Abstract

The increasing demographic imbalance between men and women in Britain in the nineteenth century forced many women and girls from the middle classes to seek employment to maintain themselves because, in the words of one commentator, “there were not enough husbands to go round.” Working for pay, however, was considered déclassé and the employments that emerged as two of the most popular for middle-class women, nursing and typewriting, had to overcome cultural resistance.

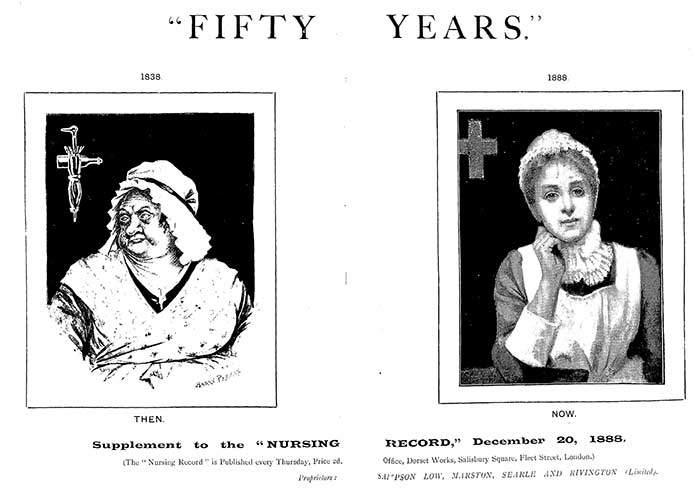

Between 1838 and 1888, nursing had been transformed from a menial job into a respected profession and the popular image of the nurse had evolved from Sairey Gamp to the new-style lady nurse.

In 1859, an article appeared in the Edinburgh Review that shook the foundations of Victorian precepts of genteel womanhood and woman’s place in society. “Female Industry,” by the redoubtable Harriet Martineau, did not immediately topple the edifice of middle-class Victorian patriarchy and propriety, but its influence began the process of undermining the fixed assumptions about women and their role in society. In her article, Martineau asserted the unthinkable—women in the middle and upper classes of British society must have the opportunity to be employed, that is, to work outside the domestic realm and receive wages. Martineau’s position was not entirely new; indeed, “Female Industry” is a review article that summarizes ten reports and books on women and work that had been published between 1843 and 1858.[1] “Female Industry” was nevertheless a major catalyst to subsequent attempts in the nineteenth century to end the disbarment of women from full access to employment and financial independence.

The critical point raised in Martineau’s article, and the one recognized as being the most urgent, was the increasing numerical imbalance between men and women in Britain, tracked by the successive decennial census reports that began in 1801. Martineau’s analysis focused on the 1841 and 1851 census reports, but the 1861 census showed no reversal of the disturbing demographic trend, a phenomenon that, as Honnor Morten observed in 1899, would challenge the values and assumptions espoused by the English middle classes. “[T]he theory was,” according to Morten, “that all women of the richer classes should be wives, and work only on the domestic hearth; . . . . But this every-woman-a-wife theory received a rude shock when the figures of the 1861 census were published, for they showed 2 ½ millions of unmarried women, and demonstrated empathically that, so far as England was concerned, there were not enough husbands to go round” (131). With not enough husbands, women were left unattached and termed “redundant” or “odd women”—“no making a pair with them,” as Rhoda Nunn observes in George Gissing’s 1893 novel, The Odd Women (64).

The gender imbalance was not specific to any single social class, but it was particularly problematic for women in the middle classes, whose access to employment was severely limited and whose families might not be affluent enough to maintain them in comfort for life if they remained unmarried. An unmarried woman with any claims to gentility that she wished to maintain had very few options in life, none of which were attractive. She could become a governess or a paid companion, or she should live with family members, if they could afford to keep her. All these options placed her in a subservient or dependent position in someone else’s household, and none promised a secure future. These factors led to activism for and by middle-class women to secure suitable employment options and education that would prepare them to be more productive and engaged participants in both the public and private spheres. Articles in the periodical press throughout the Victorian period repeatedly addressed the pressing issue of employment and better education for middle-class women, although perhaps the most telling evidence for the personal and cultural anxiety over the need for employment opportunities are the number of letters that appeared in newspapers and in the women’s press from young women and their parents, worried about what options they might have to secure their futures.

The major constraints on efforts to find suitable work for middle-class women were the social and cultural restrictions inherent in Victorian notions of respectability and femininity. But, given the economic and demographic realities of the time, women, as the English Woman’s Journal asserted in 1858, were going to have to work, and “work as they . . . [had] not done yet” (364). Articles in the media about women and work advocated a broad range of possibilities, from the entirely genteel, such as china painting, to the physically and organizationally demanding, such as running a dairy farm. Many of these suggestions were impractical, either because they would not provide a sufficient income or because they required specialized knowledge and other resources that most young women would not have (Young, “Professionalism” 201.). Ultimately, the three areas of work that had the most promise for young middle-class women in the second half of the nineteenth century were teaching, nursing, and typewriting—all jobs that were the principal areas of work for respectable young women throughout the twentieth century. All these areas of work were expanding in the nineteenth century, but only teaching carried with it the aura of both femininity and propriety essential to respectable employment for middle-class women. Teaching in schools was a logical extension of governessing, and while the opening up of board schools in the 1870s did lower the prestige of teaching to some extent, it also opened up many more opportunities for women.

Nursing, by contrast with teaching, was regarded as menial, rough work. At mid-century, the iconic figure of the nurse was the disreputable and gin-sodden Sairey Gamp, from Charles Dickens’s Martin Chuzzlewit (1843-44). The physical intimacy and strenuousness of nursing duties, the need to handle bodily fluids, and the kind of knowledge of human anatomy acquired in those duties made nursing a job that was considered degrading, the lowest form of domestic service. By around mid-century, however, there were several initiatives to change both nursing and cultural attitudes towards nursing. The first was the establishment of protestant nursing sisterhoods in England in the 1840s and 1850s. The sisterhoods comprised affluent young women, who paid a premium to enter and acquire nursing skills as lady probationers, and non-paying working-class women, who were trained to carry out basic nursing care under the direction of the Sisters (Moore 3-4). The sisterhoods initially provided domiciliary nursing for the poor, but some of the larger nursing sisterhoods, notably ![]() St. John’s House, eventually contracted to provide all nursing services in the teaching hospitals in which their members trained. These contracts were eventually terminated over financial disputes and teaching hospitals founded their own training schools later in the century, but the sisterhoods pioneered the model for systemized, professional training that ultimately established nursing as an acceptable area of employment for middle-class women (Helmstadter and Godden 170-78).

St. John’s House, eventually contracted to provide all nursing services in the teaching hospitals in which their members trained. These contracts were eventually terminated over financial disputes and teaching hospitals founded their own training schools later in the century, but the sisterhoods pioneered the model for systemized, professional training that ultimately established nursing as an acceptable area of employment for middle-class women (Helmstadter and Godden 170-78).

That the genteel Sisters’ work was unpaid invested it with the aura of philanthropy and respectability. Nursing’s public standing was further enhanced by Florence Nightingale’s mission to ![]() Scutari during the Crimean War. The nurses who traveled to the Crimea in 1854 totaled 217 (some under the supervision of Mary Stanley), nine of whom were Anglican Sisters, twenty-eight Catholic Sisters, and fifty unaffiliated ladies (Helmstadter and Godden 89). The 128 working-class nurses outnumbered the lady nurses, but the publicity surrounding the Crimean nursing mission focused on the ladies and on their courage in facing hardship and danger in a remote foreign territory in order to bring comfort and care to wounded soldiers. Almost overnight, Nightingale, a lady of impeccable social credentials, replaced Sairey Gamp as the popular image of the nurse.

Scutari during the Crimean War. The nurses who traveled to the Crimea in 1854 totaled 217 (some under the supervision of Mary Stanley), nine of whom were Anglican Sisters, twenty-eight Catholic Sisters, and fifty unaffiliated ladies (Helmstadter and Godden 89). The 128 working-class nurses outnumbered the lady nurses, but the publicity surrounding the Crimean nursing mission focused on the ladies and on their courage in facing hardship and danger in a remote foreign territory in order to bring comfort and care to wounded soldiers. Almost overnight, Nightingale, a lady of impeccable social credentials, replaced Sairey Gamp as the popular image of the nurse.

The philanthropic work of Anglican Sisters and Nightingale’s highly publicized mission to Scutari raised the public profile of the lady nurse but did not promote nursing as paid employment for women. The sisterhoods provided a secure and stable home base for their members, limiting the women’s exposure to the challenges of independent living. Sisters worked and were guaranteed room and board for life, but they did not receive salaries. Not all women who received nursing instruction from the sisterhoods became members, however, and lay graduates could seek employment elsewhere. As more women were trained by the sisterhoods and in the Nightingale School of Nursing established at ![]() St. Thomas’s Hospital in 1860, professionalized lady nurses became available to work in hospitals throughout Britain. The women who entered the training schools as lady probationers often went on to supervisory positions in hospitals throughout the country, indeed often founding training programs for more new nurses (Abel-Smith 23-4). These new-style supervisors and nurses worked for pay, and while the cultural antipathy to the idea of women of the middle and upper classes working for money persisted, wage-earning genteel lady nurses proliferated.

St. Thomas’s Hospital in 1860, professionalized lady nurses became available to work in hospitals throughout Britain. The women who entered the training schools as lady probationers often went on to supervisory positions in hospitals throughout the country, indeed often founding training programs for more new nurses (Abel-Smith 23-4). These new-style supervisors and nurses worked for pay, and while the cultural antipathy to the idea of women of the middle and upper classes working for money persisted, wage-earning genteel lady nurses proliferated.

While the popular perception of the contrast between the old-style nurse and the new-style nurse remained a contrast between Sairey Gamp and Florence Nightingale, neither of these figures was in fact an accurate representation of these nursing types. The old-style nurse was usually a competent woman from the upper reaches of the working classes who had worked on a hospital ward for many years—often decades—and who had learned her skills on the job, often under the supervision of the physician or surgeon treating the patients on that ward (Young, “‘Entirely a Woman’s Question?’” 26-7). The knowledge acquired by these women was accordingly specialized. Doctors in the major hospitals favored retaining these nurses, whom they had trained and whom they knew and trusted. The new-style nurse was trained by nursing matrons and sisters (nursing sisters, as opposed to religious Sisters who were nurses, were the head nurses on the wards). The trainee nurses rotated through the various wards in the hospital, receiving education in all areas of nursing care and medical and surgical treatment. This model of training, originated by the sisterhoods and followed by the Nightingale School, became the standard method for nursing education throughout the world for the next 150 years (Helmstadter and Godden 188-9). While nursing education today is commonly carried out in universities and community colleges, the rotation of students through different areas of specialization is still the norm.

Within a few decades, nursing reformers had transformed nursing from a menial job into a respected profession, although there were gradations within the ranks, ranging from matrons and ward sisters (i.e., head nurses), to staff nurses in major teaching hospitals, to private duty nurses. Nursing in provincial cottage hospitals, district nursing, and midwifery carried less prestige. The status of nursing was greatly enhanced by the establishment of the British Nursing Association in 1887, with Queen Victoria’s third daughter, the Princess Christian, as its first president. In 1888, the Nursing Record began publication (continuing as the Nursing Record and Hospital World in 1893 and the British Journal of Nursing in 1902). The December Supplement to the Nursing Record’s first volume celebrated the transformation of the British nurse in the fifty years since the appearance of Sairey Gamp in 1838 with a reproduction of an illustration of the imaginary Sairey juxtaposed with a picture of an idealized new-style nurse. This image of the new-style nurse—young, attractive, and smartly attired in the dark gown and white apron and cap that had become the standard uniform—was perhaps as imaginary as Sairey, but she nevertheless represented a perception of the nurse as well-groomed and professional, or, in other words, as respectable. By this time, nursing had become one of the most popular occupations for middle-class ladies and its status was underwritten by royal endorsement when the BNA received a royal charter in 1893, becoming the Royal British Nursing Association (Abel-Smith 72). A number of prominent late-Victorian women writers and activists, including George Egerton, Margaret Harkness, Mary Kingsley, and Laura Ormiston Chant, trained and worked as hospital nurses before moving on to other careers—although Chant’s family, like many others at the time, resisted their daughter’s entry into the nursing profession (Brown et al).

In order to become work that was culturally acceptable for women in the middle classes, nursing had to overcome its own history. Typing, by contrast, was an entirely new form of occupation in the late-Victorian period. Prototypes of writing machines appeared as early as the 1830s, but the typewriter, in the form in which it was to become the most transformative business machine of the century, was first produced in ![]() New York by the Remington company in 1874 (Davies 33-35). (See Christopher Keep, “The Introduction of the Sholes & Glidden Type-Writer, 1874.″) The inventor of the Remington model, Christopher Latham Sholes, coined the term “typewriter,” which was subsequently used throughout the nineteenth century to refer both to the machines and to their operators. By the early 1880s, typewriters were becoming commonplace in government and business offices across Britain. Although men were some of the first typewriters, women soon dominated the field of typing, which provided them with an entrée into areas of work in the civil service and business that had hitherto been severely restricted, if not entirely closed.

New York by the Remington company in 1874 (Davies 33-35). (See Christopher Keep, “The Introduction of the Sholes & Glidden Type-Writer, 1874.″) The inventor of the Remington model, Christopher Latham Sholes, coined the term “typewriter,” which was subsequently used throughout the nineteenth century to refer both to the machines and to their operators. By the early 1880s, typewriters were becoming commonplace in government and business offices across Britain. Although men were some of the first typewriters, women soon dominated the field of typing, which provided them with an entrée into areas of work in the civil service and business that had hitherto been severely restricted, if not entirely closed.

The challenges that typewriting presented to Victorian sensibilities were quite different from those presented by nursing, which at least conformed to assumptions about women’s place as nurturers and care-givers. At the same time, however, typewriting did not, like nursing, have unsavory associations with menial labor and physical intimacy. As an entirely new occupation, it had few associations with anything except office work, which had been gradually opening up to educated middle-class women for more than a decade. Typewriting multiplied opportunities for women as government and business recognized the typewriter’s potential for increasing efficiency, a growing need as the service sector expanded to meet the demands of market capitalism. The rapid expansion of typewriting as an employment for women caused anxiety within Victorian culture because it drew more and more women into the public spheres of commerce and civil service. Previously, the small numbers of women in offices ensured a level of insulation from overt exposure in commercial and other public venues. Women in the civil service were indeed segregated, working in spaces separate from their male counterparts, even entering the workplace through a separate entrance (Zimmeck 159-60). This level of segregation became impracticable as the number of women working in offices increased.

Typewriting offered more than just employment opportunities for women in the 1880s and 1890s; it offered entrepreneurial options as well. Typewriting offices and training schools, owned and operated by enterprising middle-class women, opened up in cities and municipalities all over England in the 1880s and 1890s. Marion Marshall, one of the first and most far-sighted of these women, established offices in London and ![]() Cambridge that provided specialized typing services to members of professions such as law and medicine. Not only could Mrs. Marshall guarantee that women in her employ would be well-educated and would have excellent technical skills but, in her office in Cambridge which catered to university professors, she could also offer operators who could transcribe both Latin and Greek texts, having acquired machines that typed the Greek alphabet (Young, “Ladies and Professionalism” 203-5).

Cambridge that provided specialized typing services to members of professions such as law and medicine. Not only could Mrs. Marshall guarantee that women in her employ would be well-educated and would have excellent technical skills but, in her office in Cambridge which catered to university professors, she could also offer operators who could transcribe both Latin and Greek texts, having acquired machines that typed the Greek alphabet (Young, “Ladies and Professionalism” 203-5).

Early media discussions of typewriting as a new area of employment for women stressed the need for high levels of general knowledge, impeccable skills in writing and grammar, and fluency in at least one foreign language (usually German and/or French). Typewriting accordingly seemed like an ideal employment option for educated women of the middle classes. Advocates of women’s employment rights maintained that typewriters should ideally have university-level education as well as technical training in typing skills (Young, “Ladies and Professionalism” 205-6). Employers saw things differently, however. As the demand for typewriters grew in both government and industry, more and more women acquired basic typing skills and flooded the labor market. Employers then, as now, were eager to take advantage of the opportunity to hire semi-skilled workers at a lower wage, and typewriting lost much of its drawing power as a potentially satisfying and remunerative career.

Typewriting nevertheless retained its appeal for many young women of the period. Its attractions were manifold. Typing skills could be acquired relatively quickly and inexpensively (there were many cheap and nasty versions of instruction). Typewriting was thoroughly modern, associated with a new technology that most people at the time found mystifying.[2] Most typewriting jobs were offered in urban centers, providing young women with the excitement of independent life in a city. As a result of these factors, typewriting acquired an aura of youth and glamour, and the lady typewriter evolved into the typewriter-girl, the quintessential late-Victorian young working woman who represented modernity and female independence. The typewriter-girl was celebrated in stories, verse, and song, usually as the love interest. She also featured in jokes and in music hall sketches where the double meaning of “typewriter” was exploited, the standard gag being a man telling his wife that he was working late with his typewriter on his knee. Other fictional versions of the typewriter interpreted her skill and technical know-how as indications of her capability and turned her into an amateur sleuth (e.g., Grant Allen’s The Type-writer Girl, 1897, and Tom Gallon’s The Girl Behind the Keys, 1903). This general cultural perception of the late-Victorian typewriter-girl was positive, if somewhat down-market from the original idea of the lady typewriter, but the real experience of young women working in late-Victorian offices was often bleak, with young women struggling with low wages and poor working and living conditions.

Images of typewriters from the late nineteenth century remained predominantly glamorous, however, and the most lasting representation of Victorian typewriters is arguably the self-possessed young women in Mary Barfoot’s typewriting school in The Odd Women. The main focus of the novel is on the personal lives of the main characters, but some of the minor characters who are students in the school, notably Winnifred Haven and Milly Vesper, are presented as intelligent, accomplished, and hopeful for a future as independent working women. It is Monica Madden’s decision to leave the school and make an unsuitable marriage for the sake of financial security, not the typewriter-girls’ entrance into the world of commerce, that leads to misery. For women in late-Victorian England, the promise of independence that employment entailed, it would seem, was too great a lure to be countered by the realities of the demanding physical labor of nursing or the financial precariousness of typewriter.

published March 2015

HOW TO CITE THIS BRANCH ENTRY (MLA format)

Young, Arlene. “The Rise of the Victorian Working Lady: The New-Style Nurse and the Typewriter, 1840-1900.” BRANCH: Britain, Representation and Nineteenth-Century History. Ed. Dino Franco Felluga. Extension of Romanticism and Victorianism on the Net. Web. [Here, add your last date of access to BRANCH].

WORKS CITED

Abel-Smith, Brian. A History of the Nursing Profession. London: Heinemann, 1960. Print.

Brown, Susan, Patricia Clements, and Isobel Grundy, eds. “Laura Ormiston Chant entry: Life screen.” Orlando: Women’s Writing in the British Isles from the Beginnings to the Present. Cambridge: Cambridge UP, 2006. Web. 05 December 2014.

Davies, Margery W. A Woman’s Place Is at the Typewriter: Office Work and Office Workers, 1870-1930. Philadelphia: Temple UP, 1982. Print.

English Woman’s Journal 1 (August 1858): 361-7. Print.

Gissing, George. The Odd Women. Ed. Arlene Young. Peterborough: Broadview Press, 1998. Print.

Helmstadter, Carol and Judith Godden. Nursing before Nightingale, 1815-1899. Burlington: Ashgate, 2011. Print.

Moore, Judith. A Zeal for Responsibility: The Struggle for Professional Nursing in Victorian England, 1868-1883. Athens: U of Georgia P, 1988. Print.

Morten, Honnor. “Questions for Women IV: Woman’s Invasion of Men’s Occupations.” Queen 28 Jan. 1899: 131, 134. Print.

Young, Arlene. “Entirely a woman’s question?”: Class, Gender, and the Victorian Nurse. Journal of Victorian Culture 13:1 (Spring 2008): 18-41. Print.

—. “Ladies and Professionalism: The Evolution of the Idea of Work in the Queen, 1861-1900.” Victorian Periodicals Review 40:3 (Fall 2007): 189-215. Print.

Zimmeck, Meta. “Jobs for the Girls: the Expansion of Clerical Work for Women, 1850-1914.” Unequal Opportunities: Women’s Employment in England 1850-1918. Ed. Angela V. John. Oxford: Blackwell, 1986. 153-77. Print.

FURTHER READING

Anderson, Gregory ed. The white-Blouse Revolution: Female Office Workers since 1870. Manchester: Manchester UP, 1988.

Holcombe, Lee. Victorian Ladies at Work: Middle-Class Working Women in England and Wales 1850-1914. Hamden: Archon, 1973.

Keep, Christopher. “The Cultural Work of the Type-Writer Girl,” Victorian Studies 40:3 (1997): 401-26.

Liggins, Emma. George Gissing, the Working Woman, and Urban Culture. Burlington: Ashgate, 2006.

Summers, Anne. “The Mysterious Demise of Sarah Gamp: The Domiciliary Nurse and her Detractors c. 1830-1860.” Victorian Studies 32:3 (1989): 365-86.

Vicinus, Martha. Independent Women: Work and Community for Single Women, 1850-1920. Chicago: U of Chicago P, 1985.

Young, Arlene. “Bachelor Girls and Working Women: Women and Independence in Oliphant, Levy, Allen, and Gissing.” Culture, Class and Gender in the Victorian Novel: Gentlemen, Gent, and Working Women. Houndmills and New York: Macmillan and St. Martin’s, 1999. 119-156.

Endnote:

ENDNOTES

[1] The ten reports and books to which Martineau responds in her article are The Results of the Census of Great Britain in 1851, by Edward Cheshire, 1853; Report of Assistant Poor-law Commissioners on the Employment of Women and Children in Agriculture, 1843; Minutes of the Committee of Council of Education, 1855-6; Reports of the Governesses’ Benevolent Institution, [n.d.]; The Industrial and Social Position of Women in the Middle and Lower Ranks, 1857; Women and Work, by B.L. Smith (Mrs. Bodichon), 1857; Two Letters on Girls’ Schools, and on the Training of Working Women, by Mrs. Austin, 1857; Experience of Factory Life, by M. M., 1857; The Lowell Offering, [n.d.]; and The Laws of Life, with Special Reference to the Physical Education of Girls, by Elizabeth Blackwell. 1858.

[2] The mystifying character of typewriters for the general public is reflected in their association with the supernatural in late nineteenth-century stories and novels—e.g., “Mr Twistleton’s Type-Writer,” Cornhill Magazine (1887), John Kendrick Bang’s The Enchanted Type-Writer (1899), and Tom Gallon’s “The Spirit of Sarah Keech” in The Girl Behind the Keys (1903).