Pamela K. Gilbert, “On Cholera in Nineteenth-Century England”

This essay will focus on how the British understood and responded to the cholera epidemics that swept Britain four times from the early eighteen-thirties to the mid-eighteen-sixties, with special attention to the first epidemic and how it related to political Reform.

Virginia Zimmerman, “On Accidental Archaeology”

Archaeological excavations in the nineteenth century presented images of past and present collapsed together. Examining the accidental excavation of Roman remains in London and the failed excavation of Silbury Hill in Wiltshire, this essay shows how the intrusion of material from one time into another disrupted notions of linear chronology.

Joseph Viscomi, “Blake’s Invention of Illuminated Printing, 1788”

William Blake invented a printing technique known as relief etching and used it to print most of his poetry. He called the technique illuminated printing and the poetry illuminated books. Nearly all of his critics believe that the idea for illuminated books preceded the invention of relief etching, that either the idea of text integrated with images on the same page or Songs of Innocence actually mocked up on paper was the mother of invention. This essay, however, approaching the question of the technique’s origin from the context of other new print technologies of the day, argues that illuminated poetry was the child and not the mother of invention. There were no “illustrated songs” on hand or even in mind needing a technique by which they could be printed in facsimile. Blake’s idea of publishing himself occurs only after the invention of relief etching, once he sees that he could use his new mode for writing as well as images and both in the same space.

Gillen D’Arcy Wood, “1816, The Year without a Summer”

The so-called “Year Without a Summer”—1816—belongs to a three-year period of severe climate deterioration of global scope caused by the eruption of Mt. Tambora in Indonesia in April, 1815. With plummeting temperatures, and disruption to major weather systems, human communities across the globe faced crop failures, epidemic disease, and civil unrest on a catastrophic scale. In cultural terms, the dreary summer of 1816 is best known as the setting for Mary Shelley’s writing of Frankenstein, a novel whose iconic Creature offers a figure for the millions of hungry and dispossessed of Europe during the protracted climate emergency that followed Tambora’s eruption.

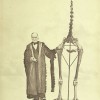

Gowan Dawson, “On Richard Owen’s Discovery, in 1839, of the Extinct New Zealand Moa from Just a Single Bone”

In 1839 Richard Owen inferred the existence of a hitherto unknown giant flightless bird in New Zealand from the evidence of just a small fragment of femur bone. This prediction was spectacularly confirmed three years later with the arrival of a consignment of bones from which Owen was able to reconstruct the entire skeleton of the wingless Moa or, as he named it, Dinornis. This essay explores the scientific and religious implications of Owen’s famous feat of inductive reconstruction, and also examines how it was represented in the Victorian print media.

Martin Meisel, “On the Age of the Universe”

The Charles Darwin-inspired debate over the Age of the Earth that pitted contemporary Physics against the theory and practice of contemporary Geology was intimately tied to recent unsettling projections on the thermodynamic fate of the universe. The leading voices in the debate were William Thomson, later Lord Kelvin, and Thomas Henry Huxley, Darwin’s most able champion. The argument—resolved only in the next century—has exemplary value as an intractable dissonance between two vigorous and well established, but not entirely secure scientific disciplines. And its content laid some of the groundwork for the pessimism that qualified the cult of progress and the whiggish habits of cultural and material complacency towards the end of the century.

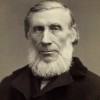

Bernard Lightman, “On Tyndall’s Belfast Address, 1874”

John Tyndall’s Belfast Address at the British Association for the Advancement of Science in 1874 touched off a heated controversy over his alleged materialism. His enemies expanded their criticism of his materialism to include Victorian scientific naturalists. An analysis of the Belfast Address and the controversy surrounding it provides insight into the status of Victorian scientific naturalism during the 1870s.

Garrett Stewart, “Curtain Up on Victorian Popular Cinema; Or, The Critical Theater of the Animatograph”

Hard on the heels of the Lumière “Cinématographe” in its Paris debut, the West End appearance of its most successful British equivalent, Robert W. Paul’s “Animatograph,” brought the apparatus for moving-image projection before a British public that would soon flock to its display of miscellaneous short films in theatrical venues all across England, propelling a widespread Victorian fascination with the new medium of visual spectacle and eventual (edited) storytelling, the latter in narrative formats by turns comic, melodramatic, and fantastic. In these emergent genre bearings alone, here was an entertainment technology that looked back into the earlier Victorian period as well as forward to both popular and experimental modernism. Much recent commentary has aimed at connecting this next-century destiny not just to the medium’s Victorian technological origins but to cultural orientations—and literary prototypes—in nineteenth-century habits of attention and imagination.