Abstract

Magazine Day refers to the last day of every month when wholesale booksellers in London received the new monthly serial publications and prepared them for distribution. The monthly event determined the rhythm of the publishing industry for much of the nineteenth century and thus reflects the growing importance of serials to the nineteenth-century book trade.

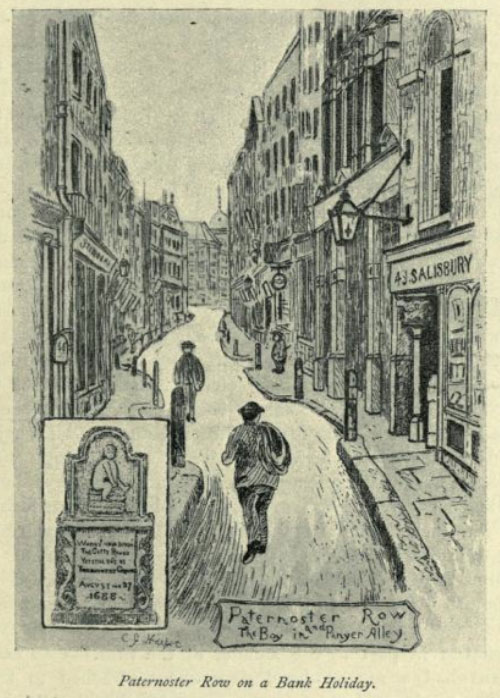

Figure 1: The book trade on Paternoster Row as illustrated in _The Penny Magazine_ of the Society for the Diffusion of Useful Knowledge (31 Dec. 1837)

Of course, the development of Magazine Day had everything to do with the rise of serial publication in the nineteenth century—a phenomenon that had its origins in the previous century; moreover, from about the 1820s, the monthly publication cycle for serials and periodical titles dominated the trade (Brake, “Magazine Day” 390).[2] Magazine Day met the needs of publishers and retail booksellers, but in the process became something of an institution. Testifying to the fact, in 1854 poet and critic George Gilfillan declared, “It is difficult now even to conceive of Britain without a ‘Magazine-day’” (97). In the public mind, Magazine Day came to stand for the delights of monthly periodicity, which in the age of Charles Dickens and William Makepeace Thackeray were abundant. By about the 1870s, however, the importance of Magazine Day had diminished. Weekly serials had begun to draw a larger middle-class audience, and the sheer volume of periodical literature published at all times in the month ensured that every day was a kind of Magazine Day.

*****

As multiple accounts make clear, the work associated with Magazine Day was considerable and of necessity began some days earlier. As soon as booksellers’ monthly orders arrived, publishers strove to assemble already available stock from their own wares and those of rival booksellers, so these publications could be mailed out with the new serials in a single package. On the “late night” before Magazine Day, so-called because of the late hours required, the recently arrived orders were tallied and invoiced in preparation for the next day’s collection and packing of books and magazines. Advance work of this sort was essential, given the volume of print being distributed. In his history of the trade, Joseph Shaylor, who served as a director of Simpkin, Marshall, and Co., refers to a circular sent to country booksellers in 1827 requesting earlier submission of orders, “as in consequence of the very increased number of periodicals it was impossible to send off their parcels in proper time” (186; Raven 246). According to Shaylor, this plea had some effect. But the pace of production and demand quickened as the century went on. A news item on the periodical trade in 1817 marveled over the figure of “fourscore periodical works” readied for Magazine Day (Cambridge Chronicle 4). Twenty years later, James Grant estimated over two hundred periodicals and a total of 400,000 items were sent out from the Row (83). Fifteen years after that, the figure had ballooned to two and a half million items (“Business” 454).

The business was of course time-sensitive because readers and the retail trade that supplied them were eager to receive the new serials and magazines on the first day of the month. Grant comments that “the great contest among the trade is, who shall be able to supply their customers earliest,” and notes that by noon on Magazine Day the new periodicals were already displayed in booksellers’ shops across London (74-75). Country customers may have received their reading matter within a week or as soon as the following day, depending on their distance from the capital and the mode and speed of travel (Raven 61, 229, 323), but their expectations were equal to those of their metropolitan counterparts. According to Charles Manby Smith’s account of Magazine Day published in Chambers’s Journal of Popular Literature (1855), the publisher “cannot afford the risk of a moment’s avoidable delay” when dealing with the orders of provincial booksellers, “each of whom would think there was a design to ruin him, if his parcel did not arrive on the first of the month” (402).

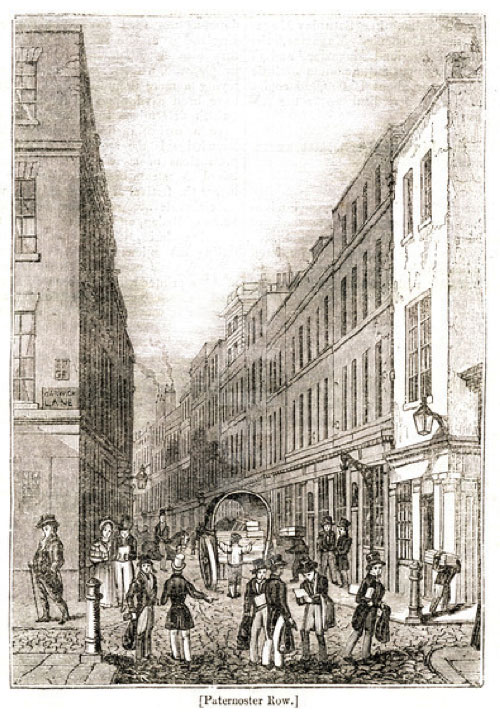

These pressures certainly contributed to the frenetic activity associated with Magazine Day. In his account, Smith describes the monthly transformation of the Row from a state of repose to one of incessant activity, likening it to “an Egyptian pot of vipers” (402). The intrepid reader is invited to witness a complicated dance of “figures darting to and fro, and across and back again—with bulging sacks on shoulder—with paper-parcels and glittering volumes grasped under each arm—and with piles of new books a yard high resting on clasped hands” (Smith 403). Described here is the work of the bookseller’s collector, an urban type recognizable by his book-filled canvas bag (fig. 2). The collector’s task was to travel down the Row and across the city to other publishing houses in search of the many publications not in stock at his own house. In other words, each wholesaler served simultaneously as a source of supply and demand, engaging in transactions with other wholesalers and even retailers in an effort to fulfill all orders. As Smith explains, every publisher becomes “a quarry of more or less importance to fifty other publishers, whose agents and collectors are goading him on all sides with eager and hurried demands” (403).

The bookseller’s collector was an appropriately picturesque figure, and his interactions with clerks provided colorful dialogue in contemporary accounts. Henry Curwen in his History of Booksellers (1874) calls the collector “suspicious in general appearance” (418). At the same time the collector is shown as a savvy character, an expert in his highly specialized trade: “Bag in hand he rushes in hot haste all over London, and with an impudent tongue and a pair of brawny shoulders, thrusts himself to the front place before each publisher’s counter” (418). The author of “Business of a London Wholesale Bookseller” (1852) likewise emphasizes the expertise of the collector, in this case the fancifully-named “Shiney.” As the journalist struggles to keep up, “Shiney” is “diving under horses’ heads, dashing over perilous crossings . . . shouldering loungers aside . . . darting into dozens of shops . . . paying in a hurry; scarcely counting the change” (“Business” 453). Within the shops, the scene is no less hurried, as collectors crowd the counters, and the booksellers’ clerks rush forward with stacks of publications. A letter appearing in the Tatler from 28 March 1832, tries to convey the aural experience, as clerks and collectors shout out orders: “‘Gent’s. Mag., Blackwood’s Mag., Fraser’s Mag., London’s Mag., Monthly Mag., Evan. (pro-Evangelical) Mag., Baptist’s Mag.,’ &c &c. It is a very Bable [sic] of Mags. Fancy about fifty mouths bawling out at once at the very highest pitch of their ‘most sweet voices’ in a confined room!” (“Anticipations”). James Grant adopts the Babel comparison also, noting that “such unintelligible jargon . . . is kept up incessantly by fifteen or twenty persons at once” (81). The noise and bustle, the fast-paced action, and the peculiar characters made Magazine Day a congenial subject for journalists working within the tradition of the urban sketch.

Even if they were not writing about Magazine Day, authors had reason to anticipate it, for on that day their fates—in the form of critical notices or the publication of a submission—would be revealed. Grant includes the arrival of anxious authors and hopeful contributors in his depiction of Magazine Day, treating their early morning appearance at the booksellers’ premises as an established part of the monthly ritual: “Their anxiety to ascertain their doom is, in such cases, so intense, that they will rather walk from the most distant parts of London to the Row—the magazines being there first seen—than wait for two or three hours till brought to them” (85). A facetious article in an 1836 issue of Blackwood’s Lady’s Magazine devotes itself to the ambitions of the amateur literati. These would-be contributors are mocked for venturing out on Magazine Day to get a glimpse of the new periodicals: “At length Magazine Day has arrived—that day which seemed as if it never would come to the scribbling ephemera, who, having posted some effusions to the editor, look forward with palpitating hearts to the moment which decides their literary fate” (“Pen and Ink Outlines” 78). One such failed “scribbler” is pictured “breathing imprecations against the periodical” that has rejected his lyric contribution. But even for professional authors like Dickens, Magazine Day could be a source of anxiety, associated as it was with success or failure of a new literary venture. For his part, Dickens liked to be out of London on Magazine Day. As John Forster explains, “having been away from town when Pickwick’s first number came out, he made it a superstition to be absent at many future similar times” (85). How well the first number of a new serial sold provided an early indication of its success.

The origins of Magazine Day in the trade are difficult to locate precisely. As James Raven indicates, the publication of monthly magazines and part-issues had begun to affect the rhythms of distribution by the late-eighteenth century (246). Charles Rivington III of the esteemed Rivington publishing firm mentions “Magazine Night” regularly in his diary, which he kept from 1778 to 1782 (Raven 246). It is unclear how long this practice had been in place before Rivington recorded it. We do know that the publication of the Gentleman’s Magazine in 1731 inaugurated a period of growth in the serial market (Raven 130). The numbers tell the story of this expansion: whereas fifteen periodical magazines and reviews were published in London in 1760, that number had risen to thirty in 1790 (Raven 246). Production and demand only intensified in the first decades of the nineteenth century, the period when writers and publishers first began to conceive of a mass reading public (Butler 145; Stewart, Romantic Magazines 1-2). Although newspapers are also included in the figures, the total number of new periodical titles published in the period rose swiftly: between 1800 and 1809, 154 new titles were published; between 1810 and 1819, 265 new titles; and between 1820 and 1829, 599 titles (Eliot 84, table E4). Contrasting the periodical with the book trade in these same decades, Kathryn Sutherland notes “an unprecedented explosion in all kinds of magazine, review, and journal publication” (681). The phenomenon was widely remarked in contemporary accounts too, as for example in William Stevens’s discussion of trends in periodical publication in Blackwood’s in 1824: “Fifty years since, readers of such works were content with one or two in a month; the number at present published weekly, monthly, and quarterly, we shall not stop to calculate. . . . Their vast increase, and the constant additions which are almost daily making to their number, are too notorious to require proof or illustration” (519). The “vast increase” of periodicals had an obvious impact on how Magazine Day was experienced in the trade.

What we might call the growing cultural relevance of Magazine Day, however, can be linked to the appearance of a group of new magazines in the 1810s and 1820s. David Stewart calls the ten years after the end of the Napoleonic wars the “age of the magazine,” referring to the emergence of a group of monthly magazines addressed to a diverse middle-class audience and characterized by a miscellaneous content of essays, reviews, fiction, and poetry (Romantic Magazines 1). (On the new monthly magazines, see also Linda K. Hughes, “On New Monthly Magazines, 1859-60.″) Among these magazines, we can include the New Monthly (1814), Blackwood’s (1817), the London Magazine (1820), the New European (1822), and, coming slightly later, Fraser’s (1830), the Metropolitan (1831), and Tait’s Edinburgh Magazine (1832). Stewart singles out Blackwood’s as marking the shift to a new style of magazine writing, markedly different from that of the eighteenth century (Romantic Magazines 4). While the paradigmatic Gentleman’s Magazine imagined its ideal reader as a leisured gentleman engaged in the pursuit of knowledge broadly conceived, Blackwood’s projected a readership craving entertainment and in pursuit of cultural capital (Stewart, Romantic Magazines 18-23). In 1824, William Stevens characterized earlier publications as staid and tiresome, their pages devoted to “some common-place topic, such as anger, pride, the shortness and vanity of human life, or those of a similar nature, with just as much infusion of intellect as was necessary to give the symptoms of vitality to the words, and . . . written in a most loose, feeble, and incorrect style” (519-20). The new monthly magazines, in contrast, featured a diverse array of papers “displaying infinitely more ability, treating of a much greater variety of subjects” and directed to an ambitious audience eager for information and improvement (521).

Also characteristic of the new monthlies—and obvious from Stevens’s self-congratulatory account—is an intense self-consciousness. Again as David Stewart explains, the magazines repeatedly demonstrated an awareness of themselves and their readers as participants in a larger print culture (“P. G. Patmore’s” 207-08). In fact, it is this phenomenon (among others) to which Thomas Carlyle refers in “Characteristics” when he asserts: “Never since the beginning of Time was there, that we hear or read of, so intensely self-conscious a Society” (19).[3] In the essay, published in the Edinburgh Review in 1831, Carlyle decries “the diseased self-conscious state of Literature” (24). Carlyle was concerned about the displacement of books by reviews, which at their best could only be a derivative kind of literature. According to Lee Erickson, the idea of a “Review of Reviews” was so troubling for Carlyle because it suggested “the reproductive multiplication of the publishing marketplace” (113)—the mise en abyme of print culture. Although Carlyle took a grim view, he was right about the periodical’s self-reflexivity—the paradigmatic example of which is the representation of Magazine Day. Accounts of Magazine Day, while they may have been informative or enjoyable or both, fundamentally served to promote magazine reading by depicting it as a cultural ritual.

The promotional aspect of these accounts emerges more clearly in the journalism of Charles Knight. Knight, whose Penny Magazine would help bring cheap literature to the masses, claims in his memoir to be the originator of periodical criticism in the newspaper: these columns appeared in the Guardian weekly newspaper, which he edited, under the heading “Magazine Day” (263). The first installment, published on 3 March 1821, includes with its overview of a handful of periodicals an enthusiastic plunge into the “agreeable . . . bustle of Paternoster Row on the last day of the month” (263). The perspective is privileged, yet open to all:

We delight, on these memorable mornings, to lounge through the narrow approaches of Ave-Maria or Warwick Lanes, and then to make a dead stop in the Paradise of Publishers—to hear the hum of the great hive of literature—to see its bees going forth in search of, or returning with, their spoils. As the dusky porter . . . brushes past us, we delight to speculate upon the component parts of his burden—to estimate the relative proportions of Blackwoods and Baldwins, of Monthlies (Old and New), of Gentleman’s and Ladies’, of Belle Assemblies and Evangelicals. (264)

More than an introduction to the latest magazines, Knight’s article provides entry into a vibrant magazine culture. But Knight’s narrative also functions as an effective marketing strategy, transforming periodical publication into an exciting event. A sure indication of the value of this publicity is Knight’s comment that after the first of these articles appeared, publishers began supplying him copies of their magazines “without giving me the trouble of a journey to Paternoster Row” (264-65). Self-reflexivity is good for business: periodical criticism served the important function of generating desire for a commodity with an expiration date.[4] Moreover, it accustomed readers to the cyclical rhythm of anticipation, acquisition, and enjoyment that characterizes periodical publication.

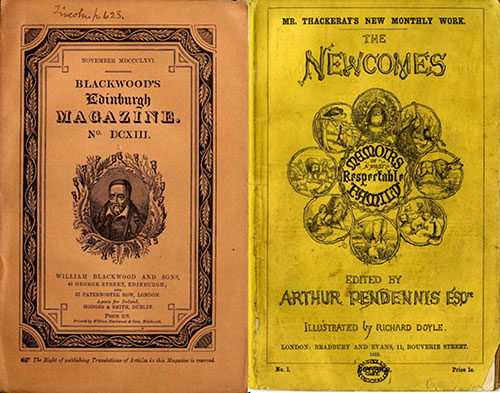

Although my focus up to this point has been on magazines, we cannot overlook the role other forms of publication, especially serialized fiction, played in the periodical market. Laurel Brake, emphasizing the continuity between journalism and literature in the nineteenth century, reminds us that new books and part-issues were as prevalent as magazines in the monthly distribution cycle (Print in Transition 30) (see fig. 3). In fact, the growth of the market for periodical literature coincided with the increased production of serial fiction and non-fiction in monthly parts. Already by the end of the eighteenth century, publication of books in part-numbers had become a major part of the industry so that, according to James Raven, “Paternoster Row numbers included many rival family bibles, encyclopedias, Shakespeares and histories of England and the world” (247-48). Publishers seized on serialization as a way to generate excitement for journal titles, and publishing in part-issues ensured a relatively reliable income stream. For their part, readers of serials benefited from the cheaper prices and the more flexible distribution methods adapted for newspapers and magazines, such as the postal service, railway carriage, and individual peddlers (Law and Patten 147). Serialized fiction and other part-issue publications thus contributed to the dominance of the monthly cycle of publishing and reading, which according to Graham Law and Robert Patten held sway between the 1830s and 1850s (148).

Figure 3: Paper covers for issues of _Blackwood’s Magazine_ (Nov. 1866) and the first number of _The Newcomes_ (Oct. 1853) remind us of the similar format of magazines and serials

It is unlikely, however, that Magazine Day would have become as culturally central as it did without Dickens’s unrivalled success with the monthly serial form. In a review of the volume publication of Great Expectations in 1861, E. S. Dallas reminisces about the “hazardous experiment” of publishing fiction in monthly parts and notes that “Mr. Dickens led the way” in what would become an important development in the novel form (6). Similarly, a review of Dickens’s Christmas books in the Sheffield and Rotherham Independent asserts that before Pickwick Papers, “[i]llustrated novels issued in monthly parts, were perhaps unheard of” (“Charles Dickens”). The review explicitly links the success of Pickwick to the “greatly increased . . . importance” of Magazine Day (“Charles Dickens”). Pickwick Papers was of course not the first novel in parts, but its popularity transformed print culture. By the end of its run in 1837, nearly 40,000 copies were printed (Patten 68). Other novels by Dickens performed equally well or better: sales of Nicholas Nickleby in 1838-39, for instance, sold up to 50,000 copies of each part-number (Patten 99). As many scholars have noted, the publication of serialized fiction in monthly installments was only profitable in the case of the most popular writers; thus, it was a relatively short-lived phenomenon (Sutherland, Victorian Fiction 86; Law 18). (See, for example, Richard Menke, “The End of the Three-Volume Novel System, 27 June 1894.″) Still, this mode of publication left its mark, not only helping to establish the habit of serial reading in various formats and time cycles, but also turning Magazine Day into a highly anticipated public event.

Indeed, part of the appeal of Magazine Day for readers was the experience of anticipation created by periodicity. As numerous accounts suggest, readers eagerly awaited the appearance each month of the new magazines and continuing serials. An article from an issue of The Biblical Review and Congregational Magazine in 1846 implicitly compares the excitement before Magazine Day to that preceding the visit of old friends: “The reading rooms in the great cities and the book clubs in the quiet country towns and the fireside circles of numberless happy English families are all in anxious expectancy of the London parcel that brings down their several favourites” (“Periodical Literature” 391). A review of Anthony Trollope’s Can You Forgive Her? in The Month (1865) similarly evokes the scene of a highly anticipated meeting of old friends, as readers look forward to issues of a serialized novel:

Domestic politics may be tranquil, and the current of family life may run on with the happiest monotony: but there is Mr. Dickens, and Mr. Trollope, and Mr. Wilkie Collins, and a number more; and it gets at last to be three weeks or so since we heard any thing about our Mutual Friend or Lily Dale; and then there is the great Armadale question, and what is to become of Cynthia and Molly Gibson; and in a few days more we shall have news. (“Mr. Trollope’s Last Novel” 319)

In both excerpts, the special role of the periodical seems to lie in its status as both old and new, routine and familiar.

The monthly periodical also prescribed a certain rhythm: a period of “quiet” expectation and “monotony” followed by a burst of activity; the waiting is pleasurable because everyone knows the exact date when the wait is over. Leigh Hunt enthuses over this last point in his 1832 editorial on Magazine Day in the Tatler: “Only think of the ingenuity of making pleasure periodical; fixing a date when the anxious mind shall have an object to divert it.” What so many of these accounts suggest is the rarity of new cultural objects and entertainment in the daily lives of most Britons in the early nineteenth century. This rarity made Magazine Day special, like a holiday devoted not to traditions of the past but to the innovations of the present—whether these were the railways that enabled literature to reach across the country or authorial fecundity that kept inventing new stories to delight readers. Commenting on the progress of periodical literature in 1854, George Gilfillan reflects, “What dreary Firsts of the Months must those of our forefathers have been, when as yet our ‘Ebonies,’ [i.e., Blackwoods] and ‘Hoggs’ and ‘New Monthlies’ and ‘Cookes,’ . . . were unopened and undreamed of” (97). Periodical literature gave shape to time in the nineteenth century, and that shape, as Margaret Beetham has explained, conformed to the demands of a modern industrial society (28).

While anticipation was one of the pleasures associated with the periodical, we must not overlook the importance of periodicity as a means for readers to experience connection—connection with authors, memorable characters, and other readers. As Linda Hughes and Michael Lund have suggested, the extended nature of serial reading helped forge a “community of readers” (10). Not only could readers exchange ideas about an unfolding serial, but also they could read newspaper and magazine reviews of part issues, which reinforced the sense of serial reading as a shared experience (Hughes and Lund 10). The idea of the serial as a cultural product held in common was reinforced by the belief (true to a certain degree) that readers received and read installments at the same time. Readers of a serial publication, no matter where they lived, could feel connected with others and in tune with the rhythms of Paternoster Row. For instance, Mary Russell Mitford, situated in a village quite removed from London, was able to share in the Pickwick buzz of 1837; in a letter to an Irish correspondent, she marvels that a person exists who has yet to receive the “news”: “So you have never heard of the Pickwick Papers! Well, they publish a number once a month and print 25,000. . . . I did think there had not been a place where English is spoken to which ‘Boz’ had not penetrated” (Collins 36). Dickens extended the reach of the imagined community, but magazine writers had been encouraging readers to recognize themselves as part of such a community at least since the 1820s. As Stewart demonstrates in his discussion of periodical essayist George Patmore, “Even for an audience cut off from the metropolitan centre of the nation, the magazine . . . present[ed] a unified cultural experience” (“P. G. Patmore’s” 207). Patmore contributed to the assimilative project, according to Stewart, by publishing (among other essays) his “Letters to Country Cousins” series in the New Monthly Magazine (1824-25) (207). The “Letters” are remarkable for the way they make the metropolitan experience a shared experience, leading “country cousins” on perambulations through the streets beyond the officially sanctioned, “visitable localities” of the West End (216). Patmore in his avuncular persona even passes “the dreary defile of Paternoster Row,” which he does not enter but nonetheless identifies as “that dark domain of the Booksellers, from which issue forth (like the Winds from the black cave of Eolus) those winged messengers of the national mind which make their way to the four quarters of the Globe” (225).

Patmore writes of the “national mind” issuing out from the Row, and in one sense the metaphor fittingly describes the experience of a modern distribution network. The idea of shared knowledge widely dispersed is part of the magic evoked by Magazine Day. The same idea is suggested by Charles Manby Smith in his 1855 depiction of periodical distribution (again by means of “wings”). On the appointed day, Smith writes, “some million or so of copies of the latest productions of the press have taken to themselves wings of steam, and are all flying from London, as a common centre, to all parts of the realm; and before to-morrow night the greater portion of them will be affording to the reading public their monthly literary treat” (404). Both writers imagine periodical reading as a unifying experience, although by using the language of center and periphery, they overemphasize the role of authors and publishers in creating a reading community. The national mind does not emerge whole from Paternoster Row, rather it emerges from synchronized reading—the participation of large numbers of readers in an imaginatively shared experience.

The predominance of monthly periodicity was, however, relatively short-lived, and the weekly Graphic in 1887 refers to “Old Magazine Day” as if it were some forgotten custom. Magazine Day remained a significant day for the trade well into the 1870s, but it is true that by that time weekly news miscellanies and magazines were beginning to challenge the monthly magazines as the dominant serial form (Law 24). As Graham Law argues, the surge of new monthly literary magazines in the 1860s (such as the Cornhill and Macmillan’s) has tended to obscure a significant shift in the publishing industry away from monthly and toward weekly serial publication (24). (See also Graham Law, “22 May 1891: Ouida’s Attack on Fiction Syndication.”) The abolition of the “taxes on knowledge” in the 1850s and 1860s played an important role in this shift, by encouraging the growth in numbers of periodical titles and in their frequency of publication (Law 30-32). The serialized novel issued in monthly parts also lost ground to the literary miscellanies, which for a price similar to that of the shilling number offered “only slightly shorter episodes from a couple of original novels, together with a cornucopia of non-fictional features” (Law and Patten 162). This is not to say that readers in the second half of the century rejected monthly publication, just that they had a wider range of choice in reading material than their parents and grandparents. A variety of publications appealing to every taste and interest were published at intervals of a day, week, month, quarter, and year.

The sheer volume of periodicals not only afforded readers more choice but also kept booksellers busy nearly every day of the month. As James Glass Bertram notes in his autobiography from 1893, although Magazine Day had been a “sacred institution” during his professional life, “[a]t present every day may be called a ‘Magazine day’” (147, 148). This new state of affairs he attributes to the rapid growth of the industry: “the circulation of several of the magazines now published is individually greater than the aggregate of all the magazines in existence fifty years ago; so that a fixed day for magazine distribution would be an impossibility” (148). The increased production of print required a faster tempo for distribution; moreover, the crowded market encouraged publishers of monthly serials to issue them earlier and earlier. An article in the Birmingham Journal on 7 September 1867, comments on the publication of Tinsley’s Magazine and the Cornhill weeks before the end of the month and adds facetiously, “we shall soon find our October magazine come in with the partridges on September the first” (“Literature”). Despite the advantages of a thriving periodical market, retail booksellers in particular struggled to adapt to more flexible and frequent publication schedules. The bookseller Edward J. Blake of ![]() Newcastle appealed in March 1880 to the editors of the Publishers’ Circular to “induc[e] the publishers in London and elsewhere to issue their serials on or about the same day in each month” (206). He notes the added trouble and costs of multiple deliveries from London, as well as customer complaints resulting from an irregular publication schedule. The bookseller T. Thatcher of

Newcastle appealed in March 1880 to the editors of the Publishers’ Circular to “induc[e] the publishers in London and elsewhere to issue their serials on or about the same day in each month” (206). He notes the added trouble and costs of multiple deliveries from London, as well as customer complaints resulting from an irregular publication schedule. The bookseller T. Thatcher of ![]() Bristol similarly complains to the Bookseller in March 1894 of the “growing evil” of multiple, “made to order” Magazine Days; “It should be remembered,” he continues, “that we have to deliver magazines” (207). The complaints of Blake, Thatcher, and presumably other retailers derived from practical concerns relating to the changes in the serial market.

Bristol similarly complains to the Bookseller in March 1894 of the “growing evil” of multiple, “made to order” Magazine Days; “It should be remembered,” he continues, “that we have to deliver magazines” (207). The complaints of Blake, Thatcher, and presumably other retailers derived from practical concerns relating to the changes in the serial market.

A rather different response to these changes came from authors and readers for whom Magazine Day represented an idyllic past. This examination of Magazine Day thus ends on a retrospective note—with nostalgia for lost periodical pleasures. A contributor to St. James’s Magazine in 1875 recalls the days “between thirty and forty years ago” when “‘magazine day’ . . . [was] anxiously anticipated and heartily welcomed by press and public” (“Magazines” 376). “Alas!” continues the writer, “where are they now . . . those pleasant memories of our youth?” (“Magazines” 376). Some years later in 1898, Laura Hain Friswell, in the biography of her father, the journalist James Hain Friswell, recalls her parents’ enthusiasm on receiving the monthly installments of The Newcomes. For her generation, however, “literature and all things are so evanescent” that enthusiasm has been replaced by ennui; she appeals to her audience of peers rhetorically: “Should we keep up our interest in a story for nearly two years, and could any one feel excited over magazine day now?” (Friswell 50). The nostalgia for a more august literary landscape was felt most keenly by a belated author like Henry James. In Notes of a Son and Brother (1914), he reminisces about the monthly arrival of the Cornhill and The Newcomes and about the “more sovereign periodical appearances” that belonged to the era of Thackeray and Dickens (21). In James’s telling, Magazine Day mattered because it promised to bring literary entertainment of a superior sort to readers across the nation. The monthly arrival of The Newcomes made a “difference”: “I witnessed . . . the never-to-be-equalled degree of difference made, for what may really be called the world-consciousness happily exposed to it, by the prolonged ‘coming-out’ of The Newcomes, yellow number by number” (James 22). For James, such collective enjoyment was civilized, proceeding as it did at a reasonable pace and free from the kind of distraction created by a saturated literary market. Readers in the early twentieth century had no such luxury, according to James; his was “a generation so smothered in quantity and number that discrimination, under the gasp, [had] neither air to breathe nor room to turn around” (20). On the one hand, such nostalgia could be dismissed as a sign of advanced age or even as an inevitable condition of modernity. On the other hand, the declining significance of Magazine Day represented a real loss—the loss of a shared conception of time and of community that would have to be reimagined in a new media landscape. For a brief period, Magazine Day imposed a synchronized periodicity that, in binding readers to the calendar, bound them to each other.

published June 2015

HOW TO CITE THIS BRANCH ENTRY (MLA format)

Allen-Emerson, Michelle. “On Magazine Day.” BRANCH: Britain, Representation and Nineteenth-Century History. Ed. Dino Franco Felluga. Extension of Romanticism and Victorianism on the Net. Web. [Here, add your last date of access to BRANCH].

WORKS CITED

“Anticipations of Magazine Day among ‘The Trade.’” Tatler 490 (28 Mar. 1832): [297]. British Periodicals. Web. 17 June 2014.

Beetham, Margaret. “Towards a Theory of the Periodical as a Publishing Genre.” Investigating Victorian Journalism. Ed. Laurel Brake. New York: St. Martin’s, 1990. 19-32. Print.

Bertram, James Glass. Some Memories of Books, Authors, and Events. Westminster: Archibald Constable and Company, 1893. Google Books. Web. 17 June 2014.

Blake, Edward J. Letter. Publishers’ Circular 16 Mar. 1880: 206. Nineteenth-Century Serials Edition. Web. 29 Dec. 2014.

Brake, Laurel. “Magazine Day.” Dictionary of Nineteenth-Century Journalism. Ed. Laurel Brake and Marysa DeMoor. Ghent: Academia and British Library, 2009. 390. Print.

—. Print in Transition: Studies in Media and Book History. Houndmills: Palgrave, 2001. Print.

“Business of a London Wholesale Bookseller.” Anglo-American Magazine 1 (1852): 452-54. HathiTrust. Web. 18 Mar. 2015.

Butler, Marilyn. “Culture’s Medium: The Role of the Review.” The Cambridge Companion to Romanticism. Ed. Stuart Curran. New York: Cambridge UP, 1993. 120-147. Print.

Cambridge Chronicle and Journal 5 Sept. 1817: 4. British Newspaper Archive. Web. 18 Mar. 2015.

Carlyle, Thomas. “Characteristics.” The Works of Thomas Carlyle. Rpt. of The Centenary Edition. Vol. 28. New York: AMS, 1969. 1-43. Print.

“Charles Dickens and His Christmas Books.” Sheffield and Rotherham Independent 6 Jan. 1849: 6. British Newspaper Archive. Web. 15 July 2014.

Collins, Philip, ed. Dickens: The Critical Heritage. London: Routledge, 1971. 35-36. Print.

Curwen, Henry. A History of Booksellers, the Old and the New. London: Chatto and Windus, [1873]. Google Books. Web. 17 June 2014.

[Dallas, E. S.] “Great Expectations.” Times 17 Oct. 1861: 6. Times Digital Archive, 1785-1985. Web. 15 March 2015.

Eliot, Simon. Some Patterns and Trends in British Publishing, 1800-1919. London: Bibliographical Soc., 1994. Print.

Erickson, Lee. The Economy of Literary Form: English Literature and the Industrialization of Publishing, 1800-1850. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins UP, 1996. Print.

Forster, John. The Life of Charles Dickens. Vol. 1. London: Dent, 1969. Print.

Friswell, Laura Hain. James Hain Friswell: A Memoir. London: George Redway, 1898. Internet Archive. Web. 29 Dec. 2014.

Gilfillan, George. “Prospective Periodical Literature.” Hogg’s Instructor 3 (1854): 97-105. HathiTrust. Web. 18 July 2014.

Grant, James. Travels in Town. Vol. 2. London: Saunders and Otley, 1839. Google Books. Web. 3 June 2014.

Hughes, Linda K. and Michael Lund. The Victorian Serial. Charlottesville: UP of Virginia, 1991. Print.

[Hunt, Leigh.] “The First of the Month.” Tatler 442 (1 Feb. 1832): [105]. British Periodicals. Web. 17 June 2014.

James, Henry. Notes of a Son and Brother. New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1914. Google Books. Web. 30 Apr. 2015.

Jones, Linda Bunnell. “James Grant on Magazine Day.” Victorian Periodicals Review 7.1 (1974): 10-11. JSTOR. Web. 3 June 2014.

Knight, Charles. Passages of a Working Life during Half a Century. Vol. 1. London: Bradbury and Evans, 1864-65. Lord Byron and His Times. Center for Applied Technologies in the Humanities. Virginia Tech. Web. 18 July 2014.

Law, Graham. Serializing Fiction in the Victorian Press. New York: Palgrave, 2000. Print.

Law, Graham and Robert L. Patten. “The Serial Revolution.” The Cambridge History of the Book in Britain. Vol. 6. Ed. David McKitterick. Cambridge: Cambridge UP, 2009. 144-71. Print.

“Literature, Science, and Art.” Birmingham Journal 7 Sept. 1867: 7. British Newspaper Archive. Web. 15 Mar. 2015.

“Magazines and Magazine Writers.” St. James’s Magazine 3.1 (Apr. 1875): 375-81. British Periodicals. Web. 17 June 2014.

“The Makers, Sellers, and Buyers of Books.” Fraser’s 45 (June 1852): 711-24. HathiTrust. Web. 18 Mar. 2015.

“Mr. Trollope’s Last Novel.” The Month: A Magazine and Review 3 (1865): 319-23. Google Books. Web. 25 Sept. 2014.

“Old Magazine Day.” Graphic 13 Aug. 1887: 182. Print.

Patten, Robert L. Charles Dickens and His Publishers. Oxford: Oxford UP, 1978. Print.

“Pen and Ink Outlines: The First of the Month.” Blackwood’s Lady’s Magazine 1 (1836): 78-79. Google Books. Web. 18 Mar. 2015.

“Periodical Literature.” The Biblical Review and Congregational Magazine 1 (1846): 391-393. Google Books. Web. 29 Dec. 2014.

Raven, James. The Business of Books: Booksellers and the English Book Trade, 1450-1850. New Haven: Yale UP, 2007. Print.

Roberts, William. The Book-Hunter in London. Chicago: A. C. McClurg, 1895. Google Books. Web. 17 June 2014.

Shaylor, Joseph. The Fascination of Books. New York: G. P. Putnam’s Sons, 1912. Google Books. Web. 17 June 2014.

[Smith, Charles Manby.] “Paternoster Row and Magazine Day.” Chambers’s Journal of Popular Literature 78 (30 June 1855): 401-04. ProQuest. British Periodicals. Web. 17 June 2014.

[Stevens, William.] “On the Reciprocal Influence of the Periodical Publications, and the Intellectual Progress of the Country.” Blackwood’s Edinburgh Magazine 16 (Nov. 1824): 518-28. HathiTrust. Web. 17 June 2014.

Stewart, David. “P. G. Patmore’s Rejected Articles and the Image of the Magazine Market.” Romanticism 12.3 (2006) 200-11. Project Muse. Web. 29 Dec. 2014.

—. Romantic Magazines and Metropolitan Literary Culture. New York: Palgrave, 2011. Print.

Sutherland, John. Victorian Fiction: Writers, Readers, Publishers. New York: Palgrave, 2006. Print.

Sutherland, Kathryn. “British Literature, 1774-1830.” Cambridge History of the Book in Britain. Vol. 5. Ed. Michael F. Suarez, SJ, and Michael L. Turner. Cambridge: Cambridge UP, 2009. Print.

Thatcher, T. Letter. Bookseller 7 Mar. 1894: 207-08. HathiTrust. Web. 29 Dec. 2014.

RELATED BRANCH ARTICLES

Ina Ferris, “The Debut of The Edinburgh Review, 1802″

Linda K. Hughes, “On New Monthly Magazines, 1859-60″

Graham Law, “22 May 1891: Ouida’s Attack on Fiction Syndication”

Richard Menke, “The End of the Three-Volume Novel System, 27 June 1894″

ENDNOTES

[1] An article published in the May 1852 issue of Fraser’s on pricing in the book trade also mentions seven wholesale houses in London, while the number of retail booksellers in the city is estimated between six and eight hundred (“The Makers, Sellers, and Buyers of Books” 723).

[2] The entry on “Magazine Day” in the Dictionary of Nineteenth-Century Journalism served as an obvious starting point for this essay, as did Linda Bunnell Jones’s short article on the topic in Victorian Periodicals Review.

[3] See Lee Erickson’s The Economy of Literary Form (106-14) for a full discussion of Thomas Carlyle’s ironic response to the industrialization of publishing and especially the dominance of periodical literature.

[4] Its status as a date-stamped commodity has been identified as a critical characteristic of the periodical by critics from James Mill to Margaret Beetham (21).