Abstract

Although the rise of modern British spy fiction is usually dated to the Edwardian period, with the names of Kipling, Conrad and Buchan among the first to be mentioned, the genre owes its existence to a little-noted precursor in late Victorian popular literature: the Russian Nihilist romance. Many of the ideological and formal aspects of the genre can be traced back to the tales of police espionage, terrorist revolutionaries, and double agents that titillated audiences in the last decades of the nineteenth century. In the 1880s and 90s, the age-old literary figure of the spy underwent a number of transformations that would establish its new meanings for the new century.

Spy fiction has invariably proved to be an accurate barometer of political anxieties, at times even a potent fomenter of public paranoia in its own right, and it owes this uncanny ability to its origins in the political pulp fiction of the late nineteenth century. Although the spy novel attained its recognizably modern form in the 1900s with Erskine Childers’s The Riddle of the Sands (1903) and William Le Queux’s and Edward Phillips Oppenheim’s numerous pot-boilers, Victorian detective fiction, imperial adventure, and invasion scare or future war fantasy had already prepared much of the ground for it.[1] But this article will focus on a lesser known progenitor genre popular in the 1880s and 90s, which contributed in its own way to spy fiction’s not-so-immaculate conception: the Russian Nihilist romance.

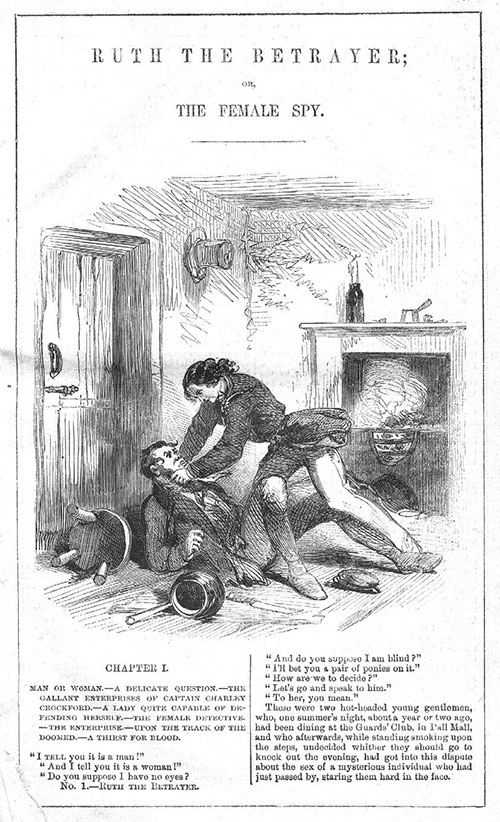

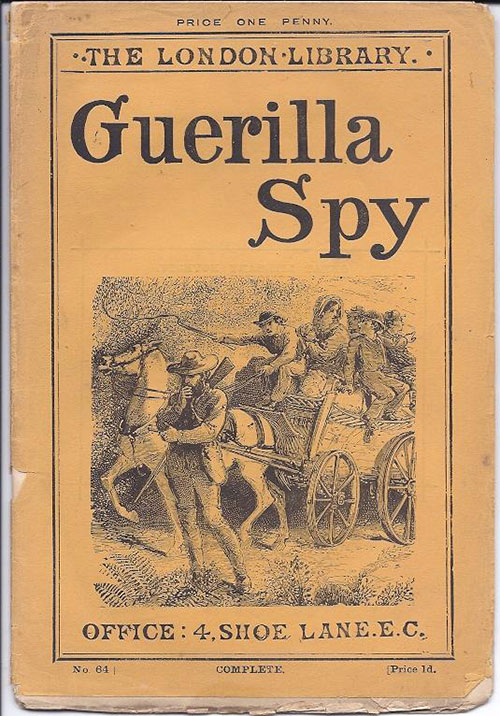

Spies have, of course, figured in literature since ancient times: hardly surprising considering spying’s reputation as the second oldest profession. In Britain, writers had worked as spies (or had been taken for spies) long before Graham Greene: one need only recall Christopher Marlowe in the sixteenth century, or William Wordsworth and Samuel Taylor Coleridge two hundred years later. In the nineteenth century, after the spy scares of the Napoleonic Wars, espionage was never far from readers’ minds. Spies made appearances in political squibs upon royalty, such as the 1820 verse satire of the trial of Queen Caroline, A Spy upon Spies; or, The Milan Chambermaid; Developing Certain Particulars of the Mysterious Contents of the Green Bag; and they showed up among the heroes of the penny dreadfuls, alongside the usual pirates and highway robbers. In 1862-3, Ruth the Betrayer; or, The Female Spy (Fig. 1) went through 52 penny numbers, and in the same years “The London Library” reprinted Guerilla Spy (Fig. 2), an American Civil War story.[2] In America, a vibrant undergrowth of spy stories had sprung up in the cheap story-papers in the 1840s and in dime novels a few decades later,[3] and it was common practice for British publishers to pirate this material for home consumption. But the spy motif was not limited to the lowest, disreputable reaches of the market. In 1870, The Million, “a family journal of literature, science, and art, for the home circle,” published a serial by the famous penny dreadful author Bracebridge Hemyng, called The Spies of London; or, The Companions of the Temple.[4]

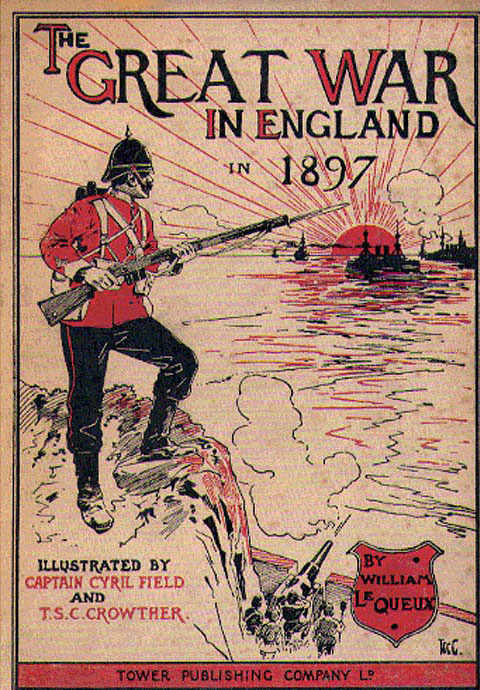

As can be seen from the titles alone, these spies were not the kind readers immediately think of today—pieces in the great chess game of international diplomacy, guardians or subverters of national security, agents of intelligence bureaucracies and state secret services. But in the 1880s and especially the 1890s, as European imperial rivalries and arms races heated up, various approximations to the type began to crop up here and there, and most obviously, in the imaginary invasion narratives that had proliferated since the 1871 publication of George Chesney’s The Battle of Dorking.[5] In The Great War in England in 1897 (1894), published in book form three years before the title date (Fig. 3), William Le Queux introduced a figure that would become the prototype of the foreign spy for the next several decades—a British-based German Jew “in the secret pay of the tsar” who steals “secret treaty plans” and precipitates an invasion byBut spy fiction had another late Victorian parent, and it too spoke with an unmistakable Russian accent. Three dates are of particular relevance in this neglected history. In 1878, the revolutionary Vera Zasulich shot at and wounded the Governor of ![]() St. Petersburg, initiating a wave of political violence. The following year, the terrorist organization People’s Will, which was dedicated to the assassination of key government figures, was formed. In 1881, it successfully carried out its primary goal of killing Tsar Alexander II. Russian secret police activity went into overdrive as police spies infiltrated revolutionary groups, and leading figures were arrested and executed. The political developments in Russia were widely covered by the British press and provided an inexhaustible source of sensational material for interested British writers. By the early 1880s, love and adventure among the Russian Nihilists emerged as one of the most popular strands of “terrorist” fiction.[6] It came with an array of indispensable accoutrements including bombs, floggings, terrible oaths, secret societies, Siberian exile, benevolent or malevolent Tsars, and beautiful female revolutionaries stabbing their tormentors or committing suicide instead of assassinating their loved ones. There are echoes of this as late as the 1934 revolutionary espionage film British Agent, based on the Russian memoir of Robert Bruce Lockhart, the British diplomat and secret agent who was himself an avid reader of late Victorian authors of Russian-set adventure bestsellers such as H. S. Merriman.

St. Petersburg, initiating a wave of political violence. The following year, the terrorist organization People’s Will, which was dedicated to the assassination of key government figures, was formed. In 1881, it successfully carried out its primary goal of killing Tsar Alexander II. Russian secret police activity went into overdrive as police spies infiltrated revolutionary groups, and leading figures were arrested and executed. The political developments in Russia were widely covered by the British press and provided an inexhaustible source of sensational material for interested British writers. By the early 1880s, love and adventure among the Russian Nihilists emerged as one of the most popular strands of “terrorist” fiction.[6] It came with an array of indispensable accoutrements including bombs, floggings, terrible oaths, secret societies, Siberian exile, benevolent or malevolent Tsars, and beautiful female revolutionaries stabbing their tormentors or committing suicide instead of assassinating their loved ones. There are echoes of this as late as the 1934 revolutionary espionage film British Agent, based on the Russian memoir of Robert Bruce Lockhart, the British diplomat and secret agent who was himself an avid reader of late Victorian authors of Russian-set adventure bestsellers such as H. S. Merriman.

The Russian Nihilist motif was instrumental in developing the institutional dimension of literary portrayals of spying, for the revolutionary Nihilist almost never appeared without his nemesis, the spy of the Tsarist secret police. A favourite twist on this scenario —the double agent—was still being exploited by Joseph Conrad in the Edwardian period. In actual fact, foreign secret police spies had roamed the streets of Britain for much of the nineteenth century—we know what the interior of Karl Marx’s ![]() Soho flat looked like thanks to their reports. European political police spies and agents provocateurs, especially French ones, also populated the “yellowback police novels” of the 1850s and 60s (Dever 228). The literary connection between spying and revolution was cemented in this French context at mid-century. But with the mounting vogue for Russian Nihilists in the 1880s and 90s, many of the tropes that would feed through into twentieth-century spy fiction—the infiltration of the enemy camp, the puncturing of the disguises behind which the foreign assassin or terrorist conceals himself, the danger posed by the sexualised femme fatale and her secret agents, the conspiracy unmasked, secret signs, political intrigue behind the scenes upon which questions of war and peace and the fate of empires hang—were updated in line with a new international political context. All those fin-de-siècle plots revolving around the struggle between the undercover police spy—the upholder of the state—and the agent of the shadowy international secret society intent on blowing up the status quo with dynamite and “infernal machines” look forward, unmistakably, to James Bond.

Soho flat looked like thanks to their reports. European political police spies and agents provocateurs, especially French ones, also populated the “yellowback police novels” of the 1850s and 60s (Dever 228). The literary connection between spying and revolution was cemented in this French context at mid-century. But with the mounting vogue for Russian Nihilists in the 1880s and 90s, many of the tropes that would feed through into twentieth-century spy fiction—the infiltration of the enemy camp, the puncturing of the disguises behind which the foreign assassin or terrorist conceals himself, the danger posed by the sexualised femme fatale and her secret agents, the conspiracy unmasked, secret signs, political intrigue behind the scenes upon which questions of war and peace and the fate of empires hang—were updated in line with a new international political context. All those fin-de-siècle plots revolving around the struggle between the undercover police spy—the upholder of the state—and the agent of the shadowy international secret society intent on blowing up the status quo with dynamite and “infernal machines” look forward, unmistakably, to James Bond.

In 1887, the famous actor-manager Herbert Beerbohm Tree’s portrayal of the Head of the Russian secret police in the play The Red Lamp proved a big hit on the London stage. The play featured a princess, the princess’s brother—a double agent working for the secret police and posing as chief of the Nihilist revolutionaries—and a “cache of dynamite” upon whose discovery the plot hinged (Senelick 29). In the same year, Oscar Wilde published Lord Arthur Savile’s Crime, a comic story set in London, in which the title character visits a Russian “Nihilist agent” living in ![]() Bloomsbury to get the address of a bomb-maker. It was not just Russian police spies who had their work cut out for them, in other words; British ones also had to get in on the act. “

Bloomsbury to get the address of a bomb-maker. It was not just Russian police spies who had their work cut out for them, in other words; British ones also had to get in on the act. “![]() Scotland Yard would give a good deal to know this address, my dear fellow,” says Wilde’s Nihilist agent. “‘They shan’t have it,’ cried Lord Arthur, laughing…” (42).[7] Even though diplomatic intelligence gathering was in its infancy in the 1880s, the surveillance of radical groups and individuals who were perceived to pose a threat to domestic security was much more developed, and it involved international governmental collaboration because the radicals in question themselves showed no respect for borders.[8] By this time, the British police had perfected the use of informers and agents provocateurs in targeting the foreign anarchists, Fenians and other revolutionaries found on British soil to an extent exceeding anything seen in the 1850s or 60s, when police informants and private detectives, especially fictional ones, were resolutely domestic in their focus.

Scotland Yard would give a good deal to know this address, my dear fellow,” says Wilde’s Nihilist agent. “‘They shan’t have it,’ cried Lord Arthur, laughing…” (42).[7] Even though diplomatic intelligence gathering was in its infancy in the 1880s, the surveillance of radical groups and individuals who were perceived to pose a threat to domestic security was much more developed, and it involved international governmental collaboration because the radicals in question themselves showed no respect for borders.[8] By this time, the British police had perfected the use of informers and agents provocateurs in targeting the foreign anarchists, Fenians and other revolutionaries found on British soil to an extent exceeding anything seen in the 1850s or 60s, when police informants and private detectives, especially fictional ones, were resolutely domestic in their focus.

Members of the public, the press, and the official classes could not always tell the difference between the various groups attempting to undermine the establishment, but they were much more clear about the secretive methods used by law enforcement, such as the newly formed Special Branch, to combat them. During the mid-century zenith of Liberalism, though literary secret agents were all the rage, public approval for police espionage activities had been non-existent; ungentlemanly letter-opening by the government was liable to provoke a scandal.[9] (See Marjorie Stone, “Joseph Mazzini, English Writers, and the Post Office Espionage Scandal: Politics, Privacy, and Twenty-First Century Parallels″ and Kate Lawson, “Personal Privacy, Letter Mail, and the Post Office Espionage Scandal, 1844.″) But as the mood changed and xenophobic militarism reached new heights at the turn of the twentieth century, spying of all sorts became more and more acceptable. As the Quarterly Review declared in 1893, “the faithful political spy, like the faithful detective, deserves well of the State which employs him” (qtd. in Stafford 507). Such sentiments were unthinkable in the 1850s, but by the 1900s, the fictional gentleman spy—that patriotic upright Englishman and pillar of society—could engage in espionage with moral impunity. Oppenheim and Le Queux, obsessed with conspiratorial cosmopolitan networks, merely applied the model of “clandestine police operations” against subversives “to the context of diplomacy and international relations” (Stafford 505, 507).

But one should remember that in Nihilist texts the English protagonist, if present at all (something one could by no means take for granted), rarely fulfilled the role of the faithful servant of the state around which the spy genre would shortly coalesce. Far from being a police spy himself, he was, in fact, sometimes sympathetic to the Nihilist cause, even to the extent of joining a terrorist organisation. Griffith Jones’s The Angel of the Revolution (1893) is the prime example (Fig. 4). More typical still were protagonists who committed to carrying out an assassination on behalf of a secret society and then had a change of heart: their mental deliberations and emotional turmoil were given respectful attention. Secret political organisations were, after all, qualitatively different from the enemy states bent on invasion found in future war scenarios. It was possible to empathise with the point of view of an aggrieved hero or heroine who joined them, whereas only a contemptible traitor would sell British secrets to the Kaiser. Analogously, agents of a friendly foreign government who took part in international secret police collaboration to hound dangerous revolutionaries appeared in a different light from the agents of hostile governments who undermined national security.

Such distinctions threw up all sorts of narrative complexities and unexpected twists. In Oppenheim’s Mysterious Mr. Sabin of 1898, for instance, the machinations of a French-German spy who steals “a detailed survey of Britain’s coastal defences” are foiled by an international secret society that has a soft spot for Britain precisely because it “grants asylum to Nihilists” (Trotter, “Politics of Adventure” 43). Nihilists could be heroes as well as villains. If geopolitical rivalry and German spy mania in the Edwardian period consolidated the classic form of the spy novel, its Nihilist precursor in the late nineteenth century operated in a different political framework. International terrorists were a threat, but in the Russian context they could also be seen as freedom fighters and their equivocal nature accounted for many of the sympathetic notes in the Nihilist fiction of the 1880s and 90s. When the real-life Russian Nihilist assassin and British resident celebrity, Sergey Stepniak, published his own terrorist novel, The Career of a Nihilist, in 1889, it was warmly received in the British press. One cannot imagine a real German spy twenty years later publishing—to popular acclaim—an account of how he outwitted the British secret service.

It is worth concluding on this point. Spy fiction, in the form that it took in the first decades of the twentieth century, was a genre with very clearly set ideological parameters. Though it drew on the suspicion of dirty foreigners infiltrating the British body politic that also defined the anti-revolutionary paranoia of the preceding decades, it could not share the Nihilist novel’s occasional willingness to step into the shoes of the enemy. The foreign spy of Edwardian fiction was, in moral terms, the direct descendant of those Russian soldiers in ![]() Birmingham who “murdered [babes] before the eyes of their parents” by impaling them on their “gleaming Russian bayonets” in Le Queux’s The Great War in England (66). He was, in other words, beyond the pale: his invasive machinations just as damaging as the bayonets of the invading enemy soldier. But the spy novel evolved over the course of the twentieth century, attaining an ever-greater degree of psychological and political subtlety, and transcending its roots in invasion fantasy. The moral shades of grey so typical of spy fiction’s neglected Nihilist progenitor assume new relevance in light of this more recent generic history.

Birmingham who “murdered [babes] before the eyes of their parents” by impaling them on their “gleaming Russian bayonets” in Le Queux’s The Great War in England (66). He was, in other words, beyond the pale: his invasive machinations just as damaging as the bayonets of the invading enemy soldier. But the spy novel evolved over the course of the twentieth century, attaining an ever-greater degree of psychological and political subtlety, and transcending its roots in invasion fantasy. The moral shades of grey so typical of spy fiction’s neglected Nihilist progenitor assume new relevance in light of this more recent generic history.

published December 2016

HOW TO CITE THIS BRANCH ENTRY (MLA format)

Vaninskaya, Anna. “Russian Nihilists and the Prehistory of Spy Fiction.” BRANCH: Britain, Representation and Nineteenth-Century History. Ed. Dino Franco Felluga. Extension of Romanticism and Victorianism on the Net. Web. [Here, add your last date of access to BRANCH].

WORKS CITED

Bold, Christine. “Secret Negotiations: The Spy Figure in Nineteenth-century American Popular Fiction.” Wark: 17-29. Print.

British Agent. Directed by Michael Curtiz. Warner Bros., 1934.

Butterworth, Alex. The World That Never Was: A True Story of Dreamers, Schemers, Anarchists and Secret Agents. London: The Bodley Head, 2010. Print.

Clarke, I. F. Voices Prophesying War, Future Wars 1763—3749. Oxford: Oxford UP, 1992. Print.

Chesney, George. The Battle of Dorking. Edinburgh: Blackwood, 1871. Print.

Childers, Erskine. The Riddle of the Sands. A Record of Secret Service Recently Achieved. London: Smith, Elder & Co., 1903. Print.

Denning, Michael. Cover Stories: Narrative and Ideology in the British Spy Thriller. London: Routledge & Kegan Paul, 1987. Print.

Dever, Carolyn. “‘An Occult and Immoral Tyranny’: The Novel, the Police, and the Agent Provocateur”. The Literary Channel: The Inter-National Invention of the Novel. Eds. Margaret Cohen and Carolyn Dever. Princeton: Princeton UP, 2002: 225-250. Print.

Ellis, Edward. Ruth the Betrayer: or, the Female Spy. London: John Dicks, 1863. Print.

Frank, Michael C. “Plots on London: Terrorism in Turn-of-the-Century British Fiction.” Frank and Gruber: 41-65. Print.

— and Eva Gruber, eds. Literature and Terrorism: Comparative Perspectives. Amsterdam: Rodopi, 2012. Print.

Glazzard, Andrew. Conrad’s Popular Fictions: Secret Histories and Sensational Novels. Basingstoke: Palgrave, 2016. Print.

Griffith Jones, George Chetwynd. The Angel of the Revolution: A Tale of the Coming Terror. London: Tower Publishing Co., 1893. Print.

Hepburn, Alan. Intrigue: Espionage and Culture. New Haven: Yale UP, 2005. Print.

Hughes, Michael and Harry Wood. “Crimson Nightmares: Tales of Invasion and Fears of Revolution in Early Twentieth-Century Britain.” Contemporary British History 28.3 (2014): 294-317. DOI: 10.1080/13619462.2014.941817

Le Queux, William. The Great War in England in 1897. London: Tower Publishing Co., 1894. Print.

Melchiori, Barbara. Terrorism in the Late Victorian Novel. London: Croom Helm, 1985. Print.

O Donghaile, Deaglan. Blasted Literature: Victorian Political Fiction and the Shock of Modernism. Edinburgh: Edinburgh UP, 2011. Print.

One of the Principal Spies. A Spy upon Spies; or, The Milan Chambermaid; Developing Certain Particulars of the Mysterious Contents of the Green Bag. London: John Fairburn, [1820?]. Print.

Oppenheim, E. Phillips. Mysterious Mr. Sabin. London: Ward, Lock & Co., 1898. Print.

Porter, Bernard. The Refugee Question in Mid-Victorian Politics. Cambridge: Cambridge UP, 1979. Print.

Senelick, Laurence. “‘For God, For Czar, for Fatherland’: Russians on the British Stage from Napoleon to the Great War.” Russia in Britain, 1880-1940: From Melodrama to Modernism. Eds. Rebecca Beasley and Philip Ross Bullock. Oxford: Oxford UP, 2013: 19-34. Print.

Snyder, Robert Lance. The Art of Indirection in British Espionage Fiction: A Critical Study of Six Novelists. Jefferson, NC: McFarland, 2011. Print.

Stafford, David A. T. “Spies and Gentlemen: The Birth of the British Spy Novel, 1893-1914.” Victorian Studies 24.4 (Summer 1981): 489-509. JSTOR. Web. 8 Apr. 2014.

Stepniak, Sergey. The Career of a Nihilist. London: Walter Scott. 1889. Print.

Tracy, Louis. The Final War. London: C. A. Pearson, 1896. Print.

Trotter, David. The English Novel in History, 1895-1920. London: Routledge, 1993. Print.

—. “The Politics of Adventure in the Early British Spy Novel.” Wark: 30-54. Print.

Vaninskaya, Anna. “‘Truth About Russia’: Russia in Britain at the Fin de Siècle.” The Edinburgh Companion to Fin de Siècle Literature, Culture and the Arts. Ed. Josephine Guy. Edinburgh: Edinburgh UP. Forthcoming 2017. Print.

Wade, Stephen. Spies in the Empire: Victorian Military Intelligence. London: Anthem Press, 2007. Print.

Wark, Wesley K., ed. Spy Fiction, Spy Films and Real Intelligence. New York: Routledge, 1991. Print.

Wilde, Oscar. Lord Arthur Savile’s Crime, Complete Shorter Fiction. Ed. Isobel Murray. Oxford: Oxford UP, 1998. Print.

—. The Major Works. Ed. Isobel Murray. Oxford: Oxford UP, 2000. Print.

Wisnicki, Adrian S. Conspiracy, Revolution, and Terrorism from Victorian Fiction to the Modern Novel. New York: Routledge, 2008. Print.

Woods, Brett F. Neutral Ground: A Political History of Espionage Fiction. New York: Algora Publishing, 2008. Print.

RELATED BRANCH ARTICLES

Kate Lawson, “Personal Privacy, Letter Mail, and the Post Office Espionage Scandal, 1844″

ENDNOTES

[1] On this pedigree, see Trotter’s The English Novel in History and “The Politics of Adventure in the Early British Spy Novel,” and Woods, Neutral Ground. For background, see Hepburn; Snyder; Denning; and Wade.

[2] See John Adcock, “Ruth the Betrayer,” Yesterday’s Papers, 27 Feb. 2009 (accessed 13 Aug. 2016). “The London Library” version of the penny dreadful Guerrilla Spy is extremely rare; the author was, apparently, Henry C. Magruder (“Sue Munday”) of Kentucky.

[3] See Bold, “Secret Negotiations” 17.

[4] See Blackbeard, Bill and Justin Gilbert, “Peeps into the Past: A Detailed 1919 History of Bloods and Journals” (accessed 13 Aug. 2016).

[5] On invasion fiction, see Clarke’s seminal Voices Prophesying War and the more recent article by Hughes and Wood. See also Harry Wood’s blog “Island Mentalities” (accessed 13 Aug. 2016).

[6] For an overview of the secondary literature on and an analysis of Nihilist stage melodrama and hack fiction, see Vaninskaya’s “‘Truth About Russia.’” There is a large secondary literature on terrorism in late Victorian and Edwardian fiction, see: Melchiori; Wisnicki; O Donghaile; and Frank and Gruber. Glazzard’s Conrad’s Popular Fictions places Conrad in this context.

[7] Elsewhere in Wilde’s work one encounters the view that “spies are of no use nowadays. Their profession is over. The newspapers do their work instead” (An Ideal Husband in Major Works 447).

[8] There is an extensive literature on this subject. For a lively introduction, see Butterworth.

[9] See Porter 114-16 and passim.