Abstract

In November 1859 and January 1860, two new shilling monthly magazines, Macmillan’s Magazine and Cornhill Magazine, entered Victorian markets. Long considered a landmark of Victorian literature and culture in twentieth-century publishing histories, this dual debut is both a historical event and a useful lens for reconsidering methods of print culture studies today.

The appearance of new monthly magazines in 1859-1860 is at once a landmark event in canonical literary and publishing history and, viewed from within alternative materialist histories of Victorian print culture, a minor ripple. Thus the inaugural issues of Macmillan’s and Cornhill Magazinesreflect on disciplinary practices and the history of scholarly commentary as well as on new reading opportunities, commodities, and literary production in mid-Victorian England.

Monthly magazines were situated between quarterlies, notable for extended reviews of current books, and weeklies, e.g., Charles Dickens’s Household Words. Both monthlies and weeklies included literary content, but weeklies often adopted newspaper formats and could capitalize on their greater currency, whereas monthlies featured longer contributions more suited to leisurely consumption (Law; Shattock, “Monthly”; Shattock, “Quarterly”). Entire dissertations (e.g., Schmidt) and special issues (Scheuerle) have been devoted to Cornhill Magazine, a recent book to Macmillan’s Magazine (Worth). Richard Altick ties the impact of these two magazines to the specific interests of an educated middle-class readership:

Between the London Journal’s uncultivated audience and the intellectual one of the Athenaeum there lay a growing public which, until the sixties, had been inadequately cared for, largely because of the rush to accommodate the semiliterate millions. This was the middle-class audience of superior education but relatively little spending money: the people who disdained cheap weeklies, with a few exceptions like Household Words, but who could not spare the two shillings or half-crown at which the principal monthly magazines were priced. To their rescue came the shilling monthly. Within three months of each other, in the winter of 1859-60, Macmillan’s Magazine and the Cornhill Magazine were launched. The first number of the latter sold an astounding total, considering its price, of 120,000 copies. (358-59)

If rising demand for serial fiction also played a role, the successful debut of the new shilling monthlies was principally an event in middle-class culture, the cultural zone from which so many of the literary works now considered canonical emerged.

Both Macmillan’s and Cornhill helped popularize and entrench the practice of reading quality fiction, poetry, and nonfiction prose serially and in juxtaposition with each other. Both magazines also had strong ties to book publishers—Macmillan’s to the eponymous press of its founder Alexander Macmillan and Cornhill to the firm of Smith, Elder, and Company—links that provided an incentive to editors for recruiting well-known or emergent talent that could then be redirected to book markets. As Altick notes, both sold for a shilling, well above the price of downmarket weeklies or cheap magazines, but less than half the price of Bentley’s Miscellany (which first serialized Oliver Twist, 1837-1839), Blackwood’s Magazine (in which Eliot’s Scenes of Clerical Life first appeared, 1857), Fraser’s Magazine (which serialized Carlyle’s Sartor Resartus, 1833-1834, and Thackeray’s Catherine, 1839-1840), or New Monthly Magazine (home to serials by Frances Trollope and Capt. Marryat in the late 1830s and 1840s).

There were significant differences between the two titles, however. Macmillan’s was unillustrated, generally printed in double columns, and hosted articles touching upon controversy; its opening article, by editor David Masson, addressed “Politics of the Present, Foreign and Domestic,” and ended by endorsing (not without more than a soupçon of self-interest) universal primary education so that the lower classes would receive the “greatest” franchise, “the franchise of books” ([Masson] 10). Macmillan’s also gave prominence to poetry relative to Cornhill and the later Fortnightly Review (Hughes, “What” 95), featuring the poet laureate and his brother, Charles Tennyson Turner, in its first year; and after February 1861, with the publication of “Up-hill,” Christina Rossetti became something of a house poet. Aimed at a more intellectual readership than Cornhill (Ellegård 19), Macmillan’s also had a smaller circulation, rarely over 20,000.

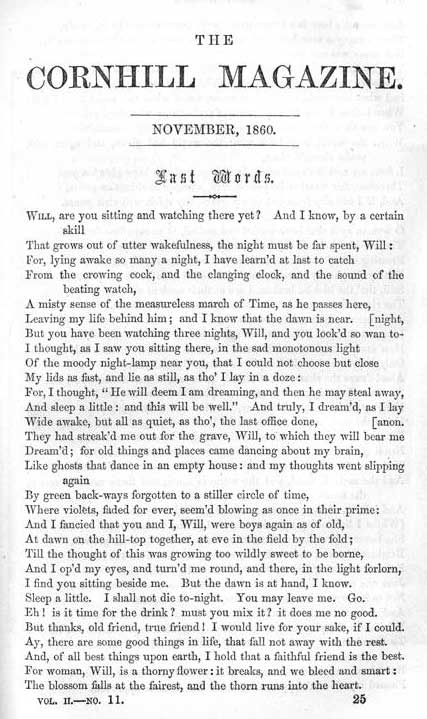

Cornhill Magazine tends to dominate discussion of the impact of new shilling monthlies in the 1860s, not illogically since it also dominated the market, at least during its first few years. Why was this so? In part, the journal had the attraction of a celebrity author, William Makepeace Thackeray. Of course, successful celebrity editorship had been pioneered by Charles Dickens a decade earlier, first with Household Words (1850-1859), then with All the Year Round (founded 1859). Cornhill was far more expensive than Dickens’s second weekly literary magazine, which was serializing Wilkie Collins’s Woman in White (1859-1860) when Cornhill debuted. But in contrast to the 24 unillustrated, closely-printed pages that readers got for twopence when they purchased All the Year Round, Cornhill offered 128 pages of content per issue, nearly six times the span of the Dickens title at precisely six times the cost. Moreover, Cornhill, unlike Dickens’s weekly, offered two illustrations and numerous vignette drawings, many by leading artists of the day (e.g., John Everett Millais and Frederic Leighton); two (not just one) concurrent serial novels by quality authors, beginning with Trollope’s Framley Parsonage and Thackeray’s Lovel the Widower (plus Thackeray’s Roundabout Papers); numerous substantial essays; a few poems (including Tennyson’s “Tithonus” and Elizabeth Barrett Browning’s “The Great God Pan” in 1860); and upmarket printing that resembled book layout. As Mark Turner points out, All the Year Round’s alternative sales format as a monthly (which bundled together all the weekly issues) also sold for a shilling but did not offer a similar array of features (Turner, “Telling” 120-21). Cornhill has also figured in literary histories because it marked Trollope’s emergence as a major Victorian serial novelist when Framley Parsonage, illustrated by Millais, became immensely popular (Turner, Trollope 5). Though Cornhill’s high sales figures slumped toward the late 1860s, this was in part because by then it had spawned so many imitators after it proved the marketability of a shilling monthly aimed at middle-class fiction readers (Turner, “Telling” 121). A final factor in Cornhill’s prominence within literary history is that, poets aside, so many major mid-Victorian authors appeared in its pages, from Gaskell and Eliot to Ruskin and Arnold.

Yet it is possible to overemphasize the newness of the shilling monthlies. As the references above to Blackwood’s and other magazines indicate, serialization of novels in magazines dated back to Bentley’s (and also Metropolitan Magazine) in the 1830s. Once a Week, the illustrated weekly spun off by the firm of Bradbury and Evans after Dickens broke with the firm over the announcement of his marital separation, rivaled Cornhill’s upmarket visual production in its lavish illustration by leading artists, much of it devoted to poems (Hughes, “Inventing” 41-42). Macmillan’s, on the other hand, deliberately echoed magazine formats from the past in the first issue’s concluding selection, a convivial, freewheeling “Colloquy of the Round Table.” If the title registered the impact of Tennyson’s Idylls of the King published the prior July, the colloquy harked back to the “Noctes Ambrosianae” of Blackwood’s, a series of 71 colloquies appearing from 1822-1835. The most famous “Noctes” personage, the Scots Ettrick Shepherd, was likewise echoed in the inclusion of a Scots Round Table “brother,” Andrew McTaggart. Yet the colloquy, designed to be a recurring feature, was out of step with the 1860s, and after two issues the “Round Table” was quietly dropped. The point remains that innovations represented by Macmillan’s and Cornhill were at best uneven, and their distinctiveness must be qualified.

With widespread digitization of Victorian periodicals, an entirely new context for viewing the new shilling monthlies has emerged. First, in contrast to the importance of Cornhill and Macmillan’s for studies of canonical literature and mid-Victorian middle-class readerships, two titles of limited circulation become minor presences when millions of periodical pages from hundreds of titles over the course of the nineteenth century can be searched in seconds. Second, the rise of cultural and popular culture studies suggests that we may learn more about a majority of Victorians by attending to those titles most commonly read—e.g., the London Journal with its “uncultivated audience,” in Altick’s words (estimated at 200,000 in 1860 in the online Waterloo Directory of English Newspapers and Periodicals [North]). Third, when the object of study is the mass medium of print culture as a whole, understanding a dynamic system of print exceeds the importance of a mere two titles at mid-century. The search techniques of digitized periodicals are also driving different methods from that of consecutive reading of a single or multiple issues of a famous periodical (especially since browsing is more comfortably undertaken in hard copy than online at present). Data-mining and keyword searches, the powerful tools of digitization, make it possible to ask new questions, especially about the recurrence of phrases (hence rhetoric) or crimes (hence cultural anxieties) across classes and multiple titles. Put another way, when the object of study becomes Victorian journalism and media (see, e.g., Brake, Subjugated and “Tacking”) rather than literary history and major authors, then Cornhill and Macmillan’s necessarily play bit-parts rather than major roles, or need to be investigated more for their editorial policies regarding signature and politics rather than their literary content.

That the two new shilling monthlies can prompt scholars, teachers, and students to ask what counts most in literary study attests to one use of attending to 1859-1860 and the new shilling magazines that emerged. Along with general study of Victorian serial fiction, they also remain very relevant to the classroom, since reading novels in parts (whether Tom Brown’s Schooldays, the inaugural serial of Macmillan’s, or Framley Parsonage, the inaugural serial of Cornhill) provides a means of enabling contemporary students to complete and enjoy long novels and to undertake original archival research by exploring the interactions between serial parts and other features surrounding them (Hughes and Lund, Victorian 275-78 and “What”; Mangum). Finally, studying Cornhill and Macmillan’s can, along with digitization and study of Victorian visual culture and journalism, underscore the point that all literary texts are mediated and remind the historically minded that the Victorian era, too, played a crucial role in media history.

HOW TO CITE THIS BRANCH ENTRY (MLA format)

published January 2012

Hughes, Linda K. “On New Monthly Magazines, 1859-60.” BRANCH: Britain, Representation and Nineteenth-Century History. Ed. Dino Franco Felluga. Extension of Romanticism and Victorianism on the Net. Web. [Here, add your last date of access to BRANCH].

WORKS CITED

Altick, Richard D. The English Common Reader: A Social History of the Mass Reading Public, 1800-1900. 1957. Fwd. Jonathan Rose. 2nd ed. Columbus: Ohio State UP, 1998. Print.

Brake, Laurel. Subjugated Knowledges: Journalism, Gender and Literature in the Nineteenth Century. New York: New York UP, 1994. Print.

—. “Tacking: Nineteenth-Century Print Culture and Its Readers.” Romanticism and Victorianism on the Net 55 (2009): n. pag. Web. 31 Oct. 2011.

Brake, Laurel and Marysa Demoor, eds. Dictionary of Nineteenth-Century Journalism. Ghent: Academia P; London: British Library, 2009. Print.

Ellegård, Alvar. “The Readership of the Periodical Press in Mid-Victorian Britain: II.” Victorian Periodicals Newsletter 13 (1971): 3-22. JSTOR. Web. 29 Oct. 2011.

Hughes, Linda K. “Inventing Poetry and Pictorialism in Once a Week: A Magazine of Visual Effects.” Victorian Poetry and the Book Arts. Ed. Lorraine Janzen Kooistra. Spec. issue of Victorian Poetry 48.1 (2010): 41-72. Print.

—. “What the Wellesley Index Left Out: Why Poetry Matters to Periodical Studies.” Victorian Periodicals Review 40.2 (2007): 91-125. Print.

Hughes, Linda K. and Michael C. Lund. The Victorian Serial. Charlottesville: UP of Virginia, 1991. Print.

—. “‘What Happens Next?’ From Historical Reading and Publishing to Classroom Practice.” Teaching Nineteenth Century Fiction. Ed. Andrew Maunder and Jennifer Phegley. Houndmills: Palgrave, 2010. 148-67. Print.

L[aw], G[raham]. “Weeklies.” Brake and Demoor 666-67.

Mangum, Teresa, ed. “Periodical Pedagogy.” Victorian Periodicals Review 38.4 (2006): 307-444. Print.

[Masson, David.] “Politics of the Present, Foreign and Domestic.” Macmillan’s Magazine 1.1 (November 1859): 1-10. Google Book Search. Web. 29 October 2011.

North, John S., ed. Waterloo Directory of English Newspapers and Periodicals: 1800-1900. Ser. 2. Web. 31 October 2011.

Scheuerle, William H., ed. “Cornhill Magazine II.” Victorian Periodicals Review 33.1 (2000): 1-103. Print.

Schmidt, R. D. Barbara Quinn. “The Cornhill Magazine: The Relationship of Editor, Publisher, Chief Novelist and Audience.” Dissertation Abstracts International, 41.7 (Jan. 1981) 3121A. MLA International Bibliography. Web. 29 October 2011.

S[hattock], J[oanne]. “Monthly Magazines.” Brake and Demoor 423.

—. “Quarterly Reviews.” Brake and Demoor 23.

Turner, Mark W. “‘Telling of my weekly doings’: The Material Culture of the Victorian Novel.” A Concise Companion to the Victorian Novel. Ed. Francis O’Gorman. Oxford: Blackwell, 2005. 113-33. Print.

—. Trollope and the Magazines: Gendered Issues in Mid-Victorian Britain. Houndmills: Macmillan, 2000. Print.

Worth, George. Macmillan’s Magazine, 1859-1907: ‘No flippancy or abuse allowed.’ Aldershot: Ashgate, 2003. Print.