Abstract

This entry examines a key moment for the British national imagination: the Great Reform Act of 1832 (or First Reform Act). It explores this crisis in aristocratic rule through the prisms of class, religion, geography, and the rise of the popular press, highlighting the concept of “representation of the people” enshrined by the act and the Age of Reform that it inaugurated.

The Act to Amend the Representation of the People in England and ![]() Wales (or Great Reform Act) of 1832 reshaped the political landscape of Great Britain.[1] Yet it did so without producing a significant alteration in the elected government or a massive extension of the franchise.

Wales (or Great Reform Act) of 1832 reshaped the political landscape of Great Britain.[1] Yet it did so without producing a significant alteration in the elected government or a massive extension of the franchise.

By the terms of the constitutional monarchy formed in 1688, the English Parliament represented the interests of the nation by ritually gathering noblemen and bishops in the House of Lords and the (often aristocratic) elected representatives of boroughs and counties in the House of Commons in order to form a government together with the Crown. This system went unchanged even as the Parliament of England and Wales combined with those of ![]() Scotland (in 1707) and

Scotland (in 1707) and ![]() Ireland (in the 1800 Act of Union).

Ireland (in the 1800 Act of Union).

Sparked by riots and electoral rebellion, the Reform of 1832 sought to ensure better “representation of the people” in the House of Commons. The resulting act was designed by its Whig authors to fortify ongoing aristocratic power with the people’s consent. By reforming the House of Commons in response to widespread protests, however, the ruling class in Parliament effectively sanctioned a changing political order. The Great Reform Act thus marks a crucial moment in the history of British political representation.

This entry examines the Great Reform Act of 1832 (or First Reform Act) as a key moment for the British national imagination. It explores this crisis in aristocratic rule through the prisms of class, religion, geography, and the rise of the popular press. Highlighting the concept of representation enshrined by the act and the age of Reform that it inaugurated, it compares the adoption of electoral reform to the evolving practice of parliamentary “privilege.”

Parliamentary privilege, enshrined in the 1689 Bill of Rights, prevented an abuse of royal power by offering legal protection for statements made within the legislative chambers. As the eighteenth-century legal expert William Blackstone described it, “Privilege of parliament was principally established, in order to protect its members not only from being molested by their fellow-subjects, but also more especially from being oppressed by the power of the crown” (qtd. in Chafetz 5). Adopted with the restoration of monarchy after the heady days of the English civil war, it offered constitutional ballast for a balance of power. Yet it could also be used to keep fellow-subjects at bay–or in the dark. In 1727, for example, Edward Cave was imprisoned for writing newsletters containing an account of the proceedings of the House. The full House of Commons affirmed in February 1728 “that it is an indignity to, and a breach of the privilege of, this House, for any person to presume to give, in written or printed newspapers, any account or minute of the debates or other proceedings. That upon discovery of the authors, printers, or publishers of any such newspaper, this House will proceed against the offenders with the utmost severity” (qtd. in Gratton 9). As a standing order of 1738 confirmed, it was a breach of parliamentary privilege to print “any Account of the Debates, or other Proceedings of this House,” and reporters were liable to exclusion at the request of a single Member of Parliament (M.P.) until 1875 (qtd. in Drew 10).

After mobs rioted to protest the imprisonment of newspaper proprietors in 1771, and again in 1810, Parliament came to tolerate unofficial reports, declining either to eject reporters on a regular basis or to prosecute the expansive reports of debates in all the major papers (Gratton 62, 73).[2] In the years between 1810 and 1830, moreover, innovations in newspaper printing, better roads, and faster coaches ensured faster and wider circulation of these reports. Unofficial digests and compilations of the debates also thrived: William Cobbett’s Political Register spawned Hansard’s Parliamentary Debates, and Charles Dickens began work as a parliamentary reporter for his uncle’s encyclopedic venture, The Mirror of Parliament, just in time to witness the debates over parliamentary reform.[3] Although still officially prohibited until 1875, reporting on the debates became an accepted eavesdropping practice. By 1832, the reports of debates were an accepted breach in the age-old privileges of parliament, exposing to public view the leadership of its “lords spiritual and temporal.”

The events surrounding parliamentary reform, likewise, might be seen as a “breach” in a dam–that is, in the fortification of parliament as a stable foundation of the constitutional monarchy. In 1832, this dam was re-formed, with an eye to enduring stability, by affording a different flow. This alteration permitted new kinds of circulation between the subjects of the state and their representatives. In this sense, the galvanizing events of reform constituted a breach of aristocratic privilege. Although the enacted reform was conceived as a permanent solution to the modern problems of parliamentary governance, the reformed government nonetheless found itself in an altered landscape, with the prospect of further breaches to come. Much like the practice of tolerating unofficial reports, in short, the Reform Act did not weaken aristocratic rule in the British parliament so much as it acknowledged and legitimized the ritual breach of ruling class privileges.

1. Rotten Boroughs

It is related . . that Queen Elizabeth . . . was so delighted with some remarkably fine

Hampshire beer . . . that she forthwith erected Crawley into a borough to send two members to Parliament. . . . And though by the lapse of time, and those mutations which ages produce in empires, cities, and boroughs, Queen’s Crawley was no longer so populous a place as it had been . . . – nay, was come down to that condition of borough which used to be denominated rotten–yet, as Sir Pitt Crawley would say with perfect justice in his elegant way, “Rotten! be hanged–it produces me a good fifteen hundred a year.

– W.M. Thackeray, Vanity Fair (ch. 7)

The long tradition of Parliament as the “representative body of the people” was largely symbolic (qtd. in Pitkin 248). As Sir Thomas Smith wrote in 1583, “the Parliament of Englande . . . representeth and hath the power of the whole realme, both the head and the bodie. For everie Englishman is entended to be there present, either in person or by procuration. . . . And the consent of the Parliament is taken to be everie man’s consent” (qtd. in Pitkin 246). Implied consent could benefit the Crown, as Hanna Pitkin notes: “since everyone was presumed to know the actions of Parliament, ignorance was no excuse for disobedience” (85). Yet it also spawned radical visions of a representative legislature as “an exact portrait, in miniature, of the people at large, as it should think, feel, reason and act like them,” as John Adams urged in the American Revolutionary period (qtd. in Pitkin 60). With this in mind, in 1787 the fledgling U.S.A. created a bicameral legislature without hereditary titles, linking representation in the lower House to population surveys. In 1789, the French revolution began with a parliamentary crisis, as the “Third Estate” (representing commoners) defied the king by declaring itself to be a National Assembly, seizing power from the nobility and clergy.

In the light of these radical experiments in democracy, the power retained by hereditary landowners in the British government of the early nineteenth century was remarkable. The United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland continued to be ruled by an hereditary monarchy in tandem with a House of Lords comprised of individuals who were either elevated by the king or inherited the rank from their fathers. Then as now, the only elected Members of Parliament served in the House of Commons.[4] As early as 1641, the House of Commons noted the distinction between “this House, being the Representative Body of the whole Kingdom, and their Lordships, being but as particular Persons, and coming to Parliament in their particular capacity” (qtd. in Pitkin 248).

The difference between the House of Commons and the House of Lords was, moreover, far from crystal-clear in the 1820s, as electoral quirks and an evolving system of patronage ensured a ruling-class monopoly on parliamentary elections. The electoral system hinged on geography and past practice rather than systematic procedures or population surveys. Elites could count upon elections in “rotten” boroughs or “pocket” boroughs where a few electors (often dependent upon their local land-owner) voted in open ballots as their patrons wished. (Borough owners or patrons like the fictional Pitt Crawley of the novel Vanity Fair could “sell” the seats each year for profits.) In districts with larger numbers of electors, meanwhile, votes could be openly purchased and voters openly punished.[5] Electoral seats were given to young men as gifts, and non-aristocratic M.P.’s were rare enough to attract notice.[6] As Lady Cowper wrote in June 1826, “People think this new Parliament will be a curious one . . . such strange things have turned out. There are three stock-brokers in it, which was never the case . . . before” (qtd. in Brock 24).

Paradoxically, it was the government’s effort to share power with a new constituency that revealed for many the “rotten” aspects of such rule.[7] In 1829, Parliament enacted Catholic emancipation (the Roman Catholic Relief Act), which allowed Catholics to serve in Parliament. (See Elsie B. Michie, “On the Sacramental Test Act, the Catholic Relief Act, the Slavery Abolition Act, and the Factory Act.”) Passage of this act was accomplished not due to a widely shared liberal desire for inclusiveness, but because of government fears of civil war in Ireland. By the Acts of Union in 1800, the Irish parliament had been abolished and its representatives sent to join the British parliament in ![]() Westminster. These representatives, mostly drawn from the Anglo-Irish aristocracy, had to be Anglican (members of the Church of England), although Irish Catholics had been eligible to vote since 1793. In 1828, however, the Catholic Association succeeded in promoting the election of Daniel O’Connell, despite his ineligibility as a Roman Catholic to serve in the House of Commons. Fearful of the new powers of the Catholic Association, which threatened British rule in Ireland, parliamentary leaders sought a compromise: to allow Roman Catholic members like O’Connell to sit in Parliament, while outlawing the Association and raising the property qualification to vote in Ireland.

Westminster. These representatives, mostly drawn from the Anglo-Irish aristocracy, had to be Anglican (members of the Church of England), although Irish Catholics had been eligible to vote since 1793. In 1828, however, the Catholic Association succeeded in promoting the election of Daniel O’Connell, despite his ineligibility as a Roman Catholic to serve in the House of Commons. Fearful of the new powers of the Catholic Association, which threatened British rule in Ireland, parliamentary leaders sought a compromise: to allow Roman Catholic members like O’Connell to sit in Parliament, while outlawing the Association and raising the property qualification to vote in Ireland.

The conservative Tory government swiftly passed the Catholic Emancipation Bill, despite its unpopularity with English voters, partly by drawing upon the networks of power and patronage of the borough system. Sir Robert Peel, for example, lost his re-election bid at Oxford in February of 1829 amidst an uproar over the Catholic emancipation bill, which he was sponsoring in the House of Commons. But just in time to introduce the bill, he was nominated and (re-)elected by a total of three voters as a representative for ![]() Westbury, where a notorious borough owner had resigned in his favor.

Westbury, where a notorious borough owner had resigned in his favor.

After the passage of Catholic emancipation, Peel and other government leaders were “subjected to much abuse for ‘ratting’ from their outraged ‘protestant’ followers” (Brock 54). The Dowager Duchess of ![]() Richmond even “decorated her drawing room with stuffed rats named after them and their fellow apostates” (Brock 54). In the aftermath of the act, “anti-Popery” protests in England coalesced around the “rotten” electoral system which had favored Catholic emancipation. Announcing his conversion to Reform in March 1829, for example, the Earl of Winchilsea told the Lords that when he saw “those who were possessed of close boroughs . . . sacrificing their principles, in order that they might be able to patch up fortunes which had been broken and ruined by their vices, he had no hesitation in saying ‘let honest people have the representation which these have so grossly abused’” (Brock 55). Anti-Catholic sentiment thus fueled a new coalition for fundamental parliamentary reform.

Richmond even “decorated her drawing room with stuffed rats named after them and their fellow apostates” (Brock 54). In the aftermath of the act, “anti-Popery” protests in England coalesced around the “rotten” electoral system which had favored Catholic emancipation. Announcing his conversion to Reform in March 1829, for example, the Earl of Winchilsea told the Lords that when he saw “those who were possessed of close boroughs . . . sacrificing their principles, in order that they might be able to patch up fortunes which had been broken and ruined by their vices, he had no hesitation in saying ‘let honest people have the representation which these have so grossly abused’” (Brock 55). Anti-Catholic sentiment thus fueled a new coalition for fundamental parliamentary reform.

Catholic emancipation demonstrated not only how rigged elections enabled ministers to flout public opinion, but also how outside groups like the Catholic Association could nonetheless mobilize voters and demand political concessions. In London as well as ![]() Leicester, advocates for parliamentary reform sought in 1829 to form “a club or committee, resembling the Catholic Association, to take advantage of every favourable opportunity for working Reform” (qtd. in Brock 58). As the Birmingham Political Union for the Protection of Public Rights proclaimed in December of 1829, the “general distress which now afflicts the country” due to the “gross mismanagement of public affairs” could only be “permanently remedied by an effectual Reform in the Commons

Leicester, advocates for parliamentary reform sought in 1829 to form “a club or committee, resembling the Catholic Association, to take advantage of every favourable opportunity for working Reform” (qtd. in Brock 58). As the Birmingham Political Union for the Protection of Public Rights proclaimed in December of 1829, the “general distress which now afflicts the country” due to the “gross mismanagement of public affairs” could only be “permanently remedied by an effectual Reform in the Commons ![]() House of Parliament” (qtd. in Brock 60). Embracing the effort to form a “POLITICAL UNION between the Lower and the Middle Classes of the People,” 12 to 15,000 people attended the Birmingham meeting in January 1830, producing a petition signed by 30,000 [original capitalization] (qtd. in Brock 61).

House of Parliament” (qtd. in Brock 60). Embracing the effort to form a “POLITICAL UNION between the Lower and the Middle Classes of the People,” 12 to 15,000 people attended the Birmingham meeting in January 1830, producing a petition signed by 30,000 [original capitalization] (qtd. in Brock 61).

By 1830, events within and far beyond the halls of government conspired to make parliamentary reform not only possible but urgent. As Lord Russell later recalled, “In the western counties, large bodies of . . . idle young men went about destroying thrashing machines, and setting fire to ricks of hay and stacks of corn. At night, the whole atmosphere was lighted up by fires, the work of lawless depredators . . . and the whole framework of society seemed about to yield to force and anarchy” (53). The rural “Swing” riots appeared to echo the revolutionary events of that year in ![]() France. Leaders of the cosmopolitan Whig party like Lord Charles Grey, who had nearly been tried for treason in 1794 as a “Friend of the People,” took notice (Brock 71). As Grey wrote in a letter of March 1830, “the newspapers in their attacks on landowners have destroyed all respect for rank, station, and institutions of government”; by April, aware that the king was fatally ill, he worried that the state of the kingdom was “too like what took place in France before the Revolution” (qtd. in Brock 69).

France. Leaders of the cosmopolitan Whig party like Lord Charles Grey, who had nearly been tried for treason in 1794 as a “Friend of the People,” took notice (Brock 71). As Grey wrote in a letter of March 1830, “the newspapers in their attacks on landowners have destroyed all respect for rank, station, and institutions of government”; by April, aware that the king was fatally ill, he worried that the state of the kingdom was “too like what took place in France before the Revolution” (qtd. in Brock 69).

In May, Daniel O’Connell, the Irish Catholic M.P., proposed a measure for triennial Parliaments, complete male suffrage, and vote by secret ballot. In response, the Whigs began to circulate their own less radical schemes, with payments to compensate current borough owners. With the death of King George IV in June 1830, William IV ascended to the throne. The new king was neither closely allied with ultra-Tory landowners nor opposed to working with the Whigs. Four days after King George’s death, Charles Grey declared to the Lords that the current Tory government had shown itself “incompetent to manage the business of the country” (qtd. in Brock 72). By law, Parliament had to dissolve within six months of the king’s death; in the resulting election, the Whigs came to power as part of a coalition devoted to reform, with Lord Grey as Prime Minister.

2. “Reform, That You May Preserve”

“And it is a remarkable example of the confusion into which the present age has fallen; of the obliteration of landmarks, the opening of floodgates, and the uprooting of distinction,” says Sir Leicester with stately gloom; “that I have been informed, by Mr. Tulkinghorn, that Mrs. Rouncewell’s son has been invited to go into Parliament. . . . He is called, I believe – an – Ironmaster.”

– Charles Dickens, Bleak House (ch. 28)

When the Whigs took office, almost 2,000 rural “Swing” rioters were awaiting trial. Punishments were severe: 252 people were given capital sentences, 19 were hanged, and about 500 were transported to ![]() Australia (Haywood 211). The successful reform act sponsored by Lord Grey (and carried by Lord Russell) thus sought to forestall threats of revolution. As Lord Macaulay advised Parliament during the debates of 1831: “Reform, that you may preserve” (24).

Australia (Haywood 211). The successful reform act sponsored by Lord Grey (and carried by Lord Russell) thus sought to forestall threats of revolution. As Lord Macaulay advised Parliament during the debates of 1831: “Reform, that you may preserve” (24).

While radicals like O’Connell and William Cobbett pressed for universal suffrage and a secret ballot, the Whigs offered only redistricting and more consistent property qualifications to vote.[8] In so doing, they acknowledged how the landscape of England had shifted. On the one hand, the cities of Manchester, Birmingham and Leeds did not have a single M.P. between them, even as their population approached half a million. On the other hand, eleven seaboard counties, parts of which were falling into the sea, still contained more than half the English borough seats (Brock 17-18). The Reform Act responded to these shifts with a major redistribution of English and Welsh seats in the House of Commons, robbing existing boroughs of more than a hundred members, while adding more than a hundred members for major counties and unrepresented boroughs.[9] In addition, the patchwork of voter eligibility in the boroughs was replaced by a uniform standard: all male householders living in property worth £10 a year were now eligible to vote. To remedy the most egregious practices of paying voters to travel to the polls, the act also introduced a registration system, increased the number of polling places, and shortened the poll to two days. The open ballot system, however, was retained, allowing landowners to continue monitoring the votes of their dependents.

Figure 1: Riots at Bristol by James Catnach, 1831 (used with permission, University of Bristol Library Special Collections)

Newly-elected Members of Parliament in the first reformed parliament included radical journalists like Cobbett and James Silk Buckingham, who represented the newly created borough of ![]() Sheffield. As Buckingham noted in the first issue of his Parliamentary Review and Family Magazine in 1833, “the intense interest manifested by all classes during the progress of Parliamentary Reform, justifies the belief that a corresponding degree of attention will be paid to its first official labours” (“Opening” 1). With this in mind, he promised to “place the reader as nearly as possible in the position of one entering the House himself, and witnessing in person all that is passing around him” (1).

Sheffield. As Buckingham noted in the first issue of his Parliamentary Review and Family Magazine in 1833, “the intense interest manifested by all classes during the progress of Parliamentary Reform, justifies the belief that a corresponding degree of attention will be paid to its first official labours” (“Opening” 1). With this in mind, he promised to “place the reader as nearly as possible in the position of one entering the House himself, and witnessing in person all that is passing around him” (1).

Although readers’ observation of the House through published reports was virtual, it was hardly meant to be passive. Describing the debates of 25 July 1833 on colonial slavery, for example, Buckingham’s radical Parliamentary Review declared that “if the Country submits tamely to be . . . cheated out of that Immediate Emancipation which they demanded, by Petitions signed by 1,500,000 individuals in one single Session . . . then do they deserve to be enslaved themselves for ever” (“House of Commons” 326). After all, “having been made, by the Reform Bill, the entire creators of the House of Commons, and by consequence, the choosers of those who are to make the laws,” the people of England “will deserve universal scorn and contempt if they do not compel, by the overwhelming force of public opinion, all their representatives to perform their duty” (326). Petitioners, including the many who could not yet vote, had become in a manner of speaking the “creators of the House of Commons,” and they were urged to exercise their “overwhelming” power over their representatives.

3. Virtual Representation

For a full appreciation of the advantages of a private seat in the House of Commons let us always go to those great Whig families who were mainly instrumental in carrying the Reform Bill. The house of Omnium had been very great on that occasion. It had given up much, and had retained for family use simply the single seat at Silverbridge. But that that seat should be seriously disputed hardly suggested itself as possible to the mind of any Palliser. The Pallisers and the other great Whig families have been right in this. They have kept in their hands, as rewards for their own services to the country, no more than the country is manifestly willing to give them.

– Anthony Trollope, Can You Forgive Her? (ch. 69)

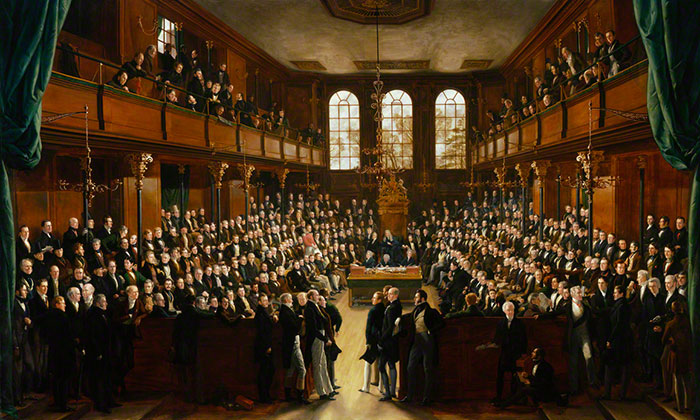

Yet the people were still, in practice, confined to the eaves–literally as well as figuratively. As the Parliamentary Review noted with regard to the House of Commons, “It has no respectable provision for the admission of strangers. It excludes ladies altogether from the pleasure of being witnesses of its proceedings, unless by secreting themselves in a miserably confined spot above the ceiling, called the ventilator” (“Opening” 5). This miserable accommodation might be a useful figure for the limits of the Reform Act of 1832, as it neither enfranchised the majority of British citizens nor rooted out the most common forms of electoral or governmental corruption. The extension of the franchise was modest, as the percentage of the adult male population entitled to vote in England and Wales increased from 13 to 18 percent (Cunningham 162).[12] Widespread disappointment with this limited increase ensured that parliamentary reform would remain a live issue in subsequent decades, with the rise of Chartism (a mass movement promoting universal male suffrage and other electoral reforms in the “People’s Charter”) as well as Liberalism.[13] (See Chris R. Vanden Bossche, “On Chartism.”) As Buckingham complained in the 1840s, “the avowed principle of this Bill was to substitute actual for virtual representation. . . . Yet what is the fact? Why, that out of a collective population of twenty-eight millions of persons in the United Kingdom, the total number of the electoral body . . . is less than a million – or less than one in thirty of the entire population!” (National Evils 436). The gap between actual and virtual representation remained visible and compelling, as families like the house of Omnium in Trollope’s novel held on tight to “a single seat” in the House of Commons, until the Representation of the People Act of 1867 (or the “Second Reform Act”) and subsequent reforms.

Figure 2: The House of Commons, 1833 by Sir George Hayter (used with permission; this portrait is on display and belongs to the Collection of the National Portrait Gallery, London; copyright ©, National Portrait Gallery)

While historians agree that the Reform Act of 1832 did not significantly extend the franchise, they continue to debate what the act did accomplish. Many now contend that the Reform Act successfully shored up the power of the hereditary landowners, as, for example, the strategic concession of additional seats in populous districts consolidated the power of surrounding rural areas and the advocacy of reform reinvigorated the leadership of major Whig landowners. Conceived as a means to salvage the status quo of aristocratic power, the Reform Act may have succeeded better at this task than many had imagined.[14]

Although it was intended by legislators to remedy and reinforce the existing political system, however, the Reform Act did result in some major changes. First of all, as George Macaulay Trevelyan later declared, “the sovereignty of the people had been established in fact, if not in law” (242). The Reform Act was a “turning point in the history of the aristocracy,” as Lawrence James explains, since the events of 1832 had “proved beyond question that the Lords veto could not override the will of the Commons” (274). It also gutted the powerful coalition of corn and West Indian sugar growers, which had depended upon the malapportioned House (Holt 29). As Henry Taylor later recalled, popular support for the abolition of slavery, expressed in petitions to Parliament, had “waxed louder every year,” inspiring a rebellion in ![]() Jamaica. “This terrible event . . . was indirectly a death-blow to slavery. The reform of Parliament was almost simultaneous with it, and might have been sufficient of itself” (1:123). (See Sarah Winter, “On the Morant Bay Rebellion in Jamaica and the Governor Eyre-George William Gordon Controversy, 1865-70.”) Furthermore, as John Phillips and Charles Wetherell have shown, the frenzy over Reform “unleashed a wave of political modernization” which “destroyed the political system that had prevailed during the long reign of George III and replaced it with an essentially modern electoral system based on rigid partisanship and clearly articulated political principles” (412).

Jamaica. “This terrible event . . . was indirectly a death-blow to slavery. The reform of Parliament was almost simultaneous with it, and might have been sufficient of itself” (1:123). (See Sarah Winter, “On the Morant Bay Rebellion in Jamaica and the Governor Eyre-George William Gordon Controversy, 1865-70.”) Furthermore, as John Phillips and Charles Wetherell have shown, the frenzy over Reform “unleashed a wave of political modernization” which “destroyed the political system that had prevailed during the long reign of George III and replaced it with an essentially modern electoral system based on rigid partisanship and clearly articulated political principles” (412).

Even as it shored up aristocratic power, paradoxically, the Reform Act of 1832 altered the political landscape in fundamental ways by establishing new channels between members of Parliament and their fellow-subjects. In particular, the Reform Act of 1832 launched the so-called Age of Reform, in which parliament undertook a broad review of institutions affecting the lives of “the people”–particularly those who could not vote. As Peter Mandler has argued, this reform movement affected the disenfranchised more than it did the enfranchised. With the proliferation of political journalism and petitions, the “aristocratic coquetting with outdoor forces” under Whig leadership produced a “chain of agitations” in which Parliament became “the national cynosure, the center of a whirlpool of demands and pressures from without” (Mandler 2). The ensuing decades of reform witnessed “an appeal to Parliament to reconnect itself to the people, not only by enfranchising them but also by protecting them, by legislating for them” (Mandler 2). With this in mind, the reformed parliament quickly undertook to examine factory working hours and pauper institutions, along with colonial slavery. Even Sir Robert Peel declared his “willingness to adopt and enforce” the “spirit of the Reform Bill” as a “rule of government” through the “careful review of institutions” and the “correction of proved abuses and the redress of real grievances,” while decrying the “perpetual vortex of agitation” in which “public men can only support themselves in public estimation by adopting every popular impression of the day” (qtd. in Brantlinger 4-5).

In this sense, the Tory Charles Greville was right to note in 1833 that “the public appetite for discussion and legislation has been whetted and is insatiable,” even as he exaggerated the consequences, fearing that “Reform in Parliament . . . has opened a door to anything” (qtd. in Mandler 151). The partial opening afforded by this event would reverberate in the British national imagination for many decades to come.

HOW TO CITE THIS BRANCH ENTRY (MLA format)

published March 2013

Berman, Carolyn Vellenga. “On the Reform Act of 1832.” BRANCH: Britain, Representation and Nineteenth-Century History. Ed. Dino Franco Felluga. Extension of Romanticism and Victorianism on the Net. Web. [Here, add your last date of access to BRANCH].

WORKS CITED

Bentham, Jeremy. Plan of Parliamentary Reform in the Form of a Catechism. 1817. London: Wooler, 1818. Gale, Cengage Learning. Web. 21 March 2012.

Brantlinger, Patrick. The Spirit of Reform: British Literature and Politics, 1832-1867. Cambridge, MA: Harvard UP, 1977. Print.

Brock, Michael. The Great Reform Act. London: Hutchinson, 1973. Print.

Buckingham, James Silk. National Evils and Practical Remedies, With the Plan of Model Town. London: Jackson, 1849. Rpt. Clifton, NJ: Kelley, 1973. Print.

Cannon, John. Parliamentary Reform 1640-1832. London: Cambridge UP, 1973. Print.

Chafetz, Joshua. Democracy’s Privileged Few: Legislative Privilege and Democratic Norms in the British and American Constitutions. New Haven: Yale UP, 2007. Print.

Cunningham, Hugh. “Dickens as a Reformer.” A Companion to Charles Dickens. Ed. David Paroissien. Malden, MA: Blackwell, 2008. 159-73. Print.

Drew, John M. L. Dickens the Journalist. Houndmills, Basingstoke/New York: Palgrave, 2003. Print.

Gratton, Charles J. The Gallery, a Sketch of the History of Parliamentary Reporting and Reporters. London, Bath, 1860. Print.

Hadley, Elaine. “On Opinion Politics and the Ballot Act of 1872.” BRANCH: Britain, Representation and Nineteenth-Century History. Ed. Dino Franco Felluga. Extension of Romanticism and Victorianism on the Net. Web. 15 December 2012.

Haywood, Ian. Bloody Romanticism: Spectacular Violence and the Politics of Representation, 1776-1832. Houndmills, Basingstoke/New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2006. Print.

Hilton, Boyd. A Mad, Bad, and Dangerous People? England, 1783-1846. Oxford: Clarendon, 2006. Print.

Holt, Thomas. The Problem of Freedom: Race, Labor and Politics in Jamaica and Britain, 1832-1938. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins P, 1992. Print.

“House of Commons–July 25.” The Parliamentary Review, and Family Magazine. Ed. J. S. Buckingham, Esq. M.P. 3.6 (1833): 322-33. Microform.

James, Lawrence. Aristocrats: Power, Grace, and Decadence: Britain’s Great Ruling Classes from 1066 to the Present. New York: St. Martin’s, 2009. Print.

Macaulay, Thomas Babington. “Parliamentary Reform.” Speech delivered 2 March 1831. Selected Writings. Ed. John Clive and Thomas Pinney. Chicago: U of Chicago P, 1972. 165-180. Print.

Mandler, Peter. Aristocratic Government in the Age of Reform: Whigs and Liberals, 1830-1852. Oxford: Clarendon, 1990. Print.

“Opening of the First Session of the First Reformed Parliament.” The Parliamentary Review and Family Magazine. Ed. J. S. Buckingham, J.S., Esq. M.P. 1.1 (February 1833): 1-29. Microform.

Parry, Jonathan P. The Rise and Fall of Liberal Government in Victorian Britain. New Haven: Yale UP, 1993. Print.

Phillips, John A. and Charles Wetherell. “The Great Reform Act of 1832 and the Political Modernization of England.” American Historical Review 100.2 (April 1995): 411-36. Web. 18 Nov. 2011.

Pitkin, Hanna Fenichel. The Concept of Representation. Berkeley: U of California P, 1967. Print.

Russell, John [Earl]. Recollections and Suggestions, 1813-1873 . Boston: Roberts Brothers, 1875. Print.

Taylor, Henry. Autobiography of Henry Taylor, 1800-1875. 2 vols. London: Longmans, Green, 1885. Print.

Thackeray, William Makepeace. Vanity Fair. 1847-48. Ed. Peter L. Shillingsburg. ew York/London: Norton, 1994. Print.

Thompson, William. Appeal of One-Half The Human Race, Women, against the Pretensions of the Other Half, Men, to Retain Them in Political and Thence in Civil and Domestic Slavery; in Reply to a Paragraph of Mr. Mill’s Celebrated “Article on Government”. London: Longman, 1825. Rpt. New York: Source Book, 1970. Print.

Trevelyan, George Macaulay. British History in the Nineteenth Century and After (1782-1919). 1922. London: Longmans, 1947. Print.

Trollope, Anthony. Can You Forgive Her?. 1864-65. Oxford/New York: Oxford UP, 2008. Print.

Vanden Bossche, Chris R. “On Chartism.” BRANCH: Britain, Representation and Nineteenth-Century History. Ed. Dino Franco Felluga. Extension of Romanticism and Victorianism on the Net. Web. 17 June 2012.

Vernon, James. Politics and the People: A Study in English Political Culture, c. 1815-1867. Cambridge: Cambridge UP, 1993.

RELATED BRANCH ARTICLES

Janice Carlisle, “On the Second Reform Act, 1867″

Elaine Hadley, “On Opinion Politics and the Ballot Act of 1872″

ENDNOTES

[1] It did so in tandem with similar acts for Scotland and Ireland; for the sake of simplicity, this essay focuses on the passage of the English legislation.

[2] The 1771 clash between a London mob and Parliament involved the imprisonment by the House of printers for their publishing of parliamentary debates concerning the contested election of John Wilkes. The 1810 riots protested the House’s imprisonment of Sir Francis Burdett, M.P. and founder of the Society of the Friends of the People as well as a radical advocate of universal suffrage and the secret ballot, for publishing details of House debates concerning the reporting of debates (Gratton 31-34; 73).

[3] In 1812, Cobbett sold his Parliamentary Debates, a supplement to the weekly Political Register, to the printer Thomas Curson Hansard, who renamed it Hansard’s Parliamentary Debates. Although he was related by family ties to the publishers of the official Parliamentary Papers, T. C. Hansard’s monthly digest did not become an official parliamentary publication until the 1870s.

[4] Hereditary membership in the House of Lords was not abolished until 1999.

[5] “Everyone has heard of what Camelford cost the Marquess of Cleveland till the arrangement with the Marquess of Hertford. The Members who were returned for the marquess paid the voters in ₤1 notes enclosed in a deal box marked ‘China’” (Morning Chronicle 26 July 1830, qtd. in Brock 26).

[6] “Part of an English nobleman’s estates and ‘interest’ might lie in Ireland; or an Englishman might hire an Irish borough seat. Peel was given the seat at Cashel (Tipperary) by his father as a twenty-first birthday present” (Brock 33).

[7] Whig Prime Minister William Pitt had called borough representation (as opposed to counties) “the rotten part of our Constitution” in the 1760s; he and his son William Pitt the Younger failed in their efforts to diminish the power of boroughs by giving more members to counties.

[8] By “universal suffrage,” Cobbett meant male suffrage (Brock 347n101), but some advocates of reform in previous decades had made the case for women’s voting rights as well; see Bentham and Thompson. Sir Frances Burdett’s resolution for universal male suffrage and a secret ballot attracted very little support in 1817-18. The Act of 1832 specified voting rights for “male persons” only; women gained limited voting rights in 1918 and equal franchise in 1928.

[9] As Elaine Hadley notes, this legislation “did not privilege the individual or even populations but aimed to address emergent economic interests, such as the ‘cotton interest’ in ![]() Lancashire” (2); see her BRANCH essay for an analysis of the emergence of “opinion politics” in subsequent decades.

Lancashire” (2); see her BRANCH essay for an analysis of the emergence of “opinion politics” in subsequent decades.

[10] See Haywood 210-222 for descriptions and images of these riots.

[11] Phillips and Wetherell offer a concise summary of these events (412-13). For a full account, see Brock and Cannon.

[12] According to Phillips and Wetherell, the “best-informed” estimates suggest more than 400,000 Englishmen held “a franchise of some sort” before the Reform of 1832, compared to 650,000 afterward (413-14).

[13] See Chris Vanden Bossche’s BRANCH essay for a complete analysis of Chartism.

[14] See Hilton, Mandler, Parry, and Vernon on the aftermath of this Act.