Abstract

Mary Wollstonecraft’s Vindication of the Rights of Woman (1792) laid out the tenets of what today we call ‘equality’ or ‘liberal’ feminist theory. She further promoted a new model of the nation grounded on a family politics produced by egalitarian marriages.

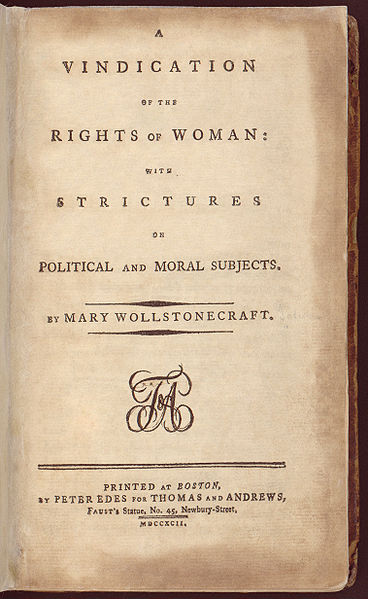

[1]Invoking the radical French and British political discourse surrounding the early days of the French Revolution, in 1792, in A Vindication of the Rights of Woman, Wollstonecraft threw down the gauntlet, not only to her male readers, but equally important, to the women of her day, as she called for a “REVOLUTION in female manners” (230). A Vindication of the Rights of Woman proposed a model of what we would now call “equality” or “liberal” feminism. Grounded on the affirmation of universal human rights endorsed by such Enlightenment thinkers as Voltaire, Jean-Jacques Rousseau, and John Locke—the affirmation that underpinned both the American Revolution in 1776 and the French Revolution in 1789—Wollstonecraft argued that females are in all the most important aspects the same as males, possessing the same souls, the same mental capacities, and thus the same human rights. True, the first edition of the Vindication (January 1792) attributed a physical superiority to the male, acknowledging his ability to overpower the female of the species with his greater brute strength:

. . . the female, in general is inferior to the male. The male pursues, the female yields—this is the law of nature; and it does not appear to be suspended or abrogated in favour of woman. This physical superiority cannot be denied—and it is a noble prerogative! (24, n4).

However, only six months later, by the end of the second edition of 1792, Wollstonecraft effectively denied the significance and even the necessary existence of male physical superiority. She first reduces the physical difference between males and females, rewriting the above passage thus:

In the government of the physical world it is observable that the female in point of strength is, in general, inferior to the male. This is the law of nature, and does not appear to be suspended or abrogated in favour of women. A degree of physical superiority cannot, therefore, be denied—and it is a noble prerogative! (24, my italics).

She then insists that women’s virtues—“strength of mind, perseverance and fortitude”—are the “same in kind” if not yet in “degree” (55). She next adamantly denies “the existence of sexual virtues, not excepting modesty” (71), in effect erasing any essentialist difference between males and females. She concludes by suggesting that if females were allowed the same exercise as males, then they would arrive at a “perfection of body” that might well erase any “natural superiority” of the male body (111).

On this philosophical assumption of sexual equality and even potential sameness, Wollstonecraft mounted her campaign for the reform of female education, arguing that girls should be educated in the same subjects and by the same methods as boys. She further advocated a radical revision of British law to enable a new, egalitarian marriage in which women would share equally in the management and possession of all household resources. We must remember that British women in 1790 lived under the legal condition of couverture (being “covered” by the body of another), which meant they could not own or distribute their own property or possess custody of their own children. Legal reformer Barbara Leigh-Smith Bodichon summarized the laws, still in effect in 1854, thus:

A man and wife are one person in law; the wife loses all her rights as a single woman, and her existence is entirely absorbed in that of her husband. He is civilly responsible for her acts; she lives under his protection or cover, and her condition is called couverture.

A woman’s body belongs to her husband; she is in his custody, and he can enforce his sexual right by a writ of habeas corpus.

What was her personal property before marriage, such as money in hand, money at the bank, jewels, household goods, clothes, etc., becomes absolutely her husband’s, and he may assign or dispose of them at his pleasure whether he and his wife live together or not. . . .

The legal custody of children belongs to the father. During the lifetime of a sane father, the mother has no rights over her children, except a limited power over infants, and the father may take them from her and dispose of them as he thinks fit. (6)

To Wollstonecraft, couverture was tantamount to slavery. Women, she argued, possessed the same souls and natural rights as men and should hold the same civil and legal rights.

She demanded that women be paid—and paid equally—for their labor, that they gain the civil and legal right to possess and distribute property, that they be admitted to all the most prestigious professions. And she argued that women (together with all disenfranchised men) should be given the vote: “I really think that women ought to have representatives, instead of being arbitrarily governed without any direct share allowed them in the deliberations of government” (179).[2]

To defend her utopian vision, Wollstonecraft described in detail the errors and evils of her society’s contemporary definition of the female as the subordinate helpmate of the male. Referring to the widely supported views of John Milton and Rousseau, she sardonically attacked their portrayals of women. When Milton tells us, she wrote with heavy sarcasm,

That women are formed for softness and sweet attractive grace [Paradise Lost, 4:297-299], I cannot comprehend his meaning, unless, in the true Mahometan strain he meant to deprive us of souls, and insinuate that we were beings only designed to gratify the senses of man when he can no longer soar on the wing of contemplation (36).

She saved her bitterest attacks for Rousseau, whose gender policies contradicted his radical politics of individual choice and the social contract. She was particularly critical of the portrait of the ideal woman Rousseau drew in his novel Emile. Portraying Sophie (“female wisdom”) as submissive, loving, and ever faithful, Rousseau there asserted:

The first and most important qualification in a woman is good nature or sweetness of temper: formed to obey a being so imperfect as man, often full of vices, and always full of faults, she ought to learn betimes even to suffer injustice, and to bear the insults of a husband without complaint (Vindication 108).

Much of A Vindication is devoted to illustrating the damage wrought by this definition of women’s nature and social role. Upper- and middle-class girls in Wollstonecraft’s day were taught to become adept at arousing and sustaining (but never fully satisfying) male sexual desire in order to capture husbands upon whom their financial welfare depended. (It was not considered “respectable” for a woman to work for money.) They were thus obsessed with personal appearance, with beauty and fashion. Encouraged to be “delicate” and refined, many were what we would now recognize as anorexic or bulimic.[3] Worse, this model of “good” femininity encouraged, in Wollstonecraft’s view, hypocrisy and insincerity. Trained to be flirts and sexual teases, women were taught to arouse male sexual desire by allowing their suitors to take “innocent freedoms” or “liberties” with their person but were forbidden to experience or manifest sexual desire themselves. Since they received no rational or useful education but were trained only in the “female accomplishments” (penmanship, fine sewing, dancing, a smattering of foreign languages, singing, sketching), women were kept, Wollstonecraft insisted, “in a state of perpetual childhood” (25). They were thus “slaves” to their fathers and husbands, but, in revenge, cruel and petty tyrants to their daughters and servants (even as they continued to use their sexual “wiles” to manipulate their husbands whenever possible).

The revolution in female manners demanded by Wollstonecraft would, she insisted, dramatically change both genders. It would produce women who were sincerely modest, chaste, virtuous, and Christian, women who acted with reason and prudence and generosity. It would produce men who—rather than being trained to become petty household tyrants or slave-masters over their female dependents or “house-slaves” (122)—would treat women with respect and act towards all with benevolence, justice and sound reason. It would eliminate the “want of chastity in men,” a depravity of appetite that in Wollstonecraft’s view was responsible for the social production of unmanly “equivocal beings” (170). And it would produce egalitarian marriages based on compatibility, mutual affection and respect. These are, above all, marriages of rational love, rather than erotic passion. Insisting that sexual passion does not last, she argued that “the one grand truth women have yet to learn, though most it imports them to act accordingly” is “that in the choice of a husband, they should not be led astray by the qualities of a lover—for a lover the husband, even supposing him to be wise and virtuous, cannot long remain” (148). Although Wollstonecraft has been condemned by twentieth-century feminists as being hostile to female sexual desire, she did not mean that women should foreswear sexual passion altogether. Rather, as her own life suggests, she embraced sexual desire. She felt strongly, however, that women should channel their sexual passion toward a person whom they rationally deemed to be a suitable life-partner, one with shared interests and values. “Women as well as men ought to have the common appetites and passions of their nature,” she insisted, emphasizing that “they are only brutal when unchecked by reason” (161). As she concluded,

we shall not see women affectionate till more equality be established in society, till ranks are confounded and women freed, neither shall we see that dignified domestic happiness, the simple grandeur of which cannot be relished by ignorant or vitiated minds; nor will the important task of education ever be properly begun till the person of a woman is no longer preferred to her mind. (228)

Wollstonecraft is here advocating what we might call a “family politics,” the argument that the relationship between the sexes in the home becomes the model for all political relationships between rulers and ruled, as well as the pattern for the relationships between nation-states. As she was the first to articulate, the personal is the political. By conceiving the egalitarian family as the prototype of a genuine democracy, a family in which husband and wife not only regard each other as equals in intelligence, sensitivity, and power but also participate equally in childcare and decision-making, Wollstonecraft in A Vindication of the Rights of Woman introduced a truly revolutionary society. Wollstonecraft shared the French Enlightenment philosophes’ affirmation of reason and wit, of sound moral principles, and of good taste grounded on wide learning. But she contested the traditional affirmation of the father as the ultimate social, political, and religious authority—as he was even in the new French Republic. Where Enlightenment thinkers and nonconformist writers such as Voltaire, Thomas Paine, and Thomas Jefferson challenged the authority of the father in the name of the younger son, or challenged the authority of the King in the name of the self-made common man, Wollstonecraft categorically challenged the rights of males in the name of all females. At her most radical, she even suggested that rational women might possess a greater capacity than men for virtue and the performance of moral duty, and thus for political leadership.

HOW TO CITE THIS BRANCH ENTRY (MLA format)

published October 2011

Mellor, Anne. “On the Publication of Mary Wollstonecraft’s A Vindication of the Rights of Woman.” BRANCH: Britain, Representation and Nineteenth-Century History. Ed. Dino Franco Felluga. Extension of Romanticism and Victorianism on the Net. Web. [Here, add your last date of access to BRANCH].

WORKS CITED

Badowska, Ewa. “The Anorexic Body of Liberal Feminism: Mary Wollstonecraft’s A Vindication of the Rights of Woman.” Tulsa Studies in Women’s Literature 17:2 (1998): 283-303. Print

Bodichon, Barbara Leigh-Smith. A Brief Summary in Plain Language of the Most Important Laws Concerning Women: Together with a Few Observations Thereon. London, 1854. Print.

Mellor, Anne K. Romanticism and Gender. London: Routledge, 1993. Print.

Silver, Anna Krugovoy. Victorian Literature and the Anorexic Body. Cambridge: Cambridge UP, 2002. Print.

Taylor, Barbara. Mary Wollstonecraft and the Feminist Imagination. Cambridge: Cambridge UP, 2003. Print.

Wollstonecraft, Mary. A Vindication of The Rights of Woman and The Wrongs of Woman, or Maria. Eds. Anne K. Mellor and Noelle Chao. New York: Pearson Education – Longman Cultural Editions, 2007. Print.

RELATED BRANCH ARTICLES

ENDNOTES

[1] Sections of this essay first appeared in the introduction to A Vindication of The Rights of Woman and The Wrongs of Woman, or Maria, edited by Anne K. Mellor and Noelle Chao.

[2] Mary Wollstonecraft here echoes the battle-cry of the American colonists in the War with the Colonies or what Americans call the American Revolution (1776)—“No taxation without representation!”, in other words, we will not pay taxes unless we have the vote and can elect our own members of Parliament (see Mellor, 31-9). Barbara Taylor hears Wollstonecraft’s challenge within the context of British parliamentary politics, and believes that Wollstonecraft is asking that a specific member of Parliament “represent” the interests of women, even though women would not have the vote or suffrage to determine the choice of this (male) representative (Taylor, 215-6).

[3] On this issue, see Ewa Badowska and Anna Krugovoy Silver.