Abstract

Released by Chapman and Hall on 15 November 1856, Elizabeth Barrett Browning’s Aurora Leigh—a verse-novel and modern epic—set off literary, social, and political reverberations in Britain, North America, and Europe up to the end of the century. “The advent of ‘Aurora Leigh’ can never be forgotten by any lover of poetry who was old enough at the time to read it,” Algernon Charles Swinburne recalled in 1898. By 1900, Aurora Leigh—among much else the first extended poetical portrait of the professional woman writer in English literature—had appeared in more than twenty editions in England and as many in America. Given its innovative, generically mixed form and its controversial contemporary subject matter, it figured in debates over poetry and poetics, the nature of the realist novel, class divisions and social reform, women’s rights, religion, and the politics of nations. Contrary to the critical legend that Aurora Leigh was greeted by an “avalanche of negative reviews,” responses to it were diverse, shaped by periodical competition and differing print-culture, artistic, political, national and religious contexts. This essay surveys seldom-cited notices in the transatlantic daily and weekly press, analyzes critical debates on Aurora Leigh in the major British periodicals, and charts differing patterns in its American and European as compared to its British reception in the years immediately following its publication. It also indicates at points how debates over Aurora Leigh were intertwined with debates in the visual arts associated with the paintings of J. M. W. Turner and the Pre-Raphaelites.

[1]

i. Introduction and Editions (Nineteenth-Century and Modern)

ii. Setting the Stage: EBB’s International Fame Prior to Aurora Leigh

iii. “Hot and Hot” Controversies, Writers’ Circles, and Critical Myths

iv. The Reception of Aurora Leigh in the Transatlantic Daily and Weekly Press

v. British Periodical Debates: Gender, Class and the Politics of Form

vi. Romney and Socialism, Marian and the “Wrongs of Woman”

vii. The Politics of Nations and European Response

viii. American Reviews and Religious Debates in Britain and the US

ix. Postscript: Obituary and Retrospective Essays in the 1860s

Abbreviations for Frequently Used Materials:

BC—The Brownings’ Correspondence, ed. Philip Kelley, Ronald Hudson, Scott Lewis, et al. 21 vols. (Winfield: Wedgestone P, 1984 – )

LTA—The Letters of Elizabeth Barrett Browning to Her Sister Arabella, ed. Scott Lewis. 2 vols. (Waco: Wedgestone P, 2002)

WEBB—The Works of Elizabeth Barrett Browning, Gen. Ed. Sandra Donaldson. Vol. Eds.: Sandra Donaldson, Rita Patteson, Marjorie Stone, and Beverly Taylor. 5 vols. (London: Pickering and Chatto, 2010)

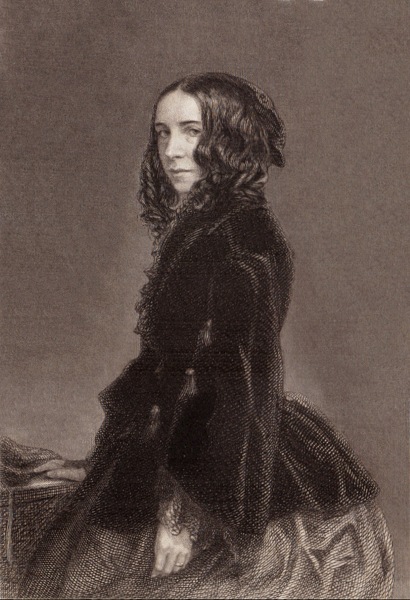

Figure 1: An 1871 engraving of an 1859 photograph of Elizabeth Barrett Browning (photograph by Macaire Havre, engraving by T. O. Barlow)

i. Introduction and Editions (Nineteenth-Century and Modern)

Elizabeth Barrett Browning’s Aurora Leigh, the work she described in its “Dedication” as expressing her “highest convictions upon Life and Art,” was released by her London publisher, Chapman and Hall, on 15 November 1856 (though dated “1857”). Simultaneously, it appeared from C. S. Francis across the Atlantic in ![]() New York. In her letters, EBB variously described Aurora Leigh as a “poem of a new class,” a “romance-poem,” and a “poetic art-novel” (qtd. Stone, “Critical Introduction” WEBB, 3: vii). Charles Hamilton Aidé in the Edinburgh Weekly Review noted it had been greeted as both a “‘modern epic’” and a “‘three-volume novel’” (7), describing it in a private letter as “the Poem of the Age” (Meredith 132). W. J. Fox similarly termed it the “Book of the Age,” while for John Ruskin, it was the “first. . . perfect poetical expression of the Age” (qtd. LTA 2: 326n5, 277n4). EBB was amused to hear that in

New York. In her letters, EBB variously described Aurora Leigh as a “poem of a new class,” a “romance-poem,” and a “poetic art-novel” (qtd. Stone, “Critical Introduction” WEBB, 3: vii). Charles Hamilton Aidé in the Edinburgh Weekly Review noted it had been greeted as both a “‘modern epic’” and a “‘three-volume novel’” (7), describing it in a private letter as “the Poem of the Age” (Meredith 132). W. J. Fox similarly termed it the “Book of the Age,” while for John Ruskin, it was the “first. . . perfect poetical expression of the Age” (qtd. LTA 2: 326n5, 277n4). EBB was amused to hear that in ![]() America, as in England and

America, as in England and ![]() Florence, it was sometimes identified as “Mrs. Browning’s gospel,” remarking on the term to her sister Arabella, “Is it entirely prophane, or simply ridiculous?” (LTA 2: 275). After selling out in a fortnight (LTA 2: 273), Aurora Leigh appeared in a fifth edition by EBB’s death in 1861, although only the fourth incorporated new revisions by EBB (Donaldson, “Textual Introduction” WEBB, 3: xxxiii-iv). By 1887, Aurora Leigh was in a “twentieth” English edition (Barnes 121); from 1861 to 1900, it was reprinted at least twenty-one times in the US, with eight reprints from James Miller of New York in the 1860s alone (Barnes 121, 110-13). Moreover, a “new American edition” could “sell ten thousand copies” (Reynolds, 1992 149).

Florence, it was sometimes identified as “Mrs. Browning’s gospel,” remarking on the term to her sister Arabella, “Is it entirely prophane, or simply ridiculous?” (LTA 2: 275). After selling out in a fortnight (LTA 2: 273), Aurora Leigh appeared in a fifth edition by EBB’s death in 1861, although only the fourth incorporated new revisions by EBB (Donaldson, “Textual Introduction” WEBB, 3: xxxiii-iv). By 1887, Aurora Leigh was in a “twentieth” English edition (Barnes 121); from 1861 to 1900, it was reprinted at least twenty-one times in the US, with eight reprints from James Miller of New York in the 1860s alone (Barnes 121, 110-13). Moreover, a “new American edition” could “sell ten thousand copies” (Reynolds, 1992 149).

In 1898, in his “Prefatory Note” to yet another “new” edition of the novel-epic that had so engaged its “Age,” Algernon Charles Swinburne remarked:

The advent of “Aurora Leigh” can never be forgotten by any lover of poetry who was old enough at the time to read it. Of one thing they may all be sure — they were right in the impression that they never had read, and never would read anything in any way comparable with that unique work of audaciously feminine and ambitiously impulsive genius. It is one of the longest poems in the world and there is not a dead line in it. (ix)

Swinburne’s letters attest to the immediate impact of Aurora Leigh in 1856 that he was recalling forty years later (see below). As the examples of Swinburne, Ruskin, Fox, and Aidé among multiple others suggest, men as well as women saw the publication of Aurora Leigh as a key event—or, at the very least, regarded it as a controversial work of the times. Its impact on Emily Dickinson, who saluted Elizabeth Barrett Browning’s poetry as “Titanic opera” in one of three tribute-elegies to “that Foreign Lady,” was profound.[1] In ![]() Italy, Aurora Leigh was greeted as a “‘Revelation’” by the expatriate network of English, Scottish, and American women writers and artists surrounding EBB in Florence and

Italy, Aurora Leigh was greeted as a “‘Revelation’” by the expatriate network of English, Scottish, and American women writers and artists surrounding EBB in Florence and ![]() Rome (Chapman, “Poetry, Network, Nation” 277). These Anglo-Italian networks explain the New York publisher James Miller’s production of a “Florence Edition” in 1870 (Barnes 113). In

Rome (Chapman, “Poetry, Network, Nation” 277). These Anglo-Italian networks explain the New York publisher James Miller’s production of a “Florence Edition” in 1870 (Barnes 113). In ![]() France, leading critics such as Émile Montégut and Hippolyte Taine analyzed the poem in relation to modern English life and letters (see below).

France, leading critics such as Émile Montégut and Hippolyte Taine analyzed the poem in relation to modern English life and letters (see below).

In the first seventy years of the twentieth century, Aurora Leigh—along with most of the other works that made EBB the most internationally recognized English woman poet of the nineteenth century—was largely erased from literary history, and she was chiefly identified as the author of Sonnets from the Portuguese. In effect, “Mrs. Browning” was consigned to the “basement” in “the mansion of literature” to eat “vast handfuls of peas on the point of her knife,” as Virginia Woolf sardonically observed in 1931 (134). Modern critics have variously traced EBB’s transformation into a “lost saint,” the “handmaid” to Robert Browning’s genius, and the “madwoman in the basement.”[2] A sense of both how much was lost and of the critical attention EBB’s writings once again command can be gleaned from Donaldson’s annotated bibliography of criticism on EBB’s works from 1826 to 1990 (running to over 600 pages); from essays in the Dictionary of Literary Biography, the new Dictionary of National Biography, and the Wiley-Blackwell Encyclopedia of Victorian Literature; and from the survey of EBB’s life and works in the “Introduction” to the Broadview selected edition of her poetry.[3]

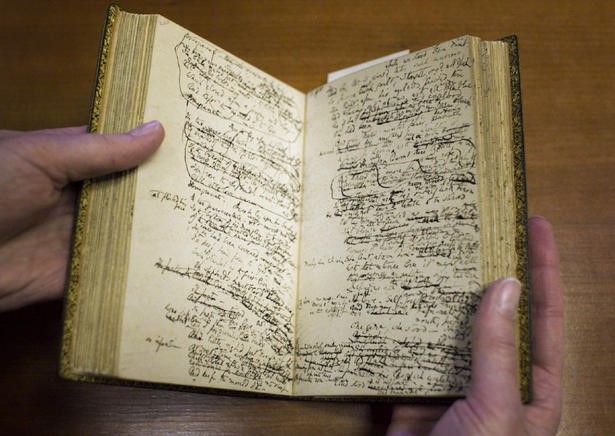

In the case of Aurora Leigh, Cora Kaplan’s 1978 Women’s Press edition was pivotal in recovering EBB’s “Poem of the Age” for modern readers, with an “Introduction” brilliantly elucidating the intertextuality created by EBB’s engagement with a wide range of mid-Victorian texts, authors, and issues. But Kaplan gave little attention to the composition of Aurora Leigh, and even less to establishing a definitive text: work first done by Margaret Reynolds in her award-winning 1992 Ohio University Press scholarly edition of the verse-novel, containing much information on its manuscripts (see Fig. 2), texts, and contexts that could not be included in her Norton Critical Edition (1996). Reynolds’ work, remedying the defects of other editions of Aurora Leigh at the time,[4] is foundational for the Aurora Leigh volume in the 2010 Pickering and Chatto Works of Elizabeth Barrett Browning, edited by an international team of scholars.[5] The “Critical Introduction,” “Textual Introduction,” and annotations in WEBB incorporate information from EBB’s correspondence and scholarship appearing since the early 1990s: especially in the invaluable, progressively appearing volumes of The Brownings’ Correspondence, edited by Philip Kelley and co-editors.[6] Scott Lewis’s edition of EBB’s letters to her sister Arabella also provides much information on the contexts and reception of Aurora Leigh, as does Florentine Friends, Kelley and Donaldson’s edition of the Brownings’ letter to their intimate friend Isa Blagden.

This BRANCH essay seeks to provide a more comprehensive, transnational analysis of the periodical response to Aurora Leigh than is currently available in these and other editions of EBB’s poetry or in critical studies—including the “Overview” of Victorian and modern criticism at www.ebbarchive.org, written as a “digital annex” for my “Critical Introduction” to Aurora Leigh in WEBB.[7] In much of the modern criticism, recycled selective quotations from a limited number of more conservative British periodicals such as Blackwood’s and the Edinburgh Review have perpetuated the skewed and historically inaccurate assumption that critics were almost unanimous in denouncing Aurora Leigh. While I offer a detailed analysis of the reviews in influential British periodicals in section five, I approach them contextually, in relation to each other and to overlooked assessments in seldom-cited quarterlies, monthlies and literary magazines, as well as in light of notices in the transatlantic daily and weekly press. These materials not only illumine the animated, multi-sided debates that Aurora Leigh provoked, indicating “why poetry matters to periodical studies,” as Linda K. Hughes argues in a widely influential article (Hughes, “Wellesley” 2007). The diverse responses to Aurora Leigh also underscore the political, literary, religious, and national affiliations informing reviewers’ approaches and highlight the intense competition among periodicals at mid-century, as new, cheaper weeklies competed with more established quarterlies (Huett 64-5). Given the range of controversial issues EBB’s “poem of a new class” engaged, the reviews thus open a window on the periodical print culture that supplies such a fascinating record of nineteenth-century developments in the arts, society, politics, religion, and the sciences.

ii. Setting the Stage: EBB’s International Fame Prior to Aurora Leigh

In part, the publication of Aurora Leigh in 1856 was perceived as an “advent” because of EBB’s reputation as England’s most internationally recognized woman poet at the time. Her 1838 volume, The Seraphim, And Other Poems, following on ballads published in annuals and periodicals, had identified her as a promising poet of “Genius and attainments” in the eyes of William Wordsworth, among others (BC 4:347). By 1842, Alfred Tennyson and the publisher of his 1842 Poems, Edward Moxon, were also expressing keen interest in her poetry (BC 7:4, Stone, 1995 29). It was her 1844 collection, however—published in England by Moxon as Poems and in America by Henry G. Langley as A Drama of Exile: With Other Poems—that first established her transatlantic fame as “Elizabeth Barrett Barrett.” The two-volume collection was widely reviewed on both sides of the Atlantic, as evinced by reprints of all known reviews of the Brownings’ poetry in the “Appendices” of The Brownings’ Correspondence. George William Curtis recalled in Harper’s Magazine in 1861 that EBB’s 1844 volumes “had a more general and hearty welcome in the United States than [those by] any English poet since the time of Byron and Company” (555).[8]

Like the later reviews of Aurora Leigh, the reviews of EBB’s 1844 Poems record vigorous debates, incorporating both praise and animated criticism. Among much else, EBB’s position as a transatlantic literary celebrity prompted Edgar Allan Poe’s dedication of The Raven and Other Poems (1845) to “Miss Elizabeth Barrett Barrett,” the “Noblest of Her Sex.” Despite this effusive dedication, Poe’s actual review of the “constatellatory radiance” of EBB’s 1844 collection, “surpass[ing] all of her poetical contemporaries of either sex” with “a single exception” (evidently Tennyson), alternates between rhapsodic praise of the “beauties” of EBB’s poems and condemnation of their “inadmissible rhymes” and “deficiencies in rhythm” (BC 10: 355-6). EBB, for her part, remarked that “Mr. Poe seems to me in a great mist on the subject of metre” and defended the precedents for her experimental rhymes (influencing Dickinson’s later iconoclastic rhyming). She nevertheless was pleased with his dedication to her, quipping to her cousin John Kenyon, “what is to be said when a man calls you the [‘]‘noblest of your sex’ . . . ‘Sir, you are the most discerning of yours.’!” (BC 10: 208, 12 164-5).

With the publication of her expanded 1850 Poems, EBB’s international reputation was further extended: now as “Elizabeth Barrett Browning” or “Mrs. Browning” (although she never used the latter as an authorial name in signing her manuscripts or in publishing, and the anachronistic “Barrett Browning” employed by modern critics was chiefly applied to her son in the Nineteenth Century).[9] Her 1850 collection included selected works from her 1838 collection (often in intensively revised form), all of her 1844 poems (also in some cases revised), and numerous new works: most notably Sonnets from the Portuguese and her much admired 1850 translation of Aeschylus’s Prometheus Bound. Poems (1850) was reviewed not only in England, ![]() Ireland,

Ireland, ![]() Scotland, and America, but also in France, where Joseph Milsand discussed it together with EBB’s first major poem on the “Italian question”—Casa Guidi Windows (1851)—in the influential Continental Revue des Deux Mondes in 1852 (LTA 1:424n15). Some of the first tribute poems to EBB—from Dinah Maria Mulock Craik and Bessie Rayner Parkes in England and from Helen Whitman in America—appeared in response to her 1850 collection.[10]

Scotland, and America, but also in France, where Joseph Milsand discussed it together with EBB’s first major poem on the “Italian question”—Casa Guidi Windows (1851)—in the influential Continental Revue des Deux Mondes in 1852 (LTA 1:424n15). Some of the first tribute poems to EBB—from Dinah Maria Mulock Craik and Bessie Rayner Parkes in England and from Helen Whitman in America—appeared in response to her 1850 collection.[10]

Demand led to a new, third, English edition of Poems in 1853; this time, EBB made relatively few changes apart from a new opening for the 1844 lyrical drama, “A Drama of Exile.” In the meantime, pirated “new” editions by C. S. Francis were proliferating in America. Dickinson had access to a C. S. Francis pirated edition published in 1852, acquired by her future sister-in-law Susan Gilbert in January, 1853.[11] Given the absence of any effective international copyright law, EBB received “nothing!,” as she noted, for these editions, despite Francis’s reported remarks that “he had intended to pay Mrs. Browning as if she were an American author” (BC 17: 173). The pirated editions did, however, fuel her growing popularity, as they did in the case of Charles Dickens’s novels and Tennyson’s poetry. When Dickinson’s later mentor, Thomas Wentworth Higginson, wrote to Robert Browning on 4 January 1854 to express his admiration for the English poet’s little appreciated Sordello, he commented that “Mrs. Browning’s poems are household words in ![]() Massachusetts to every school boy & (yet more) every school girl” (BC 20: 53). In England in the same period, the profile of her 1850 and 1853 collections is suggested by Elizabeth Gaskell’s use of four chapter epitaphs from these poems for North and South (1854-55)[12]—a pattern she would later follow in taking her epigraph for The Life of Charlotte Brontë (1857) from Aurora Leigh (V. 434-41).

Massachusetts to every school boy & (yet more) every school girl” (BC 20: 53). In England in the same period, the profile of her 1850 and 1853 collections is suggested by Elizabeth Gaskell’s use of four chapter epitaphs from these poems for North and South (1854-55)[12]—a pattern she would later follow in taking her epigraph for The Life of Charlotte Brontë (1857) from Aurora Leigh (V. 434-41).

A fourth new English edition of Poems was released by EBB’s savvy publisher Chapman and Hall on 1 November 1856, this time in three volumes including Casa Guidi Windows among other new works and incorporating additional revisions by the author in the texts of various poems. This fourth edition of Poems—the last published in EBB’s lifetime (and therefore the copytext for Volumes I and II of the 2010 Works)—set the stage for the publication of Aurora Leigh two weeks later. In America, C. S. Francis now offered to pay EBB a “hundred pounds” for exclusive American rights to the work and advance copy of the poem (LTA 2: 281, 283n20) —a sign of the expectations it generated across the Atlantic. Browning was eventually successful in negotiating an agreement with Francis for this amount to bring out Aurora Leigh simultaneously with its English publication, and a parallel agreement with James T. Fields to publish Men and Women in America for £60 (BC 20: 229n6, 23).

iii. “Hot and Hot” Controversies, Writers’ Circles, and Critical Myths

Apart from EBB’s international fame in 1856, another reason why the publication of Aurora Leigh constituted an “event” was clearly its intense topicality: what EBB termed its engagement with “‘hot and hot’” issues “from the times” (BC 21: 111). She simultaneously addresses artistic debates and what Victorians termed the “woman question” through her portrait of Aurora’s education, apprenticeship, career, and poetic philosophy, employing a dramatic, first-person perspective in a narrative opening with words identifying Aurora as a mature and committed woman writer: the author of “many books” for “others’ uses” who now “will write” her own story for her “better self” (I. 1-4). Through Aurora’s relationship with her cousin, the philanthropic reformer Romney Leigh, Aurora Leigh also engages with what Victorians termed the “social question,” the set of issues so central to “condition of England” novels of the period such as Elizabeth Gaskell’s Mary Barton and North and South and Charles Dickens’s Hard Times. Inspired by French socialist theorists such as Charles Fourier, Romney seeks to recruit the young, orphaned Aurora as a “handmaid” in his schemes for social regeneration, dismissing her own artistic aspirations in the proposal scene of Book II.[13] The proposal precipitates a vigorous debate both between the values of art and material social action, and between Aurora’s and Romney’s conflicting visions of the appropriate roles of women and men, with Aurora roundly rejecting Romney even though the two clashing figures evidently love each other with a repressed passion that Aurora’s keen-eyed English aunt discerns.

The “woman question” is further intertwined with the “social question” in Aurora Leigh through the working-class Marian Erle: exploited as a seamstress after she flees her own mother’s attempts to sexually exploit her, then made the focus of Romney’s reforming mission in a marriage he plans to bridge the gulf between classes, then exploited more harrowingly after the marriage is thwarted by Lady Waldemar (amorously interested in Romney enough to engage in manual labour in his “phalanstery” or commune). The deceived Marian ends up impregnated in a brothel in France, where Aurora misjudges her initially when the two meet in ![]() Paris until she hears Marian’s haunting story. Marian then becomes the muse essential to her own further growth as an artist, as well as Romney’s as a reformer, combining body with spirit, the real with the ideal.[14] Through Marian’s story and Aurora’s misreading, EBB intervenes in contemporary debates over prostitution, the “fallen woman,” and violence against women. The vivid scene-painting of settings in London (where Aurora as artist-in-formation ventures into slums she luridly represents without really seeing them), in the Paris of Louis Napoleon, and finally in Florence make Aurora Leigh both an urban and a transnational work. In the continental scenes especially, EBB obliquely addresses Anglo-French politics and Anglo-Italian relations during the Risorgimento: the “rebirth” of Italy through liberation and unification (in England termed the “Italian question”), a subject EBB had earlier addressed in her lyrical, philosophical political poem, Casa Guidi Windows. In this instance, however, not the politics of nations but the politics of a woman-artist’s development is her central subject, from Aurora’s birth in Italy to an Italian mother and English father, to her subjection by her English aunt to a proper young lady’s conventional education (sharply satirized in the verse-novel), to her struggles to establish herself and to live as a woman writer.

Paris until she hears Marian’s haunting story. Marian then becomes the muse essential to her own further growth as an artist, as well as Romney’s as a reformer, combining body with spirit, the real with the ideal.[14] Through Marian’s story and Aurora’s misreading, EBB intervenes in contemporary debates over prostitution, the “fallen woman,” and violence against women. The vivid scene-painting of settings in London (where Aurora as artist-in-formation ventures into slums she luridly represents without really seeing them), in the Paris of Louis Napoleon, and finally in Florence make Aurora Leigh both an urban and a transnational work. In the continental scenes especially, EBB obliquely addresses Anglo-French politics and Anglo-Italian relations during the Risorgimento: the “rebirth” of Italy through liberation and unification (in England termed the “Italian question”), a subject EBB had earlier addressed in her lyrical, philosophical political poem, Casa Guidi Windows. In this instance, however, not the politics of nations but the politics of a woman-artist’s development is her central subject, from Aurora’s birth in Italy to an Italian mother and English father, to her subjection by her English aunt to a proper young lady’s conventional education (sharply satirized in the verse-novel), to her struggles to establish herself and to live as a woman writer.

In 1853, alluding to work on her novel-poem dealing with “the practical & the ideal,” EBB identified “the social question” as central to her focus (BC 21: 111). By 1856, however, mid-nineteenth-century socialist enterprises underway in England, France and America influencing the representation of Romney (see section vi, below) had collapsed or subsided. In contrast, the movement for women’s rights to higher education, more employment opportunities, and legal “personhood” gathered steam in the 1850s. This circumstance explains why the “woman question” that EBB had originally considered only a “collateral object” (qtd. Reynolds 1996, 347) emerges as a pivotal issue in both the verse-novel itself and in the reviews. The experimental hybrid form of her “poetic art-novel” also became a recurrent focus of debate, indicating the key role Aurora Leigh played in contemporary artistic debates, such as the conflict over “past and present” (to use Thomas Carlyle’s terms) as suitable subjects for poetry, and controversies over the emergence of the verse-novel as a widely employed literary genre (see Markovitz). Aligning herself firmly with those who defended present-day subject matter even in poetry, EBB wove topical references throughout: from the parliamentary committees discussing “pickpockets at suck” (III. 612) and producing the “Blue Books” that Romney obsessively reads, to new variations on the polka and waltz (I. 424), to crystal balls (VI. 169) and the mesmeric “od-force” flaming in white heat from the finger-tips of men—but only feebly from those of women (VII. 566-8). References to religious debates are especially notable: especially the apocalyptic millenarianism shaping visions of social regeneration and the ending of Aurora Leigh and the “‘Tracts’ for and ‘against’ the times (I. 394) associated with the Tractarian or “Oxford” movement. The movement led some prominent English Anglicans to convert to Roman Catholicism, or like Sir Blais Delorme, a minor character in Book V, to wear an “ebon cross . . . innermostly” (V. 675-6).

The debates over form are not surprising, given Aurora’s explicit call for an “unscrupulously epic” poem that might “catch / Upon the burning lava of a song / The full-veined, heaving, double-breasted Age” (V: 214-16). This poetic manifesto has been recognized by both nineteenth-century and modern critics as central to the poetic theory, “double vision,” and “unscrupulous” mixing of genres that Aurora Leigh itself embodies. As Kaplan noted in her 1978 Women’s Press edition, the metaphors in the passage alone provoked one Victorian critic (William Caldwell Roscoe in the National Review) to exclaim, “Burning lava and a woman’s breast! and concentrated in the latter the fullest ideas of life! It is absolute pain to read it. No man could have written it” (qtd. Kaplan 13). Kaplan did not note, however, that another male reviewer—the Chartist, poet, and essayist Gerald Massey—later responded to Roscoe’s remarks in an 1862 essay in the North British Review, pointing out that the “apparent incongruities” in EBB’s complex metaphors arise from readers failing to detect underlying “connection[s]” (517-8). Where Roscoe had cried out against the “savage contrast of burning lava and a woman’s breast,” Massey finds instead an allusion to “the lava mould of that beautiful bosom found . . . amongst the ruins of ![]() Pompeii” (517-8) in the lines, “This bosom seems to beat still, or at least / It sets ours beating” (V. 220-21). His reframing illumines EBB’s metaphoric layering of past, present, and future in a “living art” that “presents” (makes present as it represents) “true life” (V. 219-21).[15]

Pompeii” (517-8) in the lines, “This bosom seems to beat still, or at least / It sets ours beating” (V. 220-21). His reframing illumines EBB’s metaphoric layering of past, present, and future in a “living art” that “presents” (makes present as it represents) “true life” (V. 219-21).[15]

Embodying the “double vision” its protagonist calls for, Aurora Leigh mixes the heroic with the mundane, and combines classical allusions with contemporary matter, as in the much discussed epic simile comparing the young Aurora’s masculine education at the hands of her loving father to the young Achilles (I. 722-8). Much as EBB’s “double-breasted age” manifesto connects “beating” hearts in past and present, her vivid letters and those of her contemporaries bring the past into the present for twenty-first century reader, conveying the immediate reactions to her “modern epic” in her own writerly circles in late 1856, early 1857. Among the Brownings’ closer friends, the art critic Anna Jameson wrote to say she was “in a trance of wonder & admiration” at Aurora Leigh, pausing in her second reading to think, “what beauty, what power”; in contrast, an older friend Miss Bayley sounded like Aurora’s aunt in writing to tell EBB that “she does not like Aurora Leigh .. isn’t herself either socialist or spiritualist, & so doesn’t sympathize with any of it . . . objecting besides to the ‘vulgarities’ in the church” (LTA 2: 277n7, 286). The poet wrote to her sister Arabella in February 1857 from Italy that she had heard “(indirectly from various quarters) that ‘never did a book so divide opinions in London.’ Some persons cant bear it,—& others . . Monkton Milnes, for instance, & Fox of Oldham, besides Ruskin & the Pre-Raffaelites, crying it up as what I am too modest to write” (LTA 2:2 87).

The founder of the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood, Dante Gabriel Rossetti, did indeed write to William Allingham that Aurora Leigh was “an astounding work”—though, reflecting the cultural shifts of the 1860s, he would later warn his sister Christina about emulating a “Barrett-Browning” or “modern vicious style” of “falsetto muscularity.”[16] The initial Pre-Raphaelite admiration may have been influenced by EBB’s representation of the fictional Vincent Carrington in Aurora Leigh, a “rising painter” whose philosophy of painting “a body well” captures “the soul by implication” (I. 1095-8): lines evocative both of Browning’s artistic manifesto in “Fra Lippo” and the realism of PRB paintings. Some reviewers of Aurora Leigh also noted Turneresque and Pre-Raphaelite qualities in its vivid scene-painting (see e.g., Aidé and the Literary Gazette, below). Significantly, it was also a painter associated with the Pre-Raphaelites, Arthur Hughes, who produced the first notable painting illustrating the poem in 1860, “Aurora Leigh’s Dismissal of Romney (‘The Tryst’)” [www.tate.org.uk/art/artworks/hughes-aurora-leighs-dismissal-of-romney-the-tryst-n05245]. For the painting, commissioned by Ellen Heaton, a patron of Rossetti, on the recommendation of Ruskin, Hughes appropriately chooses the conclusion to Aurora and Romney’s debate in Book II as a pivotal scene.

In February 1857, the year Swinburne became associated with the second, Oxford wave of the Pre-Raphaelite movement, his letters express the ardent appreciation of Aurora Leigh he recalled in 1898. Writing to his Balliol friend John Nichol, he described it as a “great work” and especially praised a “dramatic power” he did not expect in the poem; it “rivals the male Browning’s character drawing,” he commented. In contrast to those reviewers who interpreted the characters as projections of the author, “Aurora, Marian, and Lady Waldemar” seemed to Swinburne “perfect in idea and execution,” while even slighter characters— “the painter Carrington,” for instance, were “distinct and clearly drawn” (Letters 1. 8). Swinburne obliquely revised these youthful impressions in his 1898 “Preface,” probably influenced in part by Nichol’s much more fault-finding review of Aurora Leigh in the Westminster, along with other critical attacks. Thus, he later remarks that “The career of Aurora in London is rather too eccentric a vision to impose itself upon the most juvenile credulity: a young lady of family who lodges by herself in ![]() Grub Street, preserves her reputation, lives on her pen, and dines out in

Grub Street, preserves her reputation, lives on her pen, and dines out in ![]() Mayfair, is hardly a figure for serious fiction” (x). Swinburne’s “juvenile credulity” may have been more honest, however. As Dorothy Mermin notes, the fact that Aurora lives in what Woolf would later term “a room of one’s own” in London and preserves her reputation while she makes a living by her pen is one of the more “revolutionary” aspects of Aurora Leigh, but less “fantastic” than it seemed (197).

Mayfair, is hardly a figure for serious fiction” (x). Swinburne’s “juvenile credulity” may have been more honest, however. As Dorothy Mermin notes, the fact that Aurora lives in what Woolf would later term “a room of one’s own” in London and preserves her reputation while she makes a living by her pen is one of the more “revolutionary” aspects of Aurora Leigh, but less “fantastic” than it seemed (197).

While Swinburne privately voiced his high enthusiasm in 1857, Ruskin’s public “crying . . . up” of Aurora Leigh in the “Appendix” to his Elements of Drawing (1857) as “the greatest poem which the century has produced in any language” (15: 227) further inflamed the debates its publication provoked. EBB herself attributed his rhapsodic praise (also reflected in a letter to Robert describing Aurora Leigh as “the greatest poem in the English language”) not to her work’s merits, but to the art critic’s agreement with its “philosophy” (LTA 2: 273, 277n4). Her inference is supported by Nichol’s explicit rejection in the Westminster Review of Ruskin’s remarks on Aurora Leigh, together with his philosophy of art’s social power (see below). Privately, Carlyle also proclaimed his disagreement with Ruskin, as he marked up a copy of Aurora Leigh and passed it on, saying it would “never be asked for again” and leaving diverse remarks in the margin, from “Twaddle?” to “goodish” (on the satire of a young lady’s superficial education), “snappish,” “ach Gott!, “devh fine!” (on Romney’s Carlylean description of the gaping social wound), “clever child,” “figurative very!,” “why not call a cab? (on Aurora and Romney’s rain-soaked walk through London in Book IV), and “How much better had all this been if written straight forward in clear prose utterance!” (Kinser and Sorenson).

However one interprets Ruskin’s much cited, but still insufficiently investigated response, it underscores the paradoxes of the intertwined though often contradictory views on art, society, and gender that shaped reactions to Aurora Leigh. The paradoxes emerge if one considers that in The Elements of Drawing, Ruskin eulogized EBB’s poem in the same breath (and sentence) as he commended Coventry Patmore’s conservative depiction of “modern domestic feeling” in The Angel in the House, and that Patmore’s poem and essays, like Ruskin’s later essay “Of Queen’s Gardens” (1865), present views on woman’s role and aspirations diametrically opposed to those Aurora articulates to Romney in rejecting his proposal in Book II, and to those Jessie White saluted in Aurora Leigh. EBB told Arabella in March 1857, that White, then “lecturing all over the united kingdom & Ireland on the Italian question,” had written to say “‘Aurora’ is ‘the rage’ in Scotland’” and that it would “‘do more good for women, than a hundred petitions to parliament” (LTA 2:292). In America, the feminist activist and suffragist Susan B. Anthony had a similar response to the representation of women’s aspirations in Aurora Leigh, reflected in the inscription she wrote on the flyleaf of her copy when she presented it to the ![]() Library of Congress in 1902: “This book was carried in my satchel for years and read & re-read. . . . With the hope that Women may more & more be like ‘Aurora Leigh’” (qtd. Reynolds 1996 x).

Library of Congress in 1902: “This book was carried in my satchel for years and read & re-read. . . . With the hope that Women may more & more be like ‘Aurora Leigh’” (qtd. Reynolds 1996 x).

White’s remarks and Anthony’s testimony suggest why the “woman question” figured prominently in the reviews of Aurora Leigh, with the portrayal of Aurora herself and to a lesser extent Marian also recurrent topics. The representation of Romney and the “social question” is another common thread. Often, however, the hybrid genre and mixed style of the verse-novel are an even greater focus of attention, especially in British and French periodicals. As Mermin observes, Aurora Leigh transgressed “two boundaries . . . of genre and of gender”: the boundaries between “poetry and fiction” and between “masculine and feminine” (223). Nevertheless, far more reviewers than is commonly assumed were either untroubled by the transgression or actively defended what EBB termed the “experiment” of her “form” (qtd. Reynolds 1996, 341). The breaching of other boundaries than gender, especially class distinctions, is another more obliquely registered concern, especially in more conservative British reviews, but again responses are mixed. Moreover, reviewers link their interpretations of Aurora Leigh to an array of other topics, from trends in contemporary visual arts (responses to J. M. W. Turner’s paintings, for example, along with Pre-Raphaelite paintings), to its religious philosophy and/or language, to its representations of international politics.

The vibrant diversity that makes the immediate reception of Aurora Leigh, like the work itself, an index of its age has been obscured by critical legends first promulgated in the period when Aurora Leigh languished in the critical wilderness, and Victorian women poets collectively were almost completely expunged from canonical anthologies. In his 1957 literary biography, epitomizing the generally dismissive view of EBB’s poetry prevailing at the time, Gardner Taplin stated of Aurora Leigh that “the notices in the more influential periodicals were unanimous in their opinion that the defects in the poem far outweighed its merits” (338). Taplin cited G. S. Venables in the Saturday Review as representative of this consensus. In fact, however, Venables’s critique was among the harshest to appear, in a weekly founded in 1855 and sometimes termed the “Saturday Reviler,” notorious for “slashing” articles that boosted sales (Craig and Antonia 67). In 1962, Alethea Hayter similarly though less sweepingly claimed that all Victorian reviewers “thought poorly of the characterization of the adults” in Aurora Leigh (169) in her otherwise often insightful scholarly study of EBB’s poetry. This inaccurate view persisted in some quarters into the 1980s, as in Deirdre David’s assertion in 1987 that Aurora Leigh provoked an “avalanche of negative criticism” in the serious reviews (114).

As Mermin’s balanced overview (222-4) first began to indicate, however, critical responses to EBB’s most ambitious and multi-faceted work mirrored the conflicting literary, social and literary perspectives and agendas that reviewers (and their respective periodicals) brought to the poem. Donaldson’s 1993 annotated bibliography confirms this diversity, and the striking variations that her detailed annotations chart is a feature too of the 23 new American entries between 1856 and 1862 that Cheryl Stiles adds to the “68 articles and reviews” in American periodicals Donaldson identifies (Stiles 243). Notably, both of these resources include shorter notices and reviews in the daily and weekly press that often preceded discussions of Aurora Leigh in the monthlies and quarterlies.

This initial wave of reviews underscores the extent to which Aurora Leigh constituted a transatlantic publishing phenomenon and reveals the “buzz” its “advent” produced among an expanding audience, a reaction further intensified by the media coverage itself. Moreover, then as now, reviewers avidly consulted, echoed, and argued with earlier reviews. Thus, the daily and weekly press reviews provoked and/or set the terms for the more extended critical analyses that followed. Indeed, one of the reasons why reviewers in the more conservative gate-keeping periodicals bore down so severely on Aurora Leigh was precisely to counter the admiration already expressed for it by a more “promiscuous” and mixed audience of critics and their readers in daily newspapers and weeklies. The focus on asserting literary conventions and standards in the traditionally influential monthlies and quarterlies was furthermore compounded by their economic competition with the daily and weekly press in the rapidly expanding print culture of the period.

Aurora Leigh itself includes a vivid description of the changing material conditions of writers for mid-nineteenth-century periodicals in Book III, where Aurora describes her attempts in London, in a third-floor garrett, to earn her “bread” and “breathing room” for her “veritable work” (l. 328) of poetry:

I wrote for cyclopædias, magazines,

And weekly papers, holding up my name

To keep it from the mud. I learnt the use

Of the editorial ‘we’ in a review

As coutly ladies the fine trick of trains,

And swept it grandly through the open doors

As if one could not pass through doors at all

Save so encumbered. I wrote tales beside,

Carved many an article on cherry-stones

To suit light readers,—something in the lines

Revealing, it was said, the mallet-hand,

But that, I’ll never vouch for: what you do

For bread, will taste of common grain, not grapes . . . (310-322)

As Dallas Liddle notes, “[t]o write for periodicals in this passage, has not meant adapting Aurora’s own ideas and words for a different mode of external publication [than her poetry], but alienating herself from her own voice,” and taking on “voices prescribed by the genre requirements of the periodical press” (15). Moreover, Aurora’s remarks suggest a “troubling ascendency of the periodical genres, to the detriment of the literary ones” (17). Liddle, drawing on the theory of Mikhail Bakhtin, may overstate a “binary” difference between journalistic and literary modes (see Hughes, “Media” 294-6). Nevertheless, it is useful to keep the pressures on periodical writers that Aurora specifies in mind (earning their “bread,” meeting deadlines, satisfying editors) in assessing the critical assessments of Aurora Leigh.

iv. The Reception of Aurora Leigh in the Transatlantic Daily and Weekly Press

First to the mark in reviewing Aurora Leigh was the London Globe and Traveller, on 20 November 1856, five days after it appeared. The reviewer introduced it as “a wealthy world of beauty, truth, and the noblest thoughts,” a “gem” glowing “with the life blood of sound humanity”—both a “new, true, and original poem” and also a “first-rate prose novel.” The Globe appreciated the complexity and topicality of Romney’s characterization as a social reformer (see below), noted the keen satire in the “vigorously painted” Lady Waldemar, and especially praised the representation of Marian as “more lovely and poetic than anything else in the poem”: not “excelled in pathos by anything . . . in poetry or fiction, nor in terrible truth by any social misery and crime in yesterday’s police reports.” These remarks on Marian established a pattern that would prevail in a surprising number of reviews (see section vi). The notice concludes by describing Aurora Leigh in terms akin to those used by Ruskin and Fox as “a poem of this age, —for this age and for all time.”

The Literary Gazette reviewer, on 22 November, even more enthusiastically begins, “The critic who will undertake to gauge the merits of this poem, to estimate how much it adds to the sum of the world’s wealth of written thought and beauty, and to assign its rank among the master-works of genius, will have no easy task.” Describing himself as still “too much dazzled by the splendor in which we have been wrapped by the genius of the poet” to undertake this task, the reviewer also warns that Aurora Leigh is “no poem to be taken up for pastime”; it requires the “exercise” of the reader’s faculties of “eye, and ear, and soul.” Into it, “Mrs. Browning has thrown the whole strength of her most noble nature. . . . All the powers which were indicated in her former works seem to us to be displayed in the present poem in perfection. She wields the lightning of her genius with Jove-like freedom.” Despite the poem’s “slender vein of incident,” there is “no flagging of the pulse. Everywhere there is power, everywhere variety” (917).

Notwithstanding such purple language, the Literary Gazette critic zeroes in on the questions of form and the debate over past and present subject matter central both to Aurora Leigh itself in Aurora’s poetic manifesto in Book V and to the periodical debates it engendered. The first passages this reviewer notes at length are those on epic and “double vision” (“The critics say the epic has died out”) and the “double-breasted Age,” presenting them as “words for our young poets to ponder over.” While such words may lead to imitations of Aurora Leigh “diluted in every imaginable medium by the weaker sort,” the reviewer observes, they can also stimulate stronger young poets to “take courage” from the example of Mrs. Browning, rather than “galvanising the simulacra of the past” (917). Later reviewers like Roscoe in the National Review who rejected the poetics of the contemporary in Aurora Leigh seem to have been “galvanized” in turn by these warring words. The Literary Gazette reviewer also highly praises the descriptive “power” of Aurora Leigh, and is the first of many to cite the passage describing Marian’s babe (“She threw her bonnet off . . .”) as an exquisite instance of such description: “a picture, as perfect in force of outline and in its richness of coloring as anything in Tennyson.” He notes too the very different “Titianesque glow” in the portrait of Lady Waldemar at Lord Howe’s party, with her “aspectable breasts” white as “milk,” and he compares the railway journey from Paris to ![]() Marseilles (Book VII. 395-452) to Turner in its “power” of turning to “beauty the funnel and smoke” of unpoetical, modern subjects (917-8). The Literary Gazette reviewer was not the only critic to compare EBB’s painterly technique to Turner’s (see Aidé and Aytoun below). Although this review is clearly written by someone conversant with the arts, appeared on the same day as Chorley’s in the Athenaeum (see below) in a long-established and influential literary magazine, and is almost as extended, Chorley’s is repeatedly cited in the scholarship on Aurora Leigh, whereas the Literary Gazette review is not.

Marseilles (Book VII. 395-452) to Turner in its “power” of turning to “beauty the funnel and smoke” of unpoetical, modern subjects (917-8). The Literary Gazette reviewer was not the only critic to compare EBB’s painterly technique to Turner’s (see Aidé and Aytoun below). Although this review is clearly written by someone conversant with the arts, appeared on the same day as Chorley’s in the Athenaeum (see below) in a long-established and influential literary magazine, and is almost as extended, Chorley’s is repeatedly cited in the scholarship on Aurora Leigh, whereas the Literary Gazette review is not.

Other reviews in the daily and weekly press similarly greeted Aurora Leigh in terms that conveyed its power and originality, even when more mixed in their opinions. Conveying the high expectations surrounding its publication, The Leader review opens, “When, some weeks ago, we anticipated the delight of a new poem from Mrs. Browning, we never, in our keenest expectations, thought of receiving so fine a poem as Aurora Leigh, which surpasses in sustained strength and variety, anything English poetry has had since Childe Harold” (1142). The reviewer goes on to note “many faults,” but does not object to the verse novel form in observing that this novel is “sung,” indeed “sings of our actual life . . . and the social contests of our day.” Many poets have told “stories in verse,” he remarks, instancing Byron, Scott, and Tennyson in The Princess and Maud, and describing Tennyson as doing so with “indifferent success.”

At the same time, the Leader critic divorces the forms that Aurora Leigh unites by considering it as a novel one week, in the first half of the review, and as a poem in the next weekly installment. As a novel, it is “second-rate” like most other stories in verse, even by famous authors like Wordsworth, the reviewer remarks—although “the story draws us onwards, filling the eyes with tears, and the heart with . . . noble emotions,” (1143). As a poem, however, it embodies “affluence and effluence of mind” and “exquisite and easy utterance”; presents “meditations and feelings, expressed in imagery and musical phrase, but not sacrificed to these elements”; and manifests the “constant presence of a noble nature” in “song that is the song of the mind.” The two faults the Leader reviewer identifies in Aurora Leigh as a poem include long sections “without concreteness” after “pages of concrete, picturesque, direct verse” and its “offensive” use of “the name of God”: faults common in “poets of the ‘Spasmodic School,’” but distressing in “a poet in every way so superior as Mrs. Browning” (1169). Notably, this is one of the only instances in which the term “Spasmodic” is associated with, but not applied to Aurora Leigh in the 1856-58 reviews, despite the view in recent scholarship that EBB’s contemporaries viewed it as a “spasmodic” poem (see Aytoun, 1857 below).

Like The Leader review, the Spectator review included some fault-finding, objecting especially to the “disagreeable” resemblance to Jane Eyre in Romney’s blinding as George Eliot subsequently did, as well as to melodramatic incidents, and to characters too “stationary” and undeveloped (427-29). At the same time, the Spectator described Aurora Leigh in terms conveying its vitality and especially its power, employing “Titaness” analogies that may have influenced Dickinson’s famous reference to EBB’s “Titanic opera” (especially since the review was reprinted in ![]() Boston in Littel’s Living Age). “There was always something of the Titaness in Mrs. Browning,” the review begins, finding “the old anarchic nature of the Titaness still discernible” in Aurora Leigh. Nevertheless, although her “steeds still toss their heads somewhat wildly for well-bred carriage horses . . . and would rather ride with Mazeppa than take a ticket by the Great Western,” Aurora Leigh is “a great step forward” in “execution” from her earlier works. Its plan “is too large and complex,” but its author “has succeeded in writing brilliantly and powerfully,” “touched upon social problems with the light of her penetrating intellect and the warmth of her passionate heart,” “sketched characters as a sensitive and observant woman can,” and “dramatized passion with a force and energy that recall the greatest masters of tragedy” (427-8). Like the Globe and Traveller and Literary Gazette reviewers, the Spectator critic did not object to the mixed genre and style of Aurora Leigh. On the contrary, he commends the “free and natural manner” of the verse, losing “little of its ease and lightness in more prosaic parts of the poem, and gain[ing] in much larger proportion in the impassioned parts by being in verse” (428).

Boston in Littel’s Living Age). “There was always something of the Titaness in Mrs. Browning,” the review begins, finding “the old anarchic nature of the Titaness still discernible” in Aurora Leigh. Nevertheless, although her “steeds still toss their heads somewhat wildly for well-bred carriage horses . . . and would rather ride with Mazeppa than take a ticket by the Great Western,” Aurora Leigh is “a great step forward” in “execution” from her earlier works. Its plan “is too large and complex,” but its author “has succeeded in writing brilliantly and powerfully,” “touched upon social problems with the light of her penetrating intellect and the warmth of her passionate heart,” “sketched characters as a sensitive and observant woman can,” and “dramatized passion with a force and energy that recall the greatest masters of tragedy” (427-8). Like the Globe and Traveller and Literary Gazette reviewers, the Spectator critic did not object to the mixed genre and style of Aurora Leigh. On the contrary, he commends the “free and natural manner” of the verse, losing “little of its ease and lightness in more prosaic parts of the poem, and gain[ing] in much larger proportion in the impassioned parts by being in verse” (428).

Other English and American newspapers were positively glowing, in relation to both the form and subject matter of Aurora Leigh. For instance, the London Daily News termed it “the greatest poem ever written by woman” and classed it among “the master works of the highest order of genius.” The reviewer anticipates “a large number of opponents to the book”: those who might object to Aurora as a “‘strong-minded woman’” because they believe that “the functions of women are to be limited to perpetuating the race”; there will also be those who object to the verse novel’s mixed style and to “colloquialisms” that “give their sense of genteel expression a shock.” Dismissing these probable objections, however, the reviewer lauds the “great human interest” and “astonishing power of subtle mental analysis” in Aurora Leigh. “Mrs. Browning brings the broad blaze of imagination to bear upon the phenomena of internal consciousness with the same power that the old poets did upon the appearance of the external world,” the reviewer remarks, vigorously defending the poem’s subjective focus against the “doctrine that poetry should always be objective.” The “remarkable” learning of Aurora Leigh is also praised: a learning that is not pedantic, but that “adds vitality to conceptions and force to expressions,” as in the use of “Greek history and mythology.” The reviewer concludes this unusually long newspaper notice with a “fuller confidence than ever” that Aurora Leigh will lead its author’s “countrymen and countrywomen” to recognize “her place among those whose genius has rendered their names immortal” (Daily News 1856, 2).

The Examiner critic uses more moderate terms than the Daily News critic. Nevertheless, the Examiner reviewer insightfully elucidates the “philosophical love story” in Aurora Leigh treating “two kinds of effort” embodied in a “pair of lovers”— Romney the “Christian socialist” and Aurora the “poetess,” each with lessons to learn. The Examiner critic further notes the “obvious purpose” in the much discussed blinding of Romney and recommends that Aurora Leigh be “read twice” to appreciate the “great truth living and expanding in the verse” and the “beauty” of insights on “almost every page” (756).

As for notices in American daily papers, EBB described some of these as “ecstatical,” noting, for example, American “delight” in the scene of Romney’s marriage in the church elsewhere criticized by Chorley in the Athenaeum (LTA 2: 279). The New-York Daily Times reviewer commented on the “easy grace” of the blank verse, “such as no living pen can command in greater perfection” (qtd. LTA 2: 283n12)—contrary to the much more cited denunciations of it by Chorley and Aytoun analysed below. This notice also praised EBB’s “highly felicitous” female characters, compared her portrayal of Marian to Wordsworth’s portrayal of humble characters, and drew parallels between her portraits of London life and Thackeray’s. The Boston Daily Advertiser was similarly enthusiastic in describing Aurora Leigh as a poem to be reread, “committed to memory, and quoted from, and never forgotten,” while the Boston Courier descried it as “a triumph of clear, strong purpose, imaginative insight, and intellectual power” never displayed before by a woman, even though all her characters talked “exactly as Mrs. Browning would” (qtd. Donaldson 61, 69).

Such responses indicate that EBB was not deluded in her comments on the response to Aurora Leigh. She had braced herself for “furious abuse” because of its candour regarding Marian Erle’s story in particular (although it was Lady Waldemar’s frankly erotic language that reviewers most often critiqued as “coarse”). But she found that “the daily and weekly press” was “for the most part, furious the other way,” noting as “exceptions” the Press, the Morning Post and the Dublin Tablet (Browning, E.B., Letters, ed. Kenyon 2: 249). There were other negative notices that she did not note: the Guardian, for example, condemned the “coarse and disagreeable” story and the “loose and unmelodious” versification” (qtd. Donaldson 62). The Catholic Tablet most vigorously denounced the much anticipated “advent of this new ‘Aurora’”—in an ironic application of the term Swinburne would later use—and found “the artist-workwoman, the high-souled woman with a ‘mission’ . . . a terrible companion in a journey of twelve thousand lines.” Condemning the form of Aurora Leigh, the Tablet described it as “like a translation into blank verse of a French novel by Frederic Soulié” (462). Richard Simpson’s review in The Rambler, another Catholic periodical, suggests that religious affiliations may have contributed to the intensely negative Tablet response (see below). Similarly, despite commonalities in the reaction to Aurora Leigh in different countries, nationality at times clearly contributed to varying patterns of response in Britain, America, and European countries such as France, as Section VII demonstrates.

v. British Periodical Debates: Gender, Genre, and the Politics of Form

The polarized, but often admiring responses to Aurora Leigh in the transatlantic daily press are played out in a magnified form in the more extended periodical reviews—especially in Britain, but also to a degree in America. In Britain, more conservative periodicals such as Blackwood’s, the National Review, and the Saturday Review published largely negative commentaries, as did, more unexpectedly for EBB, the Athenaeum. Taplin in 1957 drew exclusively on the most conservative reviews in summarizing Victorian critics’ response to the poem: “They asserted it was too hastily and carelessly written, that it was far too long, that it was lacking in dramatic appeal, that the characters were poorly conceived, that the incidents in the story were hackneyed, implausible, and many of them unnecessarily coarse and revolting to good taste” (338). Even the more condemnatory reviews were less unvarying than Taplin’s generalizations suggest, however. More importantly, there were also predominantly or enthusiastically positive assessments in the British Quarterly Review, the Monthly Review, the New Quarterly Review, and the Edinburgh Weekly Review. As for the prestigious Westminster Quarterly, it represented both sides of the question, with warm praise in an anonymous review by George Eliot and the more critical, but still not consistently “negative” follow-up review by John Nichol noted above. In another case—the Dublin University Magazine—passionate praise followed by contradictory caustic critique raises the possibility of two voices in internal conflict within the same mind, or two hands at work in one review, as I indicate below.

G. S. Venables’s review of Aurora Leigh in the Saturday Review, although characterized as “typical” by Taplin (338), represents the negative extreme: unsurprisingly, considering the weekly’s characteristic culture and politics. From its inception in 1855, the Saturday Review, known for its irreverent “slashing” (see above), often took a position hostile to the “woman question.” Its stance was later epitomized by its most-read article over decades of publication: Eliza Lynn Linton’s 1868 attack on “The Girl of the Period.”[17] One of the shaping spirits of the Saturday Review, Venables opens his review of Aurora Leigh with the statement, “The negative experience of centuries seems to prove that a woman cannot be a great poet,” then uses his denunciation of the “fable, manners, and diction” in Aurora Leigh to drive home his thesis with the self-conscious cleverness also cultivated in the Saturday. EBB’s characters are “unreal”; the incidents of Aurora Leigh are “inconceivable” incidents; and its “unbroken series of far-fetched metaphors” are an example of “feminine misadventures in art”—although he does acknowledge “a capacity for humorous satire” in the portrait of Aurora’s “prim, dry, narrow English aunt” (776-7). Describing the “artificial key” of the clashing dialogues between Aurora and Romney, Venables fancifully compares them to “[t]wo Pythonesses singing their responses in parts” but out of harmony (776). Aurora, however, is the “Pythoness” (i.e., the priestess to Apollo, god of poetry), to whom Venables most objects. Indeed, he finds the poem is at its best “[w]hen Aurora forgets that she is a poetess—or, still better, when she is herself forgotten” (778). Venables’s “Pythoness” image in 1856 in the Saturday Review was later elaborated by Aytoun in his 1860 Blackwood’s “Poetic Aberrations”: an all-out denunciation of the “fair sex” meddling in politics and EBB’s “oracular raving” in Poems before Congress. Aytoun here invokes Plutarch’s description of the “Pythoness,” who, “going into the sacred place to be inspired, . . . came out foaming at the mouth, her eyes goggling, her breast heaving, her voice indistinguishable and shrill, as if she had an earthquake within her labouring for vent” (1860, 492).[18]

While Venables is cleverly vitriolic, Robert Alfred Vaughan’s assessment of Aurora Leigh in the British Quarterly Review approaches the other end of the spectrum, a feature possibly related to the periodical’s close association with the English Dissenters (Palmegiano 81) and thus a political and religious culture both of the Brownings shared. Vaughan, a founder of and regular contributor to the British Quarterly, objects to neither Aurora nor the portrayal of Romney. Instead, he notes the realistic delineation of fallible “excess” in each character in a work that represents the “hereditary feud between the imaginative mind and the practical” in a tale reflecting on “some of the most anxious questions of our time” (263). He also commends the work’s “sound philosophy,” its “many . . . wise and large-minded thoughts, vigorously expressed in felicitous and glowing language,” citing as an example Romney’s eventual recognition of the problems in “toiling to carve the world anew after a ‘pattern on his nail.’” For Vaughan, the author of Aurora Leigh is a successful artist and a sage: “Our generation scarcely numbers more than one or two among its master minds from whom we could have looked for a production at all to rival this in comprehensiveness—a poem with so much genuine depth and so free from obscurity. The results of abstract thinking are here, and yet there is no heavy philosophizing of set purpose. A warm human life meets us everywhere. . . . Men and women are introduced who learn philosophy by actual life” (265). Like several of the reviewers in the daily and weekly press, Vaughan also approves the “originality” of “a modern novel in the form of an epic poem,” despite its “apparent incongruity” (263). Though he finds the long, poetic speeches sometimes lose their “conversational character,” he finds them “in spirit dramatic,” in a “story . . . “told clearly and well, yet so imaginatively that the reader can never think to himself—‘All this would have been better said in prose’” (266-67). He also commends the flexible versification in which the poet “has endeavoured to approach as nearly to the language of daily life as was possible without becoming prosaic or colloquial” (263).

The New Quarterly Review, in what EBB saw as a “favorable notice” (LTA 2: 279), similarly approved the generic hybridity of Aurora Leigh: “The incidents of the book would have thrilled in a novel—the loftiness of the philosophy would have allured in a treatise—together, they compose a poem, whose action criticism must allow to be as sustained as its scope is large and noble” (qtd. LTA 2: 283n11). Other reviewers especially noted the virtues of the first-person perspective and scene-painting in Aurora Leigh in terms that freely mixed literary genres, as well as poetry and painting. This mixing is evident in Aidé’s response to Aurora Leigh as a “modern epic” and “three-volume novel” in the Edinburgh Weekly Journal (see above). Aidé—a social acquaintance of the Brownings—observes that Aurora Leigh marks “an epoch in literature” because it is, “in many respects, an innovation on long accepted uses in poetry.” He approves both its generic hybridity and the novelistic perspective which gives a “vividness to the narrative.” As an “autobiography,” much of it “written soon after the events it records,” it has “the freshness of a journal,” he remarks (7). Aidé, who was himself a painter and musician as well as novelist and poet, also notes the “rich and glowing pictures of nature” in the poem and its “pre-Raphaelite delicacy of touch,” combined with the recognition that such minute fidelity to nature is “not the aim and end of Art.” This last point, evidently a glancing blow at the philosophy Aidé saw as underlying Pre-Raphaelite paintings (8), may have influenced D. G. Rossetti’s description of Aide’s review in the Edinburgh Weekly Journals as “poorish” (Letters 1: 82). Like the Literary Gazette reviewer (see above) and Aytoun (below), Aidé furthermore drew comparisons with Turner, though focusing on a different passage: in Aidé’s case, the “picture of Paris” in Book VI, which he described as “absolutely Turneresque in its vivid brilliancy and breath of touch” (8).

Comments like these form a striking contrast to the often cited condemnations of the mixed genre and style of Aurora Leigh in reviews by Chorley, Coventry Patmore, and Aytoun. Chorley’s Athenaeum attack on Aurora Leigh for being not “a poem, but a novel, belonging to the period which has produced “Ruth,” and “Villette,” and “The Blithedale Romance”’ is among the best known of these critiques, especially his objections to the associated stylistic “mingling of what is precious with what is mean . . . of the grandeur of passion and the pettiness of modes and manners. . . . Milton’s organ is put by Mrs. Browning to play polkas in May-Fair drawing-rooms” (1856 p. 1425). Whereas The United States Magazine reviewer assumes that EBB is not playing Milton’s “sonorous” organ at all, but rather turning to Shakespearean models for a more “human” blank verse (see below), Chorley measures her against Milton. Regarding the poet’s intent at least, the evidence of EBB’s essay “The Book of the Poets” (1842) and twenty-first-century studies confirm the Shakespearean models for what Josie Billington terms the “oscillation between fixity and fluidity” in the blank verse of Aurora Leigh (87). In his close analysis of the poem’s versification, Robert Stark similarly demonstrates that, in emulating Shakespeare (65), EBB radically deviated from Victorian “expected norms” in her “use of caesura, elisions, and metrical substitutions,” as she “transformed blank verse into a pliant verse-form well suited to the age of the novel” (49-52).

A closer look at Chorley’s critique of EBB’s stylistic “mingling” in the context of his review as a whole suggests it was not only the mixed form of Aurora Leigh that disturbed him. He begins his assessment of the verse novel by framing it as a “contribution to the chorus of protest and mutual exhortation, which Woman is now raising.” He also satirizes the mingling of “Rank and Rags” readers encounter when Romney the “socialist gentleman” stages his wedding to the working-class Marian (1425). As these responses to the work’s political subject matter imply, Chorley—though generally sympathetic to women writers—was not engaged by either the “woman question” or the “social question.” The anger and fear aroused in him by the political content of Aurora Leigh (more transparently revealed in his later obituary notice marking EBB’s death)[19] may underlie what she found to be the most “unfair & partial” aspect of his “analysis”: that it ignored not only “half” of the “outside shell” of her verse novel’s plan, but also missed entirely what she termed “the double-action of the metaphysical intention” (Florentine Friends 115). Other reviewers came much closer than Chorley to capturing one aspect of this “double-action”—indicated in one of EBB’s working notes for Aurora Leigh, “The Ideal against the practical” (qtd. Reynolds, 1996 349). For instance, the National Magazine critic noted of Aurora and Romney: “The aspiring and scornful idealist finds the noblest use of her gifts in their practical application. The material worker learns that man’s social progress is blindly aimed at unless pursued in light of his immortality” (314).

EBB’s “metaphysical intention” was also not appreciated by Patmore in his review of Aurora Leigh, unsurprisingly given politicized contexts that are again not immediately evident from the review itself, with its apparent focus on aesthetic concerns. She heard in advance that Patmore would be reviewing Aurora Leigh for the North British, and expected him to make “mince-meat” of her, given his publication earlier in 1856 in the National Review of an “article upon women, putting us all in our places most dogmatically” (LTA 2: 262). In the National Review article, Patmore praised the qualities he most admired in women (“charming subordination . . . flattering inferiority”) and denounced “the equality of man and woman” as the most “monstrous” of the “births of modern philosophy” (cited in Florentine Friends 114n12): Writing to Isa Blagden, EBB commended the “very vigorous articles” Bessie Rayner Parkes had written in reply to Patmore’s “infamous doctrines” in the National Review (Florentine Friends 112). In his subsequent North British assessment of Aurora Leigh, Patmore is subtler in expressing his doctrines on women and their place. Like Chorley, he focuses on its mixture of poetry with passages that “ought unquestionably to have been in prose” or “in a review” in analyzing it as a “novel-in-verse, or present-day epic” (237). However, he chooses not to dispute the question at length because he “dissents altogether from certain of the views it advocated” on “Life and Art,” especially its too “sweeping” rejection of “‘conventions,’ which are society’s unwritten laws” (240-41). The inclusion of gender as well as genre and style among these “unwritten laws” is obliquely implied by his dismissal of the “elaborately depicted” portrayal of Aurora’s “development of her powers as a poetess” as “uninteresting” because “Mrs. Browning is herself almost the only modern example of such development” (242).

Aytoun’s review of Aurora Leigh in Blackwood’s in January 1857 is more explicit than either Chorley’s or Patmore’s in revealing the interconnections between aesthetic “conventions” and gender and class hierarchies. EBB did not expect Blackwood’s, given the journal’s long established Tory politics and culture, to be favorable; in fact, Robert Browning expected “some personal blackguardism.” On reading the review, however, EBB thought it “wrong, but not malignant,” written by someone of “the elder school . . . who judges from his own point of view” (LTA 2:279). Aytoun opens his assessment of Aurora Leigh by framing it in the context of the “woman question,” much as Chorley does, but more flamboyantly: “Mrs. Browning takes the field like Britomart or Joan of Arc” (25). After a summary of what he describes as its “fantastic, unnatural, exaggerated” story (1857, 32), terms similar to Venables’ in the Saturday Review, he proceeds to “maintain that woman was created to be dependent on the man” and that “the extreme independence of Aurora detracts from the feminine charm . . . we might have otherwise felt in so intellectual a heroine” (33). Having insisted on the distinction between the sexes, he turns to insist on “the distinction between a novel and a poem,” observing that “Artists, like architects, must work by rule” (34-5) and condemning the “tendency to experiment” as a “morbid craving for originality” (39).

This generic distinction, framed in a larger context emphasizing gender distinctions, is further intertwined with rules about representing the present as opposed to the past and rules for the proper separation of the social classes. Citing the “double-breasted Age” passage, Aytoun rejects outright the poetics of the contemporary that it articulates. Roscoe in the National Review does the same in arguing that the “greatest poet” is “of no age” and criticizing “high-wrought” metaphors like the lava and “burning breasts” of the “double-breasted Age” (253, 245, 247) in exclamations that are themselves “high-wrought,” as Kaplan’s later citing of them indicates (see above). Nevertheless, Roscoe’s analysis of a poetics privileging the contemporary is, in fact, more multi-faceted and thought-provoking than Kaplan’s brief citation from it suggests. Aytoun’s treatment of this same poetics is, in contrast, relatively one-dimensional and declamatory. “All poetical characters, all poetical situations, must be idealized,” he asserts; “poets in all ages [have] shrunk from the task of chronicling contemporaneous deeds,” until “time has done its consecrating office” (1857, 34-41). Hence, he argues that poetry’s idealism must also not be mixed with the prosaic style and content of the novel, and condemns EBB’s mixing of “passages of sorry prose with bursts of splendid poetry.” To underscore his arguments, his review presents several more prosaic passages in Aurora Leigh formatted as if they were prose (35). Aytoun further invokes Shakespeare’s plays as a model of how a suitably dignified form of diction and blank verse should separate “low comedy” and “discourse in prose” from higher subjects and ranks (37), whereas, he observes, “Mrs. Browning follows the march of modern improvement. She makes no distinction between her first and her third class passengers, but rattles them along at the same speed upon her rhythmical railway” (37). Although Aytoun does usefully distinguish “the humble” and the “mean” as poetical subjects (36), these terms themselves, combined with his railway analogy, speak to his class assumptions.

The link between Aytoun’s aesthetic rules and resistance to social reform is made clear when he confesses that he has “not much faith in new theories of art,” because he classes “them in the same category with schemes for the regeneration of society” (39). Intriguingly, he also compares the “brilliantly colored pictures” in Aurora Leigh to Turner’s as Aidé and the Literary Gazette critic do (see above), but rather than seeing this as cause for praise, he finds both artists “extravagant in the vividness” of their “tints,” with a parallel tendency to “multiply” and “intensify images” (37)—as if he objects to the visual mixing associated with Turner’s impressionistic effects, along with the mixing of genders and classes. As Jason Rudy shows, Aytoun elsewhere assailed what he saw as the “unruly formal styles” of the “Spasmodic School” in the 1850s, in part because of mid-Victorian anxieties created by “increasingly heterogeneous culture” (78), his resistance to the displacement of “objective truth” by “subjective and physiological experience” (81), and the working-class origins of Spasmodic poets: features leading critics to interpret their aesthetic challenges as a “political challenge” (102).

Although Aytoun inscribed the term “Spasmodic” in literary history through his famous parody Firmilian: A Spasmodic Tragedy (1854), he does not actually term Aurora Leigh a “spasmodic” poem in reviewing it in 1857, as modern critics sometimes do.[20] He does, however, obliquely allude to Spasmodic poets such as Alexander Smith, Sydney Dobell, and Philip James Bailey in the extended diatribe concluding his essay, where he turns to castigate “our ‘new poets’ . . . tearing their hair, proclaiming their inward wretchedness, and spouting sorry metaphysics in sorrier verse” (40). Aytoun less clearly distinguishes EBB from poets identified as Spasmodic than The Leader critic cited above does; at the same time, he acknowledges her “extraordinary powers” (41) and encourages her to take a different path. EBB herself read at least extracts from Spasmodic poets such as Smith and Dobell with some interest, but a mixed response.[21] Among the only other references to the Spasmodics in the 1856-58 reviews of Aurora Leigh is the Boston Christian Examiner’s comparison of EBB’s style to Smith’s “vehement extravagance” (qtd. Donaldson 71) and passing mention of “Bailey’s Festus” in the conclusion to the Dublin University Magazine review (470).

This ![]() America, as in England and Dublin review in an Irish Protestant periodical modelled to some extent on Blackwood’s presents a strangely contradictory assessment of Aurora Leigh. The review first mounts a vigorous defense of Mrs. Browning’s “artistic purpose and design” in representing “the common-place and prosaic ever touching upon but not blending with the sublime and poetic.” Such juxtapositions appear “again and again” in “real life,” and in Shakespeare’s plays, where “the coarse or foolish, or the low in thought and expression” follows “quickly upon the elevated and poetic,” the review states, using the Shakespearean parallel to vindicate the stylistic mixing of Aurora Leigh, not to critique it as Aytoun does. The review also seems to take aim at Chorley’s Athenaeum review, in commenting that “we hold very cheaply this superficial criticism” that condemns the introduction of a “prosaic and inane” scene in “a fashionable London ball-room” into the “high thinking” about the role of “Art” in Book V of Aurora Leigh. As the Dublin University Magazine review notes, the verse novel’s author could easily have clothed “the sentiments of the ball-room men and women in poetic language; but she then would have been neither true to their nature nor to her own art” (465).