Abstract

These three paintings representing the decline of a family as the result of the wife’s presumed infidelity cannot be read in strictly linear fashion, as if they followed the narrative structure of serial fiction. Rather, a reading of the painting that takes into account the spatial and iconographic relationship between the three panels yields the complex and open-ended meaning of the triptych’s story.

In 1858, the realist painter Augustus Egg (1816-1863) exhibited a group of three paintings at the ![]() Royal Academy. They were untitled, all of the same size, and hung side by side as a unit. The meaning of these pictures, though not hinged together as in the case of Medieval or Renaissance triptychs, depends on their spatial arrangements and connections to one another.[1] Egg’s triptych tells the story of a family’s disintegration as the result of the wife’s presumed transgression and has become a telling cultural artifact for thinking about Victorian gender codes and morality. Because of the narrative character of this triptych and of Victorian realist painting generally, we often think of Egg’s trio of images in serial form or, in the words of Lynda Nead, as the “pictorial equivalent of a three-decker novel” (72). With special attention to the spatial, iconographic, and thematic relationships between the paintings, we can understand the story they tell as non-linear and multivalent, not a narrative that replicates the shape of the Victorian novel but one that depends on a distinct temporality and its attendant metaphysical meanings.[2]

Royal Academy. They were untitled, all of the same size, and hung side by side as a unit. The meaning of these pictures, though not hinged together as in the case of Medieval or Renaissance triptychs, depends on their spatial arrangements and connections to one another.[1] Egg’s triptych tells the story of a family’s disintegration as the result of the wife’s presumed transgression and has become a telling cultural artifact for thinking about Victorian gender codes and morality. Because of the narrative character of this triptych and of Victorian realist painting generally, we often think of Egg’s trio of images in serial form or, in the words of Lynda Nead, as the “pictorial equivalent of a three-decker novel” (72). With special attention to the spatial, iconographic, and thematic relationships between the paintings, we can understand the story they tell as non-linear and multivalent, not a narrative that replicates the shape of the Victorian novel but one that depends on a distinct temporality and its attendant metaphysical meanings.[2]

In the early years of his career, Egg specialized in paintings taken from Italian subjects and literary scenes, then added historical subjects to his repertoire and finally, like a number of other realist painters, turned to contemporary topics (Sandby 310; Treuherz, “Brief Survey” 19). He was a member of Dickens’ circle, acted in and designed sets for some of his plays, and traveled with him and Wilkie Collins to ![]() Italy and

Italy and ![]() Switzerland in 1853, after Dickens completed Bleak House and some few years before Egg exhibited his triptych (Forster 2: 94ff; Virag 147). While in Italy, he marveled at and copied works of art, especially at

Switzerland in 1853, after Dickens completed Bleak House and some few years before Egg exhibited his triptych (Forster 2: 94ff; Virag 147). While in Italy, he marveled at and copied works of art, especially at ![]() St. Peters in Rome, where he painted every day (Forster 2: 99). As a young man, he formed a sketching group with W. P. Frith and Richard Dadd. He supported the endeavors of the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood and had much in common with one of its founders, William Holman Hunt, whose 1853-54 painting, The Awakening Conscience (Fig. 1), is often identified as an important influence on his triptych (Virag 147).

St. Peters in Rome, where he painted every day (Forster 2: 99). As a young man, he formed a sketching group with W. P. Frith and Richard Dadd. He supported the endeavors of the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood and had much in common with one of its founders, William Holman Hunt, whose 1853-54 painting, The Awakening Conscience (Fig. 1), is often identified as an important influence on his triptych (Virag 147).

Figure 1: William Holman Hunt, The Awakening Conscience, 1853 (used with permission of the Tate Gallery. © Tate, London 2012)

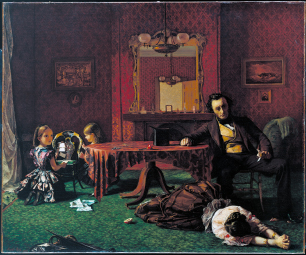

The subject of Egg’s trio of paintings was not only contemporary but also highly topical and controversial: the danger to middle-class life of infidelity—especially a wife’s—and the rapidity with which respectability could turn to ruin as a result. The central, most detailed, and most vividly colored panel (Fig. 2) depicts a bourgeois sitting-room with the wife prostrate, face down, on the floor, hands clasped as if in supplication, and angled to the right bottom corner of the frame. Her husband sits at a table on the right, just above her, with a crumpled, presumably revelatory note in his hand and a somber, almost dazed look on his face. To the left, the couple’s young daughters play at building a house of cards on a chair. Like Holman Hunt, Egg fills his painting with telling, symbolic iconography: a split apple to suggest the temptations of Eden and the weakness of Eve; a novel by Balzac at the base of the girls’ house of cards that gestures toward the insidious influences of French culture; four small paintings on the wall, one of the expulsion of Adam and Eve from paradise that hangs over the wife’s portrait, and one of a shipwreck that hangs over the husband’s (Helmreich 106-07). A mirror hangs at the back of the room and reflects a chandelier and doorway, which the figures in the room face.[3]

Figure 2: Augustus Egg, Past and Present, no.1, 1858 (used with permission of the Tate Gallery. © Tate, London 2012)

The two other panels, rendered in an identical style, are dark and almost monochromatic by contrast. In one (Fig. 3), the two daughters, now grown, one dressed in white and one in black, sit in a sparsely furnished, largely undecorated room, whose colorlessness accentuates the difference between the sisters’ reduced circumstances and the bourgeois comfort of their earlier life. One young woman kneels and places her head on her sister’s lap; the other gazes out the window at the city’s skyline and a partly obscured moon. The portraits of the girls’ parents hanging on the sitting-room walls in the more vividly colored panel appear here, on either side of the window.

In the second visually subdued panel (Fig. 4), a woman—presumably the wife—huddles on the left of the frame, pictured beneath an arch by the ![]() Thames, holding a small child of indeterminate age whose face and body, save its feet, are covered with the woman’s shawl. A wrecked wooden boat, echoing the painting of a shipwreck in the drawing room panel, lies next to her, and a pile of rocks sits at the right of the frame. A number of posters are plastered on the wall of the arch above her head. Three of them advertise plays with suggestive titles—Victims, A Cure for Love, and Return the Bride—and another touts cheap fares to

Thames, holding a small child of indeterminate age whose face and body, save its feet, are covered with the woman’s shawl. A wrecked wooden boat, echoing the painting of a shipwreck in the drawing room panel, lies next to her, and a pile of rocks sits at the right of the frame. A number of posters are plastered on the wall of the arch above her head. Three of them advertise plays with suggestive titles—Victims, A Cure for Love, and Return the Bride—and another touts cheap fares to ![]() Paris, a city whose dubious moral status we already understand from the Balzac novel in the drawing-room scene (Rutherford). The woman looks out at the river. The same partly obscured moon at which her daughter gazes in the other panel sheds light on the water from the top right corner. A small gaslight hangs at the top of the arch. Its glass shade is broken, but its light twinkles alongside the moon.

Paris, a city whose dubious moral status we already understand from the Balzac novel in the drawing-room scene (Rutherford). The woman looks out at the river. The same partly obscured moon at which her daughter gazes in the other panel sheds light on the water from the top right corner. A small gaslight hangs at the top of the arch. Its glass shade is broken, but its light twinkles alongside the moon.

Figure 3: Augustus Egg, Past and Present, no. 3, 1858 (used with permission of the Tate Gallery. © Tate, London 2012)

Figure 4: Augustus Egg, Past and Present, no. 2, 1858 (used with permission of the Tate Gallery. © Tate, London 2012)

Egg’s triptych came to be known as Past and Present. No one knows who invented the title, but the work was listed this way in a Christie’s catalogue as early as 1861 (Edelstein 208). Originally, the triptych was simply accompanied by a gloss of Egg’s composition that reads like a diary entry or letter: “August the 4th. Have just heard that B_____ has been dead more than a fortnight, so his poor children have now lost both parents. I hear she was seen on Friday last near ![]() the Strand, evidently without a place to lay her head. What a fall hers has been!” This text emphasizes, in the first instance, the fate of the father and refers to the mother simply as “she.” The gloss adds a novelistic note and has prompted both a narrative reading of the paintings and a particular sense of their ordering. Scholars often refer to the panel picturing the wife’s reduced, outcast state, mentioned last in the gloss, as the third or final painting and identify it as “Past and Present #3,” as if it concludes the story of the family’s fall and belongs on the far right of the three pictures, with the daughters first, on the left, and the drawing room in the middle (Nochlin 64; “Augustus Leopold Egg”).[4] Instinctively drawn to reading the paintings as a progression or unfolding story with a didactic message, scholars have also cited Hogarth’s moralizing series of paintings as an influence.[5] In this version of the narrative, a destitute and outcast woman beneath the Adelphi arches marks the end to a downward family trajectory.

the Strand, evidently without a place to lay her head. What a fall hers has been!” This text emphasizes, in the first instance, the fate of the father and refers to the mother simply as “she.” The gloss adds a novelistic note and has prompted both a narrative reading of the paintings and a particular sense of their ordering. Scholars often refer to the panel picturing the wife’s reduced, outcast state, mentioned last in the gloss, as the third or final painting and identify it as “Past and Present #3,” as if it concludes the story of the family’s fall and belongs on the far right of the three pictures, with the daughters first, on the left, and the drawing room in the middle (Nochlin 64; “Augustus Leopold Egg”).[4] Instinctively drawn to reading the paintings as a progression or unfolding story with a didactic message, scholars have also cited Hogarth’s moralizing series of paintings as an influence.[5] In this version of the narrative, a destitute and outcast woman beneath the Adelphi arches marks the end to a downward family trajectory.

The iconography of the two monochromatic or side paintings, however, seems to suggest that the mother beneath the arch would be placed first, on the extreme left, and the panel representing the two orphaned daughters last, on the right. And according to nineteenth-century accounts, this seems to be the order in which they were originally placed.[6] Writing in 1860 in the Gazette des Beaux-Arts about a ![]() Brussels exhibition of the Egg paintings, W. Bürger writes, “Dans le compartiment de droite, un galetas misérable avec une femme qui pleure ou qui blasphème. Dans le compartiment de gauche, les sombres arcades d’un pont de la Tamise” (94).[7] In a 1983 article, T. J. Edelstein asserts that Bürger describes the order in which the paintings were originally hung. Further, she remarks that the Tate Gallery had replicated this order, at least at the time of the publication of her article: “drawing-room scene in the centre, the bridge scene to the left and the bedroom scene to the right” (205).

Brussels exhibition of the Egg paintings, W. Bürger writes, “Dans le compartiment de droite, un galetas misérable avec une femme qui pleure ou qui blasphème. Dans le compartiment de gauche, les sombres arcades d’un pont de la Tamise” (94).[7] In a 1983 article, T. J. Edelstein asserts that Bürger describes the order in which the paintings were originally hung. Further, she remarks that the Tate Gallery had replicated this order, at least at the time of the publication of her article: “drawing-room scene in the centre, the bridge scene to the left and the bedroom scene to the right” (205).

Nonetheless, this language of temporality—first, last, third, final—fails to capture the particular temporal schema Egg offers here. Clearly, the two wings of the triptych represent simultaneous scenes that take place an unspecified number of years after the moment of the central panel. The mother in one panel and her two grown daughters in the other gaze at the very same moon: the mother gazes from the left, the daughters from the right, placing the moon in the center, as it were. It seems important to consider, as well, that Egg’s gloss takes the form of one unknown person’s account, the recordings of one observer of the family’s saga, and not a definitive, omniscient description of events. Is this diarist or correspondent a sympathetic witness? A malicious gossip? A conventional Victorian moralist whose sympathies lie with the deceased father? We do not know, and the cryptic labeling of the triptych contributes to the ambiguities and possible variations of its meanings.

Contemporary critics commented, sometimes impatiently, on the perplexing temporality of the paintings. A number of them understood that the two wings were or might be contemporaneous (Art Journal 168); still other critics were confused by them or suggested that they should have been placed side by side beneath the middle picture (Athenaeum 566). The Times review complained about the general illegibility of the triptych: it was “not easy to read,” and “unraveling the meaning of the sad story” proved difficult (9). The Athenaeum critic regretted that the story of the paintings “is not quite clear, indisputable, and transparent,” ventured that the husband might have been a “drunken gamester” who threw his wife to the floor in a quarrel, and objected that the small child in the Adelphi arch scene is introduced “confusedly” (566). Many of these critics also reviewed W. P. Frith’s Derby Day, which was exhibited concurrently with the triptych (fig. 5). They vastly preferred the massive and ebullient realist panorama to Egg’s painful story, though it’s likely that reading Derby Day, with its multiplicity of small scenes and huge cast of characters, would not have been an easy matter either (Athenaeum 565; Times 9; Sharpe’s London Magazine 333). Frith’s crowded panorama presents different problems of legibility than does Egg’s triptych but offers another reminder that visual narrative in realist painting and literary narrative in Victorian fiction require different strategies of reading.

Figure 5: William Powell Frith, Derby Day, 1856-8 (used with permission of the Tate Gallery. © Tate, London 2012)

Aside from complaints about its illegibility, the triptych also elicited serious reservations about the suitability of Egg’s subject matter. “Although the domestic wreck illustrated in these pictures . . . may be in real life a daily occurrence,” The Art Journal commentator declared, “it is a subject too poignant for a series of paintings” (167). The Athenaeum review was even more emphatic in its disapproval: Egg had crossed the line, offering “horrors that should not be painted for public and innocent sight again” (566). The triptych was painted, it continued, “with an unhealthy determination to dissect” the chilling events it depicted. The “Fine Arts” column in Sharpe’s London Magazine concurred. Though terrible, the story of the triptych rang true: “but should it ever have been painted? Who can put that in a gallery, for honest women to look at?” (Sharpe’s 333). Frith’s Derby Day attracted huge numbers of visitors, requiring a railing and policeman to contain the crowds, while Egg’s triptych, with a less conventional structure and more demanding and disquieting subject, remained unsold in the artist’s studio at the time of his death (Treuherz, Victorian Painting 106, 114). Julian Treuherz suggests that Egg’s paintings challenged “orthodox assumptions” not by telling a story of transgression but by “showing sympathy for the woman” (114).

Over the last few decades, scholars have offered a number of incisive and compelling analyses of these paintings. Early on, the pioneering feminist art historian Linda Nochlin emphasized the paintings’ expression of the need to expel the erring wife from the “paradise” of the parlor and consign her to the outside, the city, the space of the fallen woman (1978). Following suit, Lynda Nead read the narrative of the paintings as a moral tale, warning of the fundamentally tainted and contaminating nature of female sexuality (1988). T. J. Edelstein, writing between Nochlin and Nead, suggested that Egg’s work comments on the social effects of adultery and laws involving divorce and child custody (1983). More recently, Annabel Rutherford, pointing to the theatrical structure of the three paintings, moves away from a view of the works as didactic and sees them instead as a “protest against the folly of Victorian marriage” (2). Though Edelstein and Rutherford see Eggs’ paintings as an indictment not of the wife-as-fallen-woman but rather of law and social convention, Treuherz seems alone in seeing the triptych as especially generous to the wandering wife. Though he does not elaborate on his reasons for asserting the paintings’ “sympathy for the woman,” it seems clear that only by reading the structure of the three paintings carefully can viewers reach such a conclusion (Treuherz 114).

The two wings of the triptych depict the same moment in time and share the image of the moon, with an unmistakable, single flat cloud floating beneath it in both pictures, and thereby seem to commune with each other across—or over—the central image of the humiliating discovery of the wife’s transgression. The two panels communicate in a way that parallels and reinforces the implicit connection between mother and daughters that is signaled by their common and simultaneous gazing at the moon. Though the central panel separates the women in the family and though they are dispersed to different parts of the city, this communion suggests that what literally and figuratively comes between them has not, indeed, fully divided them. We know from the gloss that the father has died, and we also know that the mother has not, at least not yet. The iconography associated with fallen women in the period might lead viewers to expect that the woman’s next step will be suicide, that she will hurl herself into the Thames like the “unfortunate” of Thomas Hood’s “The Bridge of Sighs” (1844) or the woman whose body has been washed up or dredged from the Thames in G. F. Watt’s painting, Found Drowned (1848-50). That this possibility exists is undeniable, but the story, it should be emphasized, is not over. In the “present,” at least, these three women are still alive, still tied to one another not only by ruin but also by enduring feelings of grief and longing. And it may very well be that the daughters come “last” or—farthest to the right—in the original arrangement, not the outcast mother. If we are to read the narrative from left to right, then, the daughters constitute its end and perhaps its future.

The wings also possess a spiritual and even overtly Christian aspect, which they share with Hood’s, Watts’, and even Holman Hunt’s depictions of ruined women. The women in Egg’s two side paintings look at the moon in a wishful and imploring way that suggests prayer. In Egg’s painting “The Night before Naseby,” exhibited the year after his triptych, a young Cromwell, the rebellious Puritan, kneels in his tent on the night before battle with hands clasped and looks skyward (Fig. 6). Above him and slightly to the left, a moon shines, partly obscured by a tree branch. This painting associates night prayer with the radiant moon, a repetition of the motif of the triptych, and it does so in the portrayal of a presumably heroic figure.

The mother’s night picture includes not only the moon but also the gas light at the top of the arch. Its glass shade broken, it nonetheless provides a flicker of light, rendered as a kind of star. A similar twinkling light hovers over the female corpse laid out under an arch with the cityscape behind her in Watts’ Found Drowned (fig. 7).[8] Egg’s crouched woman, pressed against the wall of the arch and looking upward, holds a small child, perhaps dead, perhaps asleep. The painting’s hint of Madonna and child, combined with the light that mimics the Morning Star, offers the possibility of this mother’s holiness—or at least of her redemption. Hood’s entire poem implores the reader to see his fallen woman as forgivable, blessed, and redeemable. “Cross her hands, humbly,” Hood’s speaker directs us, “As if praying dumbly, / Over her breast” (ll 63-65). In the Awakening Conscience, Holman Hunt depicts a kept woman’s moment of spiritual revelation. She rises suddenly from her lover’s lap and looks, literally and figuratively, toward the light.

Figure 6: Augustus Egg, The Night Before Naseby, 1859 (used with permission of the Royal Academy of Arts, London. © Royal Academy of Arts, London/ John Hammond)

Figure 7: George Frederick Watts, Found Drowned, 1848-50 (used with permission of the Watts Gallery)

One other disgraced and partially forgiven woman needs to be mentioned here, and that is Lady Dedlock, the mother of an illegitimate child—a daughter—in hiding from her past, whose story Dickens had completed shortly before his trip to the Continent with Egg in 1853. In chapter 57 of the novel, Inspector Bucket and Esther Summerson go in search of Esther’s mother, now at large in the London night. Moving through a “labyrinth of streets,” they come to a waterside neighborhood and “a little slimy turning” that the wind from the river “did not purify” (827). Esther, narrating, sees a crowd gathered around a bill posted on the “mouldering wall” that reads “FOUND DROWNED.” Bucket descends from the carriage while Esther sits suffering, fearing the worst. In prose that alludes to but never spells out the understood trajectory of the fallen woman, Esther describes Bucket’s conversation with a muddied, sodden man and their contemplation of “something secret.” Wiping his hands on his coat, Bucket returns, signaling that the “something wet” he had touched—a corpse or article of clothing perhaps—was not Lady Dedlock’s (827). Not drowned and not precisely a suicide, though soon discovered to be dead, Esther’s mother had already been partly released from guilt before this scene commences. The novel punishes Lady Dedlock by banishing her and, indeed, killing her off, but it also allows her some redemption in the reunion with her forgiving and accepting daughter earlier in the novel. Dickens works through the problem of a disgraced mother’s complicated effect on the moral status and fate of a daughter, and Egg seems to be engaged with a similar social and narrative question. Whether Egg knew Bleak House we do not know, but we can surmise that his compassionate disposition toward the figure of the ruined woman was close to Dickens’, as well as to Hood’s and Watts’. And it is also possible that he took the scene of the London waterside from Dickens’ novel as well as from these other literary and visual precursors.

The two side panels of Egg’s triptych, alike in size and exhibited next to the central panel, tell a story of fall and misery but, in conversation with each other, also gesture toward grace and hope. They offer a counter-narrative to the central story of familial disgrace and alienation. In the middle panel, no two members of the family look at each another. The husband stares out beyond the frame towards us, the smaller child, oblivious, looks at her structure of cards, the other daughter looks in alarm at the prostrate mother, and the mother lies head on arm, her face fully hidden. There is greater communion between the figures in exile from home than in this image of the still intact family. But the point here is that these paintings demand to be read as a triptych, the three panels viewed and taken in simultaneously. Like medieval and early modern triptychs, which Egg would have seen in abundance in Italy, this one has no single narrative. A multiplicity of stories and meanings floats among the three panels. The uncertain order of their placement, both originally and ever since, suggests that we look beyond the possibility of a conclusive serial narrative and search for meanings that defy linear progression and earthly resolution. As is the case with a number of the other realist paintings mentioned here—the Awakening Conscience among them—the viewer is called upon to piece together and interpret a narrative of modern life.

published June 2013

HOW TO CITE THIS BRANCH ENTRY (MLA format)

Nord, Deborah Epstein. “On Augustus Egg’s Triptych, May 1858.” BRANCH: Britain, Representation and Nineteenth-Century History. Ed. Dino Franco Felluga. Extension of Romanticism and Victorianism on the Net. Web. [Here, add your last date of access to BRANCH].

WORKS CITED

“Augustus Leopold Egg.” Tate. Tate, 2013. Web. 15 August 2012.

Bürger, W. “Exposition des Beaux-Arts à Bruxelles.” Gazette des Beaux-Arts VIII (1860): 94-95. Print.

Corbett, David Peters. The World in Paint: Modern Art and Visuality in England, 1848-1914. University Park: Pennsylvania State UP, 2004. Print.

Dickens, Charles. Bleak House. London: Penguin, 1985. Print.

Edelstein, T. J. “Augustus Egg’s Triptych: A Narrative of Victorian Adultery.” Burlington Magazine 125.961 Apr. 1983: 202-12. Print.

“Exhibition of the Royal Academy.” Times 22 May 1858: 9. Print.

“Fine Arts.” Sharpe’s London Magazine XII 31 May 1858: 331-33. Print.

Flint, Kate. The Victorians and the Visual Imagination. Cambridge: Cambridge UP, 2000. Print.

Forster, John. The Life of Charles Dickens. 2 vols. London: Chapman and Hall, n.d. Print.

Helmreich, Anne. “Augustus Leopold Egg, Past and Present.” The Victorians: British Painting 1837-1901. Ed. Malcolm Warner. New York: Abrams, 1996. 106-07. Print.

Hood, Thomas. “The Bridge of Sighs.” The Victorians: An Anthology of Poetry and Poetics. Ed. Valentine Cunningham. Oxford: Blackwell, 2000. 65. Print.

Jacobs, Lynn. “Rubens and the Northern Past: The Michielsen Triptych and the Thresholds of Modernity.” Art Bulletin 91.3 (2009): 302-24. Print.

Nead, Lynda. Myths of Sexuality: Representations of Women in Victorian Britain. Oxford: Blackwell, 1988. Print.

Nochlin, Linda. “Lost and Found: Once More the Fallen Woman.” Women, Art, and Power and Other Essays. Boulder: Westview, 1988. Print.

“Royal Academy.” Art Journal IV (June 1858): 167-68. Print.

“Royal Academy.” Athenaeum 1592 (1 May 1858): 565-67. Print.

Rutherford, Annabel. “A Dramatic Reading of Augustus Leopold Egg’s Untitled Triptych.” Tate Papers 7 (Spring 2007): n. pag. Web. 31 Jan. 2012.

Sandby, William. The History of the Royal Academy of Arts. London: Longmans, 1862. Print.

Treuherz, Julian. “A Brief Survey of Victorian Painting.” Art in the Age of Queen Victoria. Ed. Helen Valentine. New Haven: Yale UP, 1999. 12-26. Print.

—. Victorian Painting. London: Thames, 1993. Print.

Virag, Rebecca. “Biographies.” Art in the Age of Queen Victoria. Ed. Helen Valentine. New Haven: Yale UP, 1999. 143-59. Print.

ENDNOTES

[1] By contrast, George Elgar Hicks’ trio of paintings, titled Woman’s Mission (1863), presents three consecutive, related images that do not constitute a dramatic narrative. See Treuherz, Victorian Painting 114.

[2] Egg’s paintings call for what Kate Flint describes as a “variant of narrative reading [that] assumes not so much that there is one definite story, and perhaps moral, to be disinterred from a painting’s visual evidence, but rather . . . that they are used as a starting point for speculating about possible aspects of the behaviour of the depicted characters” (220-21). See also David Peters Corbett, The World in Paint: Modern Art and Visuality in England, 1848-1914, especially chapter 1. Corbett has a relevant discussion of the ambiguous relationship between Dante Gabriel Rossetti’s painting The Girlhood of the Virgin (1848-49) and the two sonnets exhibited with the painting and ostensibly meant as a gloss (47-49). Corbett suggests that Pre-Raphaelite thinking about the “relative capacities of language and the visual” is worth examining in the context of what he calls Rossetti’s “alternative materiality” (42).

[3] Linda Nochlin points out that this setting triggers “ironic reminiscences of the Arnolfini Wedding Portrait” (63).

[4] Currently, the Tate Britain hangs the three panels in the following order: the drawing-room scene is on the left, the two daughters in the middle, and the outcast mother on the right. This arrangement, suggesting that the drawing-room scene is “Act I,” may be influenced by Annabel Rutherford’s article, now on the Tate website, arguing for a “dramatic reading” of the triptych.

[5] T. J. Edelstein suggests that Egg was also influenced by the convention of paired pictures, common in the late eighteenth century and the early nineteenth (205).

[6] Edelstein writes that Egg’s triptych “mimics not only the physical form of a medieval triptych but the temporal connotations as well. . . . Egg makes his side paintings exist in a separate time and space and yet comment on the action of the central scene” (205). For the temporal complexities of certain Renaissance triptychs, see Jacobs.

[7] “In the right compartment, a miserable garret with a woman who cries or blasphemes. In the left compartment, the dark arcades of a Thames bridge.”

[8] Watts did not exhibit the social-realist works, including Found Drowned, that he produced around 1850 until decades later, so it is very possible that Egg never saw this painting (Treuherz, Victorian Painting 39-40).