Abstract

Robert Browning’s Men and Women, a two volume publication of new poems, was a major literary event in nineteenth-century Britain. These poems shift emphasis from the private, atemporal, and generally non-social genre of Romantic lyricism to the ironies and enigmas of human awareness and social relationships, to dramatic action in human speech. Browning’s men and women are presented overtly as speech acts, grounded in psychological and cultural origins, and in the ambiguities of linguistic processes. Readers often found Browning’s mode of writing obscure, but its methods and implications consistently engage with other domains of Victorian thought—in religion, biology, and psychiatry. While the status of this publication was not widely understood at the time, its value is manifest in its reception history, in the discussion and representations that constitute its ongoing existence as a historical event.

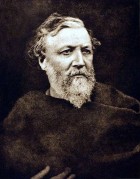

In November 1855 Robert Browning published 51 new poems under the general title of Men and Women. Browning had high hopes for their success, but if an “event” exists only in its representations—discussion, debate, description, the marks that generate its existence—this publication was at the time a minor moment. The two volumes were hardly noticed, barely debated in public and, apart from a few significant admirers (William Morris, the Rossettis, George Eliot), generally dismissed as yet another in a series of obscure works by the enigmatic Mr. Browning (DeVane 205-11; Ryals 132-33; Kennedy and Hair 274-81). It is only by means of their reception history, their public discussion and analysis in the following decades and century, that their cultural and aesthetic value gradually emerged. Ensuing judgements have subsequently defined this event as a watershed in Browning’s career, as among the best three of his publications, along with Dramatis Personae (1864) and The Ring and the Book (1868-69), and as a major moment therefore in the literary history of nineteenth-century Britain.

The 51 poems in the publication include all those that have become synonymous with the best in Browning’s art, including his major monologues—“Andrea del Sarto,” “Fra Lippo Lippi,” “Bishop Blougram’s Apology,” “Cleon,” “An Epistle Containing the Strange Medical Experience of Karshish, the Arab Physician,” “‘Childe Roland to the Dark Tower Came’”—his most celebrated lyrics—“Two in the Campagna,” “Love Among the Ruins,” “The Last Ride Together,” “By the Fireside” —and his two famous music poems—“Master Hugues of Saxe-Gotha” and “A Toccata of Galuppi’s.” By themselves these pieces have become major works in the language, but in the context of their time and culture, these and the other works in the set also focus a fascinating development in British literary history. An explanation of that development needs to include an account of the generic and linguistic challenge of the works as well as an account of the major intellectual and cultural moods of the period. The burgeoning growth of polemical journals, public papers, private letters, three-volume novels, biographies and apologias, and the spread of popular literature following the invention of cheap paper, meant that nineteenth-century Britain became a golden age of letters. Before radio and television, major public debate took place in journals and the press. Discursive materials and methods characterized therefore the basis of thriving cultural activity, and in the context of this acute dialectical energy, Robert Browning was its major poetic representative, dramatizing its ambiguities, its ironies, and verbal enigmas.

Victorian poets and their readers inherited from their immediately Romantic predecessors an emphasis on lyrical modes, where lyricism proposed a timeless moment, an expression of feeling and perception whose value and insights are outside, transcending, the temporal limits of daily life. By means of sheer figurative intensity such poems provided a glimpse of universal truth and beauty in the same way that Keats’s Grecian urn may “tease us out of thought” (44). Readers expected to benefit from these expressive moments, gleaning insights into universals, admiring the apprehension of universal beauty, and of course admiring the subtlety and brilliance of the individual poetic mind that could generate such understanding. In personalized lyricism, the biological poet was assumed to be the speaker in the poem, although the lyrical voice in the nineteenth century tended to be thought of generically as universal, idealist, and male.

For materialists, however, or for those for whom economic and political power were the key social issues, such aesthetic endeavors were of marginal interest, offering experiences only on the fringes of human society, on areas related to spiritual or mental abstractions. Serious thinkers had more important issues to deal with, such as free trade, laissez faire economics, slavery, industrialization, class conflict, and political representation. This growing separation of poetry from social or political contexts was also reinforced by John Stuart Mill’s famous distinction in 1833 between rhetoric, which was “heard,” and poetry, which was “overheard” (Tucker, “Monologue”). Mill’s definition was the culmination of a long and gradual separation of rhetoric, or direct social discourse, from poetry as an aesthetically private experience defined by the lyric rather than the epic (Eagleton 12-16). But it was effectively what Isobel Armstrong has called a “poetics of exclusion” (137), denying poetry access to public experience and knowledge, declaring it a non-social genre. This exclusion was reinforced by the Romantic tendency to turn inwards. As they looked to their own emotional and mental lives for their moments of transcendent truth, Romantic poets located much of their poetry in some isolated spot, away from the intrusions and distractions of other people. Speakers in odes to autumn, nightingales, and skylarks or in hymns to Intellectual Beauty tend to talk alone, or to express a relationship with the wider world of natural phenomena rather than the world of people and social interaction.

Emphasis in poetry on the value of the individual mind was also linked with a widespread cultural obsession with introspection or self-scrutiny (Shaw, Lucid 47-74; Faas 57-62). Truth, it was believed, may be known by looking within: such was the long standing influence of the Cartesian formula cogito ergo sum (“I think therefore I am”) and its various combinations with German idealism in the early part of the nineteenth century. At the same time, among some social commentators suspicions were growing about the emotional excess and self-indulgence that seemed to be a side-effect of these methods, and embryonic psychology began to contest established views about madness and the function of reason. In mental studies concepts of insanity were revised to include a deluded imagination or disrupted moral perception, and in poetry several writers began to sense that the human potential for apprehending transcendent truths, for rending the veil of material reality by means of imaginative splendour (Shaw, Lucid), may as easily deploy that same imaginative splendour for fantasies of self-justification and gratification. This realization took many forms, as might be expected, but one response was to explore a variant poetic tradition of prosopopoeia, or impersonation, a mode of writing where the speaker is not the poet. Several poets in the early part of the century, including women poets such as Felicia Hemans and Letitia Landon, began to employ this tradition, writing poems whose speakers were demonstrably not the poet. In the 1830s, Alfred Tennyson and Robert Browning had both written youthful poems (“Ulysses” and “Porphyria’s Lover” respectively) that have become iconic examples of this form. In poems where speaker and biological author are distinct, and where the immediate social circumstances of the speaker loom large (Ulysses’s dull life back in Ithaca, or Porphyria’s different social class from her lover), aesthetic effects become intertwined with material conditions, universality and transcendence are immersed in the contingent and temporal, and any hint of an auditor makes the monologue fundamentally social, to do with interpersonal relationships and all that follows (desire, politics, power). Something was happening to poetic modes in the middle of nineteenth-century Britain that both poets and critics named as “dramatic,” and in 1855 Browning’s two-volume publication was at the centre of this developing practice.

The main innovative function of Men and Women, then, is indicated by its title. While novels had been dramatising the social processes of speakers for nearly a century, that was not true of poetry. And while the techniques of prosopopoeia were not new (neither prior to the Romantics nor among earlier poems in the nineteenth century), Browning in Men and Women places his whole emphasis on the portrayal of separate voices. In the final poem “One Word More: to E.B.B.,” the one poem that is not dramatized as a separate voice, he addresses his wife, Elizabeth Barrett Browning:

Love, you saw me gather men and women,

Live or dead or fashioned by my fancy,

Enter each and all, and use their service,

Speak from every mouth,—the speech, a poem.

(129-132)

He is aware therefore that unlike traditional lyric poets he does not speak in his own “true person” (137). Instead he speaks as if from the mouths of others, and it is this simulated “speech” that constitutes the poem. In the 1850s “dramatic poetry” was an undefined genre, and in later publications Browning himself separated his 1855 poems into variant categories—dramatic lyrics, dramatic romances, men and women. While the number of poems from 1855 that he retained in the later “Men and Women” section was relatively few, the chosen title for 1855, Men and Women, nevertheless focuses significant features of his mode of dramatic writing: the articulation (speech) of intensive moments of human feeling, and individual experience in relation to social contexts or psychological origins. Idealist truth in such a mode becomes inseparable from its material moment: belief and moral justification inseparable from emotional impetus and personal need. There are uncertainties of definition and distinction abounding in these linkages, and they were radical portrayals in the context of orthodox belief systems, and yet they were also entirely consistent with radical thinking in other Victorian domains—geology, biology, mental health, Biblical scholarship, German higher criticism, crises of faith.

Nor does Browning deploy totally or always obviously a dramatic mode. Many of the poems in this publication are presented as if in the traditions of expressive lyricism. But the overwhelming effect everywhere is of a poet dedicated to ambiguities—of tone, mood, point of view, image, conclusiveness—and readers are as much made aware of ironies or disjunctions in speakers’ perspectives as invited to share their feelings. As a poet seriously interested in music, Browning’s own poetry in these volumes might be characterized as a sustained exercise in modal ambiguity, where key signatures are unclear and harmonic relationships are shifting and uncertain. Such uncertainties do not make for easy reading, but may seem rather like listening to a fugue by Master Hugues, as it “broadens and thickens / Greatens and deepens and lengthens” (96-97). Readers might well ask Robert Browning, as the organist asks Master Hugues, whether they are always to confront such a world of unresolved complexity:

Such a web, simple and subtle,

Weave we on earth here in impotent strife,

Backward and forward each throwing his shuttle,

Death ending all with a knife? (107-10)

Such an endlessly contending world would be inimical to expressive pleasure or atemporal transcendence: no wonder readers were puzzled. But uncertain tones are partly the point of the exercise and readers’ expectations needed to shift from lyrical transcendence to dialectical drama.

The longer poems that formed the core group of what became known some time later as dramatic monologues (Slinn, “Monologue”) have always reasonably obviously dramatized distinctive selves: persons whose characteristics are defined by their speech, images, and narrative details. In those poems speakers are more self-conscious, often aware, like Cleon or Blougram, of the possibility of irony or fabrication. But the dramatic elements in more lyrical pieces have not always been so clear. Earlier readers sought lines or extracts that might identify the poet’s belief system—“Love is best” or “The instant made eternity”—although critics in the twentieth century came to realize that the lyrics are generally less than straightforward and need to be read also as voices other than the poet’s (Shaw, Temper; Slinn, Fictions; Ryals; Armstrong). The opening poem, for example, “Love Among the Ruins,” is an apparently simple love lyric celebrating the virtues of immediate pleasure. Yet, as the speaker anticipates a tryst amidst the landscape of a lost civilisation, the asymmetrical alternation of long and short lines with their rhythmical imbalance should alert readers to the possibility of asymmetrical values. The speaker celebrates the anticipated pleasure of his imminent meeting as superior to the emptiness of lost fame, but is the silent lover who will focus all on him (as he imagines her) really equal to the magnificence of the early empire with its “brazen” pillars and “thousand chariots” of gold? Is the love that he praises rather flat and lifeless, “the love of being, not of becoming” (Ryals 115)? Several of the love lyrics hover thus around the potential delusions and persuasions accompanying desire and its imminent gratification. In “Evelyn Hope,” what begins as a lament for the dead sixteen-year-old Evelyn quickly turns into the self-absorbed fantasy of an aging speaker (“thrice as old”) who, never known by her, imagines a future life when he will claim her as his own. In its simple lyrical manner, this poem dramatizes a classic narcissism that absorbs the desired other as its universal right, a right sustained and approved, the speaker claims, by God, who “creates the love to reward the love” (27). “The Last Ride Together” celebrates again the value of the immediate moment, fixing on present pleasures when the speaker still rides with his beloved, but the ride is their last because she has rejected him, making the prospect of the moment becoming eternal another fantasy of desired permanence. “Love in a Life” and “Life in a Love” celebrate the fundamental elusiveness of a lover’s presence, and “Two in the Campagna” is more about the impossibility of fusion between lovers than the delights of their meeting: “Only I discern— / Infinite passion, and the pain / Of finite hearts that yearn” (58-60). These are works therefore about the ambiguities as much as the attainments of personal sublimity. Pure lyricism (the expressive, atemporal purity of inner voice) in this collection is almost invariably disrupted: sometimes by ambiguities of tone, sometimes by ironies of perspective, sometimes (notably in the longer monologues) by the mimetic detail of narrative elements, and sometimes by the sheer capacity of the individual imagination for self-deception.

As might be expected, some readers objected that many of the poems were not really poetry. Trained to expect mellifluous language and regular rhythms from their poets, these readers were unprepared, it seems, for the often dissonant, asymmetrical verse of Browning’s speakers. But if poetry is language that draws attention to itself as language, that is exactly what Men and Women features—the acts and processes of speech in action. Too often readers have looked only for paraphrasable content, an extractable summary that would contain the work’s meaning. Content undoubtedly contributes to poetic meaning, but Robert Browning was also interested in language itself, in how language functions as a means of generating perception and understanding. Direct references to the role of language are more obvious in later volumes, particularly The Ring and the Book, but the signs of linguistic action are nevertheless already endemic in Men and Women, whose theme is “the making of meaning, the give-and-take of signification” (Tucker, Beginnings 185). A key to Browning’s poetic achievement therefore is invariably found in his display of verbal action, in how his poems dramatize the very processes of human discourse, of speakers struggling to articulate their world of interpersonal (and personal) affairs. Browning does not expect readers simply to admire tonal and expressive qualities in the manner of Mill’s overheard lyricism, but actively to engage with the problematic nature of his texts, on the dramatic level of metaphysical conceptualizing as well as on the technical level of syntax and diction. For many years this meant readers trying to decide whether speakers were to be admired or admonished. Is Bishop Blougram, for example, a clever and subtle cleric, a brilliant Catholic apologist in a sceptical age, or an opportunistic dilettante, more concerned with his private comforts than with the dynamics of Christian belief? Is the Grammarian a persistent and devoted scholar heroically pursuing a mastery of Greek language or some dogged introvert wasting his life on trivialities? Attention thus on judging speakers’ arguments allowed them to be treated as cases of special pleading—that is, not as poems at all, but as rhetorical explorations of belief and doubt, or values and choices. Then “character” was added to rhetoric, such that Browning, in the figure again of Blougram, “dethrones a saint in order to humanise a scoundrel” (Chesterton 189), and this move led to concentration on Browning’s portrayal of subjectivity (Langbaum; King; Shaw, Temper; Drew). Readers still debated the morality of speakers, but fundamentally Men and Women was seen to offer nineteenth-century dramas of individual selves, with their articulation of hopes and fears, justifications and fancies. Eventually, critics looked more closely at textual activity, at why poems that seem to urge moral evaluation of their speakers also seem to prevent univocal readings. This development occurred in a context when intellectual historians were beginning to examine the assumptions underpinning Romantic lyricism (Hosek and Parker) and to recognize that the supposedly pure voice (or cogito) in lyrical verse was a discursive effect generated by the expectations of idealist practices. Within this context, readers began to examine the greater totality of a poet’s linguistic art, and Men and Women then became a mid-nineteenth-century focal point for the poetic dramatization of discursive action. The human drama remains, but it is inseparable from its linguistic articulation: Browning’s men and women are speech acts, grounded in psychological and cultural origins (Tucker, Beginnings; Slinn, Fictions; Martin; Faas; Ryals; Armstrong).

Many twentieth-century critics had a problem with Men and Women, particularly the expanded monologues, since they rarely conformed to the discrete requirements of New Critical aesthetics—the poem as icon, neatly structured as a complete and fixed object, defined by its spatial form and with all parts cohering within an organic whole. But Browning’s developing art in 1855 is more attuned to Hegelian bacchanalia than to painting or organic metaphors of unity: it is a poetry of process, of speech in action, of form as movement where music is the aesthetic paradigm rather than painting, where the poetic art is to capture the momentary articulation of a reflection, or anxiety, or fragment of human narrative. Poetic formalism remains in terms of traditional devices of rhythm and sound, but form as the shape of articulated contemplation emerges from his growing emphasis, against contemporary expectations of poetry as a private art, on human expression as a social action. Hence many speakers are caught engaging with a social scene—talking to a journalist, explaining a dalliance with “sportive ladies” to the local police, persuading a wife to tarry a while before she meets her “cousin,” addressing a correspondent or a lover, assuming the audience of an interested friend, or imagining what they might say if their partner returned after a spat or were beside their fireside in life’s autumn. The articulations emerging from these engagements portray the politics of feeling and argument, and because such momentary acts are inseparable from a passing temporality, they are rarely concluded and rarely lead therefore to a fixed formalised object like a well-wrought urn. New Critical expectations of poetic formalism may well miss the subtleties of verbal process that lie at the heart of Browning’s texts.

If Cartesian or Romantic idealism fostered a dualism that separated the self from its social and political world, Browning’s portrayal of his men and women, voices not his own, challenged that dualism by showing how selves are part of open systems, inevitably integrated with social processes and other selves rather than isolated among mountains and nightingales. In these volumes individuals, notwithstanding that they speak in monologues, exist and speak in relation to social contexts, as part of human history therefore, rather than as atemporal, isolated minds, and that display is part of what makes the publication a significant event in the history of literature and cultural representation. Instead of allowing Mill’s model of overheard lyricism to explain poetry, Browning in Men and Women restores poetry to the realm of cultural construction and social interaction (see also Tucker, “Monologue”). These are volumes where the claims of personal utterance are indissolubly linked with the constructions and persuasions or anxieties and anticipations of, in shorter poems, passing consciousness, and, in longer poems, the grander designs of identity and power.

HOW TO CITE THIS BRANCH ENTRY (MLA format)

published March 2012

Slinn, E. Warwick. “On Robert Browning’s Men and Women.” BRANCH: Britain, Representation and Nineteenth-Century History. Ed. Dino Franco Felluga. Extension of Romanticism and Victorianism on the Net. Web. [Here, add your last date of access to BRANCH].

WORKS CITED

Armstrong, Isobel. Victorian Poetry: Poetry, Poetics, and Politics. London: Routledge, 1993. Print.

Browning, Robert. The Poems. Vol. 1. Eds. John Pettigrew and Thomas J. Collins. Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1981. Print.

Chesterton, G. K. Robert Browning. 1903. London: Macmillan, 1957. Print.

DeVane, William Clyde. A Browning Handbook. 2nd ed. New York: Appleton-Century-Crofts, 1955. Print.

Drew, Philip. The Poetry of Browning: A Critical Introduction. London: Methuen, 1970. Print.

Eagleton, Terry. How to Read a Poem. Oxford: Blackwell, 2007. Print.

Faas, Ekbert. Retreat into the Mind: Victorian Poetry and the Rise of Psychiatry. Princeton: Princeton UP, 1988. Print.

Hosek, Chaviva, and Patricia Parker, eds. Lyric Poetry: Beyond New Criticism. Ithaca: Cornell UP, 1985. Print.

Keats, John. “Ode on a Grecian Urn.” The Poetical Works of John Keats. Ed. H.W.Garrod. London: Oxford UP, 1956. 209-10. Print.

Kennedy, Richard S., and Donald S. Hair. The Dramatic Imagination of Robert Browning: A Literary Life. Columbia: U of Missouri P, 2007. Print.

King, Roma A., Jr. The Bow and the Lyre: The Art of Robert Browning. 1957. Ann Arbor: U of Michigan P, 1964. Print.

Langbaum, Robert. The Poetry of Experience: The Dramatic Monologue in Modern Literary Tradition. New York: Random House, 1957. Print.

Martin, Loy D. Browning’s Dramatic Monologues and the Post-Romantic Subject. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins UP, 1985. Print.

Ryals, Clyde de L. The Life of Robert Browning: A Critical Biography. Oxford: Blackwell, 1993. Print.

Shaw, W. David. The Dialectical Temper: The Rhetorical Art of Robert Browning. Ithaca: Cornell UP, 1968. Print.

—. The Lucid Veil: Poetic Truth in the Victorian Age. London: Athlone, 1987. Print.

Slinn, E. Warwick. Browning and the Fictions of Identity. London: Macmillan, 1982. Print.

—. “Dramatic Monologue.” A Companion to Victorian Poetry. Eds. Richard Cronin, Alison Chapman and Antony H. Harrison. Oxford: Blackwell, 2002. 80-98. Print.

Tucker, Herbert F., Jr. Browning’s Beginnings: The Art of Disclosure. Minneapolis: U of Minnesota P, 1980. Print.

—. “Dramatic Monologue and the Overhearing of Lyric.” Hosek and Parker. 226-43. Rpt. Critical Essays on Robert Browning. Ed. Mary Ellis Gibson. New York: G.K.Hall, 1992. 21-36. Print.