Abstract

This essay discusses the rest cure, a popular treatment for nervous illness pioneered by Philadelphia neurologist Silas Weir Mitchell in the 1860s and ‘70s. Emphasis will be placed on the spread of the cure to Britain and the role of the rest cure in literature.

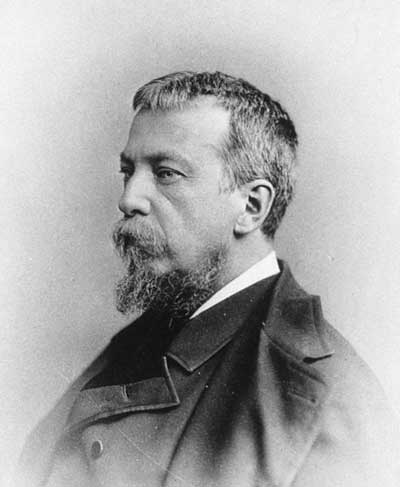

The treatment that the narrator dreads is neurologist Silas Weir Mitchell’s regimen of enforced bed rest, isolation, force-feeding, and massage. Gilman herself (Fig. 1) had experienced the rest cure while under Mitchell’s care in the spring of 1887. Suffering from acute depression after the birth of her daughter, Gilman traveled to ![]() Philadelphia to see the doctor then regarded as “the greatest nerve specialist in the country” (Gilman, The Living of Charlotte Perkins Gilman 95). (See Fig. 2.) Mitchell diagnosed her with hysteria and began his usual treatments.

Philadelphia to see the doctor then regarded as “the greatest nerve specialist in the country” (Gilman, The Living of Charlotte Perkins Gilman 95). (See Fig. 2.) Mitchell diagnosed her with hysteria and began his usual treatments.

I was put to bed, and kept there. I was fed, bathed, rubbed, and responded with the vigorous body of twenty-six. As far as he could see there was nothing the matter with me, so after a month of this agreeable treatment he sent me home with this prescription:

“Live as domestic a life as possible. Have your child with you all the time. . . . Lie down an hour after each meal. Have but two hours’ intellectual life a day. And never touch pen, brush, or pencil as long as you live.” (96)

After faithfully following this “prescription” for months, Gilman wrote, she “came perilously near to losing my mind. The mental agony grew so unbearable that I would sit blankly moving my head from side to side” (96).

Gilman’s autobiography and short story paint a vivid picture of what the rest cure may have been like for some nineteenth-century women. She depicts Mitchell as a medical villain, and the rest cure as a Gothic torture. But it is important to take Gilman’s perspective with a grain of salt. In her essay “Why I Wrote the Yellow Wallpaper?” (1913), Gilman reminds readers that the short story contains “embellishments and additions” to her own personal experiences. Unlike the narrator of “The Yellow Wall-paper,” for instance, Gilman “never had hallucinations or objections to my mural decorations” (86). Gilman’s autobiography, meanwhile, was written decades after her experience of the rest cure, leaving open the possibility that she misremembered aspects of her treatment or exaggerated them for polemical purposes.[1]

Nonetheless, Gilman’s account of Mitchell as medical misogynist has persisted in the popular imagination and colored modern perceptions of the rest cure, some think unfairly. Mitchell worked with countless patients, both male and female, many of whom claimed to benefit from his treatment. While some, such as Gilman, found the rest cure unbearable, others lauded Mitchell’s authoritative demeanor and strictly regimented care. A patient’s response to the rest cure depended on many factors, including his or her socioeconomic level, diagnosis, and temperament. Gilman’s negative response to Mitchell, for instance, may have had something to do with her diagnosis as a hysteric, a class of patients to whom Mitchell was notoriously unsympathetic (Davis 97-98).

This essay will provide a more balanced perspective on the rest cure by drawing on multiple patient accounts, in addition to Mitchell’s own writing on nervous disease. It will also place Mitchell’s treatment in historical context by detailing its origins and eventual migration to foreign soil. While the rest cure is today associated with nervous women, it actually began as a treatment for injured veterans during the Civil War. When Mitchell began his private practice, he repurposed the cure as a treatment for nervous invalids of both sexes. The rest cure quickly gained adherents in the United States and abroad. British gynecologist Dr. William Smoult Playfair imported the rest cure to Britain in 1881, where it was used to treat author Virginia Woolf, among others (Marland 120). Mitchell’s work also reached beyond the English-speaking world. His treatise on the rest cure, Fat and Blood: and How to Make Them (1877), had been translated into four other languages by the time of its author’s death in 1914 (Poirier 15). This essay will touch on all of these points, particularly the spread of the treatment in Britain and the role of the rest cure in literature.

But first, we must go back to the cure’s origins in Civil-War-era Philadelphia. Mitchell first described the rest cure in 1873, when discussing his successful treatment of a case of locomotor ataxia (Poirier 17). The rest cure gained a much wider acceptance with the publication of Mitchell’s Fat and Blood, the first book-length description of his new therapy. Mitchell continued to write about this treatment in later works such as Lectures on Diseases of the Nervous System, Especially in Women (1881) and Doctor and Patient (1887). In his spare time, Mitchell penned successful novels with hysterical female characters, including Roland Blake (1886), Constance Trescot (1905), and Westways (1913). While these works devote attention to nervous women, Mitchell’s guinea pigs for this new treatment were young men.

During the Civil War, Mitchell served as a contract surgeon in the U.S. army. At ![]() Turner’s Lane Military Hospital in Philadelphia, Mitchell treated battle veterans with severe nerve damage caused by bullet wounds. He observed that many of these men were rendered helpless and even “hysterical” by prolonged nerve pain (qtd. in Cervetti 77). Yet little could be done for these desperate patients, short of amputation of injured limbs and injection of narcotics for pain. So Mitchell adopted a regimen of rest and nutrition to help these men build up injured nerve tissue. As Nancy Cervetti observes, Mitchell’s treatment of injured soldiers involved the four major components that would later constitute the rest cure: “rest, a fattening diet, massage, and electricity” (74). The massage and electric stimulation of muscles were employed in lieu of physical exercise, since many patients were bedridden.

Turner’s Lane Military Hospital in Philadelphia, Mitchell treated battle veterans with severe nerve damage caused by bullet wounds. He observed that many of these men were rendered helpless and even “hysterical” by prolonged nerve pain (qtd. in Cervetti 77). Yet little could be done for these desperate patients, short of amputation of injured limbs and injection of narcotics for pain. So Mitchell adopted a regimen of rest and nutrition to help these men build up injured nerve tissue. As Nancy Cervetti observes, Mitchell’s treatment of injured soldiers involved the four major components that would later constitute the rest cure: “rest, a fattening diet, massage, and electricity” (74). The massage and electric stimulation of muscles were employed in lieu of physical exercise, since many patients were bedridden.

While the Civil War was an intellectually productive time for Mitchell, the experience of treating wounded veterans took its toll. Mitchell had a nervous breakdown in 1864. His self-diagnosed “neurasthenia with grave insomnia” was one of several brushes with nervous illness that Mitchell experienced during his lifetime (“The Treatment by Rest, Seclusion, etc.” 2035).

Approximately eight years later, Mitchell turned to the same therapies when faced with a different, but equally challenging set of patients: “the class well known to every physician,—nervous women, who as a rule are thin, and lack blood” (Fat and Blood 9). Mitchell explained that most of these patients had seen a range of different doctors without success, remaining “at the end as at the beginning, invalids, unable to attend to the duties of life” (Fat and Blood 10). The neurologist labeled some of these women hysterical; others he diagnosed with neurasthenia, a fashionable nervous disorder of the late 19th and early 20th centuries whose symptoms included insomnia, depression, fatigue, indigestion, anxiety, and headaches. Despite Mitchell’s own experience with neurasthenia, he could be quite unsympathetic to the complaints of these nervous women, particularly if they questioned his judgment or gave way to emotional outbursts.

The rest cure was highly regimented. Mitchell strove for an atmosphere of “order and control” that would serve as “moral medication” for coddled or selfish invalids (Fat and Blood 41). Typically, the patient was not allowed to read, write, sew, feed herself, or have contact with friends or family.[2] She had to lie down in bed for six weeks to two months. During this time, she needed the doctor’s permission to sit up in bed or turn over without assistance. Massage and electrical stimulation were used to ensure that her muscles did not atrophy from lying in bed day after day. But perhaps the most daunting aspect of the rest cure was the amount of food consumed. A typical daily menu was enormous, including “a light breakfast. . . a mutton chop as a midday dinner. . . bread and butter thrice a day,” and “three or four pints of milk, which are given at and after meals.” To this might be added iron supplements, doses of strychnine, arsenic, and cod liver oil, as well as “one pound of beef, in the form of raw soup. This is made by chopping up one pound of raw beef, placing it in a bottle with one pint of water and five drops of strong chlorohydric acid” (Fat and Blood 78-9). Women who refused this heavy diet might be force-fed through the nose or rectum, or, in rare cases, whipped to ensure obedience (Poirier 23).

Mitchell had a scientific rationale behind all of this food and inactivity. As he wrote in Fat and Blood, “a gain in fat up to a certain point seems to go hand in hand with a rise in all other essentials of health” (13). Noticing that many nervous women looked thin and anemic, Mitchell assumed that their physical and mental health would improve once they gained weight and red blood cells. The function of the rest cure was to help patients gain fat and blood as rapidly as possible, through a rich diet and minimal exertion. Mitchell typically weighed patients every day, and counted any substantial weight gain as a clinical success. He also saw a woman’s reproductive function as an index of her overall health. Mitchell’s successful case studies often ended when the patient got married, resumed menstruating, or carried a pregnancy to term. He saw these external indicators as virtually infallible evidence of a cure, regardless of what the patient might say about her mental state.

But the rest cure had a social as well as a scientific rationale. By removing a woman from her usual surroundings in the home, Mitchell hoped to break up “the whole daily drama of the sick-room, with its little selfishnesses and its craving for sympathy and indulgence” (Fat and Blood 37). This change was beneficial not just for the troublesome invalid herself, but also for the relatives whose strength and patience she might overtax. Mitchell wrote at length about the dangers of selfish patients exhausting devoted nurses, often creating more invalids in the process: “I have seen a hysterical, anemic girl kill in this way three generations of nurses. If you tell the patient she is basely selfish, she is probably amazed, and wonders at your cruelty” (32). The only way to cure such hysterical women, Mitchell explained, was to “substitute the firm kindness of a well-trained hired nurse” who would not humor the patient’s every whim (Fat and Blood 37, 32).

In his clinical writings, Mitchell was remarkably honest about the punitive function of his treatment for uncooperative female patients. Mitchell explained in Fat and Blood,

The rest I like for [female invalids] is not at all their notion of rest. To lie abed half the day, and sew a little and read a little, and be interesting and excite sympathy, is all very well, but when they are bidden to stay in bed a month, and neither to read, write, nor sew, and to have one nurse, – who is not a relative – then rest becomes for some women a rather bitter medicine, and they are glad enough to accept the order to rise and go about. (43)

As Cervetti notes, Mitchell seems to have conflated uncooperative female invalids with the malingerers he saw during the Civil War: that is, men who feigned illness in order to get out of combat duty (84). Mitchell and his colleagues at Turner’s Lane Military Hospital were adept at detecting and punishing malingerers, using etherization and electric stimulation of muscles to ascertain real versus feigned injuries. Once detected, malingerers could be punished by assigning them to unpleasant tasks around camp (see Keen et al.). Similarly, the rest cure could be used to discipline women whose illness became a means of avoiding household duties.

The rest cure was also, as Gilman’s experience suggests, an effective means of reinforcing traditional gender roles. By putting female patients to bed and forbidding them any sort of intellectual activity, Mitchell and his colleagues ensured that these women stayed in their proper sphere. Mitchell believed that intellectual achievement undermined a woman’s overall health, particularly her reproductive function. Thus, he discouraged female patients from seeking professional employment or engaging in prolonged study. “The woman’s desire to be on a level of competition with man and to assume his duties is, I am sure, making mischief,” he wrote in Doctor and Patient (13). “She is physiologically other than the man.” For a feminist like Gilman, such an attitude was bound to raise hackles.

Gilman was not the only female author to decry the oppressiveness of the rest cure. Mitchell’s treatment proved especially challenging for intellectual women who enjoyed reading, writing, and being active. Jane Addams, the founder ofIf the rest cure was unpleasant for some, it could be positively disastrous for women with undiagnosed physical ailments. Winifred Howells, the invalid daughter of author William Dean Howells, was sent to Mitchell in 1888 for the treatment of a disease supposed to be psychological in nature. Mitchell began force-feeding Winifred, whom he found to be obstinate and full of “hypochondriacal illusions” (Cervetti 88). Shortly thereafter, Winifred died. When Mitchell conducted an autopsy, he discovered that her complaint was organic in nature. Howells wrote of his daughter, “The torment that remains is that perhaps the poor child’s pain was all along as great as she fancied, if she was so diseased, as apparently she was” (qtd. in Cervetti 89). This episode suggests that on occasion, Mitchell’s refusal to listen to “nervous” female patients could have tragic results. Even if Winifred’s disease was incurable, as Mitchell alleged, the doctor’s failure to take her complaints seriously surely augmented her suffering in the weeks leading up to her death.

Yet for every failure, Mitchell could boast a number of success stories. Correspondence from patients suggests that the rest cure often worked, and that some women appreciated Mitchell’s stern bedside manner. Author Rebecca Harding Davis wrote a glowing recommendation of Mitchell to a friend after her own successful treatment: “I owe much to him – life – and what is better than life” (qtd. in Davis 97). Similarly, author Amelia Gere Mason, who saw Mitchell in 1882 for her neurasthenia, credited the doctor for “restoring ‘value’ to her life” (Schuster 705). She described his treatment as “autocratic,” yet effective, and found him to be a great listener (Schuster 706). Following Mason’s treatment, she and Mitchell maintained a strong friendship for 32 years, writing each other nearly 200 letters.

Other patients enjoyed the rest cure for reasons unrelated to their health. Mrs. Hattie Strong wrote home in 1883 about the string of celebrities coming in for treatment at Mitchell’s Philadelphia clinic. She enjoyed the people-watching and the attention of her famous physician, who earned her trust and admiration:

Dr. M[itchell] is about Papa’s age but looks much older. He has been a nervous invalid himself for many years and takes no rest except in summer when he goes to

Newport, and when he writes for recreation – last summer he wrote a novel. Not-yet-published. He also writes medical works and his opinion is authority. (Strong, Harriet Williams to Harriet Russell Strong, 10 February 1883)

This excerpt suggests that Mitchell used his own brushes with nervous illness to gain patients’ sympathy, and that his literary and medical celebrity helped him earn their trust. In Strong’s case, this strategy succeeded admirably. Despite being confined to her bed for 12 weeks and having ice packs applied to her spine twice a day, Strong was satisfied enough with her treatment to recommend Fat and Blood to her female relatives.

Such testimonials raise the question of why different women had such opposite reactions to Mitchell and his cure. Recently, David Schuster has challenged Mitchell’s popular reputation as a misogynist, pointing out that the doctor was also known for “respecting and enjoying the company of intelligent women” such as Mason, Sarah Butler Wister, and novelist Elizabeth Stuart Phelps (702). Mitchell actually encouraged these neurasthenic women to write as a form of therapy. Schuster concludes that the antagonism between Mitchell and Gilman stemmed from an initial misdiagnosis and a clash of personalities, rather than the doctor’s misogynistic attitude.

While it is important to acknowledge Mitchell’s positive interactions with women, he was generally more sympathetic toward the nervous men in his care.[3] While Mitchell put anxious women to bed, his male patients could choose either to rest or to journey West. Mitchell’s so-called “West Cure” for nervous men involved cattle roping, rough riding, hunting, and bonding with other men in rugged frontier locations. These activities supposedly rehabilitated neurasthenic men for further success in business and intellectual pursuits. Famous recipients of this cure included future U.S. President Theodore Roosevelt, painter Thomas Eakins, poet Walt Whitman, and novelist Owen Wister, the author of The Virginian (1902). West Cure patients typically enjoyed their treatment; Eakins, for instance, returned looking “built up miraculously” after his trip to the ![]() Dakota Badlands (qtd. in Stiles). Eakins lovingly recorded his journey in a series of letters, sketches, and paintings. (See Fig. 4.)

Dakota Badlands (qtd. in Stiles). Eakins lovingly recorded his journey in a series of letters, sketches, and paintings. (See Fig. 4.)

Even those men who opted for the rest cure were treated more leniently than female patients. For instance, Mitchell’s patient “Mr. P.D. was allowed to be out of bed once a day four hours, and to spend one at his place of business” (Fat and Blood 90).

Perhaps the most surprising adaptation of Mitchell’s rest cure, however, was its transfer onto British soil by William Playfair, M.D., a specialist in midwifery. In the late nineteenth century, medical theories and treatments normally traveled from Britain to America, not the reverse. An American treatment finding a place in British therapeutics was unusual in and of itself. It may also seem strange that a gynecologist like Playfair – rather than a neurologist or psychologist – should have adopted Mitchell’s regimen.[4] This can be explained by the popular association between women’s reproductive systems and their mental health during the nineteenth century. Hysteria, for example, was supposed by many to originate in the uterus (the term “hysteria” comes from the Greek word for “womb”). Playfair remarked that his interest in neurasthenia “was originally almost accidentally forced upon my attention from the very frequent association of this type of disease within the gynaecological work which is my special province” (qtd. in Sengoopta 101). Some women may have felt more comfortable telling their gynecologist about their nervous troubles than visiting a specialist, due to the stigma against mental illness (Sengoopta 101).

Physicians, too, were likely to assume that psychological symptoms had a gynecological origin. Like Mitchell, Playfair saw the rest cure as a relatively benign alternative to the ovariotomies and hysterectomies performed by other physicians in an effort to treat nervous disorders. Both physicians condemned such invasive surgeries when used as a means of treating mental illness (Sengoopta 101). To the extent that the rest cure prevented such drastic measures, it must have been a vast improvement in women’s health care.

British implementation of the rest cure sometimes deviated from Mitchell’s regimen, although the four basic elements – bed rest, overfeeding, massage, and electric stimulation of muscles – remained consistent. In Britain as in America, most patients were upper-middle-class women diagnosed with neurasthenia or hysteria, although some working-class hospital patients also received “brief periods of rest and care” (Marland 118). Of course, British doctors adapted the cure to suit their own needs and experience. For instance, Playfair prescribed drugs more frequently than Mitchell and advocated foreign travel during the later stages of recovery. He was also quicker to intervene in any minor gynecological problems, for instance, by correcting the position of the uterus or inserting a pessary (Marland 122).

The biggest challenge facing these British doctors was recreating Mitchell’s unique rapport with patients. As Mitchell himself acknowledged, the effectiveness of his cure depended to a large extent on the doctor’s personal magnetism and authoritarian bearing. Accordingly, British doctors tried to mimic his rigid control of the sickroom and the patient. For instance, Playfair insisted upon “firm kindness” and “showing that the practitioner has the superior will” (qtd. in Marland 121). Like Mitchell, Playfair removed patients from their homes and placed them in the care of trained nurses, so as to fully isolate them from friends and family during the recovery process. This isolation made it easier for the doctor to impose his will upon the patient. Even so, not every doctor could exert the same “electric. . . fascination” as Mitchell. As Mitchell’s biographer, Ernest Earnest, writes, “He had an influence over women not entirely accounted for by his medical skill” (84).

While first-hand accounts of patient experiences are rare, British fiction about the rest cure helps us to imagine what such an authoritarian doctor-patient relationship looked like in practice. Elizabeth Robins’ 1905 novel about neurasthenia, A Dark Lantern, provides an interesting case study of a woman who falls in love with her autocratic physician. Robins, a well-known actress and feminist, wrote the novel following her own rest cure in 1903.

The novel’s protagonist, London socialite Katherine Dereham, experiences the usual symptoms of nervous exhaustion following a failed relationship with an elusive German prince. She decides to try the rest cure under the care of Dr. Garth Vincent, a renowned physician who is rude and domineering toward his upper-crust patients (for instance, he forces one patient to eat her dinner after she has tried to hide it in the chimney). Although Katherine initially dislikes Vincent, she becomes so enamored of his forceful personality that she seduces and marries him. Once they are married, Vincent remains as controlling and disagreeable as ever, although the novel’s sentimental conclusion suggests a happier future for the couple.

The novel describes what must have been a common phenomenon. As Woolf put it, A Dark Lantern “explains how you fall in love with your doctor if you have a rest cure” (qtd. in Neve 153). In Freudian psychoanalysis, a patient’s attraction to the physician would be labeled as transference, and seen as a normal aspect of the therapeutic relationship. But this term and the phenomenon it describes were not widely known in England in 1905.[5] In any case, the tedium of the cure made it that much easier to develop erotic feelings for one’s doctor. During her own rest cure at the hands of Dr. Vaughn Harley, Robins became increasingly dependent on her doctor’s unpredictable visits. Without reading, writing, or letters from friends to occupy her time, Robins found herself “succumbing to the spell of his presence” (Gates 137).

An even more sinister account of the doctor-patient dynamic can be found in Woolf’s Mrs. Dalloway (1925), in which shell-shocked veteran Septimus Warren Smith consults a prominent advocate of the rest cure, Sir William Bradshaw. Faced with this hallucinating and suicidal patient, Bradshaw recommends “rest, rest, rest” and offers to treat Septimus at his “beautiful house in the country” (96-97). But Septimus, who dreads his upcoming rest cure, commits suicide by jumping off a balcony. Woolf’s narrator condemns Bradshaw as a hypocrite who upholds social convention in the name of medicine:

Worshipping proportion, Sir William not only prospered himself but made England prosper, secluded her lunatics, forbade childbirth, penalized despair, made it impossible for the unfit to propagate their views until they, too, shared his sense of proportion – his, if they were men, Lady Bradshaw’s, if they were women. (99)

Based on this description, Bradshaw resembles one of Woolf’s physicians, Sir George Savage, in whom “there seemed to be more of the man of the world. . . than of the mental specialist” (L. Woolf 82). Alternatively, Bradshaw may represent a composite of Woolf’s physicians rather than any one man in particular (Trombley 95).

Woolf clearly based this part of Mrs. Dalloway on her many experiences with the rest cure. She often underwent this treatment at the hands of fashionable Harley Street doctors, particularly during the years 1913-15, when she alternated between suicidal depression and “wild euphoria” (L. Woolf 161). Woolf hated the cure, feeling convinced that “eating and resting made her worse” (L. Woolf 155). Her husband, Leonard Woolf, grew to share her disillusionment. Virginia’s doctors, he wrote,

had not the slightest idea of the nature or the cause of Virginia’s mental state. . . all they could say was that she was suffering from neurasthenia and that, if she could be induced or compelled to rest and eat and if she could be prevented from committing suicide, she would recover (160).

The complete failure of the rest cure in this case may have been due to misdiagnosis, among other things. Leonard Woolf suspected that his wife suffered from manic depression rather than neurasthenia (161). For a person experiencing a manic phase, constant bed rest must have been torture. Some even speculate that Woolf committed suicide in 1941 due to her fear of undergoing the rest cure again, much like her character, Septimus (Orr 156).

In both England and America, the rest cure gradually declined in popularity during the first half of the twentieth century. By the 1940s, scientists such as Karl Menninger and Richard Asher decried aspects of the cure as unscientific and potentially harmful (Sharpe and Wessely 796). The rest cure was supplanted by talk therapy, particularly Freudian psychoanalysis. The diseases for which the rest cure was typically prescribed, neurasthenia and hysteria, also fell out of favor during these decades, to be replaced by more specific diagnoses such as depression, anxiety disorders, eating disorders, etc.

These changes reflected a broader shift in scientific culture. During the nineteenth century, scientists favored somatic explanations for mental illness; heredity, low energy levels, or even nerve lesions were blamed for most psychological dysfunction. These somatic explanations of mental illness seemingly called for a cure that focused on the body rather than the mind, and Mitchell’s rest cure fit the bill. By contrast, at the beginning of the twentieth century, psychoanalysts like Sigmund Freud and Carl Jung began to explore the psychic underpinnings of mental disorders. They viewed a patient’s past experiences as key to the development of mental pathology, and used talk therapy as a means of exploring and healing psychic wounds. The rest cure seemed to have no place in this new way of thinking.

Because the transition from somatic to psychological explanations of mental illness was gradual, so, too, was the disappearance of the rest cure. In fact, one might argue that it never entirely went away. Even today, women experiencing difficult pregnancies are put on bed rest. Moreover, we still view a woman’s body fat as an important index of her health and well-being, even though we associate heath with a leaner shape than Mitchell and his colleagues. Perhaps it is time to explore why these associations persist in modern culture, and how much we still owe to Mitchell’s way of thinking.

published October 2012

HOW TO CITE THIS BRANCH ENTRY (MLA format)

Stiles, Anne. “The Rest Cure, 1873-1925.” BRANCH: Britain, Representation and Nineteenth-Century History. Ed. Dino Franco Felluga. Extension of Romanticism and Victorianism on the Net. Web. [Here, add your last date of access to BRANCH].

WORKS CITED

Cervetti, Nancy. “S. Weir Mitchell Representing ‘a hell of pain’: From Civil War to Rest Cure.” Arizona Quarterly 59.3 (Autumn 2003): 69-96. Print.

Davis, Cynthia. Charlotte Perkins Gilman: A Biography. Stanford: Stanford UP, 2010. Print.

Earnest, Ernest. S. Weir Mitchell: Novelist and Physician. Philadelphia: U of Pennsylvania P, 1950. Print.

Gates, Joanne. Elizabeth Robins, 1862-1952. Actress, Novelist, Feminist. Tuscaloosa: U of Alabama P, 1994. Print.

Gilman, Charlotte Perkins. The Living of Charlotte Perkins Gilman: An Autobiography. Madison: U of Wisconsin P, 1990. Print.

–. “Why I Wrote the Yellow Wallpaper?” The Yellow Wall-paper, and the History of its Publication and Reception: A Critical Edition and Documentary Casebook. Ed. Julia Bates Dock. University Park: The Pennsylvania State UP, 1998. 86. Print.

–. “The Yellow Wall-paper.” The Yellow Wall-paper, and the History of its Publication and Reception: A Critical Edition and Documentary Casebook. Ed. Julia Bates Dock. University Park: The Pennsylvania State UP, 1998. 27-42. Print.

Keen, William Williams, Silas Weir Mitchell, and George Morehouse. “On Malingering, especially in regard to Simulation of Diseases of the Nervous System.” American Journal of Medical Science 48 (1864): 367-94. Print.

Marland, Hilary. “‘Uterine Mischief’: W.S. Playfair and his Neurasthenic Patients.” Cultures of Neurasthenia from Beard to the First World War. Ed. Marijke Gijswijt-Hofstra and Roy Porter. Amsterdam: Rodopi, 2001.117-39. Print.

Poirier, Suzanne. “The Weir Mitchell Rest Cure: Doctor and Patients.” Women’s Studies 10 (1983); 15-40. Print.

Micale, Mark. “Medical and Literary Discourses of Trauma in the Age of the American Civil War.” Neurology and Literature, 1860-1920. Ed. Anne Stiles. New York: Palgrave, 2007. 184-206. Print.

Mitchell, Silas Weir. Doctor and Patient. New York: The Classics of Medicine Library, 1994. Print.

–. Fat and Blood and How to Make Them. 2nd Edition. Philadelphia: J.B. Lippincott and Co, 1878. Print.

–. “The Treatment by Rest, Seclusion, etc. in Relation to Psychotherapy.” The Journal of the American Medical Association 50 (20 June 1908): 2033-2037. Print.

Neve, Michael. “Public Views of Neurasthenia: Britain, 1880-1930.” Cultures of Neurasthenia from Beard to the First World War. Ed. Marijke Gijswijt-Hofstra and Roy Porter. Amsterdam: Rodopi, 2001.141-59. Print.

Orr, Douglass. Virginia Woolf’s Illnesses. Ed. Wayne Chapman. Clemson, SC: Clemson U Digital P, 2004. Web.

Schuster, David. “Personalizing Illness and Modernity: S. Weir Mitchell, Literary Women, and Neurasthenia, 1870-1914.” Bulletin of the History of Medicine 79.4 (Winter 2005): 695-722. Print.

Sengoopta, Chandak. “‘A Mob of Incoherent Symptoms?’ Neurasthenia in British Medical Discourse, 1860-1920.” Cultures of Neurasthenia from Beard to the First World War. Ed. Marijke Gijswijt-Hofstra and Roy Porter. Amsterdam: Rodopi, 2001. 97-115. Print.

Sharpe, Michael and Simon Wessely. “Putting the Rest Cure to Rest—Again.” British Medical Journal 316 (14 March 1998): 796-800. Print.

Stiles, Anne. “Go Rest, Young Man.” Monitor on Psychology 43.1 (January 2012): 32. Print.

Strong, Harriet Williams (Russell) to Harriet Russell Strong. 10 February 1883. Cited with the permission of The Huntington Library, San Marino, CA.

Trombley, Stephen. All That Summer She was Mad: Virginia Woolf, Female Victim of Male Medicine. New York: Continuum, 1982. Print.

Woolf, Leonard. Beginning Again: An Autobiography of the Years 1911 to 1918. New York: Harcourt, Brace, and World, Inc, 1964. Print.

Woolf, Virginia. Mrs. Dalloway. New York: Harcourt, Inc., 1981. Print.

ENDNOTES

[1] On the unreliability of Gilman’s autobiography, particularly as regards her rest cure experiences, see Davis 95-105. Davis suggests that Gilman actually found her stay at Mitchell’s sanitarium relatively pleasant, and that her symptoms worsened when she returned home to her unhappy domestic situation.

[2] The rest cure could be modified to suit the needs of individual patients. The case studies in Fat and Blood, for instance, demonstrate that Mitchell allotted different amounts of food and bed rest to each patient, depending on his or her symptoms. He also lifted prohibitions on working and socializing in certain circumstances, especially for male patients.

[3] Exceptions to this rule include the alleged malingerers Mitchell saw during the Civil War, to whom he could be remarkably cruel. He was also unsympathetic towards the few men he deemed “hysterical,” usually those who proved violent, unmanageable, or effeminate. See Micale for a discussion of such cases.

[4] In this context, it is important to note that medical specializations were not nearly as firmly established in the late nineteenth century as they are today. On the changing status of neurology, psychiatry, and gynecology in late Victorian Britain, see Sengoopta.

[5] Leonard Woolf wrote that in even as late as 1914, few Britons “recognized and understood the greatness of Freud” (167).