Abstract

Prior to political agitation for the reform of married women’s property laws, nineteenth-century fiction emphasized primogeniture (the common law doctrine of consolidating wealth in the hands of eldest sons) alongside coverture (the common law doctrine that marriage voided a wife’s separate legal identity) in order to show how both contributed to women’s economic marginalization. The reform movement, however, focused its attention on coverture, and by the time of the 1870 Act, fiction begins to divorce its sympathy for women’s subjugation in coverture from its treatment of women’s condition with respect to primogeniture. This case study of novels by Jane Austen and George Eliot suggests that, as coverture comes under closer scrutiny, primogeniture is no longer showcased as one of women’s most significant economic disadvantages. Instead, the claims of primogeniture begin to appear as an argument against women’s rights to property.

Women’s lack of educational and professional opportunities throughout much of the long nineteenth century prevented them from acquiring or controlling much wealth, but their marginal economic status was exacerbated by two common law doctrines: primogeniture and coverture. The first overwhelmingly passed over daughters’ rights of inheritance in favor of an eldest son’s, compelling many to secure their social status and subsistence through marriage; the second denied wives economic agency within such marriages. A series of Married Women’s Property motions and Acts would attempt to redress the latter doctrine of coverture in practice by granting a married woman the legal status of a single woman (“feme sole”). These laws attempted to address the problems with coverture independently of any perceived problems with primogeniture, but throughout the century fictional treatments linked the two, to different ends.

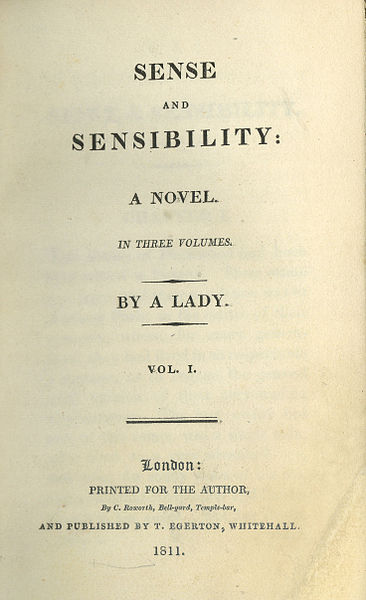

During the early part of the century, literary depictions tied coverture to the economic marginalization brought about by primogeniture to suggest that the combination of the two was the real obstruction to women’s fortunes. If, as Mary Lyndon Shanley and others have observed, legal movements for married women’s property rights gained momentum through a desire to protect women from greedy, negligent, or abusive husbands, fictional accounts by Jane Austen suggested that, if women required protection, they needed it from their birth families as much as from their husbands. Ruth Perry has argued that the early part of this period saw “the basis of kinship” shift from an emphasis on blood lineage to that of conjugal ties (2), with significant economic consequences for women. Daughters of the landowning classes received diminished inheritances and settlements as families sought to secure wealth for eldest sons, while daughters of working families faced reduced access to their means of subsistence as large estates were consolidated.[1] Although revisionist studies have argued that daughters received more in practice than the common law dictated,[2] fictional representations of inheritance often perpetuate the image of unequal distribution. Many of Austen’s heroines, dependent upon marriage because their father’s homes and wealth are entailed upon a brother or male cousin, have typified this plight. Elinor, Marianne, and Margaret Dashwood of Sense and Sensibility (1811), for instance, do not benefit from their father’s inheritance of a considerable estate because it has been secured to their elder half-brother, John Dashwood, increasing his already considerable income by “four thousand a-year” (7) while a flat sum of 10,000 pounds will provide the total income and fortune of three once extremely well-to-do sisters and their mother. In Pride and Prejudice (1813), Jane and Elizabeth Bennet similarly lack fortunes because their father’s estate “was entailed, in default of heirs male, on a distant relation” (19). The unlikeable nature of the heirs make their fortunes appear particularly unfair; the fact that Pride and Prejudice’s heir Mr. Collins acts as the foolish mouthpiece for the one-flesh doctrine of coverture—claiming, against all evidence to the contrary, that his wife and he “have but one mind and one way of thinking” (142)—aligns the two faulty doctrines.[3]Support for women’s rights to property comes, at this point in literary history, in relation to primogeniture as much as coverture, despite the emphasis on legal reform for the latter during the second half of the century.[4] In both of these novels, the daughters’ inheritance has direct bearing on the necessity of marriage and the difficulty of finding a suitable match, but if these daughters require “protection,” it would seem to be as much from their birth families as from any husbands; Mr. Bennet and Mr. Dashwood fail to provide adequately for their daughters, not simply because the legal situation of entailed estates is out of their hands, but because they are not very good at saving. “Mr. Bennet had very often wished . . . that, instead of spending his whole income, he had laid by an annual sum, for the better provision of his children, and of his wife, if she survived him. He now wished it more than ever” (199-200). Mr. Dashwood, too, despite his best intentions of “living economically” in order to “lay by a considerable sum” for his wife and daughters, dies before managing to do so (6).[5]

Although, as historians and literary critics have demonstrated, primogeniture—particularly among the middle classes—was never absolute,[6] the general preference for endowing male lineage meant that marriage was an important source of financial security for women, even as women conscious of this financial motivation were depicted as selling themselves for an establishment.[7] Yet even the financial security of such women was incomplete.[8] Under the common law doctrine of coverture, a woman’s money and other property passed to her husband at marriage: wives could not inherit, bequeath, or earn separate property, nor could they enter into contracts without their husbands’ consent.[9] As Rachel Ablow’s BRANCH entry, “‘One Flesh,’ One Person, and the 1870 Married Women’s Property Act,” notes, coverture essentially entailed the disappearance of a wife’s separate legal identity in marriage, presumably making the couple “one flesh.” This doctrine “covered” her debt or legal infractions, yet, despite the dubious advantage of this legal “protection,” coverture also stripped a wife of economic agency. All earnings, inheritance, personal property, or land owned at the time of her marriage or acquired after that point became the property of her husband.[10]

Women and their supporters fought coverture on multiple fronts. The Petition for Reform of the Married Women’s Property Law, which was presented in 1856 and included twenty-six thousand signatures, began the joint effort by lawmakers and public women to grant married women legal control over their own wealth and earnings, finally achieved in part by the Married Women’s Property Acts of 1870 and 1882 (Shanley 33).[11] Other women benefited from the separate estates set up in trust for them in courts of equity (Shanley 15, 25). And, as Margot Finn and others have shown, still more women found degrees of economic agency through family businesses and legal practices such as the law of necessaries and strategic uses of credit.[12] Such strategies meant that, long before legal reforms were instituted, ways of securing property rights and economic agency for married women outside of the common law were being imagined. For the most part, however, these practical efforts to ameliorate women’s economic status ignored the interconnectedness of the two common law doctrines that fiction such as Austen’s united, one emphasizing the financial ramifications of marriage, the other emphasizing the financial ramifications of birth.

In addition to receiving his father’s inheritance, Sense and Sensibility’s John Dashwood benefits from his own mother’s property, apparently secured to her as her separate estate. He “was amply provided for by the fortune of his mother, which had been large, and half of which devolved on him on his coming of age” (5); the other half of his mother’s wealth would also be his because it “was also secured to her child, and [her husband, John’s father] had only a life interest in it” (6). On the one hand, John’s mother’s wealth is evidence of the safeguards already put into place for protecting (some) married women’s property even before the legal reforms of the later century. His father did not have access to the principle of his mother’s money, only its interest during his own lifetime. Despite the claims of coverture, her marriage did not merge her property with his—an example of the kind of trusts established for wealthy women outside of the court of common law, and, in its evasion of the common law, something of an argument against it.

Yet this protection of the late Mrs. Dashwood’s property ultimately seems less a triumph for the wife than for her son, whose father, we learn, would have been very pleased to ignore the custom of primogeniture and divide the wealth with his three less privileged female children instead. The narrative emphasis on those children—whose fortunes and marriage plots occupy the rest of the novel—also diminishes any sense that this episode reflects a feminist victory or even a real disruption of the common law. As Cheri Larsen Hoeckley has argued, “equity settlements often simply allowed a father to preserve family property . . . for future male heirs” (149).[13] Thus even a wife’s “separate estate” here ultimately serves the purpose of primogeniture. The novel’s discussion of inheritance reminds readers that the doctrines of primogeniture and coverture—the economics of birth and marriage—work hand in hand to limit women’s financial options and suggests that addressing one independently of the other will not effectively secure property to women.

Coverture and primogeniture again join hands as John Dashwood’s wife, Fanny, directs his interests in favor of their son. On the one hand, she appears to have a kind of economic agency through him, in keeping with the theory behind the “one-flesh” doctrine of coverture. She “did not at all approve” of her husband’s initial intention to provide for his half-sisters, and her “consent to this plan”—which she refuses to give—seems necessary to it. As she persuades him to reduce the gift from his initial thought of three thousand pounds to “sending presents of fish and game, and so forth, whenever they are in season” (12), she effectively manages both her husband and his finances and, as Elsie B. Michie’s study of rich women in fiction has shown, becomes the scapegoat for self-interested wealth as she “reveals the engrossment of her personality by incrementally teaching her husband to think of wealth as something that must be engrossed” (28).[14]

Fanny’s manipulation is painted as despicable not because she is able to influence her husband’s decision but because of the selfishness of her views. Coverture—that merging of economic and less-material interests alike—seems to affect both husband and wife here by shaping the spouses’ personalities. As the narrator informs us: “Had [John Dashwood] married a more amiable woman . . . he might even have been made amiable himself” (7). As Michie has shown, Austen invites us to demonize this wealthy woman.[15] Yet, in a “more amiable woman,” Fanny’s own narrow maternal anxiety for her child’s interests might actually have aligned her with the mother of her disinherited half-sisters-in-law, whose love of her own children similarly obscures her own vision of the world. Through coverture, Fanny has no more legal power over the situation than they do, resorting to “begg[ing],” “argu[ing],” and “point[ing] out” her perspective, because ultimately, “the question is, what [he] can afford to do” (10), not what she wishes him to do, nor what is in either her best financial interest or her son’s. Her desire to enrich her own son by consolidating various fortunes in his hands—“How could he answer it to himself to rob his child, and his only child too, of so large a sum?”(9)—is not so different from the general custom of enriching male heirs. Whereas her husband benefited from his mother’s “separate estate,” Fanny Dashwood cannot make any legal claim upon her husband’s recent inheritance, not even for the benefit of her son. Instead, she is forced to rely on her husband’s sense of honor and duty to prevent him from “rob[bing] his child.” She is the daughter “of a man who had died very rich” (14), and while we learn later that she received ten thousand pounds upon her marriage (264), her father also had an “eldest son,” who—at least at this early point in the story—seems likely to inherit the largest part of the family wealth. Despite her apparent greed, her unkindness to her half sisters stems from those same joined common law doctrines of primogeniture and coverture that shaped their fortunes. The implication is that both sympathetic and unsympathetic characters would be better off—and perhaps even more generous—under different legal conditions.

Later in the century, after the Divorce Act of 1857 placed coverture under increasing scrutiny, legislators emphasized their duty to protect women within marital relationships (thus ensuring the smooth functioning of coverture), rather than advocate for their equal rights (which would rupture the fiction of coverture altogether) (Shanley 71-4, 77-8). Along these lines, the Married Women’s Property Act of 1870, which gave wives control of their earnings and of legacies under £200, was seen as protecting women of the working or lower-middle classes rather than securing independent property rights for the wealthier classes described by Austen. Despite its limited reach, however, the cultural anxieties attending this law were as great as if it had done much more. (See again Rachel Ablow’s “‘One Flesh,’ One Person, and the 1870 Married Women’s Property Act” for a discussion of the law’s effect on ideas of marriage itself.) In fiction written after 1870, we find women whose marriages secure them great wealth but whose claims to that wealth appear to conflict with the claims of their husbands’ first-born sons. That is, problems of coverture and primogeniture again appear together, but to different effect: once wives can claim property as their own, primogeniture becomes as much a reason to withhold that property as a reason to grant it.

Wives’ claims to property in late-century writing are not all, strictly speaking, governed by coverture or its dissolution. Although that common law doctrine had previously ensured that a wife’s property would become her husband’s after marriage, it significantly did not ever ensure the opposite, that a husband’s property would become her own. On the contrary, only through a husband’s conscious legal action could it be so. Yet the new legal precedent of recognizing a wife’s claim to any property within marriage appears, for some writers, tantamount to a wife’s claiming all property within marriage. That is, after the Married Women’s Property Act of 1870 weakened the doctrine of coverture as absolute, a wife’s independent possession of property begins to be represented as theft. Along these lines, mercenary marriage becomes problematic not simply for what it suggests about the gold-digging wife or the institution of marriage itself but because it enables a wife wrongfully to take what should be her husband’s or son’s wealth and make it her “own.” Fictional wives and widows are faulted for claiming as their “own” property that the novel assigns to their husbands’ sons.

Coverture itself, the fiction that marriage creates any real accord, continues to appear injurious in the wake of the 1870 Act. In George Eliot’s Daniel Deronda (1876), for instance, which will be the case study for the rest of my argument, Gwendolen’s marriage is characterized by her husband’s “imperiousness” (427), their “struggle” for dominance (426), and the absence of any of the marital unity presumed by the “one-flesh” doctrine: “How . . . could Grandcourt divine what was going on in Gwendolen’s breast?” (671). Eliot suggests that this sympathetic impasse—the realist novel’s counterpoint to coverture’s more ideal conditions—is matched by financial disparity. Gwendolen acknowledges that she “must leave . . . to Mr Grandcourt” all economic questions; with no control over the family wealth herself, she is “very anxious to have some definite knowledge of what would be done for her mother” after her marriage, and experiences “a sense of obligation” when she learns, after the fact, that he has chosen to provide for her (428).

Yet Daniel Deronda features the economic concerns of marriage alongside those of inheritance not simply to reveal the double-edged marginalization of women, which we saw earlier in the century, nor to express the mercenary side of matrimony,[16] but to stage a debate about the relative rights of a wife and a son. When Grandcourt’s former mistress confronts Gwendolen to prevent her marriage because “[Grandcourt] ought to make [their] boy his heir” (152), the novel takes seriously her chief objection to the marriage, that “my boy [not be] thrust out of sight for another” (152). Gwendolen, too, responds to the matter of the child’s inheritance with feelings of remorse and generosity: “Perhaps we shall have no children. I hope we shall not. And he might leave the estate to the pretty little boy” (314). Indeed, Gwendolen is “reduced to dread lest she should become a mother” (672-3) at least in part for this reason. At the same time, however, as soon as she has been married, she revels in the thought of personally acquiring new wealth, excited—despite the perceived injustice of it—at “having her own” luxury items (358).

The novel pits the wife’s right to property (however acquired) against that of a son, and the son wins out. Illegitimacy gives this son no more legal claim to the estate than Gwendolen.[17] But after Grandcourt’s death, when this son inherits nearly all of his father’s wealth, his illegitimacy is a nonissue. The reinstated heir looks like his father, acquires most of his wealth, and takes his name.[18] It’s a progressive treatment of illegitimacy not to punish the child for his parents’ actions, but by the time the affair has been settled, it’s hardly a treatment of illegitimacy at all. The issue of legitimacy (mistress versus wife, bastard versus bride) thus takes a backseat to the novel’s question of whether a wife’s or a son’s claim to property should take precedence. As an answer, it makes a wife’s wealth—Gwendolen’s initial idea that any property—even or especially her husband’s—could become her “own” after marriage (358)—appear as theft.[19] Even Gwendolen’s well-wishers support the son’s right of inheritance, remarking that “since the boy is there, this was really the best alternative for the disposal of the estates” (757). Deronda, the moral center of the novel, goes so far as to say that “[Grandcourt] did wrong when he married this wife—not in leaving his estates to the son” (716). And Gwendolen herself is “quite contented with it” (717), calling the decision “. . . all perfectly right” (759) and expressing relief that she is “saved from robbing others” (699). Nobody argues that a wife should have greater claim to property than a son. By representing Gwendolen’s marital wealth as illicit, the novel suggests that a wife’s property, whether accrued before, within, or after marriage, is less legitimate than property transmitted to even an illegitimate son.[20]

These arguments had serious stakes in 1876, when political agitation for wives’ rights to hold their “own” property had made some progress but was still underway. A fuller recognition of women’s economic rights within marriage would come shortly, with the Married Women’s Property Act of 1882. But at this time of intense debate about property rights, the novel’s putative “crime” and its resolution—representing a wife’s wealth as theft and then saving her from “robbing others” by restoring it to a male heir—suggests that when wives claim property as their “own” they do so at the expense of sons and with no real benefit to themselves. In contrast with Austen’s novels, where a son’s privileged inheritance is a fundamental cause of mercenary marriage and a contributing factor to women’s poor economic standing, here instead such inheritance is offered as the lesser evil in the face of women’s increasing claims to wealth within marriage.

At the same time, however, the fact that this son’s claim to his wealth depends upon the whim of an unlikeable man and the “absence of a legitimate heir” (757) rather than the common law doctrine of primogeniture, reminds us of little Grandcourt’s own problematic claims to ownership; similarly, Gwendolen’s claims to her “own” property within marriage are supported neither by coverture nor by the Married Women’s Property Act of 1870. Each case reflects the inadequacy of contemporary law to allocate possession in a way that suits social feeling. The novel’s depiction of women’s stinted economic autonomy before, within, or without marriage—Gwendolen’s step-father having “carried off his wife’s jewellery and disposed of it” (274-5), for instance—similarly suggests greater sympathy for women’s restricted options and the need for other conceptions of marriage than “coverture,” a concept that repeatedly fails to veil the sharp differences between husbands and wives in the novel.[21] Unwilling to allow women to profit within marriage by claiming wealth as their “own,” the novel is nonetheless adamant that marriage itself is an institution in need of reform. When Grandcourt drowns, accidentally thrown overboard, Gwendolen’s guilty conscience at having wanted to “kill him in my thoughts” (695) and neglecting to toss him the rope (696) fails to incriminate her. Discovered in tears, on her knees, “Such grief seemed natural in a poor lady whose husband had been drowned in her presence” (702); the “cover” of marriage effectively absolves her of any wrongdoing.

HOW TO CITE THIS BRANCH ENTRY (MLA format)

published July 2012

Rappoport, Jill. “Wives and Sons: Coverture, Primogeniture, and Married Women’s Property.” BRANCH: Britain, Representation and Nineteenth-Century History. Ed. Dino Franco Felluga. Extension of Romanticism and Victorianism on the Net. Web. [Here, add your last date of access to BRANCH].

WORKS CITED

Ablow, Rachel. “‘One Flesh,’ One Person, and the 1870 Married Women’s Property Act.” BRANCH: Britain, Representation and Nineteenth-Century History. Ed. Dino Franco Felluga. Extension of Romanticism and Victorianism on the Net. Web. 28 Jun. 2012.

Austen, Jane. Pride and Prejudice. Ed. Donald Gray. New York: Norton, 2001. Print.

—. Sense and Sensibility. Ed. Claudia L. Johnson. New York: Norton, 2002. Print.

Bailey, Joanne. “Favoured or Oppressed? Married Women, Property, and ‘Coverture’ in England, 1660-1800.” Continuity and Change 17.3 (2002): 351-72. Print.

Bodichon, Barbara Leigh Smith. “A Brief Summary, in plain language, of the most important laws concerning women: together with a few observations thereon.” 1854. Victorian Women Writer’s Project. Bloomington: Indiana U, 2012. Web. 29 Jun. 2012.

Eliot, George. Daniel Deronda. Ed. Terence Cave. London: Penguin Books, 1995. Print.

Erickson, Amy Louise. Women and Property in Early Modern England. London: Routledge, 1993. Print.

Finn, Margot. “Women, Consumption and Coverture in England, c. 1760-1860.” The Historical Journal 39.3 (1996): 703-722. Print.

Hoeckley, Cheri Larsen. “Anomalous Ownership: Copyright, Coverture, and Aurora Leigh.” Victorian Poetry 35.2 (1998): 135-61. Print.

Holcombe, Lee. Wives And Property. Toronto: U of Toronto P, 1983. Print.

Michie, Elsie B. The Vulgar Question of Money: Heiresses, Materialism, and the Novel of Manners from Jane Austen to Henry James. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins UP, 2011. Print.

Osborne, Katherine Dunagan. “Inherited Emotions: George Eliot and the Politics of Heirlooms.” Nineteenth-Century Literature 64.4 (2010): 465-493. Print.

Owens, Alastair. “Property, Gender and the Life Course: Inheritance and Family Welfare Provision in Early Nineteenth-Century England.” Social History 2:3 (2011): 299-317. Print.

Perry, Ruth. Novel Relations: The Transformation of Kinship in English Literature and Culture 1748-1818. Cambridge: Cambridge UP, 2004. Print.

Psomiades, Kathy. “Heterosexual Exchange and Other Victorian Fictions: The Eustace Diamonds and Victorian Anthropology.” NOVEL: A Forum on Fiction 3.1 (1999): 93-118. Print.

Rappaport, Erika Diane. Shopping for Pleasure: Women in the Making of London’s West End. Princeton: Princeton UP, 2000. Print.

Rappoport, Jill. Giving Women: Alliance and Exchange in Victorian Culture. New York: Oxford UP, 2011. Print.

Ruoff, Gene. “Wills.” 1992. Sense and Sensibility. Ed. Claudia L. Johnson. New York: Norton, 2002. 348-359. Print.

Shanley, Mary Lyndon. Feminism, Marriage, and the Law in Victorian England. Princeton: Princeton UP, 1989. Print.

Staves, Susan. Married Women’s Separate Property in England, 1660-1833. Cambridge: Harvard UP, 1990. Print.

Vickery, Amanda. “Golden Age to Separate Spheres? A Review of the Categories and Chronology of English Women’s History.” The Historical Journal 36.2 (1993): 383-414. Print.

RELATED BRANCH ARTICLES

Rachel Ablow, “‘One Flesh,’ One Person, and the 1870 Married Women’s Property Act”

Kelly Hager, “Chipping Away at Coverture: The Matrimonial Causes Act of 1857″

Anne D. Wallace, “On the Deceased Wife’s Sister Controversy, 1835-1907″

[1] Ruth Perry, Novel Relations (see esp. 64, 2, 24, 34, 40, 47, 212-3).

[2] See Alastair Owens, “Property, Gender and the Life Course” (313-4). Owens notes, however, that daughters’ inheritances should “not be overstated,” since wives and widows typically lacked control over property (307-10). Also writing against the bleak narrative of women’s diminished property ownership, Amanda Vickery finds “no systematic reduction in the range of employments available to laboring women” (405).

[3] As Elsie B. Michie has noted recently in The Vulgar Question of Money, Austen’s novels resist the notion that either inheritance or marriage should assist in one individual’s extreme accumulation of wealth (1-2, 28-9).

[4] Lady Catherine de Bourgh’s one moment of something like sympathy toward Elizabeth Bennet comes when she notes that “I see no occasion for entailing estates from the female line” (Pride and Prejudice 109).

[5] Their failure to provide legally for their children would have been seen as “‘culpable,’” according to findings by Owens, who has argued that early nineteenth-century “married male property owners were under an obligation to provide for their family” through wills (303-4); the cultural emphasis on “providing” for kin (rather than simply disposing of an estate) makes Mr. Bennet’s belated regret for his failure seem particularly weak.

[6] See, for example, Amy Louise Erickson, Women and Property in Early Modern England (26, 78, 224); Owens (313-4); Jill Rappoport, Giving Women (e.g. 46, 50).

[7] For Kathy Psomiades, “the great paradox of the idea of heterosexual exchange is that it describes with greater and greater clarity woman’s position as circulated sign and commodity at precisely the historical moment in the West in which middle-class women and men to a greater and greater extent are seen as having a claim to equal economic and political agency” (94).

[8] For a classic contemporary response to coverture, see Barbara Leigh Smith Bodichon, “A Brief Summary, in plain language, of the most important laws concerning women: together with a few observations thereon” (1854).

[9] See Mary Lyndon Shanley, Feminism, Marriage, and the Law in Victorian England (passim, e.g. 8, 26, 66); also Susan Staves, Married Women’s Separate Property in England, 1660-1833 (27-36, 129-30, 217) and Lee Holcombe, Wives And Property. As Owens notes, “even in widowhood married women’s rights to family property were largely determined by their dead husband” (312).

[10] Hence Mr. Darcy’s alarm that his sister’s inheritance could have become the property of the fortune hunter Mr. Wickham (133); had they eloped as planned, no marriage settlements could have been made to protect Miss Darcy’s wealth. The fact that Elizabeth helps her own sister (Lydia Wickham) “by the practice of what might be called economy in her own private expenses” (253)—that is, through sharing her pin money, rather than tapping the household expenses—again reiterates that, under coverture, his larger wealth is not precisely her own.

[11] For details on the two Acts, see chapters two (49-78) and four (103-30); Holcombe (237-38 for petition, 243-246 for the 1870 Married Women’s Property Act, and 247-252 for the 1882 Act).

[12] Margot Finn, “Women, Consumption and Coverture in England, c. 1760-1860” (706, 707); Erika Diane Rappaport, Shopping for Pleasure: Women in the Making of London’s West End (50-65); Joanne Bailey, “Favoured or Oppressed?”; Erickson (150, 224).

[13] In a similar vein, Owens has noted that even widows “were rarely able to derive much financial benefit from family property,” since they were typically treated as custodians of their children’s future inheritance (310).

[14] See also Gene Ruoff’s discussion of Fanny’s own “will” with respect to the novel’s treatment of inheritance (esp. 350-353).

[15] Michie discusses the nineteenth-century history and legacy of this demonization. (For the specific example of Fanny Dashwood, see 27-29.)

[16] Along these lines, it seems significant that Gwendolen, unlike Austen’s Fanny Dashwood and the other wealthy women Michie discusses, is actually the “poor” woman when she marries Grandcourt; her poverty does not entail any of the virtues that nineteenth-century novels of manners often afforded the poor heroines chosen by wealthy husbands.

[17] Even marriage to Lydia Glasher would not have legitimated her son post-facto. Grandcourt could choose to make him the heir—and his marriage to Lydia would ensure the absence of any subsequent legitimate heirs—but in the case of intestacy, illegitimate children would have been passed over.

[18] Gwendolen Grandcourt will even share her name with the reinstated heir. Katherine Osborne notes that this renaming “throws any kind of traditional lineage into confusion” (789) but, since this renaming also conceals the heir’s illegitimate birth, we can also see it as a more traditional mandate to favor a son’s claims to property.

[19] To a certain extent, this is part of the scapegoating of wealthy women that Michie has discussed in nineteenth-century fiction, but—as I’ve noted—Gwendolen’s position differs from the examples Michie considers because she is not an heiress accumulating additional wealth through marriage.

[20] This decision is striking in part because it bequeaths wealth to a child who is still a minor; another option would have been for Grandcourt to establish a two-stage provision, allowing Gwendolen to benefit from the income of her late husband’s wealth until the heir was of an age to accept it. See Owens (305-7).

[21] In addition to the power struggles of Gwendolen’s marriage, the novel depicts other unhappy unions: Mirah’s mother, according to Mrs Meyrick, was “A good woman, you may depend: you may know it by the scoundrel the father is” (223); Deronda’s own mother describes herself as “forced into marrying your father” (626).