Abstract

The introduction of Sholes & Glidden Type-Writer, the first commercially successful instrument for mechanical inscription, played a significant role in adapting alphabetic communications to the exigencies of capitalism as it came to increasingly depend on the transcription and management of printed matter. At a time when government agencies and businesses were seeking greater efficiencies in their clerical workforce, the imagined fit between typing and other kinds of feminine work (needle point and performing on a pianoforte), helped draw large numbers of women into the white-collar workforce. The article concludes by examining how the “irruption of the mechanical” into the act of self expression occasioned by the spread of typewriting was taken up as a theme in the literature of the late-nineteenth century, with particular attention to Bram Stoker’s Dracula (1897).

The typewriter, a mechanical device that allowed the spoken word or hand-written documents to be transcribed as uniform type impressed on standard sized paper with regular margins and borders, was one of the most successful technological innovations of the nineteenth century. It helped not only to transform business practices at a time in which they were becoming more and more dependent on the transcription and management of printed matter, but contributed to the significant rise in the number of middle-class women who were able to enter the white-collar workforce. Beyond the world of the commercial office, the typewriter influenced the way in which many writers composed their works; some taught themselves to type, or had their handwritten manuscripts transcribed by a professional typist, while others, such as Henry James, took to dictating their texts to a typewriting amanuensis, the staccato sound of keys hitting the page providing a kind of percussive accompaniment to their literary endeavors. The introduction of the typewriter thus came to mark a significant moment in the conception of language, the moment in which the private communion of the author with his or her words preserved by handwriting was interrupted by the mechanical order of machines, and the forms of standardization that came with the growth of a fully industrialized and capitalist mode of production impresses itself on the writing process. As Walter Benjamin writes, with the advent of instruments for mechanical inscription, the “precision of typographical forms has directly entered the conception of [the author’s] books” (456). The typewriter was, then, more than a device for accelerating the rate at which hand writing could be transcribed into uniform script, or for making documents easier to file and retrieve; it was first and foremost an agent of modernity.

Like many technological innovations of the nineteenth century, including the telegraph, the phonograph, and cinema, the typewriter has an uncertain paternity. The earliest recorded request for a patent for such a device was granted to an English engineer named Henry Mill in 1714. Mill’s patent describes a machine “for the impressing or transcribing of letters singly or progressively one after another, as in writing, whereby all writings whatsoever may be engrossed in paper or parchment so neat and exact as not to be distinguished from print” (qtd in Bliven 24). Mill’s interest in such an instrument (it is unclear whether or not he ever actually built one) was as an aid to the production of legal documents and public records. Other early experimenters with such instruments were prompted by an interest in assisting those with visual impairments. The earliest extant example of typewriting was composed by a blind Italian countess, Carolina Fantoni, on a machine made for her by her friend, Pellegrino Turri. The two carried on an extended correspondence using Pellegrino’s machine between 1808 and 1810. Though not strictly mechanical, Pingeron’s writing frame of 1784 helped point the way to Pierre Foucauld’s “Radigraphie” of 1839, which was later modified by Louis Braille in his efforts to develop a machine that would emboss a page with a notation system that could be read by the fingers rather than the eye (Adler 162-70).

Over the course of the first half of the nineteenth century, however, experimenters were increasingly motivated by the concern that in the age of the steam engine and electrical telegraphy the quill and ink pen was simply too slow. Expert penmen could only write at about twenty words a minute, whereas a trained operator of a stenographic machine could take two hundred words a minute from dictation, and the introduction of the Morse “sounder,” a device whereby telegraphic signals were transmitted by acoustic means, vastly improved the rate at which telegraphers could send and transmit messages. Numerous amateur inventors and entrepreneurs thus sought to develop mechanical devices to accelerate the alphabet, among them William Austin Burt and John Pratt in the ![]() United States, Xavier Projean in

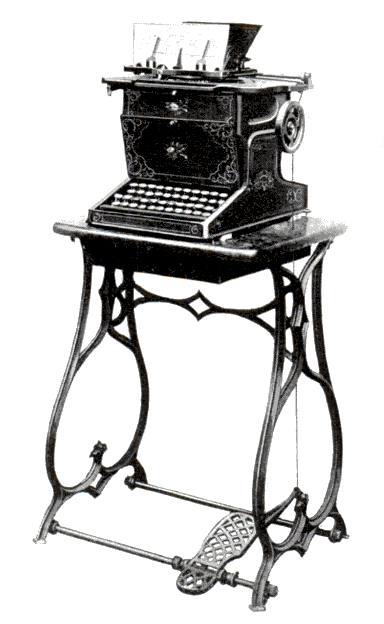

United States, Xavier Projean in ![]() France, and Alexander Bain and Thomas Wright in Great Britain. It was, however, a former newspaper editor, postmaster, and politician, Christopher Latham Sholes, and the mechanic with whom he worked, Carlos S. Glidden, who consolidated these early experiments into the first instrument for mechanical inscription to be manufactured and sold in significant numbers. Sholes began working on his “literary piano” as early as 1867, and together with Glidden, built dozens of proto-types over the course of the next seven years before settling on the configuration that would subsequently define the device: the individual letters of the alphabet and the numbers 2 through 9 were arranged in four rows of keys in the pattern that has hence become familiar as the QWERTY keyboard;[1] depressing any one key caused a bar bearing the relevant typeface at its furthest end to make contact with an ink ribbon and thereby leave an impression of an individual letter on a piece of paper rolled onto a cylinder or platen. Each completed impression caused an escapement mechanism to advance the platen one step, and ready the paper to receive the next letter; a handle allowed the operator to move the page up at the end of a line. It was this device that also sported the name by which all such machines would be known henceforth, the “type-writer.” There were, however, two significant differences between this machine and its later, more common variants. Firstly, Sholes and Glidden’s keyboard caused the type bars to strike upward so that they struck the page from below. The operator thus could not see what he or she had typed until the line was completed and the platen was advanced several lines. Secondly, the machine could only print in upper-case letters, lending its communications a notably emphatic appearance. Unable to raise the capital to manufacture and market the type-writer on their own, Sholes, Glidden and their investors approached the E. Remington & Sons Company, a manufacturer that had made its fortune selling firearms during the Civil War but had branched out to farm machinery and sewing machines in peace time. Remington saw a commercial potential in the instrument, and agreed to produce one thousand machines at its manufacturing facilities in

France, and Alexander Bain and Thomas Wright in Great Britain. It was, however, a former newspaper editor, postmaster, and politician, Christopher Latham Sholes, and the mechanic with whom he worked, Carlos S. Glidden, who consolidated these early experiments into the first instrument for mechanical inscription to be manufactured and sold in significant numbers. Sholes began working on his “literary piano” as early as 1867, and together with Glidden, built dozens of proto-types over the course of the next seven years before settling on the configuration that would subsequently define the device: the individual letters of the alphabet and the numbers 2 through 9 were arranged in four rows of keys in the pattern that has hence become familiar as the QWERTY keyboard;[1] depressing any one key caused a bar bearing the relevant typeface at its furthest end to make contact with an ink ribbon and thereby leave an impression of an individual letter on a piece of paper rolled onto a cylinder or platen. Each completed impression caused an escapement mechanism to advance the platen one step, and ready the paper to receive the next letter; a handle allowed the operator to move the page up at the end of a line. It was this device that also sported the name by which all such machines would be known henceforth, the “type-writer.” There were, however, two significant differences between this machine and its later, more common variants. Firstly, Sholes and Glidden’s keyboard caused the type bars to strike upward so that they struck the page from below. The operator thus could not see what he or she had typed until the line was completed and the platen was advanced several lines. Secondly, the machine could only print in upper-case letters, lending its communications a notably emphatic appearance. Unable to raise the capital to manufacture and market the type-writer on their own, Sholes, Glidden and their investors approached the E. Remington & Sons Company, a manufacturer that had made its fortune selling firearms during the Civil War but had branched out to farm machinery and sewing machines in peace time. Remington saw a commercial potential in the instrument, and agreed to produce one thousand machines at its manufacturing facilities in ![]() Ilion, New York.

Ilion, New York.

The records show that the education committee of the Association discussed for a long time the physical danger of so arduous an undertaking. Finally the decision was made that there should be a thorough physical examination of all the applicants and that those who passed such an examination satisfactorily would be given a trial. The opinion was expressed, however, that the female mind and constitution would be certain to break under the strain. (Sims 84‑85)

Despite such concerns, the eight women who enrolled in the class appeared unharmed by their training and quickly found positions as “type-writer girls,” and their success set the stage for a dramatic change in the public’s understanding of both the place of women in the public sphere, and the role of machines in the new information economy.

The YWCA’s bold step to teach women typing came at a propitious moment, for many businesses were looking for ways to handle the increasing amount of printed matter upon which their operations depended. With the rise of vertically integrated corporations and the development of transnational markets, they required an ever-larger body of clerks to transcribe, collate, and file the masses of paper work generated by their operations.[2] Traditionally, this work was done by men, who demanded a wage sufficient to raise a family, and expected to rise in the ranks and become in due course managers or even partners in the firm.[3] Female typists, by contrast, were willing to accept such work for half the wages that their male counterparts received. Furthermore, they were given to understand that their positions did not entail much in the way of prospects for advancement, and, should they marry, their positions were promptly superannuated. Such strict terms of employment served not only to tamp down the fears of male clerks who felt that women would squeeze them out of jobs they had come to expect as their own, but to answer those critics who argued that paid employment would lure women from the higher moral responsibilities of matrimony and maternity. Following the introduction of the YWCA’s courses, the number of women earning their livelihoods at the keyboard grew dramatically. By the early 1890s, women held nearly 5,600 of the 17,600 positions in the executive departments in ![]() Washington, D. C., and by the turn of the century their numbers had increased to 104,000, or 29 per cent of all the clerical workers in the United States (Aron 836). Similarly, in Great Britain, where the need for a cost-effective means of managing information was particularly pressing given its large overseas colonies, the total number of female clerks, most of whom were either typists or typist stenographers, rose from 2,000 in 1851 to 166,000 by the end of the century, by which time they accounted for twenty per cent of all white-collar workers (Zimmeck 154).[4]

Washington, D. C., and by the turn of the century their numbers had increased to 104,000, or 29 per cent of all the clerical workers in the United States (Aron 836). Similarly, in Great Britain, where the need for a cost-effective means of managing information was particularly pressing given its large overseas colonies, the total number of female clerks, most of whom were either typists or typist stenographers, rose from 2,000 in 1851 to 166,000 by the end of the century, by which time they accounted for twenty per cent of all white-collar workers (Zimmeck 154).[4]

Despite its poor pay and limited opportunities for advancement, work as a typist proved to be an attractive option for many women in the latter decades of the nineteenth century. It was a skill that they could either learn on their own, using one of the numerous instruction manuals that soon flooded the market, or quickly and relatively inexpensively by way of typing classes such as those offered by the YWCA or by one of the newly established secretarial training schools. Moreover, it was one of the few occupations that allowed them to earn an independent income without significant loss of class standing, and which lower-middle-class women might use as a means of social advancement. Type-writing, with its association with other skills deemed distinctly feminine, such as needle work or the ability to perform on a pianoforte, was seen to be well suited for women’s hands. As the author of one typewriting manual puts it: “The type-writer is especially adapted to feminine fingers. They seem to be made for type-writing. The type-writing involves no hard labor, and no more skill than playing the piano” (Harrison 9). Images soon abounded in the newspapers, novels, theatrical plays, and popular post cards of the period, depicting the type-writer girl as leading a life of glamour and adventure. “What she wore,” writes Marshall McLuhan, “every farmer’s daughter wanted to wear, for the typist was a popular figure of enterprise and skill” (228). In novels such as Grant Allen’s The Type-Writer Girl (1897) and Tom Gallon’s The Girl Behind the Keys (1903), the type-writer girl lived on her own, or with another such girl in rented lodgings, spent weekends riding her bicycle (another recent innovation of the period) in the country, and dreaming of the handsome young editor for whom she worked, or solving crimes that relied on her skills at the QWERTY keyboard. Typing, in these colorful narratives, was depicted as an exciting alternative to the role of “angel in the house,” or the drudgery of work as a governess or teacher, and they helped attract many young women into the profession.[5]

The typewriter was more than a solution to the problems of businesses looking to control the costs of managing the mounting tide of information upon which their operations depended, however. For philosophers of language, cultural critics, and literary theorists, the spread of instruments such as those produced by Remington, or by one of its ever increasing number of competitors such as Royal, Hammond, and Underwood, marked the culmination of a process that had begun with the advent of writing itself: the displacement of the human voice and its corollary, the human memory, by our technological prostheses. Among the first to consider the philosophical ramifications of typewriting was Friedrich Nietzsche, whose loss of vision led him to experiment with a Malling Hansen Writing Ball in early 1882. (See Fig. 2.) The instrument, which was unique for the way in which it arranged its fifty-two keys on the surface of a semi-spherical platform poised above a sheet of paper, had preceded the Sholes & Glidden machine to the market by about four years, but never achieved the success of its American counterpart, and remained in limited use on the Continent. The example that Nietzsche received as a Christmas present had been damaged en route, and the philosopher struggled to make it operate smoothly, but it nonetheless prompted him to reflect on the materiality of communication, that is to say, the way in which thought is shaped from the outset by the limitations and possibilities of the technologies we use to express ourselves. Before there is thought, in this view, there is already the instrumental means by which thought is set down in material form, determining in advance its capacity to signify within the cultural and technological norms of the period. The typewriter not only tended to enforce a more careful adherence to standardized orthography, compelling writers to adopt stricter norms with regards to spelling, capitalization, and punctuation. It also introduced a new rhythm and dynamism to the act of self-expression, coupling it to the regular pulsations of the machine age. Or, as Nietzsche put it in a letter to a correspondent, that he laboriously picked out on his malfunctioning writing ball, “You are right—our writing instruments work along with our thoughts” (qtd in Stingelin 81).Nietzsche’s experiments with the writing ball lasted only some six weeks, but his concern for the way the typewriter intruded itself into the act of self expression was subsequently taken up and developed further by Martin Heidegger. For Heidegger, handwriting preserves an intimate relation between man and language; words flow from the mind through the hand to the page in a seamless circuit, and one sees in the particularities of hand writing as much as in the selection of words something of the irreducible singularity of the subject, its unique existence in space and time. This communion of self with self happens in the present; one can see one’s words take shape before one’s eyes, and feel that they are a direct and natural extension of one’s own intentions. Typewriting, by contrast, interrupts this sense of intimacy: each jarring strike of the key on the page breaks the seamless circuit of transmission preserved by handwriting, and, for a single instant, what one writes disappears from view, hidden by the motion of the type bar hitting the page at the type point. In that instant, the self loses contact with its expression, and when the operator pulls the typewritten page from the machine and looks upon its surface, what it reveals appears to belong more to the order of the machine than to the self. The individual particularities of cursive script, those visible signs of one’s unique presence in the physical world, are wholly absorbed by the regular columns of uniform typeface. “In the typewriter,” Heidegger concludes, “we find the irruption of the mechanism in the realm of the word” (85).

Friedrich A. Kittler pushes this concern for “the irruption of the mechanism in the realm of the word” further still, suggesting that the typewriter contributes to the development of a new and radically modern “discourse network,” that is to say, the combination of discourses, institutions, pedagogical practices, and writing tools that taken together determine the limits of what can and cannot be said at any one historical moment. The typewriter, together with the gramophone and the cinematograph, Kittler argues, liberated the word from its anchorage in the human subject; henceforth, words would cease to be grounded in the prior intentions of a speaking subject whose presence would serve to guarantee their meaningfulness. Standardized and uniformly spaced, the typewritten word does not belong to any one person so much as it does to the combinatorial order of the QWERTY keyboard from which it seems to emerge:

In the play between signs and intervals, writing was no longer the handwritten, continuous transition from nature to culture. It became selection from a countable, spatialized supply. . . . Instead of the play between Man the sign-setter and the writing surface, the philosopher as stylus and the tablet of Nature, there is the play between type and its Other, completely removed from subjects. Its name is inscription. (194-95)

The typewriter, in this argument, overturns the hermeneutic faith in the inherent meaningfulness of words, and introduces the possibility of understanding the sign in terms of a differential relationship, a ratio of signal to noise in which meaning arises from the sea of possible combinations, not as the natural or inevitable consequence of a person’s desire to express him or herself. In the “discourse network of 1900,” then, there are no authors giving themselves over to what William Wordsworth called the “spontaneous overflow of powerful feelings,” only information machines exchanging signs as so much abstract matter.

The literature of the nineteenth century often evinces a marked fascination with the typewriter, and the radical transformations it effected in both the make-up of the white-collar workforce, and in the understanding of the signifying function of language in the age of machines. Apart from the novels featuring the adventures of Type-Writer Girls noted above, typists and their struggles to live independent lives are a recurrent topic in New Woman fiction, including George Gissing’s The Odd Women (1893) and Mary Cholmondeley’s Red Pottage (1899). The “world’s first consulting detective,” Sherlock Holmes, explores the peculiar individuality of typewritten script in Arthur Conan Doyle’s short story, “A Case of Identity” (1891), while John Kendrick Bangs satirizes the vogue for séances and automatic writing in The Enchanted Type-writer (1899). But the novel that most fully dramatizes both the instrument’s association with femininity and its pivotal place in the discourse networks of the nineteenth century is Bram Stoker’s Dracula (1897). Though it is often associated with the half-forgotten past of gothic castles and ancient folk myths, much of the action takes place in the modern urban world of Britain’s capital, a city that is “up-to-date, with a vengeance” (36). Dr. Seward records his diaries on a wax cylinder phonograph, the passage of Dracula’s ship is mapped by an elaborate system of look-outs connected by telegraph to England, and Harker impresses the peasants of ![]() Transylvania with his Kodak camera. But if there is a single representative of the emergent discourse network of the nineteenth century it is Mina Harker and her typewriter. Having taught herself typewriting so that she might be of assistance to her fiancé in his legal practice, the novel as we have it is composed entirely of Mina’s typewritten transcripts. Her efforts to “knit together in chronological order every scrap of evidence” not only form the text as such, but also play an active part in defeating Dracula (225). It is her decoding of Jonathan’s shorthand journal of his time in Transylvania that confirms Nosferatu is alive; it is her own typewritten diary that provides the clue that he has come to England; and it is her transcription and collocation of Dr. Seward’s journal that reveals the connection between the vampire and the zoophagous mental patient, Renfield. As her husband writes, “it is due to her energy and foresight that the whole story is put together in such a way that every point tells” (248). Seward concurs: “What a good thing that Mrs. Harker put my cylinders into type! We never could have found the dates otherwise” (225).

Transylvania with his Kodak camera. But if there is a single representative of the emergent discourse network of the nineteenth century it is Mina Harker and her typewriter. Having taught herself typewriting so that she might be of assistance to her fiancé in his legal practice, the novel as we have it is composed entirely of Mina’s typewritten transcripts. Her efforts to “knit together in chronological order every scrap of evidence” not only form the text as such, but also play an active part in defeating Dracula (225). It is her decoding of Jonathan’s shorthand journal of his time in Transylvania that confirms Nosferatu is alive; it is her own typewritten diary that provides the clue that he has come to England; and it is her transcription and collocation of Dr. Seward’s journal that reveals the connection between the vampire and the zoophagous mental patient, Renfield. As her husband writes, “it is due to her energy and foresight that the whole story is put together in such a way that every point tells” (248). Seward concurs: “What a good thing that Mrs. Harker put my cylinders into type! We never could have found the dates otherwise” (225).

While the text seems to pit the “crew of light,” made up of a group of modern, middle-class, urban professionals equipped with the latest hi-tech gadgetry, against the archaic, aristocratic, and altogether more fleshy forces of vampirism, as embodied in the Count and his minions, this nominal opposition soon breaks down. Just as the vampire absorbs the life force of its victims, sucking out of them that which makes them singular and unique, so, too, Mina’s typewriting turns the heterogeneous materials of the novel, the vast collection of diaries, letters, gramophone recordings, newspaper reports, and telegrams from which the text is assembled, into a homogeneous stack of typewritten pages, each following on the last in chronological sequence. Moreover, just as vampirism is a means of reproduction, allowing the Count to create a legion of the undead to do his bidding, so, too, Mina’s typewriting allows her to produce multiple copies of her manuscript. Indeed, when the Count breaks into her bedroom and forces her to take the vampire’s “baptism of blood,” he does so only after destroying what he assumes to be the sole copy of her manuscript. Fortunately, at least for the crew of light, Mina has taken advantage of the “manifolding” function of her typewriter and made a carbon copy. Typewriting thus appears not so much as the antithesis of vampirism as another form of it, a means of transcription and multiplication that is both the central problem of the text and the ostensible solution to that problem. As Jennifer Wicke writes:

The book is obsessed with all these technological and cultural modalities, with the newest of the new cultural phenomena, and yet it is they that shatter the fixed and circumscribed world the novel seems designed to protect through those very means. . . . The same science, rationality and technologies of social control relied on to defend against the encroachments of Dracula are the source of the vampiric powers of the mass cultural with which Dracula . . . is allied. (476-77)

In the end, of course, Dracula is defeated, in no small part due to Mina’s work as a typist, but that work must not be allowed to continue. Mechanical reproduction of the kind she performs with her manifold keyboard necessarily gives way to biological reproduction. In the closing “Note” that her husband appends in a proudly paternalistic gesture, we learn that Mina has become a mother to a child that bears the names of the stalwart men of the crew of light, and her manuscript, or rather the remaining manifold copy of her manuscript, has been put away for the day when her son will be able to read it and learn “what a brave and gallant woman his mother is” (378). In the gender ideology of the Victorian period, this is the appropriate end not just for Mina but all female typists: women’s work managing the information flows upon which the economy increasingly depended is valued and necessary, but it must not interfere with the overriding need to reproduce the social relations of capital. But the text closes with an image of a semiotic order not so much firmly restored as implicitly called into question. Looking back on his adventures with the crew of light, Jonathan Harker is “struck with the fact, that in all the mass of material of which the record is composed, there is hardly one authentic document!” (378). “We could hardly ask anyone,” Jonathan concedes, “even did we wish to, to accept these proofs of so wild a story” (378). The typewriter, Stoker’s novel shows, may have played its part in assuring that middle-class, urban professionals, empowered in part by their command of the new communication technologies of the period, would sweep away the old aristocratic era and come to dominate the social order, but it also left them without the means to claim that victory as their own. In the era of mechanical reproduction, where the individuality of handwriting gives way to uniform type, and every document appears as but a copy of another, the traditional values upon which meaning once depended, those of authenticity, originality, and permanence, begin to recede from view, leaving in their wake, as Mina’s husband laments, “nothing but a mass of typewriting” (378).

published September 2013

HOW TO CITE THIS BRANCH ENTRY (MLA format)

Keep, Christopher. “The Introduction of the Sholes & Glidden Type-Writer, 1874.” BRANCH: Britain, Representation and Nineteenth-Century History. Ed. Dino Franco Felluga. Extension of Romanticism and Victorianism on the Net. Web. [Here, add your last date of access to BRANCH].

WORKS CITED

Adler, Michael H. The Writing Machine. London: George Allen & Unwin, 1973. Print.

Allen, Grant [“Olive Pratt Rayner”]. The Type-Writer Girl. London: C. Arthur Pearson, 1897. Print.

Aron, Cindy S. “‘To Barter Their Souls For Gold:’ Female Clerks in Federal Government Offices, 1862-1890.” Journal of American History 67 (1980‑81): 835‑53. Print.

Bangs, John Kendrick. The Enchanted Type-writer. New York: Harper, 1899. Print.

Beeching, Wilfred A. Century of the Typewriter. London: Heinemann, 1974. Print.

Benjamin, Walter. “One-Way Street.” Walter Benjamin: Selected Writings. Ed Marcus Bullock and Michael W. Jennings. Vol. 1. Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard UP, 1996. I: 444-88. 5 vols. Print.

Bliven, Bruce, Jr. The Wonderful Writing Machine. New York: Random House, 1954. Print.

Cholmondeley, Mary. Red Pottage. London: Edward Arnold, 1899. Print.

Doyle, Arthur Conan. “A Case of Identity.” The Strand II (1891): 253. Print.

Gallon, Tom. The Girl Behind the Keys. London: Hutchinson, 1903. Print.

Gissing, George. The Odd Women. London: Lawrence and Bullen, 1893. Print.

Harrison, John. A Manual of the Type‑Writer. London: Isaac Pitman, 1888. Print.

Headrick, Daniel R. The Tools of Empire: Technology and European Imperialism in the Nineteenth Century. Oxford: Oxford UP, 1981. Print.

Heidegger, Martin. Parmenides. Trans. Andre Schuwer and Richard Rojcewicz. Bloomington, Indiana UP, 1992. Print.

Keep, Christopher. “The Cultural Work of the Type-Writer Girl.” Victorian Studies 40 (1997): 401-26. Print.

Kittler, Friedrich A. Discourse Networks 1800/1900. Trans. Michael Meteer et al. Stanford: Stanford UP, 1990. Print.

McLuhan, Marshall. Understanding Media: The Extensions of Man. New York: Signet, 1964. Print.

Price, Leah and Pamela Thurschwell, eds. Literary Secretaries / Secretarial Culture. Aldershot, Hampshire: Ashgate, 2005. Print.

Richards, Thomas. The Imperial Archive: Knowledge and the Fantasy of Empire. London: Verso, 1993. Print.

Sims, Mary S. The Natural History of a Social Institution: The Young Women’s Christian Association. New York: The Women’s Press, 1936. Print.

Stingelin, Martin. “Comments on a Ball: Nietzsche’s Play on the Typewriter.” Materialities of Communication. Eds. Hans Ulrich Gumbrecht and K. Ludwig Pfeiffer. Trans. William Whobrey. Stanford: Stanford UP, 1994. 70-82. Print.

Stoker, Bram. Dracula. [1897] Oxford: Oxford UP, 1983. Print.

Twain, Mark. Mark Twain’s Letters. Eds. Edgar Marquess Branch, Michael B. Frank, and Kenneth M. Sanderson. Vol. 6. Berkeley, CA: U of California P, 2002. 6 vols. 1982-2002. Print.

Wershler-Henry, Darren. The Iron Whim: A Fragmented History of Typewriting. Toronto: McClelland and Stewart, 2005. Print.

Whalen, Thomas. “Office Technology and Socio-Economic Change 1870‑1955.” IEEE Technology and Society Magazine 2 (1983): 12‑18. Print.

Wicke, Jennifer. “Vampiric Typewriting: Dracula and its Media.” ELH 59 (1992): 467-93. Print.

Wild, Jonathan. The Rise of the Office Clerk in Literary Culture, 1880-1939. Houndmills, Basingstoke, Hampshire: Palgrave Macmillan, 2005. Print.

Yasuoka, Koichi and Motoko Yasuoka. “On the Prehistory of QWERTY.” Zinbun 42 (2011): 161-174. KURENAI. Web. 9 Sept. 2013

Zimmeck, Meta. “Jobs for the Girls: The Expansion of Clerical Work for Women, 1850‑1914.” Unequal Opportunities: Women’s Employment in England, 1800-1918. Ed. Angela V. John. Oxford: Blackwell, 1986. 152-77. Print.

ENDNOTES

[1] The origins of the QWERTY keyboard have been the source of some controversy. According to the earliest histories of the typewriter, which drew upon the correspondence between Sholes and his business partner, James Densmore, the first arrangement of the keyboard was alphabetical, with the expectation that this would have allowed novice operators to most quickly find the letters they desired. A remnant of the arrangement is still evident in the middle row, where F – L appear in the alphabetical sequence, with only the vowel I raised to the row above. As the escapement mechanism that moved the carriage from right to left became more efficient, however, Sholes found that the type bars tended to clash at the type point when the typist was operating at speed. To limit such occurrences, he drew upon his experience as a printer to rearrange some of the more common letter pairs so that they could not be struck in quick succession. According to what we might call the “clashing type bar” theory, QWERTY was simply a mechanical arrangement devised to slow down the typist, and later efforts on behalf of the manufacturers to claim that it was a “scientific” arrangement of the letters designed to ensure “the minimum movement of the hands” was, in the words of one commentator, “probably one of the greatest confidence tricks of all time” (Beeching 40). Physiological studies of hand action seem to support this claim. According to Bruce Bliven, Jr.’s assessment of possible key strokes, the QWERTY arrangement is decidedly sinister, favouring the typist’s left hand over the right (and this despite the fact that most people are right-handed). Moreover, it assigns an inordinate amount of work to the weakest fingers, and requires more reaching from one end to the other than is necessary. Bliven thus concludes, “from the standpoint of the touch typist, this arrangement is madly inconvenient” (145).

The claim that generations of keyboard users (the computer keyboard in most English-speaking countries continues to follow the QWERTY lay out) have been victims of a confidence trick designed simply to protect the vested interests of the manufacturers who had endorsed the “universal keyboard” has been contested in recent years, however. Koichi and Motoko Yasuoka, in a paper published in 2011, dismiss the clashing-type-bar theory as “nonsense,” suggesting that Sholes’ intention was not to slow down typists so much as to accommodate the needs of telegraphists, who were among the first to express at least some interest in the machine (170). They argue that the QWERTY arrangement was the result, then, of Sholes efforts to address a variety of demands over time. Further improvements were introduced by the engineers at Remington looking to improve the machine’s efficiency while still others resulted from efforts to avoid patent claims. QWERTY was, then, never a wholly rational keyboard answering to the physiology of the human hand, but was, rather, an ad hoc arrangement—it has no self-consistent logic, nor any single fixed origin.

The most notable aspect of the QWERTY keyboard, then, may well be not its arrangement, but its apparent durability. Despite several concerted attempts to introduce more ergonomically efficient lay outs (from the Dvorak Simplified keyboard of the 1930s, to the recent KALQ arrangement designed for the thumb-oriented typing common to smart phones), the QWERTY arrangement continues to be the de facto choice for most keyboard operators in the English-speaking world. The very irrationality of the QWERTY layout, and the ways in which its users become so seemingly attached to it, perhaps speaks most pointedly to the assymetrical relations of power at the human-machine divide, and the way in which the latter tends to impose itself as a “natural” fact on the plasticity of the former. As Darren Wershler-Henry writes, “More than anything else, the QWERTY keyboard is an example of how the arbitrary can become normalized and even lionized. In the age of type balls, daisy wheels, and . . . even word processors, the QWERTY configuration is completely unnecessary, but it still persists” (157). The QWERTY keyboard, in this sense, speaks to our inscription within the machinic order, and the way in which that inscription is experienced as both a kind of subjection (we learn to adapt to the machine, no matter how ill suited it is to our needs) and a form of agency—the means by which we become speaking (or at least typing) subjects within that order.

[2] With the exception of the depression of 1893‑97, American businesses experienced a period of substantial growth in the closing decades of the late‑nineteenth century. In industries such as steel, copper and rail transport, this growth was made possible through “horizontal combination,” in which larger firms bought out their smaller competitors in the same field. These increasingly monopolistic corporations benefited from centralized planning, control, and capitalization. The corollary of horizontal combination was “vertical integration.” A particular characteristic of business expansions at the turn of the century, vertical integration allowed companies to gain greater control of the market for their goods by acquiring and/or entering into competition with their suppliers and their customers. By owning, for example, the manufactory for a consumer product, the principle supplier of raw materials for that product, and the retail outlets which would subsequently sell the product, corporations were able to regulate costs and thereby drive out smaller competitors. On the effects of horizontal and vertical integration on office management, see Thomas Whalen.

[3] On the figure of the male clerk, see Jonathan Wild.

[4] On the role of communication technologies in maintaining Britain’s empire, see Daniel R. Headrick and Thomas Richards.

[5] On the figure of the type-writer girl in the cultural imagination of the late-nineteenth century, see Christopher Keep and Leah Price and Pamela Thurschwell.