Krista Lysack, “The Royal Charter Storm, 25-26 October 1859”

This essay considers the Royal Charter Storm, perhaps the most devastating weather event to occur in Britain in the nineteenth century, a gale that is named for the wreck of the Royal Charter steamship off the coast of North Wales and the subsequent drowning of most of its passengers and crew. Although this tragedy resulted in improvements in weather warning systems that contributed to the rise of modern forecasting, that is not the storm’s only legacy. In the aftermath of a parallel media storm, a host of reports ran in newspapers across the country in the days, weeks, and even months that followed, together producing a sense of this wide-ranging storm as a shared, national event. Among these reports was Charles Dickens’s account in All the Year Round, a striking portrayal of the losses associated with the wreck and an effort to ameliorate the suffering it had caused. Rather than predicting the weather, reports of the storm in the popular press turned to another kind of weather model of sorts, the retrospective work of memorializing and sympathy.

Judith L. Fisher, “Tea and Food Adulteration, 1834-75”

This essay examines the adulteration of tea in the contexts of free trade and the politics of empire. It contends that the importance of tea as a healthful, particularly British drink made the adulteration of the beverage a significant matter for social and moral concern. Adulterated tea was primarily from China and so was typed as “foreign” and unclean in contrast to tea imported from Assam, India, that was defined as “British” and healthy.

John M. Picker, “Threads across the Ocean: The Transatlantic Telegraph Cable, July 1858, August 1866”

This essay considers the significance of one of the signal technological developments of the nineteenth century—an event so signal that it happened twice. The transatlantic telegraph cable linking the Old World with the New was first successfully completed in August 1858, only to cease functioning within a month, and was permanently re-established in July, 1866, this time accompanied by the reappearance, with slight variations, of much of the verse and prose written to commemorate the original success, in what might be considered a case of canny cultural recycling. While the cable ultimately connected England and the United States, it only did so by way of Ireland and Canada, which is to say that this was very much an imperial project, one celebrated as reinforcing transatlantic ethnic and linguistic superiority in a mythology of Anglo-Saxonism that Victorians largely constructed and widely endorsed. As a way to approach this convergence of ideologies of progress, empire, language, and race, the essay focuses on what arguably was the critical aspect of the cable’s material composition, and considers, in general terms and in the specific literary case of Henry James, how the concept of insulation can help us to interpret representations of the cable and the transatlantic ties it extended.

Kristi N. Embry, “The Entente cordiale between England and France, 8 April 1904″

The Entente cordiale was a series of formal political agreements signed in 1904 that negotiated the peace between England and France. French for “warm understanding,” the Entente cordiale of 1904 settled more immediate disputes between England and France in Egypt, Morocco, and elsewhere in Africa. Perhaps more famously, the series of agreements signed in 1904 contributed to the harmonization of relations between the two countries in the twentieth and twenty-first centuries. But, as I show here, the Entente cordiale of 1904 also served as the culmination of a more informal—and precarious—entente that had slowly developed between the former enemies beginning in the 1830s and 1840s.

Marjorie Stone, “Joseph Mazzini, English Writers, and the Post Office Espionage Scandal: Politics, Privacy, and Twenty-First Century Parallels”

In 1844, an English radical MP affiliated with the Chartist movement petitioned the House of Commons, charging that Sir James Graham, Secretary of State for the Home Office, had secretly authorized the opening of the letters of exiled Italian nationalist and resident of London, Joseph Mazzini, spying upon their contents. The ensuing Post Office espionage scandal is a pivotal event in British and European history, represented—like Mazzini himself—from conflicting perspectives and shaping a host of subsequent developments. It provoked “anti-Graham” envelopes and parodies in Punch, intensified British sympathy for the Italian liberation and unification movement for which Mazzini was the principal theorist, and influenced British policy towards the 1847-49 revolutions in Italian states struggling for independence from Austrian overlords and autocratic Bourbon kings. The scandal and the networks it forged also shaped British party politics, Chartist international alliances, and emerging conceptions of rights to privacy and limits on state surveillance. Mazzini, revered as an apostle by many, was viewed as a dangerous subversive by many others, including the Pope and Prince Klemens von Metternich, Foreign Secretary to the Austrian Empire, later one of Henry Kissinger’s diplomatic models. As the scandal unfolded, evidence indicated that Graham and the Foreign Secretary Lord Aberdeen shared information from Mazzini’s letters with the Austrians, linking British espionage to the execution of the Bandiera brothers, Italian revolutionaries, in Naples in July 1844. This essay surveys diverse responses to Mazzini and the literary and cultural as well as the political repercussions of the 1844 scandal. Prominent English writers, notably Thomas Carlyle, came to Mazzini’s defence, especially indignant over violations of privacy, while others—including Robert Browning, Elizabeth Barrett Browning, George Meredith, Algernon Charles Swinburne, and George Eliot—went on to write works influenced by the charismatic, controversial Italian nationalist. An epilogue notes some of the 1844 event’s parallels with current controversies over communications hacking (WikiLeaks, the News of the World phone hacking) and appropriate limits on state secrecy and surveillance in the wake of 9/11, 7/7, anti-terrorism legislation, and the “rendition” of information and/or persons such as Canadian-Syrian Maher Arar to oppressive regimes by democratic countries.

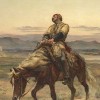

Zarena Aslami, “The Second Anglo-Afghan War, or The Return of the Uninvited”

The Second Anglo-Afghan War grew out of longstanding tensions between Russia and Britain over Britain’s prized colonial possession of India. In my account of the Second Anglo-Afghan War, I would like to emphasize two main themes. First, Afghanistan occupied an anomalous position in the British Empire. The British did not seek to colonize it or conquer it. Rather, they sought to install a sovereign who would be sympathetic to British interests, allow the British to control Afghan foreign policy, and forbid Russia from entering its borders. Second, by granting sovereignty to chosen leaders, British actions toward Afghanistan complicated the notion of sovereignty as such. The case of Afghanistan ought to remind us that it is extremely difficult to generalize how imperial power functioned across the nineteenth century and, moreover, that imperial power, in Afghanistan and other sites, was not homogeneous but rather could emanate from multiple empires at cross purposes over a single location.

Stephen Arata, “On E. W. Lane’s Edition of The Arabian Nights’ Entertainments, 1838″

The sequence of tales called in Arabic Alf Layla wa Layla was introduced to European readers by way of Antoine Galland’s enormously popular twelve-volume edition of Les mille et une nuits (1704-17). English translations of portions of Galland’s edition appear as early as 1706, and tales designated as belonging to the Arabian Nights circulated in close to one hundred separate editions published in Great Britain before 1800, all of them derived in some way from Galland. Galland had drawn from numerous sources—oral, manuscript, and print—and the provenance of many of the tales he translated was murky at best. The first efforts to produce a definitive Arabic edition of Alf Layla wa Layla date to the first quarter of the nineteenth century. Lane presented his edition as the first in English to be based on the recent Arabic editions rather than on Galland. Lane also took the unconventional view that The Arabian Nights were to be read not for their literary or entertainment value but for the historical and ethnographic light they throw on Arabic, specifically Egyptian, “life and customs and manners.” His copious and often quite lengthy annotations of the tales and his modernized system of transliteration, as well as his unapologetic pedantry, impressed and alienated his first readers in about equal measure.

Robert David Aguirre, “Mexico, Independence, and Trans-Atlantic Exchange, 1822-24”

This entry connects the Spanish American independence movements of the 1820s to the emergence of new pathways of trans-Atlantic cultural exchange. It shows that Britain’s political recognition of the new republics opened a two-way channel in which things, commodities, persons, and ideas flowed back and forth, affecting culture and politics on both sides of the Atlantic. Focusing particularly on Britain’s relations with Mexico, this entry examines key moments in the immediate British response to Spanish American independence.

Julie Codell, “On the Delhi Coronation Durbars, 1877, 1903, 1911”

This essay explores the three Delhi Coronation Durbars and their relationship to topics of spectacle, imperial policy, visual culture, modern media, and Indian and British responses to these events.

Antoinette Burton, “On the First Anglo-Afghan War, 1839-42: Spectacle of Disaster”

This essay surveys representations of the first Anglo-Afghan campaign (1839-42) in an effort to recast the narrative of the war so that it accounts for the variety of native actors in the war and in the geopolitical crises leading up to it. The “Great Game” may have been a “tournament of shadows” between the British and the Russians, but it was entangled by both local dynastic conflicts and a challenging, even insurgent, physical terrain as well. Though the British officially won the war, Afghanistan was hardly secure either during the occupation or in the decades that followed. In that sense, the first Anglo-Afghan war presaged a century of precarious imperial power on the frontier of the Raj.