Abstract

This article examines British writing about the 1876-8 famine in southern and western India. In British newspapers and journals, the turn to thinking about famine in terms of the total population obscured the extreme variations in food access that worsened with rising economic inequality. When the British press in the late-1870s turned to human causes of famine, they either argued that India’s population overburdened India’s land, or suggested that more rail construction would prevent enough deaths sufficiently to mitigate British responsibility for famine conditions. The turn to population-based arguments helped either to perpetuate the belief that famine was a quasi-natural part of India or to parse the sudden increase in the frequency and severity famines in India under British rule.

In 1876-8, somewhere between six and eleven million people died in southern and western ![]() India of starvation and other famine-related conditions.[1] After the failed monsoon in the summer of 1876, grain prices skyrocketed in and around

India of starvation and other famine-related conditions.[1] After the failed monsoon in the summer of 1876, grain prices skyrocketed in and around ![]() the Deccan plateau. Peasant cultivators in the

the Deccan plateau. Peasant cultivators in the ![]() Deccan, who had already been deeply in debt before drought set in, sold cattle, farm tools, and sometimes land in order to procure food. The situation was even worse for the landless agricultural laborers who were thrown out of work when harvests didn’t materialize.[2] Drought spread in the summer of 1877, extending the crop failures across southern India into the northwestern provinces and

Deccan, who had already been deeply in debt before drought set in, sold cattle, farm tools, and sometimes land in order to procure food. The situation was even worse for the landless agricultural laborers who were thrown out of work when harvests didn’t materialize.[2] Drought spread in the summer of 1877, extending the crop failures across southern India into the northwestern provinces and ![]() Punjab. The effects of the first year of drought had made the consequences of the second still worse: small cultivators no longer had the tools or cattle to grow even a meager harvest with the scant rain that fell.[3] Grain prices rose again. Still more small cultivators found themselves unable either to grow or to purchase food. By the late summer months of 1877, millions of people, especially those from the lower castes, were dying.

Punjab. The effects of the first year of drought had made the consequences of the second still worse: small cultivators no longer had the tools or cattle to grow even a meager harvest with the scant rain that fell.[3] Grain prices rose again. Still more small cultivators found themselves unable either to grow or to purchase food. By the late summer months of 1877, millions of people, especially those from the lower castes, were dying.

British land policies that vastly exacerbated peasant indebtedness were chief culprits in turning two years of drought into famine. Much of the region’s agricultural production had, by the 1870s, been converted to cash crops; when prices for a crop dropped, many small cultivators lost their incomes. The crash in cotton prices had proven especially disastrous for Indian farmers. During the years of the American civil war, cotton production had expanded vastly in the Deccan. After the war ended, though, cotton prices fell dramatically as English textile manufacturers purchased less Deccan cotton, favoring the American cotton that had reentered the global market.[4] Nor was it easy to convert cotton fields into ones that might grow food. Without income, farmers could not procure the supplies that would have been needed for undertaking such a conversion.[5] This economic precarity exacted a substantial toll from the health of small cultivators who were living near subsistence levels even before the drought. In the years before the famine set in, as Leela Sami observes, “it is probable that the large numbers of petty tenants, sharecroppers and artisans lived on the brink of hunger” (2597). Already coping with chronic hunger, these tenants, sharecroppers, and artisans were especially vulnerable to additional enfeeblement and disease when food became still more inaccessible during the dry summer months of 1876.

At the root of much of rural indebtedness was the urgency of paying the hefty annual land revenue assessment, which came due even if fields were fallow or if crops failed. By 1875, the debt crisis in the poorer parts of the Deccan was so dire that cultivators in a number of areas—Pune and Ahmednagar districts most famously—rioted against local moneylenders after the latter refused to lend money to peasants who needed it to pay their land taxes.[6] Land in most of the famine districts was held under a raiyatwari system in which land revenue taxes were to be paid directly by the occupiers of the land (who might or might not be the same as people doing the physical work of cultivating the land). British surveyors were to conduct surveys every thirty years in order to assess land revenue rates. While, by the 1870s there was, according to H. Fukazawa, “no rule” that determined assessment rates across regions (185), they were so extortionate as to be unmanageable for many small raiyats. The raiyatwari system seemed to promise greater independence for peasant cultivators than the system of zamindari landlords that prevailed in those parts of British India under the Permanent Settlement. But having to be directly responsible for heavy land revenue taxes nonetheless caused substantial difficulties for many raiyats, especially because failure to pay the tax meant that raiyats could be evicted and forced to forfeit their land rights.[7] As a result, many cultivators turned to village moneylenders in order to make their land revenue payments. Most commonly, peasants would borrow from local moneylenders who would mortgage the debtor’s lands under terms that allowed the moneylender to retain control over the land and its produce without taking on the burdens of cultivating it.[8]

Nascent peasant movements in the region cited these patterns of indebtedness as among their key concerns. The anti-caste activist Jotirao Phule, for instance, identified how high-caste moneylenders, the British courts, and excessive tax assessments impoverished and imperiled low-caste shudra peasants. Written in 1883, Phule’s pamphlet, entitled Cultivator’s Whipcord, notes[9]:

Our cunning government, through its brahman employees, has carried out surveys every thirty years and have [sic] established levies and taxes as they willed, and the farmer, losing his courage, has not properly tilled his lands, and therefore millions of farmers have not been able to feed themselves or cover themselves. As the farmers weakened further because of this, they started dying by the thousands in epidemics. There was drought to add to the misery, and thousands of farmers died of starvation. (167)

Phule does not discount the effects of the drought, but his analysis does not accord it primacy over the burdensome land tax, nor the Brahmin moneylenders whose interests the British courts systemically preferred to those of the small cultivators. That said, when crops failed as a result of drought, many more people found themselves unable to pay their land taxes; indeed, indebtedness increased vastly in famine years.

This attention to long-term economic structures contrasts sharply with British administrative writing, which tended to respond to disasters such as the famine as, in Upamanyu Pablo Mukherjee’s words, “governance glitches” (43)—momentary problems that need not require the undoing or radical overhaul of economic and governmental relations (43). As Mukherjee notes, even those writers who were outraged by the longstanding economic relations that produced famine policy chose to focus on the most arrestingly current images of suffering as sources of famine iconography.[10] In consequence, English-language famine writing in the 1870s predominantly understands famines as exceptional, contained events. Although the debates over railway construction in particular did voice attentiveness (however self-interested and misplaced) to longer-term conditions of British rule, they did little to interrupt the view of famine as a periodic crisis. Across the political spectrum, this mode of representing famine persisted even though, as Amrita Rangasami maintains, “the sudden collapse into starvation” in which “the stigmata of starvation become visual” ought to be read as only the last step of a much longer interweaving of dire political economic conditions (1800). All too commonly, even those depictions of famine that highlight very real immediate suffering nonetheless present famine as a wholly exceptional state, generally ignoring or undercutting the continuities between famine and the poverty and privation in non-famine times.

In articulating the view that famine marks, in Rangasami’s phrase, a “sudden collapse” (1800), nineteenth-century writers regularly cited a temporality that Thomas Malthus had schematized in his 1798 Essay on Population. The Essay, widely cited and reprinted throughout the nineteenth century, famously predicted that famine was a certainty in the absence of “preventive checks” that would keep population growth low by what he believed to be less violent means (Malthus 28). To make his case for the gradual reduction of population by a reduction in the birth rate, Malthus relied on the specter of sudden, apocalyptic suffering in the form of famine, plague, and war. In doing so, the Essay left the question of why populations might die in sudden catastrophic events and not in gradual declines undertheorized.

While the political economy of the 1870s saw changes to Malthusian theories of population, land, and value, a brute Malthusianism nonetheless inheres in many British analyses of famine through the 1870s. Arguing that southern India’s population had reached the maximum threshold that the land could sustain,[11] Viceroy Lord Lytton applied Malthusian principles, in Srinivas Ambirajan’s words, “rigidly to the Indian economy” (7). Somewhat ironically (given, for instance, Malthus’s support for the protectionist Corn Laws), Lytton was able deploy these arguments in order to license a stern laissez-faire philosophy under which, even amid dire local food scarcity, the Government of India refused to intervene in the grain markets. In August of 1877, as it was apparent that the monsoon had failed for a second year in a row, Lytton reaffirmed his position on free trade as a basis for justifying his decision not to import grain:

Free and abundant private trade cannot co-exist with Government importation. Absolute non-interference with the operations of private commercial enterprise must be the foundation of our present famine policy. . . I am confident that more food, whether from abroad or elsewhere, will reach

Madras, if we leave private enterprise to itself, than if we paralyse it by Government competition. (112)

Lytton’s confidence in the self-regulation of the market led to the prioritizing of the means for encourage private trade—the building of railways, for instance, that would assist export, while providing returns for investors in Britain who backed the rail expansion projects. Relief policies, in turn, were deliberately designed to be horrific.[12] For those people who managed to meet onerous eligibility requirements, the proffered “relief” provided only a wildly inadequate amount of food in return for exceedingly heavy labor.[13] As critics of famine policy made clear, the famine caused genocidal atrocities in the form of skeletonized bodies, scenes of people dying in front of grain depots or en route to cholera-ridden relief camps, feats of hard labor in which corpse-like men and children constructed railroads and canals in exchange for an utterly insufficient modicum of grain. Millions of the people who had not already starved to death were so enfeebled that they died of malaria and cholera.[14]

In setting forth this policy, Lytton was drawing on beliefs about population and infrastructure that were widely held in Britain. When the British press in the late-1870s turned to human causes of famine, they either argued that India’s population overburdened India’s land, or suggested that more rail construction would prevent enough deaths sufficiently to mitigate British responsibility for famine conditions. The turn to population-based arguments helped either to perpetuate the belief that famine was a quasi-natural part of India or to parse the sudden increase in the frequency and severity famines in India under British rule. A number of late nineteenth-century critics make the point that British tax policy, for instance, was instrumental in causing the huge increase in famines after the East India Company and then the Raj assumed control of India. The economic historian Romesh Chunder Dutt, for instance, points out that the East India Company continued to exact a heavy land tax through the 1769-1773 famine that killed a large percentage of the population of ![]() Bengal (Economic 52–3).[15] To be sure, India had experienced famine conditions prior to the arrival of the British. It is nonetheless salient that, as Amartya Sen notes, eighteenth-century Bengal had seen no real famine prior to the arrival of the East India Company (“Imperial Illusions” 28) and that severe famines would become such a regular occurrence in nineteenth-century British India.

Bengal (Economic 52–3).[15] To be sure, India had experienced famine conditions prior to the arrival of the British. It is nonetheless salient that, as Amartya Sen notes, eighteenth-century Bengal had seen no real famine prior to the arrival of the East India Company (“Imperial Illusions” 28) and that severe famines would become such a regular occurrence in nineteenth-century British India.

Reading famine as a by-product of population or lack of railroads also helped to mask famine’s wildly uneven effects within India. As Ajit Ghose argues, famines are exceptional events not because they are the necessarily apocalyptic results of a catastrophic weather event, but rather because they shift economic relations towards increasing inequality with extreme rapidity. While it is true that droughts leading to crop scarcity did occur regionally (though not nationally) in the famines between 1860 and 1910, focusing on drought and the availability of food in a given region thus misses crucial changes to social relations that render famine periods distinct from non-famine times. Drawing on and adapting Amartya Sen’s now famous argument that famine occurs as a result of a failure “exchange entitlements,” Ghose maintains that in the last third of the nineteenth century India saw “sudden changes in the distribution of food (and, relatedly, income)” (370) that highlighted and worsened poverty and inequality (384). Landless people starved, Ghose points out, because crop failure meant that they had been thrown out of work; others, however, prospered greatly during famine years.

In British newspapers and journals, the turn to thinking about famine in terms of the total population obscured the extreme variations in food access that worsened with rising economic inequality. These famine writings in turn had an effect on famine relief policy. British famine journalism during the late-1870s illustrates how ideas about population and infrastructure could simultaneously shape a famine policy that was renowned for its brutality and elicit the sympathy of British readers, many of whom donated money to famine relief funds as they encountered the news of what was happening overseas. In Britain, the celebrity of Malthus’s argument had occasioned the increasing cultural prevalence of population statistics, both through the expanding census apparatus, and elsewhere. In spite of the prevalence of Malthusian thinking, though, 1870s writing on famine and population rescripts the plot that Malthus had famously laid out eighty years earlier in a number of key ways. Famine writing showed a keen interest not only in the Malthusian theory of a relationship between population and land productivity, but also in the infrastructures that made this productivity possible. The debates over rail and irrigation that emerged in famine discourse were thus integral to the arguments that were circulating about the effects of population.

The Argument that Overpopulation Causes Famine

If, in Malthus, famine occurs when the population becomes too burdensome for agricultural resources on a given bit of land, by the 1870s the rhetoric on famine was newly attentive to the movement and settlement of people in response to local economy. In the development of classical economic liberalism through the middle years of the century, writing on famine loses some of the localism for which Malthus had been criticized. David Ricardo’s Principles of Political Economy had popularized the idea that more fertile tracts of land were more thickly populated first because the best land tended to be cultivated first, with worse land only coming into cultivation as better or better accessible land becomes overburdened.[16] Nor could a purely Malthusian theory of place and population hold sway in the new neoclassical marginalism developed in the 1870s by William Stanley Jevons and Alfred Marshall. When he set the examination questions for ![]() Cambridge’s 1874 Moral Sciences Tripos, Jevons asked students to assess the ethics, economics, and politics of British policy in famine-stricken Bengal, reminding students to “take into account the assertion of some eminent authorities that the population of the famine districts is becoming excessive, and that a recurrence of such famines appears to be inevitable” (132). Like Malthus, Jevons argues that supposedly excessive population must necessarily produce periodic famine. That said, Jevons’s economics were not fundamentally Malthusian; while Malthus concerned himself with production, Jevons focused nearly exclusively on demand or supply. His famous development of a theory of marginal utility cast utility as a measure of the scarcity of a commodity, but he remained uninterested in the scene of production relative to that scarcity.[17] This comparative lack of attention to production entailed a necessary shift in emphasis away from the more strictly Malthusian concern with the carrying capacity of a piece of land. Nevertheless, by the end of the 1870s, these assessments found well-publicized antagonists. First, some writers made the point that England did not produce its own food and therefore that it might be preposterous to assess the famine as a result of India’s inability to do so.[18]

Cambridge’s 1874 Moral Sciences Tripos, Jevons asked students to assess the ethics, economics, and politics of British policy in famine-stricken Bengal, reminding students to “take into account the assertion of some eminent authorities that the population of the famine districts is becoming excessive, and that a recurrence of such famines appears to be inevitable” (132). Like Malthus, Jevons argues that supposedly excessive population must necessarily produce periodic famine. That said, Jevons’s economics were not fundamentally Malthusian; while Malthus concerned himself with production, Jevons focused nearly exclusively on demand or supply. His famous development of a theory of marginal utility cast utility as a measure of the scarcity of a commodity, but he remained uninterested in the scene of production relative to that scarcity.[17] This comparative lack of attention to production entailed a necessary shift in emphasis away from the more strictly Malthusian concern with the carrying capacity of a piece of land. Nevertheless, by the end of the 1870s, these assessments found well-publicized antagonists. First, some writers made the point that England did not produce its own food and therefore that it might be preposterous to assess the famine as a result of India’s inability to do so.[18]

The effectiveness of these population-based arguments is especially striking given the continued prevalence of a conviction that population density also acted as both a sign of national prosperity and capitalist “development.” These views enjoyed a stunning tenacity even in the face of equally widespread concerns over the ills of crowded cities and slums. At the level of the country and the city, that is, population density marked an accomplishment; in some British writing about colonization, the city was both the result of a “civilized” drive to capital accumulation and the condition under which this drive could best develop. “Uncivilized” dispositions, that is, could be both the cause and the effect of sparse urban development. Under the heading of “Population Density”, the 1871 Census of England and ![]() Wales maintained that:

Wales maintained that:

when many families, with many wants, are brought into communication with each other, and produce a great variety of interchangeable articles for which there is a general demand, they suffer less from privation; for the number of persons living on the soil is no longer limited by the minimum amount of the crops in each homestead. Instead of one savage to a square mile there may be five houses, as there may have been in the later Saxon times . . . In the reign of Queen Victoria the houses on the same area are on an average seventy-three, occupied by eighty-seven families and three hundred and ninety people.” (Census of England and Wales for the Year 1871 General Report xxv)

While the tables that follow measure population density as persons to a square mile, the argument about communication, privation, and “interchangeable articles” suggests that what the census is interested in measuring is less the number of bodies occupying a tract of land and more the ease of exchange. Population density here indexes civilizational progress, assuming that greater exchange means less suffering. It can nonetheless be difficult to determine whether the Census wishes to see population density as a measure or a cause of the “communication” it prizes as a measure of civilizational development: being able to interchange articles means that more population density can occur, but this interchange also removes the limits to population density.

Nevertheless, these claims found their limit as, in particular, high population density was widely blamed for the 1873-4 famine in Bengal. During the Bengal famine, Lord George Hamilton, Under-Secretary of State for India, had observed that “the population of the district now affected by famine was probably the densest in the world

. . . very nearly double the density of the population of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and ![]() Ireland” (Hansard’s Paliamentary Debates 176).[19] In writing about famine, the debates over population in Bengal had to contend with the sharp contrast between the catastrophe and the somewhat better attenuated suffering of the Bengal famine only a few years earlier. According to British records, twenty-three people died from famine-related conditions in Bengal in 1873-4. However much we might mistrust these official numbers, they nonetheless contrast sharply with the famine later in 1876-8 in which millions of people lost their lives.[20] The lower death rate in the Bengal famine of 1874 had made it much harder to maintain that excessive population density caused millions of people to starve to death in the comparatively more sparsely populated areas around the Deccan plateau[21]

Ireland” (Hansard’s Paliamentary Debates 176).[19] In writing about famine, the debates over population in Bengal had to contend with the sharp contrast between the catastrophe and the somewhat better attenuated suffering of the Bengal famine only a few years earlier. According to British records, twenty-three people died from famine-related conditions in Bengal in 1873-4. However much we might mistrust these official numbers, they nonetheless contrast sharply with the famine later in 1876-8 in which millions of people lost their lives.[20] The lower death rate in the Bengal famine of 1874 had made it much harder to maintain that excessive population density caused millions of people to starve to death in the comparatively more sparsely populated areas around the Deccan plateau[21]

Nor were such blanket statements about population density merely descriptive political economic claims.[22] The proposition that excessive population density might lead to famine offered commentators in the British press a way of skirting the possibility that famine had resulted from appalling and cumulative effects of British rule. If anything, as The Economist opined in 1874, Britain should be concerned that it had encouraged Indians to be alive in the first place, not that it was letting people starve:

The effect of our rule in India has been to people the country now visited with famine much more densely than it was ever peopled before, much more densely than this country, or almost than any other part of the globe. . . .

Having created this vast precarious population, we feel, as Englishmen and as Christians, that we are bound to keep them alive. But this is incredibly difficult. . . . The native rulers formerly did nothing; one effect of these terrible visitations was that the numbers of the people were kept near to a manageable limit. But we have to deal with far greater numbers, and we have said that we will not permit any of them to perish. As by the unintended effect of civilized Government we have given life to an immense number of human beings, we cannot, in common humanity, according to our notions of humanity, leave them to perish. (“Neglected Aspects of the Indian Famine” 378–9)[23]

So keen is the author to deny that the restructuring of Indian economies that came with British rule—the drain of millions in revenue to Britain, the cultivation of export cash crops at the expense of grain, and the organization of the economy around the importation of goods from ![]() Manchester and other British industrial centers, for starters[24]—that British rule here appears almost sentimental and soft hearted, allowing the kind of undue prosperity that it should know necessarily leads to excessive population. The author, of course, forgets his famine history in multiple registers: famines were gruesome in India under both the East India Company and the Raj, and rulers before the British were not categorically and casually indifferent to human life in the way this article implies. What stands out in this mess of historical revisionism, though, is that population density appears to be a result of purported British benevolence and not of some characterological phenomenon supposedly unique to “lower Asiatics”: this writer finds it obvious that “civilized Government” has “given life” as though the birth-rate of Indian children was entirely determined by British decisions.

Manchester and other British industrial centers, for starters[24]—that British rule here appears almost sentimental and soft hearted, allowing the kind of undue prosperity that it should know necessarily leads to excessive population. The author, of course, forgets his famine history in multiple registers: famines were gruesome in India under both the East India Company and the Raj, and rulers before the British were not categorically and casually indifferent to human life in the way this article implies. What stands out in this mess of historical revisionism, though, is that population density appears to be a result of purported British benevolence and not of some characterological phenomenon supposedly unique to “lower Asiatics”: this writer finds it obvious that “civilized Government” has “given life” as though the birth-rate of Indian children was entirely determined by British decisions.

The comparisons of the two famines might have led to a renunciation of Malthusian thinking. Nonetheless, as these arguments circulated, muddled efforts appeared that sought to retain Malthusian principle in the face of evidence that seemed to contradict it. The Times’s correspondent in Madras offers a case in point in a dispatch that was reprinted in major English newspapers:

A great deal has been said about over-population in India and the Malthusian doctrine of the necessity of periodical famine and pestilence to remove the redundant people. The remarks on this head would be pertinent to the subject if the famine had displayed itself in the most thickly populated districts of the country, but, as a matter of fact the most thickly-populated districts have been able not onto to grow food enough for their own necessities, but to export to places where there was scarcity.[25]

Taking the export of grain as evidence that Bengal could sustain itself instantiates grave historical error on a number of fronts. Not only does it forget that Bengal could only weather the famine with imported grain from ![]() Burma (and thus did not produce its own necessities), it also makes a virtue of sending grain away from millions of starving people and leaves aside entirely the bitter irony that this much-needed food was shipped away through the railroads and canals that were built in the name of famine prevention. The clunky rhetorical turn of claiming that Malthus is not “pertinent” exists in order to avoid making the case that Malthus might be wrong. Instead of challenging the principles of Malthusian reasoning, the article suggests that the fact that Bengal suffered only a low death toll in 1874 is simply evidence that the dire Malthusian famine state had not yet been reached. In this way, in spite of its lip service to the irrelevance of Malthus, the dispatch sustains the belief that some relationship between population density and the fertility of the land determines the outcome of a famine.

Burma (and thus did not produce its own necessities), it also makes a virtue of sending grain away from millions of starving people and leaves aside entirely the bitter irony that this much-needed food was shipped away through the railroads and canals that were built in the name of famine prevention. The clunky rhetorical turn of claiming that Malthus is not “pertinent” exists in order to avoid making the case that Malthus might be wrong. Instead of challenging the principles of Malthusian reasoning, the article suggests that the fact that Bengal suffered only a low death toll in 1874 is simply evidence that the dire Malthusian famine state had not yet been reached. In this way, in spite of its lip service to the irrelevance of Malthus, the dispatch sustains the belief that some relationship between population density and the fertility of the land determines the outcome of a famine.

Nor did those who abandoned Malthusian tenets necessarily relinquish all conviction in an intimate relationship between population, land, and famine conditions. Hamilton himself offers a case in point, performing what seems to be an about-face on the Malthusian reasoning of his 1874 remarks. When he took up talking about Indian population density again in 1877, Hamilton’s articulation of the relationship between population density and land became much more Ricardian than Malthusian, doing away with the claim that famine results from the excessive burdening of the land by population. In a dinnertime speech, Hamilton chose to gloss population density not as a cause of or precursor to famine, as The Economist had suggested, but instead as quite the opposite.

It is in those parts of India where the annual rainfall is greatest and most regular that there is the greatest fertility and the most dense population. Or to put it in another way, the more dense the population of any locality is the less likely is that district to be visited by drought. (“Lord G. Hamilton, M.P., on the Indian Famine” 2)

Rather than a cause of draught or famine, that is, population density becomes an index of how improbable a drought or scarcity might be. While Hamilton insisted that both the Indian famines of the 1870s were “exceptional” in character, it is less than clear how his view of population sparseness as, in some sense, a predictor of “scarcity” was supposed to relate to his approval for a famine policy centered on work-based relief and on the notion that the English Treasury should invest only in remunerative infrastructure projects. On the evidence of his speech, one would conclude that India’s “independence and local financial responsibility” are in graver danger than the millions of human beings who died.

Proposed Infrastructural Remedies

These concerns over inculcating “local financial responsibility” nonetheless did not prevent the British from advocating British-backed railway expansion as the most appropriate means of redressing famine conditions. Thinking about missing infrastructure, that is, was not designed to challenge the effects of a laissez-faire political economy that sought to ensure grain revenues to European capitalists. Even most of those who preferred irrigation works typically skirted the economic arguments that would have challenged capital accumulation. The economist Srinivasa Ambirajan observes that while there “were practical difficulties, no doubt, the focus on the lack of transportation only hides the fact that “one cannot resist the conclusion that the officials as a class swore by the principles of non-interference in the grain market.”[26]

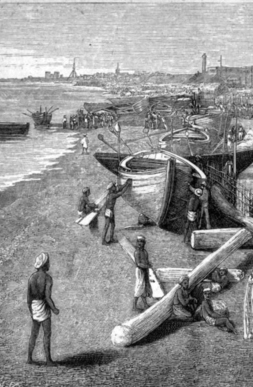

Most Britons in the late 1870s who took up the task of recommending infrastructural changes as a means of preventing famine cited the devastation of the 1866-7 ![]() Orissa famine in which, by some estimates, approximately a third of the population died. In most histories of nineteenth-century Orissa, the aftermath of the famine marks a shift through which the province’s economic circuits became less local. “The famine broke the isolation of Orissa,” the historian Ganeswar Nayak reports (346). Colonial officials, English-language journalists, and British political economists agreed that whatever famine relief the British administration undertook should focus on building better transportation networks. Following the Famine Commission’s advice, the colonial administration began building new canals, roads, and railways in Orissa beginning in 1867. After the famine, Orissa’s mud and dust roads—impassable in rainy seasons—were replaced with “modern” thoroughfares, ostensibly designed to prevent the recurrence of famine conditions.[27] Even Karl Marx concurred with other commentators in seeing missing “means of communication” as a culprit responsible for producing famine conditions. In London, at work on the manuscript of Capital I, Marx responded to the famine crisis by observing that:

Orissa famine in which, by some estimates, approximately a third of the population died. In most histories of nineteenth-century Orissa, the aftermath of the famine marks a shift through which the province’s economic circuits became less local. “The famine broke the isolation of Orissa,” the historian Ganeswar Nayak reports (346). Colonial officials, English-language journalists, and British political economists agreed that whatever famine relief the British administration undertook should focus on building better transportation networks. Following the Famine Commission’s advice, the colonial administration began building new canals, roads, and railways in Orissa beginning in 1867. After the famine, Orissa’s mud and dust roads—impassable in rainy seasons—were replaced with “modern” thoroughfares, ostensibly designed to prevent the recurrence of famine conditions.[27] Even Karl Marx concurred with other commentators in seeing missing “means of communication” as a culprit responsible for producing famine conditions. In London, at work on the manuscript of Capital I, Marx responded to the famine crisis by observing that:

In consequence of the great demand for cotton after 1861, the production of cotton, in some thickly populated districts of India, was extended at the expense of rice cultivation. In consequence there arose local famines, the defective means of communication not permitting the failure of rice in one district to be compensated by importation from another. (333)

Although this brief moment of attention to communication would prove important to Marx’s development of a theory of population, in the material that would become Capital II, Marx’s interest in the analytic of “communication” disappears in the later volumes of Capital. Instead, Marx shifts his analysis of the Orissa famine to emphasize the “unexampled export” of rice from Orissa to ![]() Australia, Madagascar and elsewhere.[28] Already by the end of the 1870s, the argument that remedying “defective means of communication” would prevent famine no longer seemed entirely viable. In the middle of the great famine of 1876-8 British commentators did not, as a rule, identify a shortage of roads, canals, or railroads as to blame for famine conditions, even though they continued to maintain that investing especially in rail would alleviate famine conditions in a partial and gradual way. The Orissa famine had occasioned a vision of a region cut off from access to food; in southern and western India in the late 1870s, the existence of roads and rail lines into the famine districts meant that a belief in geographic isolation did not appear as a cause in the way it had in relation to Orissa in the late 1860s.

Australia, Madagascar and elsewhere.[28] Already by the end of the 1870s, the argument that remedying “defective means of communication” would prevent famine no longer seemed entirely viable. In the middle of the great famine of 1876-8 British commentators did not, as a rule, identify a shortage of roads, canals, or railroads as to blame for famine conditions, even though they continued to maintain that investing especially in rail would alleviate famine conditions in a partial and gradual way. The Orissa famine had occasioned a vision of a region cut off from access to food; in southern and western India in the late 1870s, the existence of roads and rail lines into the famine districts meant that a belief in geographic isolation did not appear as a cause in the way it had in relation to Orissa in the late 1860s.

Most of the British men who were arguing over famine prevention and relief in 1877 advocated rail construction that would provide “direct” financial benefit to Britain while maligning the supposed ineffectiveness and costliness of irrigation projects. Even when its panegyrics to rail were strongest, their writing on famine could fatalistically maintain that famine—purportedly inevitable in India—would be at best softened by British relief efforts, making the point that Britain need not feel obliged to build unremunerative infrastructure in India because doing so would do little to eliminate famine conditions. Member of the Viceroy’s Council and the Indian Public Works Administration Andrew Clarke, for instance, voiced a version of this claim in noting that “if we cannot abolish famine—an end I fear hopeless to be attained—to do at any rate what we can to limit its area, to localize its scourge, to mitigate its intensity” (Abstract of the Proceedings 11). While voicing sympathy for those suffering, Clarke’s patience for and acceptance of the inevitability of famine conditions indicates a personal distance from the threat of famine that people at risk of starving or falling sick with cholera simply did not have. Waiting for railways magically to foster the capital that might lessen famine conditions only seems like a viable option to those who are not immediately staring down death and disease.

Unsurprisingly, the critique of views such as Clarke’s among early Indian nationalists was strident, especially as nationalists tackled the British preference for railway over canal construction. That many of the people developing famine prevention and relief policy were also railway investors was not lost on Indian writers. Especially influential in their criticism of British policy were Dadabhai Naoroji, the economist who became the first Asian Member of Parliament in Britain, and Romesh Chunder Dutt, who administered famine relief in Bengal in the 1870s as one of the first Indians to enter the civil service.[29] Both Naoroji and Dutt articulated how capital worked in empire as the source of Indian poverty and famine, though especially Naoroji imaged solutions to this problem not as the dismantling of capital as such but rather as the redirecting of capital back into India.[30] Naoroji, whose fame as an economist stemmed from theorizing and quantifying the “drain” of capital from India to Europe, took a two-pronged approach to criticizing British rail projects, simultaneously noting that rail facilitated the removal of capital from India and that the “magic wheels” of trains did not actually make food or wealth come into being.[31] Dutt, in turn, regarded the English preference for railways over canals a “geographical mistake” (India 367) drawn from the fact, first that England itself had little need for canals and second, but more importantly, the fact that “Englishmen had not appreciated the need for cheaper transit as well as for irrigation. They had not realized that securing crops in years of drought was of far more greater importance in India than means of quick transit” (India 366). In this respect, Dutt turned back to a point that irrigation advocates had made at the height of the famine: for the majority of Indian people, inexpensive transit was far more important than speedy transit.

In contrast, most British writers saw rail’s rapidity as an unalloyed good. Moreover, for many rail advocates, the fact that railways promised capital returns to British investors was a benefit rather than a problem. While most British administrators publicly deplored famine conditions and emphasized the need to redress suffering, many tended to couch their attention to famine in the logic of capitalist expansion. The British preference for railways over irrigation projects stemmed largely from the economic returns investors expected from rail. Clarke believed that, unlike slower canal transport, railways “taught the people the advantages of rapid locomotion” prized by traders and merchants (Abstract of the Proceedings 27), as though a supposed failure to appreciate trains somehow occasioned inadequate access to capital. Ignorance of the benefits of the capital that rail would fuel, Clarke suggested, was to blame for the desperate suffering of the famine years, as though admiring capital and benefiting from it surely went hand in hand. He fails, that is, to assess how it is that railways will benefit the people whose lands they crisscross.

Indeed, the actual uses of railways in famine prevention tell a quite different story than the one that Clarke envisages. Railroads did deliver grain into famine districts in the late 1870s. But the same railroads that had been designed to relieve famine only abetted the escalating prices that, in tandem with the drought, had caused famine conditions in the first place. One of the more vocal British opponents of laissez-faire famine relief, the once editor of the Madras Times William Digby, concedes that the “working power” of the railway lines “was exerted to its utmost” in accommodating grain traffic. Digby points out that even at the beginning of the famine:

the facilities for moving grain by the rail were rapidly raising prices everywhere

. . . Grain was hurriedly withdrawn by rail and sea from the more remote districts, to their serious prejudice, and poured into central depots, but retail trade up-country was almost at a stand-still. Either prices were asked which were simply beyond the means of the multitude to pay, or shops remained entirely closed. (6–7)

Digby focuses on the intra-India effects of price-gouging made possible by the removal of grain from remoter regions. These circuits, though, were not purely regional. Grain scarcity did not stop Britain from importing 1,409,000 quarters of grain from India in 1877 alone (27), such that, as Mike Davis writes, “Londoners were in effect eating India’s bread” (26–7).

It is thus less than surprising that when pro-rail arguments appeared in the London Evening Standard, relieving famine slipped readily into profitability, as though the two ran together as smoothly as the fantasy of a rail system that would somehow magically even out access to food that would, equally magically, be necessarily adequate in supply. Alongside a piece focused more squarely on irrigation, the London Evening Standard ran an article arguing that railways prevent famine effectively because they “[send] the surplus from one part to meet the deficiency in others. The land communications were the great mainstay during the recent famine, and always showed that the railways system in India was profitable and must continue to expand.” While what counts as “profit” is unclear in the sentence, the slippage in which rail’s uses in famine and more explicitly commercial meanings of “profit” is emblematic of the purported seamless conjoining of interest between British railway and manufacturing investors and Indian people starving in famine districts.[32]

Some of the staunchest arguments for rail perversely recognized that starvation and famine occur as a result, not of a shortage of food availability but of insufficient means needed to acquire it.[33] This view was deeply tied into a desire to defend the conversion to cash crops such as jute, cotton, and opium that had, under British rule, depleted the percentage of India devoted to growing grain. Clarke was among the most florid in his arguments to this effect. “The fleecy capsules of the cotton plant, or the jeweled diapers of the poppy,” Clarke opined in the Indian Legislative Council early in 1878, “feed their cultivators with no less certainty than the crops of the rice swamp, or the wheat field” (Abstract of the Proceedings 13). Clarke’s claim that opium and cotton are as likely sources of food half-understands the point that food is bought but also misrecognizes the conditions under which surplus-value is produced only for a select few off of the labor the majority of people. This fact takes on a racialized character in a colonial situation in which British capitalists extract profit from India, what Naoroji described as an economic “drain.”

In contrast, irrigation advocates highlighted that, unlike rail, canals assisted with the material practice of growing food: canals promised not only the means of cheap shipping from districts less frequently subject to periodic drought, but also irrigation of local crops. If rail’s champions had sustained the view that transportation would enable a capital expansion that would supposedly benefit all, those who favored developing irrigation infrastructure instead turned to the belief that growing more food would at least alleviate famine conditions. Most Indian commentators voiced a definitive preference for irrigation over rail construction projects; among their British supporters, Arthur Cotton, the engineer who had designed major irrigation projects in India in the 1850s (most notably the anicuts along the ![]() Godavari and

Godavari and ![]() Krishna rivers), was especially vocal on this score. At the end of the day, Cotton came back to the point that water availability would produce “entire security of food for the people” (5) by enhancing agricultural production. Cotton understood famine as a problem of misplaced British priorities around the government of India but did not question the position that adequate access to water would prevent food shortage: his is not a theory of exchange entitlements. In Cotton’s estimation, the India Office, the House of Commons, and most of the British Press demonstrated an unconscionable refusal to contemplate the importance of building canals and other irrigation works (5-6; 13-4): “it does not take five minutes’ investigation,” Cotton opined, “to prove, indisputably, that the sole cause of the Famine is the refusal to execute the Works that will give us of Water that is at our disposal” (4). Imagining a world in which Northern Indian wheat would amply feed not only India but also England, Cotton did not challenge the view that Britain should continue to imagine itself the beneficiary of capitalist agriculture in India (5). But he did make the case that, unlike railways, canal irrigation offered greater benefits to poor Indian people who stood to gain little for railway expansion. Backed by John Bright, the free trade advocate and Radical, Cotton articulated the view that railways, financed by high taxes levied on Indians, were chiefly instruments of English military power and far too costly to support the transport of grain to poor Indian people. As Bright fumed, that the question of the railways “is far more a question for the English, as a power in India, than for the native people in India” (Thorold Rogers 442).

Krishna rivers), was especially vocal on this score. At the end of the day, Cotton came back to the point that water availability would produce “entire security of food for the people” (5) by enhancing agricultural production. Cotton understood famine as a problem of misplaced British priorities around the government of India but did not question the position that adequate access to water would prevent food shortage: his is not a theory of exchange entitlements. In Cotton’s estimation, the India Office, the House of Commons, and most of the British Press demonstrated an unconscionable refusal to contemplate the importance of building canals and other irrigation works (5-6; 13-4): “it does not take five minutes’ investigation,” Cotton opined, “to prove, indisputably, that the sole cause of the Famine is the refusal to execute the Works that will give us of Water that is at our disposal” (4). Imagining a world in which Northern Indian wheat would amply feed not only India but also England, Cotton did not challenge the view that Britain should continue to imagine itself the beneficiary of capitalist agriculture in India (5). But he did make the case that, unlike railways, canal irrigation offered greater benefits to poor Indian people who stood to gain little for railway expansion. Backed by John Bright, the free trade advocate and Radical, Cotton articulated the view that railways, financed by high taxes levied on Indians, were chiefly instruments of English military power and far too costly to support the transport of grain to poor Indian people. As Bright fumed, that the question of the railways “is far more a question for the English, as a power in India, than for the native people in India” (Thorold Rogers 442).

Conclusion

While the arguments that famine resulted from excessive population or missing rail lines might seem to represent radically different ways of theorizing famine, thinking about them as wholly separate risks leaving aside how population and infrastructure were being jointly constituted in the nineteenth century. In nineteenth-century British writing, the claim that famine should be understood in relation to capital arose chiefly by the least apologetic of capitalists, namely those advocating the expansion of the Indian railways as the best means of preventing and relieving starvation. Population in such texts tends to be read as a uniform whole: rail and other infrastructure projects, that is, were imagined to benefit the population in its entirety, ignoring the distinctions between, for instance, the landless and the landed. Setting aside any thinking about the immiseration of the region’s most vulnerable people, the belief that famine was the product of some essential relationship between population and infrastructure was instrumental in rendering less visible the social relations responsible for mass starvation.

published August 2017

HOW TO CITE THIS BRANCH ENTRY (MLA format)

Frederickson, Kathleen. “British Writers on Population, Infrastructure, and the Great Indian Famine of 1876-8.” BRANCH: Britain, Representation and Nineteenth-Century History. Ed. Dino Franco Felluga. Extension of Romanticism and Victorianism on the Net. Web. [Here, add your last date of access to BRANCH].

WORKS CITED

Abstract of the Proceedings of the Council of the Governor General of India, Assembled for the Purpose of Making Laws and Regulations. 1878. XVII. Calcutta: Office of the Superintendent of Government Printing, 1879. Print.

Ambirajan, Srinivas. Classical Political Economy and British Policy in India. Cambridge: Cambridge UP, 1978. Print.

Bagchi, Amiya Kumar. Colonialism and Indian Economy. New Delhi: Oxford UP, 2010. Print.

Banerjee, Sukanya. Becoming Imperial Citizens: Indians in the Late-Victorian Empire. Durham: Duke UP, 2010. Print.

Bulwer-Lytton, Robert. “Minute by His Excellency the Viceroy, Dated Simla, 12th August 1877.” Copy of Correspondence between the Secretary of State for India and the Government of India on the Subject of the Famine in Western and Southwen India. IV. London: George Edward Eyre and William Spottiswoode, 1878. Print. East India (Famine Correspondence).

Census of England and Wales for the Year 1871 General Report. IV. London: George Edward Eyre and William Spottiswoode, 1873. Print.

Chaudhuri, Binay Bhushan. Peasant History of Late Pre-Colonial and Colonial India. VIII Part 2. New Delhi: Centre for Studies Civilizations, 2008. Print. History of Science, Philosophy and Culture in Indian Civilization.

Cotton, Arthur. The Madras Famine with Appendix Containing a Letter from Miss Florence Nightingale and Other Papers. London: Simpkin, Marshall, & Co, 1877. Print.

Davis, Mike. Late Victorian Holocausts: El Niño Famines and the Making of the Third World. London: Verso, 2002. Print.

Digby, William. The Famine Campaign in Southern India (Madras and Bombay Presidencies and Province of Mysore) 1876-1878. Vol. 1. London: Longmans Green, 1878. Print.

Drysdale, Charles R. The Population Question According to T. R. Malthus and J. S. Mill, Giving the Malthusian Theory of Over-Population. London: George Standring, 1892. Print.

Dutt, Romesh Chunder. The Economic History of India under Early British Rule: From the Rise of the British Power in 1757 to the Accession of Queen Victoria in 1837. 2nd ed. London: Kegan, Paul, Trench, Trübner & Co, 1906. Print.

—. India in the Victorian Age: An Economic History of the People. London: Kegan Paul, Trench, 1904. Print.

Fukazawa, H. “Agrarian Relations: Western India.” The Cambridge Economic History of India. Ed. Dharma Kumar and Meghnad Desai. Vol. 2. Cambridge: Cambridge UP, 1983. 177–206. Print.

Ghose, Ajit Kumar. “Food Supply and Starvation: A Study of Famines with Reference to the Indian Sub-Continent.” Oxford Economic Papers 34.2 (1982): 368–89. Print.

Hansard’s Paliamentary Debates. CCXVIII. 3rd Series. London: Cornelius Buck at the Office for Hansard’s Parliamentary Debates, 1874. Print.

Jevons, William Stanley. “Papers Set by Jevons as External Examiner at Cambridge University: Moral Sciences Tripos, Tuesday Dec 1 1874.” Papers and Correspondence of William Stanley Jevons. Ed. R.D. Collison Black. VII. London: Palgrave Macmillan, 1981. 132. Print.

Kranton, Rachel, and Anand Swamy. “The Hazards of Piecemeal Reform: British Civil Courts and the Credit Market in Colonial India.” Journal of Development Economics 58 (1999): 1–24. Print.

“Lord G. Hamilton, M.P., on the Indian Famine.” The London Evening Standard 6 Oct. 1877: 2. Print.

Malthus, Thomas. An Essay on the Principle of Population. Oxford: Oxford World Classics, 2008. Print.

Manikumar, K. A. “Impact of British Colonialism on Different Social Classes of Nineteenth-Century Madras Presidency.” Social Scientist 42.5/6 (2014): 19–42. Print.

Marx, Karl. Capital Volume II. Trans. David Fernbach. London: Penguin, 1993. Print.

Mill, John Stuart. Principles of Political Economy with Some of Their Applications to Social Philosophy. 5th ed. Vol. 1. London: Parker, Son and Bourne, 1862. Print.

Mishra, H. K. Famines and Poverty in India. New Delhi: Ashish, 1991. Print.

Mukherjee, Upamanyu Pablo. Natural Disasters and Victorian Empire. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, 2013. Print.

Naidu, A. Nagaraja. “Famines and Demographic Crisis–Some Aspects of the De-Population of Lower Castes in Madras Presidency, 1871-1921.” Dalits and Tribes of India. Ed. J. Cyril Kanmony. New Delhi: Mittal, 2010. Print.

Naoroji, Dadabhai. “Memorandum on Mr. Danvers’s Papers of 28th June 1880 and 4th January 1879.” Essays, Speeches, Addresses and Writings on Indian Politics of the Honorable Dadabhai Naoroji. Bombay: Caxton Printing Works, 1887. 441–64. Print.

Nayak, Ganeswar. “Transport and Communication System in Orissa.” Economic History of Orissa. Ed. Nihar Ranjan Patnaik. New Delhi: Indus Publishing, 1997. 345–55. Print.

“Neglected Aspects of the Indian Famine.” The Economist 28 Mar. 1874: 378–9. Print.

Phule, Jotirao. “Cultivator’s Whipcord.” Selected Writings of Jotirao Phule. Ed. G.P. Deshpande. Trans. Aniket Jaaware. New Delhi: LeftWord, 2002. Print.

Rangasami, Amrita. “‘Failure of Exchange Entitlements’ Theory of Famine: A Response.” Economic and Political Weekly XX.42 (1985): 1797–1801. Print.

Ray, Urmita. “Subsistence Crises in Late Eighteenth and Early Nineteenth Century Bihar.” Social Scientist 41.3/4 (2013): 3–18. Print.

Report of the Indian Famine Commission: Part II Measures of Protection and Prevention. London: George Edward Eyre and William Spottiswoode, 1880. Print.

Ricardo, David. The Principles of Political Economy and Taxation. 3rd ed. London: John Murray, 1821. Print.

Roy, Parama. Alimentary Tracts: Appetites, Aversions, and the Postcolonial. Durham: Duke UP, 2010. Print.

Saha, Poulomi. Object Imperium: Gender, Affect, and the Making of East Bengal. MS.

Samal, J. K. Economy of Colonial Orissa 1866-1947. New Delhi: Munshiram Manoharlal, 2000. Print.

Sami, Leela. “Gender Differentials in Famine Mortality: Madras (1876-78) and Punjab (1896-97).” Economic and Political Weekly 37.26 (2002): 2593–2600. Print.

Schabas, Margaret. The Natural Origins of Economics. Chicago: U of Chicago P, 2007. Print.

Sen, Amartya. “Imperial Illusions.” The New Republic 31 Dec. 2007: 28. Print.

—. Poverty and Famines: An Essay on Entitlement and Deprivation. Oxford: Oxford UP, 1983. Print.

Sweeney, Stuart. Financing India’s Imperial Railways 1875-1914. New York: Routledge, 2016. Print.

—. “Indian Railways and Famine 1875-1914: Magic Wheels and Empty Stomachs.” Essays in Economic & Business History 26 (2008): 147–57. Print.

“The Famine in India.” Manchester Courier and Lancashire General Advertiser 5 June 1877: 6. Print.

Thorold Rogers, James, ed. Public Addresses by John Bright, M.P. London: Macmillan, 1879. Print.

Wakimura, Kouhei. “The Indian Economy and Disasters during the Late Nineteenth Century: Problems of Interpretation of Colonial Economy.” The BRICs as Regional Economic Powers in the Global Economy. Ed. Takahiro Sato. Sapporo: Slavic-Eurasian Research Center, 2012. Print.

“War and Famine.” Leicester Chronicle and Leicestershire Mercury 8 Sept. 1877: 4. Print.

Williams, A. Lukyn. Famines in India: Their Causes and Possible Prevention. London: Henry S. King, 1876. Print.

ENDNOTES

[1] Davis summarizes the claims about the mortality during the Indian famines of 1876-9 by noting that William Digby’s 1901 ‘Prosperous’ British puts the number at 10.6 million; Arap Maharatna’s The Demography of Famine (1996) at 8.2 million and Roland Seavoy’s Famine in Peasant Societies (1986) at 6.1 million (Davis 7).

[2] On the depopulation of landless castes during the famine, see Naidu 36.

[3] See Davis 33.

[4] On the significance of American cotton for cultivators in India, see Kranton and Swamy 6.

[5] On the consequences of conversion to cash crops and difficulties of converting fields to new crops in times of distress, see Manikumar 25.

[6] On the Deccan riots, see Fukazawa 194–5.

[7] As Amiya Bagchi points out, the British government would “curb” property rights in order to secure the land revenue that financed the imperial state (196).

[8] Binay Chaudhuri emphasizes, against earlier critics, that little property was formerly transferred to moneylenders during and immediately after the famine years. According to Chaudhuri, this lack of formal transfer occurred because the moneylending vanis were from non-cultivating castes, and because mortgaging rather than purchasing land would allow they control of the produce of the land without taking on the obligations associated with land-ownership (539).

[9] G.P. Deshpande notes that “Cultivator’s Whipcord (Shetkaryacha Asud) was written in 1883 but the publication of the entire text was delayed because, as Phule put it, ‘We the shudras have amongst us cowardly publishers’. Nor was it written at one go. Phule did public readings of the various chapters of the book as they got written” (113).

[10] Writing about William Digby’s exposé of the southern Indian famine, for instance, Mukherjee emphasizes that Digby was particularly deft at “the vivid representation of the decayed, dying and abject Indian bodies—people following rice carts to nibble at the grain that fell from it; a family starving to death in sight of thousands of bags of grain that had been hoarded and priced beyond their reach; dogs fighting over the bloated corpse of a young child, and above all, the skeletal specters of the famished” (44).

[11] Among Malthusians in Britain, in turn, Indian famine offered a clear example of the Essay’s precepts. The doctor Charles Drysdale—the Malthusian League’s co-founder and first President—observed of the 1876-8 famine that “it would be a wonder” if famines were not “endemic in that over-peopled country” (90). For Drysdale and many others, the famines of the 1870s seemed to offer material evidence of Malthus’s hypothesis.

[12] Parama Roy observes that the British response to famine “relief” during this period entailed “dislocating starving populations from their homes and aggregating them in dormitory camps, demanding hard labor of the recipients as a condition of their receipt of food, and imposing a ‘distance test’ that denied work to able-bodied men and older children within ten miles of their homes” (117).

[13] Mike Davis notes that the Temple wage “provided less sustenance for hard labor than the diet inside the infamous Buchenwald concentration camp and less than half of the modern caloric standard recommended for adult males by the Indian government” (38).

[14] Kouhei Wakimura makes the point that “we need to analyze the specific causes of death in order to understand why famines brought about huge human mortality. We find that more deaths were due to diseases than starvation. Such diseases as cholera, smallpox, diarrhea, dysentery, and malaria combined with famine to produce large-scale mortality” (79). See also Davis 110.

[15] Dutt follows even Warren Hastings’ claim that a full third of the population of Bengal died as a result of the famine (Ray 7). Sen reports that, while the famine was certainly catastrophic, a third is perhaps an overestimate.

[16] While Ricardo’s Principles were, over the course of the 1870s, gradually becoming supplanted by the new neoclassical marginalism of William Stanley Jevons and others, Ricardian economics nonetheless retained high degrees of influence on the economic thinking apparent in administrative policy writing and in the popular press throughout the 1870s. Ricardo writes that “It is only then because land is of different qualities with respect to its productive powers, and because in the progress of population, land of an inferior quality, or less advantageously situated, is called into cultivation, that rent is ever paid for the use of it. When, in the progress of society, land of the second degree of fertility is taken into cultivation, rent immediately commences on that of the first quality, and the amount of that rent will depend on the difference in the quality of these two portions of land” (57). John Stuart Mill was responsible for the theory’s popularity through midcentury. Mill writes that “Settlers in a new country invariably on the high and thin lands; the rich but swampy soils of the river bottoms cannot at first be brought into cultivation, by reason of their unhealthiness, and of the great prolonged labor for clearing and draining them” (178). While Mill cites the American political economist H. C. Carey as the source of this view, its basis in Ricardian thinking on ground rent remains clear.

[17] Margaret Schabas observes that “Jevons was the first to explore the question of the dimensions of economic variables, and he found that, in many cases, the physical component dropped out of the analysis.

. . . Indeed, the material attributes of goods are of no consequence to the analysis” (13).

[18] In Famine in India, Arthur Lukyn William suggests that “in England, as has been observed, there is always a natural scarcity of food, but the ‘actual pressure’ is never felt; because, as Dr. Hunter says, ‘The whole tendency of modern civilization is to raise up intervening influences which render the relation of annual pressure to natural scarcity less certain and less direct, until the two terms which were once convertible come to have very little connection with each other” (15).

[19] The Famine Commission listed ![]() Oudh [Awadh] has more densely populated than Bengal, but then noted that “The average in the case of Bengal and the North-Western Provinces is brought down by the large area of mountainous and thinly peopled hill country. . . In Bengal there are 17 districts in which the population is over 500 to the square mile” (Report of the Indian Famine Commission: Part II Measures of Protection and Prevention 86). In these districts, “the population that it presses closely on the means of subsistence, and here unless the existing system of agriculture is improved, so as to yield a larger produce per acre, there is no room for an increase of the population” (77). Arthur Lukyn Williams, in a prize-winning Cambridge essay, noted that while Assam and Chota Nagpur remain thinly populated, “the food-producing area cannot average less than 650 souls to the square mile. . . . Yet great as is this density of population, Sir R. Temple shows that it is not at present too much for the land” (74-5).

Oudh [Awadh] has more densely populated than Bengal, but then noted that “The average in the case of Bengal and the North-Western Provinces is brought down by the large area of mountainous and thinly peopled hill country. . . In Bengal there are 17 districts in which the population is over 500 to the square mile” (Report of the Indian Famine Commission: Part II Measures of Protection and Prevention 86). In these districts, “the population that it presses closely on the means of subsistence, and here unless the existing system of agriculture is improved, so as to yield a larger produce per acre, there is no room for an increase of the population” (77). Arthur Lukyn Williams, in a prize-winning Cambridge essay, noted that while Assam and Chota Nagpur remain thinly populated, “the food-producing area cannot average less than 650 souls to the square mile. . . . Yet great as is this density of population, Sir R. Temple shows that it is not at present too much for the land” (74-5).

[20] Famine mortality statistics varied widely. Davis notes that official records for the 1873-4 Bengal famine claim that only 23 people died of starvation; regardless of mortality numbers, scholars agree that the response, to quote Davis, “was the only truly successful British relief effort in the nineteenth century” with its provision of a “gratuitous dole,” relief works, and importation of emergency rice from Burma (36).

[21] Many starvation deaths were reported as cholera deaths because it was more palatable to the British administration. See Davis 34.

[22] Examining the technology of the 1871 imperial census of India on the economics of Bengali, Poulomi Saha points out that the census offered “evidence” of the idea that “Bengal meted out its communal population . . . along the very axis of rural dependence and urban development”. See Object Imperium: Gender, Affect, and the Making of East Bengal (manuscript).

[23] Although it was more sympathetic to giving aid than The Economist, the Leicester Chronicle borrowed the former’s reasoning in holding British rule responsible for causing, through supposed prosperity, the population growth that it held responsible for the famine. “The appeal comes,” the Chronicle observes, “from fellow-subjects, from those whose growth of population we have somewhat abnormally encouraged” (“War and Famine” 4).

[24] Davis notes that “We are not dealing, in other words, with ‘lands of famine becalmed in stagnant backwaters of world history, but with the fate of tropical humanity at the precise moment (1870-1914) when its labor and products were being dynamically conscripted into a London-centered world economy. Millions died, not outside the “modern world system,’ but in the very process f being forcibly incorporated into its economic and political structures” (8–9).

[25] See, for instance, coverage in the Manchester Courier (“The Famine in India” 6)

[26] “It has been suggested that, during the Orissa famine, the deaths and misery were not due to non-intervention on the part of the government as such, but due to the difficulties of transportation: firstly there were no good roads to move foodgrains from adjoining areas, and secondly the heavy monsoon that came so soon after the severe famine prevented even the use of sea-transport. There were practical difficulties, no doubt . . . But after reading the mass of correspondence and official papers of the period, one cannot resist the conclusion that the officials as a class swore by the principles of non-interference in the grain market” (Ambirajan 76–7).

[27] On the lack of roads in Orissa, see Mishra 10. J. K. Samal reports that “The grave deficiency of communications, which still existed as late as 1866, was made apparent in the great Orissa Famine, when it was said that ‘the people were shut in between pathless jungles and impracticable seas, and were like passengers in a ship without provisions.’ After the famine, British authority felt the urgent need for taking positive steps for developing road system in Orissa” (74–5).

[28] Marx notes that “the sudden increase in the demand for cotton, jute, etc., due to the American Civil War led to a great limitation of rice cultivation in India, a rise in the price of rice, and the sale of old stocks of rice by the producers. On top of this, there was the unparalleled export of rice to Australia, ![]() Madagascar, etc., in 1864-4. Hence the acute character of the famine of 1866, which carried off a million people in Orissa alone” (218). On the conversion to cash crops such as jute and cotton, see also Saha.

Madagascar, etc., in 1864-4. Hence the acute character of the famine of 1866, which carried off a million people in Orissa alone” (218). On the conversion to cash crops such as jute and cotton, see also Saha.

[29]As Stuart Sweeney observes, “generous government rail budgets were out of kilter with investment in irrigation and general industrial development” (“Indian Railways” 148).

[30]Davis notes that while Naoroji and Dutt published the most famous of their claims at the beginning of the twentieth century, their “basic polemical strategy—mowing down the British with their own statistics” was already in place in the 1870s (56); indeed, Davis observes, Naoroji read “The Poverty of India” in 1876 in ![]() Bombay, in advance of publishing Poverty and Un-British Rule in India in 1901 (56).

Bombay, in advance of publishing Poverty and Un-British Rule in India in 1901 (56).

[31] Naoroji writes that “If the mere movement of produce can add to existing wealth, India can become rich in no time. All it would have to do, is to go on moving its produce continually over India, all the year round, and under the magic wheels of the train, wealth will go on springing, till the land will not suffice to hold it. But there is no Royal (even railway) road to material wealth. It must be produced from the materials of the Earth till the great discovery is made of converting motion into matter” (444). As Sukanya Banerjee points out, “it is not so much the extraction of wealth that Naoroji criticizes, but the patterns of circulation into which that wealth is routed (or not)” (47–8). On Naoroji and railways, see also Sweeney, Financing India’s Imperial Railways 1875-1914 44.

[32]Sweeney points out, “representatives of the British manufacturing and service sectors benefited from famine protective railway construction. By contrast, the amount of imported material involved in the construction of canals and water tanks for irrigation was negligible” (“Indian Railways” 152).

[33] Sen argues that “starvation . . . is a function of entitlements and not of food availability as such. Indeed, some of the worst famines have taken place with no significant decline in food availability per head” (Poverty and Famines 7).