Abstract

The arrival of the waltz in England changed both the experience of participating in the ballroom and the cultural impact of Victorian social dance.

At the turn of the nineteenth century, the English ballroom looked much as it had for generations. Minuets continued to hold ceremonial significance, but country dances dominated the dance floor with seemingly endless new variations appearing every Season.[1] In a country dance, men and women stand across from each other in two lines and dance down and across the lines. The dances are comprised of a series of figures, including “turn partners,” “hands four round,” and “lead down the middle,” and the combination and recombination of these figures allowed for the creation of new dances to honor individuals, places, or events. For instance, Thomas Wilson’s 1816 country dance manual, The Treasures of Terpsichore, includes dances titled “The Duchess of York’s Slipper,” “Flowers of Edinburgh,” and “The Downfall of Paris.” Many of the earliest country dances were recorded in John Playford’s 1651 text The Dancing Master, which included dance instruction and music for 150 dances and celebrated this ancient art form, which could aid in “making the body active and strong, gracefull [sic] in deportment” (n.pag.). Indeed, dancing was not only a form of entertainment, it was also a source of physical exercise, a genteel accomplishment, and a ticket to the marriage market.

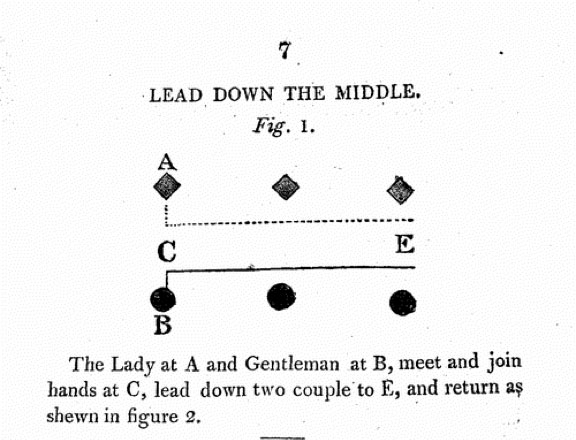

The name “country dance” does not reflect the dance’s rustic origins but rather is a translation of the French contredanse—a reference to the structure of the dance sets in which partners face one another across the dance lines. Country dances are “open couple dances,” meaning that the dancers have limited physical contact with one another, coming together to complete a figure, and then separating and returning home to their places in the line. For example, as shown in Figure 1 from Thomas Wilson’s 1808 manual, Analysis of Country Dancing, Lady A and Gentleman B come together to take hands and dance down the center of the line. They then reverse and return home, each moving to their respective sides of the line.

For over one hundred years, the English ballroom had been characterized by open-couple, figure-based dances, but the arrival of the turning, spinning, closed-couple waltz in 1812 turned the dance world on its head. Instead of changing partners and separating during the course of the dance, participants in the waltz remained locked in an embrace-like hold with a single partner while revolving around the room. Both the proximity of the dancing bodies and the turning motion of the dance created a sense of euphoria previously unknown in the English ballroom. Here, I tell the story of the waltz’s introduction to English society, identify some of the major social and cultural concerns associated with the dance, and demonstrate how it often functioned as an inspiration for and referent within nineteenth-century literature.

Most dance historians cite 1812 as the year of the waltz’s entrée into London, although waltz music had been part of the ballroom repertoire for several decades. Indeed, a number of popular country dances were set to waltz music, such as “The Duke of Kent’s Waltz,” which was named for Queen Victoria’s father and known to be a favorite dance of Jane Austen. Stories about the exact origins of the waltz vary, but it is generally believed to have been derived from the turning movements common in Eastern European folk dances (Katz 525). The ballroom version, however, came to London via Paris and was introduced to English society at ![]() Almack’s Assembly Rooms. Located on King Street in the heart of St. James’s, Almack’s was an exclusive and fashionable dance club that flourished during the Regency.[2] The Wednesday evening balls, overseen by a committee of Lady Patronesses, were attended by anyone who was anyone amongst the ton—the members of the elite, fashionable set—and were notorious for being a “marriage market” for debutantes. Indeed, from the most fashionable London clubs to the humblest rural gatherings, balls and dances were sites of courtship and flirtations that created opportunities for partnerships and matchmaking. Dancing together was often the only opportunity for men and women to come into close physical contact, and this “socially sanctioned form of sexual display” was imbued with clear rules and guidelines regarding the selection of partners and behavior on and off the dance floor (Sulloway 143). As several historians of social dance have demonstrated, the nineteenth-century ballroom was a largely patriarchal and heteronormative space designed to promote socially appropriate matches and reinforce traditional class and gender hierarchies.[3] The waltz, then, with its sexually suggestive partnerings and Continental origins raised the stakes within an already charged social atmosphere.

Almack’s Assembly Rooms. Located on King Street in the heart of St. James’s, Almack’s was an exclusive and fashionable dance club that flourished during the Regency.[2] The Wednesday evening balls, overseen by a committee of Lady Patronesses, were attended by anyone who was anyone amongst the ton—the members of the elite, fashionable set—and were notorious for being a “marriage market” for debutantes. Indeed, from the most fashionable London clubs to the humblest rural gatherings, balls and dances were sites of courtship and flirtations that created opportunities for partnerships and matchmaking. Dancing together was often the only opportunity for men and women to come into close physical contact, and this “socially sanctioned form of sexual display” was imbued with clear rules and guidelines regarding the selection of partners and behavior on and off the dance floor (Sulloway 143). As several historians of social dance have demonstrated, the nineteenth-century ballroom was a largely patriarchal and heteronormative space designed to promote socially appropriate matches and reinforce traditional class and gender hierarchies.[3] The waltz, then, with its sexually suggestive partnerings and Continental origins raised the stakes within an already charged social atmosphere.

Almack’s was a place where the latest fashions in dress and dancing were on display; thus, it was an appropriate venue for the debut of the new fashionable import from the continent: the waltz. Dance historian Phillip J. S. Richardson notes that the waltz “was first seen at Almack’s in 1812, introduced in all probability by travelled aristocrats who had seen it on the Continent” (93). Almack’s, like all ballrooms, was a performance space in which a spectacle/spectator relationship was created between those performing a dance and those watching from the sidelines. Indeed, ballroom dancing made visible dancers’ behavior, courtship, and morality because on the dance floor an individual’s predilections and preferences were publicly displayed. While couples moving through the figures of the country dance would not have prolonged contact, those dancing the waltz would remain in the fixed dance hold, thereby providing an image of partnership upon which spectators could comment.

The early years of the waltz’s arrival in London were marked by skepticism, and nobody was more skeptical than Lord Byron, whose poem “Waltz: An Apostrophic Hymn” appeared anonymously in 1813.[4] Written in the persona of “a country gentleman,” Horace Hornem, esq., the poem liberally skewers the dance itself and the German culture from which it (and the string of Hanoverian monarchs from George I to Victoria) came. Byron’s attention to the sexuality of the dance and the impact of allowing such foreign entertainments into the English ballroom set the stage for the ways that English writers would continue to use the waltz as a literary and cultural referent throughout the nineteenth century.

Byron’s poem personifies the waltz, giving an account of her arrival in England and subsequent influence upon the ballroom. In doing so, the poem paints “Waltz” as a promiscuous and corrupting force, altering the spirit of English dancing and, by extension, English women. In describing the movement of the dance, Byron leaves little to the imagination:

Waltz—Waltz—alone both legs and arms demands,

Liberal of feet—and lavish of her hands;

Hands which may freely range in public sight,

Where ne’er before—but—pray ‘put out the light.’

Methinks the glare of yonder chandelier

Shines much too far—or I am much too near;

And true, though strange—Waltz whispers this remark;

‘My slippery steps are safest in the dark!’ (113-20)

Unlike the social dances that preceded it, the waltz engages the full body of the dancers at all times, as the partners remain in close physical proximity throughout the dance. Thus, hands might freely range over a partner’s body in ways that they had not previously been able to do in a public setting. Both the hold and the pattern of the dance created unique opportunities for physical interaction between partners. In a waltz, the dancers rotate around the room in a large circle, rather than dancing up and down set lines. The uneven lighting of many ballrooms created shadowy corners where dancers could take advantage of being momentarily shielded from the gaze of the spectators to indulge even further in the benefits of such “slippery steps.” Indeed, Edward Reeser includes the following account of the dance from an 1804 German travelogue in his History of the Waltz (1949): “When waltzing on the darker side of the room there were bolder embraces and kisses” (18).

In his prefatory note to the publisher, Byron’s Horace Hornem describes his initial encounter with the dance. Having gone to a ball expecting to see familiar country dances and reels, he is surprised “on arriving, to see poor dear Mrs. Hornem with her arms half round the loins of a huge hussar-looking gentleman. . . and his, to say truth, rather more than half round her waist” (23). Byron depicts the embracing hold of the waltz throughout the poem as an example of the dance’s sexual nature:

Round all the confines of the yielded waist,

The strangest hand may wander undisplaced;

The lady’s in return may grasp as much

As princely paunches offer her to touch.

Pleased round the chalky floor how well they trip,

One hand reposing on the royal hip [.] (192-7)

In “Byron’s Waltz: The Germans and their Georges,” William Childers discusses Byron’s critical attitude toward the Hanoverian kings as expressed in the poem and notes that Byron likely saw the Prince Regent waltz at a private ball in June 1812. This image, Childers suggests, inspired many of the depictions of partnerships in the poem, particularly those in which a large Germanic man is grasping at the waist of a beautiful young girl, and “summed up for the patriotic as well as the puritanical Byron the vulgarity and corruption of England under the German Georges” (93). Indeed, in enumerating the list of “gifts” that ![]() Germany has bestowed upon England, Byron includes “A dozen Dukes—some Kings—a Queen—and ‘Waltz’” (54).

Germany has bestowed upon England, Byron includes “A dozen Dukes—some Kings—a Queen—and ‘Waltz’” (54).

According to Byron, in addition to being politically problematic because of its national origins, the waltz is also unnervingly democratic. Addressing Waltz, Byron writes, “Thee fashion hails—from Countesses to queans [sic], / And maids and valets waltz behind the scenes” (153-4). Not only was the waltz democratic because its popularity was spreading downstairs, as well as upstairs, but the very form of the dance itself was democratic. In a country dance, the dance lines would be arranged in order of social rank. This arrangement was a holdover from earlier court dances such as the gavotte and the pavane in which those dancers with the highest social rank would be located at the “top” of the line—generally, closest to the dais where the royal family would sit. Even without the presence of royalty, however, the tradition of arranging dance lines in order of precedence continued with those of highest social standing or those receiving a particular honor (a new bride, the host of the ball) standing at the top of the room. In his 1870 A Memoir of Jane Austen, the author’s nephew James Edward Austen-Leigh describes the importance of standing and placement in the country dances of the Regency that were enjoyed by his aunt: “Much heart-burning and discontent sometimes arouse as to who should stand above whom, and especially as to who was entitled to the high privilege of calling and leading off the first dance” (34). In contrast, the circular waltz rearranged the space and order of the ballroom. A circle does not have a “top”; therefore, all parties are perceived to be equal as they rotate around the floor. This new dance pattern thus removed one of the key social indicators in the ballroom, rendering it more difficult for individuals to read the social standing of others in the room and maneuver themselves accordingly.

Publishing his poem shortly after the waltz entered English society, Byron raised an early alarm about the potential implications of this foreign import. Although fashionable aristocrats danced the waltz at Almack’s, it would be another four years before the dance became a mainstream fixture in ballrooms, and most dance historians pinpoint its inclusion in the 12 July 1816 Regent’s Fête at ![]() Carlton House as the moment when the waltz became truly integrated into London society. Reactions, of course, were swift and strong, and the response of the London Times (16 July 1816) is worth quoting in full:

Carlton House as the moment when the waltz became truly integrated into London society. Reactions, of course, were swift and strong, and the response of the London Times (16 July 1816) is worth quoting in full:

We remark with pain that the indecent foreign dance called the Waltz was introduced (we believe, for the first time) at the English Court on Friday last. This is a circumstance which ought not to be passed over in silence. National morals depend on national habits: and it is quite sufficient to cast one’s eyes on the voluptuous intertwining of the limbs, and close compressure of the bodies, in this dance, to see that it is far indeed removed from the modest reserve which has hitherto been considered distinctive of English females. So long as this obscene display was confined to prostitutes and adulteresses, we did not think it deserving of notice; but now that it is attempted to be forced on the respectable classes of society by the evil example of their superiors, we feel it a duty to warn every parent against exposing his daughter to so foul a contagion. Amicus Plato sed mogis amica veritas. We pay a due deference to our superiors in rank, but we owe a higher duty to morality. We know not how it has happened (probably by the recommendation of some worthless and ignorant French dancing-master) that so indecent a dance now has for the first time been exhibited at the English court; but the novelty is one deserving of severe reprobation, and we trust it will never again be tolerated in any moral English society. (2d)

This article raises several of the social and cultural concerns that permeated discussions of the waltz and influenced its use in the literature of the period; specifically, it presents the waltz as a threat to national morals, class, and gender. The performance of the waltz at a court function signaled its integration into society and subsequently prompted this author to write back against the widespread adoption of the dance. Although the Times also reported (15 July 1816) that the royal family themselves did not join in any of the dancing, which consisted entirely of waltzes and cotillions, the performance of the waltz in their presence was nonetheless enough to raise concerns. The article speaks to fears about French morality (and, by extension, revolutionary tendencies) infiltrating the court as it argues that “national morals depend upon national habits.” The threat to the modesty of English women is likewise perceived as a problem, and as the century progressed, authors both in England and on the continent would frequently use the waltz as shorthand for immoral behavior. Finally, the article’s attitude toward class, like Byron’s poem, protests the democratization of the waltz. It is the responsibility of the court, the article suggests, to set an example for the rest of society. If that example is wanting, then nothing less than the complete collapse of social order is sure to follow.

Despite such objections, however, waltz mania swept England, and dancing masters took advantage of this opportunity to promote both dancing classes and dance manuals. During the nineteenth century, instruction in dance was largely determined by social class. Upper-class individuals would likely attend a school where dancing was part of the curriculum or receive lessons at home from a traveling dancing master. The “leading Scottish dancing master of his day,” Joseph Lowe, taught the Royal Family and other members of the household at both ![]() Balmoral and

Balmoral and ![]() Windsor from 1852 to 1860 (Thomas 2). Although the majority of the instruction was in traditional Scottish dances, Lowe did include more popular dances such as the waltz and the polka in the lessons. Only the Princes, Princesses, and non-royal members of the household, however, practiced the waltz and the polka. According to Allan Thomas, editor of Lowe’s journal, “Queen Victoria regretted as a young woman that she could not fully participate in this fashionable new dance as it was considered undignified for the Sovereign to dance in the arms of a subject” (9). Here, again, it is the waltz hold that proved problematic. Nonetheless, Queen Victoria worked studiously to learn Scottish Reels and Highland Flings, and holding hands with a subject in practicing these dances was deemed acceptable. Indeed, Lowe includes several accounts of Queen Victoria partnering with his daughter Charlotte during lessons: “Her Majesty enjoying it as much as any of them and felt no hesitation in taking Charlotte’s hand in going round” (53). In addition to showing the popularity of certain dances, Lowe’s journal also reveals the intimate relationship that a visiting dancing master could have with his students, as he records the challenges, triumphs, and joys of the dancers during their lessons. Even Queen Victoria revealed her insecurities, telling Lowe during one of their early lessons, “Oh Mr Lowe, it is all very easy to dance these steps to your violin, but when I come to try them in the evening to the pipes I forget every one of them” (27). Lowe assured the queen that she would improve, and accounts of her practicing and requesting instruction appear throughout the journal. Those middle- or working-class individuals who did not have access to the teachings of a private dancing master might attend a public dancing academy, such as Mr. Turveydrop’s dancing school in Bleak House, which Charles Dickens wonderfully depicts as a site of organized chaos.

Windsor from 1852 to 1860 (Thomas 2). Although the majority of the instruction was in traditional Scottish dances, Lowe did include more popular dances such as the waltz and the polka in the lessons. Only the Princes, Princesses, and non-royal members of the household, however, practiced the waltz and the polka. According to Allan Thomas, editor of Lowe’s journal, “Queen Victoria regretted as a young woman that she could not fully participate in this fashionable new dance as it was considered undignified for the Sovereign to dance in the arms of a subject” (9). Here, again, it is the waltz hold that proved problematic. Nonetheless, Queen Victoria worked studiously to learn Scottish Reels and Highland Flings, and holding hands with a subject in practicing these dances was deemed acceptable. Indeed, Lowe includes several accounts of Queen Victoria partnering with his daughter Charlotte during lessons: “Her Majesty enjoying it as much as any of them and felt no hesitation in taking Charlotte’s hand in going round” (53). In addition to showing the popularity of certain dances, Lowe’s journal also reveals the intimate relationship that a visiting dancing master could have with his students, as he records the challenges, triumphs, and joys of the dancers during their lessons. Even Queen Victoria revealed her insecurities, telling Lowe during one of their early lessons, “Oh Mr Lowe, it is all very easy to dance these steps to your violin, but when I come to try them in the evening to the pipes I forget every one of them” (27). Lowe assured the queen that she would improve, and accounts of her practicing and requesting instruction appear throughout the journal. Those middle- or working-class individuals who did not have access to the teachings of a private dancing master might attend a public dancing academy, such as Mr. Turveydrop’s dancing school in Bleak House, which Charles Dickens wonderfully depicts as a site of organized chaos.

Dance manuals were also extremely popular throughout the nineteenth century and could be used to supplement or sometimes to substitute for formal instruction. More than one hundred dance manuals were published over the course of the nineteenth century, and many circulated on both sides of the Atlantic, as English and American dance masters reproduced one another’s ideas and materials. In addition to including instructions on performing specific dances, dance manuals included advice on preparing for a ball; describing appropriate dress, behavior, and etiquette; providing directions for hosts; and suggesting music. The 1866 manual The Ball-Room Guide includes the following advice: “it is in far better taste to restrict the number of invitations, so that all the guests may be fairly accommodated”; “unmarried ladies should be accompanied by their mothers, or may be under the care of a chaperon”; and “a lady, in dressing for a ball, has first to consider the delicate question of age” (6, 10, 17). Many authors of dance manuals also used the manuals to create business for themselves. For instance, at the end of Thomas Wilson’s 1808 manual An Analysis of Country Dancing, he includes an “Advertisement” inviting those who “wish to acquire a knowledge of Dancing beyond the limits of this work” to pursue further instruction at his studio (140).

As the waltz was both a popular and a potentially scandalous dance, it was in the best interest of dancing masters to attempt to legitimize the waltz, thereby rendering it appropriate for those pupils interested in learning the dance. In doing so, however, they underscored the very concerns about the physicality of the dance and its suggestive nature that were seized upon by critics. For instance, in The Dance of Society (1875), William B. DeGarmo advises, “The gentleman places his right arm round the lady’s waist, supporting her firmly, yet gently. . . . The lady’s left hand rests lightly upon the gentleman’s right arm. . . the fingers together and curved, and not grasping or bearing down upon the gentleman’s arm” (85-6). The lengthy description of the proper hold comprises six full pages in DeGarmo’s manual and addresses proper spacing between partners and the need to remain in perfect sync, lest the gentleman’s hand slip and he be left “grasping” for his partner. Likewise, Henri Cellarius devotes four chapters of The Drawing-Room Dances (1847) to proper placement and execution of the dance. This detailed anatomization of bodies occurred frequently in dance manual accounts of the waltz, and the descriptions are certainly suggestive as body parts and their relation to one another are named and described in painstaking detail. Such accounts of dance also serve to create a discourse of the body—translating the dance into text—that was further explored by authors throughout the century.

Allen Dodworth accompanied his instructions on the waltz hold with illustrations for the reader in Dancing and its Relations to Education and Social Life (1900). Part dance manual, part treatise, Dodworth’s text offers an historical view of the current state of dancing based on his own experience as a dancing master. Dodworth includes a section on “holding partners” in his chapter on round dances and advises, “The manner of holding is, however, of very great consequence, as what is seen in this is frequently used as a measure of character. In this it is the greatest importance” (39). Dodworth’s assertion that the performance of the waltz hold is an indicator of character reinforces the idea that the ballroom is a space for performance, spectacle, and observation in which individual bodies, and the interactions between those bodies, are on display. At the end of the manual, he includes several figures to illustrate these points. The first is labeled “The Proper Way” and the following examples depict the “Extremely Vulgar” position that is not to be tolerated in performing the dance (Figures 2 and 3).

Figures 2 and 3: “The proper way” and “Extremely vulgar” from Allan Dodworth, _Dancing and its Relation to Education and Social Life_ (1900; 274, 277)

The importance of the waltz hold is demonstrated by the continued debate in dance manuals, such as Dodworth’s, about correct performance. Of course, the waltz was not the only closed-couple dance to emerge during the Victorian period. 1844 saw the arrival of the polka, which caused a sensation when it was danced on stage at Her Majesty’s Theatre (Engelhardt 1), followed by the mazurka, and variations on the waltz, including the Boston, flourished. Opponents of the morality of such dances focused on the waltz, however, and dance masters continued to work to legitimize the dance and instill confidence in their students. The moralistic arguments of the waltz’s critics were often broadly anti-dance, but the waltz was repeatedly singled out for special objection. For instance, in From the Ball-Room to Hell (1892), self-identified ex-dancing master T. A. Faulkner describes the experience of a debutante during her first waltz: “It brings a bright flush of indignation to her cheek as she thinks what an unladylike and indecent position to assume with a man who, but a few hours before, was an utter stranger, but she says to herself: ‘This is the position every one must take who waltzes’” (9). Faulkner also offers the following colorful account of the dance’s origins in his 1916 text The Lure of the Dance:

A man by the name of Gault, a French dancing master, originated the waltz in the year 1627. He was licentious in the deepest sense of the word, and gloried in the fact that he had led many girls into lives of sin and shame. He had gone down so low in the moral scale that, finally, in an attempt to ruin his own sister he strangled her to death, for which he was guillotined in 1632. (29)

Needless to say, this account does not reflect that of any other dance historians, but it does effectively tap into anxieties about both ostensibly nefarious French influences and the degradation of women that many conservative commentators associated with the waltz.

As its popularity in the ballroom increased, the waltz began to appear in literary works, serving multiple functions as authors drew on the social and cultural significance of the dance in incorporating it into their texts. For instance, the depiction of a couple waltzing could be sign of (often illicit) intimacy. In Gustave Flaubert’s Madame Bovary (1856), Emma Bovary’s first waltz takes place at a society ball with a titled partner. Flaubert describes the physicality of the encounter in great detail:

They began slowly, then quickened their pace. They whirled and everything whirled around them—lamps, furniture, walls and floor—like a disk on a spindle. As they passed near a door, the hem of Emma’s gown caught on her partner’s trousers; their legs interlocked; he looked down at her, she looked up at him; a kind of torpor came over her and she stopped moving. They began to dance again; drawing her along more swiftly, the viscount led her to a remote corner at the end of the gallery, where, out of breath, she almost fell, and for a moment she rested her head on his chest. (45)

Here, Flaubert captures the experience of spinning wildly while enjoying an intimate embrace in which legs and eyes are locked together. Emma is removed from reality for these few moments and must sit down to gather herself and absorb the aftershock of such an exhilarating encounter. Indeed, Flaubert seems to suggest that the physicality of the experience awakens something in Emma that had previously been dormant. The waltz is significant within the novel as well, of course, because the dance, and the ball at which it takes place, becomes a turning point for Emma, which Flaubert develops to devastating ends. Indeed, for some English readers, the foregrounding of the sexualized and disruptive partnership of the waltz in a French novel would serve to further underscore the idea of the dance as a threatening foreign import.

Less traumatic but equally impactful is the waltz in Anthony Trollope’s Can You Forgive Her? (1864), the first of his Palliser novels. Here, Plantagenet Palliser observes his wife, Glencora, waltzing with her former lover, Burgo Fitzgerald, and although Glencora does not give in to Burgo’s entreaties that she run away with him, the event still causes strife for the recently married Pallisers. Plantagenet accuses his wife of dancing “recklessly” with Burgo: “reckless of what people might say; reckless of what I might feel about it; reckless of your own position” (620). Plantagenet is much more active than Charles Bovary in responding to the situation, and his strong reaction is caused not only by the intimacy of the waltz embrace between Glencora and Burgo but also by the publicity of the dance, which, as in many cases, is the greater offense. His repetitive use of “reckless” echoes the many objections to the waltz, which suggested that the dance promoted the loosening of physical and moral restraints.

The waltz became such a familiar part of literary courtship narratives during the nineteenth century that Anne Thackeray Ritchie bemoaned in her 1865 essay “Heroines and their Grandmothers” how women in Victorian novels “no longer smile and trip through country-dances hand-in-hand with their adorers, but waltz with heavy hearts and dizzy brains, while the hero who scorns them looks on” (490). In addition to marking a change in ballroom fashions, for Ritchie, the waltz also symbolized a move from the heroines of Jane Austen to those of later Victorian novelists. George Eliot, however, creates two heroines who decline to waltz although they recognize the importance of such ballroom partnerships. Maggie Tulliver “could not dance anything but a country dance,” but she nonetheless enjoys the physical proximity offered by the waltz (450). When Stephen Guest approaches her for a waltz, she agrees to a walk instead, and arm-in-arm, they approximate the physical closeness of the waltz. Stephen is clearly moved by the intensity of this experience, as “he darted towards the arm and showered kisses on it, clasping the wrist” (453). Maggie recoils, and as they return inside, Eliot’s narrator notes that “the waltz was not ended,” thereby further aligning their assignation—and the events to come—with the dance (453). In Daniel Deronda, Gwendolen Harleth flatly refuses to put herself in such a position, declaring that she will not waltz because “I can’t bear having ugly people so near me” (96). Gwendolen’s objection to the closed-couple dance reflects her innate snobbery but also a real aversion to the close connection of the waltz hold. This disinclination towards being locked in a partnership may provide some foreshadowing about her marriage to Grandcourt and its consequences.

The waltz also appears in poetry from the period, with some writers borrowing the triple meter of the dance in constructing their own texts. Amy Levy, for instance, uses both the form of the waltz and its cultural implications, specifically those surrounding female sexuality, in her poem “A Waltz Song” in her 1889 collection, A London Plane-Tree and other Verse.[5] The poem begins with a stanza that establishes the tone and meter, borrowing the rhythm of the waltz and moving through iambic trimeters and tetrameters, which lull the reader with soothing repetition:

O sway, and swing, and sway,

And swing, and sway, and swing!

Ah me, what bliss like unto this,

Can days and daylight bring? (1-4)

Like the waltz itself, the poem moves full circle, from the initial idealistic enjoyment of the dance, to the realistic acknowledgement of the social rules and codes employed in the ballroom. In the concluding stanza, Levy gently tweaks the initial verse, inserting her cynical commentary between the steps of the dance to reflect the hollowness of such artificial partnerships, which, from her perspective, cannot produce real, lasting relationships. The concluding stanza echoes the first:

O swing, and sway, and swing,

And rise, and sink, and fall!

There is no bliss like unto this,

This is the best of all. (13-16)

In contrast to the continual movement suggested by the first stanza, the fall in the concluding stanza is a terminal motion that foreshadows the end of the dance, the poem, and the romance of the ballroom partnership. Employing the repetitive and formulaic nature of the waltz itself as a poetic model, Levy challenges the scripted expectations of ballroom courtship, which transform the enjoyment of the dance articulated in the first stanza into a codified encounter in which women are often pressured into partnerships. The final two lines, then, read as a cynical revision of the introduction: “There is no bliss like unto this, / This is the best of all” (15-16). Levy’s final lines bring closure to a poem that calls attention to the constructedness of ballroom courtships and the performance of women within these courtships while also mimicking the movement and rhythm of the very dance form that it critiques.

As with many aspects of Victorian society, the ballroom changed significantly after World War I, and the waltz—once so scandalous and controversial—became a relic of an older age, replaced by raucous Ragtime and salacious Tangos.[6] For nearly a century, however, it had defined the world of social dance, changing the model of partnership within the ballroom and offering inspiration for writers and artists seeking to capture the tension and exhilaration of dance. Moreover, the impact of the waltz and its presence at the forefront of discussions about dance in historical, critical, and literary works produced throughout the Victorian period underscore the importance of dance history to a wide range of cultural, social, and literary narratives.

published April 2016

HOW TO CITE THIS BRANCH ENTRY (MLA format)

Wilson, Cheryl A. “The Arrival of the Waltz in England, 1812.” BRANCH: Britain, Representation and Nineteenth-Century History. Ed. Dino Franco Felluga. Extension of Romanticism and Victorianism on the Net. Web. [Here, add your last date of access to BRANCH].

WORKS CITED

Adburgham, Alison. Silver Fork Society: Fashionable Life and Literature from 1814 to 1840. London: Constable, 1983. Print.

Austen-Leigh, J. E. “A Memoir of Jane Austen.” A Memoir of Jane Austen and Other Family Recollections. New York: Oxford UP, 2002. 1-134. Print.

The Ball-Room Guide. London: F. Warne and Co., 1866. Print.

Buckland, Theresa Jill. Society Dancing: Fashionable Bodies in England, 1870-1920. New York: Palgrave, 2011. Print.

Byron, George Gordon. “Waltz: An Apostrophic Hymn.” The Complete Poetical Works. Vol. 3. Ed. Jerome J. McGann. New York: Oxford UP, 1981. 22-31. Print.

Cellarius, Henri. The Drawing-Room Dances. London: E. Churton, 1847. Print.

Chancellor, E. Beresford. Memorials of St. James’s Street Together with the Annals of Almack’s. London: Grant Richards Ltd., 1922. Print.

Childers, William. “Byron’s Waltz: The Germans and their Georges.” Keats-Shelley Journal 18 (1969): 81-95. Print.

“Dance Called the Waltz.” London Times 16 July 1816, 2d. Print.

DeGarmo, William. The Dance of Society. New York: W. A. Pond & Co. 1875. Print.

Dodworth, Allen. Dancing and its Relations to Education and Social Life. New York and London: Harper and Brothers, 1900. Print.

Eliot, George. Daniel Deronda. New York: Oxford UP, 2009. Print.

—. The Mill on the Floss. New York: Penguin, 1994. Print.

Engelhardt, Molly. Dancing out of Line: Ballrooms, Ballets, and Mobility in Victorian Fiction and Culture. Ohio State UP, 2009. Print.

Faulkner, T. A. From the Ballroom to Hell. Chicago: The Henry Publishing Co., 1892. Print.

—. The Lure of the Dance. Los Angeles: T. A. Faulkner, 1916. Print.

Flaubert, Gustave. Madame Bovary. New York: Bantam, 1976. Print.

Gronow, Rees Howell, Captain. The Reminiscences and Recollections of Captain Gronow: Being Anecdotes of the Camp, Court, Clubs, and Society 1810-1860. 2 vols. London: John C. Nimmo, 1892. Print.

Katz, Ruth. “The Egalitarian Waltz.” What is Dance? Readings in Theory and Criticism. Ed. Roger Copeland and Marshall Cohen. New York: Oxford UP, 1983. 521-32. Print.

Levy, Amy. “A Waltz Song.” A London Plane-Tree and Other Verse. London: T. Fisher Unwin, 1889. Print.

Lowe, Joseph. A New Most Excellent Dancing Master: The Journal of Joseph Lowe’s Visits to Balmoral and Windsor (1852-1860) to Teach Dance to the Family of Queen Victoria. Ed. Allan Thomas. New York: Pendragon, 1992. Print.

Murray, Venetia. An Elegant Madness: High Society in Regency England. New York: Penguin, 1998. Print.

Playford, John. The English Dancing Master. London: Dance Books, 1984. Print.

Reeser, Eduard. The History of the Waltz. Trans. W. A. G. Doyle-Davidson. Stockholm: The Continental Book Company, 1949. Print.

Richardson, Phillip J. S. The Social Dances of the Nineteenth Century in England. London: Herbert Jenkins, 1960. Print.

Ritchie, Anne Thackeray. “Heroines and Their Grandmothers.” Prose by Victorian Women. Ed. Andrea Broomfield and Sally Mitchell. New York: Garland, 1996. 489-504. Print.

Sulloway, Alison. Jane Austen and the Province of Womanhood. Philadelphia: U of Pennsylvania P, 1989. Print.

Trollope, Anthony. Can You Forgive Her? New York: Penguin, 1986. Print.

Wilson, Cheryl A. Literature and Dance in Nineteenth-Century Britain: Jane Austen to the New Woman. New York: Cambridge UP, 2009. Print.

—. “Politicizing Dance in Late-Victorian Women’s Poetry.” Victorian Poetry 46.2 (2008): 191-206. Print.

Wilson, Thomas. An Analysis of Country Dancing. London: J. Berryman, 1808. Print.

—. The Treasures of Terpsichore. London: Sherwood, Neely, and Jones, 1816. Print.

ENDNOTES

[1] The “Season” refers to the time of year (generally late winter through early summer) when members of the fashionable world would come to London to engage in a hectic and high-stakes series of social entertainments and engagements.

[2] For additional discussion of Almack’s, see Alison Adburgham, E. Beresford Chancellor, Captain Rees Howell Gronow, and Venetia Murray.

[3] See Molly Engelhardt’s Dancing out of Line and Cheryl A. Wilson’s Literature and Dance in Nineteenth-Century Britain.

[4] According to Jerome J. McGann, the poem was first published in a small but unknown print run by Sherwood, Neely, and Jones on or before 21 April 1813. It was pirated and reprinted in 1821, and this later edition was the basis for all future editions (Complete Works, Vol. 3, note 191).

[5] For additional discussion of this poem, see Cheryl A. Wilson “Politicizing Dance in Late-Victorian Women’s Poetry.”

[6] Theresa Jill Buckland discusses this period of transition in detail in Society Dancing.