccustomed to seeing the world through a layperson’s eyes, he argues, the student who attends such an institution might well struggle to apply the lessons of their faith to the world at large.

The implication, of course, is that a Protestant education did not entail such risks, and this was a presumption that was widely shared at Trinity College Dublin at the time. Earlier in the century, reformers had attempted to abolish denomination tests, which determined eligibility for university scholarships. In 1868, the Board of Trinity College Dublin had resisted these efforts, proclaiming that the “Protestant character of Trinity College should be preserved” (qtd. in Webb 106). The disestablishment of the Church of Ireland in 1871 revoked from Trinity College Dublin the right of nomination to select parishes in ![]() Ulster, but it was not until the passing of the University of Dublin Tests Act, also known as Fawcett’s Act, in 1873 that the institution’s religious character began to change in visible ways.[9] Although the passing of Fawcett’s Act was delayed, in part owing to William Gladstone’s (1809-1898) unsuccessful efforts to establish a federalized university system in Ireland, it resulted in the removal of all religious tests at Trinity College Dublin (except for those in the Divinity School), stipulated that Fellows must no longer take orders, and excused non-Anglicans from attending chapel. While continuing to assert a Protestant identity, the institution was gradually relenting on religious requirements as a prerequisite for university study. As Daniel Webb puts it, the “atmosphere of the College was religious but not clerical, tolerant but not indifferent, undenominational but not formally secular” (107).

Ulster, but it was not until the passing of the University of Dublin Tests Act, also known as Fawcett’s Act, in 1873 that the institution’s religious character began to change in visible ways.[9] Although the passing of Fawcett’s Act was delayed, in part owing to William Gladstone’s (1809-1898) unsuccessful efforts to establish a federalized university system in Ireland, it resulted in the removal of all religious tests at Trinity College Dublin (except for those in the Divinity School), stipulated that Fellows must no longer take orders, and excused non-Anglicans from attending chapel. While continuing to assert a Protestant identity, the institution was gradually relenting on religious requirements as a prerequisite for university study. As Daniel Webb puts it, the “atmosphere of the College was religious but not clerical, tolerant but not indifferent, undenominational but not formally secular” (107).

Competition with the Catholic University over resources and students—as well as concerns about how it might transform the intellectual culture of Dublin—caused Mahaffy no small degree of worry. In 1880, just two years before he began to write The Decay of Modern Preaching, a charter founding the Royal University of Ireland allowed the Catholic University to reconstitute itself as University College Dublin. The change was significant. Since Newman’s departure in 1858, the Catholic University had suffered from diminishing enrollments and resources.[10] When students were permitted to take examinations and thus acquire degrees through the Royal University, the institution gained students and cultural legitimacy. In Mahaffy’s view, Trinity College Dublin had failed to effectively maintain its intellectual clout in light of these developments. To him, the mediocre quality of teaching practiced by Fellows of Trinity College Dublin warranted reevaluating the training of the Protestant clergy, especially as the institution encountered growing opposition from “competitions, from party politics, from disappearance of our clientele, the Protestants of Ireland,” many of whom still elected to complete their educations at ![]() Oxford and

Oxford and ![]() Cambridge. He continues: “RC [Roman Catholic] students will not be allowed to come here truly, and hence in great numbers, until the RC [Roman Catholic] clergy control our education” (Brief Summary 50-51).

Cambridge. He continues: “RC [Roman Catholic] students will not be allowed to come here truly, and hence in great numbers, until the RC [Roman Catholic] clergy control our education” (Brief Summary 50-51).

If Trinity College Dublin was “undenominational but not formally secular” (Webb 107), then, the same might well be said of Mahaffy. Protestantism had come to represent for him not merely the faith of his boyhood but a particular approach to culture and society. To be sure, he observed in Catholicism two salient comparisons to Greek religion: the alliance of art and divinity, and “the embracing of all the pleasures of human nature within the services performed in honour of the gods” (Social Life 379). Nevertheless, he insisted that these were merely comparisons of “outward form.” The “whole temper and spirit” of Catholicism, he maintained, is “thoroughly anti-Greek” in its preference for religious doctrine over spiritual inquiry (378). In Mahaffy’s view, the intellectual spirit of Protestantism coincided with his own religious education. With the aid of Scott’s Commentary, Mahaffy had become adept in the practice of biblical criticism, which sought to elude religious dogma by reading Scripture through a lens of historical and rhetorical speculation. If some regarded such methods as antithetical to faith, Mahaffy insists that even the most rational, analytical works are evocations of a spirit that is essentially Protestant. In his 1880 volume Descartes, for instance, he remarks that although the philosopher “might be a Catholic, a Conservative in faith, a pet pupil of the Jesuits; he was nevertheless in temper a Protestant, a sceptic [sic], the spiritual father of Spinoza” (148). Here, Mahaffy suggests that the very spirit of Protestantism is embodied in the rational philosophy of René Descartes (1596-1650) and in Baruch Spinoza’s (1632-1677) Tractatus Theologico-Politicus (1677), which has argued that organized religions represent different interpretations of Scripture, rather than embodying spiritual truth itself. The Protestant spirit was, in many ways, inseparable from a system of modern inquiry that was historical, comparative, and rationalist. For Mahaffy, this method was not only the foundation of his religious identity; it directly informed the method of intellectual scrutiny he would apply to all of his future work as a scholar.

The Decay of Modern Preaching

Based upon two lectures Mahaffy gave at the ![]() Midland Institute of Birmingham on 17 and 24 March 1882, The Decay of Modern Preaching takes as its premise the claim that nineteenth-century preaching was less inspiring and less effective than it had once been. The truth of this claim is difficult to assess.[11] As William Gibson notes, the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries “saw preaching reach its highest point in terms of popularity and influence; it also saw sermons diversify and specialize” (4). Yet it is precisely owing to the diversification of the sermon—in both form and content—that the scope of its influence is so hard to appraise. Adding to this difficulty is the fact that nineteenth-century assessments frequently blur the distinction between the act of preaching and the text of the sermon. Accordingly, the response of a parishioner listening to a preacher’s words might differ significantly from the response of a reader examining the text from the comfort of home. Even as sermons continued to be popular reading for Victorian audiences, the private experience of a sermon seemed to set the value of independent judgment over the authority of the preacher as a divine oracle.

Midland Institute of Birmingham on 17 and 24 March 1882, The Decay of Modern Preaching takes as its premise the claim that nineteenth-century preaching was less inspiring and less effective than it had once been. The truth of this claim is difficult to assess.[11] As William Gibson notes, the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries “saw preaching reach its highest point in terms of popularity and influence; it also saw sermons diversify and specialize” (4). Yet it is precisely owing to the diversification of the sermon—in both form and content—that the scope of its influence is so hard to appraise. Adding to this difficulty is the fact that nineteenth-century assessments frequently blur the distinction between the act of preaching and the text of the sermon. Accordingly, the response of a parishioner listening to a preacher’s words might differ significantly from the response of a reader examining the text from the comfort of home. Even as sermons continued to be popular reading for Victorian audiences, the private experience of a sermon seemed to set the value of independent judgment over the authority of the preacher as a divine oracle.

In 1877, J. Baldwin Brown (1820-1884) observed that the “power of the pulpit is manifestly on the wane” (Brown 107). In Brown’s view, the reason was transparent: a “flood of cheap and, on the whole, valuable literature has overspread the country, and has entered homes hitherto most jealously guarded from intellectual raids” (Brown 107). Although the influence might be regarded as salutary, he explains, the result is that preaching as a practice has become comparatively less vital to religious life in the second half of the century. Indeed, when Victorian preaching was taken to task it was often on the grounds of failing to adapt to expanding literacy rates, which had cultivated a keener awareness of Scriptural debates among the general public. As Hughes Oliphant Old puts it, the “Victorian pulpit remained by and large ‘precritical’,” failing to respond directly to the challenges of nineteenth-century biblical criticism (350). Although the claim may not account for all preachers, some of whom were very much engaged with the challenges of the higher criticism, it is a charge that Mahaffy would echo in The Decay of Modern Preaching.

The religious fervor of the early nineteenth century, Mahaffy avers, was due almost entirely to the efforts of great preachers, who “manifested their eloquence in their evangelical theology” (Brief Summary 36). This combination of religious knowledge and rhetoric, he suggests, had become less common by the 1880s, in part because preachers had failed to adapt to the rapidly evolving cultural landscape of the nineteenth century. At the beginning of The Decay of Modern Preaching, Mahaffy laments that Christian forms of worship have remained largely unaltered since its inception, dependent upon the stability and infallibility of the cultural rituals attached to it. “Nothing is more marked in most Christian preachers,” he writes,

than the firmness with which they hold and declare that their form of faith was established once for all by its Founder, and that no change or modification whatever is to be tolerated by the orthodox. This rigid adherence to the doctrines of Christianity is extended even to the very formin which it is preached, and nothing is thought better or more profitable than to repeat the old watchwords of those who once stirred the world to its depths. (Decay 13-14)

Figure 4: Title Page for John Pentland Mahaffy,The Decay of Modern Preaching (New York: Macmillan and Co., 1882).

The preachers of early Christianity, Mahaffy claims, were cultural revolutionaries. Advocating for a single theology in a pantheistic world, these innovators were driven to argue passionately for their ideas: “They were to hate father and mother and brethren for His sake; they were to quarrel with the whole civilised world, and set themselves apart as a peculiar society” (15). If Mahaffy’s prose reflects an admiration for the religious tolerance of the pagan world, it also conveys an appreciation for the earliest Christian preachers, whom he presents as provocative and daring.

The problem, then, was not actually doctrinal in nature. On the contrary, even the well-meaning preacher found himself faced with “a society which cares not to be disturbed, which hates to be alarmed, and which desires little more from the pulpit than a confirmation of its prejudices” (33). By the 1880s, Mahaffy contends, the preacher’s office was merely to reinforce the incontrovertible truth of Christian dogma through the repetition and reiteration of old ideas. His own view of the preacher’s calling was quite different. Because theology is by its very nature “a science full of mystery,” the man of the deepest faith and greatest capacity for guiding others must eschew simple answers and, on occasion, invite challenges to tradition (88). “No man will be great as a teacher,” he observes, “who is felt to be avoiding the burning topics of the day” (47). One of the chief obstacles to addressing such topics in the form of a sermon was, Mahaffy maintains, the preacher’s misguided assumption that intellect is antithetical to faith. Nineteenth-century parishioners were, among the middle and upper classes, more highly educated than they used to be. “They no longer want instruction from the pulpit,” he writes, “when they can find it in thousands of books; nor will they be led by the opinions of men who are not superior to themselves in intellect and culture, often not even in training” (155). With the rise of literacy came an inevitable shift in the role of the preacher, who could no longer be looked upon as the bearer of specialized knowledge.[12] Mahaffy’s view of preaching, then, was that it must advance original thought, inspiring in listeners a new relationship to old ideas.

It was a popular and by no means original argument. John Henry Newman had made a similar claim in a sermon preached on 1 May 1856 at the ![]() University Church in Dublin—suggestively, around the time Mahaffy reports attending Catholic sermons across the city.[13] His remarks indicate that intellect and piety, while distinct, are also mutually sustaining, especially in the context of religious education and the training of the clergy. The “great misfortune, and our trial,” Newman avers, is that “the two are separated, and independent of each other; that, where power of intellect is, there need not be virtue; and that where right, and goodness, and moral greatness are, there need not be talent” (5). Mahaffy’s view bears a striking resemblance to that of Newman whom, though by this time Catholic, Mahaffy had long admired for his intellectual acumen. Similar arguments surfaced in the years just preceding the publication of Mahaffy’s The Decay of Modern Preachingin Robert William Dale’s (1829-1895) Nine Lectures on Preaching (1878), Thomas Armitage’s (1819-1896) Preaching: Its Ideal and Inner Life (1880), Austin Phelps’s (1820-1890) Preaching: What to Preach and How to Preach (1882), and John W. Etter’s (1846-1895) The Preacher and his Sermon: A Treatise on Homiletics (1882), to name only a few. All of these writers highlight the need for a fresh approach to preaching and a few, like Dale, propose bringing the calling more in line with the modern audiences it seeks to reach. For Dale, too many preachers prioritize knowledge of Scripture over rhetoric, forgetting that reason alone cannot arouse spiritual awakening:

University Church in Dublin—suggestively, around the time Mahaffy reports attending Catholic sermons across the city.[13] His remarks indicate that intellect and piety, while distinct, are also mutually sustaining, especially in the context of religious education and the training of the clergy. The “great misfortune, and our trial,” Newman avers, is that “the two are separated, and independent of each other; that, where power of intellect is, there need not be virtue; and that where right, and goodness, and moral greatness are, there need not be talent” (5). Mahaffy’s view bears a striking resemblance to that of Newman whom, though by this time Catholic, Mahaffy had long admired for his intellectual acumen. Similar arguments surfaced in the years just preceding the publication of Mahaffy’s The Decay of Modern Preachingin Robert William Dale’s (1829-1895) Nine Lectures on Preaching (1878), Thomas Armitage’s (1819-1896) Preaching: Its Ideal and Inner Life (1880), Austin Phelps’s (1820-1890) Preaching: What to Preach and How to Preach (1882), and John W. Etter’s (1846-1895) The Preacher and his Sermon: A Treatise on Homiletics (1882), to name only a few. All of these writers highlight the need for a fresh approach to preaching and a few, like Dale, propose bringing the calling more in line with the modern audiences it seeks to reach. For Dale, too many preachers prioritize knowledge of Scripture over rhetoric, forgetting that reason alone cannot arouse spiritual awakening:

because the thought is there and not the fire, these preachers suppose that they are more‘thoughtful’ than their brethren. It would be just as reasonable to suppose that a skeleton in a surgeon’s cupboard has more bones than a living man. The living man has quite as many bones as the skeleton; and besides the bones he has flesh and muscle; an eye that may be filled with sunshine or with tears; a voice than can command, or entreat, or comfort; a hand that can help or strike. (30)

Dale shared Mahaffy’s desire for a reappraisal of the preacher’s practical training and a recognition that the preacher’s office depended as much on reason and rhetoric as it did on passion and piety. “Since we have to preach,” Dale remarks, “we ought to learn how to preach well” (93).

The difference was perhaps in Mahaffy’s characteristically provoking manner of presenting his claims. Whereas Dale had suggested simply that one must strike a balance between intellectual and emotional energy—and where Newman maintained that sanctity was the more enduring value—Mahaffy claimed that piety was not a sufficient or even a necessary attribute in a preacher. On the one hand, Mahaffy noted that some exceptionally gifted men might be discouraged from pursuing the curacy for fear that they lack the purity of character required of such a post: “He stands at the threshold of his ministry with the jar of this discord within him” (Decay 62). On the other hand, the man who comes to the ministry with some experience of the world and its iniquities might well prove to be the better curate. Mahaffy writes:

He who has lived, in many sense of the term, intensely, even passionately, is often a more interesting man from many aspects than he who has merely kept clear of dangers. He is interesting because he possesses a stronger, bolder nature, which is guided, sometimes, at least, by great and noble impulses; he is interesting because he knows what suffering is as well as joy; in fact, he may be forgiven much, because he has loved much. In any case he knows the great interests and great temptations of the world really, and not by hearsay, and can estimate the amount of good and evil in human nature which the theoretical observer only guesses from the outside. (132)

Mahaffy seems to suggest here that the best preacher—the one most capable of communicating with his parishioners—is one who has known the world and its sins. As a practical suggestion it would seem to have some value, as might his suggestion that all preachers should study rhetoric.[14] Yet his vision of the preacher as a man of the world—flawed, rational, and carefully translating divine revelations into modern parlance—was, for some readers, all too secular.

Mahaffy’s most controversial claim of all was that religion was itself a product of human endeavors in this world and thus subject to historical change. Here, once again, his assumption of the role of historian proves problematic. He writes:

And yet there have been great reforms in religion; even since the revelation of the Gospel, there have been great changes in faith. But they were all justified as returns to the original purity of the Bible, which had been corrupted by men. In no case have reformers ventured to preach their gospel as new; they have always insisted upon its being a return to the old and therefore to the pure. (98)

On the face of it, Mahaffy proclaims that it was precisely the novelty and flexibility of Christianity that helped to secure its influence. Yet his historical sensibility also leads him to question the nineteenth-century impulse to preserve earlier forms of worship. Not only does such an effort contravene the spirit of Christianity, Mahaffy observes, it is also grounded in historical inaccuracies:

It is not necessary to inquire here how far this claim of all religious reformers to have merely returned to the primitive faith of their ancestors in its original purity can be historically maintained. It is likely enough that if a modern Protestant and a Christian of the second century met in the flesh, they would be astonished at the mutual divergence in their spiritual views, still more in their religious forms. It may, indeed, be fairly argued that an absolutely unmodified return to what existed centuries ago is perfectly impossible, and that any restoration must contain much that is new, infused into it by the spirit of the age. (99-100)

In the end, then, the cultural attachment to outdated subjects, rhetorical forms, and faith practices was not merely impractical: being “anachronistic, out of time and place, and preached to congregations who are estranged from that particular dogma in their Christianity,” they bore little relationship to the reality of Christian practice (104).

Mahaffy’s religious education had taught him that faith could assume many different forms and was expressed—even within the same Christian denomination—in many different ways. What is more, he would have learned from his close study of Thomas Scott’s exegetical writings that the languages, rituals, and popular reception of Scripture evolved over time, and this historical sensibility was at the root of his desire to reform the modern practice of preaching. As an illustration of this point, he turns to the intersection of religious and political languages, noting that the God of the Old Testament approximates our modern conception of a despot: “Our highest conception is that of a constitutional king, who establishes wise and beneficent laws, and binds himself to act in conformity with them, even though he have the power to reverse or violate them” (110). Hence, while God’s omnipotence may “afford the Absolutist in theology a strong ground for denying the analogy between modern kings and the great King of kings,” Mahaffy observes that the layperson may struggle to reconcile his own political principles with the ideas being preached from the pulpit: “this logical side of the matter will not outweigh the feeling in the minds of modern congregations, that despotism is not the highest form of government, and therefore the modern preacher will do well to study with care that constitutional side of God’s government which corresponds to the temper of our society” (112).

When The Decay of Modern Preaching was published in 1882, Mahaffy occupied a position of intellectual and cultural authority. But contemporary reviews of the book, while often invoking Mahaffy’s intellectual prowess, largely expressed disappointment and perplexity at his central claims. Nearly all reviewers proclaim, as does a notice in The New Englander, that Mahaffy “assumes the decay of modern preaching to be a fact,” noting that the book is “grossly incorrect” if taken as an appraisal of American preaching; the “defects of the book,” the reviewer concludes, “are fundamental” (“Notices” 710). Another reviewer remarks that Mahaffy “attempts a diagnosis of a disease that does not exist,” observing that “much miscellaneous grumbling on the part of some restless minds” does not necessarily demonstrate a decline in the quality of the modern pulpit (“Decay” 264). A critic for Christian Life took a more defensive stance, suggesting that Mahaffy’s insistence on the decline of preaching was based on a rising tide of public criticism: “There is undoubtedly more criticism of the preacher now than ever there was before, but it is simply because more is expected from him. The average standard of intelligence in the pew is being raised, and hence arises the demand for a higher standard of intelligence and ability in the pulpit. And the demand is gradually being met” (“Function” 327). Perhaps the most striking response came from The Month, a Catholic journal that celebrated Mahaffy’s volume chiefly because it rehearsed some of the most popular arguments against Anglican preaching circulating within Roman Catholic circles. If the dogmatic sermon is “a source of endless difficulty for the Anglican clergyman,” the reviewer declared, it is a source of enrichment for the Catholic worshipper “because of our unswerving, most definite, and clearly defined faith” (“Why Men Do Not Preach Well” 295).

Overwhelmingly, critics responded to Mahaffy by suggesting that preaching was not in fact a declining art and pointing to Victorian evangelical culture as evidence of this claim. Yet Mahaffy was not entirely alone in his concern for the state of Victorian preaching. Austin Phelps, for one, had made very similar claims in Preaching: What to Preach, and How to Preach, published the very same year. In Phelps’s view, “The complaints commonly made respecting the inferior quality of many of the sermons delivered from Church of England pulpits will be a sufficient justification for the appearance of this volume” (v). Indeed, countless works were published at the same time calling for a renewed attention to the art of preaching, and many of these garnered more positive reviews than Mahaffy’s volume, despite his elevated reputation. One reason for this is postulated by a critic for The Church of English Pulpit and Ecclesiastical Review, in a notice that is for the most part admiring of Mahaffy’s arguments:

The book should have ended with a few eloquent sentences on the nobility and glory of preaching for Christ; not because such sentences would have been strictly within the scope of the book, but rather to show that Mr. Mahaffy himself appreciates the momentous nature, and the spiritual responsibilities, and the splendid possibilities of the preacher’s office. One glimpse into his inner feelings on religion would have helped to conciliate many to his views of preaching merely as an art. The book wants a spiritual climax. (“Reviews and Notices” 156)

Given Mahaffy’s unremitting focus on the value of intellect and rhetoric in The Decay of Modern Preaching, this reviewer suggests, it is rather striking that he neglects to project the ethos of a man who regarded faith as a matter of great personal value. Focusing largely on the outward forms of religious expression, Mahaffy led some readers to think that these were the only expressions of faith he understood.

The publication of Mahaffy’s The Decay of Modern Preaching constituted a critical turning point in the public reputation of an important figure in late Victorian intellectual, political, and institutional life. Seen within its proper historical context, however, we can begin to reassess Mahaffy’s role in shaping the landscape of late Victorian intellectual culture—especially the crucial intersections of spirituality and aesthetics that have been seen as a keynote of the period. Moreover, we might understand Mahaffy’s work as an illustration of the challenges of navigating an intellectual landscape in which religion was not waning in influence but instead continued to play a vital political and cultural function, which did not always neatly align with expressions of religious feeling.

The truth or falsity of Mahaffy’s argument regarding the quality of nineteenth-century preaching may ultimately be less important than what the larger debate regarding the power of the pulpit tells us about the challenges of navigating between political, intellectual, and religious discourse at this time. Mahaffy’s capacity for relating past and present was a hallmark of his career. The Oxford and Cambridge Review hailed his “easy sympathy of approach to the modern mind” (“What Have the Greeks Done” 130). As one account puts it, “His revelation of the same human nature linking the world of two thousand years ago to the world of the present day, has earned for his Greek studies deserved popularity” (“John Pentland Mahaffy.” Warner Library 9570-1). But this historical sensibility—celebrated in the arena of scholarship—remained controversial among theologians, some of whom considered it heresy.[15] For his own part, Mahaffy seems to have dwelled very little upon such charges. Just a few years following The Decay of Modern Preaching, he published a book on a completely different subject, The Principles of the Art of Conversation (1887). Lamenting the tendency of conversation to dwell upon such mundane topics as the weather, he made a provocative claim: “every sensible person should have some paradox or heresy” on hand in order to “make the people about him begin to think as soon as possible” (Principles 161). For Mahaffy, heresy had become a necessary condition of intellectual inquiry—and, paradoxically, of faith itself.

published January 2019

HOW TO CITE THIS BRANCH ENTRY (MLA format)

[Stern], [Kimberley, J]. “The Publication of John Pentland Mahaffy’s The Decay of Modern Preaching (1882).” BRANCH: Britain, Representation and Nineteenth-Century History. Ed. Dino Franco Felluga. Extension of Romanticism and Victorianism on the Net. Web. [Here, add your last date of access to BRANCH].

WORKS CITED

Brasol, Boris. Oscar Wilde: The Man, The Artist. London: Williams and Norgate Limited, 1938. Print.

Brown, James Baldwin. “Is the Pulpit Losing its Power?” The Nineteenth Century (March 1877): 97-112. Print.

Brown, Julia Prewitt. Cosmopolitan Criticism: Oscar Wilde’s Philosophy of Art. Charlottesville: U of Virginia P, 1997. Print.

“The Coming Crisis.” The Month 68 (April 1890): 457-73. Print.

Dale, Robert William. Nine Lectures on Preaching. New York: A.S. Barnes, 1878. Print.

“The Decay of Modern Preaching.” Baptist Quarterly Review 5.18 (1882): 264. Print.

Douglas, Alfred Lord. Oscar Wilde: A Summing Up. London: Duckworth, 1950. Print.

Ellison, Robert. The Victorian Pulpit: Spoken and Written Sermons in Nineteenth-Century Britain. Selinsgrove: Susquehanna UP, 1998. Print.

Ellmann, Richard. Four Dubliners. Washington: Library of Congress, 1986. Print.

———. Oscar Wilde. New York: Knopf, 1987. Print.

“Euripedes.” The Eclectic Magazine (January 1880): 121-22. Print.

“The Function of the Pulpit.” Christian Life (July 8 1882): 327. Print.

Gibson, William, ed. The Oxford Handbook of the British Sermon 1689-1901. Oxford: Oxford UP, 2012. Print.

Great Britain. House of Commons. Report of the Commission on Irish University Education, Sessional Papers 1. 31 1901. Print.

Hunter-Blair, David. In Victorian Days and Other Papers [1939]. Freeport: Books for Libraries, 1969. Print.

Irish, Tomás. “A Man Called Mahaffy: An Irish Cosmopolitan Confronts Crisis, 1899-1919.” Historical Research 89.246 (November 2016): 846-65.

“John Pentland Mahaffy.” Methodist Review 79 July 1919: 507-16. Print.

“John Pentland Mahaffy.”The Warner Library 16. New York: Knickerbocker Press, 1917. 9569-71. Print.

Mahaffy, John Pentland. Brief Summary of the Principal Stages of My Life. Manuscript Notebook. 1919. MS 11137. Trinity College Dublin, Manuscripts Department.

———. The Decay of Modern Preaching. London: Macmillan, 1882. Print.

———. Greek Life and Thought [1887]. London: G.P. Putnam’s Sons, 1910. Print.

———. Principles of the Art of Conversation. London: G.P. Putnam’s Sons, 1888. Print.

———. “The Romanisation of Ireland.” The Nineteenth Century 50 (July 1901): 30-43. Print.

———. Social Life in Greece. London: Macmillan, 1874. Print.

Judgment in the Case of the Rev. William Maturin. The Church Association Monthly Intelligencer 5-6 (1 October, 1872): 253-6. Print.

Mack, Burton L. Rhetoric and the New Testament. Minneapolis: Augburg Fortress, 1990. Print.

McCabe, Joseph. The Story of Religious Controversy. Boston: The Stratford Company, 1929. Print.

Murphy, Andrew. Ireland, Reading and Cultural Nationalism, 1790-1930. Cambridge: Cambridge UP, 2018. Print.

Newman, John Henry. “Intellect, the Instrument of Religious Training.” Sermons Preached on Various Occasions. London: Burn, Oates, and Company, 1874. 1-14. Print.

“Notices of New Books—The Decay of Modern Preaching.” The New Englander 41.5 (1882): 710. Print.

Oliphant Old, Hughes. The Modern Age, vol. 6 of The Reading and Preaching of the Scriptures in the Worship of the Christian Church. Grand Rapids: William B. Eerdmans Publishing Company, 2007. Print.

“Reviews and Notices.” The Church of England Pulpit and Ecclesiastical Review 13 (1882): 155-6. Print.

Robson, Julie-Ann. “The Time of Opening Manhood: Mahaffy, Wilde, and Pater.” Hungarian Journal of English and American Studies 10.1-2 (2004): 299-310.

Ross, Iain. Oscar Wilde and Ancient Greece. Cambridge: Cambridge UP, 2012. Print.

Stanford, William Bedell, and Robert Brendan McDowell. Mahaffy: A Biography of an Anglo-Irishman. New York: Routledge and Kegan Paul, 1971. Print.

Trumbull, Henry Clay. “From Professor Dr. John P. Mahaffy.” The Threshold Covenant or the Beginning of Religious Rites. New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1896. 314. Print.

Webb, Daniel. “Religious Controversy and Harmony a Trinity College Dublin over Four Centuries.” Hermathena (1992): 95-114. Print.

“What Have the Greeks Done for Modern Civilization?” The Oxford and Cambridge Review 7 (1909): 129-130. Print.

“Why Men do not Preach Well.” The Month 45.216 (June 1882): 295-7. Print.

Wilde, Oscar. Complete Letters of Oscar Wilde. Eds. Merlin Holland and Rupert Hart-Davis. New York: Henry Holt and Company, 2000. Print.

———. “The Rise of Historical Criticism.” Vol. IV of The Complete Works of Oscar Wilde. Ed. Josephine Guy. Oxford: Oxford UP, 2007: 3-70. Print.

ENDNOTES

[1] Given the prominent role Mahaffy played in Irish politics, educational policy, and historical scholarship of the late nineteenth century, the scarcity of modern research on his work is striking. The most detailed discussions of Mahaffy’s work in recent years have appeared in scholarship on Oscar Wilde. See for instance, Julie-Ann Robson, “The Time of Opening Manhood: Mahaffy, Wilde, and Pater.” Hungarian Journal of English and American Studies 10.1-2 (2004): 299-310. Occasionally, Mahaffy’s name is invoked in discussions of Victorian Hellenism, and Tomás Irish has explored the closing years of Mahaffy’s life in “A Man Called Mahaffy: an Irish Cosmopolitan Confronts Crisis, 1899-1919.” Historical Research 89.246 (November 2016): 846-65. Nevertheless, the only monograph examining his life and work remains William Bedell Stanford and Robert Brendan McDowell’s Mahaffy: A Biography of an Anglo-Irishman (New York: Routledge and Kegan Paul, 1971).

[2] See Lord Alfred Douglas, Oscar Wilde: A Summing Up (London: Duckworth, 1950), 52. Stanford and MacDowell speculate that Mahaffy’s own views may be reflected in the following passage from The Social Life of Greece: “It was not the faith of mystics, nor an absorption of the mind in the contemplation of Divine perfections and Divine mysteries, but rather the religion of a shrewd and practical people, who [. . .] blessed God, not like Fénelon, because he was ideally perfect, but like Bossuet, because they received from him many substantial favours” (143).

[3] Ludwig Feuerbach’s 1841 volume The Essence of Christianity contended that God and religion were merely the outward manifestations of natural human impulses and that, therefore, any belief in spiritual powers external to man were misguided. Ernest Renan’s Life of Jesus (1863), much like Strauss’s volume, treated Christ as a historical figure, notably claiming that his emergence as a religious icon depended upon abandoning his Jewish roots.

[4] To regard Wilde as a champion of hedonistic excess is, of course, a gross oversimplification of his work, which engages rigorously with questions of moral import. An especially rich discussion of Wilde’s relationship to ethics can be found in Julia Prewitt Brown, Cosmopolitan Criticism: Oscar Wilde’s Philosophy of Art (Charlottesville: U of Virginia P, 1997).

[5] This is despite the fact that Wilde surely had already encountered Hellenic culture at Portora Royal School, as noted by Iain Ross in Oscar Wilde and Ancient Greece (Cambridge: Cambridge UP, 2012). Nevertheless, Mahaffy’s role in shaping Wilde’s encounters with Greek culture was significant. The origin of Mahaffy’s reputation as a pagan sympathizer likely originates in his remark to Wilde: “we cannot let you become a Catholic but we will make you a good pagan instead” (Ellmann, Oscar Wilde 67). Richard Ellmann is careful, however, to take the remark with tongue in cheek, noting that Mahaffy was more “arch-Protestant” than agnostic (Ellmann, Four Dubliners 18).

[6] George Macmillan records on 28 March 1877 that “Mahaffy is quite determined” to prevent Wilde’s seeing “all the glories of the religion which seems to him the highest and most sentimental.” On 27 April, Wilde would confirm in a letter: “I never went to Rome at all! […] but Mahaffy my old tutor carried me off to Greece with him to see Mykenae and ![]() Athens” (Complete Letters 44).

Athens” (Complete Letters 44).

[7] An especially sharp response to Mahaffy’s hostility toward the Catholic University can be found in “The Coming Crisis.” The Month 68 (April 1890): 457-73.

[8] An account of the trial and verdict can be viewed in The Church Association Monthly Intelligencer 5-6 (1 October, 1872): 253-6.

[9] For an exceptionally detailed overview of Trinity College Dublin’s religious history see, Daniel Webb, “Religious Controversy and Harmony a Trinity College Dublin over Four Centuries.” Hermathena (1992): 95-114.

[10] Newman reportedly left his post at the Catholic University because he, like Mahaffy, felt that it had been deployed as a political tool rather than as an educational enterprise.

[11] See, for instance, the work of Robert Ellison, who notes that the pulpit’s “decline” was very much a subject for debate in Robert Ellison, The Victorian Pulpit: Spoken and Written Sermons in Nineteenth-Century Britain (Selinsgrove: Susquehanna UP, 1998), 51.

[12] For a detailed discussion of the rise in literacy in nineteenth-century Ireland, see Andrew Murphy, Ireland, Reading and Cultural Nationalism, 1790-1930 (Cambridge: Cambridge UP, 2018.)

[13] While it is clear that he was consuming Catholic sermons both in person and in print from the 1850s well into the latter part of the century, we cannot definitively establish that Mahaffy attended this sermon and, to my knowledge, no record of Mahaffy’s having read Newman’s sermons remains.

[14] In practice, the extent to which preachers were trained in rhetoric varied widely depending on their educational background, though Burton Mack observes that rhetoric as an object of study at the university was in general decline for much of the century; see Burton L. Mack, Rhetoric and the New Testament (Minneapolis, Augburg Fortress, 1990). For his own part, Mahaffy draws a distinction between the kind of rhetoric that students of Trinity College Dublin would have encountered (for instance, Aristotle’s Logic) and the study of applied rhetoric, that is, he regarded the historical study of rhetoric as fundamentally different from an awareness of how to deploy rhetorical techniques as the author of a sermon.

[15] Mahaffy’s oft-repeated belief that the “Greeks were the fathers of modern thinking” directly informed the work of his most famous pupil, Oscar Wilde, who would remark in “The Rise of Historical Criticism” that the “Greek spirit is essentially modern.” J.P. Mahaffy, Greek Life and Thought [1887] (London: G.P. Putnam’s Sons, 1910), 225; Oscar Wilde, “The Rise of Historical Criticism.” vol. IV of The Complete Works of Oscar Wilde. Ed. Josephine Guy (Oxford: Oxford UP, 2007), 3-70, 66.