Abstract

This article examines the cultural and political significance of the Prince of Wales’s early 1780s involvement with Drury Lane actress and poet Mary Robinson. Rather than just a romance between two public figures, the “Florizel and Perdita Affair” had wide-ranging effects that, when examined, offer meaningful insight into everything from the weakening influence of the Hanover dynasty and the campaigns of Whig opposition candidates to the aesthetics of formal portraiture, political cartoons, and popular fashion.

![]() On 3 December 1779, Drury Lane staged David Garrick’s Florizel and Perdita (1756), an adaptation of Shakespeare’s The Winter’s Tale. Before the curtain rose, little did actress Mary Robinson (who played Perdita) or the Prince of Wales (who attended the performance) know that this night would have a lasting and profound impact on their private lives and public reputations. Florizel and Perdita was a command performance, so not only were George III and Queen Charlotte present, the 17-year-old Prince (later George IV) occupied his reserved box located in close proximity to the stage. So close, in fact, that when Robinson began to speak her lines, she could hear the Prince’s “flattering remarks,” and he could see how she “blushed with gratitude” when she heard them (The Memoirs 102). By his own account, the impetuous Prince had given way to “strong and lively passions” by the next day, declaring Robinson to be “the greatest and most perfect beauty of her sex” (Anson Papers, Prince to Mary Hamilton, letter 74. Quoted in Perdita 100-101). Through the embassy of Lord Malden, he began epistolary overtures to Robinson, addressing her as “Perdita” and signing himself as “Florizel,” Perdita’s princely lover in the play. Robinson kept up the correspondence, but she did not agree to meet the Prince personally until he offered her a bond of £20,000, ostensibly meant to compensate Robinson for the loss of reputation and professional opportunities she would suffer once the affair became known. Historical currency conversion is tricky, but the promised £20,000 is equivalent to about £2 million or 3 million US dollars in 2012. (“Six Ways to Compute the Relative Value” n. pag.) This offer, apparently too good to refuse, resulted in the pair enjoying their first assignation in June 1780 at the inauspiciously named

On 3 December 1779, Drury Lane staged David Garrick’s Florizel and Perdita (1756), an adaptation of Shakespeare’s The Winter’s Tale. Before the curtain rose, little did actress Mary Robinson (who played Perdita) or the Prince of Wales (who attended the performance) know that this night would have a lasting and profound impact on their private lives and public reputations. Florizel and Perdita was a command performance, so not only were George III and Queen Charlotte present, the 17-year-old Prince (later George IV) occupied his reserved box located in close proximity to the stage. So close, in fact, that when Robinson began to speak her lines, she could hear the Prince’s “flattering remarks,” and he could see how she “blushed with gratitude” when she heard them (The Memoirs 102). By his own account, the impetuous Prince had given way to “strong and lively passions” by the next day, declaring Robinson to be “the greatest and most perfect beauty of her sex” (Anson Papers, Prince to Mary Hamilton, letter 74. Quoted in Perdita 100-101). Through the embassy of Lord Malden, he began epistolary overtures to Robinson, addressing her as “Perdita” and signing himself as “Florizel,” Perdita’s princely lover in the play. Robinson kept up the correspondence, but she did not agree to meet the Prince personally until he offered her a bond of £20,000, ostensibly meant to compensate Robinson for the loss of reputation and professional opportunities she would suffer once the affair became known. Historical currency conversion is tricky, but the promised £20,000 is equivalent to about £2 million or 3 million US dollars in 2012. (“Six Ways to Compute the Relative Value” n. pag.) This offer, apparently too good to refuse, resulted in the pair enjoying their first assignation in June 1780 at the inauspiciously named ![]() Eel Pie Island, not far from

Eel Pie Island, not far from ![]() Kew. Reports of the affair’s length vary. It ended at the earliest in December of 1780 and at the latest sometime in 1781 (“Making an Exhibition of Her Self” 272 and Royal Romances 15). During their courtship, the Prince gave Robinson a miniature locket of himself set with brilliants. Inside, there was a paper heart inscribed with the words “unalterable to my Perdita through life” and, just in case he was unclear, “Je ne change qu’en mourant” (“constant until death”) on the reverse. Yet, despite his protestations of fidelity, the Prince moved on to a new beauty, the famous courtesan Elizabeth Armistead, in 1781. To end the relationship with Robinson, he wrote an unceremonious termination letter, saying simply “we must meet no more!”—a far cry from his early histrionic epistles (The Memoirs 115).

Kew. Reports of the affair’s length vary. It ended at the earliest in December of 1780 and at the latest sometime in 1781 (“Making an Exhibition of Her Self” 272 and Royal Romances 15). During their courtship, the Prince gave Robinson a miniature locket of himself set with brilliants. Inside, there was a paper heart inscribed with the words “unalterable to my Perdita through life” and, just in case he was unclear, “Je ne change qu’en mourant” (“constant until death”) on the reverse. Yet, despite his protestations of fidelity, the Prince moved on to a new beauty, the famous courtesan Elizabeth Armistead, in 1781. To end the relationship with Robinson, he wrote an unceremonious termination letter, saying simply “we must meet no more!”—a far cry from his early histrionic epistles (The Memoirs 115).

This brief affair reads like a fairly routine rehearsal of fashionable life. Actresses, most notably Nell Gwynn (Charles II), Dorothy Jordan (Duke of Clarence, later William IV) and Sarah Bernhardt (Edward VII), were often mistresses to royalty from the Restoration onward (“Public Life of Actresses” 59-67). Yet, the implications of the “Florizel and Perdita” affair go far beyond biographical interest. The affair provides a high-profile entrée into thinking about the role of intertextuality and celebrity, scandal’s influence in politics, and debates about women’s role in the public sphere. Rather than a series of private trysts, the affair was highly public, inspiring countless gossip columns, political cartoons, two epistolary novels, and compositions for formal portraiture (Royal Romances 15-45). The Prince’s desire to flaunt his “gallant” (an eighteenth-century euphemism for “promiscuous”) lover at official venues provided rich fodder for the letters of the fashionable and powerful at a time when the Hanovers were seen as particularly weak. Royal authority had eroded tremendously under the previous king, George II (1727-1760), who ceded power to Whig ministers such as Robert Walpole, and allowed their influence to increase markedly during his reign.

Although the definition of “Whig” and “Tory” varies considerably over the course of the eighteenth century, in general terms, one can think of Whigs as invested in constitutional authority and representative government, albeit limited to an elite class of propertied men. The term “Tory” was used to denote a politician who promoted the legitimacy of the hereditary power exercised by the monarch and emphasized the need for subjects’ loyalty and obedience to the crown (“Whig versus Tory” 455-69). George III, the present king (1760-1820), had tried to regain much of this hereditary power, but by 1779, his reign had already seen its share of failures, including a ministerial crisis (1761-62) soon after his coronation, the Stamp Act debacle (1765-66), and the start of the disastrous American Revolution (1775-83) (George III 1-6, 71-95). Whig opposition politicians used these and other points of weakness to oppose George III’s desire to extend the royal prerogative.

Within this context, the Prince did not appear a terribly fit successor in opposing Whig ministers; in fact, he rebelled early on against his father’s positions and created alliances with Whig parliamentarians (George III 153-4). As an inexperienced adolescent who demonstrated an early predilection for debauchery, he also provided ammunition for political opponents seeking to dismiss an increasingly expensive and inept monarchy. Thus, Robinson’s thinly veiled threat to sell their love letters to a newspaper if she did not receive her promised settlement created a flurry of negotiations between her and the monarchy (Empowering the Feminine 28). Still in his minority, the Prince could not truly negotiate a settlement, and George III’s letters demonstrate his shame and rage about the unforeseen expense (Perdita 153). In the end, Robinson received only a quarter of the sum the Prince had promised—£5,000—in exchange for the letters and perhaps her silence. Although the Crown considered the matter done, spendthrift Robinson continued throughout her lifetime to request money from George IV with varying degrees of success. In short, the “Florizel and Perdita” affair had a life of its own that made and ruined the prospects of many beyond just the two lovers, provided ammunition to discredit the Hanovers and to criticize the Prince’s growing allegiance to the Whig party, and established the career of one of the Romantic era’s most maligned celebrities, yet most celebrated women writers.

“Florizel and Perdita” as Political Propaganda

Once the content of the Prince’s imaginative letters was leaked, the pair was henceforth known as “Florizel and Perdita.” Although using the pseudonym allowed the Prince to maintain anonymity, it also underscored the ease with which spectators conflated actors and characters. The Prince extended the fantasy of the playhouse into the bedroom, and the press picked up on this private fantasy as a way to characterize the Prince’s future role as a politician and Robinson’s enduring reputation. Although the public enjoyed lingering on the prurient details of the affair, they also used them to create a series of paratexts that give insight into Romantic culture more generally.

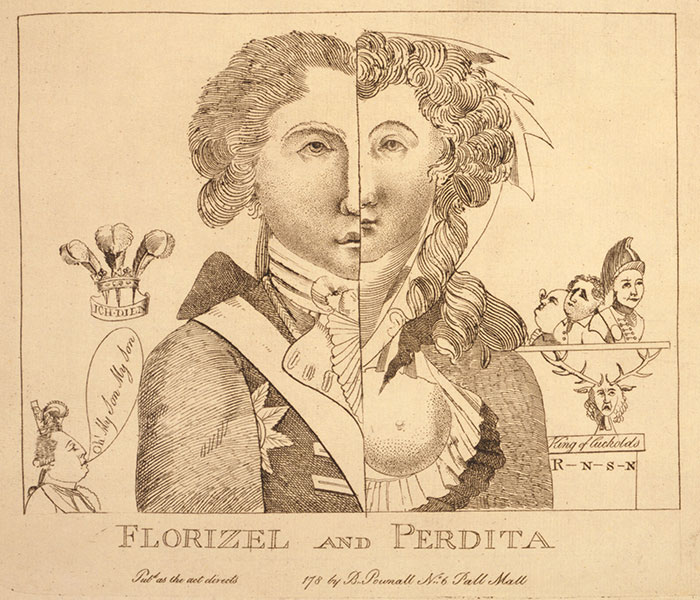

Figure 1: Florizel and Perdita (![]() Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Edition)

Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Edition)

The caricatures of “Florizel and Perdita” were almost exclusively political in nature. Perhaps the most famous, “Florizel and Perdita” (1783), depicts the Prince, now officially recognized as heir-apparent, and Robinson as two halves of one whole person (Fig. 1). On the Prince’s side, George III appears, lamenting, “Oh My Son My Son!” On Robinson’s side, her husband Thomas Robinson is depicted as “King of Cuckolds,” balancing the plated heads of Mary’s other conquests—recognizably Banastre Tarleton and Charles James Fox, and possibly Lord Malden—on his horns. As with all caricature, the artist uses a heavy hand to hammer home his main point: the Prince is a licentious fool, unfit to rule. Robinson is a shameless courtesan who has humiliated not only her husband but also the future King with her incontinence and inconstancy.

The image, however, conveys many other, more nuanced suggestions, which its contemporary audience would have recognized. Representing Robinson and the Prince as two halves of one whole, even though their affair ended two years prior, suggests that they both are indelibly marked by the relationship. Her influence has set him on the path of debauchery, which he will follow wholeheartedly throughout his lifetime. Her bare breast, along with her many pictured lovers, suggests her universal availability, yet because this breast is half George’s, he appears highly feminized and degraded himself. Robinson’s other pictured conquests—a celebrated colonel, the current Foreign Secretary, and a connected parliamentarian—are all prominent Whigs. Their appearance on Robinson’s platter suggests that these other “heads of state” should not occupy leadership positions; clearly their metonymic “heads” are occupied elsewhere. “The vis-à-vis of Berkeley Square,” a satiric poem published in 1783, echoes the caricature’s sentiments in comic verse:

The Prince, the Pickpocket, and Clown,

All stare at Phryne’s [Robinson’s] station!

The very stones look up, to see

Such very gorgeous Harlotry

Shaming a foolish Nation! (19)

Here the author suggests that everyone—from the lofty Prince to a personified humble stone on the ground—has become spellbound by what is under Robinson’s skirts. The satirist suggests that beyond demonstrating licentiousness, the general fascination with Robinson’s “harlotry,” or genitals, reveals a people distracted from their important business in ways that have political consequences by “shaming [the] Nation.” From 1779-1783, England had endured the Gordon Riots, the loss of the American colonies, and an ongoing war with the Dutch—serious matters that, according to the poet, deserved more attention than Mary Robinson. Other pictorial caricatures—including “The Thunderer,” “Paradise Regain’d,” “The new vis-à-vis, or Florizel driving Perdita,” “The Goats Canter to Windsor or the Cuckolds Comfort,” and “The Adventure of Prince Pretty Man”—use bawdy images to make similar arguments, demonstrating the constant suggestion that the sex lives of the Prince and other political figures had an important influence on their political efficacy.

As the Tory caricatures suggest, the men’s shared activity with Robinson’s body literalizes the connection between the Whig opposition to George III and the Prince’s growing sympathy with those politicians. In fact, the Prince publicly supported his father’s greatest enemy and Robinson’s other lover, Charles James Fox, during this period. When Fox was re-elected to parliament after being dismissed as First Lord of the Treasury by George III, the Prince celebrated in a public parade and hosted two lavish parties in honor of Fox (George IV 36-7). Yet early on the “Florizel and Perdita” affair was invoked for other political purposes, some of which run contrary to the suggestions of the later caricatures. In “The Poetic Epistle from Florizel to Perdita” (1781), an apocryphal versification of the Prince’s letters, the author included a highly political preface, a “Preliminary Discourse upon the Education of Princes,” which argues that it was Elizabeth Armistead, the Prince’s new mistress, who was facilitating the Prince’s Whig sympathies. As Paula Byrne notes, in this pamphlet Robinson “is held up as the very model of political orthodoxy” whereas Armistead is positioned as the “factious representative” of the “blue and buff Junto” (135). (Blue and buff were the recognizably branded colors of the liberal wing of the Whig party.) Here Robinson, the “ministerial candidate,” is characterized as a martyr to conservatism, whose love affair was sabotaged by power hungry Whigs desiring to end her influence over the young George. This interpretation is highly specious. Robinson later campaigned for Charles James Fox along with the Duchess of Devonshire, aligning herself ideologically with the Whigs. She even wrote poems for the pro-Fox Morning Herald in praise of her chosen candidate and his followers. Yet, what I want to emphasize here is that her image was in the public domain, and her affair with the Prince was deployed to fulfill a variety of political ends. This (most likely) six-month affair had a much longer afterlife as grist for the political mill.

The Making of “Perdita”

While both the Prince and Robinson moved on to new conquests in 1781, Mary’s moniker “Perdita” was attached to her until her death in 1800. She was not, however, a victim of this notoriety (“Making an Exhibition” 276-302). Rather, like her predecessor Nell Gwynn, Robinson made a name for herself in part by publicizing her sexual connection with royalty. As we learn from her Memoirs (posthumous 1801), Robinson did not always live like the party girl depicted in the scandal sheets and gossip columns. When she met the Prince she was married, had one living daughter (Maria Elizabeth), had experienced the death of another (Sophia) in infancy, and had suffered at least one miscarriage. According to most accounts, her husband Thomas was a profligate who constantly dogged his wife for money to pay gambling debts, keep mistresses, and fuel a drinking habit. In caricatures and published pamphlets, some even alleged that Thomas acted as Mary’s procurer, forwarding her connections to important men to finance his rakish lifestyle. Thomas Rowlandson’s “![]() Vauxhall Pleasure Gardens” depicts Thomas discretely staying to Mary’s side as she flirts with the Prince (Fig. 2). When Mary met the Prince, it was public knowledge that Mr. and Mrs. Robinson lived apart. Robinson alleges in her Memoirs that it was under these conditions—inundated with Princely affection and ignored by her husband—that she strayed from her marriage vows:

Vauxhall Pleasure Gardens” depicts Thomas discretely staying to Mary’s side as she flirts with the Prince (Fig. 2). When Mary met the Prince, it was public knowledge that Mr. and Mrs. Robinson lived apart. Robinson alleges in her Memoirs that it was under these conditions—inundated with Princely affection and ignored by her husband—that she strayed from her marriage vows:

The unbounded assurances of lasting affection which I received from his Royal Highness in many scores of the most eloquent letters, the contempt which I experienced from my husband, and the perpetual labour I underwent for his support, at length began to weary my fortitude. (107)

The reality, of course, is less flattering and much more complicated than Robinson’s self-representation. Mary and Thomas Robinson remained in debt throughout their marriage—due in part to his profligacy and her attraction to the bon ton. Mary and Maria Elizabeth even accompanied Thomas for a 15-month stint in ![]() The Fleet, a debtor’s prison, in 1775. Paula Byrne’s extensive biography of Robinson makes a strong case that Mary was leveraging her beauty to pay the bills long before she met the Prince (27-94).

The Fleet, a debtor’s prison, in 1775. Paula Byrne’s extensive biography of Robinson makes a strong case that Mary was leveraging her beauty to pay the bills long before she met the Prince (27-94).

In appropriating the persona of “Perdita,” Robinson might have seen an opportunity to forego both licit and illicit forms of “perpetual labor” to support her family (The Memoirs 107). Robinson partly grounded this persona in its theatrical origins. Even though she had left the stage a year earlier, she sat for a costume portrait for John Hoppner in that signature role: “Perdita” (1782). (See Fig. 3.) Theatre managers David Garrick and Richard Brinsley Sheridan also promulgated this offstage role to increase the profits of Drury Lane (“Garrick’s Version” 125-38). The most important early portrait for thinking about the “Florizel and Perdita Affair,” however, is Thomas Gainsborough’s Mrs. Mary Robinson—Perdita (1781), a stunning visual commemoration of the real Robinson’s liaison with the Prince (Fig. 4). The affair’s timing affects how one reads the portrait. Anne K. Mellor suggests that Gainsborough painted it for the Prince of Wales in 1781 (278). Read in that context, Gainsborough’s work memorializes sexual role play for his patron, Perdita’s Florizel. Paula Byrne offers a more complicated timeline, acknowledging that the portrait was “apparently commissioned by the Prince” but noting that the timing for such a commission coincides with a period in which “he was trying to expunge her [Robinson] from his life” (154-5). Byrne reconciles this seeming contradiction by positing the portrait’s role as a “souvenir” eventually hung at ![]() Carlton House, yet she also notes that the Prince did not begin paying Gainsborough’s widow for the portrait until 1793 (155). This delay in payment, at the very least, suggests that the Prince’s nostalgia did not develop until bitter memories over the intense settlement negotiations had faded. It is also possible that Robinson’s willingness to be depicted as Perdita was a calculated public relations strategy meant to bolster her celebrity after she had lost her royal connection.

Carlton House, yet she also notes that the Prince did not begin paying Gainsborough’s widow for the portrait until 1793 (155). This delay in payment, at the very least, suggests that the Prince’s nostalgia did not develop until bitter memories over the intense settlement negotiations had faded. It is also possible that Robinson’s willingness to be depicted as Perdita was a calculated public relations strategy meant to bolster her celebrity after she had lost her royal connection.

Gainsborough’s composition deploys body, costume, and background to signal Robinson’s history of playing Perdita at Drury Lane Theatre and playing “Perdita” as the Prince’s erstwhile mistress. As with many of her early portraits, Robinson gazes directly and alluringly at the viewer. At the same time, the viewer’s counter-gaze is invited by the spectacle of her beauty—porcelain skin offset with blushing cheeks, rosebud lips, and an exposed foot and ankle. The pastoral background and accompanying dog allude to Robinson’s theatrical role as the incognita shepherdess. Within her tapered fingers, she holds the Prince’s recognizable miniature portrait in one hand and a handkerchief in the other. These props suggest that the real-life Robinson has been weeping for her lost lover, and create a lasting visual record of the short affair. The gift of the miniature was highly publicized as proof of George’s constancy, so Robinson’s grief while holding it suggests a tacit condemnation of the Prince’s abandonment. This seemingly small detail anticipated the significance the miniature would have for Robinson throughout her lifetime. In fact, when the Sheriff of ![]() Middlesex seized her goods for auction in 1784, another portrait of Robinson was sold for 30 guineas, but Robinson managed to hold on to the king’s miniature until her death (Perdita 232). Her tenacious grasp on this object during subsequent years of financial struggle suggests that the miniature was as vital to her self-image as Gainsborough’s composition implies. The Gainsborough portrait kept Robinson’s royal associations fresh in the public mind, despite the fact that she had moved on to less illustrious lovers (Lord Malden and Colonel Banastre Tarleton) soon after the breakup. Yet, the portrait characterizes Robinson as Perdita “the lost one,” rather than as the opportunistic fortune hunter many believed her to be. Despite the obvious imbalance of power in the Prince’s favor, some suggested that a scheming older woman, the twenty-four-year-old Robinson, had victimized the innocent seventeen-year-old Prince (Perdita 118).

Middlesex seized her goods for auction in 1784, another portrait of Robinson was sold for 30 guineas, but Robinson managed to hold on to the king’s miniature until her death (Perdita 232). Her tenacious grasp on this object during subsequent years of financial struggle suggests that the miniature was as vital to her self-image as Gainsborough’s composition implies. The Gainsborough portrait kept Robinson’s royal associations fresh in the public mind, despite the fact that she had moved on to less illustrious lovers (Lord Malden and Colonel Banastre Tarleton) soon after the breakup. Yet, the portrait characterizes Robinson as Perdita “the lost one,” rather than as the opportunistic fortune hunter many believed her to be. Despite the obvious imbalance of power in the Prince’s favor, some suggested that a scheming older woman, the twenty-four-year-old Robinson, had victimized the innocent seventeen-year-old Prince (Perdita 118).

Portraiture was just one of the many visual strategies Robinson employed to shape her persona at this period. She also staged public appearances and manipulated fashionable dress to maintain status in the post-Prince era. Robinson read the scandal sheets and actively responded to their critiques. For example, when the Morning Herald used military imagery to characterize her rivalry with her successor, Elizabeth Armistead, Robinson showed up in a military-inspired costume to a masked ball attended by the Prince. This dress served multiple functions. It signaled to the Prince, the press, and the public Robinson’s awareness of the characterization, demonstrated her ability to rise to the occasion—to be “in” on the joke—and appropriated the discourse for use in fashion, an area in which she was adept. In fact, her unusual dress caused that same paper to give her more publicity after the ball, describing her unusual costume as “en militaire, regimentally equipped from top to toe” (Morning Herald, May 4, 1781 quoted Perdita 142).

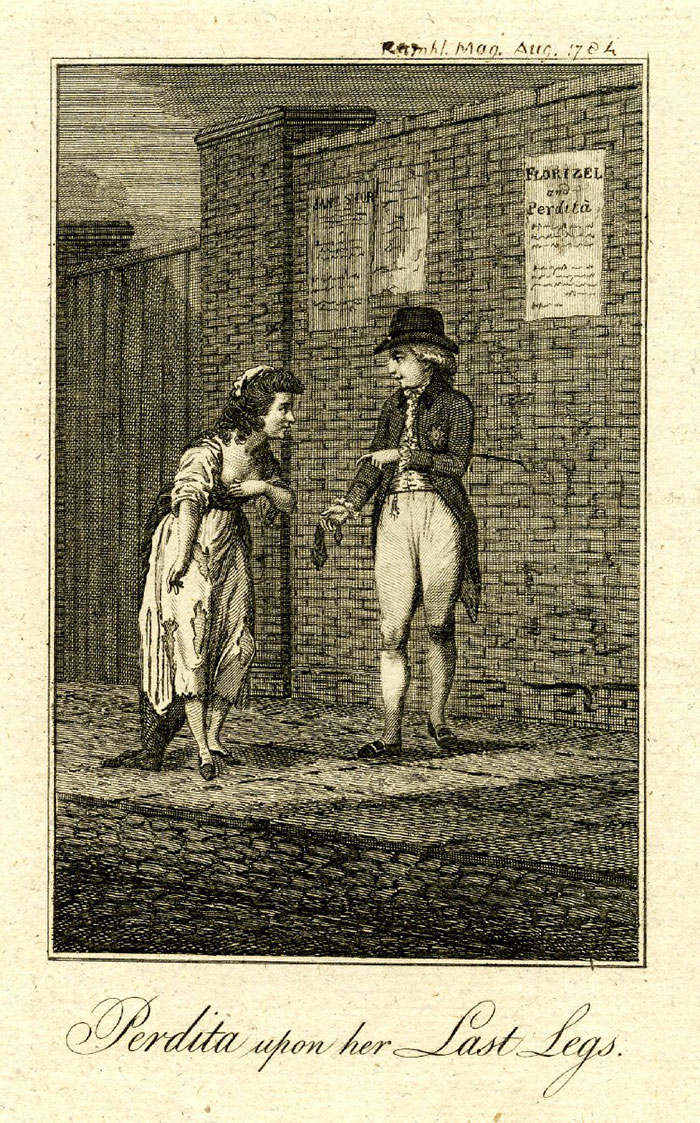

In 1783, Robinson suffered from a rheumatic fever that partially paralyzed her, eventually caused her death, and made it difficult for her to continue capitalizing on her sexuality. As Michael Gamer and Terry Robinson note, it took Robinson several years to re-invent herself as an author, an intellectual, and a devoted mother (“Mary Robinson” 219-56). Initially, she adapted her visual strategies to her changed physical condition, famously riding about London in spectacular carriages to still appear as one of the beau monde. Joshua Reynolds’s second portrait of her (1783) from this period offers one of the more luscious depictions of her neck and décolletage even as her profiled expression is Romantic and introspective. Still marketing herself visually as a sex symbol, Robinson left herself open to ongoing ribald caricatures, most famously “Perdita upon her Last Legs” (1784). (See Fig. 5.) Here, Robinson is depicted as a streetwalker in rags accepting a bag of money from the Prince. The artist suggests that Robinson’s disability, crudely referred to as her “last legs,” is caused by venereal disease, rather than rheumatism, and that she can only now beg for the male favor she once commanded. Two playbills are discernible in the background. One in the shadows announces a performance of Nicholas Rowe’s famous she-tragedy Jane Shore (1714), thereby mocking Mary’s role as an adulteress and alluding to the historical Shore who was mistress to Edward IV in the fifteenth century. Highlighted in the foreground is another bill for Garrick’s Florizel and Perdita, which serves to identify easily the figures depicted but also to suggest that Robinson has been supplanted by another actress in her signature role. Clearly, the Perdita shown here is the cast-off courtesan, not the beauty playing the incognita princess in the advertised performance.

An expert at self-representation, Robinson eventually realized that literary, rather than visual, rhetorical strategies proved the most effective means of reinvention, and through her role as a poet, novelist, and journalist, she was able to take back control of the conversation about her image. Her new image was not one persona, but many, lessening the importance of the “Florizel and Perdita” affair to her overall self-fashioning. As Gamer and Robinson note, her Memoir “present[s] her in the full range of guises, from devoted mother and woman of feeling to wronged heroine and natural poetic genius” (243). These roles are reflected by many aliases such as “Sappho,” “Laura,” and “Tabitha Bramble,” and the associations they invoke. In print, she could masquerade in ways for which her well-known face and suffering body would not allow.

Robinson never fully rid herself of the “Perdita” persona, a fact made evident by three of the most recent biographies of her going by that title: Hester Davenport, The Prince’s Mistress, Perdita: A Life of Mary Robinson (2011); Paula Byrne’s Perdita (2005); and Sarah Gristwood, Perdita: Royal Mistress, Writer, Romantic (2005). Yet, Robinson also went on to become a well-known and aesthetically influential poet and novelist—a topic which will, no doubt, be explored in a subsequent BRANCH entry. She never stopped struggling to earn a living, and she died with only her daughter attending her in an obscure cottage in 1800. Becoming “Perdita” did not solve her financial problems or help her to support her family in the way she had hoped. This disappointment explains, in part, Robinson’s participation in the early feminist movement. Under another pseudonym, Anne Francis Randall, she published A Letter to the Women of England, on the Injustice of Mental Subordination (1799) a year before her death. The main critique of the Letter is the persistence of the sexual double standard and a woman’s inability to recoup or to defend her own reputation—an inability that severely hampered Robinson’s economic survival once her affairs with prominent men ended.

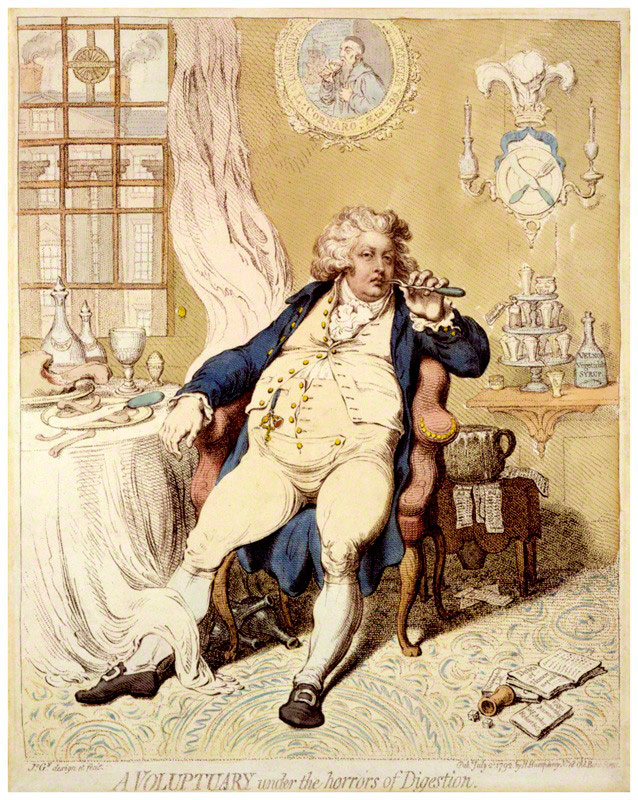

The Prince, of course, went on to become Regent and then King, but the type of sensual license he indulged in with Robinson shaped his entire life, as he became a notorious womanizer and drinker and incurred enormous debts. James Gillray’s “A Voluptuary” (1792) best memorializes popular perceptions of his debauched physique and bankrupt morals. (See Fig. 6.) The lovers’ ends are sad in different ways; yet, focusing on the aftermath of that fateful night at Drury Lane in 1779 provides important insight into how the proliferation of print and visual images of the affair shaped depictions of the Prince’s emerging politics and conversations about celebrity and women’s role in the public sphere. Not simply an “affair” in the colloquial sense, the brief love of the Prince and Robinson electrified a zeitgeist teeming with politically and sexually revolutionary rhetoric.

published March 2013

HOW TO CITE THIS BRANCH ENTRY (MLA format)

Ledoux, Ellen Malenas. “Florizel and Perdita Affair, 1779-80.” BRANCH: Britain, Representation and Nineteenth-Century History. Ed. Dino Franco Felluga. Extension of Romanticism and Victorianism on the Net. Web. [Here, add your last date of access to BRANCH].

WORKS CITED

Barbour, Judith. “Garrick’s Version: The Production of Perdita.’” Women’s Writing 9:1 (2002): 125-138. Print.

Black, Jeremy. George III: America’s Last King. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2006. Print.

Burrows, Barry M. “Whig versus Tory-A Genuine Difference?” Political Theory 4:4 (Nov. 1976): 455-469. Print.

Byrne, Paula. Perdita: The Literary, Theatrical, Scandalous Life of Mary Robinson. New York: Random House, 2004. Print.

Crouch, Kimberly. “The Public Life of Actresses: Prostitutes or Ladies?” Gender in Eighteenth-Century England: Roles, Representations, and Responsibilities. Ed. Hannah Barker and Elaine Chalus. London: Longman, 1997. 58-78. Print.

Gamer, Michael and Terry F. Robinson. “Mary Robinson and the Dramatic Art of the Comeback.” Studies in Romanticism 48 (2009): 219-56. Print.

Hibbert, Christopher. George IV: Prince of Wales 1762-1811. New York: Harper and Row, 1972. Print.

Mellor, Anne K. “Making an Exhibition of Her Self: Mary ‘Perdita’ Robinson and Nineteenth-Century Scripts of Female Sexuality.” Nineteenth-Century Contexts 22:3 (2000): 271-304. Print.

Officer, Lawrence H. and Samuel H. Williamson, “Six Ways to Compute the Relative Value of a U.K. Dollar Amount, 1270 to present.” MeasuringWorth.com. March 2011. Web. 3 September 2012.

Robinson, Mary and Maria Elizabeth Robinson. Perdita: The Memoirs of Mary Robinson. Ed. M.J. Levy London: Peter Owen, 1994. Print.

Samuelian, Kristin Flieger. Royal Romances: Sex, Scandal, and Monarchy in Print, 1780-1821. New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2010. Print.

The vis-à-vis of Berkley Square; or, a Wheel off Mrs. W*t**n’s carriage. Inscribed to Florizel. London: Murray, 1783. ECCO. Web. 5 November 2012.

Ty, Eleanor. Empowering the Feminine: The Narratives of Mary Robinson, Jane West, and Amelia Opie, 1796-1812. Toronto: U of Toronto P, 1998. Print.