Abstract

This essay explores the underlying developments which provoked the romantic novelist Ouida to launch a virulent attack in the correspondence columns of The Times on the syndication of fiction – that is, its broadcast distribution in newspapers – as the most alarming symptom of the commercialization of literature in the late nineteenth century.

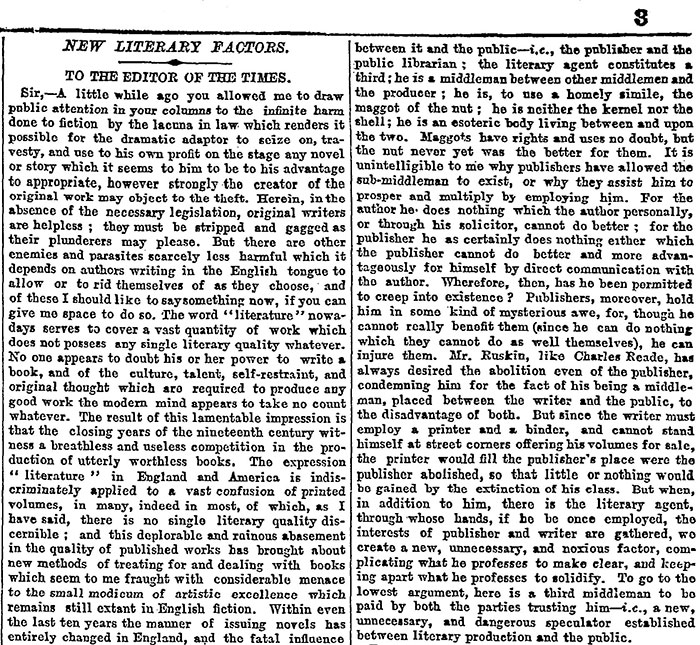

The syndication of fiction – that is, the broadcast distribution of fiction material in newspapers and other periodicals, a mode of serialization originating in the English-speaking world around the middle of the nineteenth century – received very bad press. Perhaps the most damning report came from the British romantic novelist “Ouida,” in a letter dated 20 May (Fig. 1) and addressed to the editor of The Times, which appeared under the heading “New Literary Factors” on 22 May 1891:

Within even the last ten years the manner of issuing novels has entirely changed in England, and the fatal influence of America is as disastrous to English writers as to English farmers. Owing to American demands and examples, the author has no longer to deal with a single publisher whose interests were identical with his own, and who often possessed some regard for the dignity and delicacy of art, but has to suffer from and arrange with “syndicates” which deal wholesale in fiction as other “syndicates” deal with bubble companies, building speculations, and the shares of railways running, with profit only to the promoters, from No Man’s Land to Nowhere. I have before me the advertisements, English and American, of what is termed a “Fiction Bureau” and an “Associated Literary Press,” amalgamated companies which buy and run an author as a speculator on the Turf buys and runs a colt. These syndicates have been in existence for some years, and deal in literature (or in what passes under the generic name of literature) as other speculators deal in raw hides, wholesale teas, or preserved meats. They have. . . an “immense organization” which treats authors precisely as the

Chicago killing and salting establishments treat the pig; the author, like the pigs, is purchased, shot through a tube, and delivered in the shape of a wet sheet (as the pig is in the shape of a ham), north, south, east, and west, wherever there is a demand for him.

For all the extravagance of the rhetoric, which failed to elicit support from other correspondents despite filling almost two columns, and the indiscriminate character of her attack – literary agencies and writers’ associations were also targeted, provoking Walter Besant of the Society of Authors to a brisk retort dismissing her accusations as “sham indignation and froth” (Besant) – Ouida’s condemnation of the syndicates often seems to have been taken as justified. To examine its validity, this article aims to provide a detailed analysis of the development of fiction syndication in the second half of the nineteenth century by focusing in turn on the syndicating agents, the material syndicated, the print media employed, the audiences reached, and, finally, the impact on literary authorship and literary form.

Fiction Syndicators

According to the Oxford English Dictionary, the noun “syndicate” only acquired an economic significance during the railway boom of the second half of the nineteenth century, when it began to be used to refer to “a combination of. . . financiers entered into for the purpose of prosecuting a scheme requiring large resources of capital, esp. one having the object of obtaining control of the market in a particular commodity.” By the last quarter of the century, however, the verb form was being employed specifically in the sense of “to publish simultaneously in a number of periodicals.” This transference of meaning is misleading in a number of ways, since by then the widespread business of selling on editorial material to a range of newspapers was most typically conducted by under-capitalized organizations that faced stiff competition and were located a long way from the main centers of finance. Contemporary English commentators assumed that the practice must have been imported from America, and pioneering scholars in the field worked on this assumption (Watson; Pollard), but more recent studies suggest rather that it was born and bred in the British provinces and colonies (Johanningsemeier; Law, Serializing), only a couple of decades after the emergence in ![]() France of the roman feuilleton or newspaper novel (Queffélec).

France of the roman feuilleton or newspaper novel (Queffélec).

During the heyday of the fiction syndicates in the 1880s, the dominant organizations tended to be either branches of firms publishing newspapers and other periodicals, or independent bureaus offering fiction syndication alongside other literary services. However, the earliest experiments in newspaper syndication seem to have been carried out by the authors themselves, in particular enterprising provincial novelists with local themes whose access to the publishing mechanisms of the metropolitan market was limited at best. The Scottish lowlands offered especially fertile territory for popular journalism at the mid-century (Donaldson), and it was there that the literary potential of the newspaper serial was explored by a large number of writers, most notably David Pae (1828-84). In a journalistic career of some thirty years, Pae wrote at least fifty lengthy melodramatic novels with evangelical themes, and thereby became one of the most widely read novelists in the country, despite the fact that few of them ever appeared in book form. Beginning with Lucy, the Factory Girl in 1858, Pae began to persuade newspaper editors in both ![]() Edinburgh and

Edinburgh and ![]() Glasgow to share his latest offerings; by 1870, at least the author was broadcasting printed publicity and each of his new novels was being serialized in around a dozen major weeklies all over

Glasgow to share his latest offerings; by 1870, at least the author was broadcasting printed publicity and each of his new novels was being serialized in around a dozen major weeklies all over ![]() Scotland,

Scotland, ![]() Ulster, and northern England. A number of British authors followed Pae’s example as a self-syndicator, though none enjoyed the same sustained success. In the 1870s, Captain Mayne Reid (1818-83), best known for his juvenile tales of the American Wild West, was among the more memorable names to take this approach, while in the 1880s lesser-known novelists like the Cornishman James Skipp Borlase (b. 1839) were advertising their wares to all-comers in the columns of trade organs like The Journalist. Borlase in fact seems to have started to syndicate his stories in

Ulster, and northern England. A number of British authors followed Pae’s example as a self-syndicator, though none enjoyed the same sustained success. In the 1870s, Captain Mayne Reid (1818-83), best known for his juvenile tales of the American Wild West, was among the more memorable names to take this approach, while in the 1880s lesser-known novelists like the Cornishman James Skipp Borlase (b. 1839) were advertising their wares to all-comers in the columns of trade organs like The Journalist. Borlase in fact seems to have started to syndicate his stories in ![]() New South Wales back in the 1860s, when Australian colonial newspapers were also crying out for steady supplies of entertaining fiction (Law, “Savouring” 194).

New South Wales back in the 1860s, when Australian colonial newspapers were also crying out for steady supplies of entertaining fiction (Law, “Savouring” 194).

Fig. 2: Publicity material from the self-syndicator David Pae of ![]() Newport-on-Tay,

Newport-on-Tay, ![]() Fifeshire (c.1870); Fig. 3: Publicity material from the syndicators Tillotson & Son of Bolton, Lancashire (c. 1884)

Fifeshire (c.1870); Fig. 3: Publicity material from the syndicators Tillotson & Son of Bolton, Lancashire (c. 1884)

But by the late 1870s at least, a more common route for the novelist seeking a wide newspaper readership was to sell serial rights to one of the many organizations specializing in syndication. For the enterprising newspaper company anxious to secure a steady supply of quality material, a good option was to share the costs with like-minded journals, and thus develop into a syndicating office. Among the longest-running British syndicators in this category were: “Cassell’s General Press” (from 1862), a division of the most successful popular serial publishers in London, founded by John Cassell; Leader & Sons of the Sheffield Independent, who in 1873 took over the business founded a decade earlier by Samuel Harrison of the Sheffield Times; Tillotson & Son, proprietors of a chain of “Lancashire Journals” centered in ![]() Bolton, whose “Fiction Bureau” operated from 1873 until 1935; and W.C. Leng & Co. of the Sheffield Telegraph, whose “Editor’s Syndicate” flourished for a decade from around 1885. The most important independent British syndicators evolved from or into general advertising, press and literary agents, tending to be based in London and with only indirect access to printing facilities. They included: the National Press Agency, founded in 1873 with links to the Liberal Association, which was still in operation at the turn of the century; A.P. Watt’s “Literary Agency” (from c. 1878), the first successful example, which was especially active in fiction syndication in the 1880s; the “Authors’ Syndicate” (1890), under the auspices of the Society of Authors with W. M. Colles as secretary; and the Quaker-run “Northern Newspaper Syndicate” in

Bolton, whose “Fiction Bureau” operated from 1873 until 1935; and W.C. Leng & Co. of the Sheffield Telegraph, whose “Editor’s Syndicate” flourished for a decade from around 1885. The most important independent British syndicators evolved from or into general advertising, press and literary agents, tending to be based in London and with only indirect access to printing facilities. They included: the National Press Agency, founded in 1873 with links to the Liberal Association, which was still in operation at the turn of the century; A.P. Watt’s “Literary Agency” (from c. 1878), the first successful example, which was especially active in fiction syndication in the 1880s; the “Authors’ Syndicate” (1890), under the auspices of the Society of Authors with W. M. Colles as secretary; and the Quaker-run “Northern Newspaper Syndicate” in ![]() Kendal, north Lancashire, a major rival to Tillotson’s, founded in 1891 and surviving for around thirty years. Thus, as perhaps her personal experience as a client author of both the Tillotson and Leng syndicates during the 1880s might have warned her (Law, Serializing 85, 148), Ouida was quite mistaken in her diagnosis of the wholesale distribution of fiction as a literary disease spreading to England from across the Atlantic.

Kendal, north Lancashire, a major rival to Tillotson’s, founded in 1891 and surviving for around thirty years. Thus, as perhaps her personal experience as a client author of both the Tillotson and Leng syndicates during the 1880s might have warned her (Law, Serializing 85, 148), Ouida was quite mistaken in her diagnosis of the wholesale distribution of fiction as a literary disease spreading to England from across the Atlantic.

Yet, though the U.S. syndicators started up later and initially imitated technical and literary innovations in the British market, by the last decades of the century they were operating in rather greater numbers and on a much larger scale. Then American operators could expect to sell the same story to over a hundred different newspapers, while those in Britain might be satisfied with a dozen or less. Among the more powerful syndicates operated by newspaper editors were those of: Charles A. Dana at the ![]() New York Sun (from around 1884); Charles Taylor of the Boston Globe (again 1884); and Victor Lawson at the Chicago Daily News (c. 1896). The most memorable independent syndicating agencies were probably those run by: the A.N. Kellogg Newspaper Company based in Chicago (from 1865); the American Press Association (from 1882, also in Chicago), Irving Bacheller’s Newspaper Syndicate in New York (from c. 1884); and S.S. McClure’s Associated Literary Press (again c. 1884 in New York) (Johanningsmeier; Lyon). Rivalry among these competing syndicators was typically intense, but there were also examples of short- or long-term alliances: by the 1880s many of the leading syndicators in both the

New York Sun (from around 1884); Charles Taylor of the Boston Globe (again 1884); and Victor Lawson at the Chicago Daily News (c. 1896). The most memorable independent syndicating agencies were probably those run by: the A.N. Kellogg Newspaper Company based in Chicago (from 1865); the American Press Association (from 1882, also in Chicago), Irving Bacheller’s Newspaper Syndicate in New York (from c. 1884); and S.S. McClure’s Associated Literary Press (again c. 1884 in New York) (Johanningsmeier; Lyon). Rivalry among these competing syndicators was typically intense, but there were also examples of short- or long-term alliances: by the 1880s many of the leading syndicators in both the ![]() United States and Britain had international clients, so that there were occasionally tie-ups across the Atlantic, such as those between Tillotson in Bolton and McClure in New York in the late 1880s, or Leng in Sheffield and Lawson in Chicago from the early 1890s.

United States and Britain had international clients, so that there were occasionally tie-ups across the Atlantic, such as those between Tillotson in Bolton and McClure in New York in the late 1880s, or Leng in Sheffield and Lawson in Chicago from the early 1890s.

Syndicated Fiction

With the occasional exception (notably Leng’s Editor’s Syndicate), the press copy distributed by the organizations detailed above was by no means limited to narrative fiction: news stories both national and international, social and political commentaries, regular and special features, plus entertainment material including puzzles and cartoons, were all offered by the nineteenth-century syndicators, as they still often are today. Despite the name, Tillotson’s Fiction Bureau quickly began to provide a weekly “London Letter” and “Ladies Column,” among other regular features; A. P. Watt began business as an advertising agent distributing display copy to the journals that later offered venues for the literary works of his client authors; for not only the American Press Association but also the National Press Association in Britain, the core business was in news and opinion, with literary material only an ancillary service; something similar was true of both Cassell’s in London and Kellogg’s in Chicago, who, in the early stages at least, provided a general newspaper syndication service that gave client newspapers little freedom to pick and choose.

But printed serial fiction was as universally popular in the second half of the nineteenth century as televised serial drama was to be in the second half of the twentieth, so that few syndicators could hold back from entering the market and most advertised their fiction offerings prominently. These included not only novels in installments but also “complete tales,” as short stories were often referred to in the nineteenth-century press. Virtually throughout the Victorian period, complete tales were particularly associated with the Christmas season, when special issues packed with entertaining material were a common feature of popular periodicals, and similar supplements soon began to appear at the summer holiday season. Many local newspapers began their fiction offerings with such holiday fare, gradually expanded their publication of longer tales, and eventually graduated to full-length serial novels, using short stories then only to bridge the occasional gap. Early on, local self-syndicating authors seemed free to write at virtually any length; the thirty or so serials itemized in David Pae’s backlist of c. 1870 average around thirty-six single-chapter installments, but varied from a high of ninety-six to a low of eleven. Later, when metropolitan authors began to find newspaper syndication an attractive alternative to magazine serialization, length was more strictly determined by the demands of the book market where their serial novels would eventually appear; in Britain, the three-decker format dictated by the circulating libraries had encouraged serial novels of around thirty installments into the 1890s, whereas American authors had been free much earlier to explore a more compact format of around half that length. By the final decade of the century, though, as an alternative to the serial novel, the syndicators had begun to offer complete tales in series by a single author or a group; Tillotson’s, for example, then distinguished between “short stories” of around five thousand words and “storyettes” of half that length, both typically offered in quarterly or half-yearly sets (Turner). In sum, though the demands of their client publishers tended to make the syndicators stricter regarding installment lengths and deadlines than the editors of metropolitan magazines, the client authors were still offered a good deal of freedom regarding both form and content, so that the system was far from the relentless factory conveyor belt depicted by Ouida.

Syndicated fiction included both original and reprinted material, perhaps in roughly equal measure. In the early days, the absence (until 1891) of any international copyright agreement between the United States and the rest of the world, not excluding the United Kingdom, meant that both British and American editors were free to “borrow” literary material previously published in periodicals on the other side of the Atlantic as soon as the post arrived, while U.S. journals seem to have cooperated in a policy of “exchange” among themselves that was merely systematized by the pioneer syndicators. Self-syndicators like Pae and Reid tended to distribute their wares to the newspapers in series rather than in parallel, so that most appearances were technically reprints, while early newspaper syndicators like Tillotson and Leader at first were able to purchase unlimited serial rights from authors and thus maintain a substantial backlist of old material. When the power of the fiction brokers began to decline at the turn of the new century, they were frequently reduced to selling cheaply material that had already been published widely in book form. But at their zenith, the syndicates were regularly in a position to acquire the latest work by novelists with established literary reputations and in the face of competition from prestigious literary magazines.

A wide variety of narrative forms was also represented among syndicated fiction. It is true that issuing novels in frequent installments tends to stimulate a psychological dependence on mystery and suspense, so that the staple genres of nineteenth-century newspaper fiction can be said to be, in turn, the gothic melodrama, the sensation novel, the adventure romance, and the detective story. But the pull of realism was throughout a powerful force, so that the search for “local color” was as significant for early Scottish newspapers novelists like David Pae as it was for American naturalists like Stephen Crane, who found a ready market with the syndicates near the end of the century. Thus, British novelists who enjoyed regular success in the newspaper press included not only sensationalists like Mary Braddon and Wilkie Collins, but also realists like Anthony Trollope, Thomas Hardy, and Rudyard Kipling; at the same time, the American syndicates seem to have fought over the stories of Mark Twain, William Dean Howells, and Henry James just as much as over the formula fiction of “Bertha M. Clay” or Anna Katherine Greene. The reality was thus far from matching Ouida’s assertion which, relying on the analogy of the Chicago meat packers, suggested that the syndicators insisted on a uniform product of low quality that could be distributed indiscriminately to all outlets.

Syndication Media

A general rule applying to literary syndication is that the various journals receiving the material in question should have discrete circulations; otherwise, in the words of the editor of the Glasgow Weekly Herald, the practice is “apt to give readers the impression that they are being asked to pay for matter which is cheap common property” (Sinclair 184). This means that, in principle, the journals subscribing to syndicated material should not have a nationwide circulation but be limited to a specific geographical area. While this restriction does not altogether exclude other kinds of periodical, such as literary or general magazines, it does mean that local and regional newspapers are likely to be the principle clients of the syndicates. The second half of the nineteenth century witnessed an extraordinary boom in newspaper production and readership, one that considerably outstripped the growth in the book industry and was especially marked in provincial areas. Between 1860 and 1899, the number of periodical titles issued in Britain and America increased respectively by around 325% and 450% to 4,654 and 18,793, with daily papers then in each case accounting for little more than 10% of the total (Eliot 148; Dill 28). In the final decades of the century, though, the growth in magazine production was even more rapid, especially in Britain where the number of newspaper titles peaked as early as 1900 and was overtaken by the number of magazine titles two years later. These statistics help to explain the general rhythm of the rapid rise and slow decline of fiction syndication.

In practice, the syndication rules stated above were much easier to maintain in the United States, where the vastness of the national territory then severely constrained the possibilities of nationwide distribution of serial publications published at less than monthly intervals. In Britain, things were rather more tricky to manage. By the second half of the nineteenth century, a significant number of journals published in the metropolis, both weekly and daily, were being distributed all over the British Isles; moreover, regional journals issued in major cities like Manchester and Liverpool, or Glasgow and Edinburgh, often had significant overlaps in circulation in the rural hinterland between. Thus, in the early 1880s, when A. P. Watt tried to increase the profit from the serialization of the latest novel of his new client Wilkie Collins, by creating a tightly packed syndicate that also included a metropolitan paper, there were loud cries of foul from all sides (Law, Serializing 102-5). This is one reason why fiction syndication in the United Kingdom took place overwhelmingly in weekly journals, while in the United States serialization in daily installments was also very common. It is also perhaps a reason why the British operators were quicker to explore overseas markets than their American counterparts.

Tillotson’s Fiction Bureau, the pioneers in this department, began actively to acquire Australian and other colonial serial rights in the late 1870s and those for the US from the early 1880s, opening a Berlin office to expand its continental European sales before the end of the decade. In Europe, the policy seems to have been to sell rights to a single national journal in each major language area, but in both Australasia and North America local agents were typically employed to generate syndicates of local subscribing newspapers in the same way as in the domestic market. Other syndicators with a particular focus on literary material were to follow suit sooner rather than later, notably Watt’s Literary Agency, Leng’s Editor’s Syndicate, and the Northern Newspaper Syndicate in Britain, and the organizations headed by Bacheller, McClure, and Lawson in America. Apart from the transatlantic trade in serial fiction, the most important external market for each of these fiction brokers was clearly the Australian colonies where the newspaper press also flourished greatly in the later Victorian decades (Johnson-Woods; Law, “Savouring”).

The various physical media via which literary material was distributed by the syndicators are also worthy of note, in that their qualities mirror the distinctive characters and requirements of the receiving journals. In the earliest days, self-syndicators like Pae seem to have distributed their wares to potential and actual client newspapers in manuscript form, though it remains uncertain whether the labour of duplication was typically performed by professional copyists or the writers themselves. But by the early 1860s at least, two methods of mechanical reproduction of editorial material were available to the syndicates, both suitable for transportation by rail: partly-printed sheets (also known as patent insides or readyprint) and stereotype plates (often abbreviated to stereo or plate). In the case of readyprint service, single sheets to be folded to form four-page newspapers would be printed on the inside only with general information, entertainment, and advertising material by the syndicating office, before being forwarded to a range of local newspaper firms where local news and advertising would be added on the outside, often in a different layout and/or typeface; halfsheets could also be printed in advance on both sides to serve as inserts or supplements. This type of service was particularly suitable for papers just starting up or those serving small towns or scattered rural communities. Cassell’s General Press in London and the Kellogg Newspaper Company in Chicago long specialized in this branch of the business, and soon began to include short and serial tales among their pre-printed matter. In the case of plate service, metal plates were cast from papier-maché molds taken from the surface of columns of type representing a wide range of editorial material, including fiction; to reduce the costs of transportation and storage space, the stereotype plates were made of lightweight materials such as aluminum or later cellulose, and as thinly as possible, being brought up to type height by being locked onto reusable blocks kept at the printing department of the receiving newspaper. This service, standard for press agencies like the American in Chicago and the National in London, appealed especially to larger urban journals wishing to add variety to their editorial offerings, but preferring to exercise more control over both content and form than those receiving pre-printed matter. Both readyprint and plate service allowed easy replication of visual material, whether pictorial puzzles or story illustrations, and were sometimes offered as alternatives by the same syndicating organization.

Regional newspapers with the widest circulations and most prestigious reputations, however, typically preferred to receive syndicated copy in the form of printed paper slips (often referred to as galley proofs or reprint), which were available from the mid-1860s at least. This medium allowed absolute control over format and also offered leeway for editorial interference, such as the cutting of material deemed tedious or offensive. The heavier costs of sea transportation meant that newspapers or agents overseas were invariably supplied with syndicated copy in reprint rather than in stereo or readyprint, though the galley proof slips were normally sent in duplicate to reduce the risk of delays and accidents on the ocean. In general, prices charged by the syndicator varied not only with the length of the fiction material and the medium via which it was distributed, but also according to the status of the author and the sales of the receiving journal. Thus, as the decidedly provisional and piecemeal nature of these various arrangements suggests, for all Ouida’s protests, in reality there was almost nothing in common between large-scale financial combinations like the railway syndicates and the operations of fiction agencies such as Tillotson’s or Bacheller’s.

Syndicate Audiences

The attraction of the newspaper syndicates to established novelists was precisely that they could reach not only a considerably larger but also a more diversified readership than any single literary magazine, and thus offer significantly higher sums for serial rights. It was thus by no means the case that, as Ouida claimed, the economic gains went “only to the promoters.” Already before the end of the nineteenth century, the total number of newspaper subscriptions in the United States alone has been estimated at well over one hundred million (Dill 11-12). However, before the turn of the twentieth century when advertisers began to insist on audited evidence, it is often difficult to obtain reliable figures concerning the sales of even major newspapers, and thus problematic to calculate the precise number of copies sold of any given syndicated novel. Many of the small local papers serviced by Cassell’s or Kellogg’s pre-printed sheets in the early 1860s may have had a circulation of only a thousand or so, but with dozens of such clients it was not difficult to reach 50,000 subscribers for anonymous and often reprinted tales. At the same time, there is solid evidence to support the following minimum domestic sales figures for representative syndicates of major city or regional newspapers: 150,000 for Lucy, the Factory Girl and other novels by David Pae by the late 1860s; a quarter of a million in the case of Tillotson’s first major “coterie” in 1873, for Mary Braddon’s Taken at the Flood; half a million for A.P. Watt’s distribution of I Say No and other novels by Wilkie Collins in the mid-1880s; and a million for the most effective of the syndicates of McClure and Bacheller in the early 1890s, such as Mark Twain’s The American Claimant or Stephen Crane’s The Red Badge of Courage (Law, Serializing 127-34; Johanningsmeier 203-5). These are figures that no single contemporary literary periodical could come close to matching. However, it has sometimes been suggested that newspapers were by then already ephemeral and disposable media, that syndicated literary matter in particular functioned mainly as filler, and thus that few of these many tens of thousands of subscribers may have actually read the novels in question. But this does not make economic sense: for why then should Tillotson or McLure have fought to recruit authors of the standing of Collins and Crane and often paid thousands of dollars for the privilege when they could easily pick up stories from unknown authors for a pittance?

If the quantity of sales achieved by syndicated fiction is not in doubt, what of the qualitative aspects of the readership? In an article in the Contemporary Review of April 1891, Edmund Gosse argued that, in the English-speaking world at least, newspapers were “the most democratic of all vehicles of thought” (532). This can be understood in two senses. Firstly, that the readership of newspapers in general represents all sorts and conditions of people, while the particular community of readers of any given newspaper reflects a rather wider social range than that of other genres of printed publication, whether in periodical or book form. Though Ouida snobbishly sees provincial newspapers as invariably reflecting “the preference of the vulgar,” in reality, by concentrating on a limited geographical area, the journals in which fiction was regularly syndicated typically appealed to a readership that crossed boundaries of class, gender, and even politics. Secondly, the miscellaneousness of material and the diversity of opinion found in the contemporary newspaper aptly reflected the complexity of modern society. It is worth remembering that Walter Bagehot, in an article on “Charles Dickens” published in the National Review in October 1858 (468), saw the modern writer’s genius as

. . . especially suited to the delineation of city life. London is like a newspaper. Everything is there, and everything is disconnected. There is every kind of person in some houses; but there is no more connection between the houses than between the neighbours in the lists of “births, marriages, and deaths.” As we change from the broad leader to the squalid police-report, we pass a corner and we are in a changed world. This is advantageous to Mr. Dickens’s genius. … He describes London like a special correspondent for posterity.

In this sense the newspaper, with its casual juxtaposition of news, comment, advertising, and entertainment, might be seen to represent a fitting venue for an encounter with the some of the most challenging imaginative writing of the day.

Effects of Syndication

As already suggested, Ouida’s claim that syndication was a new American commercial scheme forced on an unwilling English literary public was without foundation. Moreover, we need also to consider critically her assertion that the process was uniformly damaging to both the interests of the literary author and the integrity of the literary work. Forgetting that publishing houses were also “middlemen” whose discrete function in the circuit of publication only emerged during the eighteenth century, Ouida paints a naively nostalgic picture of a superseded “gentlemanly” regime of publishers, who recognized “the dignity and delicacy of art” and had interests identical to those of the writer. Until late in the Victorian period, however, and to the increasing frustration of progressive authors like Hardy and Gissing, major London literary publishers such as Bentley or Smith, Elder chose to tailor their wares to the prudish demands of the circulating libraries, whose select middle-class family readership was mirrored in that of their own house magazines, including Temple Bar and the Cornhill. Though Hardy’s Tess of the Durbervilles was rejected by Tillotson’s because of its frankness on sexual matters and only accepted by the Graphic in bowdlerized form, in his strictures on “Candour in Fiction,” the author had nevertheless insisted that one way of effecting the emancipation of the novel from the clutches of Mrs Grundy was to issue it not in “respectable” periodicals but “as a feuilleton in newspapers” (Hardy 20-1).

Furthermore, until the last decades of the nineteenth century, leading American publishing houses like Harper Brothers in New York and Ticknor and Fields in Boston were among the most resolute defenders of a copyright regime which at the same time encouraged the unauthorized reprinting of the work of writers overseas and depressed the rewards available to domestic authors. To the financial benefit of both British and American novelists, whether Arthur Conan Doyle or Henry James, the rise of the syndicates not only directly raised the remuneration from the sale of serial rights but also helped indirectly to bring about the passage of the Chace Act of 1891, which for the first time recognized the intellectual property rights of foreign authors. Moreover, the degree of commodification of the literary work brought about by the process of syndication, whether gauged in terms of the form of the writing or the social character of the readership, was typically less marked than that encountered under the succeeding regime of mass-market publications, whether flimsy paper-covered books or cheap story papers, issued by metropolitan publishing magnates.

The moment of the literary syndicates thus represented a relatively brief and rather unstable phase of transition between the production of fiction as a petty commodity for a limited bourgeois readership and its manufacture as a mass good for popular consumption. This process clearly offered gains as well as losses to authors, and it exposed the changing conditions of literary production in an especially interesting way. As we have seen, Ouida’s outrage in her lengthy letter to The Times in the spring of 1891 was by no means justifiable on rational grounds. All the same, it can serve as a telling symptom of the anxieties of authorship – particularly for those still committed to a romantic ideal of artistic inspiration such as Ouida (see Law, “Professionalization”) – during a period of rapid and radical economic transformation.

published March 2013

HOW TO CITE THIS BRANCH ENTRY (MLA format)

Law, Graham. “22 May 1891: Ouida’s Attack on Fiction Syndication.”BRANCH: Britain, Representation and Nineteenth-Century History. Ed. Dino Franco Felluga. Extension of Romanticism and Victorianism on the Net. Web. [Here, add your last date of access to BRANCH].

WORKS CITED

Bagehot, Walter. “Charles Dickens.” National Review 7 (1858): 458-86. Google Book Search. Web. 21 Aug. 2012.

Besant, Walter. “New Literary Factors.” The Times (26 May 1891): 8. Times Digital Archive (Cengage Learning). Web. 5 Jan. 2013.

Dill, William A. Growth of Newspapers in the United States. Lawrence: U of Kansas P, 1928. Print.

Donaldson, William. Popular Literature in Victorian Scotland: Language, Fiction and the Press. Aberdeen: Aberdeen UP, 1986. Print.

Eliot, Simon. Some Patterns and Trends in British Publishing, 1800-1919. London: Bibliographical Society, 1994. Print.

Gosse, Edmund. “The Influence of Democracy on Literature.” Contemporary Review 59 (1891): 523-36. Google Book Search. Web. 22 Aug. 2012.

Hardy, Thomas. “Candour in Fiction.” New Review 2 (1890): 15-21. Print.

Johanningsmeier, Charles A. Fiction and the American Literary Marketplace: The Role of Newspaper Syndicates in America, 1860-1900. Cambridge: Cambridge UP, 1997. Print.

Johnson-Woods, Toni. Index to Serials in Australian Periodicals and Newspapers: Nineteenth Century. Canberra: Mulini Press, 2001. Print.

Law, Graham. Serializing Fiction in the Victorian Press. Houndmills: Palgrave, 2000. Print.

—. “Savouring of the Australian Soil?: On the Sources and Affiliations of Colonial Newspaper Fiction.” Victorian Periodicals Review 37 (2004): 75-97. JSTOR. Web. 29 Oct. 2012.

—. “Imagined Local Communities: Three Victorian Newspaper Novelists.” Printing Places. Ed. John Hinks and Catherine Armstrong. New Castle: Oak Knoll P; London: British Library, 2005. 185-203. Print.

—. “The Professionalization of Authorship.” The Oxford History of the Novel in English: Vol. 3, The Nineteenth-Century Novel, 1820-1880. Ed. John Kucich and Jenny Bourne Taylor. Oxford: Oxford UP. 2011. 37-55. Print.

Lyon, Peter. Success Story: The Life and Times of S.S. McClure. New York: Scribner, 1963. Print.

“Ouida” [Marie Louise de la Ramée]. “New Literary Factors.” The Times (22 May 1891): 3. Times Digital Archive (Cengage Learning). Web. 5 Jan. 2013.

Pollard, Graham. “Serial Fiction.” New Paths in Book Collecting. Ed. John Carter. London: Constable, 1942. 247-77. Print.

Queffélec, Lise. Le roman-feuilleton français au XIXe siècle. Paris: PUs de France, 1989. Print.

Sinclair, Alexander. Fifty Years of Newspaper Life, 1845-1895. Glasgow: n.p., 1895. Print.

Turner, Michael L. “Reading for the Masses: Aspects of the Syndication of Fiction in Great Britain.” Book Selling and Book Buying: Aspects of the Nineteenth-Century British and American Book Trade. Ed. Richard G. Langdon. Chicago: American Library Association, 1978. 52-72. Print.

Watson, Elmo Scott. A History of Newspaper Syndicates in the United States, 1865-1935. Chicago: n.p., 1936. Print.