Abstract

The “debate” over evolution between T. H. Huxley and Bishop Samuel Wilberforce at the 1860 meeting of the British Association for the Advancement of Science in Oxford is an iconic story in the history of evolution and, indeed, in the history of the conflict between science and religion, second only to Galileo’s troubles with the Vatican. Huxley, the traditional account has it, vanquished Wilberforce by responding to an insulting question about his own ancestry with a masterful rejoinder that exposed the Bishop’s ignorance of science and ungentlemanly behavior. Historians have shown that this traditional account is biased and distorted, a construction many years after the fact by the Darwinians and their allies, yet it continues to live on, even in literary studies. Reconstructing the Huxley-Wilberforce encounter, the contexts in which it took place and what is and is not known about it, yields an understanding of the relationship between religion and science in the Victorian period that is fuller and more complex than the traditional “conflict” model.

There was no such thing as the Huxley-Wilberforce debate, and this is an essay about it.[1]

The 1860 meeting of the British Association for the Advancement of Science opened in ![]() Oxford in late June. It was the first gathering of the BAAS since the publication of Charles Darwin’s On the Origin of Species the previous November. Darwin’s book remained the talk of the scientific community and was generating considerable controversy among the wider public. As the traditional account has it, on Saturday, 30 June, Samuel Wilberforce (Fig. 1), the powerful Bishop of Oxford, debated Thomas Henry Huxley (Fig. 2), Darwin’s friend and chief scientific defender. Wilberforce, known as “Soapy Sam” for his smoothness and rhetorical slipperiness in debate, offered a lengthy denunciation of Darwin’s theory, ridiculing it and declaring it to be at odds with Scripture. As he closed his remarks, Wilberforce turned to Huxley and sneeringly asked him if it was through his grandfather or grandmother that he claimed descent from apes. The audience cheered. Huxley turned to the man seated next to him and whispered, “The Lord hath delivered him into mine hands.” Rising to his feet, Huxley responded that he would rather have an ape for an ancestor than a bishop who distorted the truth. This rebuke brought the audience around to Huxley’s side, their laughter and roars of approval greater than for Wilberforce’s jibe. Huxley had won an audience mostly hostile to evolution to his side. It was a turning point not merely in the fortunes of Darwinism but in the history of science, the day when Darwin’s theory earned the right to a fair hearing and science threw off the shackles of religious authority.

Oxford in late June. It was the first gathering of the BAAS since the publication of Charles Darwin’s On the Origin of Species the previous November. Darwin’s book remained the talk of the scientific community and was generating considerable controversy among the wider public. As the traditional account has it, on Saturday, 30 June, Samuel Wilberforce (Fig. 1), the powerful Bishop of Oxford, debated Thomas Henry Huxley (Fig. 2), Darwin’s friend and chief scientific defender. Wilberforce, known as “Soapy Sam” for his smoothness and rhetorical slipperiness in debate, offered a lengthy denunciation of Darwin’s theory, ridiculing it and declaring it to be at odds with Scripture. As he closed his remarks, Wilberforce turned to Huxley and sneeringly asked him if it was through his grandfather or grandmother that he claimed descent from apes. The audience cheered. Huxley turned to the man seated next to him and whispered, “The Lord hath delivered him into mine hands.” Rising to his feet, Huxley responded that he would rather have an ape for an ancestor than a bishop who distorted the truth. This rebuke brought the audience around to Huxley’s side, their laughter and roars of approval greater than for Wilberforce’s jibe. Huxley had won an audience mostly hostile to evolution to his side. It was a turning point not merely in the fortunes of Darwinism but in the history of science, the day when Darwin’s theory earned the right to a fair hearing and science threw off the shackles of religious authority.

The only problem with this account of that June day in Oxford is that most of it is tendentious and some of it simply untrue. Since at least the 1980s, historians have widely regarded the traditional account of that day as a myth or legend.[1] The exchange between Huxley and Wilberforce, these revisionist accounts have shown, barely registered on public consciousness at the time, mainly because press coverage of the event was so limited. Nor was the exchange part of a formal debate, instead arising more or less spontaneously during a discussion that included a number of other participants following another speaker’s paper. Wilberforce’s case against Darwinism was made primarily on scientific and philosophical, not religious, grounds, and some thought botanist Joseph Hooker, another friend and ally of Darwin’s, the more effective defender of the evolutionary faith. The exact forms of Wilberforce’s question and Huxley’s retort are uncertain, and the most detailed contemporary journalistic account of their exchange, in the Athenaeum, mentioned neither. Opinions of participants and observers were divided as to who could claim victory, and on what grounds. One of the few contemporary journalistic accounts of the exchange even cast the event as a sign of toleration, not hostility, between science and religion.

The codification of the legendary account of the Huxley-Wilberforce “debate,” historians have shown, occurred more than twenty years after the event, in the 1880s and 90s. It was a construction, almost exclusively, of the Darwinians and their allies. In particular, it was the work of Darwin’s son, Francis (Fig. 3), himself a botanist, and Huxley’s son, Leonard, in their respective Life and Letters volumes of their fathers and reinforced in Leonard Huxley’s Life and Letters of Hooker. For the Life and Letters of Charles Darwin in 1887, Francis Darwin drew on a variety of sources: contemporary accounts in his father’s correspondence, the lengthy summary published a week later in the Athenaeum (which contained no reference to Wilberforce’s jibe and Huxley’s rejoinder), and versions from among the flurry of reminiscences that followed his father’s death in 1882 and from others that he solicited.

Leonard Huxley borrowed from Francis Darwin’s sources and solicited several new reminiscences from eyewitnesses. These sources, however, were overwhelmingly from Darwinian partisans, and most were drawn from recollections made twenty to forty years after the fact. While those sources shouldn’t be rejected on those grounds, historians have come to recognize that the story they tell is heavily biased and sometimes contradicted by other contemporary evidence. The story told by Francis Darwin and Leonard Huxley was, not surprisingly, the story the Darwinians had long told amongst themselves, in which they were the clear victors and natural science stood up to religious ignorance and obscurantism. Once ensconced in the three Life and Letters, this version became the established account, repeated and recycled, often with additional embellishments. A vivid case in point was William Irvine’s Apes, Angels, and Victorians (1955), subtitled The Story of Darwin, Huxley, and Evolution, which opens with a dramatic rendering of the Huxley-Wilberforce debate. When Irvine’s book was reprinted in 1963, it even came with a preface by Julian Huxley, the grandson of Thomas Henry and a great evolutionary biologist himself (Fig. 4).

The legendary account of the Huxley-Wilberforce exchange has lived on in literary studies as well. In part that is due to Irvine, then a professor of English at ![]() Stanford. The greater cause, however, is undoubtedly the inclusion of Leonard Huxley’s account of the Huxley-Wilberforce exchange in the Norton Anthology of English Literature. Since its very first edition a half century ago, that venerable anthology has contained a section under the Victorian Age devoted to Evolution in which Leonard’s account has always appeared. In 1962 that was understandable. The centennial of the Origin of Species in 1959 had renewed interest in Darwin, and Irvine’s book had helped make the Oxford debate a modern touchstone of the Victorian period. By the time of the Norton’s sixth edition in 1993, however, or certainly by the seventh edition in 2000, the inclusion of Leonard Huxley’s version of the encounter had become deeply problematic given the proliferating number of revisionist studies of the event. The excerpt has always been accompanied by a note explaining that “[b]ecause no complete transcript of this celebrated debate was made at the time,” Leonard Huxley “had to reconstruct the scene by combining quotations from reports made by magazine writers and other witnesses” (Greenblatt et al. 1573). Yet this explanation is hardly adequate, implicitly treating Leonard’s account as a collation of reports from objective observers and persisting in treating the exchange as a “debate.” Worse, the headnote to the section on Evolution presents Wilberforce as the spokesman that day for the two main groups of Darwin’s opponents: “scientists who affirmed that his theory was unsound” and “religious leaders who attacked his theory because it seemed to contradict a literal interpretation of the Bible” (1560). This simplistic schema, which ignores the fact that many leading scientists were also religious leaders and treats Wilberforce erroneously as a biblical literalist, furthers misconceptions about both science and religion in the period, in particular implying that Darwin’s scientific critics objected to his theory solely on scientific grounds, while religious leaders objected out of a reactionary commitment to biblical literalism.[2]

Stanford. The greater cause, however, is undoubtedly the inclusion of Leonard Huxley’s account of the Huxley-Wilberforce exchange in the Norton Anthology of English Literature. Since its very first edition a half century ago, that venerable anthology has contained a section under the Victorian Age devoted to Evolution in which Leonard’s account has always appeared. In 1962 that was understandable. The centennial of the Origin of Species in 1959 had renewed interest in Darwin, and Irvine’s book had helped make the Oxford debate a modern touchstone of the Victorian period. By the time of the Norton’s sixth edition in 1993, however, or certainly by the seventh edition in 2000, the inclusion of Leonard Huxley’s version of the encounter had become deeply problematic given the proliferating number of revisionist studies of the event. The excerpt has always been accompanied by a note explaining that “[b]ecause no complete transcript of this celebrated debate was made at the time,” Leonard Huxley “had to reconstruct the scene by combining quotations from reports made by magazine writers and other witnesses” (Greenblatt et al. 1573). Yet this explanation is hardly adequate, implicitly treating Leonard’s account as a collation of reports from objective observers and persisting in treating the exchange as a “debate.” Worse, the headnote to the section on Evolution presents Wilberforce as the spokesman that day for the two main groups of Darwin’s opponents: “scientists who affirmed that his theory was unsound” and “religious leaders who attacked his theory because it seemed to contradict a literal interpretation of the Bible” (1560). This simplistic schema, which ignores the fact that many leading scientists were also religious leaders and treats Wilberforce erroneously as a biblical literalist, furthers misconceptions about both science and religion in the period, in particular implying that Darwin’s scientific critics objected to his theory solely on scientific grounds, while religious leaders objected out of a reactionary commitment to biblical literalism.[2]

Although the traditional account of the Huxley-Wilberforce encounter has long been discredited by historians, understanding the contexts in play that day, and how that traditional account acquired the aura of truth, has much to teach us about science, religion, and Victorian culture.

The British Association for the Advancement of Science was a relatively young organization in 1860, having been founded just thirty years before. Membership and participation were to be more meritocratic than Britain’s most prestigious and much older scientific body, the ![]() Royal Society of London (f. 1660), although gaining power and authority meant inclusion of sympathetic aristocrats, urban gentry, and wealthy manufacturers. To promote the pursuit of science throughout Britain, the Association’s annual meeting moved from city to city, and some of the proceedings were open to the public. The Association was dominated in its early decades, however, by a gentlemanly elite centered in London and Cambridge, many of them in holy orders (see Morrell and Thackray). For these men, mindful of the connections between scientific materialism and radical politics and atheism, particularly in

Royal Society of London (f. 1660), although gaining power and authority meant inclusion of sympathetic aristocrats, urban gentry, and wealthy manufacturers. To promote the pursuit of science throughout Britain, the Association’s annual meeting moved from city to city, and some of the proceedings were open to the public. The Association was dominated in its early decades, however, by a gentlemanly elite centered in London and Cambridge, many of them in holy orders (see Morrell and Thackray). For these men, mindful of the connections between scientific materialism and radical politics and atheism, particularly in ![]() France and among the medical community in London (see Desmond, Politics of Evolution), natural science should be pursued and defended as a buttress to Christianity, and thus to the moral and political order of society. This gentlemanly elite reserved to itself the right to speculate and theorize; those from the provinces or without connections to traditional institutional bulwarks like the ancient universities or the

France and among the medical community in London (see Desmond, Politics of Evolution), natural science should be pursued and defended as a buttress to Christianity, and thus to the moral and political order of society. This gentlemanly elite reserved to itself the right to speculate and theorize; those from the provinces or without connections to traditional institutional bulwarks like the ancient universities or the ![]() Royal College of Surgeons were expected to confine themselves to such empirical enterprises as field observations and data collection, preferably as part of a larger project endorsed by the elites.

Royal College of Surgeons were expected to confine themselves to such empirical enterprises as field observations and data collection, preferably as part of a larger project endorsed by the elites.

Thus it was that, fifteen years earlier, at the 1845 BAAS meeting at Cambridge, the Association’s leading lights had attacked another work of evolutionary speculation, the recently-published Vestiges of the Natural History of Creation (Secord 406-10). Vestiges had appeared anonymously and become a cultural and scientific sensation; the work of ![]() Edinburgh publisher Robert Chambers (Fig. 5), it synthesized evidence from across the natural sciences to present a grand cosmic narrative of change and development. Such evolutionary ideas were dangerous in the eyes of the British scientific elite, particularly in the economic depression and social turmoil of the 1840s. Many—including the young Huxley—also saw Vestiges as marred by numerous scientific errors. For Darwin, who had then just completed a draft of his own theory, the response to Vestiges provided a cautionary example of what might lie in store for him. Over the ensuing years, he was determined to distinguish his work from Vestiges and avoid the latter’s mistakes and provocations. As a well-respected member of the scientific elite himself, Darwin had reason to hope for a less vituperative reception than the anonymous author of Vestiges had received, but he knew well that his ideas would nonetheless unleash similar criticisms.

Edinburgh publisher Robert Chambers (Fig. 5), it synthesized evidence from across the natural sciences to present a grand cosmic narrative of change and development. Such evolutionary ideas were dangerous in the eyes of the British scientific elite, particularly in the economic depression and social turmoil of the 1840s. Many—including the young Huxley—also saw Vestiges as marred by numerous scientific errors. For Darwin, who had then just completed a draft of his own theory, the response to Vestiges provided a cautionary example of what might lie in store for him. Over the ensuing years, he was determined to distinguish his work from Vestiges and avoid the latter’s mistakes and provocations. As a well-respected member of the scientific elite himself, Darwin had reason to hope for a less vituperative reception than the anonymous author of Vestiges had received, but he knew well that his ideas would nonetheless unleash similar criticisms.

The Oxford BAAS meeting in 1860 offered the first opportunity for practitioners of science, gathered together, to discuss and debate Darwin’s book. In that light, one of the most striking features of the Association’s program was the comparative absence of Darwin’s name. Darwin himself was not present. Never eager to put himself in the direct path of controversy, he was probably relieved to be able to invoke the illness of his daughter and his own poor health as reasons for staying away. The astronomer Lord Wrottesley, in his presidential address, made no mention of Darwin’s book in his survey of the previous year’s major achievements in science (Report lv-lxxv). No sessions were devoted to Darwin’s theory, and only two papers referred to Darwin by name in their titles (Report vii-xvi). The Association seemed determined to avoid or at least limit formal controversy over evolution. Darwin’s opponents, however, seemed eager to take advantage of even meager opportunities to go on the attack.

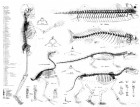

Figure 7: Owen’s archetypal vertebrate skeleton (upper right) and those of fish, reptiles, birds, mammals, and humans

The first paper to afford such an opportunity was Charles Daubeny’s “Remarks on the Final Causes of the Sexuality of Plants, with particular reference to Mr. Darwin’s Work ‘On the Origin of Species by Natural Selection,’” delivered on Thursday, 28 June, to Section D, Botany and Zoology, including Physiology. Daubeny, Professor of Botany at Oxford, argued that natural selection might be responsible for the development of sexual organs in plants and offered a cautious endorsement of Darwin’s theory, though he “wished not to be considered as advocating it to the extent to which the author seems disposed to carry it” (“Science—British Association” 26). Huxley was present, as was Richard Owen (Fig. 6), Britain’s leading comparative anatomist and the superintendant of the natural history collections at the ![]() British Museum. Owen’s view of the history of life—that organisms had not evolved but rather unfolded through time according to the Creator’s plan, with species varying from archetypal forms present in the divine mind—was the dominant one in the 1840s and 50s. (See Fig. 7.) Huxley, a rising star but over twenty years Owen’s junior, had come increasingly to regard Owen’s archetypal anatomy as inadequate and Owen himself as someone obsessed with power and privilege.[3] The two men had been arguing in public for some time over the brains of apes versus those of humans, a charged issue with obvious implications for the question of human descent. In the seven months following the publication of the Origin, Huxley had already emerged as Darwin’s main defender, writing three major, favorable reviews of it and supporting it in a lecture at

British Museum. Owen’s view of the history of life—that organisms had not evolved but rather unfolded through time according to the Creator’s plan, with species varying from archetypal forms present in the divine mind—was the dominant one in the 1840s and 50s. (See Fig. 7.) Huxley, a rising star but over twenty years Owen’s junior, had come increasingly to regard Owen’s archetypal anatomy as inadequate and Owen himself as someone obsessed with power and privilege.[3] The two men had been arguing in public for some time over the brains of apes versus those of humans, a charged issue with obvious implications for the question of human descent. In the seven months following the publication of the Origin, Huxley had already emerged as Darwin’s main defender, writing three major, favorable reviews of it and supporting it in a lecture at ![]() London’s Royal Institution. For his part, Owen had published a scathing anonymous review in the Edinburgh and was rumored to be conspiring with Wilberforce, with whom he stayed while in Oxford, to attack Darwin’s theory. A conflict between Owen and Huxley seemed inevitable. When called upon to respond to Daubeny’s paper, however, Huxley demurred, asserting that a public venue was not the place for a dispassionate discussion of Darwin’s theory. Owen seized the opportunity, aiming his remarks at the very public that Huxley disdained. The human brain, Owen explained, was vastly different from the brain of apes. Humans, he reassured the audience, had not descended from monkeys. This was too much for Huxley. Obtaining the floor, he asserted his total opposition to Owen’s position. The anatomical similarities between humans and apes were substantial and significant, he declared. Human dignity and privilege would not be imperiled by such a connection, and humans would remain morally responsible for their actions. Even the clergy “had nothing to fear,” Huxley claimed, “should it be shown that apes were their ancestors” (“Literature and Art”).

London’s Royal Institution. For his part, Owen had published a scathing anonymous review in the Edinburgh and was rumored to be conspiring with Wilberforce, with whom he stayed while in Oxford, to attack Darwin’s theory. A conflict between Owen and Huxley seemed inevitable. When called upon to respond to Daubeny’s paper, however, Huxley demurred, asserting that a public venue was not the place for a dispassionate discussion of Darwin’s theory. Owen seized the opportunity, aiming his remarks at the very public that Huxley disdained. The human brain, Owen explained, was vastly different from the brain of apes. Humans, he reassured the audience, had not descended from monkeys. This was too much for Huxley. Obtaining the floor, he asserted his total opposition to Owen’s position. The anatomical similarities between humans and apes were substantial and significant, he declared. Human dignity and privilege would not be imperiled by such a connection, and humans would remain morally responsible for their actions. Even the clergy “had nothing to fear,” Huxley claimed, “should it be shown that apes were their ancestors” (“Literature and Art”).

This confrontation set the stage for Huxley’s exchange with Wilberforce two days later. John William Draper (1811-1882; see Fig. 8) was scheduled to speak to Section D on “The Intellectual Development of Europe, considered with reference to the views of Mr. Darwin and others, that the Progression of Organisms is determined by Law.” Draper had been born and educated in England but moved as a young man to America, building a distinguished career in science and medicine as Professor of Chemistry and Physiology at what was then known as the University of the ![]() City of New York. By 1860, he had already declared his support for the transmutation of species in his successful 1856 textbook, Human Physiology, Statical and Dynamical. Arguing that “[s]ocial advancement is as completely under the control of natural law as is bodily growth” (History of the Intellectual Development iii), Draper previewed for the BAAS his forthcoming book, an analysis of European civilization on physiological principles. It had little or nothing to do with Darwin’s work—the attempt to discern laws of social change and progress was more the province of Auguste Comte, Herbert Spencer, and Henry Thomas Buckle, and Hooker disdainfully described Draper’s address to Darwin as “all a pie of Herbt Spenser [sic] and Buckle without the seasoning of either” (Hooker to Darwin, 2 July 1860; Darwin Correspondence Database). Nonetheless, Draper’s talk attracted such a large audience—probably 400 to 700—that the session had to be moved to a larger venue to accommodate the throng of Association members, Oxford dons, rowdy undergraduates, and a smattering of female guests.

City of New York. By 1860, he had already declared his support for the transmutation of species in his successful 1856 textbook, Human Physiology, Statical and Dynamical. Arguing that “[s]ocial advancement is as completely under the control of natural law as is bodily growth” (History of the Intellectual Development iii), Draper previewed for the BAAS his forthcoming book, an analysis of European civilization on physiological principles. It had little or nothing to do with Darwin’s work—the attempt to discern laws of social change and progress was more the province of Auguste Comte, Herbert Spencer, and Henry Thomas Buckle, and Hooker disdainfully described Draper’s address to Darwin as “all a pie of Herbt Spenser [sic] and Buckle without the seasoning of either” (Hooker to Darwin, 2 July 1860; Darwin Correspondence Database). Nonetheless, Draper’s talk attracted such a large audience—probably 400 to 700—that the session had to be moved to a larger venue to accommodate the throng of Association members, Oxford dons, rowdy undergraduates, and a smattering of female guests.

Draper’s ideas and eloquence, however, were not what drew the crowd, but the rumor that Wilberforce was going to use the occasion to attack Darwin’s theory. Huxley had heard of it and again vowed to avoid a public dispute: Soapy Sam’s oratorical skills deployed in such a venue would not conduce to a fair hearing for evolution. Besides, he was tired and wanted to return to his family. It was Vestiges author Robert Chambers, ironically, who induced Huxley to stay by accusing him of deserting the evolutionary cause. Hooker, too, had heard of Wilberforce’s plans. He only decided to attend at the last minute, he told Darwin, and merely out of boredom and curiosity at what the Bishop would say. Hooker clearly felt no obligation to attend expressly to defend Darwin’s book, and he jokingly complained at “being woke out of reveries to become referee on Natural Selection” (Hooker to Darwin, 2 July 1860; Darwin Correspondence Database).

Draper’s address was followed by a number of comments and speeches from the floor. The specifics of Draper’s argument were largely forgotten in favor of assessments of Darwin’s theory. The meeting’s chairman, the venerable Cambridge botanist John Stevens Henslow, mentor to Darwin during the latter’s undergraduate years and the father-in-law of Hooker, sought to keep the discussion on civil and scientific grounds. When Wilberforce’s turn came, he seized it, speaking for thirty minutes. His arguments reflected those he had recently penned for his anonymous review of the Origin soon to appear in the Quarterly. Darwin’s theory was speculative rather than a valid induction from established facts and lacked an observational or experimental basis. The analogy between natural selection and human breeding of domesticated animals on which Darwin relied so heavily in fact told against him: domesticated breeds reverted to type when no longer under human control and crosses between species invariably resulted in sterile hybrids. The line between humans and animals was distinct and permanent. Yes, Wilberforce asserted that the dignity of humans and our special status as creation and concern of an omnipotent and benevolent deity was imperiled by an animal ancestry, but that was not the focus of his remarks. (When Darwin read Wilberforce’s anonymous review a few weeks later, he declared it “uncommonly clever”; it “picks out with skill all the most conjectural parts, & brings forward well all difficulties,” he wrote to Hooker [Darwin to Hooker, 20? July 1860; Darwin Correspondence Database].) Human dignity was the basis, however, for Wilberforce’s closing quip. Playing off Huxley’s remark two days earlier that human privilege and moral responsibility would not be endangered by sharing a genealogy with apes, Wilberforce turned to Huxley, who was seated on the platform with him, and asked him the question about the precise location of the apes in the Huxley family tree.

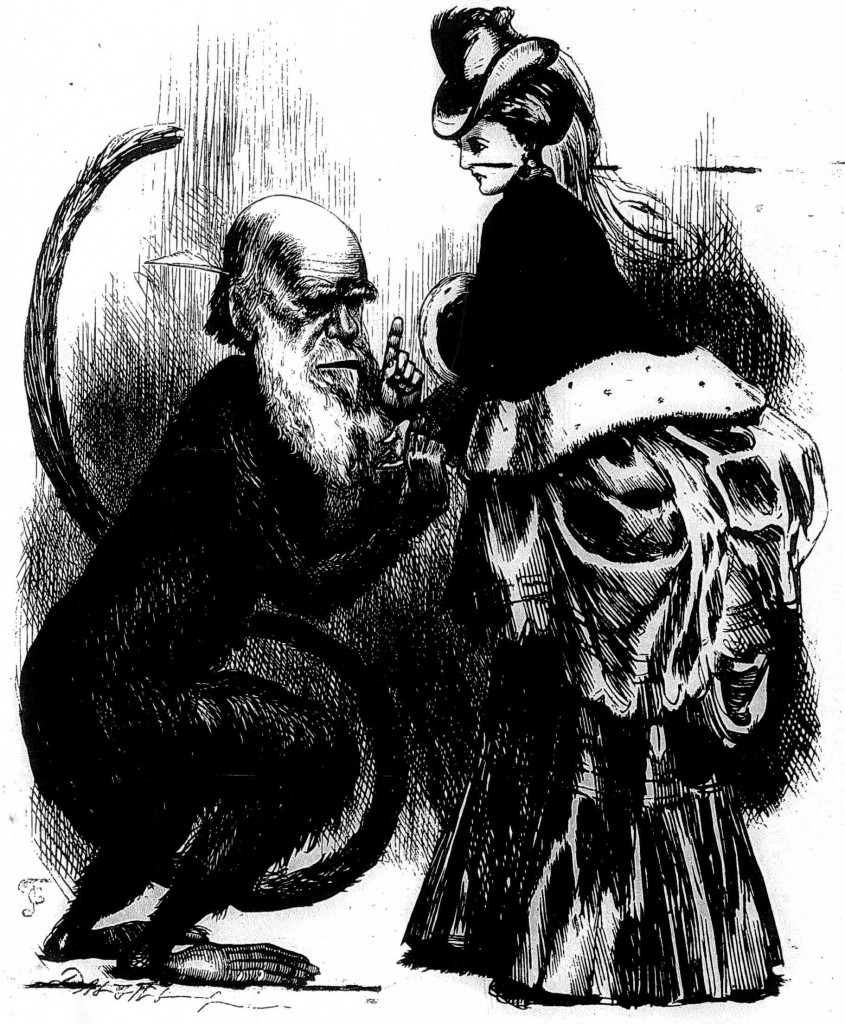

The exact wording of Wilberforce’s question is uncertain—observers recalled many different variations. The London Press was the only newspaper to report a specific version, and it had the Bishop asking Huxley “whether he would prefer a monkey for his grandfather or his grandmother?” (“Literature and Art”). This corresponds with Huxley’s characterization of the Bishop’s question two months after the event as concerning “my personal predilections in the matter of ancestry” (Huxley to Frederick Dyster, 9 Sept. 1860; qtd. in James 179). Whatever its precise form, Wilberforce’s query drew laughter, though many observers felt it was in bad taste or even ungentlemanly. A serious scientific discussion should not be lowered by what appeared to be a personal jibe. A leading figure of the church should not cast even joking aspersions on another man’s forebears. By raising the possibility of a monkey in Huxley’s maternal line, Wilberforce also evoked the culturally disturbing notion of sexual congress between humans and apes, an image that, as Gowan Dawson has shown (55-74), was often deployed to discredit evolution. (See Fig. 9.)

Figure 9: One of the many contemporary cartoons and caricatures casting Darwin as a monkey or an ape. Note the phallic and serpentine quality of Darwin’s tail.

Whether or not he felt personally insulted, Huxley took advantage of the opening. He said he had heard nothing new in the Bishop’s speech, except for the question about his ancestry, and though that was a topic he would not have introduced, he would reply. The precise wording of his retort is also uncertain, but the version Huxley provided two months later is probably fairly accurate: “If then, said I, the question is put to me would I rather have a miserable ape for a grandfather or a man highly endowed by nature and possessing great means & influence & yet who employs those faculties & that influence for the mere purpose of introducing ridicule into a grave scientific discussion—I unhesitatingly affirm my preference for the ape” (Huxley to Dyster, 9 Sept. 1860; qtd. in James 179). Huxley subtly drew attention to the Bishop’s behavior and his lack of scientific credentials. He rhetorically chastised Wilberforce for deploying rhetoric, as if this were a political debate in the ![]() Oxford Union or the House of Lords (to both of which Wilberforce was prominently connected) rather than “a grave scientific discussion.” Huxley’s reference to the Bishop’s “introducing ridicule” into the discussion probably reflects more than just Wilberforce’s jibe at Huxley. Hooker told Darwin that Wilberforce had “ridiculed you badly and Huxley savagely” (Hooker to Darwin, 2 July 1860; Darwin Correspondence Database), and, even allowing for partisan hyperbole, both the comments of other observers and the content of Wilberforce’s review in the Quarterly suggest his humor in this case had a hard and even a personal edge. Significantly, both at the time and many years later, Huxley took pains to deny the widely circulated claim that he had said he would rather be an ape than a bishop or had in any way insulted Wilberforce in his reply.[4]

Oxford Union or the House of Lords (to both of which Wilberforce was prominently connected) rather than “a grave scientific discussion.” Huxley’s reference to the Bishop’s “introducing ridicule” into the discussion probably reflects more than just Wilberforce’s jibe at Huxley. Hooker told Darwin that Wilberforce had “ridiculed you badly and Huxley savagely” (Hooker to Darwin, 2 July 1860; Darwin Correspondence Database), and, even allowing for partisan hyperbole, both the comments of other observers and the content of Wilberforce’s review in the Quarterly suggest his humor in this case had a hard and even a personal edge. Significantly, both at the time and many years later, Huxley took pains to deny the widely circulated claim that he had said he would rather be an ape than a bishop or had in any way insulted Wilberforce in his reply.[4]

Huxley’s rejoinder drew cheers and laughter of its own, but his was hardly the last word, and it certainly didn’t win the day for Darwin’s advocates. Several speakers followed Huxley, including a number who rejected Darwin’s theory. Even Hooker felt that, although Huxley had “answered admirably & turned the tables,” he had not attacked Wilberforce’s weak points “nor put the matter in a form or way that carried the audience” (Hooker to Darwin, 2 July 1860; Darwin Correspondence Database). Hooker (Fig. 10) himself spoke last, and it was he who offered both the most extensive defense of Darwin’s theory and the most direct attack on Wilberforce. According to both his own account and that in the Athenaeum, he challenged whether the Bishop had read and understood Darwin’s book and explained the ways in which natural selection was confirmed by and made sense of botany (Hooker to Darwin, 2 July 1860; Darwin Correspondence Database; “Science—British Association” 65). Although generally omitted from the traditional account, Hooker’s speech was a major element of the day, and some of those present (including Hooker, but not just him) thought it the most important in substance. Most observers, however, would remember the exchange between Huxley and Wilberforce.

As to who “won” that exchange, opinion at the time was divided. Some thought Huxley, others the Bishop, still others declared it a draw. Huxley and Hooker were confident their side had prevailed, but Wilberforce declared to a correspondent that he had “thoroughly beat” Huxley (Wilberforce to Charles Anderson, 3 July 1860; qtd. in Altholz 315). For Darwin’s supporters—and through them, Darwin himself—the exchange was momentous and did mark a turning point in the fortunes of Darwinism within the scientific community and in science’s struggle for independence from religious authority. Darwin regarded Huxley and Hooker’s willingness to “fight publicly” as vital to the ultimate acceptance of his ideas and within weeks was declaring “it seems that Oxford did the subject great good” (Darwin to Hooker, 2 July 1860; Darwin to Huxley, 20 July 1860; Darwin Correspondence Database). It is thus not surprising that, a generation later, Francis Darwin and Leonard Huxley, drawing on the correspondence of their fathers and the recollections of their fathers’ friends and allies, told the story in that way. The encounter, Leonard Huxley admitted, could not be described as “an immediate and complete triumph for evolutionary doctrine,” but its importance lay “in the open resistance that was made to authority, at a moment when even a drawn battle was hardly less effectual than acknowledged victory. Instead of being crushed under ridicule, the new theories secured a hearing” (Life and Letters of Thomas Henry Huxley 1: 189).

Huxley’s phrasing is telling. He speaks of “evolutionary doctrine” rather than “natural selection,” because even at the end of the century the latter was still not widely accepted as the chief mechanism of evolutionary change (that would not occur for several more decades) and T. H. Huxley himself had never fully embraced it. And the “authority” that was resisted and had sought to “crush” evolutionary doctrine with “ridicule” points, of course, to the clerical authority represented by Wilberforce. That simplistic notion of a clash or battle between science and religion, as revisionist accounts have frequently noted, was a reflection of the late-century rhetoric of scientific naturalists like Huxley, those advocates of science who wished to replace the authority of religion with the authority of science on a range of issues dealing with the natural and social worlds. This “conflict” model was vividly captured in the titles of two widely read books of the era, History of the Conflict of Science and Religion (1874), by none other than John William Draper, whose paper had sparked the exchange between Huxley and Wilberforce, and Andrew Dickson White’s A History of the Warfare of Science with Theology in Christendom (1896), the latter describing Huxley’s riposte as a “shot” that “reverberated through England” (1: 71). Such martial language and imagery, as we have seen, were part of Huxley’s own rhetorical stock in trade, both privately and publicly, in advancing the cause of Darwinism and scientific naturalism more generally.

At the time of the Oxford debate, the relationship between science and religion was being shaped in more subtle ways. Chief among these was professionalization within science.[5] The Oxbridge dons and country parsons who had dominated the pursuit of the natural sciences in Britain in the first half of the nineteenth century were giving way to men like Huxley, men often from the middle and lower-middle classes and from outside of the Anglican communion, men who had been trained in science and pursued it as a vocation rather than an avocation. Such men often rejected or had little use for the rationale that the study of nature reinforced the understanding of nature’s god. They bristled at the notion that there were aspects of nature they should not investigate, or theories they should not promote. For Huxley, the morality of the scientist lay in resisting appeals to authority and affirming as true only that for which he can provide empirical evidence. A few years after the Oxford meeting, he would coin the term “Agnostic” to describe this position. Wilberforce in Huxley’s eyes epitomized both the kind of person and the mode of thinking Huxley wished to purge from science: a privileged, Oxford-educated figure of authority in the Anglican church, holding forth at the BAAS—despite not working as a scientist—in an effort to quash discussion of the major scientific controversy of the day.

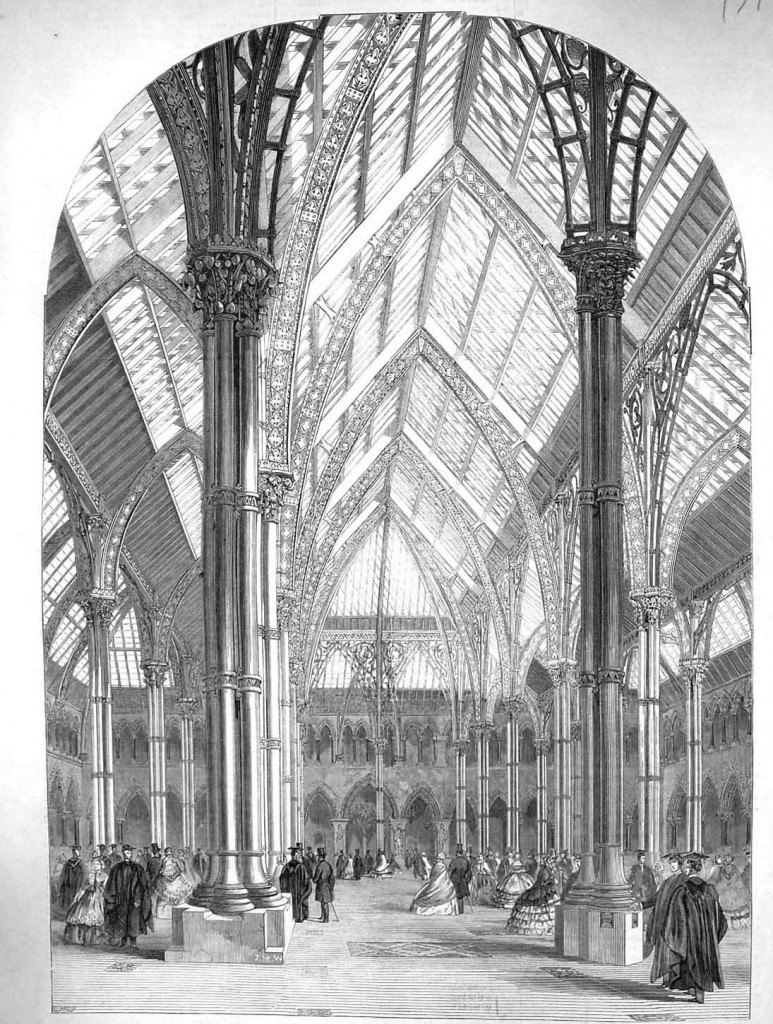

The building in which the exchange between Huxley and Wilberforce took place was, despite its newness, itself emblematic of the traditional natural theology that Huxley hoped to wipe away. Oxford’s new Natural History Museum would not open for several more months; the large room to which Section D was moved for Draper’s paper was not yet finished. That Oxford had such a museum at all was a testament to the efforts of those within and without the University who wanted the natural sciences to have a greater presence there—efforts led by Henry Acland, the Regius Professor of Medicine; cheered on and in many ways inspired by the work of Acland’s friend, the art critic and Oxford graduate John Ruskin; and strongly supported by Wilberforce. The neo-Gothic building was designed as a cathedral of nature, complete with the angel of life carved over the door, reflective of the belief that the study of nature was the study of the works of god (Yanni 62-90). (See Fig. 11.) As the museum opened, however, that conceptualization of science was increasingly being challenged or simply ignored, and a younger generation of scientists, even those without Huxley’s militancy, was operating with different assumptions.

Figure 11: The Central Court and Arcades of the ![]() Oxford University Museum

Oxford University Museum

Neither, of course, was religion, nor even Anglicanism, stable and monolithic in this period. Indeed, the Anglican Church was experiencing intense internal divisions. Its liberal members embraced science and the new historical approach to Biblical scholarship emanating from ![]() Germany, seeking a modern Anglicanism in step with new knowledge. Just three months prior to the BAAS meeting, seven liberal Anglicans—six of them well-known clergymen, four with positions at Oxford—had published Essays and Reviews, a collection embracing this new Biblical scholarship, and in which Oxford’s Savilian Professor of Geometry Baden Powell had praised Darwin’s “masterly volume” and predicted “an entire revolution of opinion in favour of the grand principle of the self-evolving powers of nature” (139). The public furor provoked by Essays and Reviews was more intense in the early 1860s than that provoked by the Origin, immensely so within the Anglican Church. Both the Church’s evangelical and Anglo-Catholic wings were deeply skeptical of or hostile to such accommodations with modern thought. As the Bishop of Oxford, Wilberforce had to navigate among these often-competing interests within the Church. The son of a famous evangelical abolitionist, Wilberforce nonetheless frequently aligned himself with the High Church party, although he did not embrace the Anglo-Catholic movement led by Oxford divines John Henry Newman, Edmund Pusey, and John Keble in the 1830s and 40s. While an enthusiastic supporter of science undergirded by natural theology, Wilberforce saw evolutionary ideas as fundamentally at odds with Christianity’s view of humanity and its relationship with the divine. The Origin of Species and Essays and Reviews were thus of a piece to Wilberforce, mutually reinforcing threats to the faith. Less than a year after attacking the Origin in the Quarterly Review, Wilberforce heaped similarly heated abuse on Essays and Reviews in the same venue. His opposition to Darwinism thus must be seen in that context, as part of a reaction to a threat he saw coming fundamentally from within the Anglican church, not outside it. This also explains why both Huxley and Hooker would speak of being widely congratulated by many Oxford clergy for standing up publicly to their bishop (Huxley to Dyster, 9 Sept. 1860; qtd. in James 181; Hooker to Darwin, 2 July 1860; Darwin Correspondence Database).

Germany, seeking a modern Anglicanism in step with new knowledge. Just three months prior to the BAAS meeting, seven liberal Anglicans—six of them well-known clergymen, four with positions at Oxford—had published Essays and Reviews, a collection embracing this new Biblical scholarship, and in which Oxford’s Savilian Professor of Geometry Baden Powell had praised Darwin’s “masterly volume” and predicted “an entire revolution of opinion in favour of the grand principle of the self-evolving powers of nature” (139). The public furor provoked by Essays and Reviews was more intense in the early 1860s than that provoked by the Origin, immensely so within the Anglican Church. Both the Church’s evangelical and Anglo-Catholic wings were deeply skeptical of or hostile to such accommodations with modern thought. As the Bishop of Oxford, Wilberforce had to navigate among these often-competing interests within the Church. The son of a famous evangelical abolitionist, Wilberforce nonetheless frequently aligned himself with the High Church party, although he did not embrace the Anglo-Catholic movement led by Oxford divines John Henry Newman, Edmund Pusey, and John Keble in the 1830s and 40s. While an enthusiastic supporter of science undergirded by natural theology, Wilberforce saw evolutionary ideas as fundamentally at odds with Christianity’s view of humanity and its relationship with the divine. The Origin of Species and Essays and Reviews were thus of a piece to Wilberforce, mutually reinforcing threats to the faith. Less than a year after attacking the Origin in the Quarterly Review, Wilberforce heaped similarly heated abuse on Essays and Reviews in the same venue. His opposition to Darwinism thus must be seen in that context, as part of a reaction to a threat he saw coming fundamentally from within the Anglican church, not outside it. This also explains why both Huxley and Hooker would speak of being widely congratulated by many Oxford clergy for standing up publicly to their bishop (Huxley to Dyster, 9 Sept. 1860; qtd. in James 181; Hooker to Darwin, 2 July 1860; Darwin Correspondence Database).

Leonard Huxley also claimed that through the confrontation with Wilberforce his father “first made himself known in popular estimation as a dangerous adversary in debate—a personal force in the world of science” (Life and Letters of Thomas Henry Huxley 1: 179). The experience certainly was exhilarating for Huxley, and it helped him appreciate the potential benefits of public controversy, but it was hardly his first foray into such a venue. It arguably did cement his reputation as a powerful force within the scientific community, although it could not have done so “in public estimation” given the limited press coverage of the event. It would also be another decade, as Bernard Lightman has demonstrated (353-97), before Huxley would truly begin to popularize science aggressively—prompted in particular by the recognition that most people were getting their Darwin not from Darwin’s books but in bestselling works of popular science framed by natural theology. Evolution was being more widely accepted by the public but accepted, Huxley realized to his horror, in the old from-nature-to-nature’s-god fashion, in books by clergymen, pious women, and other non-scientists. Much of the rest of Huxley’s life was thus devoted to education reform, science teaching, and writing and lecturing to popular audiences. If Oxford had marked a battle, it was not a ![]() Waterloo.

Waterloo.

The “debate” between Huxley and Wilberforce thus never happened, at least not in the fashion that what was once the received account would have it. And that received account was itself codified at a time when Darwin was widely hailed and evolution widely accepted, but natural selection was still not embraced and scientific naturalism was still fighting for cultural authority. Yet from that exercise in myth-making, and the encounter that provided the basis for it, we can glean a richer and more complex sense of Darwinism’s reception and of the relationship between religion and science in the Victorian period.

published February 2013

HOW TO CITE THIS BRANCH ENTRY (MLA format)

Smith, Jonathan. “The Huxley-Wilberforce ‘Debate’ on Evolution, 30 June 1860.” BRANCH: Britain, Representation and Nineteenth-Century History. Ed. Dino Franco Felluga. Extension of Romanticism and Victorianism on the Net. Web. [Here, add your last date of access to BRANCH].

WORKS CITED

Altholz, Josef L. “The Huxley-Wilberforce Debate Revisited.” Journal of the History of Medicine and Allied Sciences 35 (1980): 313-16. Print.

Brooke, John Hedley. “The Wilberforce-Huxley Debate: Why Did it Happen?” Science and Christian Belief 13 (2001): 127-141. Print.

Browne, Janet. “The Charles Darwin-Joseph Hooker Correspondence: An Analysis of Manuscript Resources and their Use in Biography.” Journal of the Society for the Bibliography of Natural History 8 (1978): 351-66. Print.

Caudill, Edward. Darwinian Myths: The Legends and Misuses of a Theory. Knoxville: U of Tennessee P, 1997. Print.

Darwin Correspondence Database. University of Cambridge. Web. 11 Sept. 2012.

Darwin, Francis. The Life and Letters of Charles Darwin. 3 vols. London: Murray, 1887. The Complete Work of Charles Darwin Online. Web. 8 Sept. 2012.

Dawson, Gowan. Darwin, Literature, and Victorian Respectability. Cambridge: Cambridge UP, 2007. Print.

Desmond, Adrian. Archetypes and Ancestors: Palaeontology in Victorian London, 1850-1875. Chicago: U of Chicago P, 1982. Print.

—. Huxley: The Devil’s Disciple. London: Michael Joseph, 1994. Print.

—. The Politics of Evolution: Morphology, Medicine, and Reform in Radical London. Chicago: U of Chicago P, 1989. Print.

Draper, John William. History of the Conflict of Science and Religion. New York: Appleton, 1874. HathiTrust Digital Library. Web. 14 Sept. 2012.

—. A History of the Intellectual Development of Europe. New York: Harper, 1863. HathiTrust Digital Library. Web. 14 Sept. 2012.

—. Human Physiology, Statical and Dynamical. New York: Harper, 1856. HathiTrust Digital Library. Web. 14 Sept. 2012.

Essays and Reviews. London: Parker, 1860. HathiTrust Digital Library. Web. 19 Sept. 2012.

Gilley, Sheridan. “The Huxley-Wilberforce Debate: A Reconsideration.” Religion and Humanism. Ed. Keith Robbins. Oxford: Blackwell, 1981. 325-40. Print.

Gould, Stephan Jay. “Knight Takes Bishop?” Natural History May 1986: 18+. Print. Rpt. in Bully for Brontosaurus: Reflections in Natural History. New York: Norton, 1991. 385-401. Print.

Greenblatt, Stephen, et al., eds. The Norton Anthology of English Literature. 9th ed. Vol. 2. New York: Norton, 2012. Print.

Hesketh, Ian. Of Apes and Ancestors: Evolution, Christianity, and the Oxford Debate. Toronto: U of Toronto P, 2009. Print.

Huxley, Leonard. Life and Letters of Joseph Dalton Hooker. 2 vols. London: Murray, 1918. HathiTrust Digital Library. Web. 16 Aug. 2012.

—. Life and Letters of Thomas Henry Huxley. 2 vols. London: Macmillan, 1900. HathiTrust Digital Library. Web. 16 Aug. 2012.

Irvine, William. Apes, Angels, and Victorians: The Story of Darwin, Huxley, and Evolution. New York: McGraw-Hill, 1955. Print.

James, Frank A. J. L. “An ‘Open Clash between Science and the Church’?: Wilberforce, Huxley and Hooker on Darwin at the British Association, Oxford, 1860.” Science and Beliefs: From Natural Philosophy to Natural Science, 1700-1900. Ed. David M. Knight and Matthew D. Eddy. Aldershot: Ashgate, 2005. 171-93. Print.

Jensen, J. Vernon. “Return to the Huxley-Wilberforce Debate.” British Journal for the History of Science 21 (1988): 161-79. JSTOR. Web. 30 Aug. 2012.

Lightman, Bernard. Victorian Popularizers of Science: Designing Nature for New Audiences. Chicago: U of Chicago P, 2007. Print.

“Literature and Art.” The Press [London] 7 July 1860: 656. Print.

Livingstone, David N. “Myth 17. That Huxley Defeated Wilberforce in Their Debate over Evolution and Religion.” Galileo Goes to Jail and Other Myths About Science and Religion. Ed. Ronald L. Numbers. Cambridge, MA: Harvard UP, 2009. 152-60. Print.

Lucas, J. R. “Wilberforce and Huxley: A Legendary Encounter.” The Historical Journal 22 (1979): 313-30. JSTOR. Web. 30 Aug. 2012.

Moore, James R. The Post-Darwinian Controversies. Cambridge: Cambridge UP, 1979. Print.

Morrell, Jack, and Arnold Thackray. Gentlemen of Science: Early Years of the British Association for the Advancement of Science. Oxford: Clarendon, 1981. Print.

[Owen, Richard.] “Darwin on the Origin of Species.” Edinburgh Review 111 (1860): 487-532. Periodicals Archive Online. Web. 12 Sept. 2012.

Report of the Thirtieth Meeting of the British Association for the Advancement of Science. London: Murray, 1861. Biodiversity Heritage Library. Web. 31 Aug. 2012.

Rupke, Nicolaas. Richard Owen: Biology without Darwin. Chicago: U of Chicago P, 2009. Print.

“Science—British Association.” The Athenaeum. 7 July and 14 July 1860: 18-32; 59-69. Print.

Secord, James A. Victorian Sensation: The Extraordinary Publication, Reception, and Secret Authorship of Vestiges of the Natural History of Creation. Chicago: U of Chicago P, 2000. Print.

Shapin, Steven. The Scientific Revolution. Chicago: U of Chicago P, 1996. Print.

Turner, Frank M. Contesting Cultural Authority: Essays in Victorian Intellectual Life. Cambridge: Cambridge UP, 1993. Print.

White, Andrew Dickson. A History of the Warfare of Science with Theology in Christendom. 2 vols. New York: Appleton, 1896. HathiTrust Digital Library. Web. 14 Sept. 2012.

Wilberforce, Reginald G. Life of the Right Reverend Samuel Wilberforce, D.D. Vol. 2. London: Murray, 1881. HathiTrust Digital Library. Web. 16 Aug. 2012.

—. Life of Samuel Wilberforce. London: Kegan Paul, 1888. HathiTrust Digital Library. Web. 16 Aug. 2012.

[Wilberforce, Samuel.] “Darwin’s Origin of Species.” Quarterly Review 108 (1860): 225-64. HathiTrust Digital Library. Web. 14 Sept. 2012.

Yanni, Carla. Nature’s Museums: Victorian Science and the Architecture of Display. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins UP, 1999. Print.

ENDNOTES

[1] I am adapting the opening sentence of Shapin.

[2] Revisionist accounts include those of Altholz, Brooke, Browne, Caudill 27-45, Gilley, Gould, James, Jensen, Livingstone, Lucas, Moore 60-2, and most recently and fully, Hesketh.

[3] Also problematic, for similar reasons, is the inclusion in the Norton Anthology’s Evolution section, since the first edition, of an excerpt from Edmund Gosse’s Father and Son (1907). The limited changes to the Evolution section (an excerpt on Darwin’s method of argument from John Tyndall’s 1874 Belfast Address was dropped from the fifth edition in 1986, and an excerpt from the Origin of Species itself was finally added in the seventh edition in 2000), despite a flood of scholarship on Darwin, evolution, and science and religion in the nineteenth century over the last fifty years, stands in sharp contrast to the changes to the Industrialism section (also present since the first edition) and to the introduction and often revision of newer sections.

[4] For accounts of the relationship between Owen and Huxley, see Rupke and Desmond, Archetypes and Ancestors and Huxley.

[5] Huxley’s 9 Sept. 1860 letter to Dyster (qtd. in Jensen 168) shows this to be true at the time. More than twenty years later, Huxley objected to Reginald Wilberforce’s use of that version of the retort in the initial Life of his father (451), inducing Wilberforce to change it to something closer to Huxley’s version in his revised edition of 1888 (248).

[6] On the role of professionalization in the relationship between religion and science and science’s struggle to gain cultural authority in the Victorian period, see Turner.