Abstract

This essay explores the trial of James Stuart on the charge of murder, for fatally shooting Alexander Boswell (James Boswell’s son) in a duel. The dispute between Stuart and Boswell was part of the acrimonious paper war between Scottish Whig and Tory newspapers. Stuart’s acquittal as well as the mode of his defense, largely conducted by Henry Cockburn and Francis Jeffrey (both Whig lawyers and the latter the editor of the Edinburgh Review), demonstrate the mutual reliance and interconnections between the periodical press, the illegal practice of dueling, and the criminal court system.

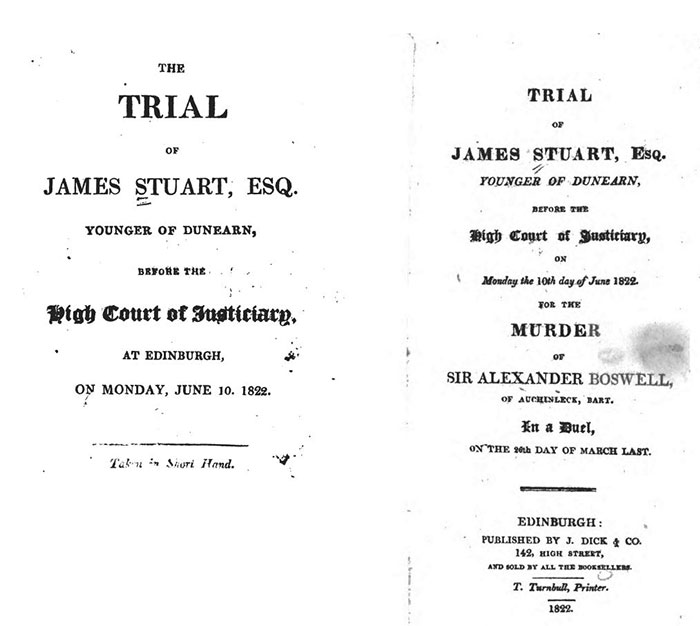

On the 10th of June 1822, James Stuart was acquitted in an eighteen-hour trial of the murder of Sir Alexander Boswell, the eldest son of Samuel Johnson’s biographer, James Boswell. The two had fought a duel on 26 March of that year, and the “Introduction” to one account of the proceedings declared that “there does not occur in the annals of our country, the record of a trial which has excited so general an interest in the public mind, as the trial of Mr. Stuart” (Trial I 3). The courtroom “on the opening of the doors was immediately filled to excess” (Trial I 8), in part because newspapers and magazines had reported on the duel, and in part because the duel itself was an extension of feuding Scottish newspapers. Public interest was sustained afterwards as two different accounts of the trial (in addition to a broadside published the day of the verdict) were quickly produced, a forty-three-page pamphlet published within five days of the event and a book of more than 200 pages within two weeks, based on shorthand according to its title page.[1] The latter account was commended by the Eclectic Review for producing the speeches by the defense’s advocates “with unusual accuracy” (“Art. VI” 170).

The Eclectic and several other periodicals took the trial as the occasion to consider the place of dueling for modern society, and in particular the interconnections between the law, the press, and this seemingly antiquated and allegedly private form of justice. Further, in early nineteenth-century fiction, pamphlets, and periodicals, duels—whether fought, threatened, imagined, metaphorical, or insinuated—were entwined with notions of gentlemanliness and masculinity. In Austen’s Pride and Prejudice, for example, Mrs. Bennet fears that her husband will be killed in a duel with Wickham as a consequence of their daughter Lydia’s elopement.[2] In 1824, an anonymous publication, The British Code of Duel: A Reference to the Laws of Honour, and the Character of Gentleman, was inscribed to Prince Frederick, “His Royal Highness, The Duke of York, who has evinced in his own person the most delicate sense, and prescribed to the Army the just limits, of the present Subject”; the author concludes that, “under the laws of honour,” it is only “legitimate gentlemen; whose good-breeding, manners, and proper feeling, are sure beacons for the avoidance of quarrel!” (85). The text’s idealization of the duel as a codified process and of “the gentleman” as an uncontested category with clear markers to identify its members distorts both the ad hoc nature of many duels and the claims and counterclaims about status (in both the press and in preambles to dueling) that disclosed instability and anxiety regarding the social and economic construction of the gentleman.

In reviewing Trial II, the longer account of Stuart’s trial for killing Boswell, the Eclectic selected for its running title “Abuse of the Press, and Duelling” and is characteristic of periodicals in linking the excesses of the press with the fatal duel, although different journals located those excesses differently, depending on their political perspectives. Both the courts and the press served as the adjudicators of public reputation, and recognized the duel, therefore, as an ancient form of their own processes. The Eclectic’s analysis of this connection notes that Boswell’s death “did not originate in personal and private animosity, but is immediately connected with a System, whose direct tendency is to throw among us the fire-brand of discord, by giving unbridled scope to the tongue of slander” (“Art. VI” 170). Like dueling and its “falsely called . . . laws of Honour” (170), the System of the press was less a law unto itself—print was regulated by libel, sedition, taxation, and other laws—than one that both complemented and competed with common law and thus appeared to have ever widening reach. The power of the press was supported by “not merely those who directly contribute to its prosperity, but [by] every individual who, influenced by curiosity or any other motive, contributes to its subsistence,” and thereby to “its criminality” (174).

The trial of Stuart demonstrates the interdependencies between the legal system, posing as an ultimate horizon of justice, and both the press and the duel as supplemental structures on which that system depended. In specific, as personal reputation was increasingly recognized and mobilized as a valuable property in the age of “industrialized print culture,” as Tom Mole has identified this era (10), modes of defending it were increasingly subject to examination. Samuel Johnson had justified dueling on the basis that reputation was an equivalent property to a house (Boswell 4: 224), and his remark, out of context and flattening out his ambivalence, was widely promulgated in the early 1820s. This equivalency, by suggesting reputation was at once a legally protected property, a publicly valuable commodity, and a personal possession, established the three forms of adjudication—the courts, the press, and the duel—as inextricably interlaced. The courts made legal determinations, but without the press to authorize and disseminate them, they were ineffectually converted into principles or social norms; the press could represent a person’s character, but both the courts and the duel offered means of challenging that representation; and the duel, although putatively a private matter, required its result to be circulated (by trial, publication, or both) in order for it to counteract representations in the press. As the Eclectic’s running title suggests, this court case was, crucially if peripherally to the accusation of murder, about the status of dueling and the press.

The Press before the Trial

Like the fatal duel fought the year before between John Scott, the editor of the London, and Jonathan Henry Christie, a stand-in for Blackwood’s Magazine, the Stuart/Boswell duel was an extension of literary skirmishes, in this case waged initially between the Whig Scotsman and the Tory Beacon.[3] Both were recent periodicals, The Beacon having first appeared in January 1821 in response to The Scotsman, founded in 1817. Both had thoroughly imbibed, to Walter Scott’s dismay, the techniques of the more popular periodicals, especially Blackwood’s, of engaging in “personalities,” a practice which Kim Wheatley has identified as “a cultural preoccupation, frequently malicious, with the private lives of individuals in the public eye” (1). While both Beacon and Scotsman aimed at the other party as a political unit, each found such attacks particularly effective when deployed and figured as attacks on specific individuals, who then functioned metonymically for the degradedness of the party. In addition to articles on “Personality” (in numbers 31 and 32), The Beacon published “On Personality (From a Correspondent)”, which began:

If it is fair in party strife

To scrutinize a private life—

If cowardly scandal plays her game,

Against the best and greatest name, —

Shall any paltry blust’ring knave—

A democratic tyrant’s slave—

Talk big in public, yet defy

Truth’s searching, keen, discerning eye? (1: 35, 261; lines 1-8)

Responding to its own question with a “No” and an immediate counter-attack, the poem positions The Beacon as “Truth’s” champion, while “Learned Whigs / [should] Stick to that wit derived from wigs” (15-16). As Wheatley has shown, using “personalities” allowed journals to avail themselves of recognizable conventions (such as pack this doggerel poem) as well as to capitalize on readerly interest in individuals (1-15). At the same time, they were engaging in what Walter Scott saw as a dangerous game (he had himself engaged that game since his early disputes with Francis Jeffrey and the Edinburgh Review and his efforts in establishing the Quarterly; see Lockhart 2: 102-5 and Jeffrey, “Preface” vii-viii; see also Ina Ferris, “The Debut of The Edinburgh Review, 1802″). He wrote Archibald Constable in September 1821 that the “news from ![]() Edinburgh are very distressing for with the usual degree of party-spirit there has mixd of late a degree of violence which will be slaked I fear with nothing but blood. I expect daily to hear that someone is killd. The Scotsman and Beacon have much to answer for” (Grierson 7: 18).

Edinburgh are very distressing for with the usual degree of party-spirit there has mixd of late a degree of violence which will be slaked I fear with nothing but blood. I expect daily to hear that someone is killd. The Scotsman and Beacon have much to answer for” (Grierson 7: 18).

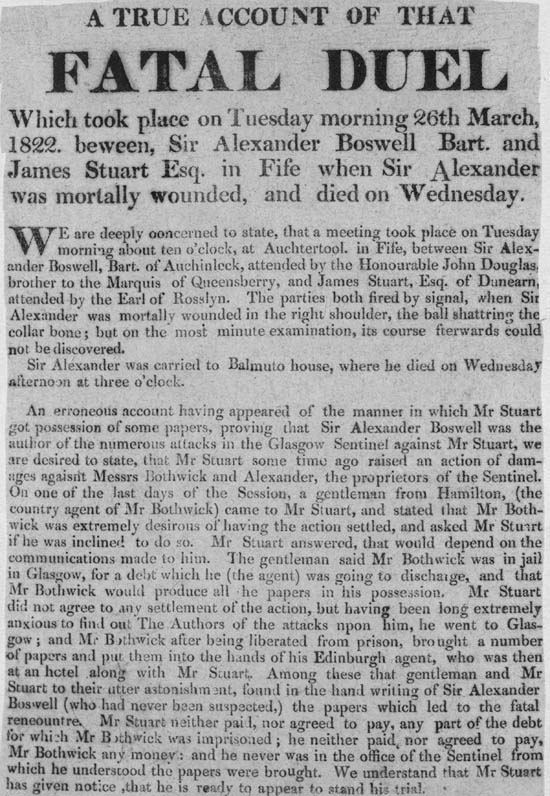

When The Beacon attacked James Stuart and fellow Whig James Gibson, they sued for “the injury done to their characters”; in consequence, The Beacon folded and its anonymous backers—who included both Walter Scott and William Rae, the primary prosecutor in the Stuart trial—were exposed and ridiculed.[4] Many in its editorial coterie, however, eventually reemerged with the Glasgow-based Sentinel. This new newspaper produced new attacks that were, according to the Trial I’s “Introduction,” “more personal and virulent” (4). When Stuart learned that Alexander Boswell was the author of several of these attacks, and most unforgivably, “Whig Song,”[5] a doggerel verse that rhymed “Stuart” to “fat-cow—art” (Trial II 7), he challenged Boswell. Boswell refused to apologize for the works—not because he wasn’t sorry (that question was moot throughout the pre-duel negotiations and the post-duel trial), but because to do so would acknowledge authorship, an unacceptable breach of journalistic anonymity.[6] Stuart was left with, he believed, only the option of proceeding with the duel, as the alternative would be to accept the characterization of cowardice. After Boswell apparently fired deliberately wide (Smith l-li), a common practice, Stuart “fired a pistol, on foot” for his first time and without aiming (Trial II 104).[7] His ball shattered Boswell’s collarbone, grievously damaged his spinal cord, and resulted in his death the following day.[8]

Figure 3: Broadside: “A True Account of that Fatal Duel” (courtesy of the National Library of Scotland)

After the duel and before the trial, the press weighed in on the events, trying at once to shape the discourse and to capitalize on public excitement. In the 16 April issue of the Kaleidoscope (2: 94), for example, about three weeks after the fatal encounter, the editorial voice made a proposal to its “Correspondents”:

A recent duel in the literary world has made the tickle point of honour a subject of very general conversation. We, therefore, take occasion to say that our columns are open to its discussion, without reference to the individual case of Mr. Stuart and Sir A. Boswell, which, if taken into consideration, might infringe upon political ground. (328)[9]

Offering potential contributors the reward of publication and free copies of two works, the magazine sought to capitalize on the widening discussion prompted by the duel, while generalizing it to the question of honor—and pointedly refusing to engage in personalities. A week later (2: 95), the magazine ran a brief historical article on duels (that concluded, quoting from Historical Anecdotes of Heraldry and Chivalry, with an account of a duel between an accusing dog and the man who murdered his master); the article emphasized their legal origins in Scandinavian law “in answer to the inexpiable accusation of cowardice” (333), the charge Stuart had leveled at Boswell for hiding behind authorial anonymity and that Boswell had made against Stuart in the “Whig Song.”

For the next several weeks, the Kaleidoscope published responses to its contest. On 30 April (2: 96), under its “Men and Manners” section on the front page, the Kaleidoscope published two letters, the first supporting the necessity of dueling as a general concept, even as it deplored particular outcomes, and the next opining against the utility of the practice. Both located the practice in medieval origins, the first declaring it “almost the only distinct practical memento of the feudal or chivalrous age now remaining” (337). Pointing to its deterrent effect on ill manners, slander, and “betray[ing] female innocence,” the writer argues that the criminal law lacked redress for “numberless moral evils and ways of offending” that the “laws of honour” could address. The next letter opens by declaring “True honour” as both a personal and social good, as it “puts a restraint on those passions which it deems incompatible with the good of society.” By contrast, “false honour” is a species of “pride” and is both “suspicious and irritable,” and this false honor carries the trace of the “barbarism of our ancestors” into the present to taint “the present enlightened state of society” (337-38). Conceding that there are some injuries “of an aggravated kind” that do not “come under the lash of the law,” the letter writer insists that they are in no way adequately addressed by duels: winning a duel, however much it may signal indignation, in no way invalidates an accusation, because the contest is devoid of any evidentiary function. Stripped of medieval divine intervention, duels become the effects of excessively heightened social manners in which “the slightest contradiction; nay, even a smile or a whisper” (338) can begin the train of accusations that terminates in a shooting. The writer concludes by questioning the effectiveness of dueling in producing “mannerly and well-accomplished gentlemen” because of the “restraint” to “their natural petulance” (338). Invoking a notion of statistical evidence, the writer suggests the desirability of knowing “how large a proportion of persons are influenced by this dread” and posits the “rage for dueling” in the “highly polished country” of Louis XIII’s ![]() France as countervailing evidence to its refining or deterring effect.

France as countervailing evidence to its refining or deterring effect.

By placing these letters side by side, the Kaleidoscope, subtitled a Literary and Scientific Mirror, enacted a public debate. The journal addressed at once the question of law as driven by evidence and its need for supplemental structures. Offering its own debating model as a more civilized form of disquisition, the magazine posed one solution in which the public press, rather than the private duel, functioned as the appropriate supplement to the law. Yet, by insisting that correspondents not mention the Stuart-Boswell duel in order to avoid inserting politics and personalities into the initial “competition,” the journal’s very solution, in effect pre-publication censorship, returned to the problem that had inspired the duel in the first place, namely, the difficulty in regulating a virulent press. Similarly, while a crucial justification for accepting a challenge lay in refuting the appearance of cowardice, in this case, Stuart had been accused of cowardice in a song in the Sentinel, and was making the charge on the basis of refuting that imputation. Thus, the structure of the duel mirrored the prior structure of accusations made in the periodicals.[10] Throughout the trial, both sides attempted to mobilize this symmetry for their own use.

The Trial

The trial, as was typical, began with the reading of the indictment, in the usual formal and somewhat antiquated language of that kind of document. The indictment set out two primary accusations: that Stuart had murdered Boswell in shooting him during their duel, and that he had, previous to the challenge, conspired to steal papers from the Sentinel, which ultimately led to his discovery of Boswell as the author of several journalistic attacks. This second accusation stemmed from a byzantine chain of events which Trial II recounts and John Chalmer’s Duel Personalities describes; Trial I, in part to remove ambivalence about Stuart’s role in acquiring the manuscripts, omits much of the testimony relative to this second accusation. For the purposes of this article, it is useful to highlight that Stuart’s acquisition of the papers revealing Boswell’s authorship needed to be defended on ethical rather than legal grounds (an acquittal for murder would make the lesser charge irrelevant) as it would preserve the chivalric character of the duel.

Henry Cockburn opened by responding to the indictment, not only to prepare the defense, but to secure his client’s honor in case “the trial on the part of the Public Prosecution break[s] down” before he had the opportunity to vindicate that honor in the course of the trial. In effect, declaring the legal outcome secondary to the task of recovering Stuart’s reputation, Cockburn centralized the matter of public reputation within the court, and thus made the court mirror the periodical culture in which reputation was both crucial and liable to be interfered with from a “variety of accidents” (Trial II 22). He extended this by a litotes, declaring that if he “were permitted to speak the sentiments of my client” (which he was not), he would “freely admit” that Boswell had “met with his death at the hands of the prisoner,” but declaring he was “not permitted to make here those candid and generous avowals which the prisoner would utter,” he called “on the public prosecutor to prove it” in order to “have the benefit of those explanatory circumstances of which we might otherwise be deprived” (24). This avowal at once declared Stuart’s admission (from an extra-legal perspective) of his actions and underscored his sympathy for Boswell; at the same time, by requiring proof, Cockburn insisted on the opportunity to affirm Stuart’s reputation, secondarily to defend it in the trial, and primarily, to reassert it in the public discourse and continue the reparation that the duel presumptively began. Cockburn then presented his provisional defense, recorded in eighteen pages in Trial II, delivering a long, detailed narrative. Trial I, interestingly, selected only one point in its redaction: Noting his objection was not “of a legal nature,” Cockburn pointed out that the indictment identified the defendant as “James Stuart Clerk to the Signet,” which was “not the title he deserved” because of his relation to “the Noble Families of Buchan, Erskine, and Moray, to which last,” his father “was presumptive heir to the honours of that ancient house” (11); “Whig Song” had identified Stuart as “But a Whig Signet clerk man” (Trial I, app. 34, st. 3). Admitting these errors were trivial, Cockburn nonetheless suggested they reflect “the mind and bearing” of the prosecutors.

Despite the legal irrelevance, Cockburn was trying to establish a pseudo-customary right to dueling, as well as to construct an equality between Stuart and Boswell, whose own family was titled. Cockburn further emphasized that the Earl of Moray, although “entitled to a seat on the bench with their Lordships, had preferred to take his seat at the bar, in order to manifest the respect and affection he bore towards his relative” (12). Dueling had been a privilege of the upper class, and indeed, an aristocrat could ignore a challenge from a commoner on the grounds that he had no standing to have issued it. (Prior to this duel, Stuart had been challenged by the printer of The Beacon, Duncan Stevenson, following a physical altercation in which each side claimed victory for himself and disgrace for the other; Stuart had maintained that the difference in their rank was sufficient grounds to refuse the challenge and Stevenson had retorted in print by declaring this evasion proved Stuart’s cowardice [Chalmers ch. 4].) With the shift from swords to pistols, the latter requiring less training, duels seemed to be spreading to the professional classes. A case in point was the meeting between Francis Jeffrey and Thomas Moore, which Lord Byron rendered farcical in his English Bards and Scotch Reviewers. Similarly, Byron—an aristocrat who presented himself as always ready to give satisfaction and yet managed never to have to—was chased by Thomas Moore’s challenge for months. The end results of the duel and the non-duel were that Moore became close friends with both Jeffrey and Byron. Jerome Christensen proposes that the conflict between Byron and Jeffrey (over the Edinburgh Review’s attack on Byron’s Hours of Idleness) “became a contest to determine how the conflict would be characterized, whether as a legal struggle between plaintiff and defendant that would observe judicial protocol . . . or as a duel that would elaborate its punctilio . . . beyond the jurisdiction of burgher and king,” while, as Christensen punningly notes, both “metaphors had their appeal, . . . [n]either fits” (xix-xx), in part because, in the modern conceptualization in which gentlemen, and not just aristocrats, participated in the extra-legal construct of the duel, dueling was inseparably enmeshed in the space of the juridical court. Despite (and indeed embedded in) such comic effects as Byron’s English Bards and Scotch Reviewers and Lord Ellenborough’s exasperated response, in 1812, to modern challenges that “Really it was high time to stop this spurious chivalry of the compting house and the counter” (qtd. in Andrews 433), the aristocratic justification for dueling remains visible, and Cockburn’s immediate response to the indictment, insisting on Stuart’s rank, underscores the role of dueling in the conceptualization of masculine individualism as it is shadowed by aristocratic privilege.[11]

Figure 4: James Stuart of Dunearn (1775-1849), Duellist and Pamphleteer (courtesy of the Scottish National Portrait Gallery)

The first witness called by the prosecution, Stuart’s second, the Earl of Rosslyn, described his efforts to avert the duel while simultaneously negotiating its terms. He suggested to John Douglas, Boswell’s second, that, if Boswell “should treat the song as a very bad joke on his part, and one for which he was sorry, and that he had no wish . . . to reflect on Mr. Stuart’s courage” (Trial I 14), the matter could be ended; Douglas, however, averred he “had no hopes that Sir Alexander would say any such thing.” This particular exchange impinges on the question of the intentionality in satires. As Kim Wheatley has observed, the penchant for exaggeration and satire was a staple of the hugely successful Blackwood’s and the prominent quarterlies before it (15), and the Sentinel was following in that success. Boswell had no need to form any intentionality whatsoever regarding Stuart’s courage—and there is no evidence he had any opinion about it—in composing the song; rather, he was looking for rhetorical effect. Rosslyn’s account would not seem to influence the fundamental law that, as an article in the Edinburgh Review described it, “a duel, where one is killed, is a capital offence in all who take part . . . and this without the least regard to what are termed the rules of honour, which all lawyers affect to know nothing of.” The article continues, however, “Yet this law is a mere dead letter” because of both reluctant prosecutors, and more significantly, “the feelings of juries” (Jeffrey, “Art. V” 74). It is to these feelings that Rosslyn addresses his narrative, constructing the events surrounding the duel as governed by laws of honor and fairness and consequently necessity.

Francis Jeffrey himself, as one of five “Counsels for the Prisoner” and editor of the Edinburgh Review (and someone who had been demeaned in one of the articles attributed to Boswell), structured his examinations of witnesses and closing arguments to demonstrate that Boswell had indisputably written the offensive papers, that Stuart was remorseful about Boswell’s death, and that Stuart felt he had had no choice but to act as he did. Jeffrey questioned three witnesses who saw Stuart in France after he fled there. Thomas Allan’s testimony about delivering the news of Boswell’s death to Stuart is summarized in the Trial I account:

At this intelligence he burst into tears and was much agitated—Witness [i.e. Allan] remarked to him, that the affair was forced on him, he said “true, but remember his wife and family.” Witness was with him about a fortnight, during which Mr Stuart’s mind often reverted to the subject, and was often absorbed in thought. (27)

Another witness, John Clerk, similarly reported that Stuart “appeared to be very much affected.” This remorse could fit into a narrative of guilt, as a sign of recognizing wrong-doing, but here it functions to sustain Stuart’s character. Jeffrey called further witnesses, including Dr. Coventry, who vouched for Stuart’s consistent character in “public and private society,” calling him as “possessed of the best qualities” and asserting that “his behavior [was] very insinuating, and always disposed to settle quarrels” (Trial I 27-28). Asked by Jeffrey, “Is he a safe man to joke or tease a little,” Dr. Coventry replied, “Perfectly safe” (Trial II 116). The leading question reminded the audience and jury that a gentleman must enforce limits on how much teasing he will endure. Lord Kinnidder (William Erskine) declared he “never knew a more perfectly good tempered and more amiable man, nor a safer companion,” despite their “differ[ing] very decidedly in politics” (Trial I 29). By presenting a consistent character, the defense establisheed both the sense that Stuart felt compelled to the duel and underscored the libelous nature of Boswell’s representations.

The final arguments were delivered in the early hours of the morning; the Lord Advocate, in “a short, distinct speech” observed that it was “his bounden duty to bring this case to trial,” a phrasing signaling his own personal reluctance yet insisting on the law’s clarity: dueling is “in noways sanctioned by our law” regardless of “however fair the duel might have been,” and, further, “self-defence could not be urged as a defence against the charge.” His strategy was to avoid the appearance of “personalities” within the court and instead to ground the prosecution on unequivocal law. Jeffrey, as if to put time between the Lord Advocate’s speech and the deliberation, “made a very long argumentative speech—which . . . it is impossible for us to attempt to report—he spoke for nearly three hours” (Trial I 30). That the length alone, rather than the contents, is an adequate presentation of the speech suggests (as was intimated in the “Introduction” to Trial I) that the narrative derived from the accounts of the witnesses told the substantial story, and that its reiteration was unnecessary for the careful reader who will have entered into the anguished feelings of the defendant and his supporters. The longer Trial II, by contrast, presented the speech at the length of 30 pages; within it, Jeffrey shapes a cultural history of the duel, its code of honor, and its role in the formation of modern masculinity and manners.

Jeffrey understood the rhetorical force in adjusting the jury from adjudicators of fact to public representatives, situating them in ways parallel to reviewers. The function of the trial, Jeffrey noted near the outset, was “above all, . . . that full disclosure of the truth, for which, if it answered no other end, this public trial by jury ought to be for ever immortal” (Trial II 135). His use of the language of canonical aesthetics located the jurors as readers of a narrative, the one offered by the witnesses (which Trial I deemed adequate without Jeffrey’s intercession). He offered a typical “Edinburgh Review” of the case, noting that the “evidence” had been “all perfectly harmonious and consistent throughout” as to the defendant’s “character”; this obscured moments in the trial where contrary representations were subsumed under interpretive abstractions to produce that consistency. Shifting to a contemporary depth psychology, Jeffrey laid stress on the indictment’s archaic language that the prisoner “having conceived malice against the late Sir Alexander Boswell” chose to “wickedly and maliciously” shoot him (135-36). He was here confounding a disposition—the malice against Boswell—with a description of the act of murder, which, as the indictment specifies, was “a crime of a heinous nature” (Trial II 1). By doing so, Jeffrey intended to align Stuart’s act with self-defense (a ground for acquittal explicitly excluded from those available to a dueler at Common Law) without claiming it was self-defense. Jeffrey knew he was eliding the common usage of “malice” with its both technical and archaic sense that persisted in indictments as part of their ritualistic form. In 1789, the re-issued Report of Diverse Cases, by John Kelyng and re-edited by G. J. Browne, distinguished hatred, “a Rancour fixed and settled in the Mind” from Malice, a “Design formed of doing mischief to another” (126-27). Stuart was well aware of the illegality of the duel, and so, despite the absence of any personal hatred toward Boswell, that legally constituted malice. This specific play on meaning was characteristic of Jeffrey’s defense, in which he argued for the social utility of dueling by carefully intermixing archaic and modern perceptions. Although, as Andrews points out, the “modern duel of honour was an import from the Continent” and not a direct descendent from the “judicial and chivalric duels [that] were publicly sanctioned trials by combat” (409-10), in conflating them here, Jeffrey was acting on a popular construction of continuity, one exploited by Walter Scott and other novelists.

Jeffrey described dueling as having “superseded the guilt and atrocity of private assassination” (138), and therefore, despite its illegality, serving a critical legal function. Jeffrey’s paradoxical conclusion was that the barbarism of dueling produced the gentility of the professional class. Unwilling to claim that in ![]() Scotland, suppressing dueling would lead to a return of private assassination, he claimed instead that it would lead to “to private and secret meetings held without witnesses, and without the means afforded to the parties of guarding against unfairness, or, what is as distressing and painful, the suspicion of it where it did not exist.” That is, the suppression of dueling would lead to the inability to adjudicate duels for fairness. By this reasoning, Jeffrey had shifted the jurisdiction from the law to the code of honor by which duels allegedly proceed, and further, which their popular representation underscored. The code became a form of contract by which both gentlemanliness and masculinity were constituted; Cronin points out that to John Scott, in the earlier duel, and James Stuart, having each “been publicly branded as cowards,” a duel “must have seemed” as if it were “the only way available” of “ratifying their masculinity” (15). In Jeffrey’s argument, the courts, therefore, became the horizon of enforcement of that code; Jeffrey declared that the only cases of dueling in which juries returned guilty verdicts were when the prosecution could demonstrate the duel had been unfair on its own terms. Having insisted upon the necessity of dueling as a social organizer, Jeffrey deduced that an individual duel, then, is a necessary product of that system, and not the fault of the “unfortunate individual” caught within it. This is constructing a narrative necessity based at once on the contemporary notion of the gentleman and the palimpsest of the chivalric knight as his precursor. Where once, in medieval wager of battle, the duel produced the truth of an accusation, it now produces the truth of character.

Scotland, suppressing dueling would lead to a return of private assassination, he claimed instead that it would lead to “to private and secret meetings held without witnesses, and without the means afforded to the parties of guarding against unfairness, or, what is as distressing and painful, the suspicion of it where it did not exist.” That is, the suppression of dueling would lead to the inability to adjudicate duels for fairness. By this reasoning, Jeffrey had shifted the jurisdiction from the law to the code of honor by which duels allegedly proceed, and further, which their popular representation underscored. The code became a form of contract by which both gentlemanliness and masculinity were constituted; Cronin points out that to John Scott, in the earlier duel, and James Stuart, having each “been publicly branded as cowards,” a duel “must have seemed” as if it were “the only way available” of “ratifying their masculinity” (15). In Jeffrey’s argument, the courts, therefore, became the horizon of enforcement of that code; Jeffrey declared that the only cases of dueling in which juries returned guilty verdicts were when the prosecution could demonstrate the duel had been unfair on its own terms. Having insisted upon the necessity of dueling as a social organizer, Jeffrey deduced that an individual duel, then, is a necessary product of that system, and not the fault of the “unfortunate individual” caught within it. This is constructing a narrative necessity based at once on the contemporary notion of the gentleman and the palimpsest of the chivalric knight as his precursor. Where once, in medieval wager of battle, the duel produced the truth of an accusation, it now produces the truth of character.

Arguing next to establish the lawfulness of dueling, Jeffrey offered his first authority within a genealogy in which this duel was the final term: Samuel Johnson defended dueling and James “Boswell concurred” and “from what we have heard today, it appears that his son inherited these opinions” (Trial II 139).[12] Jeffrey knew Johnson lacked legal authority and fused his literary authority with the law. Johnson maintained that the “justification” for dueling that equated reputation with property was “only applicable to a person who receives an affront. All mankind must condemn the aggressor” (Trial II 140; J. Boswell 2: 183, “receives” italicized in latter, which was the edition from which Jeffrey was quoting). The defense witnesses had been carefully arrayed to make Boswell, by virtue of having published “Whig Song” the “aggressor,” and so the sequence of evidence anticipated Jeffrey’s deployment of Johnson. Given the long strand of accusations and counter-accusations, however, who the aggressor was, even whether there was an aggressor, and if so whether that aggressor was an individual or corporation, were themselves narrativized questions in the trial, capable of alternative presentations.[13]

After Jeffrey concluded his remarks, the Lord Justice Clerk addressed what must have been an exhausted jury, declaring they had “paid such devoted attention to the evidence” that he would not rehearse it; rather, he used legal authorities—Sir George Mackenzie and Baron Hume—to reiterate that “killing in a Duel is murder” (Trial I 31). He acknowledged, however (a wink to the anticipated verdict), that Hume states “in later times, some Juries had taken upon them to deliver verdicts of not guilty in such cases: but . . . that such decisions were not in conformity to the strict law of Scotland” (31). Emphasizing the strictness, which echoed the strict laws of honor that had so palpably driven Stuart’s own understanding, offered the jury a route to leniency based on prior juries. Further, the Justice reminded the jury to “keep distinctly in view the nature of the offers made by Mr Stuart”—that Boswell either disclaimed authorship or apologized for the satires—and that “Sir Alexander unfortunately would not consent to either of these proposals” (31-32). (The events are characterized as “unfortunate” five times in Trial I, and the term recurs more than 30 times in Trial II, as if to render those events beyond Stuart’s control.) The judge next recounted the gist of the character witnesses, claiming “in the whole course of his practice he never had heard higher, or more distinct and discriminant praise bestowed on any character” (32). The “learned judge” then “begged it to be distinctly understood” that he was not giving “countenance to the crime of dueling,” but “lamented” that the “public groaned under the lamentable licentiousness of the press,” a move equating the public—and so the jurors—with Stuart, much beleaguered by the press, and setting out as a cause and effect the licentiousness of the press and the evils of dueling.

As was a typical practice during the time, the jury deliberated without leaving the courtroom, and after “a few minutes” its “chancellor delivered an unanimous verdict of—Not Guilty,” a verdict “received with loud cheers from without the doors and with marked approbation from those within” (Trial I 32). In addition to the two published reports, nearly a dozen periodicals noticed the trial at varying lengths, many drawing liberally from the published accounts, and adding embellishments that directed readerly sympathy.[14] The Edinburgh Chronicle recounts the trial, and, after noting that the “populace” awaiting the verdict outside was “extremely noisy” and exhibited “much cheering” on its announcement, imaginatively follows Stuart through the streets to his home, where a crowd rushed to greet him. Stuart “earnestly entreated them” for silence and “with this they complied, but insisted on giving three muffled cheers; and, after waving their hats, retired in silence” (“British Chronicle” 134). This final tableau is reconciliatory, an image of high spirits expressed in moderation, spent out with an orderly, muted, ritualized practice, as if the process of duel and trial has been salutary, however unfortunate. This image, given Stuart’s Whig alliance and the synonymous use of “populace” and “crowd,” is an image of political responsibility, a contrast to the periodical confusions and excesses with which the duel began—and indeed, which would erupt again soon.

published September 2015

HOW TO CITE THIS BRANCH ENTRY (MLA format)

Schoenfield, Mark. “The Trial of James Stuart (1822): ‘Abuse of the Press, and Duelling.'” BRANCH: Britain, Representation and Nineteenth-Century History. Ed. Dino Franco Felluga. Extension of Romanticism and Victorianism on the Net. Web. [Here, add your last date of access to BRANCH].

WORKS CITED

Andrews, Donna. “The Code of Honour and Its Critics: The Opposition to Duelling in England, 1700-1850.” Social History 5 (Oct. 1980): 409-34. JSTOR. Web. 14 Feb. 2015.

“Art. VI. The Trial of James Stuart, Esq. younger of Dunearn, before the High court of Justiciary at Edinburgh, on Monday, June 10, 1822. Taken in short-hand, and prepared under the Direction of his friends.” Eclectic Review 18 (Aug. 1822): 170-82. British Periodicals. Web. 14 Feb. 2015.

Austen, Jane. Pride and Prejudice. 1813. Ed. Tony Tanner. New York: Penguin, 1972. Print.

Beacon, The. Duncan Stevenson, printer. Edinburgh, 1821.

Boswell, James. The Life of Samuel Johnson, LL.D. 1791. 5th Edition, Revised and Augmented. 4 vols. London: Cadell and Davis, 1807. Google Books. Web. 10 Aug. 2015.

Brewton, Vince. “‘He to Defend: I to Punish’: Silence and the Duel in Sense and Sensibility” Persuasions: The Jane Austen Journal On-Line 23 (2001): 78-89. Web. 4 Apr. 2015.

“British Chronicle.” Edinburgh Magazine and Literary Miscellany 11 (Jul. 1822): 125-34. British Periodicals. Web. 14 Feb. 2015.

British Code of Duel: A Reference to the Laws of Honour, and the Character of Gentleman. 1824. Surrey: Richmond, 1971. Print.

Chalmers, John. Duel Personalities: James Stuart versus Sir Alexander Boswell. Edinburgh: Newbattle, 2014. Kindle.

“Charge to the Jury.” The Calcutta Journal of Politics and General Literature 6.308 (24 Dec. 1822): 737-39. Ed. James Silk Buckingham. British Periodicals. Web. 14 Feb. 2015.

Christensen, Jerome. Lord Byron’s Strength: Romantic Writing and Commercial Society. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins UP, 1993. Print.

Cline, Clarence Lee. The Fate of Cassandra: The Newspaper War of 1821-22 and Sir Walter Scott. Austin: U of Texas P, 1971. Print.

Cronin, Richard. Paper Pellets: British Literary Culture after Waterloo. New York: Oxford UP, 2010. Print.

Douglas, David, ed. Familiar Letters of Walter Scott. 2 vols. Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1894. Google Books. Web. 14 Feb. 2015.

Grierson, H. J. C., The Letters of Sir Walter Scott. 13 vols. London: Constable & Co, 1934. The Letters of Walter Scott: E-Text. Edinburgh University Library. Web. 14 Feb. 2015.

Jeffrey, Francis. Preface. Contributions to the Edinburgh Review. Boston: Phillips, Sampson, and Co, 1856. Google Books. Web. 1 Apr. 2015.

Jeffrey, Francis, ed. “Art V. A Treatise on the Offence of Libel . . . By John George . . .” Edinburgh Review 22: (Oct. 1813): 72-88. Google Books. Web. 14 Feb 2015.

Johnson, John. Typographia, Or the Printers’ Instructor . . . with An Elucidation of Every Subject Connected with the Art. 2 vols. London: Longman, 1824. Google Books. Web. 14 Feb. 2015.

Jones, Leonidas. “The Scott-Christie Duel.” Texas Studies in Literature and Language 12.4 (1971) 605-29. JSTOR. Web. 14 Feb. 2015.

Kaleidoscope; or Literary and Scientific Mirror. 1818-1831. Ed. Egerton Smith. British Periodicals. Web. 14 Feb. 2015.

Kelyng, John. Report of Divers Cases in Pleas of the Crown . . . In the reign of the Late King Charles II. 1708. Ed. G. J. Brown. Dublin: Byrne, 1789. Google Books. Web. 14 Feb. 2015.

Lang, Andrew. The Life and Letters of John Gibson Lockhart. 2 vols. London: John C. Nimmo, 1897. Google Books. Web. 14 Feb. 2015.

Lockhart, John Gibson. Memoirs of the Life of Sir Walter Scott. 5 vols. Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1901. Google Books. Web. 1 Apr. 2015.

McCracken-Flesher, Caroline. Possible Scotlands: Walter Scott and the Story of Tomorrow. Oxford: Oxford UP, 2005. Print.

Mole, Tom. Byron’s Romantic Celebrity: Industrial Culture and the Hermeneutics of Intimacy. New York: Palgrave, 2007. Print.

“Newspaper Press of Scotland.” Fraser’s Magazine for Town and Country 17 (May 1838): 559-71. British Periodicals. Web. 14 Feb. 2015.

Radcliffe, David Hill. “Blackwood’s Magazine, the London Magazine, and the Scott-Christie Duel.” Lord Byron and his Times. Virginia Tech. Web. 1 Apr. 2015.

Sales, Roger. John Clare: A Literary Life. New York: Palgrave, 2002. Print.

Smith, Egerton, Ed. The Kaleidoscope; or Literary and Scientific Mirror. 1818-1831. British Periodicals. Web. 14 Feb. 2015.

Smith, Robert Howie. “Memoir.” Introduction. Poetical Works of Alexander Boswell. By Alexander Boswell. Ed. Robert Howie Smith. Glasgow: Maurice Ogle and Co, 1871. xxi-lxi. Google Books. Web. 14 Feb. 2015.

[Trial I] Trial of James Stuart, Esq., Younger of Dunearn Before the High Court of Justiciary on Monday the 10th day of June 1822 for the Mirder of Sir Alexander Boswell, of Auchinleck, Bart., In a Duel on the 24th Day of March Last. Edinburgh: J Dick & Co, 1822. Google Books. Web. 14 Feb. 2015.

[Trial II] Trial of James Stuart, Esq. Younger of Dunearn before the High Court of Justiciary at Edinburgh on Monday, June 10, 1822. Taken in Short Hand, With an Appendix of Documents. Edinburgh: Constable and Co., 1822. Google Books. Web. 14 Feb. 2015.

“True Account of that Fatal Duel.” Broadside. The Word on the Street. National Library of Scotland, 2004. Web. 18 Apr. 2015.

Wheatley, Kim. Romantic Feuds: Transcending the “Age of Personality.” Burlington: Ashgate, 2013. Print.

“Whole Particulars of the Trial of Mr James Stuart.” Broadside. The Word on the Street. National Library of Scotland, 2004. Web. 18 Apr. 2015.

ENDNOTES

[1] The shorter account is interesting in terms of its choices to abridge, while the longer account contains preliminary papers and more details that give a more extensive account of the legal process. John Chalmers, in Duel Personalities: James Stuart versus Sir Alexander Boswell, offers the most extensive historical account of both the trial and the duel, as well as their political and social contexts; the publication details are taken from his account (ch. 7). To describe the trial, Chalmers draws on, in addition to the two published accounts, Henry Cockburn’s manuscripts (held at the National Library of Scotland) related to his trial preparation. I follow Chalmers’s method in identifying the earlier and shorter account as Trial I and the longer as Trial II; citations to Trial I usually have analogues in Trial II. The broadside titled “The Whole Particulars of the Trial of Mr James Stuart” is available at the Word on the Street website.

[2] Mr. Bennet had earlier “accepted the challenge” of Mr. Collins to backgammon, in a comic foreshadowing of the duel Mrs. Bennet fears (Austen 310). In Sense and Sensibility, Colonel Brandon explains a duel, which ended harmlessly, was fought by him and Willoughby. Vince Brewton contends the duel “reveal[s] an otherwise undisclosed depth of masculine rivalry over the possession of women” in the novel (84).

[3] Leonidas Jones provides a detailed account of the Scott-Christie duel, and Richard Cronin (1-13) describes and connects the politics of both duels. Cronin observes that “Both duels were a product of a sudden and significant expansion of the print industry, as a consequence of which those like John Scott and James Stuart who found themselves involved in journalistic quarrels were unsure whether the dispute was public or personal” (15). David Hill Radcliffe provides a chronology of the Scott/Christie duel that has to links to relevant contemporary documents. Roger Sales offers an account of the Scott duel (30-39) that demonstrates John Clare’s allegiance to Scott as “a missing link in much Clare criticism” (39).

[4] Caroline McCracken-Flesher contends that Walter Scott, as a “silent, non-circulating sponsor” of The Beacon, became “implicated in the utterances of others” when James Gibson responded to attacks by that magazine and “traced fiscal responsibility” (63) for the journal to fifteen Tories, the most literarily prominent being Scott, who was therefore imputed authorship to articles he denied ever reading. Despite his roles in backing and writing for numerous Tory magazines, Scott was alarmed by the hydra he had helped create. After Boswell was shot but not yet dead, he wrote Lockhart (who surely felt the echoes to John Scott’s death), “I sincerely hope that this catastrophe will end the species of personal satire and abuse which has crept into our political discussions; the lives of brave and good citizens were given them for other purposes than to mingle in such unworthy affrays” (Douglas 2: 137). Lockhart, in the letter conveying the news of Boswell’s death, thanked Scott “for the advice which kept me from having any hand in all these newspaper skirmishes,” a claim that does not account for the repeated magazine skirmishes he did engage (2: 138). Scott was acutely aware of how public notice transformed identity; he had warned Lockhart, when the latter had attacked a political opponent, “If M’Cullock were to parade you on the score of Stanza XIII, I do not see how you could decline his meeting, as you make the man your equal (ad hoc, I mean), when you condescend to insult him by name” (Lang 1: 241; qtd. in Jones 607.) Scott saw the skirmishes of the Beacon and the Sentinel as occurring within the paradigm constructed by Blackwood’s Magazine, and played out earlier in the Christie-John Scott duel that embodied the confrontation between Blackwood’s and the London.

[5] Stuart’s second, Lord Rosslyn, noted that if Boswell had shown contrition over “Whig Song” (or even denied authorship despite the manuscript evidence), Stuart could have let the rest go (Trial II 47). In part, Stuart’s focus on Boswell was because his authorship had been accidentally discovered even though other authors were implied by the “week after week” during which Stuart and Gibson “were to be held up to ridicule and to be the subjects of satirical verses and squibs” published with maintained anonymity in The Beacon (Cline 13).

[6] This practice of journalistic anonymity was widely debated and vexed, and ranged from a well-kept to an open secret, from a practice defined by a corporate ethos to a scurrilous evasion. By the time of the challenge, Boswell’s anonymity was completely conventional, as Kim Wheatley points out was often the case with anonymous publication (6-7), because Stuart had the proof of authorship by his possession of the manuscripts, and Boswell knew this. The stated policy of The Beacon was to disclose, upon request of an attacked individual, the author of an offending article, provided the request was accompanied by an agreement not to seek legal reparations—leaving, however, the option of a duel available.

[7] A witness, James Gibson, described Stuart’s comment after the shooting: “He said he had taken no aim. He wished to God he had taken an aim, for, if he had, he was certain he would have missed him” (Trial II 104).

[8] Cockburn describes Boswell as a “‘half friend’ and distant relative” of Stuart, who was “astonished” to learn of Boswell’s authorship (Cline 31, quoting Trial II 34). Cline suggests that Boswell’s motives were “two fold: the virulence of Tory-Whig politics at the time” and Boswell’s “dark suspicion” that “Stuart was the author of an anonymous attack on him in The Scotsman” (31).

[9] Avoiding “any public news, intelligence or occurences, or any remarks or observations thereon” (Johnson 2: 574) as loosely as that category of “news” was construed, helped the Kaleidoscope steer clear of both the Newspaper Stamp Duties Act (60 Geo III cap. 9; one of the “Six Acts” of 1819) and any entanglement in the series of libel actions that surrounded the duel.

[10] The Kaleidoscope did not cover the trial, but in its 25 June issue, two weeks after the acquittal, republished the letter from Boswell, “adduced by the defence,” to Maconochie asking him to serve as Boswell’s second; the letter is full of delicacy and fairness, and in the retrospect of Boswell’s death, elegiac (“The Late Duel” 2: 104, 405-06). Having published a number of contributions on dueling, it did not declare a winner to its competition until in its 5 November 1822, issue (3: 123); in that issue, it published a letter titled “Prize Essay on Duelling,” which observed that the Kaleidoscope seems to have “awarded the bays to us all, good, bad, and indifferent” (144). The author then notes his early contribution “in favour of dueling” was adapted by Francis Jeffrey, “the supreme arbiter in the world of letters” in “his admirable defence of Mr. Stuart,” and on this ground, claims the prize and disavows his earlier assertion of not seeking it. Playing on the issues of anonymity and handwriting identification that propelled the duel and featured in the trial, the Kaleidoscope, in its “To Correspondents” in the adjacent column awards this unnamed essayist the prize, announcing, “We shall easily recognize the hand-writing” to “be that of an old and most welcome correspondent” (144).

[11] Cockburn ends his pre-trial written response to the indictment by averring Stuart’s being “satisfied that, if he be tried by his peers, he cannot be found guilty of any crime” (Trial II 20). The jurors listed include “Sir Alexander Charles Maitlan Gibson of Cliftonhall, Bart,” “Sir John Hope of Craighall, Bart.” and “Sir James Dalyell of Binne, Bart,” as well as a clothier and ironmonger from Edinburgh and a wine-merchant and merchant from Leith (Trial I 13; Trial II 44). By Scottish law at the time, the presiding judge selected fifteen jurors from forty-five available to him in the Assize. All forty-five were present during (and addressed as a collective in) Cockburn’s speech, and the fifteen jurors were selected after the indictment was modified and accepted by the court.

[12] Jeffrey is reading Boswell’s Life of Johnson somewhat selectively. Boswell had written in a footnote:

I think it necessary to caution my readers against concluding that in this or any other conversation of Dr. Johnson, they have his serious and deliberate opinion on the subject of dueling. In my Journal of a Tour to the Hebrides, . . . He fairly owned he could not explain the rationality of dueling.” (Boswell 4: 224)

While citing the text to which this footnote is appended (Trial II 146), Jeffrey omits Boswell’s qualification.

[13] To postulate an originary moment was a key strategy for the defense, but any interpretation of the key offensive word, “cow—art” as coward (which was disputable and denied by Stuart) rather than “cowherd” (which was a factual claim) depended on prior knowledge of Stuart’s encounter with Stevenson. Fraser’s Magazine, in describing “The Newspaper Press of Scotland” (May 1838), declares the word “did not allude to his courage, but meant cow-herd’ and was inserted merely for ‘the sake of metre’” (“Newspaper Press” 571).

[14] The Edinburgh Annual Register for 1822 (Edinburgh, 1824), overseen by Walter Scott, had a fifty-nine-page summary of the trial. This issue also contained an account of the libel trial against The Beacon that resulted in its restructuring and relocating as The Sentinel, a crucial event in the lead-up to the duel. The Calcutta reprinted the “Charge to the Jury” from The Scotsman, which was “so convinced of its doing honour to the Judge, to the law, and to human nature, that, with the exception of the statement of law authorities, we now give it at length” (737). Omitting the legal authorities that emphasized that to kill in a duel was murder, the statement does “honour” by insisting on honor itself as the measure for adjudication (737).