Abstract

Looking both backward and forward, E. Nesbit’s The Story of the Treasure Seekers stands at the intersection of Victorianism and modernism. The novel crosses borders in another sense as well: in its handling of references to advertising, newspapers, and iconic historical events, it highlights the extent to which fact and fiction, reportage and mythmaking, alike depend upon artifice. The publication of Nesbit’s breakthrough work, which foregrounds the importance of mass culture to middle-class children’s imaginations, marks a historical change in perceptions of children’s relationship to consumerism.

Figure 1: “The girls used to read aloud to Noel all day,” illustration by Frances Ewan to “The Nobleness of Oswald,” _Treasure Seekers_ (1899)

E. Nesbit’s The Story of the Treasure Seekers,[1] which appeared in volume form in 1899,[2] reflects a watershed in children’s culture, the recognition and even endorsement of childhood’s imbrication with mass media. Children had been the targets of advertising and product tie-ins since the emergence of a distinct children’s literature in the eighteenth century; John Newbery’s A Little Pretty Pocket-Book (1744) was sold with “a ball and pincushion[,] the Use of which will infallibly make Tommy a good Boy, and Polly a good Girl,” according to the announcement on the book’s title page. The explosive growth of children’s periodicals in the nineteenth century was enabled in part by advertisers’ recognition of a potentially lucrative market for their wares, and even magazines such as the Boy’s Own Paper, a periodical sponsored by the Religious Tract Society, came wrapped in covers advertising pesticides, camera equipment, baby food, magic tricks, collectibles, books, pens, ready-made clothing, and more.[3] Children were also often used in advertising rhetoric, a particularly famous instance being the repurposing of John Millais’s 1886 painting A Child’s World—later known as Bubbles—to sell Pears’ Soap. Where Nesbit’s text marks a departure from Victorian norms, however, is in its recognition and acceptance of advertising, journalism, and related forms of popular culture as part of the modern child’s cultural capital.

Consider, for instance, Figure 1 above, taken from the original serial publication of Treasure Seekers. This illustration might seem to involve a typical moment of Victorian sentimentality. The sick child, receiving the sympathetic attention of a loving sister, appears in many nineteenth-century texts, often as part of a domestic narrative with religious overtones and a focus on woman’s role as ministering angel; Charles Dickens’s Paul and Florence Dombey are well-known examples of the paradigm. Yet the image contains a clue that times have changed. The work from which Nesbit’s Alice Bastable is reading is not the Bible or another text associated with the reader’s improvement, but an illustrated periodical of a size and format usually associated with mass-market secular appeal. This choice on the illustrator’s part makes clever reference to the preoccupation of the novel’s central characters, twelve-year-old narrator Oswald Bastable and his four siblings, with the culture of consumerism and the adult marketplace.

The trope of the sick child in need of sisterly comfort is not the only Victorian convention that Nesbit both exploits and interrogates in this novel, the first of her works to achieve significant success. Using Oswald’s voice, she rejects a number of prescriptive attitudes toward childhood that readers may think of as characteristic of the nineteenth century. Oswald, who repeatedly expresses scorn for the morally and emotionally didactic purposes to which the mid-nineteenth century often put the idealized child, clearly sees himself as a modern boy, and, although he occasionally occupies the ethical high ground, he simultaneously expresses his discomfort with attempts to be virtuous. Yet simultaneously, Nesbit repeatedly makes use of the past in ways that, as critic Susan Anderson points out, prompt sentimental and nostalgic responses from many adult readers. In other words, one might say that Nesbit combines an outlook that emphasizes its difference from the mid-Victorian sensibility with an affect that at least occasionally seems eminently Victorian, so that Treasure Seekers’s relationship to its moment is complex. While the keynote of this novel is humor, it also employs stock nineteenth-century situations: over the course of the narrative, it adds to the trope of the sick child the tropes of the motherless child, the boy protecting his sister, and the children who by touching the heart of an adult transform their material circumstances.

These tropes are not always used in a spirit of parody. But despite Nesbit’s flirtations with earnestness, and unusually for fictional middle-class children of the era, what preoccupies the Bastable children in Treasure Seekers is money. It is noteworthy that they perennially get into trouble through their apparent inability to refrain from coopting adult privilege and property; in an era that sought to make ever firmer demarcations between the position of child and that of adult, what Nesbit often celebrates about the Bastables is their failure to know their proper generational place. I propose that this blurring of child and adult is particularly apparent in the Bastables’ immersion in a consumerist culture marked by a matching blurring of lines between marketing devices and reality, and that Nesbit’s willingness to acknowledge and accept this immersion on the children’s part reflects a significant shift in late-century perception. Treasure Seekers alludes to a wide range of popular-culture products, from advertisements to historical events to literary works of the nineteenth century and earlier. This allusiveness enables Nesbit to explore the extent to which the rhetoric of commodification – including the commodification of childhood – informs and shapes the imagination of her young middle-class subjects. Like the paradoxical combination of Oswald’s self-consciously un-Victorian rejection of sentiment and Nesbit’s occasional evoking of a sentimental response from the reader, Oswald’s many references to the cultural knowledge of his era suggest both a dependence on that knowledge and an up-to-the-minute refusal to treat culture solemnly. Somewhat paradoxically, the very frequency with which pre-existing texts are invoked suggests a lighter version of what a seminal modernist work, The Waste Land (1922), would later refer to as a “shor[ing] up” of “fragments,” an obsession with intertextuality that, the work of figures such as Lewis Carroll notwithstanding, is not widely characteristic of Victorian writing.

Advertising

Raymond Williams identifies the 1880s and 1890s as the foundation for the “fully developed ‘new advertising’ of the period between the [world] wars” (n.pag.). Not coincidentally, the 1890s also experienced protests about the omnipresence and aggressiveness of advertising. The Society for Checking the Abuses of Public Advertising (SCAPA) was founded in 1898 and succeeded in enacting some regulations on advertising venues and methods (Williams n.pag.), but the tide was with the advertising industry. Although the cult of domesticity rested in part on the belief that middle-class women and children who were not engaged in paid employment were less implicated than money-earners in the worship of Mammon, Nesbit’s novel makes clear that children, too, are very much creatures of the advertising economy. The Bastables’ interior landscape, she suggests, is dotted with billboards.

The relationship of the Bastable children to advertising is underscored when the children are introduced and Oswald notes of his youngest brother, “His real name is Horace Octavius, but we call him H.O. because of the advertisement, and it’s not so very long ago he was afraid to pass the hoarding where it says ‘Eat H.O.’ in big letters” (Nesbit 4). The reference is to a Hornby’s Oatmeal advertising campaign of the 1890s (originating in the U.S.; Sivulka 54); the line’s importance to Nesbit is clear from the fact that when the Bastable stories were published serially, the narration repeated it on multiple occasions as a way of orienting new readers. For instance, the version of “Being Detectives” published in May 1899 as the sixth installment of the narrative to appear in Pall Mall[4] begins, “If you have not read about us in this Magazine before, you will need to be told that . . . there is H. O., whose name is Horace Octavius, but we call him H. O., because of the advertisement, and he is never quite sure that people won’t take the advertisement’s advice and eat him. But I need not say we elder ones know better” (Nesbit 332n1). Thomas Richards remarks in his discussion of Victorian advertising that between the ![]() Great Exhibition of 1851 and the end of the century, newly sophisticated advertising turned the commodity into “the one subject of mass culture, the centerpiece of everyday life, the focal point of all representation, the dead center of the modern world” (1). It is Richards’s last clause to which I want to draw particular attention, as H.O.’s identity with Hornby’s Oatmeal seems above all to establish the extent to which the Bastables are products of their moment. H.O. may possess not one but two names whose original resonance is classical, but the Roman dignity of the references to the famous poet Horace and to Gaius Octavius (later the emperor Augustus) has been emphatically overlaid by the popular culture of the 1890s. As a turn-of-the-century child, H.O. is simultaneously emotionally affected by and potentially indistinguishable from the commodity, a consumer who may run the risk of being consumed by a commercial realm whose potency and geographical sweep rival or surpass those of imperial

Great Exhibition of 1851 and the end of the century, newly sophisticated advertising turned the commodity into “the one subject of mass culture, the centerpiece of everyday life, the focal point of all representation, the dead center of the modern world” (1). It is Richards’s last clause to which I want to draw particular attention, as H.O.’s identity with Hornby’s Oatmeal seems above all to establish the extent to which the Bastables are products of their moment. H.O. may possess not one but two names whose original resonance is classical, but the Roman dignity of the references to the famous poet Horace and to Gaius Octavius (later the emperor Augustus) has been emphatically overlaid by the popular culture of the 1890s. As a turn-of-the-century child, H.O. is simultaneously emotionally affected by and potentially indistinguishable from the commodity, a consumer who may run the risk of being consumed by a commercial realm whose potency and geographical sweep rival or surpass those of imperial ![]() Rome.

Rome.

Nesbit’s time-travel fantasies repeatedly make the point that the distant past had its own popular culture and should not be romanticized as uniformly glorious or highbrow; that is, the move from ancient Rome to late-Victorian London may be a move not from the sublime to the mundane but from one mundane setting to another. Similarly, the advertising references in Treasure Seekers insist upon the power of the mundane in the Bastables’ present-day world. For example, when Oswald and his brother Noël make an excursion to ![]() Fleet Street, they observe and reject two markers that might be considered references to the sublime. The first is the monument in

Fleet Street, they observe and reject two markers that might be considered references to the sublime. The first is the monument in ![]() St. Paul’s to the Victorian hero General Charles George Gordon, the second

St. Paul’s to the Victorian hero General Charles George Gordon, the second ![]() Smithfield, the execution site of the Smithfield Martyrs in the sixteenth century. The Gordon memorial “is very flat, considering what a man he was,” Oswald notes, and Smithfield is “rather dull,” since “they don’t burn people any more there now” (28). What impresses Oswald more favorably is the “jolly Bovril sign that comes off and on in different coloured lamps” (28). Critic Dennis Denisoff has pointed out that nineteenth-century cultural commentators understood children to be particularly susceptible to the blandishments of consumerism because of the presumed “plasticity” of their sensibilities (2). Treasure Seekers would seem to ratify this perception. At least from the point of view of the naïve child, advertising, particularly when yoked to modern technology, is the new art. In their appreciation of the wonders of the Bovril sign, the Bastables are implicitly positioned as opponents to the anti-advertising forces of SCAPA, who, Williams notes (n.pag.), had successfully lobbied for regulation of precisely this form of advertising. Nesbit, who was active in reform circles but whose children’s books sometimes take high-minded adults to task for being faddish and not much fun, seems unperturbed by Oswald’s pleasure in the sign.

Smithfield, the execution site of the Smithfield Martyrs in the sixteenth century. The Gordon memorial “is very flat, considering what a man he was,” Oswald notes, and Smithfield is “rather dull,” since “they don’t burn people any more there now” (28). What impresses Oswald more favorably is the “jolly Bovril sign that comes off and on in different coloured lamps” (28). Critic Dennis Denisoff has pointed out that nineteenth-century cultural commentators understood children to be particularly susceptible to the blandishments of consumerism because of the presumed “plasticity” of their sensibilities (2). Treasure Seekers would seem to ratify this perception. At least from the point of view of the naïve child, advertising, particularly when yoked to modern technology, is the new art. In their appreciation of the wonders of the Bovril sign, the Bastables are implicitly positioned as opponents to the anti-advertising forces of SCAPA, who, Williams notes (n.pag.), had successfully lobbied for regulation of precisely this form of advertising. Nesbit, who was active in reform circles but whose children’s books sometimes take high-minded adults to task for being faddish and not much fun, seems unperturbed by Oswald’s pleasure in the sign.

The effectiveness of advertising’s address to the unsophisticated reader also helps to drive the plot. Like Nesbit’s husband Hubert Bland, the Bastables’ father has failed in business because a partner has absconded with the funds of their joint venture. After the children vow to restore the family fortunes, Dicky, the second eldest boy, concludes that the obvious answer is to respond to one of the “advertisements in the papers, telling you that ladies and gentlemen can easily earn two pounds a week in their spare time, and to send two shillings for sample and instructions, carefully packed free from observation” (6). The garbled syntax of Dicky’s rendition, in which the instructions rather than the sample are carefully and discreetly packaged, highlights his uncritical susceptibility to a form of advertising that has today migrated to the Internet but that otherwise has not changed much over time.

The money-making method in question turns out to be selling sherry, which the children find difficult because they are too young to be successful hucksters of this particular product. Even so, they have absorbed the patter, as becomes clear from Alice’s approach to the butcher: “I want to call your attention to a sample of sherry wine I have here. It is called Castilian something or other, and at the price it is unequalled for flavour and bouquet” (77). Significantly, their comically doomed entrance into the wine business is not the first of their efforts to arise from a susceptibility to advertisements; earlier, Dicky has drawn his siblings’ attention to two other pitches. One claims, “£100 secures partnership in lucrative business for sale of useful patent. £10 weekly. No personal attendance necessary. Jobbins, 300, ![]() Old Street Road” (58), and the second (which they expect to be the source of the £100) is a come-on from a moneylender promising “cash from £20 to £10,000 on ladies’ or gentlemen’s note of hand alone, without security. No fees. No inquiries. Absolute privacy guaranteed” (59). Although the moneylender refuses to provide the desired loan to such youthful clients and warns them that the Jobbins advertisement is fraudulent, and, although experience has shown that Dora’s “face came all red and rough when she used the Rosabella soap that was advertised to make the darkest complexion fair as the lily” (88),[5] the children’s faith in advertising remains unshaken throughout the novel. What Nesbit invokes here is the power of the text, and specifically the commercial and overtly manipulative text, to shape its reader’s vision of the adult world. Fraudulent though these advertisements may be, their very power to mislead depends upon one’s willingness to take them at face value as reliable guides in decision-making, as the Bastables do. While the Bastables also consume texts whose primary audience is children, the importance of the advertisement aimed ostensibly at adults indicates that in the realm of reading, there is no separate and protected space for the young. Just as Nesbit’s work was serialized in periodicals bought primarily by adults, children are always already implicated in the marketplace.

Old Street Road” (58), and the second (which they expect to be the source of the £100) is a come-on from a moneylender promising “cash from £20 to £10,000 on ladies’ or gentlemen’s note of hand alone, without security. No fees. No inquiries. Absolute privacy guaranteed” (59). Although the moneylender refuses to provide the desired loan to such youthful clients and warns them that the Jobbins advertisement is fraudulent, and, although experience has shown that Dora’s “face came all red and rough when she used the Rosabella soap that was advertised to make the darkest complexion fair as the lily” (88),[5] the children’s faith in advertising remains unshaken throughout the novel. What Nesbit invokes here is the power of the text, and specifically the commercial and overtly manipulative text, to shape its reader’s vision of the adult world. Fraudulent though these advertisements may be, their very power to mislead depends upon one’s willingness to take them at face value as reliable guides in decision-making, as the Bastables do. While the Bastables also consume texts whose primary audience is children, the importance of the advertisement aimed ostensibly at adults indicates that in the realm of reading, there is no separate and protected space for the young. Just as Nesbit’s work was serialized in periodicals bought primarily by adults, children are always already implicated in the marketplace.

Newspapers and Magazines

Shortly after they encounter the Bovril sign with its impressive “coloured lights,” Oswald and Noël arrive at their destination, the offices of the Daily Recorder. The main office shares the technological sophistication of the sign; Oswald describes it as “a big office, very bright, with brass and mahogany and electric lights” (29). The physical similarity between sign and building hints at the relationship between the enterprises that they represent, in that both advertising and news reporting seem to occupy a space on the boundary between fact and fiction. This space, Nesbit implies, is where life is turned into commodity and where it successfully generates capital. While the newspaper’s editor is housed in a less immediately impressive building (“a very dull-looking place” [29]), this structure too is large and impressive. Oswald comments upon its association with the technology of print, which produces “a queer sort of humming, hammering sound and a very funny smell” of ink (30), and, tellingly, upon the luxury of the editor’s quarters, with their expensive carpet and generous fire. The boys succeed in selling one of Noël’s poems and a human-interest tidbit from Oswald about the comportment of the politician Lord Tottenham when he thinks himself unobserved. Their achievement, which blends art and reportage, makes the excursion to the newspaper the most unambiguously successful of the children’s attempts at money-making and reinscribes the importance of the Press.

This importance is also emphasized in and connected to the text’s discourse on advertising, since, hoardings and electric signs notwithstanding, newspapers are clearly the primary medium through which the Bastables encounter and are duly inspired by advertisements. When in the chapter entitled “The Nobleness of Oswald” the children decide to invent a profitable patent medicine, they expect to use newspapers to get the word out. Dicky, ever uncertain about the relationship between advertisements and factual reporting, plans “that when we had invented our medicine we would write and tell the editor about it, and he would put it in the paper, and then people would send their two and ninepence and three and six for the bottle nearly double the size, and then when the medicine had cured them they would write to the paper and their letters would be printed” to testify to the medicine’s efficacy (87). As Richards notes, “Of all the newspapers in England, only the British Medical Journal, the organ of the ![]() British Medical Association, made it a policy to refuse patent medicine advertisements. The rest justified accepting them by telling themselves, as one member of the Select Committee phrased it, ‘everyone else does it, and we will’” (178). For adults as for children, advertising – including advertising of a morally suspect nature because of its potential for damaging the gullible – was an inescapable part of late-Victorian newspaper consumption.

British Medical Association, made it a policy to refuse patent medicine advertisements. The rest justified accepting them by telling themselves, as one member of the Select Committee phrased it, ‘everyone else does it, and we will’” (178). For adults as for children, advertising – including advertising of a morally suspect nature because of its potential for damaging the gullible – was an inescapable part of late-Victorian newspaper consumption.

The children’s interest in the periodical press is not purely commercial, however, since they also see newspapers and magazines as an important venue for art. “There’s poetry in newspapers,” Alice remarks before her brothers visit the Daily Recorder (24; Fig. 2). While the Bastables are conscious that “editors must be very rich and powerful” and that founding their own story paper might thus lead to treasure (48), the chief interest of the start-up that they title The Lewisham Recorder is as a creative outlet. “Being editors,” Oswald concludes later, “is not the best way to wealth” (58). From the point of view of the author herself, however, the inclusion of the “Being Editors” chapter, which consists largely of the reprinting of the inaugural (and final) Lewisham Recorder number in its entirety, seems to have been motivated by a thrifty desire to recycle and profit anew from “The Play Times,” a three-part serial that significantly predated the Treasure Seekers narrative, having appeared in Nister’s Holiday Annual in 1894, 1895, and 1896. This reuse nicely figures in miniature a point made throughout Treasure Seekers, namely that yesterday’s periodical material, even material that might once have been dismissed as hack work, will reappear as today’s art.

Figure 2: “‘There’s poetry in newspapers,’ said Alice,” illustration by Gordon Browne to the first American edition of _The Story of the Treasure Seekers_ (1899)

Bygone news items and mass-market periodical fiction continue to inspire the children’s cultural discourse throughout the narrative. Treasure Seekers is awash in references to predecessors and contemporaries of Nesbit whose serials had achieved popular success. We see mention of contemporary writers Rudyard Kipling and Arthur Conan Doyle, of earlier writers of penny dreadfuls involving highwaymen Dick Turpin and Claude Duval, and of editors such as Edwin Brett of The Boys of England (popular in the 1860s and after) and Ralph Rollington (John Allingham), founder in 1879 of The Boys’ World and rechristened “Dick Diddlington” in Nesbit’s “Being Detectives” chapter. Nesbit also invokes widely reported events such as the 1860 wreck off Point de ![]() Galle of the steamship Malabar, chronicled by the journalist William Bowlby, a survivor of the event; the Klondike gold rush of 1897; a strike by colliers in South

Galle of the steamship Malabar, chronicled by the journalist William Bowlby, a survivor of the event; the Klondike gold rush of 1897; a strike by colliers in South ![]() Wales in 1898; and political discourse through the figure of the “mad Protectionist” Lord Tottenham. Some of these references were more current in 1899 than others, but Oswald’s narration treats them identically as part of his general knowledge bank, a telescoping of space and time that assists what Anderson calls Nesbit’s programmatic, and protomodernist, “distortions of perspective in time and space” (311).

Wales in 1898; and political discourse through the figure of the “mad Protectionist” Lord Tottenham. Some of these references were more current in 1899 than others, but Oswald’s narration treats them identically as part of his general knowledge bank, a telescoping of space and time that assists what Anderson calls Nesbit’s programmatic, and protomodernist, “distortions of perspective in time and space” (311).

Popular Literature

In addition to the mentions of such favorites of the late-Victorian serial-reading public as Kipling’s Mowgli stories and Doyle’s Sherlock Holmes tales, Treasure Seekers contains an astonishingly wide array of other literary references. Here too we find a consciousness that children’s reading embraces texts for children and adults alike. In Treasure Seekers alone,[6] the Bastables quote or cite a hefty list of works: the French detective stories of Émile Gaboriau (1832-73), Friedrich de la Motte Fouqué’s chivalric romance Sintram and His Companions (1820), The Arabian Nights, Sir Walter Scott’s historical novel The Adventures of Quentin Durward (1823), Lord Byron’s poem “The Destruction of Sennacherib” (1815), Jane Taylor’s nursery poem “Thank You, Pretty Cow” (1824), a novel by Maria Edgeworth (1768-1849), John Keble’s hymn “New Ev’ry Morning” (1827), the traditional tale of the Spartan boy who steals a fox, Psalm 104, Frederick Marryat’s historical novel The Children of the New Forest (1847), Kipling’s short story “Namgay Doola” (1891) and collection Plain Tales from the Hills (1888), Isaac Watts’s didactic poem “Against Quarreling and Fighting” (1815), Edna Dean Proctor’s poem “Heroes” (collected in Poems, 1867), and Alexander Pope’s “An Essay on Man” (1744). The Bastables’ status as readers has not been lost on scholars. Julia Briggs, for instance, sees Oswald’s allusiveness as Nesbit’s recognition of “the way in which literature and journalism shape expectations, both of style and behavior, particularly the expectations of the young and impressionable” (187), while Marah Gubar contends that it enables Nesbit to “demonstrate[e] how saturation in the work of adult authors – coupled with the power of discrimination – enables her child protagonists to usurp the role of author for themselves” (134). Mavis Reimer suggests that at least one of the literary references allows Nesbit to show the children “reading literally the adults’ figurative language” (53), in much the same way that we have seen Dicky misled by his too-trusting reliance on the truth-telling of advertisements, and Erika Rothwell connects the Bastables’ use of their reading to “the general misunderstanding of the adult world that pervades the trilogy.” She discusses Nesbit’s use of “jokes seemingly designed to be understood by and appeal to adult readers before child readers – and at the expense of children – because the joke is often between the adult reader and the author at Oswald’s expense” (62). Critics, in other words, have on many occasions identified as innovative Nesbit’s handling of the relationship between the textual world of adults and that of children, a relationship that I am here connecting to trends in the consumerist mass culture of the 1890s.

Of these scholars’ positions, the closest to that taken in the present article is Briggs’s, with its focus on how the Bastables illustrate that readers do not simply control texts but are also potentially controlled, even written, by them. In itself, Nesbit’s insight here is hardly modernist; Jane Austen, for one, explores it in novels including Northanger Abbey (written 1798-99, published 1817). Yet whereas Austen’s Catherine Morland is led astray by her excessive fondness for a single genre, the Gothic novel, the Bastables are notable for the catholicity of their reading. Moreover, and especially in light of Treasure Seekers’s emphasis on the discourse of contemporaneous advertising, it is worth noting also that the children’s tastes are not in fact limited to their own moment, but extend backward to years significantly predating 1899. That their relationship to the earlier works is immediate and living, in that the reading performed in both leisure time and school hours becomes their own (even becomes themselves) and informs their games, constructs the literate modern subject as surrounded by a kind of textual scaffolding, largely undifferentiated as to target age, that becomes more dense with each new publication or narrative of which the subject is aware, and to which the imagination may connect freely according to the whim of the moment. Oswald’s evident perception that this scaffolding confers increased scope for mental play thus supports Gubar’s insight that, at least as Oswald himself sees them, the Bastables’ borrowings are empowering. Yet the hint of condescension toward Oswald on Nesbit’s part, detected by Reimer and Rothwell in the comic misquotation of literary allusion, simultaneously points to the idea that the child may be less free than he perceives himself to be, that his imagination is in effect being colonized by adult marketers of products, concepts, and even virtues.

History: The Death of Nelson

Since the present article begins by invoking Nesbit’s contradictory use of bygone conventions, it seems appropriate to end with a discussion of Treasure Seekers’s handling of a particular historical event, namely the 1805 death of Horatio, Lord Nelson during the battle of ![]() Trafalgar. With the exceptions of the Gunpowder Plot of 1605, which shows up several times in the text via mentions of the various trappings of the Guy Fawkes Day holiday, and the dual references to the historical highwayman Claude Duval (which appear to be filtered through the pages of sensational fiction), Nelson’s death is the only historical reference to surface more than once, and it is certainly the one that is handled at the greatest level of detail. Oswald invokes it in no fewer than three chapters: “Lord Tottenham,” in which the title character’s face is compared to that of the dying naval hero; “The Robber and the Burglar,” in which the familiarity of the “robber” (actually a friend of the children’s father) with the Nelson saga establishes for Oswald that “he was really a man who had been to a good school as well as to Balliol” (102); and “The Divining Rod,” in which the children take H.O.’s injury in a minor domestic accident as the occasion for a reenactment of the famous death scene. Clearly, the scene has a considerable hold over the children’s imagination, and it is thus worth examining the uses to which they, and Nesbit, put the reference.

Trafalgar. With the exceptions of the Gunpowder Plot of 1605, which shows up several times in the text via mentions of the various trappings of the Guy Fawkes Day holiday, and the dual references to the historical highwayman Claude Duval (which appear to be filtered through the pages of sensational fiction), Nelson’s death is the only historical reference to surface more than once, and it is certainly the one that is handled at the greatest level of detail. Oswald invokes it in no fewer than three chapters: “Lord Tottenham,” in which the title character’s face is compared to that of the dying naval hero; “The Robber and the Burglar,” in which the familiarity of the “robber” (actually a friend of the children’s father) with the Nelson saga establishes for Oswald that “he was really a man who had been to a good school as well as to Balliol” (102); and “The Divining Rod,” in which the children take H.O.’s injury in a minor domestic accident as the occasion for a reenactment of the famous death scene. Clearly, the scene has a considerable hold over the children’s imagination, and it is thus worth examining the uses to which they, and Nesbit, put the reference.

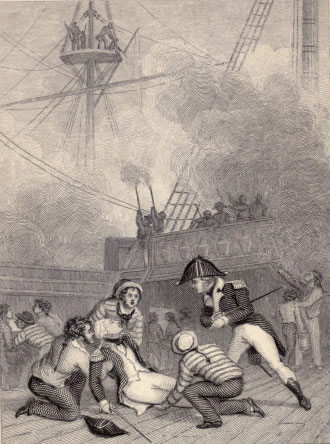

In Robert Southey’s Life of Lord Nelson (1813), the hero’s dying words are said to have been, “Take care of my dear Lady Hamilton, Hardy, take care of poor Lady Hamilton. Kiss me, Hardy. Now I am satisfied. Thank God I have done my duty. . . . God bless you, Hardy. I wish I had not left the deck; for I shall soon be gone. Doctor, I have not been a great sinner. Remember that I leave Lady Hamilton, and my daughter Horatia, as a legacy to my country. Thank God I have done my duty!” (qtd in “Review” 470). The portions of this deathbed scene incorporated into Oswald’s accounts reflect the story as sanitized for children, inasmuch as Lady Hamilton and Horatia (an embarrassing “legacy” by Victorian standards) are absent and there is no suggestion of sin large or small. Rather, the three Nelson references point to the importance of both visual and verbal historical representation. In the first mention, Lord Tottenham, “look[ing] like the Death of Nelson, for he is clean shaved and it is a good face,” instructs the children after discovering that they have set their dog on him in the hope of being rewarded for rescuing their victim, “Always remember never to do a dishonourable thing, for money or for anything else in the world” (72). Oswald’s reference to Lord Tottenham’s appearance points the reader to the various history paintings designed as martial Pietàs showing the recumbent Nelson as the center of a group of anxious shipmates (see Figure 3 for a typical image); such images emphasize Nelson’s nobility and self-sacrifice on the altar of country. In the second scene, the presumed “robber,” Mr. Foulkes, follows tall tales of having been serially a highwayman and a pirate with the claim that he had to give up the latter trade “because I could not get over the dreadful sea-sickness.” When Oswald responds, “Nelson was sea-sick,” Foulkes’s rejoinder is, “I hadn’t his luck or his pluck, or something. He stuck to it and won Trafalgar, didn’t he? ‘Kiss me, Hardy’ – and all that, eh? I couldn’t stick to it – I had to resign. And nobody kissed me” (102). The allusion in this exchange, with its quotation of the iconic line “Kiss me, Hardy” and its invoking of Nelson’s perennial mal de mer, is clearly to a work of prose rather than a painting, but again the emphasis is on Nelson’s virtue, in this case tenacity and resulting success despite discomfort. Finally, when H.O. falls, bumps his head, and is inclined to howl, “We bandaged his head with a towel, and then he stopped crying and played at being England’s wounded hero dying in the cockpit, while every man was doing his duty, as the hero had told them to, and Alice was Hardy, and I was the doctor, and the others were the crew” (109). Blending the visual and the verbal, this iteration savors more of the dramatic than of the didactic, although the reference to duty ensures that the latter element will not be absent.

Nesbit’s repetition and variation of the Nelson trope hints at the mass-marketing of the lessons that written and painted hagiographies were used to communicate. That is, although the point of the valorization of Nelson by those who provided representations of his death scene to a nineteenth-century British audience was to identify him as a useful exemplum precisely because he was unusual, the story and allied images became so familiar to late-Victorian children that they may be likened to an advertising campaign, in this case selling not a commercial product such as Hornby’s Oatmeal but a moral product in the form of a particular set of virtues that the young are to emulate. Just as Dicky, say, is marked by his readiness to succumb to the blandishments of newspaper advertisements, Oswald’s attitude toward Nelson contains no skepticism. Yet Foulkes’s linking of the Nelson death scene with his own spurious claims about a past as highwayman and pirate suggests that all these accounts are equally a matter of myth, and a myth that is moreover generic and oversold, the stuff of penny dreadfuls in the first instance and dime romances in the second. While Oswald’s mention of Nelson’s seasickness is admiring, in the hands of the adults (and Nesbit still more than Foulkes) the malady becomes comically prosaic, a way of puncturing grandiosity and bringing heroism back down to earth. In other words, whereas elsewhere in the narrative it is often Oswald who is shown rejecting sentiment and the adult reader who is apparently expected to embrace it, the use of the Nelson trope inverts this pattern. Yet to complicate matters further, the final playacting of the death scene suggests that Oswald’s nostalgic attraction to Nelson’s end may come as much from an appreciation of the glamor of a really good martyrdom – the very quality that makes it such successful fodder for mass consumption – as from idealism.

Conclusion

In his introduction to The Nineteenth-Century Child and Consumer Culture, Denisoff argues that “[c]onsumer culture was a large-scale phenomenon that relied for its development on small-scale acts of identity formation, acts that were often most readily fulfilled through the young, who were seen as especially open to and in need of influence, control and shaping” (1). Denisoff goes on to quote Mike Featherstone’s observation that “consumer culture through advertising, the media, and techniques of display of goods, is able to destabilize the original notion of use or meaning of goods and attach to them new images and signs” (7). Foregrounding both the children’s coopting of fragments of other narratives and their susceptibility to being influenced by such narratives, particularly in the case of texts designed for mass consumption, Treasure Seekers plays with the ways in which the modern(ist) child builds identity by shaping and being shaped by the scaffolding of cultural and commercial information that surrounds members of Western society.

If The Waste Land, in Harriet Davidson’s words, “treats myth, history, art, and religion as subject to the same fragmentation, appropriation, and degradation as modern life,” offering the reader only the choice between “confusion” and “a barren waste” (123), Davidson simultaneously observes that for many readers the effect of the presence of the notes to T. S. Eliot’s poem, which privilege “the scholarly exegesis of sources and allusions,” was to promise – perhaps insincerely – an antidote to the despair of fragmentation (124-25). In contrast, Treasure Seekers implicitly presents its textual scaffolding as both a support for and a boundary for play, fragmentation as evidence of both imaginative riches and the omnipresence of a consumerist culture as chaotic as the pictured scene on Nelson’s flagship. In a delicate balancing act, Nesbit shows the sinister side of popular culture by dwelling on the naïve consumer’s tendency to absorb the rhetoric of advertisements too unsuspiciously. At the same time, however, she demonstrates through the Bastable children’s ability to incorporate other forms of reading into daily life that this very susceptibility to text may be a source of pleasure as much for the children themselves as for the adult members of the audience that Oswald addresses. The indeterminacy of Nesbit’s text, its simultaneous acceptance of the status of commodity and criticism of the culture of commodification,[7] positions it, Janus-like, on the boundary between past and future.

published August 2014

HOW TO CITE THIS BRANCH ENTRY (MLA format)

Nelson, Claudia. “Mass Media Meets Children’s Literature, 1899: E. Nesbit’s The Story of the Treasure Seekers.” BRANCH: Britain, Representation and Nineteenth-Century History. Ed. Dino Franco Felluga. Extension of Romanticism and Victorianism on the Net. Web. [Here, add your last date of access to BRANCH].

WORKS CITED

Anderson, Susan. “Time, Subjectivity, and Modernism in E. Nesbit’s Children’s Fiction.” Children’s Literature Association Quarterly 32.4 (Winter 2007): 308-22. Project Muse. Web. 12 May 2013.

Briggs, Julia. A Woman of Passion: The Life of E. Nesbit 1858-1924. New York: New Amsterdam Books, 1987. Print.

Davidson, Harriet. “Improper Desire: Reading The Waste Land.” The Cambridge Companion to T. S. Eliot. Ed. A. David Moody. New York: Cambridge UP, 1994. 121-31. Print.

Denisoff, Dennis. “Small Change: The Consumerist Designs of the Nineteenth-Century Child.” The Nineteenth-Century Child and Consumer Culture. Ed. Dennis Denisoff. Burlington, VT: Ashgate, 2008. 1-25. Print.

Gubar, Marah. Artful Dodgers: Reconceiving the Golden Age of Children’s Literature. New York: Oxford UP, 2009. Print.

Nesbit, E[dith]. The Story of the Treasure Seekers and The Wouldbegoods. Ed. Claudia Nelson. Houndmills, Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, 2013. Print.

McClintock, Anne. “Soft-Soaping Empire: Commodity Racism and Imperial Advertising.” Travellers’ Tales: Narratives of Home and Displacement. Ed. George Robertson et al. New York: Routledge, 1994. 128-52. Print.

Reimer, Mavis. “Treasure Seekers and Invaders: E. Nesbit’s Cross-Writing of the Bastables.” Children’s Literature 25 (1997): 50-59. Project Muse. Web. 12 May 2013.

Review of The Life of Lord Nelson, by Robert Southey. Orig. Critical Review July 1813. Rpt. Analectic Magazine 2 (December 1813): 459-72. Google Books. Web. 16 May 2013.

Richards, Thomas. The Commodity Culture of Victorian England: Advertising and Spectacle, 1851-1914. Stanford, CA: Stanford UP, 1990. Print.

Rothwell, Erika. “‘You Catch It If You Try to Do Otherwise’: The Limitations of E. Nesbit’s Cross-Written Vision of the Child.” Children’s Literature 25 (1997): 60-70. Project Muse. Web. 12 May 2013.

Sivulka, Juliann. Soap, Sex, and Cigarettes: A Cultural History of American Advertising. 2nd ed. Boston: Wadsworth, 2012. Print.

Williams, Raymond. “Advertising: The Magic System.” 1980. Rpt. Advertising & Society Review 1.1 (2000): n.pag. Project Muse. Web. 16 July 2014.

ENDNOTES

[1] I thank the anonymous reviewers of this essay for their many helpful suggestions.

[2] Preliminary versions of what would later become chapters in the novel began appearing in the periodical press (in this case Nister’s Holiday Annual) as early as 1894, but regular serialization of material that recurred with only minor changes in the one-volume publication took place in 1898-99, principally in Pall Mall. Although Nister’s Holiday Annual was aimed at children, most of the serial installments were published in periodicals that furnished light reading for an audience primarily composed of adults.

[3] I have chosen this list of products more or less at random from the BOP’s September 1890 issue.

[4] The episode became the third chapter when Treasure Seekers appeared in volume form.

[5] Anne McClintock comments that “Soap advertising . . . [was] at the vanguard of Britain’s new commodity culture and its civilizing mission” (131); Nesbit’s reference to dark complexions recalls McClintock’s observations about the connection of ad campaigns for Pears’ Soap in particular with the implicit promise that Africans might be cleansed and redeemed by incorporation into the British Empire (128).

[6] An equally rich range of texts appears in subsequent Bastable collections, beginning with The Wouldbegoods in 1901.

[7] Similarly, one notes that Nesbit was founding her fortune as a writer by poking fun in this, her first real authorial success, at the Bastables’ mishaps in their attempt to found their own fortune.