Abstract

This article presents the history and pre-history of Martin’s Act (1822), “Act to prevent the cruel and improper treatment of Cattle,” and the subsequent founding, in 1824, of the Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals (after 1840, the Royal Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals). It explains and analyzes the late-eighteenth-century and early-nineteenth-century context in which the animal welfare or anti-cruelty movement emerged. It also discusses the failed 1809 Act proposed by Lord Erskine and Richard Martin’s successful 1822 Act, and analyzes the particular role played by ridicule and shifting boundaries of humor in the discourse surrounding human treatment of animals.

The inauguration of the world’s first organized animal welfare movement can be dated to 1822 or 1824 in London, with the 1822 passing of the “Act to prevent the cruel and improper treatment of Cattle”—subsequently popularly known as Martin’s Act, after its sponsor, the Irish M.P. Richard Martin—and the 1824 founding of the Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals (SPCA). This particular moment was a culmination, however, of debates, arguments, and appeals that had steadily intensified throughout the previous century. “Throughout the eighteenth century,” Keith Thomas writes, “there was a growing stream of writing” in England on the subjects of the feelings or consciousness of animals and their proper treatment by human beings: “philosophical essays on the moral treatment of the lower creatures, protests about particular forms of animal cruelty and (from the 1780s) edifying tracts designed to excite in children ‘a benevolent conduct to the brute creation’” (149). Such sermons, tracts, and books as Humphry Primatt’s The Duty of Mercy and the Sin of Cruelty to Base Animals (1776), Thomas Young’s An Essay on Humanity to Animals (1798), and John Oswald’s The Cry of Nature; or an appeal to mercy and justice, on behalf of the persecuted animals (1791) exemplify the humanitarian, Evangelically-influenced culture of the late eighteenth-century Anglophone world, with its new valuation of sympathy for the socially or politically marginal or powerless. For at least some British thinkers and writers of the period, the post-revolutionary “Rights of Man” pointed the way logically to rights beyond man.

Such arguments against cruelty to or mistreatment of animals implied a challenge, however, to longstanding assumptions about “man”’s justified dominion over the natural world. As such, early claims for greater rights or dignities for animals in Great Britain were often greeted not only with anger and refutation but, strikingly, with a particular combination of disgust, outrage, and/or derisive or simply dismissive laughter. In 1772 in ![]() Oxfordshire, for example, the Rev. James Granger preached to his congregation against cruelty to animals, taking as his text Proverbs 12.10: “A righteous man regardeth the life of his beast: but the tender mercies of the wicked are cruel.” His remarks, as he explained in a postscript to the published version of his sermon, “gave almost universal disgust to two considerable congregations. The mention of dogs and horses, was censured as a prostitution of the dignity of the pulpit, and considered as a proof of the Author’s growing insanity” (Granger 27; also see Turner 72-73). As Harriet Ritvo observes, English law of this era “viewed animals simply as the property of human owners, only trivially different from less mobile goods” (2). Granger’s reference to his congregation’s sense of the “prostitution of the dignity of the pulpit” might lead one to speculate that the elevation of “dogs and horses” to subjects entitled to certain dignities or rights constituted an existential threat and a risk of contamination. Many key Enlightenment tenets and beliefs—e.g. Descartes’s doctrine of mind/body dualism—positioned the sovereign human subject as not just opposed to and different from the nonhuman animal but as constituted by that difference. To argue for the dignity of the animal was, in effect, to undermine or diminish the dignity of the human. Thus these two recurring forms of response: “disgust,” or, in a more confident mode, simple amusement or laughter at seemingly ludicrous transgressions of species hierarchies. “I once attempted to reason with a fellow . . . who was cruelly beating an innocent horse, till the blood spun from its nostrils,” wrote John Lawrence, a trainer and writer on horses, in 1796. “The reply I obtained was, ‘G— d— my eyes, Jack, you are talking as though the horse was a Christian” (Lawrence 140).

Oxfordshire, for example, the Rev. James Granger preached to his congregation against cruelty to animals, taking as his text Proverbs 12.10: “A righteous man regardeth the life of his beast: but the tender mercies of the wicked are cruel.” His remarks, as he explained in a postscript to the published version of his sermon, “gave almost universal disgust to two considerable congregations. The mention of dogs and horses, was censured as a prostitution of the dignity of the pulpit, and considered as a proof of the Author’s growing insanity” (Granger 27; also see Turner 72-73). As Harriet Ritvo observes, English law of this era “viewed animals simply as the property of human owners, only trivially different from less mobile goods” (2). Granger’s reference to his congregation’s sense of the “prostitution of the dignity of the pulpit” might lead one to speculate that the elevation of “dogs and horses” to subjects entitled to certain dignities or rights constituted an existential threat and a risk of contamination. Many key Enlightenment tenets and beliefs—e.g. Descartes’s doctrine of mind/body dualism—positioned the sovereign human subject as not just opposed to and different from the nonhuman animal but as constituted by that difference. To argue for the dignity of the animal was, in effect, to undermine or diminish the dignity of the human. Thus these two recurring forms of response: “disgust,” or, in a more confident mode, simple amusement or laughter at seemingly ludicrous transgressions of species hierarchies. “I once attempted to reason with a fellow . . . who was cruelly beating an innocent horse, till the blood spun from its nostrils,” wrote John Lawrence, a trainer and writer on horses, in 1796. “The reply I obtained was, ‘G— d— my eyes, Jack, you are talking as though the horse was a Christian” (Lawrence 140).

Utilitarianist claims about the central role of pain in calculations of happiness began to influence thinking about the suffering of nonhuman creatures in this period. As Jeremy Bentham famously wrote in 1781 about our moral consideration of animals, “the question is not, Can they reason? nor, Can they talk? but, Can they suffer?” Indeed, the process of changing the attitudes of those in Granger’s congregation, and their peers, depended less on reason than on extra-rational forms of persuasion. Although the congregationists’ belief in their reverend’s “growing insanity” now seems absurd, it is in fact the case that in this period some of the most influential briefs for animal rights or welfare emerged less in the form of reasoned argument than in visionary literary writing that sometimes challenged usual notions of the rational. As a young man, William Cowper experienced periods of insanity or mental breakdown, and attempted suicide more than once. Later, he became famous for sheltering elaborate animal menageries in his home, and in his great 1784 poem “The Task,” he celebrated a single pet hare, “[i]nnocent partner of my peaceful home,” that he saved from the hunt: “Well,—one at least is safe. One shelter’d hare / Has never heard the sanguinary yell / Of cruel man, exulting in her woes” (334-6). William Blake, too, was known both for his bouts of visionary madness and for his denunciations of human anthropocentrism and mistreatment of animals, as in (although this poem was not published until the Victorian period) “Auguries of Innocence”: “A horse misusd [sic] upon the Road / Calls to Heaven for Human blood. / Each outcry of the hunted Hare / A fibre from the Brain does tear” (11-14). The ideas of animal rights and of the possibility of an animal welfare reform movement were articulated and circulated with the freedom of imaginative license in late-eighteenth century Romantic and humanitarian literature before they began to move into legislation around the turn of the century. These ideas, perhaps, had to emerge first as flights of imaginative fancy, and be considered experimentally in that realm, before they could subsequently take form as law or policy.

The turn of the nineteenth century brought England’s first attempt at legislative action on behalf of animals, with unsuccessful 1800 and 1802 bills intended to outlaw bull baiting, supported by, among others, the Evangelical abolitionist William Wilberforce. Wilberforce’s involvement raises an association that may cause discomfort today, namely, that between the abolitionist or anti-slavery movements of the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries and the emergent anti-cruelty or animal welfare movement. Given the long history of racist thought associating non-whites or non-Europeans with animals, the link here may seem troubling, yet the historical and conceptual logics make sense. Romantic or revolutionary-era humanitarian thought challenged, on multiple fronts, previously-held Enlightenment and Christian assumptions about the primacy of “Man” presumed to be a universalized white male citizen. Whether in the form of feminism, working-class activism, abolitionism, or animal-welfare advocacy, these reform movements broadened the Rights of Man in expanded circles of rights or dignity. Clearly, the expansion of true rights to non-humans was a radical position (even in a radical age)—and not, it should be said, one advocated by all of those arguing in a welfarist mode for better treatment of animals in this era—but its logic was, arguably, internal to this larger expansion and rippling-outward of rights beyond the European, elite male subject.

After these failed early bills, the drive to legislation gained momentum. On 5 May 1809 a former Lord Chancellor known for progressive advocacy, Lord Thomas Erskine, gave a subsequently famous speech in Parliament arguing for England’s first prevention of cruelty to animals bill, one primarily designed to curb the beating and abuse of horses and cattle (entitled “An Act to prevent malicious and wanton Cruelty to Animals”). Erskine was far from demanding full rights or legal protection for horses; rather, “His Lordship distinguished between the dominion which man might justly exercise over the lower orders of the creation, for his sustenance and convenience”—“convenience,” especially, seeming an exceptionally flexible category here!—“And the duty, though one of imperfect obligation, which he lay under, of not abusing that power so as to put the animals under his protection to unnecessary pain” (London Times 16 May 1809). Erskine’s bill was defeated at the committee stage, however, due in part to the strong counter-arguments made by Whig M.P. William Windham, an opponent of Evangelical encroachments on traditional English sports and practices, who raised a host of practical difficulties in enforcing the law: if a horse on the road is abused, who is to be punished? The hired man who beat it? Its owner? The passenger on whose behalf the beating occurred? (See, in particular, Shivelow 202-205 on such questions.) These ambiguities circle around the question of the legal identification of the culpably cruel subject. If an act of cruelty occurs, how should it be attached to a punishable subject? This process of identification occurs far more easily in the public streets than elsewhere, and this fact and problem explains why cattle were the objects of these first attempts at legislation: cattle in this period were insistently visible in public space because used as transportation, which rendered cruelty against them more easily spotted. (The later nineteenth-century development of anti-cruelty legislation increasingly penetrated further into private or hidden spaces.)

Not without justice, William Windham pointed out some of the hypocrisies and class biases in a law that, in its focus on the crimes of drovers and carters on the streets to the exclusion of those of elites in their sports or homes, might, in his mocking words, have better been called “A Bill for harassing and oppressing certain classes among the lower orders of the people” (qtd. in Turner 123). Harriet Ritvo aptly identifies the “identification of cruelty as a lower-class propensity” (135) in much of the earlier nineteenth-century discourse around animal welfare. Indeed, the Chairman of the first meeting of the SPCA in 1824 troublingly offered as one of the organization’s primary aims “to spread amongst the lower orders of the people . . . a degree of moral feeling which would compel them to think and act like those of a superior class, . . . instead of sinking into a comparison . . . with the poor brute over which they exercised a brutal authority” (London Times 17 June 1824). There was some merit, then, in Windham’s earlier objections that the 1809 Act’s proposed definition of “cruelty” (and, implicitly, of “violence”) seemed to set a net designed to capture exclusively working-class perpetrators. Yet as Windham’s example also suggests, to point out the class biases of animal welfare proposals in this period could—given that regulation of elite sporting culture or scientific experimentation was off the table—also function simply as a shrewd rhetorical weapon on the side of those opposing any new regulation whatsoever.

Windham also broached a fascinatingly speculative philosophical objection: “Were everyone to feel with equal sensibility the pains of others as his own the world must become one unvaried scene of suffering, in which the woes of all would be accumulated upon each, and every man be charged with a weight of calamity beyond what his individual powers of endurance were calculated to support” (qtd. in Turner 122). Windham’s comments can be compared to George Eliot’s famous reflections in Middlemarch sixty or so years later: “If we had a keen vision and feeling of all ordinary human life, it would be like hearing the grass grow and the squirrel’s heart beat, and we should die of that roar which lies on the other side of silence” (ch. 20, n.pag.). “As it is,” she continues, “the quickest of us walk about well wadded with stupidity.” Windham seems to anticipate Eliot’s comments by arguing, in effect, that we must remain “well wadded,” with our sensibilities and ears protected from animal suffering, or else fear something like the madness that would accompany sensibilities enlarged to excess.

Lord Erskine’s well-publicized failures set the stage for the successes a little more than a decade later of an MP from Galway, ![]() Ireland: Richard Martin, later famous as “Humanity Dick” and dubbed “the Wilberforce of Hacks” by poet Thomas Hood (Shevelow 278)—a phrase that anticipates the famous description, later in the century, of Anna Sewall’s novel Black Beauty as “the Uncle Tom’s Cabin of the horse” (see Kean 79). In 1821 Martin proposed a “Bill to prevent the cruel and improper treatment of cattle” that passed Commons but failed to make it through the House of Lords. Finally, on 22 July 1822—with Lord Erskine’s support—what became known as Martin’s Law did make it through the Lords, received the Royal Assent, and became the world’s first animal-welfare legislation brought into law. The Parliamentary record sums up the Act: “Magistrates empowered to inflict a Penalty on Persons convicted of cruel Treatment of Cattle.” More elaborately, “Whereas it is expedient to prevent the cruel and improper Treatment of Horses, Mares, Geldings, Mules, Asses, Cows, Heifers, Steers, Oxen, Sheep and other Cattle. . . . That if any Person or Persons shall wantonly and cruelly beat, abuse, or ill treat any Horse, Mare, . . . [etc.], and Complaint on Oath thereof be made to any Justice of the Peace or other Magistrate within whose Jurisdiction such Offence shall be committed,” then “he, she or they so convicted shall forfeit and pay any Sum not exceeding Five Pounds, nor less than Ten Shillings” (Statutes of the United Kingdom 403).

Ireland: Richard Martin, later famous as “Humanity Dick” and dubbed “the Wilberforce of Hacks” by poet Thomas Hood (Shevelow 278)—a phrase that anticipates the famous description, later in the century, of Anna Sewall’s novel Black Beauty as “the Uncle Tom’s Cabin of the horse” (see Kean 79). In 1821 Martin proposed a “Bill to prevent the cruel and improper treatment of cattle” that passed Commons but failed to make it through the House of Lords. Finally, on 22 July 1822—with Lord Erskine’s support—what became known as Martin’s Law did make it through the Lords, received the Royal Assent, and became the world’s first animal-welfare legislation brought into law. The Parliamentary record sums up the Act: “Magistrates empowered to inflict a Penalty on Persons convicted of cruel Treatment of Cattle.” More elaborately, “Whereas it is expedient to prevent the cruel and improper Treatment of Horses, Mares, Geldings, Mules, Asses, Cows, Heifers, Steers, Oxen, Sheep and other Cattle. . . . That if any Person or Persons shall wantonly and cruelly beat, abuse, or ill treat any Horse, Mare, . . . [etc.], and Complaint on Oath thereof be made to any Justice of the Peace or other Magistrate within whose Jurisdiction such Offence shall be committed,” then “he, she or they so convicted shall forfeit and pay any Sum not exceeding Five Pounds, nor less than Ten Shillings” (Statutes of the United Kingdom 403).

As Hilda Kean notes, with this statute, the “state was intervening in ‘domestic relationships’ decades before it would do so on behalf of children or adult women” (34). Antony Brown observes that “Englishmen really did feel that it was important for a man to be able to beat his own horse if it was his own property—it was one of the bastions of his liberty” (12). Those defenders of tradition who had fought for the continued right of human subjects to treat animals as no more than property had probably been correct to resist Martin’s Bill, at least insofar as it proved an important precedent for later diminishing of the sovereign power of the elite male subject to treat his dependents as he wished within the private space of the home (as with the 1884 founding of the London Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Children—on which see Flegel).

For Martin’s Bill to become law, however, it had to pass through what was in effect a final crucible of laughter and ridicule, one that reminds us that the cultural role of “defender of animals” had become widely associated, at this period, with possibly-insane preachers, over-sensitive Evangelicals, and poets. “In the Commons,” one historian reports, “Martin’s bill was greeted with the usual storm of laughter, ridicule, and outraged hostility, as its opponents rose to denounce it. Their arguments had not changed since a decade before;” the “animated debate [was] infused with ridicule, scoffing, and general hilarity (Shevelow 247, 249). The Times report of the initial, failed 1821 attempt by Martin to present the bill suggests an atmosphere of schoolboy hilarity in the Commons:

Mr. Alderman C. Smith . . . thought that asses should also be protected from the cruelty to which they were so often exposed. (Laughter.) The hon. Alderman went on to show the humanity and the necessity of affording protection to asses; but we could not catch the particulars of his remarks, owing to the noise and laughter which prevailed. He continued by moving an amendment that, after the word “horses” the word “asses” should be inserted. (Loud laughter followed this amendment, which was considerably increased when it was put by the chairman) (London Times 2 June 1821).

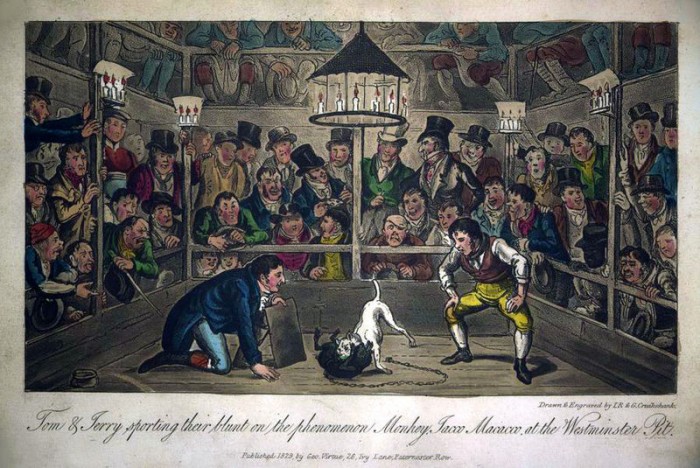

The Times report on Martin’s speech in the House of Commons of 16 May 1822 further dramatizes the rhetorical battle in which Martin engaged in order to defuse or deflect the ridicule and amusement of some of his peers. Martin is describing in Parliament, as an example of the kind of public abuse of animals one can encounter in London, a sort of “Battle Royale” he had recently encountered between the celebrated (and variously-spelled) monkey gladiator Jacco Macacco and a dog. Martin here reads from a bill advertising the show:

One of the printed bills ran as follows:— “Jacco Maccacco, the celebrated monkey, will this day fight Tom Crib’s white bitch Puss. (A laugh.) Jacco has fought many battles with some of the first dogs of the day, and has beat them all, and he hereby offers to fight any dog in England of double his own weight.” (A laugh.) The battle administered in this bill took place, and after having concluded for upwards of half an hour, it terminated by Puss tearing away the whole of the under jaw of Jacco, who, on his part, lacerated the windpipe and the arteria carotis of Puss. (A laugh.) In this state the animals lived for two hours, and then they died. (A laugh.) He would be the last man living to interfere with what might properly be called the amusements of the people, but scenes such as he had described could afford pleasure only to the lowest and the vilest of mankind. (Hear.) (London Times May 17 1822)

Figure 1: Engraving by George Cruikshank, Tom and Jerry sporting their Blunt on the phenomenon monkey Jacco Macacco at the Westminster-Pit, c. 1820

The Times’ transcript is disconcerting to read, offering vivid evidence of the historical transformation of social or behavioral norms. How could a collection of law-makers react to the story of a monkey and a dog’s gruesome battle to maiming and death, performed as a public entertainment, with hearty laughter? The pattern of the journalist’s interpolations can be read as an encapsulation of what Richard Martin achieved: “A laugh,” “A laugh,” “A laugh,” “A laugh,” and then, finally, “Hear,” as one listener supported Martin. One colleague observed that Martin’s bill, “ridiculed as it had been, had already conferred great benefit upon the community” (London Times 10 March 1824)). That Martin’s Act was easily “ridiculed” or turned into a jest was, arguably, intrinsic to its identity and even to its eventual success, as we shall see.

“How was it,” two RSPCA officials ask in a 1924 history of the association, “that Richard Martin succeeded where Lord Erskine and his predecessors had failed?” (Fairholme and Pain 27) The authors cite a contemporary newspaper of the 1820s that asserted, “Mr. Martin is not a very learned man, neither is he, in the language of the schools, eloquent, but he has a most winning way about him. He holds the House by the very test of the human race, laughter, and while their sides shake, their opposition is shaken and falls down at the same instant” (qtd. 27). Kathryn Shivelow writes that many of Martin’s colleagues “tended to view Martin as a jokester, even a buffoon—an impression he seemed to encourage. He often acted the wag, . . . making speeches so witty that his colleagues were convulsed in laughter” (254).

Shortly after the ratification of the Act, a popular comic song was published in London offering a tribute to Richard Martin. If to ridicule is to “turn into a jest” or joke, this song was, perhaps, the literal jest attached to the “ridiculed” Martin’s Act. Based on the actual trial of a costermonger who was the first person prosecuted under the Act, it tells the tale of two donkey owners, a kind one (narrating the tale) and a cruel one, Bill, who beats his animal.

Wot makes me mention this this morn,

I seed that cruel chap, Bill Burn—

Whilst he was out a-crying his greens—

His donkey wollop with all his means.

He hit him o’er his head and thighs,

He brought the tears up in my eyes…

Bill’s donkey was ordered into court,

In which he caused a deal of sport;

He cock’d his ears, and ope’d his jaws,

As if he wished to plead his cause.

I prov’d I’d been uncommonly kind,

The ass got a verdict—Bill got fined;

For his worship and I were of one mind,

And he said:

If I had a donkey wot wouldn’t go,

D’ye think I’d wollop him? No, no, no!

But gentle means I’d try, d’ye see,

Because I hate all cruelty.

If all had been like me, in fact,

There ha’ been no occasion for Martin’s Act —

Dumb animals to prevent getting crackt

On the head. (qtd. in Fairholme and Pain 33-4; also see Brown 18-19)

The song suggests that “if all had been like me,” the Act would have been unnecessary. But it also seems slyly to allegorize the passing of Martin’s Act itself, with the donkey standing in court “as if he wished to plead his cause” a figure reminiscent of the “asses” on whose behalf Alderman Smith was so exercised: “the ass got a verdict” after all.

Figure 2: Painting of the Trial of Bill Burns. Note that the text of Martin’s Act lies in the left foreground. On this painting, see Shivelow 263-4

Whether more due to Martin’s own personal qualities and legislative skills, or to the slow shift in public consciousness having simply reached a tipping point, Martin had achieved something monumental, a national legislation testifying (if only to a point and provisionally) the legal personhood of certain nonhuman creatures, their standing as legal subjects possessing rights and protections beyond those due to them as possessions. He did so in part, it would seem, by facing up to and rerouting the quality of ludicrousness, humor, and disbelieving laughter that had always accompanied any efforts to change the standing of animals. The comic song about the two donkey-owners stands as an apt tribute to Martin’s legislative accomplishment, and even perhaps as a necessary ratification of it, in the way it in effect redirects and redefines the mocking laughter that would greet an animal in the courtroom. The song now seems to accept an animal’s presence within the space of the law as a given: a cause for humor, yes, but not for “disgust” or a sense of the “prostitution of the dignity” of the court (to draw on language from James Granger’s postscript to his unpopular 1772 sermon).

On 16 June 1824, as the Times reported the next day, “the friends of the bill for the prevention of cruelty to animals assembled . . . at Old Slaughter’s Coffee-house, in St. Martin’s-lane, for the purpose of forming a Society more effectively to check the practice of treating the brute creation with cruelty.” Thus was the Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals formed, England’s and indeed the world’s first society of the kind. (A Society for Preventing Wanton Cruelty to Brute Animals was founded in ![]() Liverpool in 1810 but apparently never got much past its founding.) The organization—which became the Royal Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals in 1840, with Queen Victoria’s dispensation—was led by Arthur Broome, an

Liverpool in 1810 but apparently never got much past its founding.) The organization—which became the Royal Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals in 1840, with Queen Victoria’s dispensation—was led by Arthur Broome, an ![]() Oxford graduate and pastor in

Oxford graduate and pastor in ![]() Middlesex who subsequently retired to focus on the organization. Among the twenty-one other men who showed up at the meeting were Richard Martin (of course), the abolitionist William Wilberforce, and several other Members of Parliament, clergymen, journalists, and barristers. (See, e.g., Shevelow 268-269; Fairholme and Pain 51-58).

Middlesex who subsequently retired to focus on the organization. Among the twenty-one other men who showed up at the meeting were Richard Martin (of course), the abolitionist William Wilberforce, and several other Members of Parliament, clergymen, journalists, and barristers. (See, e.g., Shevelow 268-269; Fairholme and Pain 51-58).

These struggles and events of the early 1820s moved the causes of animal rights, animal welfare, and anti-cruelty to something close to the mainstream of British society. By contemporary standards, legal protections for animals were still minimal, often toothless, and highly selective in how, where, and to which species they were applied. The SPCA struggled for years with the problem of enforcement and whether paid “inspectors,” hired to find and report violations of the law, were a necessary evil. Treatment of animals remained a “private” matter in the minds of many English citizens, and the regulation of this treatment therefore a flashpoint for debates about state interference. But animals had, crucially—like the donkey in the song—entered the courtroom in a way that would allow subsequent developments and extensions of the law, and of public opinion, throughout the century. (See also other BRANCH entries by Teresa Mangum, Mario Ortiz-Robles, and Susan Hamilton, all forthcoming.)

HOW TO CITE THIS BRANCH ENTRY (MLA format)

published April 2012

Kreilkamp, Ivan. “The Ass Got a Verdict: Martin’s Act and the Founding of the Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals, 1822.” BRANCH: Britain, Representation and Nineteenth-Century History. Ed. Dino Franco Felluga. Extension of Romanticism and Victorianism on the Net. Web. [Here, add your last date of access to BRANCH].

WORKS CITED

Bentham, Jeremy. An Introduction to the Principles of Morals and Legislation. 1781. Ch. 17. Library of Economics and Liberty. Web. 30 Oct. 2011.

Blake William. “Auguries of Innocence.” English Poetry. Indiana U Library. Web. 8 Oct. 2011. <http:collections.chadwyck.co.uk>

Brown, Antony. Who Cares for Animals: 150 Years of the RSPCA. London: Heinemann, 1974. Print.

Cowper, William. “The Task.” Chadwyck-Healey collection, English Poetry. Indiana U Library. Web. 8 Oct. 2011. <http:collections.chadwyck.co.uk>

Eliot, George. Middlemarch. 1871. Project Gutenberg. Web. 8 Oct. 2011.

Fairholme, Edward G. and Wellesley Pain. A Century of Work for Animals; the History of the R.S.P.C.A., 1824-1924. New York: E.P. Dutton, 1924. Print.

Flegel, Monica. Conceptualizing Cruelty to Children in Nineteenth-Century England: Literature, Representation, and the NSPCC. Aldershot: Ashgate, 2009. Print.

Granger, James. An Apology for the Brute Creation; or Abuse of Animals Censured. T. Davies, 1776. Eighteenth Century Collections Online (ECCO). Web. 12 Oct. 2011.

Kean, Hilda. Animal Rights : Political and Social Change in Britain since 1800. London: Reaktion Books, 1998. Print.

Lawrence, John. A philosophical and practical treatise on horses, and on the moral duties of man towards the brute creation. London, [1796]-98. Eighteenth Century Collections Online (ECCO). Web. 12 Oct. 2011.

London Times May 16 1809. The Times Digital Archive, 1785–2006. Web. 12 Oct. 2011.

London Times May 17, 1822. The Times Digital Archive, 1785–2006. Web. 12 Oct. 2011.

London Times June 2 1821. The Times Digital Archive, 1785–2006. Web. 12 Oct. 2011.

London Times June 17 1824. The Times Digital Archive, 1785–2006. Web. 12 Oct. 2011.

London Times March 10 1824. The Times Digital Archive, 1785–2006. Web. 12 Oct. 2011.

Oswald, John. The Cry of Nature; An Appeal to Mercy and to Justice on Behalf of the Persecuted Animals. 1791. Lewiston: Edwin Mellen, 2000. Print.

Primatt, Humphrey. The Duty of Mercy and the Sin of Cruelty. 1776. Lewiston: Edwin Mellen, 1997. Print.

Ritvo, Harriet. The Animal Estate: The English and Other Creatures in the Victorian Age. Cambridge: Harvard UP, 1989. Print.

Shevelow, Kathryn. For the Love of Animals: The Rise of the Animal Protection Movement. New York: Henry Holt & Co., 2008. Print.

The statutes of the Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland, 3 George IV, 1822. His Majesty’s statute and law printers, 1822. Google Book Search. 403. Web. Oct 24, 2011.

Thomas, Keith. Man and the Natural World. London: Allen Lane, 1983. Print.

Turner, E.S. All Heaven in a Rage. New York: St. Martin’s Press, 1965. Print.

Young, Thomas. An Essay on Humanity to Animals. 1798. Lewiston: Edwin Mellen, 2001. Print.

RELATED BRANCH ARTICLES

Philip Howell, “June 1859/December 1860: The Dog Show and the Dogs’ Home”

Susan Hamilton, “On the Cruelty to Animals Act, 15 August 1876″

Mario Ortiz-Robles, “Animal Acts: 1822, 1835, 1849, 1850, 1854, 1876, 1900″