Abstract

The opening of the first direct railway line from London to the Kent coast in 1862 challenged traditional dichotomies between town and country, and contributed to a growing nostalgia associated with the river. Fin-de-siècle writers used the apparent opposition between rail and river, city and country, to ask new questions about the place of women in a rapidly changing world; the transition to a new century further strained the traditional dichotomy between feminised pastoral and masculinised industrial, a tension reflected in the problematic portrayal of rail and water in the work of E. Nesbit.

The impact of the early railway was registered as both exciting and horrifyingly destructive by Victorian writers, perhaps most famously by Dickens in Dombey and Son (1848). Michael Freeman has suggested that the sense of wonder associated with this new form of transport could only really be felt by the first travellers by rail, for whom “history was being written in the present” (19). But as the next generation of writers show, this history was being constantly updated.

The International Centre for Victorian Women Writers digital train adventure “Gates to the Glorious and Unknown” seeks to recreate this sense of rapid and often bewildering change as it follows the character of “Lucy” (named for the heroine of Mary Braddon’s 1862 railway novel Lady Audley’s Secret) down the line from London through the ![]() Medway and along the coast, from her departure in 1862 to her encounter with T. S. Eliot’s

Medway and along the coast, from her departure in 1862 to her encounter with T. S. Eliot’s ![]() Margate in 1922. From the start, treatments of the railway were often a register for wider concerns, not least about changing gender roles, and the website investigates some of the ways in which rail travel – represented as a ‘gendered, masculine space’ (Despotopoulou 9) both expanded and curtailed women’s choices. At a purely practical level, the timetables popularised by Bradshaw were notoriously difficult to follow, leading one guide to comment, ”although we are acquainted with a few of the initiated to whom Bradshaw is as easy as ABC, we have never yet met with a lady who did not regard it as a literary puzzle, while the majority of the sterner sex have failed to master its intricacies” (Railway Traveller’s Handy Book 11).

Margate in 1922. From the start, treatments of the railway were often a register for wider concerns, not least about changing gender roles, and the website investigates some of the ways in which rail travel – represented as a ‘gendered, masculine space’ (Despotopoulou 9) both expanded and curtailed women’s choices. At a purely practical level, the timetables popularised by Bradshaw were notoriously difficult to follow, leading one guide to comment, ”although we are acquainted with a few of the initiated to whom Bradshaw is as easy as ABC, we have never yet met with a lady who did not regard it as a literary puzzle, while the majority of the sterner sex have failed to master its intricacies” (Railway Traveller’s Handy Book 11).

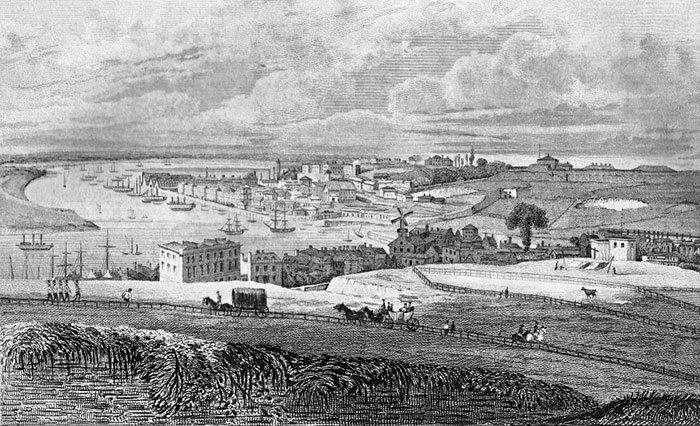

Nonetheless, the railway was in many respects a notable improvement on older forms of transport such as the horse-drawn stage coach, or the crowded hoy boats that had taken up to thirty hours to transport tourists from London to the ![]() Kent coast at the start of the century, before being overtaken by the steam boat by the 1820s. This faster form of transport enabled families to spend longer periods at the seaside, with a so-called ”husbands’ boat” to take the London worker down at weekends, and according to one estimate 98,128 people landed in Margate from the steam vessels coming from London in 1830 (Bonner 1). Like the trains a few years later, hoy boats were often represented as morally dubious in the promiscuous behaviour encouraged by the proximity of male and female travellers, and in this sense the history of the rail network can best be understood in relation to the older narratives of roads and rivers. Indeed the steam boat continued to operate alongside the new railways, with an estimated half of the annual visitors from London to Margate arriving by boat even at the end of the century (Horn 158). Even where it is not directly referenced, the context of an expanding rail network in turn energises literary treatments of water transport throughout the nineteenth century.

Kent coast at the start of the century, before being overtaken by the steam boat by the 1820s. This faster form of transport enabled families to spend longer periods at the seaside, with a so-called ”husbands’ boat” to take the London worker down at weekends, and according to one estimate 98,128 people landed in Margate from the steam vessels coming from London in 1830 (Bonner 1). Like the trains a few years later, hoy boats were often represented as morally dubious in the promiscuous behaviour encouraged by the proximity of male and female travellers, and in this sense the history of the rail network can best be understood in relation to the older narratives of roads and rivers. Indeed the steam boat continued to operate alongside the new railways, with an estimated half of the annual visitors from London to Margate arriving by boat even at the end of the century (Horn 158). Even where it is not directly referenced, the context of an expanding rail network in turn energises literary treatments of water transport throughout the nineteenth century.

The opening of London Victoria in 1862 enabled the first direct line from the metropolis to the Kent seaside resorts via the Medway, with ![]() Charing Cross offering an alternative from 1864. The opening up of direct train routes from London to Kent dramatically cut journey times, in theory at least, and created new ways for Londoners to experience the country and to take cheap holidays to the coast without the discomfort of a six-hour-plus passage by steam boat. But as the holiday resorts seemingly came closer and travel within the UK became a possibility for increasing numbers of the population with the Bank Holiday Act of 1871, the sense of collapsed distance offered innovative ways for writers to present gender and visibility, surveillance and publicity, in the context of new modes of travel.

Charing Cross offering an alternative from 1864. The opening up of direct train routes from London to Kent dramatically cut journey times, in theory at least, and created new ways for Londoners to experience the country and to take cheap holidays to the coast without the discomfort of a six-hour-plus passage by steam boat. But as the holiday resorts seemingly came closer and travel within the UK became a possibility for increasing numbers of the population with the Bank Holiday Act of 1871, the sense of collapsed distance offered innovative ways for writers to present gender and visibility, surveillance and publicity, in the context of new modes of travel.

While mid-Victorian fiction engaged with the impact of an ever-spreading railway network in a number of ways, the more organic progress of the river from country to town continued to provide an unmissable opportunity during these years for writers such as Dickens to make comparisons with fallen women such as the prostitute Martha in David Copperfield (1850). In Martha’s account her damaging sexual encounters are symbolised by the increasing contamination of the river as it moves from the country and into the town. But the creation of new links from London to the country in the 1860s crucially challenged the traditional opposition of industrial/pastoral, and with it the traditional emblem of the river as sexual fall. From the windows of a train it was possible to watch the course of the river from the metropolis through the countryside and back to the sea, undermining Martha’s image of the polluted London ![]() Thames as the final destination of the initially pure spring.

Thames as the final destination of the initially pure spring.

Writers throughout the nineteenth century continued to respond to Dickens, as many of them attest in their memoirs. But with the faster rhythms of rail travel came new types of fiction. Seizing the opportunity offered by W. H. Smith’s railway bookstalls, writers responded with a range of “railway novels” for travellers who tired of admiring the scenery on the journey. For obvious reasons, the highly contemporary sensation and crime fiction of the 1860s often depended for its impact on dramatic high speed chases by rail. But eschewing such frantic reading activity, one guide to the Kent coast in 1874 advised train travellers that “you will have with you newspapers or books, which, if you are wise, you will not have read on the road, as there is much to interest you on every side, if you will only take the trouble to keep your eyes open” (Starey 5).

This warning against railway reading registers the vista opened up by the train windows, but at the same time it implies that the sheer speed of rail travel threatens the traveller’s ability to appreciate the view. In a further paradox, a number of fin-de-siècle texts return to the slower patterns of boating or fishing to suggest the complexities of modern life, although as Alison Byerly reminds us, “Only the availability of rapid transit to popular spots along the river enabled travellers to indulge in the luxury of a leisurely, timeless voyage up or down the Thames” and a number of texts “display the contradictions inherent in a form of excursion that privileges one form of travel while continuing to exploit another” (139). More perceptive observers were deeply conscious of the encroachment of rail travel on the liberty of the river; in making subtle connections between the motif of railway travel and the river trip, now itself figured as a leisure activity requiring both skill and free time, a younger generation of writers found innovative ways to debate gender roles in a rapidly changing world, including an increasingly ambiguous treatment of the river as a symbol of female sexual fall.

By the 1890s, life in the city was featuring as problematic across a range of literary texts, but the idea of the country retreat popularised by Dickens among others was itself under threat. Where the sensation novel had derived much of its shock value from the juxtaposition of apparently opposing types, most obviously the rebelliously “masculine” heroine and her conventionally pure counterpart (who may or may not be as good as she seems), New Woman writers offer more complex and detailed representations of the female experience in an often hostile world. For a heroine who is subject to perpetual pressure, the importance of the river interlude derives from its status as elusive pastoral. But by definition, the railway that brings this idyllic holiday within reach also brings it closer to the city, and so becomes a symbol of both escape and encroachment.

For Jerome K. Jerome, the Thames famously provides an imagined retreat for young bachelors of varying degrees of incompetence, with women’s role clearly defined as the provision of additional comic relief. Anticipating the ”how many men does it take to change a light bulb?” jokes that were a hallmark of popular humour a century later, the narrator of his 1889 bestseller Three Men in a Boat confides to the reader, “Of all experiences in connection with towing, the most exciting is being towed by girls. It is a sensation that nobody ought to miss. It takes three girls to tow always; two hold the rope, and the other one turns round and round, and giggles” (72). It comes as something of a shock to learn that while he draws on the experience of bachelor holidays, the book was written shortly after Jerome’s honeymoon (not to mention that he and the two friends represented by Harris and George were all experienced rowing enthusiasts). Significantly the friends make a spontaneous decision to abandon their holiday and return to town by train when it begins to rain, a reminder that the country retreat is both a fantasy and subject to sudden intervention (albeit comic in this case).

Notwithstanding its otherwise jocose tone, Three Men in a Boat reinforces Dickens’s metaphorical use of the river in its account of an actual suicide, a woman who has drowned herself as a result of “the old, old vulgar tragedy. She had loved and been deceived – or had deceived herself. Anyhow, she had sinned – some of us do now and then” (145). Jerome’s tone is sympathetic, but the more overtly politicised New Woman narratives of the late century complicate such Dickensian invocations of the river as a symbol of seduction and despair. These female-authored narratives seek to reclaim and renegotiate women’s place on the river, marking it as a contested space where they too can escape from the pressures of urban life and the gendered interactions of the city, while demonstrating their athletic ability and skill in navigation. Responding to complaints that women in boating costume were indistinguishable from men, one writer retorted in 1893 that this was an absurd excuse to decry female boaters’ supposed lack of modesty and “If there is a similarity in appearance, it must be because women row like men” (“People, Places, and Things”).

Like Three Men in a Boat, a number of George Egerton’s stories use the industrialised rail network to bring the country idyll within reach of her jaded urban dwellers (unlike J, Harris and George, her protagonists are well versed in railway timetables and so achieve this without spontaneously rerouting trains from Waterloo). An 1892 guide to the river by H. Lewis Jones advises that the Medway is particularly adapted to amateur sailors partly because of the virtual absence of steam boats, with the added advantage that “the tides do not run so hard in the Medway, and there is a capital train service between London and Chatham” (45).

But the increased mobility of women who choose to spend their leisure on or near the water comes at a price. In Egerton’s “A Little Grey Glove” from the collection Keynotes (1893), the wealthy male narrator escapes from the pursuit of marriageable women first in a series of overseas locations and finally in a country inn by “an unknown stream” on the Medway in Kent’ (95). It is here that he meets the mysterious woman whose glove the title references. He has first been attracted by the sight of her work box, containing “A scissors, a capital shape for fly-making; a little file, and some floss silk and tinsel, the identical colour I want for a new fly I have in my head” (98). The translation of this domestic object into fishing tackle is literalised when the unseen angler on the bank of the river who inadvertently throws a hook through the narrator’s ear turns out to be the woman about whom he has been speculating.

It soon becomes apparent that the woman, who is never named, has a secret. “When she is here without getting a letter in the morning or going to town, she seems like a girl. . . . But when she goes to town. . . she comes home tired and haggard looking, an old woman of thirty-five” (106-7). The narrator intuitively identifies this apparent fatigue not with the accepted shocks to the bodily system associated with rail travel (Schivelbush 117), but with the object of her visits as connected with the mysterious letters. Only once she is assured that the narrator has no idea of her identity, having been out of the country for some time, does she explain that her husband has accused her (the inference is, falsely) of adultery with a childhood friend and has just divorced her. In a reminder of the constant traffic of news between the city and the country she tells him that details of the decree nisi have recently appeared in the papers, commenting bitterly that “it is funny (with a hysterical laugh) to buy a caricature of one’s own poor face at a news-stall” (112). This protagonist may utilise the rail network, but unlike the late Victorian travellers identified by Byerly, she clearly does not “revel in the brute efficiency of the railway journey” (147).

The river symbolises a suspension between the old life and the new, rather than being used as a means of transport; but the very fact that it is so easily accessible by rail, ties the protagonist to the city she is trying to escape. Although Egerton never points this out, the river itself would have moved quickly past the train windows. What the train traveller would not have seen from the windows, although it would presumably have felt slightly perilous from the river itself, was the drama being enacted in the early 1890s on the ground between Gillingham and ![]() Chatham Reach (formerly St Mary’s Island). This land was still being reclaimed, and anyone sailing down this stretch of the Medway would have seen “gangs of convicts . . . with warders standing on platforms, armed with rifles to shoot any who might try to escape by swimming across the river” (Jones 57).

Chatham Reach (formerly St Mary’s Island). This land was still being reclaimed, and anyone sailing down this stretch of the Medway would have seen “gangs of convicts . . . with warders standing on platforms, armed with rifles to shoot any who might try to escape by swimming across the river” (Jones 57).

The role played by the river in the literature of seduction, and the negotiation of women’s role as a traveller between city and country, becomes yet more problematic in the twentieth-century fiction of E. Nesbit. In her account, the image of the river retreat breaks down altogether, as the infiltration of the city by pastoral images of flowers and rivers is quickly registered as ambivalent, and becomes increasingly threatening. “What would you do, dear reader,” demands the narrator of the 1909 Salome and the Head, “if at midnight and alone, in a house with no address, you found yourself before your toilet-table, with its neat, familiar furniture of cut-glass and silver, and in your hands the head of a dead man?” (219). “Sylvia” (Alexandra Mundy), the character who finds herself in this unenviable position, is a celebrated dancer at the Hilarity Theatre in London and crucially the head is surrounded by red roses, suggestive of both blood and the ambivalent adoration of the (often predatory) crowds who send flowers in appreciation of her performance as Salome. But the narrative revelation that during her final performances she has been dancing with an authentic severed head, with its highly stylised invocation of Gothic melodrama, is carefully framed by the disruption of pastoral traditions in the wake of the railway network between London and Kent.

Discussing the Victorian anxiety over the impact of the railway on the countryside, Michael Freeman argues that “To talk of railroads and the conquest of nature is, of course, to see nature as external. But nature does not exist independently of man: it is a social construction” (48). Joseph Conrad’s 1906 The Mirror of the Sea registers both water and industry as part of the same landscape experienced in river travel: “This ideal point of the ![]() estuary, this centre of memories, is marked upon the steely grey expanse of the waters by a lightship” (103); similarly, at the opening of the Medway “The famous Thames barges sit in brown clusters upon the water with an effect of birds floating upon a pond” (104).

estuary, this centre of memories, is marked upon the steely grey expanse of the waters by a lightship” (103); similarly, at the opening of the Medway “The famous Thames barges sit in brown clusters upon the water with an effect of birds floating upon a pond” (104).

But in Nesbit’s narrative “nature” is constructed in ways that suggest something close to parody, before finally being exposed as an illusion in which many of the characters are complicit. Reinforcing the collapse of felt distance between town and country, the narrator refers casually to specific trains running through the day, while the imagined links between city and country are reinforced by the recurring image of flowers and gardens. The narrator of Salome and the Head insists on Sylvia’s chameleon-like ability to inhabit a series of stage personae, and for many of her audience her presence invokes the loss of a universalised country idyll.

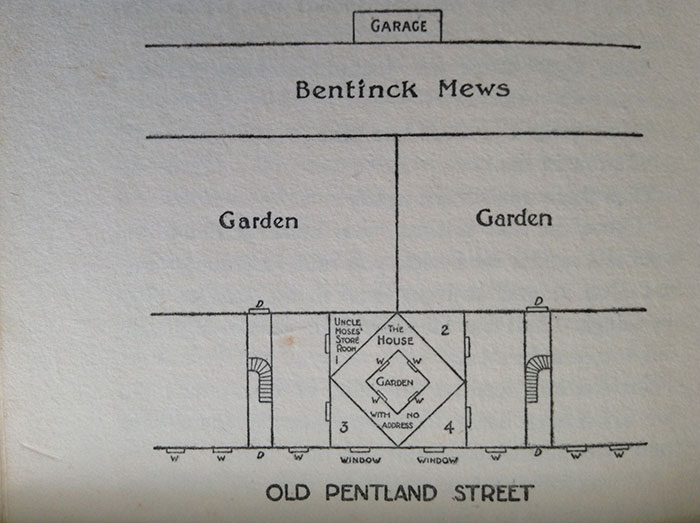

However, this shared absorption in a fantasy of lost innocence co-exists with a desire to possess Sylvia’s body; while the river dance performed for the crowds at the Hilarity is both titillating and for some nostalgic, the effect on male audiences who then seek to buy Sylvia with flowers and jewels reinforces her sense that she can attain privacy only mentally, by “hiding in full view” from the men who pursue her. Indeed, the catalyst for the main plot is the unsuccessful attempt by Edmund Templar to trace her in London, donning an obviously false moustache and following her from the theatre in a taxi. But he is foiled when she apparently disappears from the garage of her own house, rendering herself not only unavailable but also more mysterious and elusive than he had taught himself to believe. It later transpires that she enters the property through a system of trap doors and pulleys, and that the house itself has been constructed by reclaiming rooms from two terraced houses facing on to the street, in a diamond shape. The “house with no address” as it is known in the novel cannot therefore be seen from the road. (See Fig. 1.) Wendy Parkins suggests that “from the New Woman in the suburb to the career woman in a country cottage, heroines are often dislocated from settings where they may seem to belong and are often an unsettling presence for those around them” (11). In this scene, Sylvia is dislocated from the familiar or imagined settings of stage and lodgings by apparently vanishing altogether.

It is an encounter with the taxi driver who drives him to the house with no address (and who turns out to be a disgraced aristocrat whose own honourable behaviour towards Sylvia will finally lead to their marriage) that persuades Edmund of his own guilt in pursuing her as he has done for disreputable ends. His decision to seek her in the country is, therefore, both symbolic and strategic, as he discards his false moustache and decides to present himself under his own name. In Edmund’s second pursuit of Sylvia, the Medway is insistently imbued with images of the Edenic, forcing him to the realisation that he himself may be the tempter who infiltrates and disrupts this idyllic space. Conrad’s description of the Medway stresses that “The estuaries of rivers appeal strongly to an adventurous imagination” (100), and Edmund must learn to distinguish between this type of romantic adventure symbolised by the river and the shady intrigue he has been planning (in the parlance of the time an “adventure” could be used as a masculine code for sexual peccadilloes).

Arriving at the inn in ![]() Yalding, near where Sylvia is believed to spend her one week off in every three, Edmund immediately realises how inappropriate his behaviour has been. This moral awakening is linked directly to his appreciation of his surroundings and his growing awareness of the gap between illusion and reality represented by the river, as he sits in the garden of the inn watching the river, that “decorated with sunlight, looked warm and brown, like the shallow pools whose warmness quite shocks you when you dangle your feet in them from sea-weed-covered rocks. That it was not warm Mr Templar knew, for he had plunged into it at his first awaking” (60).

Yalding, near where Sylvia is believed to spend her one week off in every three, Edmund immediately realises how inappropriate his behaviour has been. This moral awakening is linked directly to his appreciation of his surroundings and his growing awareness of the gap between illusion and reality represented by the river, as he sits in the garden of the inn watching the river, that “decorated with sunlight, looked warm and brown, like the shallow pools whose warmness quite shocks you when you dangle your feet in them from sea-weed-covered rocks. That it was not warm Mr Templar knew, for he had plunged into it at his first awaking” (60).

Having renounced his sham “detective” role, Edmund’s only chance of meeting Sylvia is on the river Medway, where he recognises a river weed growing out of the wall below ![]() Stoneham Lock, because “It was of that trailing stuff that the forest dancer’s wreath had been woven” (63). The river is less regulated and open to surveillance than the railway carriage, but predictably he sees her boat approaching the lock where he is raising the sluices with a crow-bar, and “He was never quite sure whether it was accident or design that made him drop the crow-bar” (65), trapping his fingers under the falling pin. Through this accident (or device) Edmund is able to effect an apparently spontaneous exchange. Indeed, such exchanges are in keeping with the perceived life of the river. As Byerly points out, ”Some accounts note the dreamy meditativeness fostered by the solitary experience of drifting or rowing along the river. Many others, however, stress the social dimensions of river travel, which might involve friends travelling together or interactions with the different boats and parties encountered along the way” (14). Having duly rescued him and bound up his hand, Sylvia takes advantage of the relaxation of social conventions afforded by their encounter, and agrees to a picnic on the river bank: “And you shall tell me your name and station, and we’ll pretend we’ve met at a dinner-party and been properly introduced” (73).

Stoneham Lock, because “It was of that trailing stuff that the forest dancer’s wreath had been woven” (63). The river is less regulated and open to surveillance than the railway carriage, but predictably he sees her boat approaching the lock where he is raising the sluices with a crow-bar, and “He was never quite sure whether it was accident or design that made him drop the crow-bar” (65), trapping his fingers under the falling pin. Through this accident (or device) Edmund is able to effect an apparently spontaneous exchange. Indeed, such exchanges are in keeping with the perceived life of the river. As Byerly points out, ”Some accounts note the dreamy meditativeness fostered by the solitary experience of drifting or rowing along the river. Many others, however, stress the social dimensions of river travel, which might involve friends travelling together or interactions with the different boats and parties encountered along the way” (14). Having duly rescued him and bound up his hand, Sylvia takes advantage of the relaxation of social conventions afforded by their encounter, and agrees to a picnic on the river bank: “And you shall tell me your name and station, and we’ll pretend we’ve met at a dinner-party and been properly introduced” (73).

However, this interlude is immediately compromised by the reappearance of Sylvia’s opportunistic (and presumed dead) husband Isidore Saccage, who had tricked her into marriage some years previously and now plans to blackmail her with the gendered conventions she believes herself to have escaped. Significantly, he insists on a meeting in the garden of her secluded country house, where he threatens her with exposure to the media if she fails to buy him off:

“Shall I tell you what I shall do?” he said. “Yes, I’ll tell you one or two things that I can do. . . . I can let everyone know where you live. No more quiet week-ends with your new friend then. Interviewers and snapshotters: Sylvia in her boat – Sylvia bathing – Sylvia kissing her latest lover under the oak-tree. I can make it impossible for you to do anything without seeing it next day in the paper. I don’t want to drive you to sin, my immaculate lily; but, by God! if you make a slip – even so little a slip as a kiss or two – every office-boy in London shall know it.” (124)

The ease with which unscrupulous London reporters are represented as able to travel down to the Medway for such a purpose convinces Sylvia (unlike the mysterious woman of Egerton’s story) that she cannot escape scrutiny or invasion even in the country.

She herself is still able to recreate the idyll of the river in the theatre itself, if only for the benefit of a paying audience. As she dances, “Old dowagers remembered the sand-castles of their childhood… middle-aged stockbrokers looked on, breathless, and decided to go to the seaside next week-end instead of to the bungalow by the golf-links” (132-133), and she directly draws on the Kentish countryside rather than the landscape in which she grew up for her forest dance: “her memories would not be of the ![]() New Forest, but of trees nearer home, and of the flowers that grow by a Kentish river” (133). However, the subtitle of the novel, “a modern melodrama,” foreshadows the grotesque recalibration of fantasy and lived experience, as roses become blood and wax is replaced with body parts in the final scenes. Nesbit’s biographer comments unsurprisingly that despite her innocence Sylvia “seems to reflect an element of surprising violence within her creator” (Briggs 294).

New Forest, but of trees nearer home, and of the flowers that grow by a Kentish river” (133). However, the subtitle of the novel, “a modern melodrama,” foreshadows the grotesque recalibration of fantasy and lived experience, as roses become blood and wax is replaced with body parts in the final scenes. Nesbit’s biographer comments unsurprisingly that despite her innocence Sylvia “seems to reflect an element of surprising violence within her creator” (Briggs 294).

The illusory nature of Edmund’s own pastoral fantasies is ruthlessly parodied in the descriptions of flowers and ideal landscapes after he discovers Saccage’s decapitated corpse in the garden of the Wood House, where he has arrived at midnight hoping to find Sylvia. The narrator comments that “Murder is an ugly thing; and when it stalks, red-stained, among the flowers and tapers of love’s pretty temple, the flowers are apt to fade and the tapers to go out” (285). Edmund realises that he is covered in blood and symbolically washes his hands of the whole business in the river where he had first shed his own blood in hopes of attracting Sylvia to him: “The river was waiting for him, lying quiet in the moonlight, the river on which he had first seen her. He dipped his hands in the water again and again” (289).

Back in London the house with no address itself incorporates a garden in its centre, and Sylvia’s desolation when Edmund writes implicitly accusing her of murder is contrasted with the false promise of her china and flowers: “There were pink flowers from that garden in a Venice glass on the table; a white cloth too; a chocolate service of Dresden china, pink also, with dainty panels of impossible shepherds and shepherdesses coquetting amid incredible landscapes; silver; the pretty equipage of the first breakfast of a stage marquise” (246). The promise that a pastoral retreat is within easy reach of London by rail is repeatedly undermined by this parody of the imagined landscape; the capacity of the city itself to accommodate the rural setting represented by Sylvia’s river dance is finally destroyed, as Edmund contemplates the easy traffic of media reports first envisaged by Saccage: “64 ![]() Curzon Street was no heaven; if there had been nothing else there was, towards evening, the constant straining of his ears to catch the possible shout of news-vendors: ‘Shocking discovery in Kent! Arrest of the murderer!’” (292)

Curzon Street was no heaven; if there had been nothing else there was, towards evening, the constant straining of his ears to catch the possible shout of news-vendors: ‘Shocking discovery in Kent! Arrest of the murderer!’” (292)

It is his inability to face this possibility that finally alienates Sylvia from Edmund and persuades her to marry a flawed hero with secrets of his own, much as Egerton’s heroine will marry the man who loves her only on condition that he waits for a year and agrees that he will never ask her to reveal her past. In the case of Egerton’s story, this of course means that the reader never learns the secret either, and must accept the mysterious character on her own terms if at all. The narrating protagonist explains that while waiting to be reunited with the woman he is compelled to “haunt the inn and never leave it for longer than a week” (114), leaving the reader to wonder whether this is or is not the right decision.

The wishful nostalgia surrounding life on the river depends for its effect on being set against the rapidity and inevitable crowding of the railway. But where fin-de-siècle authors from Jerome K. Jerome to George Egerton offer the river as a pastoral retreat from the public gaze associated with the metropolis and the railway newspaper stall, Nesbit undermines the idyllic retreat from the public life of the metropolis, suggesting that the separation of city and country through different modes of travel is unsustainable and even illusory.

While the river Medway in fin-de-siècle texts may be envisaged as both unspoiled and healthy, in stark contrast to the ambivalent metaphors of mid-nineteenth century authors such as Dickens who use the Thames as the last refuge of despondent fallen women, the accessibility of the Medway by London rail immediately threatens its status as a rural retreat. Updating Nesbit’s interactive strategy – “What would you do, dear reader, if…?” – by embedding vicarious choices within the story itself, “Gates to the Glorious and Unknown” offers contemporary readers the chance to make responsible but safe vicarious choices on behalf of a Victorian woman travelling alone, or to take the consequences of opting for adventure without the safety net of family structures and cultural convention. While some of her choices result in danger or loss of caste, Lucy’s experience of the shift in outlook that comes with both travel and the acceleration of railway time echoes the defiance of both Sylvia and the unnamed woman of Egerton’s story, who “will make no apology, no explanation, no denial to you, now nor ever” (112).

published September 2016

HOW TO CITE THIS BRANCH ENTRY (MLA format)

Oulton, Carolyn W. de la L.. “‘Coquetting amid incredible landscapes’: Women on the River and the Railway.” BRANCH: Britain, Representation and Nineteenth-Century History. Ed. Dino Franco Felluga. Extension of Romanticism and Victorianism on the Net. Web. [Here, add your last date of access to BRANCH].

WORKS CITED

Bonner, G. W. The Picturesque Pocket Companion to Margate, Ramsgate, Broadstairs and the Parts Adjacent. London: Regent St, William Kidd, 1831. Print.

Briggs, Julia. A Woman of Passion: The Life of E. Nesbit 1858-1924. London: Penguin, 1987. Print.

Byerly, Alison. Are We There Yet? Virtual Travel and Victorian Realism. Michigan: U of Michigan P, 2013. Print.

Conrad, Joseph. The Mirror of the Sea and A Personal Record. Oxford: Oxford UP, 1988. Print.

Despotopoulou, Anna. Women and the Railway 1850-1915. Edinburgh: Edinburgh UP, 2015. Print.

Egerton, George. ‘A Little Grey Glove’. Keynotes and Discords. London: Virago, 1983. 91-114. Print.

Freeman, Michael. Railways and the Victorian Imagination. New Haven: Yale UP, 1999. Print.

Horn, Pamela. Pleasures and Pastimes in Victorian Britain. Stroud: Amberley, 2011. Print.

Jerome, Jerome K. Three Men in a Boat. Oxford World’s Classics. Oxford: Oxford UP, 2008. Print.

Jones, H. Lewis. Swin, Swale and Swatchway or Cruises down the Thames, the Medway and the Essex Rivers. 1892. London: Lodestar Books, 2014. Print.

Nesbit, E. Salome and the Head: a Modern Melodrama. London: Alston Rivers, 1909. Print.

Parkins, Wendy. Mobility and Modernity in Women’s Novels: Women Moving Dangerously. Basingstoke: Palgrave 2009. Print.

‘People, Places, and Things.’ Hearth and Home 28 September 1893. 648. 19th Century UK Periodicals. Gale Document Number: DX1901340024. Accessed 25 February 2016.

Railway Traveller’s Handy Book. 1862. Oxford: Old House Books, 2012. Print.

Rutter, Clem. “Railway Lines in Kent.” Wikipedia: The Free Encyclopedia. Wikimedia Foundation, Inc. 30 April 2007. Web. 19 August 2016.

Schivelbush, Wolfgang. The Railway Journey: The Industrialization and Perception of Time and Space. California: U of California P, 2014. Print.

Starey, W. H. Notes on Margate: Numerous and Humorous. London: J. Newman & Co., 1874. Print.

RELATED BRANCH ARTICLES

Paul Fyfe, “On the Opening of the Liverpool and Manchester Railway, 1830″

Nancy Rose Marshall, “On William Powell Frith’s Railway Station, April 1862″