Abstract

By 1888, the technology of the phonograph, and the medium of the phonograph cylinder, were established as market-ready. What was the imagined potential of this media technology in relation to known modes of communication and expression? This article recounts how “The Phonogram” or phonographic letter was prototyped from 1887 to 1892 through the efforts of Thomas Alva Edison and his London agent George Gouraud. Edison’s prototyping work and Gouraud’s efforts in developing recordings, scripts for phonogramic speeches, and formats for typographical transcription of the cylinder recordings represent a rich case study for documenting the nature and significance of their efforts to consolidate the medium and define the generic parameters of the phonogram (a speech recording) as a distinct form of global communication. By theorizing the relationship between late-Victorian concepts of medium, format and genre, respectively, and by interpreting the “first phonogramic poem” (16 June 1888) as an articulation of the meaning of sound recording at the historical moment that it arrived as a viable media technology, this article helps explain how sound recording technologies were imagined in relation to specific genres of communication. Drawing upon periodical literature, and documentation available through the Thomas Edison Papers archive—including phonogramic transcripts and speeches, marketing and foreign business strategies, patent applications, and packaging and design documents—this article explains, in particular, the generic and rhetorical protocols that informed the attempt to establish the phonogram as a new medium of intimate communication and international correspondence.

This article uses the historical instance of the first poem to be spoken into a phonograph and shipped across the Atlantic Ocean, from the ![]() United States to England, as a case study for considering how the media formats of early sound recording technologies were imagined in relation to particular generic forms of expression. From the moment of his first predictive pronouncements on the phonograph and its possible uses (in “The Phonograph and Its Future,” 1878), letter-writing was at the top of Thomas Edison’s list. During this early period of the tin foil phonograph, Edison describes his vision of a flat sheet of foil holding “in the neighborhood of 40,000 words” being “placed in a suitable form of envelope and sent through the ordinary channels to the correspondent for whom designed” (“Phonograph and Its Future” 531). In this early notional conception of phonographic correspondence, the limitations of the medium are identified not with the difficulties of technological development, but with the acceptance of the phonograph as the medium of language correspondence, globally. As Edison remarks, “In the early days of the phonograph, ere it has become universally adopted, a correspondent in Hong-Kong may possibly not be supplied with an apparatus, thus necessitating a written letter of the old-fashioned sort” (532). At the origin of the audio-recorded letter, or phonogram as it would soon be patented, is an imagined sense of the necessary relationship between a local and individualized media practice and the global (in Edison’s parlance, “foreign”) and universalized adoption of technology. Ten years later, Edison’s update on the state of the art of sound recording technology (“The Perfected Phonograph,” 1888) reports that, instead of foil sheets, “wax cylinders can be sent through the mail in little boxes which I have prepared for that purpose, and then put upon another phonograph at a distant point, to be listened to by a friend or business correspondent” (647). The problem of universalization has been considered and a public solution offered:

United States to England, as a case study for considering how the media formats of early sound recording technologies were imagined in relation to particular generic forms of expression. From the moment of his first predictive pronouncements on the phonograph and its possible uses (in “The Phonograph and Its Future,” 1878), letter-writing was at the top of Thomas Edison’s list. During this early period of the tin foil phonograph, Edison describes his vision of a flat sheet of foil holding “in the neighborhood of 40,000 words” being “placed in a suitable form of envelope and sent through the ordinary channels to the correspondent for whom designed” (“Phonograph and Its Future” 531). In this early notional conception of phonographic correspondence, the limitations of the medium are identified not with the difficulties of technological development, but with the acceptance of the phonograph as the medium of language correspondence, globally. As Edison remarks, “In the early days of the phonograph, ere it has become universally adopted, a correspondent in Hong-Kong may possibly not be supplied with an apparatus, thus necessitating a written letter of the old-fashioned sort” (532). At the origin of the audio-recorded letter, or phonogram as it would soon be patented, is an imagined sense of the necessary relationship between a local and individualized media practice and the global (in Edison’s parlance, “foreign”) and universalized adoption of technology. Ten years later, Edison’s update on the state of the art of sound recording technology (“The Perfected Phonograph,” 1888) reports that, instead of foil sheets, “wax cylinders can be sent through the mail in little boxes which I have prepared for that purpose, and then put upon another phonograph at a distant point, to be listened to by a friend or business correspondent” (647). The problem of universalization has been considered and a public solution offered:

To obviate the difficulty caused by the friend’s not having a phonograph of his own, pay stations will be established, to which any one may take the phonogram that he has received… Thus the phonograph will be at the service of every one who can command a few cents for the fee. And which of us would not rather pay something extra, in order to hear a dear friend’s or relative’s voice speaking to us from the other side of the earth? (647)

The phonogram provides a particularly useful cultural artifact for thinking about media concepts in relation to generic ones as they were conceived at this moment in history. More specifically, the phonogram raises, quite obviously at times, problems of media format that help elucidate how the discursive and literary activities developed around the phonogram were pursued as a cultural mechanism by which this new and partly imaginary media form might quickly be integrated into the habitus of daily life, across the globe. By 1888, the technology of the phonograph, and the medium of the phonograph cylinder, were more or less established as market-ready. The task for Edison was to realize this idea of the phonogram in material form. My task in this article is to unpack the role that an early recorded poem entitled “The Phonograph’s Salutation” played in this attempted process. Questions of format and genre dominate the story. To pursue the notion of a phonographic letter, a phonogram, Edison was compelled to imagine and embark upon an exercise in adapting the format of one medium, the phonographic wax cylinder, to the format of a much older medium, the handwritten or typed paper letter, sent by post in a flat envelope.

The idea of the phonogram at this stage posed a problem of compression. For reasons of compression—one might say, as if subject to an irrational desire for unattainable format compression—sending the improved (wax-coated) phonographic cylinders Edison had just invented through the mail was not the first resort in Edison’s phonogramic prototyping process but, rather, would be a later solution. If a phonogram was to be a spoken letter, then it would have to conform, in practice, to the constraints of the materials used for sending letters by mail. The reasons for this are most likely due to the fact that in 1887 the British Parcel Post service, while extremely well developed domestically, and robustly developed internationally, especially for countries in the Commonwealth, had not yet settled on rates with the United States, and thus would not be useful for sending parcel phonograms through an already established service (“Parcel Post Developments” 7).

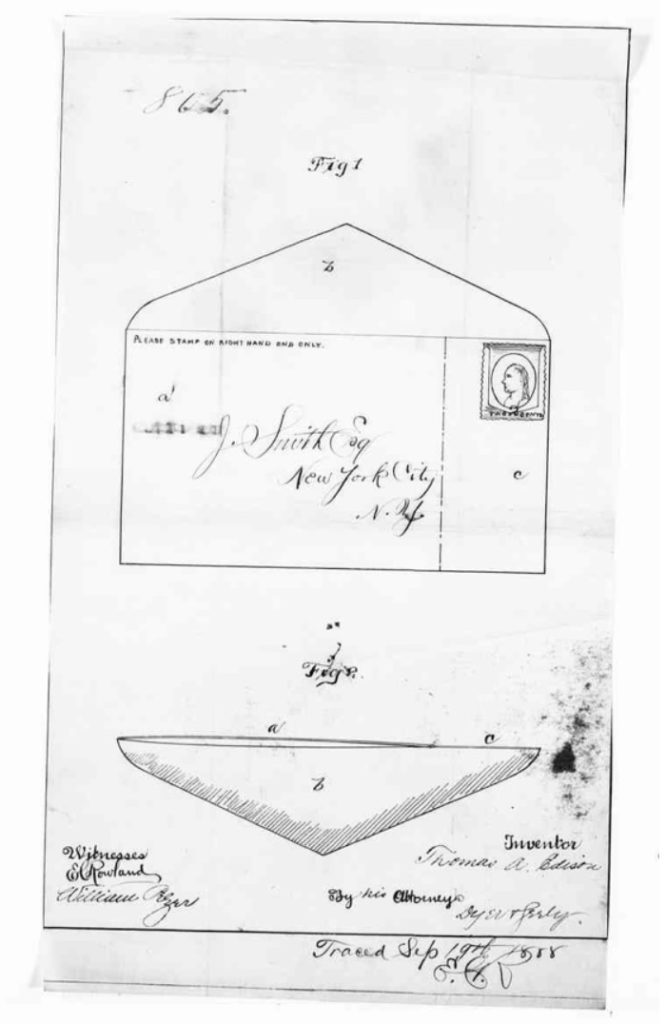

The shape and substance of the phonograph’s present media format was obstinate to the task at hand. Still, against the material realities of the wax phonograph cylinder as a three-dimensional cylindrical object, Edison pursued an idea of the phonogram as a flat material artifact. As Edison describes the artifact in his patent petition:

The object of my invention is to provide an envelope for enclosing flat phonograms, or collapsible phonogram cylinders such as are set forth in my application filed September 19th 1888, whereby such phonograms shall be securely enclosed and protected and the danger of injury to the record from the application of dating or cancelling stamps in the post office or of pressure in affixing the postage stamp shall be avoided. (“Patent Application” 29 September 1888)

The collapsible phonograph cylinder was itself a significant stretch, a truly notional improvement upon the recently improved media format of the wax cylinder. It is an example of a format that is strongly desired due to the constraints of the infrastructure already in place to support a completely different format (the paper letter).

Figure 1. Detail from “Patent Application, Thomas Alva Edison, September 29th, 1888.” Edison Papers Digital Edition. Web. 7 Nov. 2019.

In this phase of prototyping and petitioning, Edison (in part at the persistent prompting of his promotional agent, George Gouraud) is forced into imaging unlikely, skeuomorphic solutions to a formatting problem. The assertion of the “flat phonogram” or “collapsible phonogram cylinder” is a lovely conceptual gesture to consider in the process as it reveals just how seriously the inventor would allow formatting questions, and the postal rates that were connected with them, to inform his notional process of invention. In fact, the flat phonogram, as we know from Edison’s own writings and from newspaper reports, had already been imagined as soon as Edison introduced the tinfoil phonograph in 1877. That earlier medium, which entailed applying malleable foil to the phonograph cylinder for indentation by a stylus attached to a diaphragm, lent itself more easily to the idea of a flat format for recorded sound. The Times reported this idea of the phonogram in 1878, noting “that by its aid we have been promised communication with friends at a distance by sending a sheet of tinfoil—or phonogram, as we may with propriety term it—impressed with a message from our lips which they will reel off on their instruments” (The Times 4). But that was another version of the recording medium (one that did not sustain and reproduce sound well enough to prosper), and another time, and we were still a few years away from the material realization of truly functional, flat phonogramic media, even in 1888.

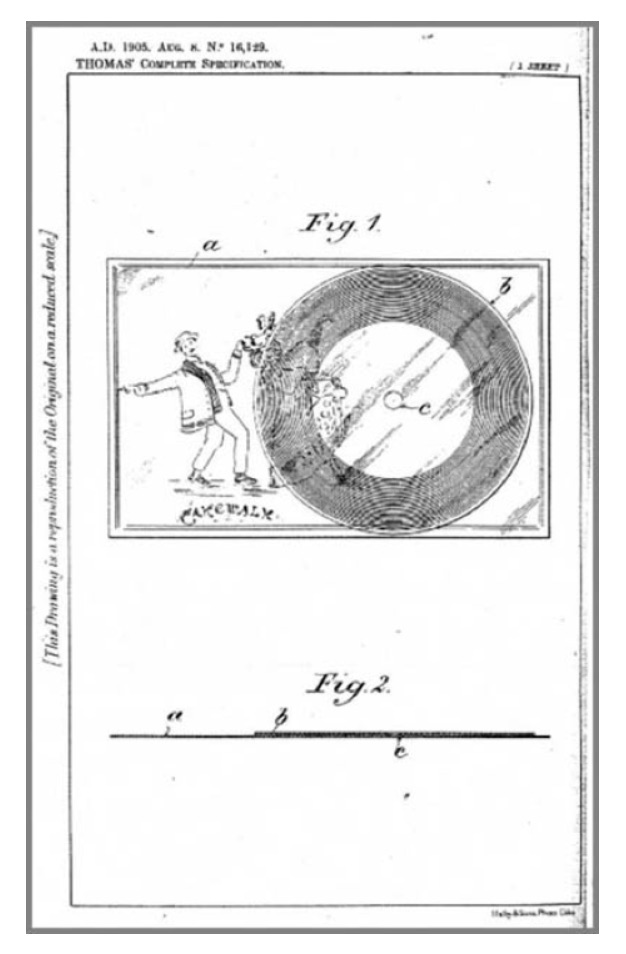

If I may digress into the near future for a moment before returning to my principal story about the first phonogramic poem: Edison’s original notion of a flattened phonogram correspondence was indeed realized in 1904 when Max Thomas, a Berlin-based phonograph machinery manufacturer successfully claimed a patent for phonogram cards (Lotz, “Exploratory History”).

Figure 2. Detail from Max Thomas, “Improvements in Phonogram Cards,” (Patent 16,129, 1905): 2. _lotz-verlag.de_. Web. 17 Feb. 2017.

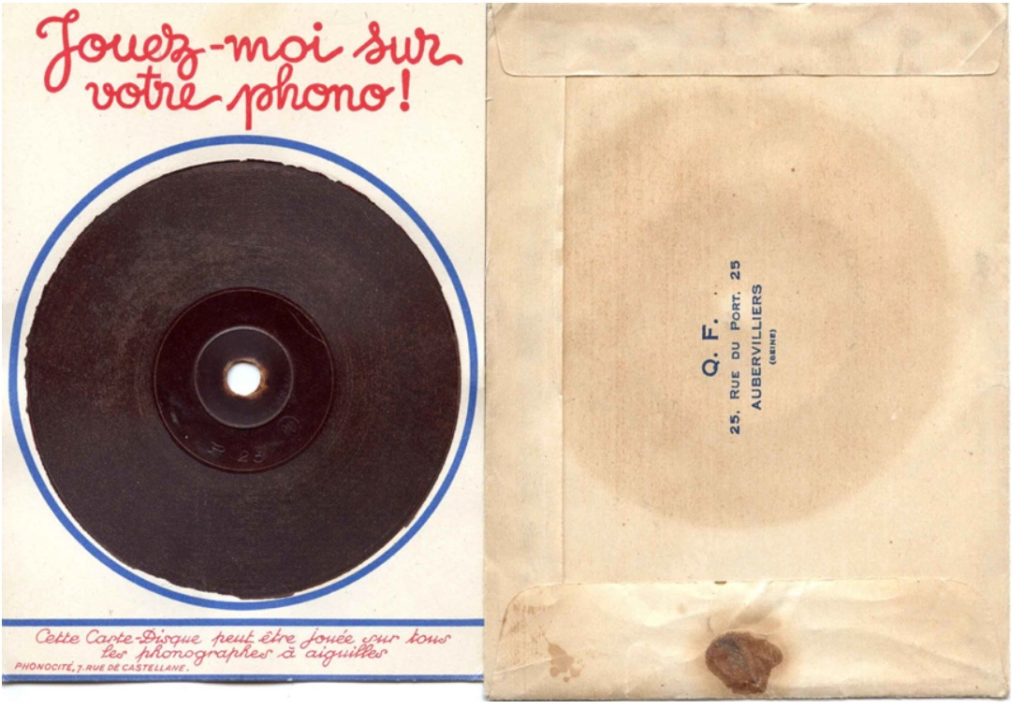

As Thomas notes in his Patent Claim: “For the purposes of my invention I prefer to employ disc records of thin transparent celluloid, first, because the small weight of this material does not cause any appreciable increase in the cost of postage, and second, because such records can be mounted over a picture or other representation without obscuring the same” (Thomas 1-2). Two specimens of Thomas’s version of the phonogram are noted by the General Post Office (GPO) in a letter concerning the conditions under which gramophone postcards are admissible in the British Postal Service. The letter, addressed to the International Bureau of the Berne Postal Union, ultimately concludes that these early examples of the phonogram card were deemed “not eligible for transmission as post-cards because of the presence of the adherent film, nor as printed matter because the character of individual correspondence had been imparted to them. They were therefore treated as letters” (“Letter on behalf of Postmaster General”). A year later a different kind of card was introduced in ![]() France. These were known as Cartes Postales Parlantes [Talking Postcards].

France. These were known as Cartes Postales Parlantes [Talking Postcards].

As the Chicago Tribune reported (9 September 1906):

The cards are about three times the thickness of an ordinary card, and are fitted with phonographic discs. Instead of writing your communication in the ordinary manner you make it verbally at the office where you purchase the card. It is recorded, the address is written on the other side, and it is then posted. The recipient places it in an ordinary phonographic machine and hears the voice of his or her friend. (“Talking Postcard New Fad” 1)

Figure 3. Image of _Carte Postale Parlante_, from Rainer E. Lotz, “Exploratory History of the Phono Postcard,” http://www.lotz-verlag.de/Online-Disco-Phonocards.html

What is most interesting about these material iterations of an idea is the puzzle they posed as classifiable objects for the International Postal Bureau. As the International Bureau of the Postal Union pressed the General Post Office for an answer on the postal rate to be applied to these new, thicker Cartes Postales Parlantes, should they soon appear in England (which was likely), the GPO deferred judgment on the matter until material specimens were provided. The International Bureau’s own recommendation entailed dividing the cards into three categories: blank, recorded but not yet played, and recorded and played (“simplement préparée pour recevoir l’impression phonographique”; “déjà gravée, mais pas encore exploitée”; “gravée et exploité… déjà rendu les sons phonographiques”). The first category should be stamped at 5 centimes (as it contained no actual message), and the other two categories should be stamped at 10 cents because they contain true correspondence readable by a phonographic device (“renferme de la vrai correspondence lisible par un appareil phonographique”). However, if the recording once played was no longer playable, it might be deemed (as it was in France) as having lost its “actualité” and “personalité,” and be treated (and rated) as no more than a business circular (Ruffy). The generic categorization of this media form of personal communication was determined as much by its content (or lack thereof) as by its material characteristics, although the relative flatness of the latter, which allied the talking postcard with silent written ones, was certainly important in allowing the analogical considerations of postal rates to happen in the first place.

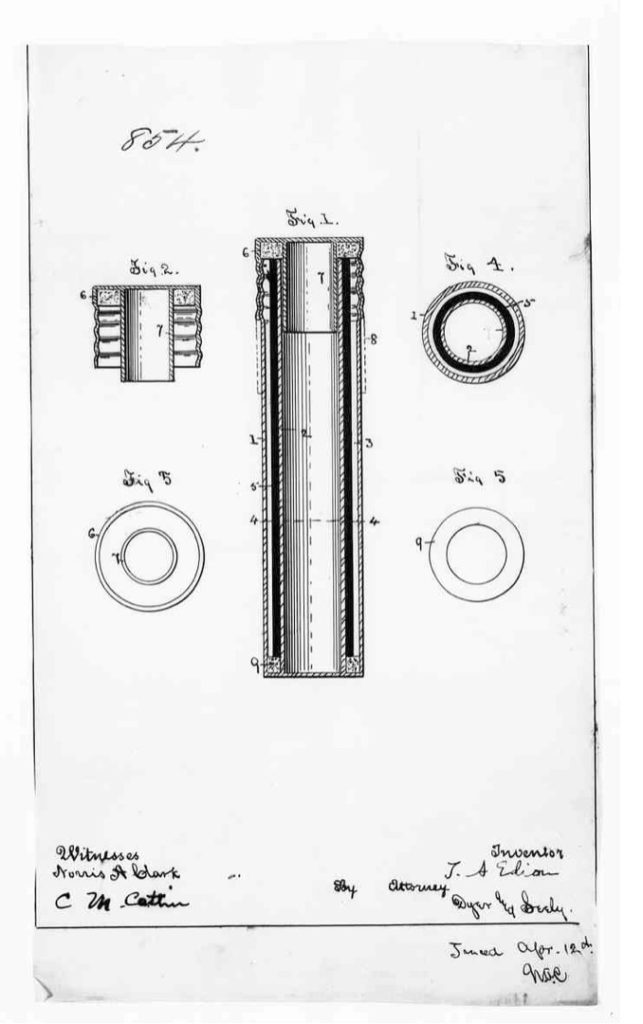

Edison’s own application for a flat phonogram envelope would be rejected five months after his first application in September 1888 due to the anticipation of this “invention” by L.P. Hayes in 1876 (Hall). An amendment to the design was submitted in March 1890 and rejected again a month later (Mitchell). After these two attempts, Edison abandoned this impractical line quite quickly and moved on to Plan B: sending phonograms as cylinders through the mail. The need to resort to parcel post over letter post represented a significant accommodation as far as format compression and shipping possibilities were concerned. The arguments over how to imagine the phonogram cylinder in relation to print communication required Edison and Gouraud to shift from analogy with the letter to analogy with the book, as Gouraud now attempted to secure the book rate for the phonographic cylinder as a parcel. However, Edison’s patent attempts for phonogram cylinder packaging were equally unsuccessful, and disruptive of the analogical formatting fiction they were engaged in perpetuating. The patents were rejected because the cylinder boxes resembled too much the package casings used for commercial merchandise that had nothing to do with intimate transatlantic communication. As far as the Patent Office was concerned, the phonogram might just as well be a fur hat or a jar of jam.[1]

Figure 4. Illustration from “Patent Application, Thomas Alva Edison, April 17th, 1890.” _Edison Papers Digital Edition_. Web. 7 Nov. 2019.

Edison’s own primary vision for the improved phonograph was only slightly less prosaic than the Patent Office’s assessment of his phonogram mailing cases. As Gouraud wrote to Edison in 1887, just as all this phonogram prototyping that I have described was beginning:

I know you attach more importance to the value of the machine for office work, dictation, &c., but I think the larger field is by the post, and a safe envelope is of especial importance; but even if you are right and I am wrong, the value of such correspondence as may be carried on socially across the seas will, as an advertisement, be incalculable,—far more impressive upon the imagination than the mere ability to dictate a letter to the machine and have it written off by someone in the same room. (“Letter from George Edward Gouraud to Thomas Alva Edison”)

From Gouraud’s perspective, the most captivating genre of the phonogram as a medium was to be international correspondence of a personal nature, not the office memo, because the imagined reach of the phonogram was global, and the idea of a personal message spoken across great distance was “far more impressive upon the imagination.” The problem of defining the form for and securing the safety of the phonogram as it travelled by post persisted as a concern during this early period of envisaging the phonogram as an opportunity for transatlantic marketing and exchange. For example, as the American newspapers awaited the arrival of the voice of Gladstone from England in the summer of 1888, they reported that some recordings sent by steamship had been “detained at the Post Office” and others that “had been opened by the Post Office authorities” were found to have been “badly damaged” somewhere en route (“No Phonograph from Gladstone”). The New York Times concluded that Edison “is at present directing his energies” to “perfecting a device that could withstand the hardships of an ocean voyage and such hardships as it might receive upon its travel” (“No Phonograph from Gladstone”). As this last report unwittingly suggests, the material format of the phonogram would determine its survival as a plausible medium and would arbitrate what genres might associate with it and define it.

Even as Edison was conceptualizing and applying for patents to secure exactly what a phonogram at this historical moment might be in material fact, Gouraud was busy inventing fictions of his own about the uses of Edison’s invention for international correspondence and lasting communication. As Gouraud wrote to Edison in 1887, when all this phonogram prototyping I have described was beginning: “The report of the Evening Post interview is being widely circulated in this country, and nearly everybody I meet asks me if it is true” (“Letter from George Edward Gouraud to Thomas Alva Edison). For the next five years, Gouraud would develop a series of promotional materials and activities to forward his vision of the phonogram as a format of global correspondence. Even his discussions of the packaging experiments that I have just described were framed in terms of exotic, international travel. As he explained in a lengthy (supposedly phonographic) interview with the Pall Mall Gazette a few months later:

You must understand that with regard to ‘mailing phonograms’ we are still experimenting with a view to determining as to the best form and material in which to make them for use by the public. We are keeping a careful record of materials, and the rout, that is, the geographical route, taken by each in reaching Mr. Edison. I am sending them to him by various routes round the world, so that they shall pass through all the climates and conditions of handling. To-morrow’s mail carries out those phonograms addressed, as you see, to New Zealand, to Australia, India, China, Japan, and South America. Those passing through the Red Sea and across the Equator will be so marked. They are addressed to my friends at different points, who will forward them to Mr. Edison. He will then see whether the record is perfectly intelligible, thus demonstrating whether the material of which the phonogram is made stands the various vicissitudes of travel and climate. (“First Interview Recorded by the Phonograph”)

Like an artifactual character in an eighteenth-century It-narrative—that is, a novel-length story told from the perspective of an object like a coin, book, or bible, and its adventures in circulation—we can almost imagine the phonogram returning from its journey in exotic countries and then reporting back to Edison upon its experience of the exposure, “I felt a little melty at the equator, but floated with ease in the Red Sea.”

The special intimacy of this new global medium as Gouraud was pitching it was imagined and defined in detail by Gouraud as he scripted the drama of their first transatlantic phonogramic exchange. The cylinder would be presented to a list of “distinguished” guests, invited “To meet Prof. Edison/ Non presentem, sed alloquentem!” (“Not present but in the voice”) in Gouraud’s London home, “Little Menlo.” Among the suggestions Gouraud made to Edison for the first phonogram were the use of the phrase from William Wordsworth “Shall I call the bird, or but a wandering voice” that had been registered as a kind of slogan to associate with the phonograph, and, significantly, the use of very specific protocols of address as far as spatial location was concerned (Andrews xv).

In these directives, and in the organized scenes of their presentation, the predominant generic forms that the phonogram as a mode of communication could best accommodate were imagined and developed, and to some extent, conflated with the media format of the phonogram, itself. What, we might ask, was the phonogram as a genre or form of communication in 1888? The genre was defined by its combination of geographical specificity and universality, intimacy, and publicity. It is, thus, not surprising that the two dominant genres of the earliest phonograms actually recorded consisted of either poetry or personal testimonials spoken to Edison from admiring celebrities. The poem and the testimonial represented generic forms that functioned simultaneously as private and public utterances, the poem as a private effusion serving as a public means of experiencing collective sentiment, and the testimonial as a personal, intimate comment of praise that may also serve as public advertisement.

The list of recordings Gouraud collected as phonograms to be sent back to Edison over the next four years included commissioned recordings by former British Prime Minister William Ewart Gladstone[2] and Florence Nightingale as well as testimonials and toasts mostly recorded at Gouraud’s “Little Menlo” home in Norwood, spoken by Cardinal Manning, Arthur Sullivan, Robert Browning, P.T. Barnum, Isaac Pitman, Henry Cecil Raikes (the Postmaster General himself), and many others. I will not dwell on these “at home recordings” as they have been usefully discussed by others (Maxwell; Picker 110-120). Instead, I will close this discussion of the mediated format of the phonogram circa 1888 with a closer look at the preparation and framing of what was dubbed “The First Phonogramic Poem” composed and recorded by the poet, Rev. Horatio Nelson Powers, a moderately well-known preacher and writer, who also happened to be George Gouraud’s brother-in-law.

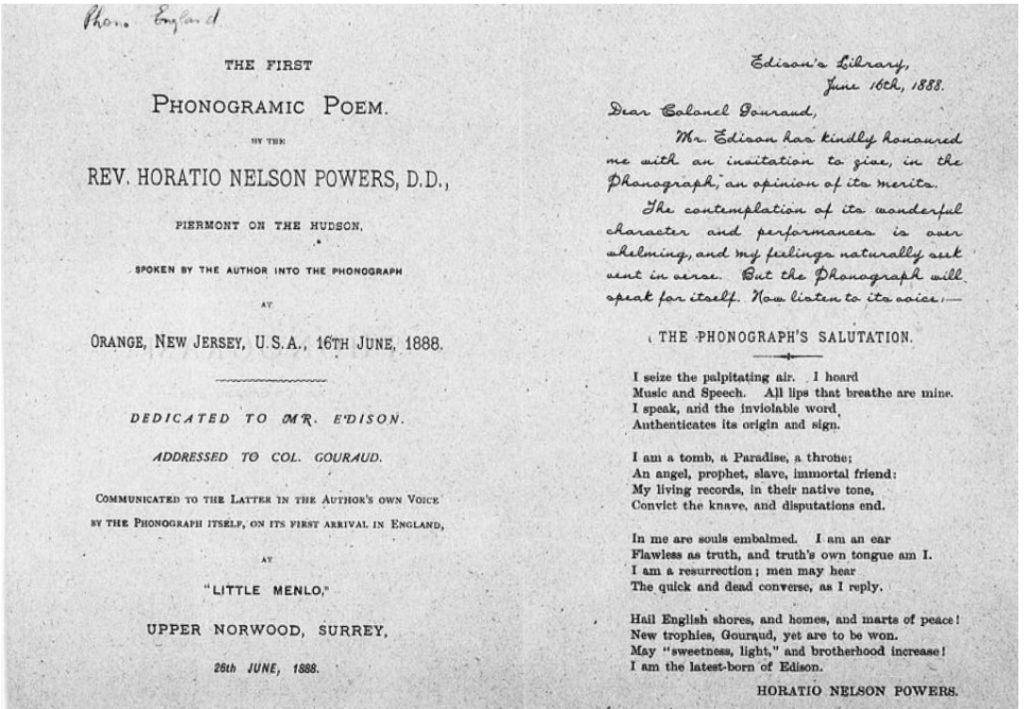

Powers first wrote to Edison on 5 January 1888 in a handwritten letter marked “Private” to notify the inventor of Gouraud’s plan to have Powers compose and then record a testimonial poem for use on the occasion of the first official phonogramic exchange display in England. Powers recorded his poem “The Phonograph’s Salutation,” spoken from the perspective of the phonograph, on 16 June 1888. Powers’s cylinder recording was sent to Gouraud from ![]() New York to England, along with a flamboyant prefatory note to Gouraud, which explains that, “[t]he contemplation of [the phonograph’s] wonderful character and performances is overwhelming, and my feelings naturally seek vent in verse” (Powers). If we examine for a moment the text that was printed to frame and commemorate the historical significance of Horatio Nelson Powers’s cylinder recording of “The Phonograph’s Salutation” we find a transcript not just of the poem, but also of the various directives (the whats, wheres, whens, hows, and to whoms) surrounding the transmission of the recitation of the poem; directives that ultimately suggest the conflation of author with phonograph; or the assertion of a phonographic character that gains its identity, its agency, its status as subject in a sentence, precisely by its ability to stand in and communicate for the author in its own voice (ambiguity intended).

New York to England, along with a flamboyant prefatory note to Gouraud, which explains that, “[t]he contemplation of [the phonograph’s] wonderful character and performances is overwhelming, and my feelings naturally seek vent in verse” (Powers). If we examine for a moment the text that was printed to frame and commemorate the historical significance of Horatio Nelson Powers’s cylinder recording of “The Phonograph’s Salutation” we find a transcript not just of the poem, but also of the various directives (the whats, wheres, whens, hows, and to whoms) surrounding the transmission of the recitation of the poem; directives that ultimately suggest the conflation of author with phonograph; or the assertion of a phonographic character that gains its identity, its agency, its status as subject in a sentence, precisely by its ability to stand in and communicate for the author in its own voice (ambiguity intended).

The textual framing for the recording is greatly overdetermined. The accompanying paper slip provides much of the basic metadata we would want for this recording and much more.[3] In particular, the slip articulates a complexly imagined circuit of movement from production to communication. An examination of the directives establishes precisely what we are dealing with (Figure 5).

Figure 5: Horatio Nelson Powers. “Phonogram from Horatio Nelson Powers to George Edward Gouraud, Thomas Alva Edison, June 16th, 1888.” _Edison Papers Digital Edition_. 7 Nov. 2019.

We have before us “The First Phonogramic Poem”—dubbed so, according to newspaper reports, “by virtue of that fact that it has never yet been in manuscript” (“Mr. Edison’s Phonograph”). The poem is composed by The Reverend Horatio Nelson Powers of Piermont on the Hudson. Spoken by the author (Powers) into The Phonograph at “Orange New Jersey” on June 16th, 1888. It is Dedicated to Mr. Edison, Addressed to Colonel Gouraud, and Communicated to the latter (Gouraud) “in the Author’s own voice by the Phonograph itself, on its first arrival in England, at ‘Little Menlo.’ Upper Norwood, Surrey, 26th June, 1888.” (That’s the address of Gouraud’s home.) It is this last sentence that most interests me, especially the paired phrases “in the Author’s own voice” and “by the phonograph itself,” which, together, grant the agency of vocal delivery to each of our heroes (Powers and The Phonograph) equally. This description of events is not quite accurate, or, at least its accuracy depends upon certain assumptions about the uniformity, the hegemony of the phonograph as a character, as a subject in a sentence. And such subjective hegemony equates, in business terms, in the mindset of Edison and Gouraud, with a customer’s faith in “universal standards” and upon the ultimate success of Edison’s brand of machine as the universally adopted technology. This first phonogram poem, apart from functioning as a possible means of promoting Gouraud’s son-in-law as a “well known and gifted” poet (as Gouraud describes him in a letter to the editor he had prepared for The Times, reporting on the “first phonogram event”), was asserting the status of Edison’s machine over others as the device of universal playback standards, the worldwide adoption of which would enable fulfillment of the idea of the phonograph as a new technology of global correspondence (Gouraud, “Mr. Edison’s Phonograph”).

The conflation of speaker (Powers) with medium (phonograph) is here enacted through a generic conceit of the universalized, individual voice of the phonogram (format) poet (author). It is a well-known conceit that Virginia Jackson and Yopie Prins have identified with the historical process of “lyricization” that informed the meaning of poetry from the late eighteenth century to the twentieth, by which the poem came to be understood as lyric through the conceptual universalization of the individual voice or speaker of a poem (Jackson and Prins). This process demands that we contextualize the generic conceit with historical and media specificity (Prins 44). In the case of the first phonogramic poem, this conceit makes the technology of the phonograph uniquely local and global: once adopted in each individual home it can be everywhere at once. The conceit complicates the question of “performance” since the focus in the scenario they are sketching identifies the true performance of the poem not with the moment of Powers’s reading into the recording device, but with the moment when the phonograph recites its existential monologue to an audience in London. As Jason Camlot has argued, Powers’s recitation seems to highlight an elocutionary performance that suggests an elevated, even “pure” vocal delivery (Camlot 42-43). (Further comments on the text and audiotext of the poem can be found in the COVE edition of “The Phonograph’s Salutation” designed to accompany this article.) The aspect of that audiotextual reading that I am stressing here focuses on the simultaneity in the phonogram as mediated speech genre, of the individual accents and inflections of Powers’s reading voice within the generic casing of the unaccented, universal voice of the phonograph. In short, the phonogram poem as a genre within this historical context of production and transmission is enacting its own form of compression, namely, that of compressing the universal and the particular into one expressive voice.[4]

Despite Edison and Gouraud’s attempt to invent the format and genre of the phonogram from 1888 into the early 1890s, and despite the brief appearance of phonogram cards in the first decade of the twentieth century, the word phonogram would soon come to have a different meaning associated with another, and at this point, still local medium in Britain. In 1911 the Joint Managing Directors of the Gramophone Company wrote to the secretary of the GPO, having heard that “the Post Office has adopted the word ‘Phonogram’ as a name for telephone-telegrams” (Clark and Dixon). Stating their feeling that this term had been well established in Britain and the Continent “as a generic word for any form of record of sound waves” the Gramophone Company protested, “It would be a great pity that the word should now be employed in a totally different signification”. The Postmaster General “carefully considered” the Gramophone Company’s “objection to the use of the word ‘Phonogram’ to denote a telephone-telegram” but finally did not think that there was any “sufficient ground for abandoning its use” in the new sense. And so, the file was closed on the phonogram and its transcriptive formats as a Victorian medium of global correspondence. The telephonic delivery of telegrams (the implementation of phonograms in this new sense of the word) grew steadily as a commonly used domestic practice in Britain from its experimental phase in the first decade of the twentieth century, well into the 1930s. In identifying the phonogram with the telephonic delivery of telegrams, the Post Office was reinstating the human agent as intermediary within the process of phonogramic communication, in a sense reversing the fantasies of private intimacy across distance that the phonogramic cylinder, with only a machine between corresponding parties, had promised. This new kind of phonogram reintroduced the alphabet to spoken telecommunication with a vengeance, as extensive protocols for enunciation and analogical spelling were established to avoid transmission errors.

Within its original, media-historical context, the case of the first phonogramic poem reveals an interesting example of conflation between a literary genre and a media technology format. It reveals how a generic idea of poetry, and the phonogram as a format of personal correspondence over distance that was imagined as superior to its alphabetic predecessor, the paper letter, were united in a vision of media technology, as a new and unprecedentedly immediate form of expression and communication.

published February 2020

HOW TO CITE THIS BRANCH ENTRY (MLA format)

Camlot, Jason. “The First Phonogramic Poem: Conceptions of Genre and Media Format, Circa 1888.” BRANCH: Britain, Representation and Nineteenth-Century History. Ed. Dino Franco Felluga. Extension of Romanticism and Victorianism on the Net. Web. [Here, add your last date of access to BRANCH].

WORKS CITED

Andrews, Frank. Edison Phonograph: The British Connection. London: City of London Phonograph and Gramophone Society, 1987. Print.

Camlot, Jason. Phonopoetics: The Making of Early Literary Recordings. Stanford, CA: Stanford UP, 2019. Print.

Clark, Alfred and Sydney W. Dixon. “Letter to the Joint Managing Directors of The Gramophone Company Ltd. to The Secretary General, G.P.O. London.” (10 May 1911), BT Archives, GB 1814, POST 20/1980B, 1911.

Edison, Thomas Alva. “Patent Application, Thomas Alva Edison, September 29th, 1888.” Edison Papers Digital Edition. http://edison.rutgers.edu/digital/document/PT032ABH. Web. 26 Jan. 2020.

——— . “Patent Application, Thomas Alva Edison, April 17th, 1890.” Edison Papers Digital Edition. http://edison.rutgers.edu/digital/document/PT032ACC. Web. 26 Jan. 2020.

———. “The Perfected Phonograph.” The North American Review 146 (1888): 641-650. JSTOR. Web. 8 Nov. 2019.

———. “The Phonograph and Its Future.” The North American Review 126 (1878): 527-536. JSTOR. Web. 8 Nov. 2019.

“First Interview Recorded by the Phonograph, The.” Pall Mall Gazette 48 (24 July 1888): 2. British Library Newspapers. Web. 8 Nov. 2019.

Gelatt, Roland. The Fabulous Phonograph: From Tin Foil to High Fidelity. Philadelphia and New York: J.B. Lippincott Company, 1955. Print.

Gouraud, George. “Letter from George Edward Gouraud to Thomas Alva Edison,November 19th, 1887.” Edison Papers Digital Edition. http://edison.rutgers.edu/digital/document/D7805ZER. Web. 8 Nov. 2019.

———. “Mr. Edison’s Phonograph.” Letter to the Editor of The Times, reprinted in The Little Gleaner: A Monthly Magazine for the Young 10, new series (1888): 172. Print.

Hall, Benton J., Commissioner of Patents. “Rejection of application for Envelopes &c., March 20, 1889.” Edison Papers Digital Edition. http://edison.rutgers.edu/digital/document/PT032ABH. Web. 26 Jan. 2020.

Jackson, Virginia, and Yopie Prins. “Lyric Studies.” Victorian Literature and Culture 27 (1999): 521-530. Print.

“Letter on behalf of Postmaster General of the United Kingdom to The Director of the International Bureau of the Postal Union.” (Draft, 26 September 1906; Sent, 2 October 1906), The Royal Mail Archive, Freeling House, GB 813, POST 29/908C, 1906.

Lotz, Rainer. “Exploratory History of the Phono Postcard.” Phonocards & Phonopost History. lotz-verlag.de. Web. 25 Feb. 2017.

Maxwell, Bennett. “The Incunabula of Recorded Sound: A Guide to Early Edison Non Commercial Recordings.” (MS, 1990). Print.

Mitchell, C.E., Commissioner of Patents.“‘Envelopes’, April 30, 1890.” Edison Papers Digital Edition. http://edison.rutgers.edu/digital/document/PT032ABH. Web. 26 Jan. 2020.

“Mr. Edison’s Phonograph.” The Daily News (30 August 1888): 6. British Library Newspapers. Web. 31 Jan. 2020.

“No Phonograph from Gladstone.” New York Times (17 July 17 1888): 8. ProQuest News and Newspapers. Web. 31 Jan. 2020.

“Parcel Post Developments in 1887.” The Times (1 January 1888): 7. The Times Digital Archive. Web. 26 Jan. 2020.

Picker, John. Victorian Soundscapes. Oxford, UK: Oxford UP, 2003. Print.

Powers, Horatio Nelson. “Phonogram from Horatio Nelson Powers to George Edward Gouraud, Thomas Alva Edison, June 16th, 1888.” Edison Papers Digital Edition. http://edison.rutgers.edu/digital/document/D8850ABQ1. Web. 7 Nov. 2019.

Prins, Yopie. “Voice Inverse.” Victorian Poetry 42 (2004): 43-60. Print.

Ruffy, Eugène. “Directeur, Bureau International de L’Union Postale Universelle, Letter concerning ‘Cartes postales parlantes’” (6 August 1906), The Royal Mail Archive, Freeling House, GB 813, POST 29/908C, 1906.

“Talking Postcard New Fad: Invention of a Frenchman.” The Chicago Sunday Tribune (9 September 1906): 1. Newspapers.com. Web. 26 Jan. 2020.

Thomas, Max. “Improvements in Phonogram Cards.” (Patent 16,129, 1905): 1-2. lotz- verlag.de. Web. 17 Feb. 2017.

Times, The [London, England]. (19 August 1878): 4. The Times Digital Archive. Web. 26 Jan. 2020.

Welch, Walter L. and Leah B. Stenzel Burt. From Tinfoil to Stereo: The Acoustic Years of the Recording Industry, 1877-1929. Gainesville, FL: UP of Florida, 1995. Print.

ENDNOTES

[1] Edison forwarded his first proposal for cylinder mailing cases on 17th April 1890, and an amended one on 19th April 1890. Both were rejected. (Edison, “Patent Application, Thomas Alva Edison, April 17th, 1890”).

[2] The story of Edison and Gouraud’s pursuit of Gladstone’s voice is interesting as an example of their desire to realize Edison’s predictions for the global import of the medium, and of George Gouraud’s methods of marketing the new technology in England. For accounts of Gouraud’s efforts, see Gelatt, 100-101; Welch and Burt, 103-107; and Andrews, xii-xix, 14-15.

[3] For an analysis of the recorded performance of the poem by Powers in the context of Victorian elocutionary performances of “the voice of the phonograph,” see Camlot, 38-39, 41-44.

[4] Solutions to the compression of storage media and data are pervasive in the history of technology and, as I am suggesting in this reading, our motives towards compression can be discerned in a wide range of cultural activities, as well.