Abstract

The years 1808-1809 mark a major period of transition in English National Theatre. In the space of just a few months, London’s two patent playhouses—the Theatres Royal Covent Garden and Drury Lane—burned to the ground. The devastation was total and complete. This article tells the story of the two theatre fires and explores their economic, political, and cultural repercussions, direct and indirect, including the reconstruction of Covent Garden and Drury Lane, the Old Price Riots, and the career dénouements of Richard Brinsley Sheridan, John Philip Kemble, Sarah Siddons, and Dorothy Jordan. In the process of providing a historical and graphic overview, it proposes that the London Theatre fires of 1808-1809 not only created significant professional and financial turmoil but also helped to engender a shift from an eighteenth-century to a nineteenth-century theatrical paradigm.

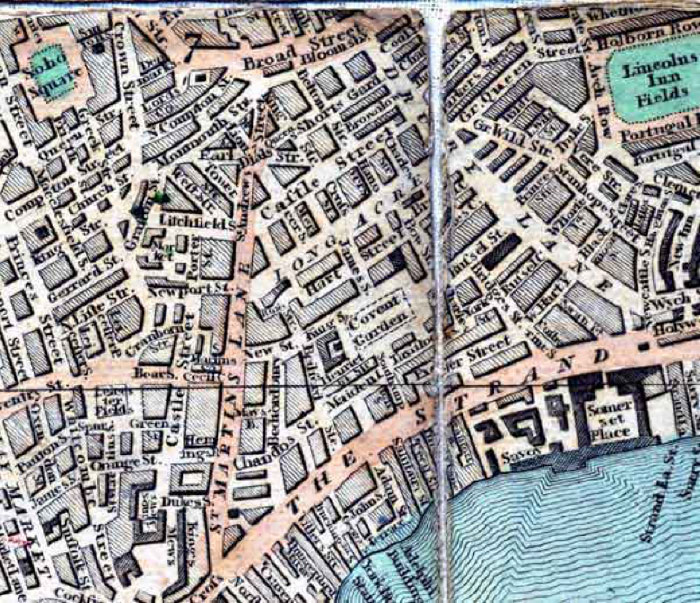

Figure 1: 1807 map of London: Covent Garden Theatre is the L-shaped building in the northeast corner of the open square marked “Covent Garden.” Drury Lane Theatre is the black rectangle at the middle right of the image, nestled between Drury Lane, Russell Street, and Bridges St. (courtesy of the Thomas Fisher Rare Book Library, U of Toronto).

CONFLAGRATION

Who burnt (confound his soul) the houses twain

Of Covent Garden and of Drury Lane?– W.T.F. “Loyal Effusion,” Rejected Addresses: or the New Theatrum Poetarum, p.3

Figure 2: [William Capon], The Ruins of Old Covent Garden Theatre – after the Fire, 1808 (1808, © Victoria and Albert Museum, London)

The blaze broke out around four o’clock in the morning of 20 September 1808. It cracked and sizzled its way through London’s ![]() Theatre Royal, Covent Garden, consuming everything in its path and roaring out into the neighboring roads of Bow Street and Hart Street (Fig. 1). The season had begun with performances of Shakespeare’s Macbeth and James Kenney’s hit farce Raising the Wind (1803); now, only twelve days later, the Theatre was offering a different kind of show. People clambered onto their rooftops to observe the radiant spectacle and to extinguish the threatening cinders falling upon their homes. “The dreadful conflagration,” a report in the Morning Chronicle attests, “had a most impressively grand and beautiful effect. From the extent and hollow nature of the building, and immense quantity of oiled canvas, the flames formed an upright column rising to a tremendous height in the atmosphere, and sending out sparks that spread a shower of fire all around” (21 September 1808). Attempts by firemen to subdue the blaze were thwarted due to a lack of hose length and a water shortage: the supply from the main pipe had been cut off in preparation for its replacement, and they were without water for over an hour. In the meantime, the inferno leveled the playhouse, a local pub called the Strugglers, and seven to nine adjacent houses in under three hours. The result, according to the contemporary biographer James Boaden, was “a mass of flaming ruins” (Kemble 2: 452) (Fig. 2). The conflagration claimed the lives of twenty-two people, three from the Phoenix Fire Office (Fig. 3) who perished when the roof of the Theatre crashed down upon them (2: 457, 454). Though the books, accounts, deeds, and cash in the Theatre’s treasury were preserved, nothing else remained. The fire destroyed all of the Theatre’s material assets: elaborate sets, props, decorations, costumes, jewelry, dramatic scripts, and musical scores, including original compositions of George Frideric Handel and Thomas Arne.

Theatre Royal, Covent Garden, consuming everything in its path and roaring out into the neighboring roads of Bow Street and Hart Street (Fig. 1). The season had begun with performances of Shakespeare’s Macbeth and James Kenney’s hit farce Raising the Wind (1803); now, only twelve days later, the Theatre was offering a different kind of show. People clambered onto their rooftops to observe the radiant spectacle and to extinguish the threatening cinders falling upon their homes. “The dreadful conflagration,” a report in the Morning Chronicle attests, “had a most impressively grand and beautiful effect. From the extent and hollow nature of the building, and immense quantity of oiled canvas, the flames formed an upright column rising to a tremendous height in the atmosphere, and sending out sparks that spread a shower of fire all around” (21 September 1808). Attempts by firemen to subdue the blaze were thwarted due to a lack of hose length and a water shortage: the supply from the main pipe had been cut off in preparation for its replacement, and they were without water for over an hour. In the meantime, the inferno leveled the playhouse, a local pub called the Strugglers, and seven to nine adjacent houses in under three hours. The result, according to the contemporary biographer James Boaden, was “a mass of flaming ruins” (Kemble 2: 452) (Fig. 2). The conflagration claimed the lives of twenty-two people, three from the Phoenix Fire Office (Fig. 3) who perished when the roof of the Theatre crashed down upon them (2: 457, 454). Though the books, accounts, deeds, and cash in the Theatre’s treasury were preserved, nothing else remained. The fire destroyed all of the Theatre’s material assets: elaborate sets, props, decorations, costumes, jewelry, dramatic scripts, and musical scores, including original compositions of George Frideric Handel and Thomas Arne.

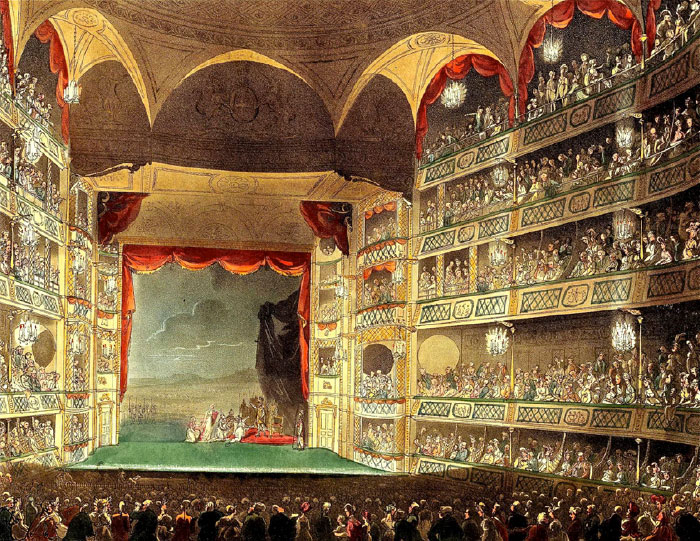

Figure 3 (left): James Pollard, engraved by Richard Gilson Reeve, _London Fire Engines: The noble protectors of lives and property_ (1823, courtesy of the ![]() British Museum). The Phoenix Fire Office is represented as the central green wagon drawn by white horses, with firemen wearing buff-colored livery. Figure 4 (right): Thomas Rowlandson and Augustus Charles Pugin, Covent Garden Theatre (1808), Plate 27 of Rudolph Ackermann, _The Microcosm of London; or, London in Miniature_ (1808-10, courtesy of the Thomas Fisher Rare Book Library, U of Toronto), 1: 212-13. This image, created just before the theatre burned down, depicts the interior of the theatre with Handel’s organ at its center.

British Museum). The Phoenix Fire Office is represented as the central green wagon drawn by white horses, with firemen wearing buff-colored livery. Figure 4 (right): Thomas Rowlandson and Augustus Charles Pugin, Covent Garden Theatre (1808), Plate 27 of Rudolph Ackermann, _The Microcosm of London; or, London in Miniature_ (1808-10, courtesy of the Thomas Fisher Rare Book Library, U of Toronto), 1: 212-13. This image, created just before the theatre burned down, depicts the interior of the theatre with Handel’s organ at its center.

Other significant losses included the organ that Handel had used at Covent Garden in the 1730s and 40s (Fig. 4), the wine stores of the Beefsteak Club, and the wardrobe of the great tragic actress Sarah Siddons (1755-1831; Fig. 5), which featured, amongst other treasures, a voluminous lace veil that had once belonged to Marie Antoinette. The worth of Handel’s organ was estimated at 1000 guineas, the wines at £1500, and the lace of the late Queen at £1000 (Boaden, Kemble 2: 456, Wyndham 1: 328)—today’s near equivalent of £35,700, £51,000, and £34,000, respectively.[1] In truth, such goods were priceless, and Siddons suggests as much in a letter to Lady Harcourt: “I have lost everything, all my jewels and lace, which I have been collecting for thirty years, and which I could not purchase again, for they were all really fine and curious. . . . In short, everything . . . is gone, and literally not one vestige of all that has cost me so much time and money to collect” (qtd. Wyndham 1: 328-29). There was no replacing what had been ruined; there was no going back. Siddons communicates this in a letter to Lady Perceval: “I have lost every article of stage ornament that I had in the world, and my poor brother all he possessd—and he has nearly to begin the world again” (2). Here, Siddons refers to her brother John Philip Kemble (1757-1823; Fig. 6), fellow actor and manager of Covent Garden Theatre. For Kemble, the fire precipitated a series of misfortunes that would afflict him for over a year to come.

Figure 5 (left): Gilbert Stuart, Sarah Siddons (née Kemble) (1787), © National Portrait Gallery, London. Figure 6 (right): William Beechey, John Philip Kemble (1798-99), by permission of the Trustees of Dulwich Picture Gallery

Little more than five months later, on the evening of 24 February 1809 and only a couple of blocks away from Covent Garden, fire erupted in London’s Theatre Royal, Drury Lane (Fig. 7).

Figure 7: Thomas Rowlandson and Augustus Charles Pugin, Drury Lane Theatre (1808), Plate 32 of Rudolph Ackermann, _The Microcosm of London_ 1: 228-29. This image, created just before the theatre burned down, depicts the stage and auditorium of the theatre (courtesy of the Thomas Fisher Rare Book Library, U of Toronto)

A passer-by spotted the smoke and flickering light around half past ten o’clock at night. Spreading swiftly and without restraint through the dry timber architecture (the iron curtain separating the stage from the house had been removed due to rust and rot), the fire whipped its way through the cavernous auditorium. By eleven o’clock, it had completely engulfed the grand building. As the flames billowed into the air, they cast a sublime light upon the dark metropolis (Figs. 8 and 9).

Figure 8 (left): Thomas Luny, The Burning of Drury Lane Theatre from ![]() Westminster Bridge (c.1809). This image depicts the London skyline from Westminster Bridge, with Drury Lane in flames at its center. Also depicted are the spires of St. Martin-in-the-Fields, St. Giles-in-the-Fields, St. Mary-le-Strand, St. Clement Danes; the York Building Waterworks Company tower; and the facades of the Royal Terrace, Adelphi and Somerset House (© Museum of London). Figure 9 (right): Abraham Pether, Old Drury Lane Theatre on Fire 1809 (24 February 1809, Guildhall Art Gallery, City of London)

Westminster Bridge (c.1809). This image depicts the London skyline from Westminster Bridge, with Drury Lane in flames at its center. Also depicted are the spires of St. Martin-in-the-Fields, St. Giles-in-the-Fields, St. Mary-le-Strand, St. Clement Danes; the York Building Waterworks Company tower; and the facades of the Royal Terrace, Adelphi and Somerset House (© Museum of London). Figure 9 (right): Abraham Pether, Old Drury Lane Theatre on Fire 1809 (24 February 1809, Guildhall Art Gallery, City of London)

A crowd gathered to watch: “Russell Street, Drury Lane, Catherine Street, Bow Street, Tavistock Street, Long Acre, and Covent Garden were absolutely filled” (Daniel and Dolby 4: 58). People in all directions climbed up to their rooftops or stood on the Blackfriars and Westminster Bridges to view the incandescent scene. The actress and dramatist Elizabeth Inchbald, viewing the fire from her room, wrote that it was “a prospect more beautiful, more brilliantly and calmly celestial, than ever met my eye. . . . [T]he river, the houses on its banks, the ![]() Surrey hills beyond, every boat upon the water, every spire of a church,

Surrey hills beyond, every boat upon the water, every spire of a church, ![]() Somerset House and its terrace on this side—all looked like one enchanted spot, such as a poet paints, in colours more bright than nature ever displayed in this foggy island” (qtd. Boaden, Inchbald 2: 132). Another commentator observed:

Somerset House and its terrace on this side—all looked like one enchanted spot, such as a poet paints, in colours more bright than nature ever displayed in this foggy island” (qtd. Boaden, Inchbald 2: 132). Another commentator observed:

The spectacle of real desolation which the structure afforded, when contemplated from Blackfriars-bridge at 12 o’clock, far surpassed in magnificence any of the mimic representations which were ever viewed within its walls. The shell of the building was then entire, and the upper range of windows and the balustrade above, forming the whole length of the edifice, being raised above all the adjoining buildings, and thrown into strong relief by the flame, resembled the antient [sic] aqueducts which are still remaining in the south of Europe. . . . Thus the effect was rather that of an elaborate work of art. (The Times 25 February 1809)

Figure 10: John Russell, Richard Brinsley Sheridan (1788, © National Portrait Gallery, London)

Figure 11: John Hoppner, Mrs Jordan as Hypolita in ‘She Would and She Would Not’ (exhibited 1791; © Tate, London 2015)

RECONSTRUCTION

I sing of the singe of Miss Drury the first,

And the birth of Miss Drury the second.– M.G.L. “Fire and Ale,” Rejected Addresses: or the New Theatrum Poetarum, p.68

Kemble may have considered himself on the brink of ruin, but he was a man of resources. After the burning of Covent Garden Theatre, friends came quickly to his aid—among them, the Duke of Northumberland, who, as a gesture of gratitude for Kemble’s once having given lectures in elocution to his son, offered Kemble a bond for £10,000. Kemble demurred, citing his current financial situation and fears that he may be unable to repay the loan punctually, but the Duke assured Kemble that he need not be concerned on this score, and Kemble accepted the offer. Thus encouraged, Kemble sprang into action, and only six days after the destruction of Covent Garden Theatre the company performed at the King’s Theatre. Before the performance, and after a rousing chorus of God Save the King, Kemble expressed his gratitude for the public’s suffering English drama to be performed in a theatre that regularly featured Italian opera, and announced his aim to reopen Covent Garden within the year (Morning Chronicle 27 September 1808). Robert Smirke was appointed architect, and an additional sum of £50,000 was raised in shares of £500 each (Morning Chronicle 7 November 1808). This, in combination with the bond from the Duke and the insurance from the fire offices, did not cover the cost entirely, later reported at £150,000 (Ackermann 3: 264), but it was a promising start.

Figure 12: Thomas Lawrence, King George IV (c.1814, © National Portrait Gallery, London)

Figure 13: James Gillray, Theatrical Mendicants relieved—“have Pity upon all our Aches & Wants!” (15 January 1809). The title plays on Kemble’s much criticized pronunciation of the word “aches” with two syllables—as “aitches” and not as “aiks.” The text above the image says, “New Dramatic Resource—a Begging we will go!—a Scene from Covent Garden Theatre after the Conflagration.” The print depicts a crucifix-wearing Kemble, in the company of his brother Charles Kemble and his sister Sarah Siddons, wearing fashionable dress and begging from an obese Duke of Northumberland, who places into Kemble’s hat a “Draft for 10,000 Pounds [signed] Northumberland.” In Kemble’s right hand is a paper that reads, “Donations—Duke of Nord £10000 —Marqs of Abern £1000—Lord Egotist [Erskine] £1000—.” Siddons carries a large reticule on which is written, “Humble Solicitations to the Humane & Benevolent” out of which promissory notes project and fall to the ground and are inscribed, “‘the most Noble Marquiss of Abercorn’, ‘The Rt honb Lord Ego— Lord Mountjoy, Duke of —’, ‘The Right Honl Lord Castler[eagh]’, ‘His Roy[al Highness] the Prin[ce of Wales’].” A Harlequin and a zany or fool dance behind the three siblings, rejoicing in the burning of the Theatre, in the family’s pecuniary successes, or both (courtesy of the British Museum)

Later that same day, Kemble attended a dinner with his fellow Covent Garden proprietors, friends, and Freemasons, during which he announced that the Duke of Northumberland had just sent him a message, asking him to burn the bond (now cancelled) that Kemble had previously signed for £10,000—an act that made Kemble the recipient of the funds, free and clear. This transformation of a loan into a gift was a major boon for Kemble and, no doubt, for the Duke’s social prestige. The graphic artist James Gillray lampooned the gesture in his Theatrical Mendicants relieved—“have Pity upon all our Aches & Wants!” (Fig. 13). With its portrayal of the wealthy relieving the wealthy, the image implies that self-aggrandizing aristocrats misdirect their funds: there are other, worthier objects of charity than the already affluent Kemble family.

Figure 14: Thomas Rowlandson and Augustus Charles Pugin, New Covent Garden Theatre (1810), Plate 100 of Rudolph Ackermann, _The Microcosm of London; or, London in Miniature_ (1808-10, courtesy of the Thomas Fisher Rare Book Library, U of Toronto), 1: 262-63. This building opened in 1809 to replace its predecessor, which had burned down in 1808. The image depicts the third tier of boxes as well as the “pigeon holes” above the gallery

If Gillray’s satire reflected public sentiment, such objections failed to weaken Kemble’s resolve. Smirke’s grand Greek Revival building, the portico of which was modeled on the Temple of Athena in ![]() the Acropolis, was constructed in only nine months. The auditorium of the new Theatre (Fig. 14) featured a number of “improvements,” including additional space in the pit; the conversion of the third tier into a series of private luxury boxes, each with its own ante-room; and the transformation of the one-shilling or upper gallery into a series of arched openings or “pigeon holes” beneath the roof. Kemble and his fellow proprietors hoped to attract wealthy patrons with the addition of the private boxes, each which could be rented at £300 per year (nearly £10,200 today) (Genest 8: 171), and the hire of an opera star—the Italian soprano Angelica Catalani—at the costly sum of £75 per night (Baer 27). As a means to recover construction expenditures and to ensure future revenue, they raised ticket prices from six to seven shillings for the regular boxes, and from three shillings and sixpence to four shillings for seats in the pit. The Morning Chronicle for 14 September 1809 announced that the newly built Theatre Royal, Covent Garden would open on September 18th, two days before the one-year anniversary of the fire, with Macbeth, starring John Philip Kemble and Sarah Siddons. This notice followed:

the Acropolis, was constructed in only nine months. The auditorium of the new Theatre (Fig. 14) featured a number of “improvements,” including additional space in the pit; the conversion of the third tier into a series of private luxury boxes, each with its own ante-room; and the transformation of the one-shilling or upper gallery into a series of arched openings or “pigeon holes” beneath the roof. Kemble and his fellow proprietors hoped to attract wealthy patrons with the addition of the private boxes, each which could be rented at £300 per year (nearly £10,200 today) (Genest 8: 171), and the hire of an opera star—the Italian soprano Angelica Catalani—at the costly sum of £75 per night (Baer 27). As a means to recover construction expenditures and to ensure future revenue, they raised ticket prices from six to seven shillings for the regular boxes, and from three shillings and sixpence to four shillings for seats in the pit. The Morning Chronicle for 14 September 1809 announced that the newly built Theatre Royal, Covent Garden would open on September 18th, two days before the one-year anniversary of the fire, with Macbeth, starring John Philip Kemble and Sarah Siddons. This notice followed:

The proprietors having completed the new Theatre within the time originally promised, beg leave respectfully to state to the Public the absolute necessity that compels them to make the following advance on the prices of admission:—Boxes, 7s. Half Price, 3s. 6d.; Pit, 4s. Half Price, as usual; the Lower and Upper Galleries will remain at the old prices. . . . [T}he Proprietors persuade themselves that in their proposed regulation they shall be honoured with the concurrence of an enlightened and liberal public.

Figure 15: Samuel William Reynolds, after John Opie, Samuel Whitbread (1806, © National Portrait Gallery, London)

The reconstruction of Drury Lane was a far more complicated matter. The Theatre was already on the brink of bankruptcy, and for Sheridan “to struggle with the old debt, incur a new one, and rebuild his theatre was,” Boaden remarked, “utterly impossible” (Kemble 2: 483). The Morning Chronicle phrased it this way: “The debt due to Renters, Box-owners, Annuitants, Ticket-holders, Performers and Tradesmen is so considerable, that a new Theatre on the same scite [sic], in which all their interests shall be revived, could not be carried on with a profit; for in addition to the amount of their demands, a sum of 150,000l. at least would be required to re-establish the structure” (27 February 1809). Sheridan’s inability to turn a profit in the old Theatre had also lost him the confidence of wealthy patrons who might have come to his aid. By the time that Covent Garden reopened in 1809, little progress had been made other than the fact that the Drury Lane company was now situated at the Lyceum Theatre, where they would perform for the next three seasons: 1809-1810, 1810-1811, and 1811-1812.

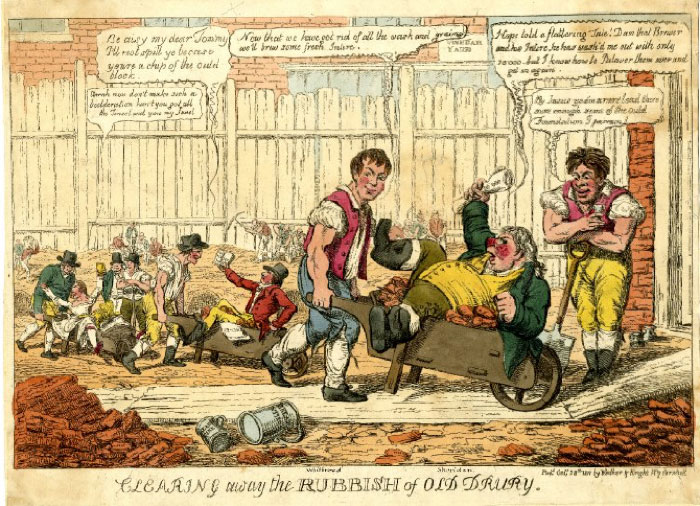

Figure 16: Charles Williams, Clearing away the Rubbish of Old Drury (28 October 1811). A bloated, grizzled, and rhinophymic-nosed Sheridan lies in a wheelbarrow pushed by Samuel Whitbread (dressed in worker’s clothes) who exclaims, “Now that we have got rid of all the wash and grains we’ll brew some fresh Intire.” Whitbread was the only son of Samuel Whitbread (1720-1796), English politician and brewer, who established a brewery that in 1799 became Whitbread & Co. Ltd. It is this lucrative legacy, from which the younger Whitbread benefited, that Williams plays upon here, as indicated further in the two silver tankards labeled “Whitbreads Intire.” “Intire” was an early synonym for porter; it was coined “entire” from its being drawn direct from a single cask, rather than being a mixture of more than one product. In the foreground, Sheridan holds in his hand a paper inscribed “20’000”, the near amount he received for his share in the Theatre, and complains, “Hope told a flattering Tale! Dam that Brewer and his Intire, he has wash’d me out with only 20’000. but I Know how to Palaver them over and get in again.” His son Tom is being carried away in a wheelbarrow with a note attached to it for “12,000”; the man pushing him says, “Be aisy my dear Tommy I’ll not spill ye becase ye are a chip of the ould block.” To the right, a laborer leans on his shovel and remarks to the man lugging Sheridan, “By Jasus you’ve a rare load there sure enough some of the Ould Foundation I parceave!” (courtesy of the British Museum)

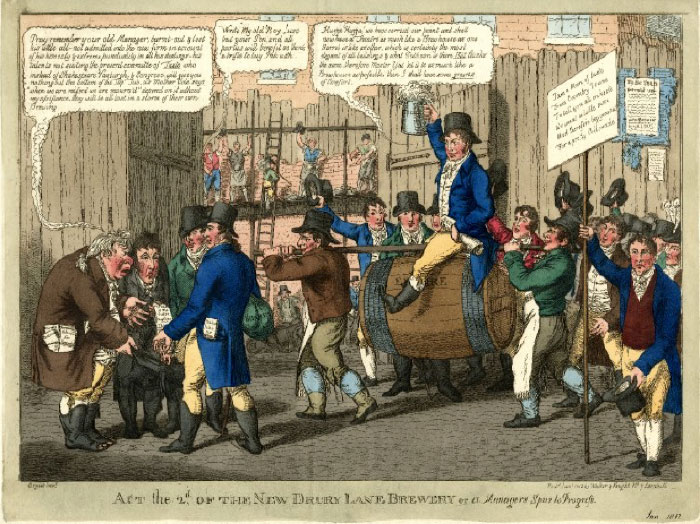

Figure 17: Charles Williams, Act the 2.d of the New Drury Lane Brewery or a Managers Spur to Progress (January 1812). At the center of the image, Samuel Whitbread hoists an eponymous tankard in his right hand and sits atop a large cask marked “En[t]ire,” which is carried by two draymen. In his left hand, Whitbread grasps the new Theatre “Pat[en]t” and cries out, “Huzza! Huzza! we have carried our point and shall now have a Theatre as much like a Brewhouse as one Barrel is like another, which is certainly the most elegant of all buildings & what Publican is there But thinks the same, therefore Master Yat [Wyatt] let it be as much like a Brewhouse as possible, then I shall have some grains of Comfort.” Among other figures is Sheridan, in profile on the far left, with toes protruding through his boots and manuscripts spilling out of his pocket—the latter marked with names of his dramas _The School for Scandal_, _The Duenna_, and _The Rivals_. In hopes of charity from the Duke of Bedford, he holds out his hat and pleads, “Pray remember your old Manager, burnt-out & lost his little all—not admitted into the new firm on account of his honesty & extreme punctuality in all his dealings—his talents not suiting the present committe [sic] of Taste who instead of Shakespeare, Vanburgh, & Congreve, will give you nothing but the bottom of the Tap Tub. as Mother Cole [in Samuel Foote’s drama _The Minor_] says ‘when we are missed we are mourn’d’ depend on it without my assistance they will be all lost in a storm of their own Brewing” (courtesy of the British Museum)

Just months after the fire, Sheridan applied to the Whig politician Samuel Whitbread (1764-1815; Fig. 15) to head a committee that would manage Drury Lane’s complex debts and to supervise its rebuilding. Together, the two men played a role in preventing a bill from passing in Parliament to establish a third patent theatre in the city of London (Genest 8: 220; Moore Memoirs 2: 372-77), and Whitbread soon became the dominant player in the construction of Drury Lane. His committee raised finances through the formation in 1810 of a joint-stock company, known as The Theatre Royal Drury Lane Company of Proprietors, which planned to raise £300,000 by 3,000 shares of £100 each (Sheppard 35: 21). Though the Company never reached its goal, its members raised enough capital by the autumn of 1811 to begin to address creditors’ claims, to hire the architect Benjamin Dean Wyatt, and to purchase, among other things, Sheridan’s stake in Drury Lane for £40,000, of which £24,000 was to go to Sheridan for his half-share, £12,000 to his son Tom for his quarter-share, and £4,000 for the property of the fruit offices, which managed the sale of fruit and other refreshments in the Theatre’s saloon (35: 22). Whitbread had already asked Sheridan to withdraw from management due to his reputation for financial incompetence. As Whitbread wrote in a 5 November 1811 letter to Sheridan’s son Tom, “It is unquestionably hard and galling that you should be in the sort of proscription there is on the name of Sheridan, as connected with the New Theatre . . . . The Question asked before any Man or Woman will put down their Names [to contribute to a New Theatre fund] is this ‘Has Mr. Sheridan anything to do with it?’ A direct negative suffices” (Price 3: 131n). Sheridan’s relinquishment of his financial stake in the Theatre also signified his full relinquishment of a managerial role.[8] The momentous transaction was caricatured by Charles Williams in Clearing away the Rubbish of Old Drury (Fig. 16), which portrays laborers removing the remains of the fallen Theatre, including piles of bricks and Sheridan himself. In order to begin anew, the image suggests, a broken-down Sheridan and his financial patrimony must be removed along with the rest of the trash. The first stone of the new Theatre was laid on 29 October 1811, and during the summer of 1812, while construction continued apace, the Company of Proprietors obtained a government renewal of the patent. In response, Williams followed up his former print with Act the 2.d of the New Drury Lane Brewery or a Managers Spur to Progress (Fig. 17). Taken together, Williams’s satires depict Whitbread as young, industrious, and successful, and Sheridan, by contrast, as old, fat, and resentful over his expulsion from the Drury Lane management.

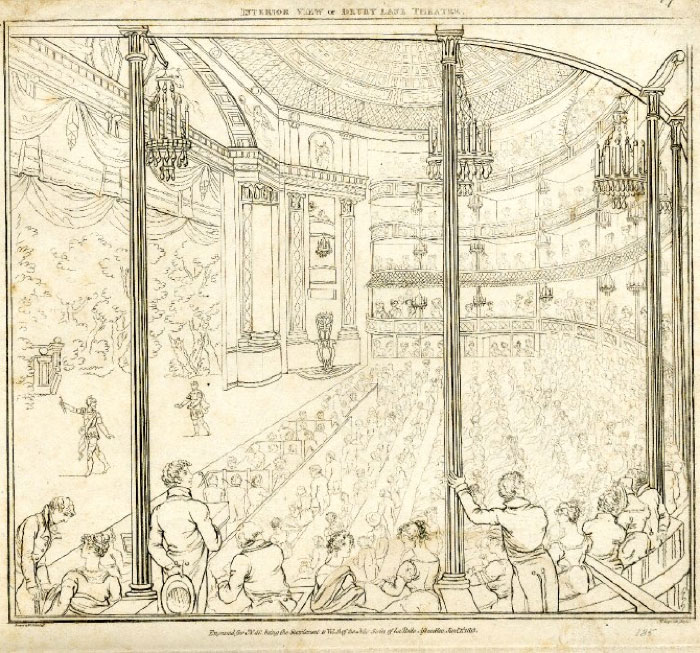

Figure 18: Nicolaus von Heideloff, Interior View of Drury-Lane Theatre (January 1813, courtesy of the British Museum)

Figure 19: Richard Westall, George Gordon Byron, 6th Baron Byron (1813, © National Portrait Gallery, London)

In one dread night our city saw, and sighed,

Bowed to the dust, the Drama’s tower of pride;

In one short hour beheld the blazing fane,

APOLLO sink, and SHAKSPEARE cease to reign.Ye who beheld, oh sight, admired and mourned,

Whose radiance mocked the ruin it adorned!

Through clouds of fire, the massy fragments riven,

LikeIsrael’s pillar, chase the night from heaven,

Saw the long column of revolving flames

Shake its red shadow o’er the startledThames,

While thousands, thronged around the burning dome,

Shrank back appalled, and trembled for their home;

As glared the volumned blaze, and ghastly shone

The skies, with lightnings awful as their own;

Till blackening ashes and the lonely wall

Usurped the Muse’s realm, and marked her fall;

Say—shall this new nor less aspiring pile,

Reared, where once rose the mightiest in our isle,

Know the same favour which the former knew,

A shrine for SHAKSPEARE—worthy him and you?Yes—it shall be—The magic of that name

Defies the scythe of time, the torch of flame,

On the same spot still consecrates the scene,

And bids the Drama be where she hath been:—

This fabric’s birth attests the potent spell,

Indulge our honest pride, and say, How well!

As soars this fane to emulate the last,

Oh! might we draw our omens from the past,

Some hour propitious to our prayers, may boast

Names such as hallow still the dome we lost.

On Drury first your SIDDONS’ thrilling art

O’erwhelmed the gentlest, stormed the sternest heart;

On Drury, GARRICK’S latest laurels grew:

Here your last tears retiring ROSCIUS drew,

Sighed his last thanks, and wept his last adieu.

But still for living wit the wreaths may bloom

That only waste their odours o’er the tomb,

Such Drury claimed and claims,—nor you refuse

One tribute to revive his slumbering muse,

With garlands deck your own MENANDER’S head!

Nor hoard your honours idly for the dead!(Morning Chronicle 12 October 1812)

Reviews came pouring in. Among them, the Morning Chronicle pronounced Byron’s verses “tame” and “neither gracefully nor correctly recited” (12 October 1812). The Times carped, “This Address is throughout of the lowest order for taste, conception, or knowledge of poetic language” (12 October 1812). A week later, however, it softened its tone: “we will certainly allow it to be better than any of the others which we have read; though that is far from making it a good one. . . . Lord Byron’s Address is a very prosaic thing” (“Drury-Lane Address,” 20 October 1812). In response to the poem’s cold reception, Leigh Hunt in The Examiner remarked, “though . . . we cannot consider it as a very favorable specimen of his powers,” “for our own parts, . . . we are rather surprised, on such an occasion, to see a composition so good” (18 October 1812). Byron’s heroic couplets, Hunt suggests, fit the bill for an inauguration that was to be characterized less by celebratory exuberance than by careful restraint. Clearly, the memory of Covent Garden’s opening night three years prior in 1809 was still fresh and, for many, disturbing.

RIOT

And now . . . cast your eyes over my head to what the builder [of the 1812 Drury Lane Theatre] . . . calls the proscenium. No motto, no slang, no popish latin to keep the people in the dark. No Veluti in Speculum. . . . The Covent Garden manager [Kemble] tried that, and a pretty business he made of it! When a man says Veluti in speculum, he is called a man of letters. Very well, and is not a man who cries O.P. a man of letters too? You ran your O.P. against his Veluti in Speculum, and pray which beat?

– W.C. “In the Character of a

Hampshire Farmer,” Rejected Addresses: or the New Theatrum Poetarum, p.21.[10]

On 18 September 1809, after a chorus of the national anthem, John Philip Kemble mounted the stage to give his own poetic Address on the opening of the new Theatre Royal Covent Garden. But as soon as he began to speak, he was greeted by an uproar. It continued, even as he declaimed the final lines:

For this our Fabrick,—banish we, to-night,

Figures worn threadbare, metaphors grown trite.

No Phœnix from her ashes shall arise,—

Stale to our thoughts as sparrows to our eyes;—

No naked Truism be cloak’d anew,

To tell that Fire which cheers, consumes us too;—

No, —let a Briton now to Britons speak;

His cause is strong, although his language weak.

We feel, with glory, all to Britain due,

And British Artists raised this Pile, for you;

To guard the Staple Genius of our Land.

Solid our Building, heavy our expence;

We rest our Claim on your Munificence:—

What Ardour plans a Nation’s Taste to raise,

A Nation’s Liberality repays. (“Theatre, Covent Garden,” Morning Chronicle 19 September 1809)

Kemble’s professed renunciation of figural language in the name of a forthright appeal to nationalist sentiment (“let a Briton now to Britons speak”) fell on deaf ears. Audience members were not in the mood for his performance then or later. The Times reported, “we believe not a single word . . . was heard by the most acute listener in the house: hisses, groans, yells, screeches, barks, coughs, shouts, cries of ‘Off! lower the prices! six shillings! pickpockets! imposition! Cut-purse!’ &c. &c. served to vary, but nothing could add to, the clamour . . . which was always at its highest when Mr. Kemble was there” (19 September 1809). Thomas Tegg, in his long documentary poem The O.P. War (1810), described the scene as follows:

When Kemble entered as Macbeth,

It was in vain he spent his breath,

For not a word could reach the ear:

E’en Mrs. Siddons I cou’dn’t not hear.

. . . . .

What hissing, yelling, howling, groaning!

What barking, braying, hooting, moaning!

The people bellow’d, shouted, storm’d,

The actors in dumb show perform’d.

Those in the pit stood up with rage,

And turn’d their backs upon the stage. (3)

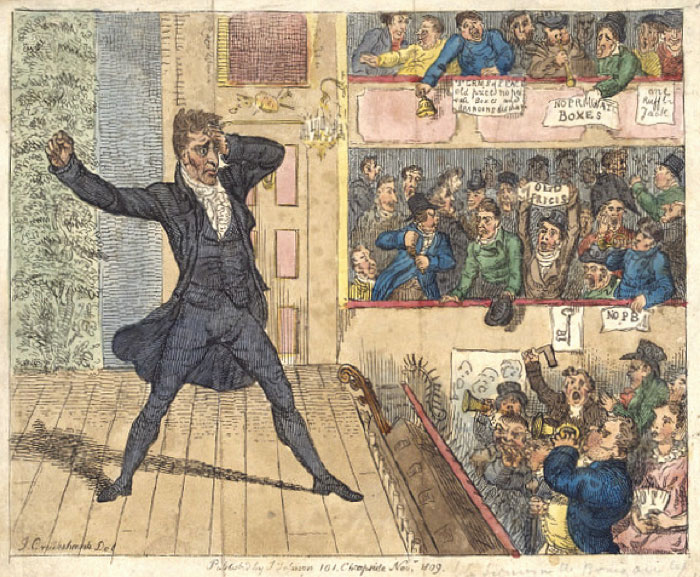

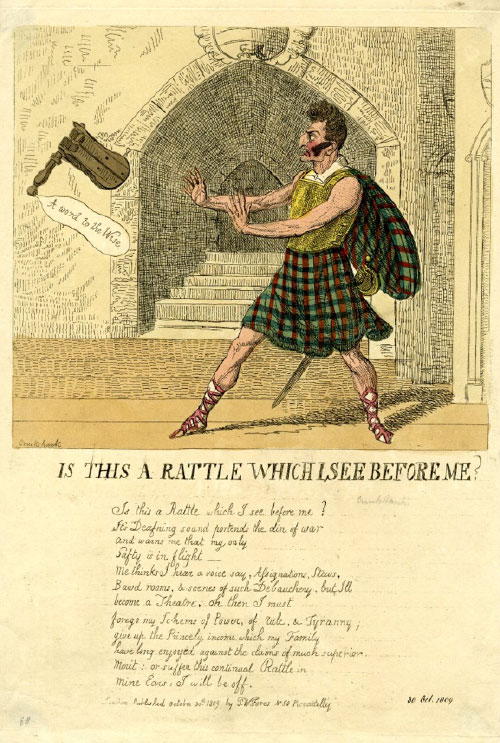

Isaac Cruikshank produced two graphic satires, King John’s First Appearance at the New Theatre, Covent Garden (Fig. 20) and Is This a Rattle Which I See Before Me? (Fig. 21), illustrating Kemble’s on-stage reaction to the events of the evening—the first figuring Kemble as a self-serving King John and the second as a corrupt Macbeth.

Figure 20: Isaac Cruikshank, King John’s First Appearance at the New Theatre, Covent Garden (November 1809). The image renders a baffled and distraught Kemble as King John (c.1166-1216), King of England from 1199-1216 and the villain king of the Robin Hood legends. In addition to losing Normandy and other English territories in France to Philip II of France and being excommunicated after refusing to accept Stephen Langton as the new Archbishop of Canterbury, King John is remembered for inciting civil war. His troubled dealings with the Church and increased taxation of barons (land-owning nobility), among other concerns, provoked retaliation. In 1215, rebel baron leaders marched into London, taking the capital, along with Lincoln, Northampton, and Exeter. At Runnymede, near Windsor, the King succumbed to the barons’ demands when he signed a document, stating that he accepted terms as they were outlined in the Magna Carta, which limited monarchical power and upheld individual rights over the wishes of the sovereign. Though King John later declared his statement invalid and resumed civil war, the Magna Carta became a formative document of English constitutional practice. Here, as in figures 31 and 32, Kemble is figured as an egotistical and incompetent King John, whose will opposes that of his people (© Victoria and Albert Museum, London)

Figure 21: Isaac Cruikshank, Is This a Rattle Which I See Before Me? (30 October 1809). Kemble as Macbeth. The image riffs on the dagger scene in _Macbeth_ in its portrayal of an encounter between Kemble and a floating rattle (noisemaker) labeled, “A word to the Wise.” Kemble, in the first four lines of verse below the image, exclaims, “Is this a Rattle which I see before me? / It’s Deafning sound portends the din of war / And warns me that my only / Safty is in flight—” (courtesy of the British Museum)

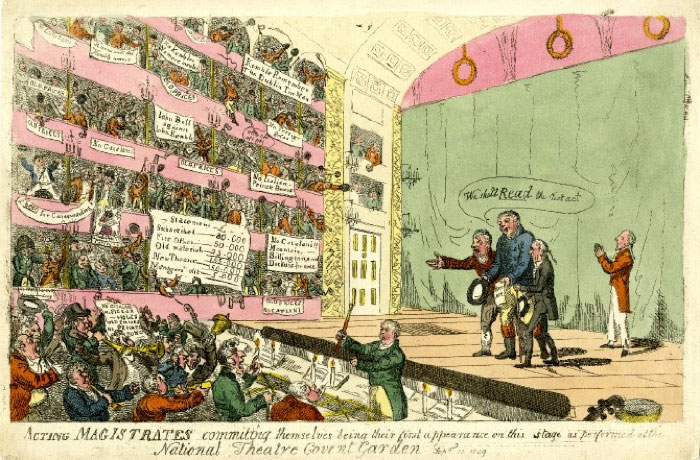

Dismayed and distraught, Kemble summoned the Bow Street police whose station was located just south of the Theatre. After ascending the stage and attempting an unsuccessful plea to playgoers, one of the officers began reading the Riot Act.[11] It was a scene captured by George and Isaac Cruikshank in Acting Magistrates (Fig. 22). The audience retaliated by increasing their noise and shouting, “No Magistrates! No Police in a theatre!”. Recognizing their defeat, the policemen eventually retired.[12] The din subsided, and the fifty or so people remaining in the auditorium at the end of the night broke out in a solemn chorus of God Save the King (The Times 19 September 1809). They then dispersed; their demonstrations, however, were not at an end.

Figure 22: George and Isaac Cruikshank, Acting Magistrates committing themselves being their first appearance on this stage as performed at the National Theatre Covent Garden (18 September 1809). A raucous audience in the pit and boxes (as in figure 20) shout, blow trumpets, ring bells, twirl rattles, and display numerous signs with phrases such as “Old Prices,” “John Bull against John Kemble,” “No Italian Private Boxes,” and a large placard that reads:

Statement — £

Subscribed — 80-000

Fire Office — 50-000

Old Materials — 25-000

155-000

New Theatre — 150-000

Managers of it — 5-000

The numbers suggest that any financial shortfall incurred in the rebuilding of the Theatre (here, £5,000) should be met by the proprietors, not by the theatregoing public. On stage, one of the magistrates threatens, “We shall Read the riot act.” Behind them stands Kemble with his hands pressed together, either in praise of the three men, or in an appeal to the audience, or both (courtesy of the British Museum)

This lively and cacophonous event marked the beginning of the O.P. (Old Price) Riots, a consumer protest movement staged by theatregoers for a total of sixty-seven nights. While some later characterized the O.P.s as an unruly, Jacobinical “mob,”[13] their demonstrations were relatively civil. They were “celebratory as much as recriminatory,” Simon Trussler observes; “There was . . . very little violence, and no damage to property” (208).[14] On the third night, after the conclusion of the inaudible afterpiece, Kemble came forward to attempt to reason with audience members in a speech that The Times paraphrased:

Ladies and gentlemen, I have at last comprehended that the cause of your displeasure consists in the small advance of prices on the Boxes and Pit: . . . One hundred years ago, the Galleries . . . were at the same prices as at present. . . . For the last ten years the Proprietors have not received more than 6 per cent. for their capital, which is certainly very trifling, considering the great hazard of the property. The Proprietors have laid out 150,000l. in building a theatre which should be worthy of a British Public, and in making it the finest Theatre in Europe. . . . I fully rely on your liberality; and, that on mature deliberation, you will not see any thing unreasonable in the proposed regulation of the prices. (21 September 1809)

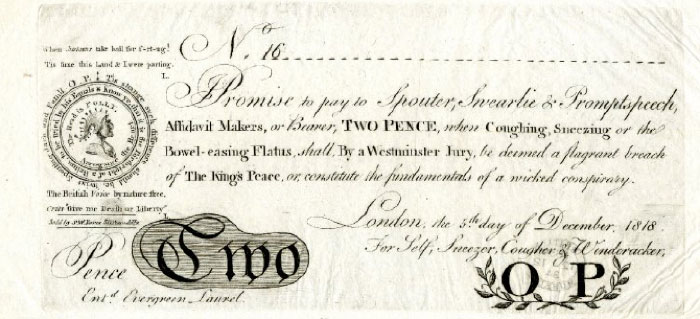

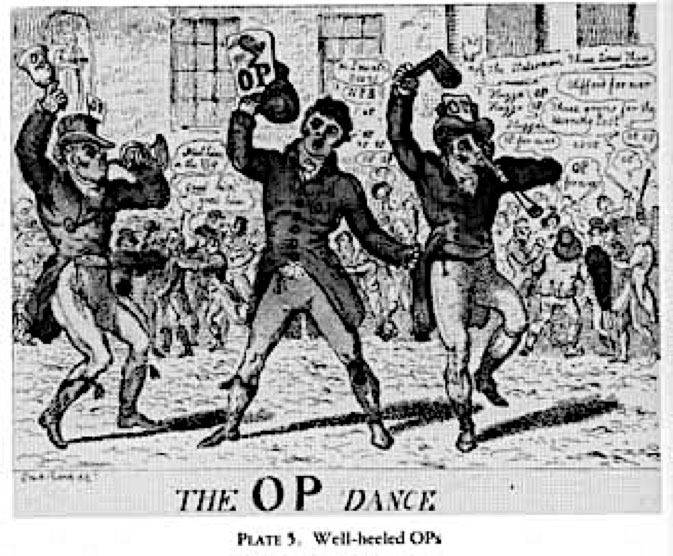

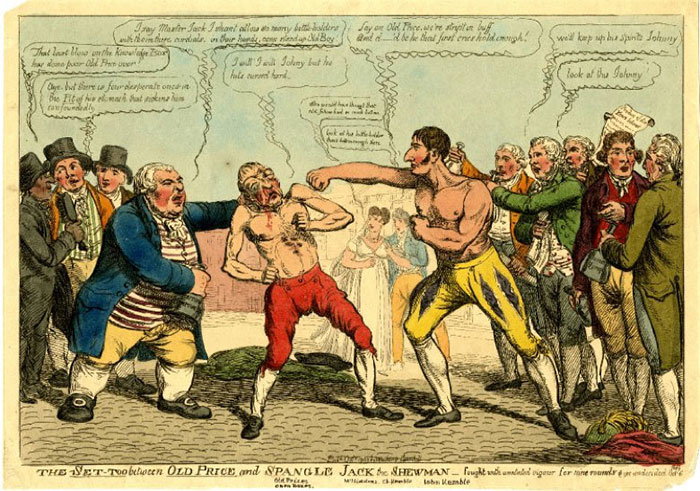

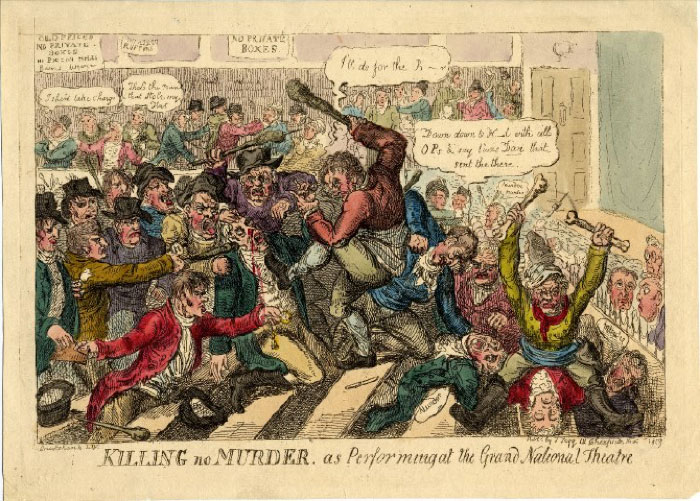

Kemble’s speech, though initially greeted with applause, was ultimately shot down in “vehement disapprobation” (The Times 21 September 1809). The commotion ensued. Day after day, week after week, from September through December, protestors made noise, brandished placards, fashioned O.P. medals (Fig. 23) and faux money (Fig. 24), created signature O.P. songs, and even performed an O.P. Dance (Fig. 25).[15] Hardly relegated to the environs of Covent Garden, the event dominated London’s theatrical and print culture in the form of news reports, pamphlets, broadsides, and graphic images, which circulated throughout the metropolis and beyond. Kemble persisted in his efforts to pacify rioters, through both friendly and forceful means, whether in attempts to reason with them, in a special performance of the beloved clown Joseph Grimaldi, or in the hire of the champion pugilists Daniel Mendoza and Samuel Elias, aka “Dutch Sam,” to extricate troublemakers. Kemble’s reliance on bouncers proved to be a controversial and ultimately damaging tactic, and is addressed in the prints The Set-too between Old Price and Spangle Jack the Shewman (Fig. 26) and Killing no Murder. as Performing at the Grand National Theatre (Fig. 27). In both images, Kemble and his cohort come across as merciless thugs. Their efforts backfired time and again. When, for instance, the Covent Garden box-keeper James Brandon arrested Henry Clifford, a radical barrister and an O.P., Clifford, in turn, had Brandon charged with assault and false imprisonment.

Figure 23: Pewter Old Price Medal (1809). Obverse (left): John Bull rides an ass with the face of Kemble, encircled by the text, “From N. to O. Jack You Must Go. / John Bull’s Advice to You is Go: / ’Tis But a Step from N. to O.” Reverse (right): “O” and “P” appear in the center foreground, behind which is a trumpet, a rattle, and laurel branches. The text reads, “God Save the King. / May our rights and privileges remain unchanged” (courtesy of the British Museum)

Figure 24: Imitation Two Pence Note (5 December 1809). The center text reads, “I Promise to pay to Spouter, Swearlie & Promptspeech, / Affidavit Makers, or Bearer, Two Pence, when Coughing, Sneezing or the / Bowel-easing Flatus, shall, By a Westminster Jury, be deemed a flagrant breach / of the Kings Peace, or, constitute the fundamentals of a wicked conspirary [sic] / London, the 5th day of December, 1818 / For Self, Sneezer, Cougher & Windcracker, / OP. Pence / Two / Entd Evergreen Laurel.” To the left of the text are concentric circles that enclose the profile of Kemble wearing a fool’s cap inscribed: “The Head is Folly / Arrogance the Heart.” The text outside inner circle says, “’Tis strange such difference should be, twixt Spouting Jack and Fam’d O.P.” and “Know ye, that it is the Birthright of a Briton, to be tried by his Equals.” Above: “‘When Justasses take bail for f—rt—ng! / Tis time this Land & I were parting.’ L.” Below: “‘The British Voice by nature free, / Cries “Give me Death or Liberty’ L.” (courtesy of the British Museum)

Figure 25: Isaac Cruikshank, The OP Dance. Plate 5. Well-heeled Ops. Frontispiece, _The O.P. Songster for 1810_ (© The British Library Board, 11798.a.23.[7.])

Figure 26: The Set-too between Old Price and Spangle Jack the Shewman—fought with unabated vigour for nine rounds & yet undecided Oct. 6 1809 (October 1809). A muscular Kemble deals a blow to a weak and badly beaten Old Price, who is supported by the personification of England: John Bull. Amidst the many characters, all of whom have something to say, including Siddons and Charles Kemble in the background, John Bull exclaims, “come stand up Old Boy!” to which Old Price answers, “I will! I will Johnny but he hits cursed hard” (courtesy of the British Museum)

Figure 27: George and Isaac Cruikshank, Killing no Murder. as Performing at the Grand National Theatre (November 1809). Crazed ruffians savagely attack O.P. audience members, including the bleeding and unconscious man near the center of the image; his assailant kicks him in the chest. A fellow bruiser to his right cries, “Down down to H—l with all O.P.’s & say t’was Dan [Mendoza] that sent the there” (courtesy of the British Museum)

In the end, Kemble was unable to quell the tumult. In the prints The O.P. Spectacles (Fig. 28) and The N.P. Spectacles (Fig. 29), George and Isaac Cruikshank capture Kemble’s reaction to Covent Garden’s chaotic and unmanageable state of affairs. In the former, a gape-mouthed Kemble wears large glasses, which are stamped with the letters “O” and “P” and mirror the theatre auditorium. The punning image registers both Kemble’s on-stage perspective as a member of the theatre establishment and his shock as a witness of the shift in focus from players to theatregoers, from the boards to the house. Theatrical spectacle, the print has it, is now located off stage. While there had been theatre riots before, such a transfer of dramatic power from the players (and proprietors) to the playgoers was unprecedented. The antagonism it fostered is even more pronounced in the second image, The N.P. Spectacles, which portrays an active house framed in the demonic gaze of Kemble, whose glasses are rimmed with reminders of his opposing position as an advocate of “New Prices.”

Figure 28 (left): George Cruikshank, The O.P. Spectacles (17 November 1809). The text around the lenses reads, “Old House Old Prices and No Private Boxes” and “Old House Old Prices and No Pigeon Holes” (© Victoria and Albert Museum, London). Figure 29 (right): George and Isaac Cruikshank, The N.P. Spectacles (23 November 1809). The text around both lenses reads, “New House New Prices Private Boxes & Pigeon Holes” (© Victoria and Albert Museum, London)

As mentioned above, Kemble cited the “advance of prices on the Boxes and Pit” as the cause for the fracas, and certainly, the moniker of the riots—“Old Price”—suggests as much. In reality, a number of complaints fueled public opposition. They ranged from increased ticket prices (an additional shilling for the boxes and sixpence for the pit); to the replacement of the third tier with boxes for the elite (the private ante-rooms of which were said to promote immoral behaviors such as prostitution and gambling); to the costly hire of the foreign opera singer Catalini; to the transformation of low-cost, upper-gallery seating into crowded, incommodious “pigeon holes” (Figs. 14 and 30) from which spectators could see only the legs of the actors;[16] to resentment over Kemble’s autocratic, supercilious, and repressive response. The complaints, while many and varied, were allied in that they represented the unapologetic pandering of Kemble and his cohort to the wealthy upper classes—a behavior, rioters felt, that marginalized the general public and degraded English dramatic ideals.

Figure 30: Thomas Rowlandson, Pidgeon Hole. A Convent [sic] Garden contrivance to Coop up the gods (20 February 1811). Cramped, uncomfortable, and overheated conditions afflict the theatregoers occupying one of the “pigeon holes” that dotted the upper gallery of Covent Garden Theatre. The figures of Comedy (top left) and Tragedy (top right) flank the scene (courtesy of the British Museum)

Class divisions had long been mapped out in the eighteenth-century seating arrangements of London’s patent theatres, with professionals (lawyers, merchants, men of letters, and so on) in the pit, the upper classes in the boxes, and the lower orders in the galleries, but as Elaine Hadley has shown, demarcations between these areas became more fluid at the turn of the nineteenth century. Tradesmen, craftsmen, apprentices, and other skilled laborers began sitting to a greater extent in the pit, and the expanding size of the theatres made room for a burgeoning urban populace who packed the galleries. This meant that, even as the city itself was becoming more segregated, in Covent Garden and Drury Lane one could yet find a broad cross section of the London community—from a tallow chandler, to a politician, to a duchess—all gathered together in one space (34-38). Furthermore, the growing representation of middle and lower orders meant that, if only by virtue of sheer numbers, these audience members began conceiving of their patronage as central to the welfare of “National Theatre” —a term that the O.P. Riots, with cries such as “National Theatre: Fair Prices: English Drama: No Catalini,” brought into widespread circulation.[17]

For many attending the new Covent Garden, then, the rise in prices and decrease in desirable seating for those on a budget was tantamount to class segregation and disenfranchisement. One incensed commentator wrote of the privatization of boxes that it ensured “the absolute seclusion of a privileged order from all vulgar contact” (qtd. Hadley 40). Leigh Hunt was also outraged: “the Managers . . . have obeyed a certain aristocratic impulse of their pride, and consulted little but the accommodation of the higher orders. The people felt this immediately”; “a whole circle of the Theatre taken from them to make privacies for the luxurious great, is a novelty so offensive to the national habits . . . that the Managers . . . deserve to suffer still more for their mercenary and obsequious encouragement of pride and profligacy” (The Examiner 24 September 1809, 19 November 1809). According to Hunt, London theatre is not a private enterprise but a national concern, and since “national habits” are formed less by the “luxurious great” than by a respectable English public, patent theatre proprietors must consider the needs of even the low-cost ticket holder.[18] The Morning Chronicle articulated the theatre’s duty to the public this way:

A patent is granted by his Majesty, in right of his prerogative, to secure to his people a rational Entertainment at a reasonable rate . . . The public are, therefore, parties to the management of a theatre under an exclusive grant, and they have a right to examine the grounds upon which the demand of higher prices is made. . . . In the new Theatre a whole tier of boxes is . . . taken from the public, and assigned by lease to individuals. . . . If those who receive an exclusive grant from the King (only as the means of better securing to the public a theatrical entertainment) can thus with impunity lock up one whole tier, they may lock up the whole, and make it altogether a private concern. (19 September 1809)

Because Covent Garden receives a patent to perform spoken-word drama, it is subject less to its own financial interests, this reporter argues, than to the interests of the nation, and it is a nation being defined anew. As Gillian Russell, Marc Baer, and Elaine Hadley have shown, the O.P. Riots did more than expose the divide between high and low; they unified a heterogeneous theatregoing public through ritualized conflict that, in turn, defined the role of the theatregoer in the political landscape. By participating in the riots, audience members “changed [the] social meaning of the English theatre audience” (Baer 54).[19]

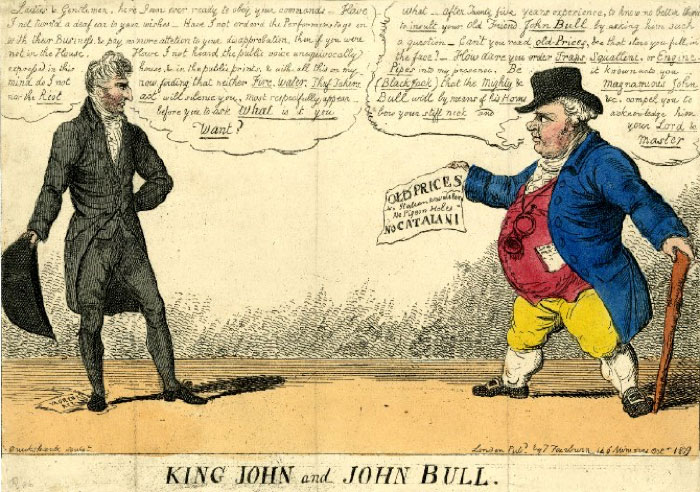

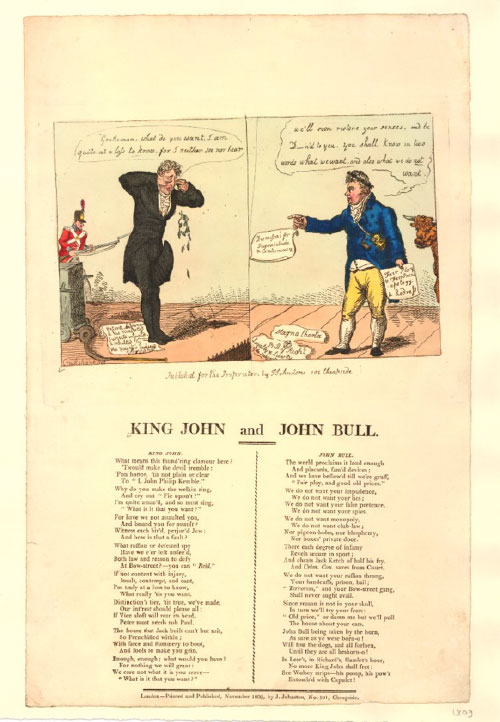

What the O.P. rioters made clear was that the survival of a state-sanctioned National Theatre depended on them. By drawing attention to themselves, they communicated the fact that audience members, whatever their rank, were not merely passive spectators of theatrical events but important players in the theatre—even more so than those who performed on stage. The aim of their ritual disorder was to assert their rights over despotic theatrical governance, and they did so, in the words of Tracy C. Davis, through the “complete abnegation of his [Kemble’s] power to control the market” (20). Isaac Cruikshank’s prints—both entitled King John and John Bull (Figs. 31 and 32)—dramatize these shifting power relations.

Figure 31: Isaac Cruikshank, King John and John Bull (October 1809). The image depicts an intransigent Kemble (left) facing a staunch John Bull (right), who shows Kemble a paper that reads: “OLD PRICES No Italian private Boxes No Pigeon Holes NO CATALANI.” Kemble, under whose left foot is on a paper labeled “Vagrant Act” says, “Ladies & Gentlemen, here I am ever ready to obey your commands—Have I not turn’d a deaf ear to your wishes—Have I not ordered the Performers to go on with their Business, & pay no more attetion to your disapprobation, then if you were not in the House—Have I not heard the public voice unequivocally express’d in this house, & in the public prints, & with all this on my mind do I not now, finding that neither Fire, Water, Theif Takers, nor the Riot act will silence you, Most respectfully appear before you to ask What is it you Want?” John Bull replies, “What—after Twenty five years experience, to know no better than to insult your Old Friend John Bull by asking him such a question—Can’t you read old Prices, &c that stare you full in the face?—How dare you order Traps Squallini [Catalani], or Engine-Pipes into my presence. Be it known unto you (Black Jack) that the Mighty & Magnamious John Bull will by means of his Horns &c, compel you to bow your stiff neck and acknowledge him your Lord & Master.” For information on the character of “King John,” see figure 20 (courtesy of the British Museum)

Figure 32: Isaac Cruikshank, King John and John Bull (November 1809). This broadside ballad, with lyrics below and an image at the top, features a weeping Kemble, tucking his tail between his legs and crying, “Gentlemen, what do you want? I am quite at a loss to know, for I neither see nor hear.” John Bull, who holds a sign saying “Fair Play / & Fair Prices / apology / & Redress” replies, “We’ll soon restore your senses, and be D—-n’d to you. You shall know in two words what we want, and also what we do _not_ want.” For information on the character of “King John,” see figure 20 (courtesy of the British Museum)

In the former, Kemble exclaims, “Ladies & Gentlemen, here I am ever ready to obey your commands—Have I not turn’d a deaf ear to your wishes—Have I not ordered the Performers to go on with their Business, & pay no more attetion [sic] to your disapprobation, then if you were not in the House . . . What is it you Want?” In the latter, two stanzas spoken by John Bull read as follows:

We do not want your impudence,

We do not want your lies;

We do not want your false pretence,

We do not want your spies.

. . . . .

Since reason is not in your skull,

In turn, we’ll try your fears:

“Old price,” or damn me but we’ll pull

The house about your ears.

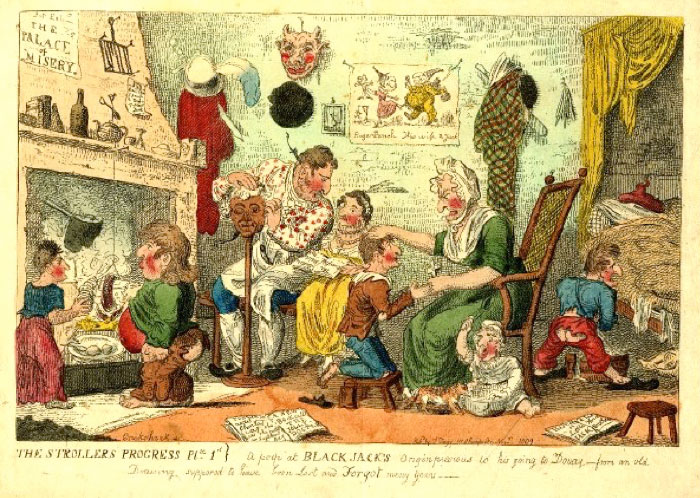

Both images accuse Kemble of feigned ignorance—an offensive pose, suggesting his innocence in the affair and the notion that O.P. complaints were indiscernible, a mere “hubbub wild” (Macready 24). Isaac Cruikshank took Kemble’s “acting” ability to task not only in these images but also in The Strollers Progress Plte 1st} A peep at Black Jack’s origin previous to his going to Douay (Fig. 33), which exposes Kemble’s identity as a French-educated Catholic. In the print, Kemble kneels before his mother who holds a crucifix; the scene takes place just before Kemble is sent to the English Catholic college at Douai, France. Kemble’s humble origins and foreign connections suggest the actor’s present-day hypocrisy in his performance of the English gentleman.

Figure 33: Isaac Cruikshank, The Strollers Progress Plte 1st} A peep at Black Jack’s origin previous to his going to Douay – from an old Drawing supposed to have been Lost and Forgot many years (November 1809). A young John Philip Kemble kneels in front of his mother, his sister Sarah sits behind him with a book on her lap, and their father Roger Kemble speaks to Sarah and dresses a wig. Other siblings (including Stephen and Charles) wear tattered clothing and are variously occupied in an impoverished home environment. The scene reminds viewers of the Kemble family’s lowly beginnings as itinerant players (courtesy of the British Museum)

Prints that reference Kemble’s old-world religion (see also Fig. 13), that make anti-Semitic statements against Mendoza and Elias (“Be Britons still, both true and brave, / And ne’er to Jew or Kemble slave” [Tegg 84]), and that protest against Italian opera and Angelica Catalini, reveal how the class tension, civil unrest, and consumer resistance of the O.P. Riots were underwritten by nativist sentiment. By defining their collective political role in the nation via National Theatre, Covent Garden audience members were also defining what nationhood meant, and this definition was undergirded, first, by a xenophobic repudiation of anything foreign and, second, by a reclamation of what they believed to be true English drama. A statement by one of the O.P. leaders, the radical-turned-Tory Henry Redhead Yorke, provides a case in point: “I am for rebellion; and let me tell King John [Kemble], that if he will not give us the English spirit of Garrick, we will give him and his Frenchified crew, the spirit of Marat. The spirit of Garrick was this, bless his English soul!” (W.D. 447).[20] In these lines, “English sprit” is aligned with David Garrick and stands opposed to the French machinations of John Philip Kemble as King John, a monarch more French than English. John Brewer observes that O.P. references to Garrick and Shakespeare reflect a growing “sense that national theatre should guard a national poet and that public performance of his works was the standard by which the drama should be measured” (422). This notion dovetails with Jacky Bratton’s observation that the concept of National Theatre emerged alongside a new valorization of authorial genius: “Around 1800 the idea of ‘literature’ came to depend upon a[n] aesthetic of autonomy: the artist was envisaged as a unique and self-justified creative spirit” (15). To put it another way, the O.P.’s defense of National Theatre entailed the solidification of an idea of National Theatre—one dependent on identifying literary “greats.” More broadly, it marked an attempt to establish cultural values through a nostalgic appeal to England’s past—a return not just to old prices but to a notion of good old English theatre, exemplified as it was in Garrick’s thespian and managerial legacy, including his promotion of Shakespeare, and in the eighteenth-century patent theatres themselves.

After three months of pandemonium, Kemble and his fellow Covent Garden proprietors succumbed to the rioters’ demands. Kemble had already dismissed Catalani, and on 14 December 1809, he met with his opponents, including the aforementioned Henry Clifford, at the Crown and Anchor pub and agreed to restore the old prices in the pit, reduce the number of private boxes, and drop outstanding legal charges against the rioters. These measures alone, however, were not enough; the next day, on 15 December 1809, the audience demanded a formal apology from Kemble, who then came forward on stage to express his regrets. After he did so, “Mr. Kemble and the other Performers, in the progress of the play, were greeted with applause, and every thing went on most harmoniously. A placard was unfurled in the pit, inscribed with the words, ‘We are satisfied;’ and it was received with expressions of general approbation from all parts of the house” (Morning Post 16 December 1809). While small-scale protests erupted over the course of the evening, Kemble speedily addressed them. By the end of the evening, after sixty-seven nights, the riots had come to a close.

Kemble’s capitulation marked a financial, political, and cultural victory for the O.P.s. The public, acting as a “cultural parliament of the nation” (Moody 67), had triumphed over theatrical despotism. It was an event that resonated for years to come, and, indeed, the 1812 Drury Lane was careful not to repeat the mistakes of its 1809 predecessor. The management did not raise admission prices, keeping them low at three shillings sixpence for a seat in the pit, two shillings for a seat in the lower gallery, one shilling for a seat in the upper gallery, and seven shillings for a box (Morning Chronicle 10 October 1812)—the same as the renegotiated prices at Covent Garden. In order to ensure future stability and prosperity, Whitbread diffused managerial responsibility by establishing a board of directors, with a consulting subcommittee (on which Lord Byron later served from June 1815-April 1816) “empowered to run the theatre as a renewed centre for ‘national’ culture” (Richardson 134).[21] The opening night of 10 October 1812 did not go as well as Whitbread and his fellow proprietors had hoped (due to Byron’s lackluster Address and Elliston’s mediocre performance as Hamlet), but there was no riot (Morning Chronicle 12 October 1812). And although reporters and theatregoers expressed concern over the legitimacy of the Drury Lane competition for Best Address, the staging of Sheridan’s comedy The Rivals (1775) just three days later lifted expectations. Pronounced a “success,” the performance marked the beginning of a new era for the Theatre (Morning Chronicle 16 October 1812).

RESOLUTION

Of late our theatres have been so constructed, that John Bull has been compelled to have very long ears, or none at all; to keep them dangling about his skull like discarded servants, while his eyes were gazing at pieballs and elephants, or else to stretch them out to an asinine length to catch the congenial sound of braying trumpets.

– Preface, Rejected Addresses: or the New Theatrum Poetarum, p.xiii

The fact that the 1812 Drury Lane Theatre management turned to the dramas of Shakespeare and Sheridan for its first week of performances speaks to Sheridan’s early nineteenth-century dramatic status. His bungled management of Drury Lane and his near penury were as yet a subject for caricature,[22] but his plays—all authored in the prior century—were being embraced as masterpieces of English drama, fit for the premiere of a new National Theatre. His works had passed into the annals of theatrical history—even while he was yet alive. As Boaden put it, “One was delighted to see, in the reverse of his fortune, and the decline of his health, the respect that in public loved to wait upon the great orator and still greater wit. . . . Genius awfully whispered as he passed, ‘Remember that he is Sheridan’” (Jordan 2: 229).

If Sheridan’s theatrical glory days were a thing of the past, so were those of the star patent theatre actors, Sarah Siddons, John Philip Kemble, and Dorothy Jordan, upon all of whom the disappointments and stresses of the past years weighed heavily. In 1812, Henry Crabb Robinson recorded in his diary that Siddons’s voice “appeared to have lost its brilliancy (like a beautiful face through a veil)” (45). A month later, he lamented, “Mrs Siddons is not what she was . . . her power of expression [i]s gone” (71). On 29 June 1812, little more than three months prior to the opening of the new Drury Lane, Siddons concluded her stage career in a farewell performance as Lady Macbeth at Covent Garden. Though she continued to give private readings and act in benefits and select productions, she never returned to the stage full time. After his sister’s retirement in 1812, Kemble resigned as manager of Covent Garden and took a two-year leave. He returned to act as Coriolanus at Drury Lane in January 1814 and was met with praise, but just two months later, the twenty-four-year-old Edmund Kean debuted as Shylock at the same theatre. In Leigh Hunt’s pithy phrasing, “Kean appeared and extinguished Kemble” (Dramatic 217). Kemble, suffering as he was from ill health, continued to act over the next few years, sometimes regularly, sometimes sporadically. On 23 June 1817, he performed for the last time at Covent Garden—an event that closed his more than thirty-year career as an actor and manager. Of the actress Dorothy Jordan, Boaden observes, “With the fall of the theatre [Drury Lane] was ascertained [her] retirement” (Jordan 2:229). Jordan’s departure from the stage was delayed, nonetheless, by financial insolvency. She continued to act in an effort to raise money, but circumstances compelled her to give her final performance in the provinces at the Theatre Royal, ![]() Margate in August 1815.

Margate in August 1815.

During the early 1800s, London’s patent theatres witnessed the career dénouements of some of its most prominent figures, and yet these same figures were, like Sheridan, being celebrated as national treasures, remembered for their pinnacle performances in the 1780s and 90s. In the eyes of William Hazlitt, for example, Siddons was “not less than a goddess . . . She was tragedy personified. She was the stateliest ornament of the public mind,” Kemble was “the most excellent actor of his time,” and Jordan was “the child of nature, whose voice was a cordial to the heart . . . whose laugh was to drink nectar . . . and whose singing was like the twang of Cupid’s bow” (272, 297, 49). The nostalgic encomiums produced during this era, whether lauding Garrick’s cultivation of Shakespeare, the comedies of Sheridan, or the performances of London’s acting greats were often, however, more than wistful recollections of times gone by. Deployed in certain contexts, they exemplified a conservative reaction to change—in particular, a resistance to the move from a classical theatre of tragedy and comedy to a modern theatre of spectacle.

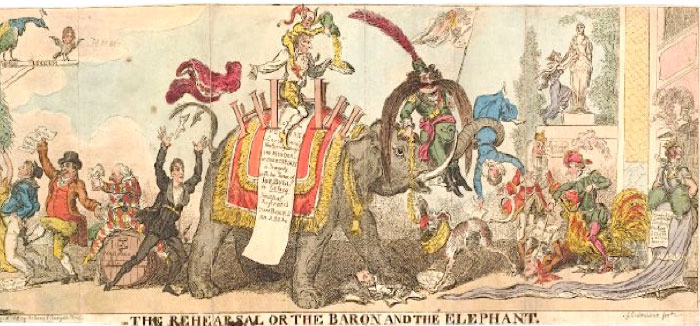

Underlying the O.P. appeal to National Theatre, as indicated above, was an all-out culture war. In addition to mercenary management and foreign opera singers, rioters professed that the degradation of the drama was due, as Jane Moody has revealed, to the mixing of comedy and tragedy and the introduction of spectacular theatrical forms—burletta, melodrama, opera, pantomime, and so on then being performed on “illegitimate” theatre stages—onto the boards of Covent Garden and Drury Lane. “According to one pamphleteer,” Moody writes, “the Covent Garden managers preferred to gratify spectators’ curiosity (and to fill their own coffers) ‘with singing and dancing, with monsters, eunuchs, or any other exotic rarity’ rather than to furnish ‘the food of the mind’ with legitimate drama” (65).[23] Patent theatre stagings of George Colman the Younger’s melodramatic romance Blue-Beard; or Female Curiosity! (Drury Lane, 1798; Covent Garden, 1811) and the pantomime Harlequin and Padmanaba; or, the Golden Fish (Covent Garden, 1811)—the 1811 productions of which featured the famed elephant, Chunee—exemplified such claims and were satirized in George Cruikshank’s The Rehearsal or the Baron and the Elephant (Fig. 34).

Figure 34: George Cruikshank, The Rehearsal or the Baron and the Elephant [detail] (1 January 1812). This print satirizes Covent Garden’s engagement of the elephant, Chunee. In the image, Chunee rampages across a stage and smashes under his left foot several books and a bust of Shakespeare. Riding astride Chunee is John Philip Kemble, upon whose shoulders sits a little person emptying out a bag of money into a tambourine held by Kemble. Draped over the elephant’s saddle is a scroll that reads, “Royal / Menagerie / Covent Garden / This Evening perford / The Murder / of Shakespeare / a Tragedy / with the Farce of / Joh Bull / in Extacy / Principal / Performers / Two Bears / An Ass &c.” Among numerous other figures is Richard Brinsley Sheridan at the left of the image, dressed as Harlequin, sitting atop a cask inscribed “Whitbreds Stale” and extending a mug of “Froth” to Samuel Whitbread, who, in turn, kicks a sailor and holds a paper that says, “A Guinea Pr Week for Native Talent”; with his left hand, he pours coins into a bag, inscribed “Treasury,” held by Sheridan. Sarah Siddons appears on the far right of the image, departing from the stage with bags of money at her waist. A playbill to her left states, “Theatre Royal Covent Garden—Positively the last Season of Mrs Siddon[s]” (courtesy of the British Museum)

Cruikshank’s print reflects the concern that theatrical innovation was arriving at the expense of quality drama; at its center, a scroll reads: “Royal / Menagerie / Covent Garden / This Evening perford / The Murder / of Shakespeare / a Tragedy / with the Farce of / Joh Bull / in Extacy / Principal / Performers / Two Bears / An Ass &c.” Here, Shakespeare, tragedy, and quality acting are sidelined in favor of animal antics and popular allure—a substitution that transforms National Theatre into a farce. Once again, in the middle of it all, riding atop Chunee, is Kemble.

The irony is that Kemble, the day’s consummate Shakespearean tragedian, mounted dramatic spectacles because they drew large audiences. Critics protested, but the public poured in to the theatre nonetheless.[24] Melodramas, burlettas, and pantomimes, with their emphasis on the visual, suited the immense size of Covent Garden and Drury Lane, in that those seated in the back of the auditorium could still follow the action on stage. They also attracted theatregoers through sentiment and song, and, in the case of melodrama, through the experience of what Jeffrey N. Cox terms “sensational realism” (50). The flourishing of these forms was a product, however, of more than practical or aesthetic appeal. Recent historical events—the theatres’ destruction caused by the fires, the displacement of the Drury Lane company, Drury Lane’s managerial crisis, and Covent Garden’s Old Price Riots—made way, paradoxically, not for the resurgence of legitimate theatre but for “the apotheosis of patent illegitimacy” (Moody 69). The financial and cultural disarray of 1808-1812 meant that for four successive theatre seasons, news regarding Covent Garden and Drury Lane had less to do with their dramas than with their disasters. This had the effect of undermining their cultural authority and destabilizing audience-theatre relations. As the non-patents began absorbing audience members, Covent Garden and Drury Lane responded by staging an increasing number of “illegitimate” dramas as a means to ensure their economic viability.[25] Rather than forestall the proliferation of variant theatrical forms, then, the riots encouraged their spread and, as Baer suggests, contributed to a breakdown of the patent theatre monopoly, later secured by the 1843 Theatres Act.[26]

At the same time, the riots—and the broader “decline of the drama” narrative of which they were a part—ensured that such forms would continue to be viewed negatively despite their growing popularity (or even because of it).[27] In the act of championing dichotomies such as high art over low art, spoken word over spectacle, native over foreign, and so on, and in glancing back ruefully into dramatic history, the O.P. protests assisted not only in defining National Theatre but also in memorializing it. By manifesting an ideal vision of English drama that could never be fully recovered, the riots helped cement the cultural and ideological legacy of that elegiac vision—one that would govern critical consciousness for decades to come. In this way, the events of 1808-1812 mark a pivotal time in English theatre. For even as the fires and the O.P. Riots generated a financial situation at Covent Garden and Drury Lane that spurred on their production of new dramatic forms and, in turn, subverted their own claim to legitimacy, the dramatic mourning that accompanied these years, the critical lamentation of a bygone era, meant that National Theatre would come to be understood, as the nineteenth century progressed, no longer in institutional terms (as a synonym for London’s patent theatres) or in terms of its current theatrical productions, but as a metonym for the legendary playwrights, playscripts, and performers of England’s dramatic past.

published March 2016

HOW TO CITE THIS BRANCH ENTRY (MLA format)

Robinson, Terry F. “National Theatre in Transition: The London Patent Theatre Fires of 1808-1809 and the Old Price Riots.” BRANCH: Britain, Representation and Nineteenth-Century History. Ed. Dino Franco Felluga. Extension of Romanticism and Victorianism on the Net. Web. [Here, add your last date of access to BRANCH].

WORKS CITED

Primary Sources

A Genuine Collection of O.P. Songs. London: [1809]. Print.

Ackermann, Rudolph. The Microcosm of London; or, London in Miniature. 3 vols. London: T. Bensley, 1808-10. Print.

Baker, David Erskine, Isaac Reed, and Stephen Jones, eds. Biographia Dramatica: or a Companion to the Playhouse. 3 vols. London: Longman, Hurst, Rees, Orme, and Brown, 1812. Print.

Barrett, Eaton Stannard. The Talents Run Mad: or Eighteen Hundred and Sixteen, A Satirical Poem. London: Henry Colburn, 1816. Literature Online. Web. 23 January 2016.

Boaden, James. The Life of Mrs. Jordan; Including Original Private Correspondence, and Numerous Anecdotes of Her Contemporaries. 2 vols. 2nd ed. London: Edward Bull, 1831. Print.

—. Memoirs of the Life of John Philip Kemble, Esq. Including a History of the Stage, from the Time of Garrick to the Present Period. 2 vols. London: Longman, Hurst, Rees, Orme, Brown, and Green, 1825. Print.

———. Memoirs of Mrs. Inchbald: Including Her Familiar Correspondence with the Most Distinguished Persons of Her Time. 2 vols. London: R. Bentley, 1833. Rpt. Cambridge: Cambridge UP, 2013. Print.

“Burning of Covent-Garden Theatre.” The Times [London, England] 21 September 1808: 3. The Times Digital Archive. Web. 23 January 2016.

Christian, T. P. The Nuptials: A Musical Drama. London: T. Hookham and J. Carpenter, 1791. Eighteenth-Century Collections Online. Web. 23 January 2016.

“Coroner’s Inquest.” The Times [London, England] 22 September 1808: 3. The Times Digital Archive. Web. 23 January 2016.

“Covent Garden Theatre.” The Times [London, England] 19 September 1809: 3. The Times Digital Archive. Web. 23 January 2016.

“Covent Garden Theatre. The Times [London, England] 21 September 1809: 3. The Times Digital Archive. Web. 23 January 2016.

“Covent Garden Theatre. Its Opening.” Morning Post [London, England] 19 September 1809: 3. 19th Century British Newspapers. Web. 23 January 2016.

Daniel, George, and Thomas Dolby, eds. Cumberland’s British Theatre: With Remarks, Biographical and Critical. Vol. 4. London: John Cumberland, 1823-1831. 1-64. Google Books. Web. 23 January 2016.

“Destruction of Drury-Lane Theatre.” The Times [London, England] 25 February 1809: 4. The Times Digital Archive. Web. 23 January 2016.

“Destruction of Drury-Lane Theatre.” The Examiner [London, England] 26 February 1809: 143. 19th Century British Newspapers. Web. 23 January 2016.

“Dreadful Fire. Destruction of Covent-Garden Theatre.” Morning Chronicle [London, England] 21 September 1808: 3. 19th Century British Newspapers. Web. 23 January 2016.

“Drury-Lane Address.” The Times [London, England] 20 October 1812: 3. The Times Digital Archive. Web. 23 January 2016.

“Drury-Lane Theatre Destroyed by Fire.” Morning Post [London, England] 25 February 1809: 3. 19th Century British Newspapers. Web. 23 January 2016.

“Drury-Lane Theatre.” Morning Chronicle [London, England] 27 February 1809: 3. 19th Century British Newspapers. Web. 23 January 2016.

“Drury-Lane Theatre.” The Times [London, England] 12 October 1812: 3. The Times Digital Archive. Web. 23 January 2016.

“Farther Particulars of the Fire at Drury Lane.” The Times [London, England] 27 February 1809: 3. The Times Digital Archive. Web. 23 January 2016.

Genest, John. Some Account of the English Stage, From the Restoration in 1660 to 1830. 10 vols. Bath: Printed by H.E. Carrington, 1832. Print.

Gilliland, Thomas. A Dramatic Synopsis, Containing and Essay on the Political and Moral Use of the Theatre. London: Printed for Lackington, Allen, and Co., 1804. Print.

Goldsmith, Oliver. “Of the Stage.” An Enquiry into the Present State of Polite Learning in Europe. Collected Works of Oliver Goldsmith. Vol. 1. Ed. Arthur Friedman. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1966. 322-330. Print.

Hazlitt, William. Criticisms and Dramatic Essays of the English Stage. Ed. William Hazlitt. 2nd ed. London: G. Routledge and Co., 1854. Print.

Hunt, Leigh. Dramatic Essays. Ed. and Intro. William Archer and Robert W. Lowe. London: Walter Scott, Ltd., 1894. Google Books. Web. 23 January 2016.

Hunt, Leigh. “Theatrical Examiner.” The Examiner 24 September 1809. Rpt. in The Selected Writings of Leigh Hunt, Vol. 1: Periodical Essays, 1805-1814. Ed. Greg Kucich and Jeffrey N. Cox. London, England: Pickering & Chatto, 2003. 108-111. Print.

Hunt, Leigh. “Theatrical Examiner.” The Examiner [London, England] 19 November 1809: 744-745. 19th Century British Newspapers. Web. 23 January 2016.

Hunt, Leigh. “Theatrical Examiner.” The Examiner 18 October 1812. Rpt. in The Selected Writings of Leigh Hunt, Vol. 1: Periodical Essays, 1805-1814. Ed. Greg Kucich and Jeffrey N. Cox. London: Pickering & Chatto, 2003. 257-261. Print.

Macready, William Charles. Macready’s Reminiscences, Selections from His Diaries and Letters. Ed. Frederick Pollock. New York: Macmillan, 1875. Print.

“The Mirror of Fashion.” Morning Chronicle [London, England] 7 November 1808: 2. 19th Century British Newspapers. Web. 23 January 2016.

“The Mirror of Fashion.” Morning Chronicle [London, England] 14 September 1809: 3. 19th Century British Newspapers. Web. 23 January 2016.

“The Mirror of Fashion.” Morning Chronicle [London, England] 12 October 1812: 3. 19th Century British Newspapers. Web. 23 January 2016.

“The Mirror of Fashion.” Morning Chronicle [London, England] 16 October 1812: 3. 19th Century British Newspapers. Web. 23 January 2016.

Moore, Thomas. The Life of Lord Byron. London: John Murray, 1844. Print.

Moore, Thomas. Memoirs of the Life of the Right Honorable Richard Brinsley Sheridan. 2 vols. 3rd ed. London: Longman, Hurst, Rees, Orme, Brown, and Green, 1825. Print.

Petroniculus. “To the Editor.” The Times [London, England] 20 October 1812: 3. The Times Digital Archive. Web. 23 January 2016.

“Placards, at Covent-Garden Theatre, On Saturday, the 23d September.” Morning Chronicle 26 September 1809: 3. 19th Century British Newspapers. Web. 23 January 2016.

Price, Cecil, ed. The Letters of Richard Brinsley Sheridan. 3 vols. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1966. Print.

The Rebellion: or All in the Wrong; A Serio-Comic Hurly Burly. London: Vernor, Hood, and Sharpe, 1809. Print.

Remarks on the Cause of the Dispute between the Public and the Managers of the Theatre Royal, Covent Garden, With a Circumstantial Account of the Week’s Performances, and the Uproar, by John Bull. London: J. Fairburn, 1809. Print.

Robinson, Henry Crabb. The London Theatre 1811-1866. Ed. Eluned Brown. London: The Society for Theatre Research, 1966. Print.

Siddons, Sarah. Letter to Lady Perceval (c. September 1808). Philbrick Library of Dramatic Arts and Theatre History, Autograph letters box 18, folder 11. 4 pp. Honnold Mudd Library, Special Collections, Claremont Colleges.

Smith, Horace, and James Smith. Rejected Addresses: or the New Theatrum Poetarum. London: John Miller, 1812. Print.

Tegg, Thomas. The Rise, Progress, and Termination of the O.P. War, in Poetic Epistles, or Hudibrastic Letters from Ap Simpkins in Town, to His Friend Ap Davies in Wales; Including All the Best Songs, Placards, Toasts, &c. &c. London: Published by Thomas Tegg, 1810. Print.

“Theatre.” Morning Chronicle [London, England] 27 September 1808: 3. 19th Century British Newspapers. Web. 23 January 2016.

“Theatre, Covent Garden.” Morning Chronicle [London, England] 19 September 1809: 3. 19th Century British Newspapers. Web. 23 January 2016.

“Theatre Royal, Drury-Lane. Morning Chronicle [London, England] 10 October 1812: 3. 19th Century British Newspapers. Web. 23 January 2016.

“The Theatres.” The Morning Post [London, England] 16 December 1809: 3. 19th Century British Newspapers. Web. 23 January 2016.

Verax. “To the Editor of the Morning Chronicle.” Morning Chronicle [London, England] 19 October 1812: 3. 19th Century British Newspapers. Web. 23 January 2016.

W.D. “The O.P. Riots.” The Knickerbocker: Or, New-York Monthly Magazine. 29.5 (May 1847): 445a-452. ProQuest. Web. 23 January 2016.

Secondary Sources

Baer, Marc. Theatre and Disorder in Late Georgian London. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1992. Print.

Bratton, Jacky. New Readings in Theatre History. Cambridge: Cambridge UP, 2003. Print.

Brewer, John. The Pleasures of the Imagination: English Culture in the Eighteenth Century. New York: Farrar, Straus, and Giroux, 1997. Print.